Abstract

Objective:

The Hotel Study was initiated in Vancouver’s Downtown East Side (DTES) neighborhood to investigate multimorbidity in homeless or marginally housed people. We evaluated the clinical effectiveness of existing, illness-specific treatment strategies and assessed the effectiveness of health care delivery for multimorbid illnesses.

Method:

For context, we mapped the housing locations of patients presenting for 552,062 visits to the catchment hospital emergency department (2005-2013). Aggregate data on 22,519 apprehensions of mentally ill people were provided by the Vancouver Police Department (2009-2015). The primary strategy was a longitudinal cohort study of 375 people living in the DTES (2008-2015). We analysed mortality and evaluated the clinical and health service delivery effectiveness for infection with human immunodeficiency virus or hepatitis C virus, opioid dependence, and psychosis.

Results:

Mapping confirmed the association between poverty and greater number of emergency visits related to substance use and mental illness. The annual change in police apprehensions did not differ between the DTES and other policing districts. During 1581 person-years of cohort observation, the standardized mortality ratio was 8.43 (95% confidence interval, 6.19 to 11.50). Physician visits were common (84.3% of participants over 6 months). Clinical treatment effectiveness was highest for HIV/AIDS, intermediate for opioid dependence, and lowest for psychosis. Health service delivery mechanisms provided examples of poor access, poor treatment adherence, and little effect on multimorbid illnesses.

Conclusions:

Clinical effectiveness was variable, and illness-specific service delivery appeared to have little effect on multimorbidity. New models of care may need to be implemented.

Keywords: psychosis, heroin, HIV, HCV, police, multimorbidity, mortality

Abstract

Objectif:

L’étude Hotel a débuté dans le quartier Downtown East Side (DTES) de Vancouver pour mener une recherche sur la multi-morbidité chez les personnes sans abri ou ayant un logement précaire. Nous avons évalué l’efficacité clinique des stratégies existantes de traitement de maladies spécifiques et évalué l’efficacité de la prestation des soins de santé pour les maladies multi-morbides.

Méthode:

Pour le contexte, nous avons configuré les lieux où logent des patients qui se sont présentés 552 062 fois au service d’urgence de l’hôpital de la zone couverte (2005-2013). Les données agrégées de 22 519 arrestations de personnes souffrant de maladie mentale ont été fournies par le service de police de Vancouver (2009-2015). La stratégie principale était une étude de cohorte longitudinale de 375 personnes vivant dans le DTES (2008-2015). Nous avons analysé la mortalité, et évalué l’efficacité de la prestation des services de santé et cliniques pour : l’infection à virus de l’immunodéficience humaine ou à virus de l’hépatite C, la dépendance aux opioïdes, et la psychose.

Résultats:

La configuration a confirmé l’association entre la pauvreté et le plus grand nombre de visites à l’urgence liées à l’utilisation de substances et à la maladie mentale. Le changement annuel des arrestations de la police ne différait pas entre le DTES et d’autres districts de police. Durant 1581 années-personnes d’observation de cohorte, le taux de mortalité normalisé était de 8,43 (intervalle de confiance à 95 % 6,19 à 11,50). Les visites à un médecin étaient fréquentes (84,3 % des participants sur 6 mois). L’efficacité du traitement clinique était la plus élevée pour le VIH/sida, intermédiaire pour la dépendance aux opioïdes, et faible pour la psychose. Les mécanismes de la prestation de services ont présenté des exemples de mauvais accès, de médiocre observance du traitement, et de peu d’effet sur les maladies multi-morbides.

Conclusions:

L’efficacité clinique était variable, et la prestation de services pour les maladies spécifiques semblait avoir peu d’effet sur la multi-morbidité. Il faut peut-être mettre en œuvre de nouveaux modèles de soins.

Vancouver, Canada, is rated as one of the world’s most “liveable” cities.1 However, in the impoverished Downtown Eastside (DTES) neighborhood, significant income disparity and social marginalization fuel extensive health challenges, including epidemics of HIV, hepatitis C (HCV), and opioid and stimulant drug use. Similar situations exist in other Canadian cities.2,3 Living in marginal housing in impoverished environments may be more prevalent than homelessness and may create comparably severe consequences.4–6 Even in countries such as Canada, where access to care is not dependent on income, use of health services can shift from community-based to dependency on the hospital emergency room.7 For mental illness, police officers may become the first responders if community care is inadequate to provide early intervention to prevent acute exacerbations. In this context, the extent to which health care delivery is effectively adapted to the needs of those most vulnerable, or those living in poverty, requires examination.8,9

For HIV and opioid addictions, innovative, well-resourced treatment delivery platforms and harm-reduction initiatives for injection drug use have made specific and significant impacts on HIV transmission and on mortality related to opioid overdose.10,11 However, disproportionately high all-cause mortality persists in the DTES.12 Substance use can form a high-mortality link between mental and physical illness.13 Scaling up and improving treatment for HCV and HIV requires understanding behaviors that create transmission risk and the possibility of reinfection or development of drug resistance.14,15 Psychotic illness itself presents unique challenges in engaging patients and, along with other mental illnesses, contributes to excess early mortality in international studies16–18 as well as in the DTES.19,20

Successful implementation of clinically effective interventions may require collaborative interprofessional teams specifically skilled in providing care for the patient’s condition, anticipated complications, and related comorbidities.21,22 Development of integrated interventions to care for complex and often vulnerable patients lags behind the availability of clinically effective, but illness-specific treatments.6,15,23 The Hotel Study was initiated in Vancouver’s DTES to provide an evidence base related to multimorbidity in a community cohort of homeless or marginally housed people. Published findings include a description of the cohort at an initial stage, an assessment of substance use–related harm and brain imaging findings, and a description of cognitive findings.19,24–30 In the complex neighborhood environment, the impact of existing treatment strategies (largely designed for specific illnesses) on co-occurring or multimorbid illnesses in individual patients is unclear. As examples, participants may receive HIV care through the Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS and opioid replacement therapy from their community-based “methadone doctor.” The objectives of the present series of analyses were, first, to provide a context by examining emergency room utilization and police apprehensions of the mentally ill and, second, to undertake new analyses using an overlapping timeframe in Hotel Study cohort participants. We aimed to update the mortality findings for the cohort throughout the period of observation. For examples from each of 3 illness categories (viral infection, opioid dependence, psychosis), we examined the prevalence of treatment and, where administered, the potential impacts for comorbid illness(es) as a test of overall system effectiveness.

Method

Setting

The DTES neighborhood of Vancouver, Canada, provides accommodation for approximately 3800 people in subsidized, single room occupancy (SRO) hotels. The DTES is also the site of the Downtown Community Court (DCC), which processes 2500 cases per year. One university teaching hospital provides most inpatient and emergency services to the local health authority (LHA) catchment area that includes the DTES (LHA 161) and the adjacent LHA 162.

Mapping Poverty and Emergency Room Visits

Three indices of poverty (dwellings in disrepair, median after-tax income, and subsidized housing) from 2011 Canadian Census National Household Survey data were mapped onto City Center and Downtown Eastside local health authority areas. Emergency department staff from the general hospital routinely recorded the reason for visits and the patients’ addresses. This information was obtained for 552,062 visits from 2005 to 2013. These included neurological (39,559; used here as a reference illness type), substance-related (21,161), and mental health–related (31,914) visits. Using addresses, visit origins were mapped by postal code of the patient’s dwelling to census dissemination areas; 40,760 visits mapped to City Center and to the DTES. For mapping, the number of visits for each illness type was divided by the population in the census dissemination area.

Police Apprehensions of People Displaying Signs of Mental Illness

Section 28 of the Mental Health Act of the Province of British Columbia allows police officers to apprehend and take to a physician any individual who “a) is acting in a manner likely to endanger that person’s own safety or the safety of others, and b) is apparently a person with a mental disorder.”31 A completed Medical certificate (Form 4) allows involuntary admission and may involve a police apprehension. A judicial order (Form 10) allows apprehension of a person with an apparent mental disorder, and a Director’s Warrant (Form 21) allows apprehension of a patient on leave and liable for recall. All Vancouver police officers receive training in recognizing mental illness. For 2009 to 2015, the Vancouver Police Department provided aggregate values from its records of the total number of all apprehensions of people with mental disorders and of distinct individuals with 1 or more apprehensions per year.

Cohort Study Design, Assessments, and Study Participants

Participants were recruited from DTES SROs (n = 310) and the DCC (n = 65) from November 13, 2008, to August 27, 2012. Access to care and the health care delivery system was stable during this period of time. Participants were required to be 18 years of age or older and capable of providing written informed consent. The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Board of the University of British Columbia and by Simon Fraser University.

Participants took part in comprehensive, baseline assessments of addiction and mental illness, with focused studies of viral infection and neurological illness (see Supplemental Table S1).19 Diagnoses were made using DSM-IV criteria; structured assessments and rating scales were used to assess illness severity. Neuropsychological testing and magnetic resonance imaging were carried out. Serology for HIV and HCV was obtained, with qualitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) testing for active infection in those with positive HCV serology. Health service utilization was assessed using questions from the Canadian Community Health Survey,32 modified for separate inquiries on mental illness/substance use and physical illness. Mortality was investigated though obtaining coroner’s reports and hospital records.

The baseline assessments were followed by brief, monthly visits and comprehensive evaluations annually. Behaviors associated with transmitting HIV or HCV were assessed with the Maudsley Addiction Profile for the 30 days prior to study entry. Assessments of clinical treatment effectiveness were illness specific (Supplemental Table S2). Briefly, the British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS provided viral suppression results for assessment of treatment effectiveness of HIV with antiretrovirals. For HCV, histories of treatment with interferon were obtained, and viral clearance was assessed with qPCR. For opioid dependence, assessments included a history of methadone use, self-reported number of days using nonprescribed opioids for the 4 weeks preceding study entry, and urine drug screen results at study entry. For psychosis, a history of treatment with antipsychotic medication was noted. For severity of psychosis at study entry, the summed scores of 5 key items from the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (items P1 delusions, P2 conceptual disorganization, P3 hallucinations, P6 suspiciousness, G9 unusual thought content) were used.33

The effectiveness of the service delivery system was assessed through reviewing whether treatments (antiretrovirals, methadone, or antipsychotic drugs) were received by participants with 1 or more of the 3 target illness categories during the 4 weeks prior to study entry (Supplemental Table S2). The presence or absence of 12 possible illnesses common in the cohort (8 physical and 4 mental or addiction, Table 1) was assessed in each participant as a measure of impact on multimorbidity.19 For community-based treatment, assessments of health service utilization over the previous month were carried out for 6 months. Self-report of outpatient and emergency department visits was reliable in a patient sample similar to ours.34

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants at study baseline and mortality (N = 375).

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 43.7 (36.5-50.5) |

| Female sex, no. (%) | 82 (21.9) |

| Ethnicity, no. (%) | |

| White | 227 (60.5) |

| Black | 9 (2.4) |

| Asian | 3 (0.8) |

| Aboriginal | 102 (27.2) |

| Mixed/other | 34 (9.1) |

| Lifetime history of homelessness, no. (%) | 256 (68.3) |

| Visit with family physician, no./total no. (%)a | 311/369 (84.3) |

| Physical illness, no./total no. (%) | |

| HIV seropositive | 64/361 (17.7) |

| Hepatitis C virus qPCR positive | 180/351 (51.3) |

| Hepatitis B virus surface antigen positive | 5/360 (1.4) |

| Movement disorderb | 66/343 (19.2) |

| Traumatic brain injuryc | 41/371 (11.0) |

| Seizures | 33/373 (8.8) |

| Clinical cognitive impairment diagnosis | 33/375 (8.8) |

| Brain infarction on MRI | 30/297 (10.1) |

| Mental illness, no. (%) | |

| Psychotic disorder | 177 (47.2) |

| Substance-induced psychosis | 64 (17.1) |

| Functional psychosisd | 63 (16.8) |

| Psychosis not otherwise specified | 48 (12.8) |

| Psychosis due to a general medical conditione | 2 (0.5) |

| Alcohol dependence | 67 (17.7) |

| Stimulant dependence | 307 (81.9) |

| Cocaine dependence | 254 (67.7) |

| Methamphetamine dependence | 95 (25.3) |

| Opioid dependence | 155 (41.3) |

| Heroin dependence | 138 (36.8) |

| Other opioid dependence | 72 (19.2) |

| Multimorbid illnesses, no. median (IQR)f | 3 (2-4) |

| Mortality during study, no. (%) | 40 (10.7) |

| Age at death, years, median (IQR) | 52.7 (45.8-58.6) |

| Causes of death, no. (%) | |

| Physical illness | 22 (55.0) |

| Accidental drug overdose | 9 (22.5) |

| Trauma | 4 (10.0) |

| Suicide | 1 (2.5) |

| Undetermined | 4 (10.0) |

IQR = interquartile range; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; qPCR = qualitative polymerase chain reaction.

aThe data were obtained from 369 participants, reported for the first 6 months of study follow-up.

bMovement disorder: Parkinsonism, dyskinesia, or akathisia defined as a score of moderate or more on the Extrapyramidal Symptoms Rating Scale or the Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale.

cEvidence of previous traumatic brain injury (TBI) on MRI for 23 participants; or history of TBI (loss of consciousness ≥5 minutes or confusion ≥1 day) and persistent symptoms referable to TBI including seizures or organic personality disorder in 18 participants.

dDiagnoses of schizophrenia in 29, schizoaffective disorder in 20, bipolar with psychosis in 10, depression with psychosis in 2, and delusional disorder in 2 participants.

eDiagnoses of postanoxic- and of interferon-related psychosis in 1 participant each.

fMaximum 12, comprised of 8 physical illnesses, and 4 major mental illnesses listed above in the table.

Statistical Analyses

Annual rates of change in numbers of total police apprehensions for mental illness were compared between the DTES policing district and all other Vancouver districts using a Wilcoxon test.

The standardized mortality ratio (SMR) for the cohort was determined using the indirect method of standardization. The SMR was calculated as the ratio of the observed number of deaths to the number of deaths expected if the cohort experienced the same age- and sex-specific mortality rates as the general Canadian population in 2009. The Boice-Monson method was used to calculate the 95% confidence interval.

Frequencies of behaviors associated with transmitting HIV or HCV were compared between those with or without infection by use of chi-square tests. Previous antiretroviral treatment for HIV was nearly universal, so clinical effectiveness analysis was descriptive and based on optimal viral suppression results following initiation of treatment. For HCV, chi-square test was used to compare viral clearance between those previously treated with interferon and those never treated. For opioid dependence and psychosis, outcomes were compared between those who received treatment in the 4 weeks prior to study entry and those with untreated illness, through use of Wilcoxon tests for continuous measures that were not normally distributed and chi-square tests for categorical outcomes.

The effectiveness of the service delivery systems was described by calculating the proportions of patients eligible for treatment relative to the numbers actually treated and by determining adherence to treatment in the 4 weeks prior to study entry. The possibility that accessing services for illness-specific treatments (antiretrovirals, methadone, or antipsychotics) could have a beneficial effect on multimorbid illness was analysed by comparing multimorbidity in those treated or untreated (but eligible) by use of Wilcoxon tests.

For analysis of community-based treatment, utilization of the hospital emergency department in the first 6 months of the study was compared between those who had consulted a physician in the month prior to entering the study and those who had not, through use of Wilcoxon tests.

Results

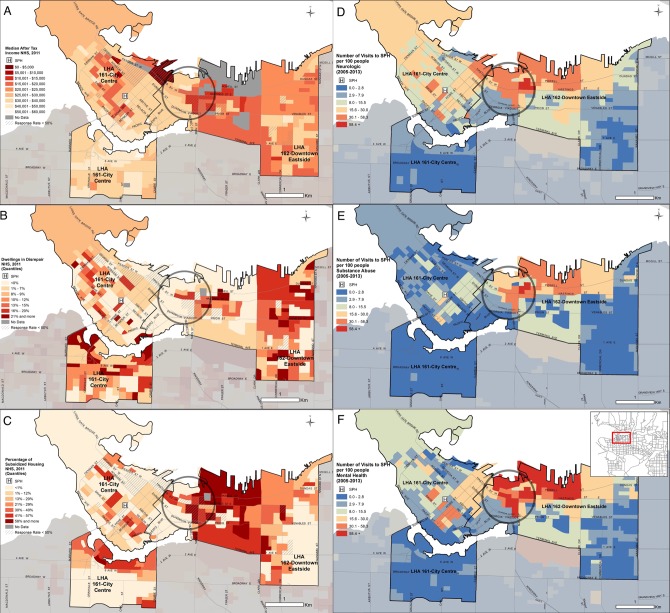

The DTES (LHA 162) is clearly identified as a neighborhood with a triad of low income, large numbers of dwellings in disrepair, and high rates of subsidized housing (Figure 1). Associated with this distribution of markers of poverty in the northwestern quadrant of LHA 162 are progressively higher rates of seeking emergency department care for neurological illness, for substance use disorders, and for mental illness.

Figure 1.

Relationship of measures of poverty and emergency department utilization for specific disorders. Statistics are kept for local health authorities (LHA), 2 of which are depicted in the figure. Emergency department visits are illustrated for the St. Paul’s Hospital (SPH, “H”) in the center of the northern part of LHA 161. This hospital serves the northern part of LHA 161 and LHA 162; a different hospital is closer to the southern part of LHA 161. The ring in LHA 162 delineates the area of recruitment where 95% of participants in the Hotel Study lived. The distribution of measures of poverty includes (A) the median after-tax income assessed in the National Household Survey (NHS) in 2011, (B) dwellings in disrepair, and (C) the percentage of subsidized housing. The distribution of people seeking emergency department care (per 100 living in a census dissemination area) includes (D) neurological disorder visits, (E) substance misuse visits, and (F) mental health related visits, with an insert map placing the region within the lower mainland area of British Columbia.

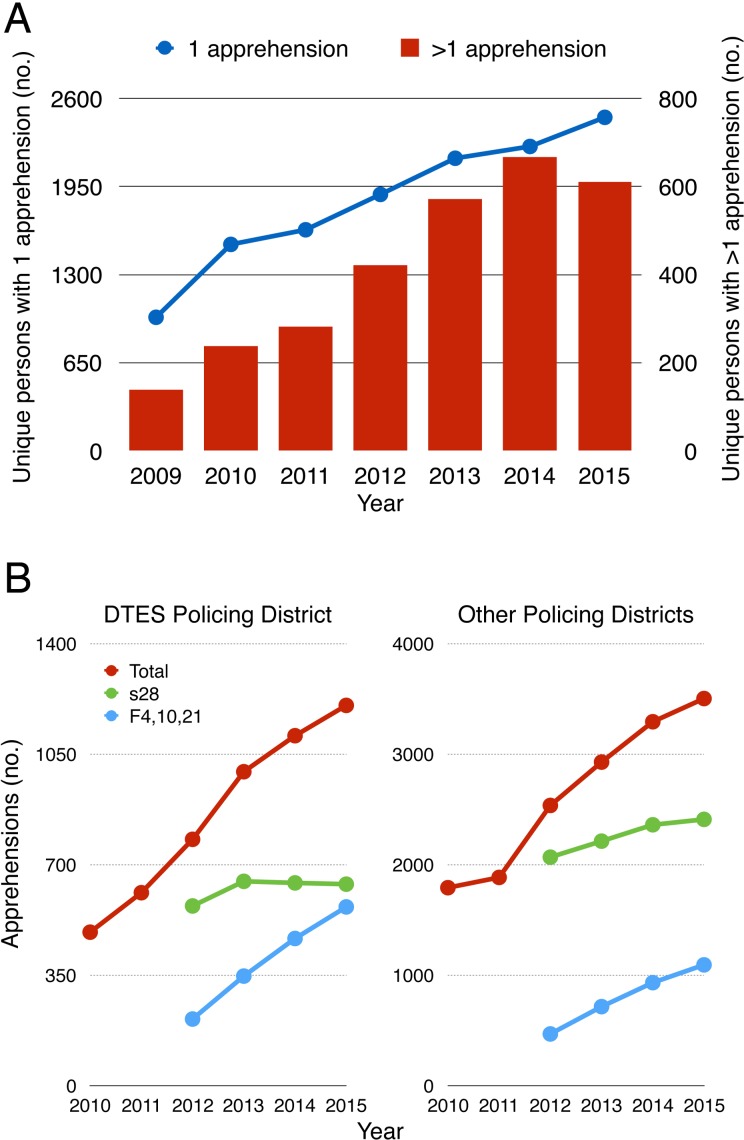

Citywide from 2009 to 2015, the police department carried out 22,519 apprehensions of people with mental illness and transported them to hospital. The proportion of persons with multiple apprehensions appears to be stabilizing at approximately 20% (Figure 2A). The mean time between first and second apprehension was 68.7 days (SD 4.9) over this 7-year period. Considering all types of apprehensions for mental illness, we found no statistically significant difference between annual rates of change in the DTES (median = 25.7, interquartile range [IQR] 10.1-27.6) compared with other policing districts (median = 14.8, IQR 5.8-25.0, Wilcoxon S = 3.5, P = 0.44, see Figure 2B) from 2010 to 2015. However, between 2012 and 2015, a shift in the ratio of apprehensions initiated by the police (section 28) and those initiated by mental health providers (Form 4, 10, 21) is apparent, approaching 1:1 in the DTES and remaining at more than 2:1 in other policing districts (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Trends in police apprehensions related to mental illness. (A) Numbers of unique individuals with a single apprehension in a year are shown with the gray line and the left y-axis. Numbers of unique individuals with more than 1 apprehension in the same year are shown as black bars and the right y-axis. (B) Data for total apprehensions, apprehensions initiated by police (s28), and apprehensions initiated by mental health care providers (F4, 10, 21). The left panel shows the relative increase in care provider-initiated apprehensions in the Downtown Eastside (DTES) relative to other policing districts.

For the Hotel cohort study, of approximately 515 potential participants, 375 (72.8%) agreed to join (Supplemental Figure S1). Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants appear in Table 1. In the first 6 months of the study, 311 of 369 (84.3%) consulted with a family physician. During 1581 person-years of observation, 40 of 375 (10.7%) of participants died, yielding a crude mortality rate of 2.53 per 100 person-years. Compared with age- and sex-matched Canadian population data from 2009, the SMR was 8.43 (95% confidence interval [CI], 6.19 to 11.50). Causes of death appear in Supplemental Table S3.

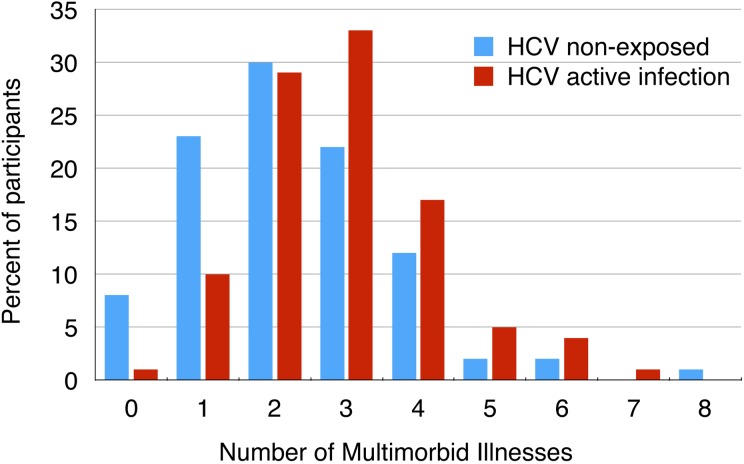

Higher rates of injection drug use in the past month were reported by those with HIV (41 of 64, 64.1%) or HCV (130 of 180, 72.2%) compared with uninfected individuals (50 of 154, 32.5%, chi-square = 50.35, P < 0.001, Supplemental Table S4). Unprotected sex and needle or crack pipe sharing did not differ between groups. For the 64 participants with HIV at baseline and the 4 later conversions, access and initiation of antiretroviral treatment were high, with effective viral suppression (Table 2 and Supplemental Table S5). However, successful treatment was often many years prior. Greater than 95% adherence in the first year of treatment was attained by only 30 of 63 (47.6%), and not all participants remained on treatment by the time of study entry. For those taking antiretrovirals, adherence in the 4 weeks prior to study entry was high. High-risk behaviors (Supplemental Table S6) did not differ between those taking antiretrovirals and those untreated. The number of multimorbid illnesses did not differ according to treatment status. Treatment for HIV was clinically effective; however, service delivery did not perform well over time and had no apparent impact on injection drug use or multimorbid illness. For those with HCV, the interferon-free direct-acting antivirals were not available at the time of recruitment. Of those few participants previously treated with interferon, more were qPCR negative than the untreated group (Table 2). To assess treatment needs, we examined multimorbid illness (maximum 11, excludes HCV) in the 180-participant HCV active-infection group compared with 116 nonexposed participants (Figure 3). The number of illnesses in the active infection group (median = 3, IQR 2-4, excluding HCV) was greater than that in the HCV seronegative group (median = 2, IQR 1-3, Wilcoxon z = 4.14, P < 0.001). To summarize, interferon treatment for HCV was much less effective than HIV treatment, and a new service delivery strategy for interferon-free direct-acting antivirals may need to be developed for multimorbid illness.

Table 2.

Clinical treatment, and service delivery effectiveness at study entry.

| Treated | Untreated | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical treatment effectiveness | |||

| HIV and antiretroviral treatment | |||

| Antiretrovirals ever initiated | 64/68 (94.1) | ||

| Ever achieved virologic suppressiona | 60/63 (95.2) | ||

| HCV and past interferon treatment | |||

| qPCR negative | 9/19 (47.4) | 36/160 (22.5) | 0.03 |

| Opioid dependence and methadone treatmentb | |||

| Taking prescribed methadone, no. (%) | 126/200 (64.0) | ||

| Methadone used in the past | 124/126 (98.4) | 58/74 (78.4) | <0.001 |

| Daily use of heroin, no. (%) | 18/126 (14.3) | 30/72 (41.7) | <0.001 |

| Heroin use, median days (IQR) | 2 (0-16) | 16 (1-28) | <0.001 |

| Urine drug screen positive opioids, no. (%)c | 66/115 (57.4) | 52/59 (88.1) | <0.001 |

| Psychotic disorders and antipsychotic treatmentd | |||

| Taking antipsychotics, no. (%) | 55/173 (31.8) | ||

| Antipsychotics used in the past | 44/55 (80.0) | 21/118 (17.8) | <0.001 |

| Severity of psychosis score, median (IQR) | 15 (9-21) | 13 (10-17) | 0.49 |

| Health service delivery effectiveness | |||

| HIV and antiretroviral treatment | |||

| Taking ARVs at study entrye | 38/62 (61.3) | ||

| ARV adherence (entry), median days (IQR)f | 28 (28-28) | ||

| Multimorbid illnesses, median no. (IQR)g | 3 (2-4) | 3 (2-4) | 0.73 |

| Opioid dependence and methadone treatment | |||

| Methadone adherence, median days (IQR)f | 28 (28-28) | ||

| Powder cocaine use, median days (IQR)h | 0 (0-4) | 0 (0-4) | 1.00 |

| Crack cocaine use, median days (IQR) | 9 (0-28) | 2 (0-27) | 0.13 |

| Urine drug screen positive cocaine, no. (%)i | 94/115 (81.7) | 46/59 (78.0) | 0.55 |

| Multimorbid illnesses, median no. (IQR)j | 3 (2-4) | 3 (2-4) | 0.84 |

| Psychotic disorders | |||

| Antipsychotic adherence, median days (IQR)f | 28 (27-28) | ||

| Powder cocaine use, median days (IQR)h | 0 (0-1) | 0 (0-0) | 0.84 |

| Crack cocaine use, median days (IQR) | 2 (0-25) | 2 (0-24) | 0.76 |

| Urine drug screen positive cocaine, no. (%)i | 33/45 (73.3) | 68/99 (68.7) | 0.57 |

| Multimorbid illnesses, median no. (IQR)k | 3 (2-4) | 3 (2-4) | 0.78 |

ARV = antiretroviral; HCV = hepatitis C; IQR = interquartile range; qPCR = qualitative polymerase chain reaction.

aData on clinical effectiveness of ARV treatment were missing for 1 patient.

bUse of methadone and heroin assessed over the 4 weeks prior to study entry.

cUrine drug screen done at study entry.

dUse of antipsychotic drugs assessed over the 4 weeks prior to study entry.

eData were missing on 2 patients with HIV at study entry.

fAdherence over the 4 weeks prior to entering study.

gMaximum number 11, excludes HIV.

hUse of cocaine assessed over the 4 weeks prior to study entry.

iUrine drug screens done at study entry.

jMaximum number 11, excludes opioid dependence.

kMaximum number 11, excludes psychotic disorder.

Figure 3.

Multimorbid illness and hepatitis C virus (HCV) active infection. Percentage of participants in HCV nonexposed group (N = 116) and HCV active infection group (N = 180) with multimorbid illnesses (11 possible, excludes HCV). Multimorbid illnesses assessed were psychosis, alcohol dependence, stimulant dependence, opioid dependence, movement disorder, traumatic brain injury, clinical cognitive impairment, seizures, cerebral infarction, HIV, hepatitis B virus (HBV), surface antigen positive.

Nearly two-thirds of those with opioid dependence received methadone treatment; 78% of those not being treated had received methadone in the past (Table 2). Statistically, measures of clinical effectiveness including the proportion using heroin daily, the number of days using heroin, and the proportion of urine drug tests positive for opioids all favored methadone over no replacement treatment. However, the majority of those taking methadone still had detectable opioids in urine. Adherence with methadone was high (Table 2), but methadone had no impact on cocaine use or on multimorbid illnesses. Methadone was clinically effective; however, service delivery was ineffective in decreasing cocaine use or multimorbid illness.

For psychotic disorders, less than one-third of affected participants were treated with antipsychotic drugs. In contrast to the high prevalence of previous treatment with methadone in opioid-dependent participants, only 18% of those with current, untreated psychosis had received antipsychotic drugs in the past (Table 2). There was no difference in baseline psychosis severity between those being treated and those untreated or between those treated with depot or oral antipsychotic drugs. For those taking antipsychotic drugs, adherence in the 4 weeks prior to baseline was high (Table 2) and did not differ between the 20 patients taking injectable depot antipsychotic drugs and the 35 taking oral drugs (t = 0.21, df = 53, P = 0.83). Of note, only 1 patient was prescribed clozapine (the only drug indicated for treatment-resistant schizophrenia). Antipsychotic drug treatment had no impact on cocaine use or on the number of multimorbid illnesses. Antipsychotic medication was the least effective of the 3 illness-specific treatment modalities analysed, and service delivery had little impact on multimorbidity.

At least 1 month of follow-up data were available for 350 of 375 participants, and of these, 225 (64.3%) reported seeing a physician in the month prior to baseline. Over the following 6 months, 70 (20.0%) had a physical illness emergency resulting in a hospital visit. There was no difference in the rates of emergency visits between those who had or had not consulted a physician in the month prior to baseline (45 of 225 consultation; 25 of 125 no consultation, chi-square = 0, P = 1.00). During the same time period, 28 (8.0%) had an addiction-related or mental illness–related emergency department visit. Those who had previously consulted a physician were more likely to seek mental illness or addiction emergency care than those who had not (25 of 225 consultation; 3 of 125 no consultation, chi-square = 9.9, P = 0.002).

Discussion

The challenges of delivering effective health care in an impoverished neighborhood in a large city of a high-income country share many features with global health problems.21,35 Infectious disease is prevalent and mortality is high, confirming administrative data.12 Behaviors that increase risk of disease transmission are most frequent among those with active infection. While access to medical care is high, long-term adherence with treatment is variable. Treatments display a range of clinical effectiveness, from very high for HIV to less than expected for psychotic disorders. None of the illness-specific delivery systems appeared to modify multimorbidity.

Our assessments of context revealed the expected association between poverty and substance dependence as well as psychosis. Improvement in community-based care for addiction and mental illness needs urgent attention and could be guided by mapping studies to identify neighborhoods with the greatest need for community-based interventions.36 Reliance of a health system on police officers as first responders for acute exacerbations of mental illness inevitably increases the risk of patient death by firearms. In the American setting, where access to firearms is much greater than in Canada, for patients with schizophrenia the SMR associated with legal interventions is 3.6.37 While the number of apprehensions by police in the DTES remains high, the shift to a greater proportion of apprehensions at the request of health care providers provides some suggestion of engagement of patients with the system of care. The Vancouver police force pioneered training officers for interacting with mentally ill people. For officers carrying out apprehensions, knowing beforehand that the situation will involve mental illness may reduce the risk of adverse interactions. Nonetheless, the observation that approximately 20% of apprehensions involved patients with more than 1 apprehension per year is an indication of poor effectiveness of clinical and service delivery.

In the Canadian system, access to physicians for medical care is high, even among the homeless.7 Access to community-based care did not appear to be problematic, consistent with other Canadian observations.7 Greater physician access was associated with greater use of emergency department care, as described in other reports.7

The clinical effectiveness of current HIV treatment was high in reducing viral load in the cohort; wide application of treatment in British Columbia has reduced the incidence of HIV.11 However, health service delivery did not fully support continued adherence in the cohort and did not affect concurrent illnesses. For HCV, challenges arise in implementing interferon-free, direct-acting antivirals for patients who are at high risk of reinfection due to substance use.38 Modeling suggests that to eliminate HCV, wide implementation of interferon-free, direct-acting antivirals will need to be coupled with expanded harm reduction.39 Methadone replacement treatment for opioid dependence reduces use of heroin and maintains engagement with addiction treatment.40 Although we observed beneficial effects of methadone treatment on the direct target of heroin use, the possible broader benefits of the methadone service delivery strategy on concurrent illnesses were either too small to detect or absent in the present cohort. Patients suffering from psychotic disorders were overrepresented here, similar to studies of homeless or precariously housed people worldwide.3,41–43 In our setting, antipsychotic treatment appeared less clinically effective than expected. Concurrent drug use may be a major contributor through its effects on dopaminergic systems and by providing a link to impulsive behaviors, creating risk for HIV or HCV transmission.44,45 Social mechanisms could also play a major role, as poverty and genomic variation appear to create similar magnitudes of increased risk for schizophrenia.46 Antipsychotic treatment was underused relative to antiretrovirals or methadone; the relatively low history of treatment suggests that underdiagnosis of psychosis in the community may be longstanding. The service delivery approach for medication treatment of psychosis had no demonstrable effect on stimulant drug use or multimorbid illnesses.

Like many studies of health service effectiveness, this study is limited in the extent to which the findings can be generalized to other systems or settings. Important contexts for the Hotel Study are the universal health care system in Canada, the relative ease of access to harmful drugs in the DTES, and the availability of a social safety net, limited though it may be. The majority of our participants lived in marginal housing, and the generalizability of our findings to those living in homelessness may require additional study. This is particularly true for itinerant populations, as the majority of our cohort were still living in the DTES during follow-up.19

Outside of geriatric medicine, the role of multimorbidity in designing health care interventions and assessing outcomes has only recently received greater attention.47–49 Recommendations regarding improvement in care for patients with mental and physical multimorbidity include better training, more thorough patient assessment, and integration between primary and (multi) specialist care.50,51 The interaction between multimorbidity and social marginalization may require better coordination between provision of health care and housing and may demand policy changes.47 New models of integrated service delivery focus on improving value (outcome per dollar spent), creating integrated practice units (that treat a primary problem as well as related illnesses, complications, and related circumstances), and relentlessly measuring individual patient health outcomes, not only service utilization.52–54

Conclusions

Through studying a cohort and a neighborhood in Vancouver, Canada, we describe a series of challenges in health delivery that mirror those in global health initiatives. Although several of the interventions we monitored were effective against their specific targets, they had little impact on multimorbidity, known to be associated with socioeconomic deprivation.49 System change may require acknowledgement of the importance of behavioral health, recognition that a cycle of care needs to include complications and comorbidities, and integration of specialty and primary care for complex illnesses.21

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: Dr. Honer has received consulting fees or sat on advisory boards for In Silico, Eli Lilly, Roche, Lundbeck, and Otsuka. Dr. Montaner has received grant support from Abbott, Biolytical, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Merck, and ViiV Healthcare. Dr. Barr has received consulting fees or sat on advisory boards for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, and Roche. Dr. Procyshyn has received speaking and advisory board fees from Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka, and Sunovion and was a member of speaker’s bureaus for AstraZeneca, Janssen, Lundbeck, and Otsuka. Dr. Krausz has received grant support from Bell Canada, CIHR, the Mental Health Commission of Canada, the Canadian Center of Substance Abuse, and the Innerchange Foundation. Dr. MacEwan has received speaking or consulting fees or sat on advisory boards for Apotex, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, and Sunovion and has received research grant support from Janssen. Dr. Rauscher has received advisory board fees from Hofmann-La Roche. Mr. Tran, Mr. Nham, Mr. Cervantes-Larios, Ms. Jones, Ms. Gicas, and Ms. Buchanan declare no conflict of interest. Drs. Vila-Rodriguez, Leonova, Langheimer, Panenka, Lang, Thornton, Vertinsky, Schultz, Krajden, and Smith declare no conflict of interest.

Funding: Supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CBG-101827, MOP-137103) and the British Columbia Mental Health and Substance Use Services (an Agency of the Provincial Health Services Authority). A.R. was supported by a New Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (201109MSH-261306-183304) and the Canada Research Chairs Program. W.G.H. was supported by the Jack Bell Chair in Schizophrenia.

Supplemental Material: The online supplementary files are available at http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/suppl/10.1177/0706743717693781.

References

- 1. Economist Data Team. The world’s most “liveable” cities. Economist. 2015;1–3. Available from: http://www.economist.com/blogs/graphicdetail/2015/08/daily-chart-5

- 2. Hwang SW, Aubry T, Palepu A, et al. The health and housing in transition study: a longitudinal study of the health of homeless and vulnerably housed adults in three Canadian cities. Int J Public Health. 2011;56(6):609–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ganesh A, Campbell DJT, Hurley J, et al. High positive psychiatric screening rates in an urban homeless population. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58(6):353–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Argintaru N, Chambers C, Gogosis E, et al. A cross-sectional observational study of unmet health needs among homeless and vulnerably housed adults in three Canadian cities. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hwang SW, Wilkins R, Tjepkema M, et al. Mortality among residents of shelters, rooming houses, and hotels in Canada: 11 year follow-up study. Brit Med J. 2009;339:b4036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fazel S, Geddes JR, Kushel M. The health of homeless people in high-income countries: descriptive epidemiology, health consequences, and clinical and policy recommendations. Lancet. 2014;384(9953):1529–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hwang SW, Chambers C, Chiu S, et al. A comprehensive assessment of health care utilization among homeless adults under a system of universal health insurance. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(suppl 2):S294–S301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hart JT. The inverse care law. Lancet. 1971;1(7696):405–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hwang SW, Burns T. Health interventions for people who are homeless. Lancet. 2014;384(9953):1541–1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Marshall BDL, Milloy MJ, Wood E, et al. Reduction in overdose mortality after the opening of North America’s first medically supervised safer injecting facility: a retrospective population-based study. Lancet. 2011;377(9775):1429–1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Montaner JSG, Lima VD, Barrios R, et al. Association of highly active antiretroviral therapy coverage, population viral load, and yearly new HIV diagnoses in British Columbia, Canada: a population-based study. Lancet. 2010;376(9740):532–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Deans GD, Raffa JD, Lai C, et al. Mortality in a large community-based cohort of inner-city residents in Vancouver, Canada. CMAJ Open. 2013;1(2):E68–E76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Björkenstam E, Ljung R, Burström B, et al. Quality of medical care and excess mortality in psychiatric patients—a nationwide register-based study in Sweden. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e000778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Altice FL, Kamarulzaman A, Soriano VV, et al. Treatment of medical, psychiatric, and substance-use comorbidities in people infected with HIV who use drugs. Lancet. 2010;376(9738):367–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sockalingam S, Sheehan K, Feld JJ, et al. Psychiatric care during hepatitis C treatment: the changing role of psychiatrists in the era of direct-acting antivirals. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(6):512–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moussavi S, Chatterji S, Verdes E, et al. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):851–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382(9904):1575–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(4):334–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vila-Rodriguez F, Panenka WJ, Lang DJ, et al. The Hotel Study: multimorbidity in a community sample living in marginal housing. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(12):1413–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jones AA, Vila-Rodriguez F, Leonova O, et al. Mortality from treatable illnesses in marginally housed adults: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(8):e008876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kim JY, Farmer P, Porter ME. Redefining global health-care delivery. Lancet. 2013;382(9897):1060–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hong CS, Abrams MK, Ferris TG. Toward increased adoption of complex care management. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(6):491–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brezing C, Ferrara M, Freudenreich O. The syndemic illness of HIV and trauma: Implications for a trauma-informed model of care. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(2):107–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gicas KM, Vila-Rodriguez F, Paquet K, et al. Neurocognitive profiles of marginally housed persons with comorbid substance dependence, viral infection, and psychiatric illness. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2014;36(10):1009–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gicas KM, Giesbrecht CJ, Panenka WJ, et al. Structural brain markers are differentially associated with neurocognitive profiles in socially marginalized people with multimorbid illness. Neuropsychology. 2017;31(1):28–43. doi:10.1037/neu0000304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Willi TS, Barr AM, Gicas K, et al. Characterization of white matter integrity deficits in cocaine-dependent individuals with substance-induced psychosis compared with non-psychotic cocaine users [published online February 1, 2016]. Addiction Biol. doi:10.1111/adb.12363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Willi TS, Honer WG, Thornton AE, et al. Factors affecting severity of positive and negative symptoms of psychosis in a polysubstance using population with psychostimulant dependence. Psychiatry Res. 2016;240:336–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Willi TS, Lang DJ, Honer WG, et al. Subcortical grey matter alterations in cocaine dependent individuals with substance-induced psychosis compared to non-psychotic cocaine users. Schizophr Res. 2016;176(2-3):158–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Giesbrecht CJ, O’Rourke N, Leonova O, et al. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS): a three-factor model of psychopathology in marginally housed persons with substance dependence and psychiatric illness. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0151648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jones AA, Vila-Rodriguez F, Panenka WJ, et al. Personalized risk assessment of drug-related harm is associated with health outcomes. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e79754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Province of British Columbia: Guide to the Mental Health Act. 2005. Available from: http://www.health.gov.bc.ca/library/publications/year/2005/MentalHealthGuide.pdf

- 32. Statistics Canada. Canadian Community Health Survey, Cycle 1.2 Mental Health and Well-being. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chen EYH, Hui CLM, Lam MML, et al. Maintenance treatment with quetiapine versus discontinuation after one year of treatment in patients with remitted first episode psychosis: randomised controlled trial. Br Med J. 2010;341:c4024–c4024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hwang SW, Chambers C, Katic M. Accuracy of self-reported health care use in a population-based sample of homeless adults. Health Serv Res. 2016;51(1):282–301. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Farmer PE. Chronic infectious disease and the future of health care delivery. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(25):2424–2436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kirkbride JB, Jones PB, Ullrich S, et al. Social deprivation, inequality, and the neighborhood-level incidence of psychotic syndromes in East London. Schizophrenia Bull. 2014;40(1):169–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, et al. Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1172–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Grebely J, Prins M, Hellard M, et al. ; International Collaboration of Incident HIV and Hepatitis C in Injecting Cohorts (InC3). Hepatitis C virus clearance, reinfection, and persistence, with insights from studies of injecting drug users: towards a vaccine. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(5):408–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lima VD, Rozada I, Grebely J, et al. Are interferon-free direct-acting antivirals for the treatment of HCV enough to control the epidemic among people who inject drugs? PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0143836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, et al. Methadone maintenance therapy versus no opioid replacement therapy for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD002209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Keogh C, O’Brien KK, Hoban A, et al. Health and use of health services of people who are homeless and at risk of homelessness who receive free primary health care in Dublin. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yim LCL, Leung HCM, Chan WC, et al. Prevalence of mental illness among homeless people in Hong Kong. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0140940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fekadu A, Hanlon C, Gebre-Eyesus E, et al. Burden of mental disorders and unmet needs among street homeless people in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Med. 2014;12:138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Panenka WJ, Procyshyn RM, Lecomte T, et al. Methamphetamine use: a comprehensive review of molecular, preclinical and clinical findings. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;129(3):167–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Helleberg M, Pedersen MG, Pedersen CB, et al. Associations between HIV and schizophrenia and their effect on HIV treatment outcomes: a nationwide population-based cohort study in Denmark. Lancet HIV. 2015;2(8):e344–e350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Agerbo E, Sullivan PF, Vilhjálmsson BJ, et al. Polygenic risk score, parental socioeconomic status, family history of psychiatric disorders, and the risk for schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(7):635–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mercer SW, Gunn J, Bower P, et al. Managing patients with mental and physical multimorbidity. Brit Med J. 2012;345:e5559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gijsen R, Hoeymans N, Schellevis FG, et al. Causes and consequences of comorbidity: a review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(7):661–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2012;380(9836):37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cournos F, McKinnon K, Sullivan G. Schizophrenia and comorbid human immunodeficiency virus or hepatitis C virus. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(suppl 6):27–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Langan J, Mercer SW, Smith DJ. Multimorbidity and mental health: can psychiatry rise to the challenge? Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202:391–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Porter ME, Lee TH. From volume to value in health care: the work begins. JAMA. 2016;316(10):1047–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Porter ME, Larsson S, Lee TH. Standardizing patient outcomes measurement. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(6):504–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Porter ME. The strategy that will fix health care. Harvard Business Rev. 2013;91(10):50–70. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.