Abstract

Mild to severe forms of nervous system damage were exhibited by approximately 60–70% of diabetics. It is important to understand the association between type 2 diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer’s disease. The aim of the present work is to understand the bidirectional association between type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis, that was monitored by glycaemic status, lipid profile, amyloid beta 40 and 42 (Aβ40 and Aβ42), C-reactive protein, total creatine kinase, total lactate dehydrogenase, D-dimer and magnesium measurements, to assess the association between theses biochemical markers and each other, to estimate the possibility of utilizing the amyloid beta as biochemical marker of T2D in Alzheimer's patients, and to evaluate the effect of piracetam and memantine drugs on diabetes mellitus. This study involved 120 subjects divided into 20 healthy control (group I), 20 diabetic patients (group II), 20 Alzheimer’s patients (group III), 20 diabetic Alzheimer's patients with symptomatic treatment (group IV), 20 diabetic Alzheimer's patients treated with memantine (group V), and 20 diabetic Alzheimer's patients treated with piracetam (group VI). The demographic characteristics, diabetic index, and lipid profile were monitored. Plasma amyloid beta 40 and amyloid beta 42, C-reactive protein, total creatine kinase, total lactate dehydrogenase, D-dimer, and magnesium were assayed. The levels of amyloid beta 40 and amyloid beta 42 were significantly elevated in diabetic Alzheimer's patients with symptomatic treatment (group IV) compared to group II (by 50.5 and 7.5 fold, respectively) and group III (by 25.4 and 2.8 fold, respectively). In groups II, III, IV, V and VI, significant and positive associations were monitored between insulin and amyloid beta 40, amyloid beta 42, C-reactive protein, total creatine kinase, and D-dimer. Diabetic markers were significantly decreased in diabetic Alzheimer’s patients treated with anti-Alzheimer’s drugs (especially piracetam) compared to group IV. This study reveals the role of amyloid beta 40, amyloid beta 42, insulin, HbA1c, lipid profile disturbance, C-reactive protein, D-dimer, and magnesium in the bidirectional correlation between T2D and pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease, that is powered by their correlations, and therefore the possibility of utilizing Aβ as a biochemical marker of T2D in Alzheimer's patients is recommended.

Impact statement

Several aspects associated with T2D that contribute to AD and vice versa were investigated in this study. Additionally, this work reveals the role of Aβ40, Aβ42, insulin, HbA1c, lipid profile disturbance, CRP, D-dimer, and magnesium in the bidirectional association between T2D and the pathogenesis of AD, that is powered by their correlations, and therefore the possibility of utilizing Aβ as a biochemical marker of T2D in Alzheimer's patients is recommended. Furthermore, the ameloriating effect of anti-Alzheimer’s drugs on diabetes mellitus confirms this association. Hereafter, a new approach for treating insulin resistance and diabetes may be developed by new therapeutic potentials such as neutralization of Aβ by anti-Aβ antibodies.

Keywords: Type 2 diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid beta, C-reactive protein, total creatine kinase, total lactate dehydrogenase, D-dimer, Magnesium

Introduction

The widespread incidence of obesity and aging is instigating an epidemic of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D). Hyperglycaemia and hyperinsulinemia are triggered by insulin resistance in peripheral tissues.1 Protocols for the treatment and prevention of the diabetes mellitus (DM) complications have improved. Consequently, chronic hyperglycemia (DM) results in the emergence of new complications, including AD.2

The incidence of Alzheimer’s disease, the most common neurodegenerative disorder, increases with age. Various pathognomonic markers, such as loss of neurons, senile plaques formation developed from extracellular deposits of amyloid-beta (Aβ), aggregated hyperphosphorylated tau proteins forming intracellular neurofibrillary tangles, activation of microglia, and proliferation of astrocytes characterize AD. Amyloid-β is derived from amyloid precursor protein (APP) through cellular processing pathways mediating the excision of the Aβ region by the sequential action of β-secretase and γ-secretase enzymes in distinct subcellular compartments. β-secretase cleaves the ectodomain of APP, resulting in the release of APPsα and APPsβ (12 kDa). The fragment (12 KDa) may subject to the cleavage by γ-secretase within the hydrophobic transmembrane domain at alanine 712, valine 710, or threonine 713 to release 40, 42, or 43 residue Aβ peptides, respectively. These features are associated with alterations in neuronal synapses and mitochondrial dysfunction.3

The incidence and prevalence of T2D and AD increase with age. A clear association between T2D and an increased risk of developing AD have been shown by numerous epidemiological studies.4–6 Additionally, obesity, hyperinsulinemia, and metabolic syndrome (T2D-related conditions) are risk factors for AD. Increased risk for AD in diabetic patients has been demonstrated by studies specifically assessing the incidence of dementia in people with diabetes mellitus, adjusting for glycemic control, microvascular complications, and comorbidity (e.g. hypertension and stroke), where it is found that an excess risk for AD by 50% to 100% in adults with diabetes was revealed in 8 of 13 population-based studies. The aggregate relative risk of AD for people with diabetes was 1.5 (95% CI), in meta-analysis, with a total of 6184 people with diabetes and 38530 without diabetes. The exact mechanisms with clinical relevance are unclear. Many mechanisms have been suggested, such as insulin resistance and deficiency and impaired insulin receptor and insulin growth factor signalling, to result in advanced glycation end products that may induce cerebrovascular injury and vascular inflammation.7,8

C-reactive protein (CRP) is an annular, pentameric protein found in blood plasma whose levels rise in response to inflammation. It is an acute-phase protein of hepatic origin that increases following interleukin-6 secretion by macrophages and T cells. Its physiological role is to bind to lysophosphatidylcholine expressed on the surface of dead or dying cells (and some types of bacteria) in order to activate the complement system via the C1Q complex.9

D-dimer, a fibrin degradation product (or FDP), is a small protein fragment in the blood which is degraded by fibrinolysis after a blood clot. It contains two D fragments of the fibrin protein joined by a cross-link so it is called D-dimer.10

The aim of this work is to clarify the bidirectional association between T2D and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease, to evaluate the possibility of utilizing the Aβ as biochemical marker of T2D in Alzheimer's patients, and to study the effect of anti-Alzheimer’s drugs (piracetam and memantine) on diabetes mellitus.

Patients and methods

Patients

The current study included 120 subjects classified into the following six groups:

Group (I): Twenty healthy control subjects.

Group (II): Twenty previously diagnosed type 2 diabetic patients.

Group (III): Twenty previously diagnosed Alzheimer’s patients.

Group (IV): Twenty previously diagnosed type 2 diabetic and Alzheimer’s patients treated symptomatically.

Group (V): Twenty previously diagnosed type 2 diabetic and Alzheimer’s patients treated with memantine.

Group (VI): Twenty previously diagnosed type 2 diabetic and Alzheimer’s patients treated with piracetam.

The medication lines for diabetes were (not all groups of medications were taken by all patients): Insulins (short acting, intermediate, long acting, and basal insulins), sulfonylureas, secretagogue other than sulfonylureas (repaglinide), biguanides, TZDs, DPP-4 inhibitors (gliptins), oral alpha-glucosidase inhibitor (acarbose tablets). The medications prescribed for Alzheimer’s patients are: Piracetam, memantine, galantamine and rivastigmine. However, not all the medications are prescribed for all patients.

Full patient histories, including age, sex, special habits, occupation, diabetic duration and drug treatments were recorded. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated.11 Written informed consent was recieved from the patients, and this study was approved by the Ethical Committee of a tertiary hospital, KSA.

– Inclusion criteria: Patients suffering from T2D and/or AD aged more than 40 years.

– Exclusion criteria: Patients suffering from non-AD dementia, brain infarction, liver diseases, hypertension, heart diseases such as myocardial infarction, malignancy, autoimmune, renal, bone and muscular diseases, acute and chronic inflammatory diseases were excluded.

Sample collection and biochemical analysis

Blood samples were collected after an overnight fast. Fasting plasma glucose (FBG) was determined colorimetrically using a purchased kit, the human diagnostica liquicolor Test (Germany). The HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin, was chromatographically and colorimetrically assessed in whole blood using a kit obtained from BioSystems (Spain). Serum insulin was quantitatively measured by an ELISA kit obtained from Biosource Europe according to Temple et al.12 method. Serum triglyceride concentrations were colorimetrically determined using a Reactivos Spinreact Company (Spain) kit. Total cholesterol and high density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol concentrations were colorimetrically determined using Spinreact Company (Spain) kits. Serum low density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol levels were calculated according to Friedewald et al.’s13 formula (LDL-cholesterol = total cholesterol – triglycerides/5 –HDL-cholesterol). Plasma Aβ40 was quantitatively assessed according to the method of Galasko,14 and plasma Aβ42 was quantitatively estimated according to the method of Thakker et al.15 by ELISA using kits provided by DRG International, Inc. (USA). Plasma CRP was quantitatively assessed by ELISA using R and D Systems, Inc. (USA) kit, according to the method of Clearfield.16 Plasma total CK was quantitatively assessed by ELISA using a kit produced by Abbott Diagnostics (USA) according to Franck et al.17 method. Plasma total LDH was quantitatively assessed by ELISA using USCN Business Co., Ltd (Wuhan) kit according to Tang et al.18 method. Plasma D-dimer was quantitatively assessed by ELISA using USCN Business Co., Ltd (Wuhan) kit according to Nishank et al.19 method. Plasma magnesium was assessed by colorimetric method using a kit obtained from the Human Diagnostica Liquicolor Test (Germany) according to the method of Mann and Yoe.20

Statistical analysis

The data of the current study were analysed using SPSS (V. 21.0, IBM Corp., USA). For quantitative parametric measures, the data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Whereas, quantitative non-parametric measures were expressed as the median (percentiles range), the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to analyse the distribution of variables. For parametric data, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare different groups followed by post hoc Bonferroni tests to compare individual groups. For non-parametric data, comparisons between different groups were analysed using the Kruskall–Wallis test followed by comparing individual groups using the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test. Moreover, correlations between different parameters were evaluated using Pearson correlation and ranked Spearman correlation for parametric data and non-parametric data, respectively. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were plotted in which the value for sensitivity is plotted against 1-specificity. The overall accuracy of a biochemical marker to predict T2D in Alzheimer's patients is defined as the average of the sensitivity and specificity. The association between different parameters adjusted for the effect of other covariates and certain biochemical data was analysed using multiple linear stepwise regression analyses. P values ≤0.05 were considered significant.

Results

The BMI levels were significantly increased in groups III, IV, V and VI compared to the type 2 diabetic group (II). In addition, diabetic and Alzheimer's patients with symptomatic treatment, treated with memantine and piracetam (groups IV, V and VI), showed a longer duration of diabetes compared to the diabetic group (II), as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of healthy control (group I), diabetic patients (group II), Alzheimer's patients (group III), diabetic and Alzheimer's patients with symptomatic treatment (group IV), diabetic and Alzheimer's patients treated with memantine (group V), and diabetic and Alzheimer's patients treated with piracetam (group VI)

| Groups Clinical parameters | Group (I) | Group (II) | Group (III) | Group (IV) | Group (V) | Group (VI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Gender | ||||||

| -Male | 7 (35) | 7 (35) | 6 (30) | 7 (35) | 5 (25) | 9 (45) |

| -Female | 13 (65) | 13 (65) | 14 (70) | 13 (65) | 15 (75) | 11 (55) |

| Age (years) | 52.3 (47.2–68) | 52.5 (48.3–55.8) | 54 (48-81) | 55 (49–81.5) | 52 (46–80) | 53.8 (49.6–79) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25 ± 2.6 | 29.1 ± 2.9a,b | 31.5 ± 3.9a,b | 31.6 ± 3.5a,b | 31.1 ± 7a,b | 32 ± 5a,b |

| DM duration (years) | Nil | 9 (6–17) | Nil | 19 (10–21.5)b | 18 (15.8–22)b | 20 (14–23)b |

Results are expressed as a number (percentage), the mean ± SD and the median (percentiles range). N: Number of subjects;

BMI: Body mass index.

Significant difference from healthy control group (I).

Significant difference from diabetic group (II). P values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

The data presented in Table 2 revealed that there were significant increase in the FBG, HbA1c%, and insulin levels in the type 2 diabetic and Alzheimer's patients with symptomatic treatment (group IV) compared to the other groups (II and III). In addition, there were significant decrease in all diabetic markers in the diabetic and Alzheimer’s patients treated with anti-Alzheimer’s drugs (memantine and piracetam) (groups V and VI) compared to diabetic and Alzheimer's patients with symptomatic treatment (group IV). However, the FBG, HbA1c%, and insulin levels were significantly decreased in diabetic and Alzheimer’s patients treated with piracetam compared to diabetic and Alzheimer’s patients treated with memantine.

Table 2.

Diabetic markers of healthy control (group I), diabetic patients (group II), Alzheimer's patients (group III), diabetic and Alzheimer's patients with symptomatic treatment (group IV), diabetic and Alzheimer's patients treated with memantine (group V), and diabetic and Alzheimer's patients treated with piracetam (group VI)

| Groups Parameters | Group (I) | Group (II) | Group (III) | Group (IV) | Group (V) | Group (VI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBG (mmol/L) | 5.2 ± 0.4 | 8.4 ± 1.6a | 5 ± 0.8 | 20.5 ± 5a,b,c | 13.7 ± 2a,d | 10.5 ± 2a,d,e |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.4 ± 0.9 | 8.4 ± 1.4a | 5.7 ± 0.8 b | 11.2 ± 2.7 a,b,c | 7.9 ± 0.8a,d | 6.1 ± 0.8d,e |

| Insulin (µIU/mL) | 8.6 ± 2 | 26.4 ± 6.8a | 9.5 ± 2b | 76.3 ± 19a,b,c | 50.9 ± 6 a,d | 39 ± 9a,d,e |

Results are expressed as the mean ± SD.

FBG: Fasting blood glucose; HbA1c: glycated hemoglobin.

Significant difference from healthy control group (I).

Significant difference from the diabetic group (II).

Significant difference from the Alzheimer's group (III).

Significant difference from diabetic and Alzheimer's patients with the symptomatic treatment group (IV).

Significant difference from diabetic and Alzheimer's patients treated with the memantine group (V). P values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

The calculated means ± SD of total and LDL-cholesterol in diabetic and Alzheimer's patients with symptomatic treatment or who were treated with memantine or piracetam (groups IV, V, and VI) showed a significant increase compared to both the type 2 diabetic group (II) and Alzheimer's group (III), as shown in Table 3. Meanwhile, there was a significant elevation in the triglyceride levels in groups III, IV, V, and VI compared to type 2 diabetic patients. Moreover, the HDL-cholesterol levels in diabetic and Alzheimer's patients with symptomatic treatment or who were treated with memantine or piracetam (groups IV, V, and VI) showed a significant decrease compared to group III.

Table 3.

Lipid profile tests of healthy control (group I), diabetic patients (group II), Alzheimer's patients (group III), diabetic and Alzheimer's patients with symptomatic treatment (group IV), diabetic and Alzheimer's patients treated with memantine (group V), and diabetic and Alzheimer's patients treated with piracetam (group VI)

| Groups Parameters | Group (I) | Group (II) | Group(III) | Group (IV) | Group (V) | Group (VI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5 ± 0.4 | 14.1 ± 2.7a | 11 ± 0.9a,b | 18 ± 1.3a,b,c | 17.82 ± 1.5a,b,c | 19.2 ± 1.8a,b,c,d |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.7 ± 0.3 | 5 ± 1a | 6.8 ± 0.6a,b | 7.6 ± 1.5a,b | 8.22 ± 1.7a,b | 7.29 ± 1.3a,b |

| HDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 1 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 0.5b | 0.9 ± 0.2c | 0.89 ± 0.1c | 1.03 ± 0.2c |

| LDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 8 ± 1.8a | 6.7 ± 0.9a,b | 11.8 ± 1.5a,b,c | 12.09 ± 1.6a,b,c | 11.52 ± 1.9a,b,c |

Results are expressed as the mean ± SD.

HDL-cholesterol: high density lipoprotein-cholesterol; LDL-cholesterol: low density lipoprotein-cholesterol.

Significant difference from healthy control group (I).

Significant difference from the diabetic group (II).

Significant difference from the Alzheimer's group (III).

Significant difference from diabetic and Alzheimer's patients treated with the memantine group (V). P values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

Table 4 shows that the levels of Aβ40 and Aβ42 were elevated in diabetic and Alzheimer's patients with symptomatic treatment (group IV) compared to the type 2 diabetic group (II) (by 50.5 and 7.5 fold, respectively) and Alzheimer's group (III) (by 25.4 and 2.8 fold, respectively). In group III, the Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels were increased by 2 and 2.7 fold, respectively, compared to the type 2 diabetic group (II). In addition, Aβ40 and Aβ42 were elevated in the diabetic and Alzheimer's patients treated with memantine or piracetam (groups V and VI) compared to groups II and III. The CRP levels showed a significant increase in diabetic and Alzheimer's patients with symptomatic treatment or who were treated with memantine or piracetam (groups IV, V and VI) compared to both groups II and III. Additionally, there were significant increase in the levels of total CK and LDH in groups IV, V and VI compared to the type 2 diabetic group (I). Diabetic and Alzheimer's patients with symptomatic treatment or who were treated with memantine or piracetam (groups IV, V and VI) showed a significant increase in the D-dimer level compared to both groups II and III. On the other hand, the median (percentile range) of magnesium in diabetic and Alzheimer's patients with symptomatic treatment or who were treated with memantine or piracetam (groups IV, V and VI) was decreased compared to groups II and III.

Table 4.

Aβ40, Aβ42, CRP, total CK, total LDH, D-dimer and magnesium in healthy control (group I), diabetic patients (group II), Alzheimer's patients (group III), diabetic and Alzheimer's patients with symptomatic treatment (group IV), diabetic and Alzheimer's patients treated with memantine (group V), and diabetic and Alzheimer's patients treated with piracetam (group VI)

| Groups Parameters | Group (I) | Group (II) | Group(III) | Group (IV) | Group (V) | Group(VI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aβ40 (pg/mL) | 134.9 (112.9–153) | 136.5 (115–176.8) | 272 (250–290)a,b | 6900 (6360–7000)a,b,c | 6891.5 (6869–6909)a,b,c | 6880 (2858.5–6901)a,b,c |

| Aβ42 (pg/mL) | 26.9 (23–38) | 27.5 (15.5–44.8) | 73 (70–84)a,b | 206.5 (193.3–232.5)a,b,c | 200.9 (188– 217)a,b,c | 203 (200–214)a,b,c |

| (CRP mg/L) | 3.2 ± 0.4 | 7.5 ± 1.5a | 39.2 ± 9a | 124.3 ± 30a,b,c | 116.2 ± 20a,b,c | 112 ± 15a,b,c |

| Total CK (U/L) | 93.3 (85–100) | 95.1 (90.5–114.5) | 190.2 (180.9–229)a,b | 416 (247–534.8)a,b,c | 411 (250–531)a,b,c | 413.6 (263–533)a,b,c |

| Total LDH (U/L) | 255.9 ± 64 | 257 ± 20.7 | 275.5 ± 62.2a | 320.7 ± 80a,b | 315 ± 70a,b | 305 ± 65a,b |

| D-dimer (mg/L) | 0.5 (0.3–1) | 3.3 (3.1–4)a | 4 (3.5–11.3)a,b | 13.9 (6.3–19.3)a,b,c | 12.85 (5.35–18.5)a,b,c | 11.3 (3.5–18.5)a,b,c |

| Magnesium (mmol/L) | 0.9 (0.88–1.4) | 0.11 (0.09–0.61)a | 0.3 (0.08–0.84)a | 0.06 (0.05–0.56)a,b,c | 0.07 (0.06–0.65)a,b,c | 0.05 (0.03–0.46)a,b,c |

Results are expressed as the mean ± SD and median (percentile range).

Aβ40: amyloid β40; Aβ42: amyloid β42; CRP: c-reactive protein; total CK: total creatine kinase; total LDH: total lactate dehydrogenase.

Significant difference from healthy control group (I).

Significant difference from the diabetic group (II).

Significant difference from the Alzheimer's group (III). P values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

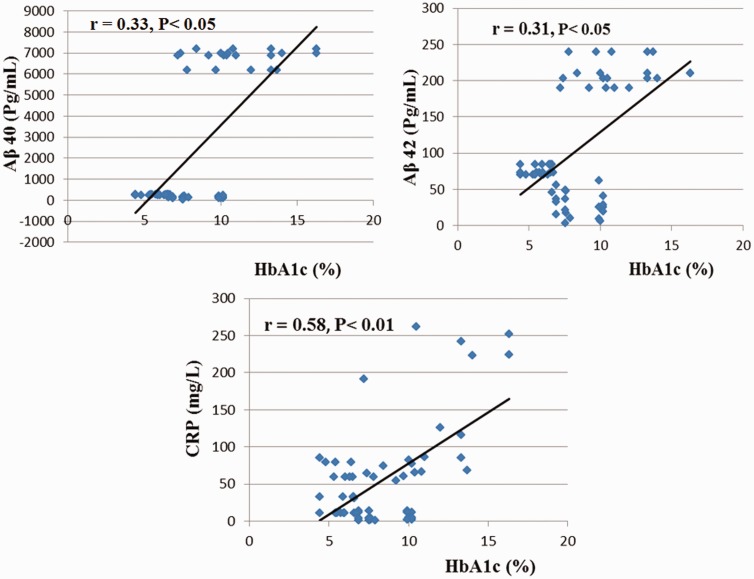

Positive correlations were detected between insulin and Aβ40, Aβ42, CRP, total CK and D-dimer. Meanwhile, the HbA1c and lipid profile (total cholesterol, triglycerides and LDL-cholesterol were positively correlated with Aβ40, Aβ42, CRP, and CK. The HbA1c was positively significantly correlated with total LDH. Additionally, positive significant correlations were detected between both total and LDL-cholesterol and D-dimer. However, the correlations between magnesium and HbA1c, insulin, total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol were negative but significant in groups II, III, IV, V, and VI as shown in Table 5 and Figure 1.

Table 5.

Correlations between diabetic markers, lipid profile and different investigated parameters in diabetic, Alzheimer's, diabetic and Alzheimer's patients with symptomatic treatment groups, diabetic and Alzheimer's patients treated with memantine, and diabetic and Alzheimer's patients treated with piracetam (II, III, IV, V and VI), n = 100

| Parameters Diabetic markers and lipid profile | Aβ40 (pg/mL) | Aβ42 (pg/mL) | CRP (mg/L) | Total CK (U/L) | Total LDH (U/L) | D-diner (Mg/L) | Mg (mmol/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HbA1c (%) | 0.33* | 0.31* | 0.58** | 0.37** | 0.35** | 0.15 | −0.5** |

| Insulin (µIU/mL) | 0.42** | 0.41** | 0.5** | 0.5** | 0.2 | 0.31* | −0.6** |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 0.47** | 0.43** | 0.47** | 0.5** | 0.2 | 0.38** | −0.57** |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 0.31* | 0.35** | 0.36** | 0.33** | 0.24 | 0.13 | −0.2 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mmol/L) | 0.52** | 0.51** | 0.59** | 0.59** | 0.13 | 0.3* | −0.58** |

Results are expressed as correlation coefficients (r).

HbA1c: glycated hemoglobin; LDL-cholesterol: Low density lipoprotein-cholesterol; Aβ40: Amyloid β40; Aβ42: Amyloid β42; CRP: C-reactive protein; total CK: Total creatine kinase; total LDH: Total lactate dehydrogenase.

P ≤ 0.05.

P ≤ 0.01.

Figure 1.

Correlations between HbA1c and Amyloid β40 (Aβ40), Amyloid β42 (Aβ42), and C-reactive protein (CRP) in diabetic, Alzheimer's, diabetic and Alzheimer's patients with symptomatic treatment groups, diabetic and Alzheimer's patients treated with memantine, and diabetic and Alzheimer's patients treated with piracetam (II, III IV, V, and VI), n = 100. (r): Correlation coefficient (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal)

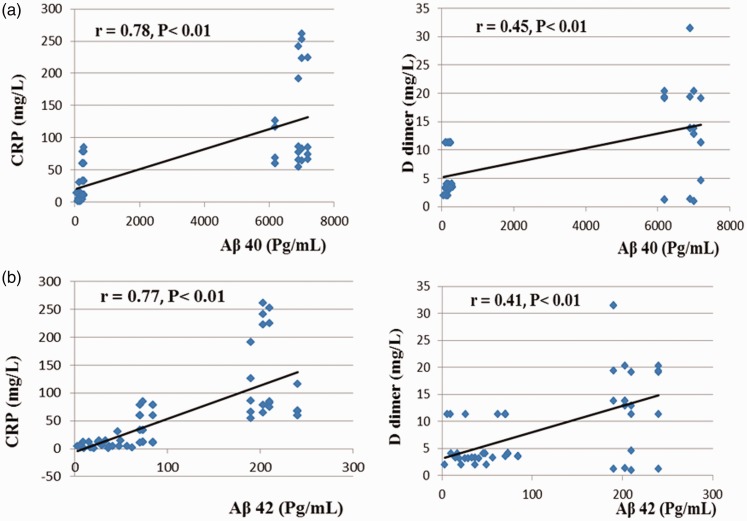

Positive correlations of Aβ40 and Aβ42 with CRP, total CK, and D-dimer were recorded in groups II, III, IV, V, and VI, as presented in Table 6 and Figure 2. However, there were negative correlations between magnesium and Aβ40 and Aβ42.

Table 6.

Correlations between Aβ40, Aβ42, and different investigated parameters in diabetic, Alzheimer's, diabetic and Alzheimer's patients with symptomatic treatment groups, diabetic and Alzheimer's patients treated with memantine, and diabetic and Alzheimer's patients treated with piracetam (II, III IV, V, and VI), n = 100

| Parameters Aβ40 and Aβ42 | Total CK (U/L) | Total LDH (U/L) | Mg (mmol/L) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aβ40 (pg\mL) | 0.87** | 0.23 | −0.66** |

| Aβ42 (pg\mL) | 0.84** | 0.2 | −0.63** |

Results are expressed as correlation coefficients (r).

Aβ40: amyloid β40; Aβ42: amyloid β42; CRP: C-reactive protein; total CK: total creatine kinase; total LDH: total lactate dehydrogenase.

P ≤ 0.01.

Figure 2.

Correlations between (a) Amyloid β40 (Aβ40) and C-reactive protein (CRP), and D-dimer in diabetic; (b) Amyloid β42 (Aβ42) and C-reactive protein (CRP), and D-dimer in diabetic Alzheimer's, diabetic and Alzheimer's patients with symptomatic treatment groups, diabetic and Alzheimer's patients treated with memantine, and diabetic and Alzheimer's patients treated with piracetam (II, III IV, V, and VI), n = 100. (r): Correlation coefficient (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal)

Furthermore, by using Aβ40 as the dependent variable and other investigated parameters as independent variables in multiple linear stepwise regression analysis, only the DM duration (β = 0.14, P < 0.01), HDL-cholesterol (β = −0.15, P < 0.01) and Aβ42 (β = 0.83, P < 0.01) remained correlated with Aβ40.

In multiple linear stepwise regression analysis using Aβ42 as the dependent variable and the other investigated parameters as independent variables, only the DM duration (β = 0.11, P < 0.05), HDL-cholesterol (β = −0.17, P < 0.01), and Aβ40 (β = 1.11, P < 0.01) remained correlated with Aβ42.

Additionally, by using CRP as the dependent variable and other investigated parameters as independent variables in multiple linear stepwise regression analysis, only Aβ40 (β = 1.1, P < 0.01) and total CK (β = 0.46, P < 0.01) remained correlated with CRP.

Moreover, by using HbA1c as the dependent variable and other investigated parameters as independent variables in multiple linear stepwise regression analysis, only HDL-cholesterol (β = − 0.65, P < 0.01) and CRP (β = 0.42, P < 0.01) remained associated with HbA1c.

Meanwhile, by using insulin as the dependent variable and other investigated parameters as independent variables in multiple linear stepwise regression analysis, only the DM duration (β = 0.32, P < 0.01) and Aβ40 (β = 0.62, P < 0.01) remained correlated with insulin. Eventually, by using total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol as dependent variables and other investigated parameters as independent variables in multiple linear stepwise regression analysis, only Aβ40 [(β = 0.76, P < 0.01), (β = 0.8, P < 0.01)] remained associated with total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol, respectively.

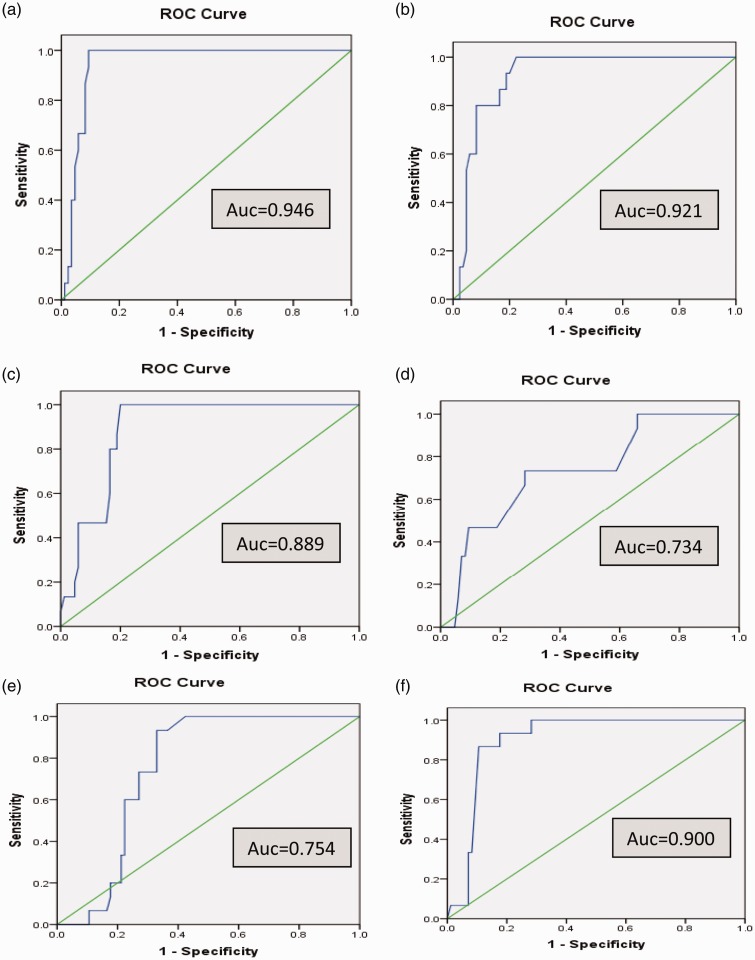

As illustrated in Figure 3, the receiver operator characteristic (ROC) analyses of the biochemical markers (Aβ40, Aβ42, CRP, D-dimer, total LDH, and CK); the areas under the curve (AUC) were 0.946, 0.921, 0.889, 0.734, 0.754, and 0.900, respectively and thus Aβ40 is the most reliable predictor of T2D in Alzheimer's patients.

Figure 3.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for (a) amyloid beta 40, (b) amyloid beta 42, (c) C-reactive protein, (d) D-dimer, (e) total lactate dehydrogenase and (f) total creatine kinase. AUC: Area under the curve (A color version of this figure is available in the online journal)

Discussion

The present research was planned to investigate the bidirectional association between T2D and AD pathogenesis. Recent epidemiological studies have demonstrated that individuals with T2D are two to four times more expected to develop AD.21

There were significant increase in the BMI levels in groups III, IV, V, and VI compared to the type 2 diabetic group (II). In obesity, brain health is affected by altered adipokine signaling. Changes in adipokine function may mitigate the pathogenesis of AD were suggested by both population and experimental studies.22 Higher BMI for participants with AD compared with non-AD participants with similar age was reported by a retrospective study with 18 year follow-up on women with dementia. The AD risk increased by 36% for every 1.0 increase in BMI at age 70 years, further highlighting the effect of overall adiposity on cognitive function at any given age.23

The present study revealed that FBG and HbA1c% levels were increased in diabetic and Alzheimer's patients treated symptomatically (group IV) compared to the diabetic group (II), and this was confirmed by the positive and significant correlations between HbA1c% and Aβ40, Aβ42, total CK and LDH. Volpe et al.24 stated that poor glycaemic control (HbA1c > 6.5%) was positively correlated with increased plasma levels of tumour necrosis factor alpha and vascular endothelial growth factor in T2D patients, reflecting the activation of innate immune cells and also high levels of malondialdehyde (MDA), indicating the presence of oxidative stress in T2D patients compared with healthy control individuals. Oxidative stress is a risk factor for development of AD. The damage to proteins and nucleic acids is mediated by excess of reactive oxygen/reactive nitrogen species, causing direct and deleterious consequences in AD. Additionally, oxidative stress induces advanced glycation end products by lipid peroxidation and glycoxidation, which are common in AD and serve as markers of disease progression.25 This was in agreement with the work of Ramirez et al.,26 who reported that higher levels of HbA1c % were correlated with increased risk of AD in an elderly population.

By measuring plasma lipid profiles, HbA1c % was positively significantly correlated with total cholesterol (r = 0.64, P < 0.01). Similarly, Regmi et al.27 revealed an increase in the prevalence of hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and high LDL-cholesterol levels in diabetic patients.

Several studies showed that in diabetic patients, insulin affects the liver production of apolipoprotein, regulates the lipoprotein lipase activity and cholesterol ester transport protein, causing dyslipidemia.28 Additionally, insulin resistance decreases the hepatic lipase activity and several processes in the biologically active lipoprotein lipase synthesis. In addition, hyperglycaemia elevates the cholesterol esters synthesis from HDL-cholesterol to VLDL-cholesterol particles; hence, denser LDL particles acquire a large proportion of these HDL-esters, more decreasing the level of HDL-cholesterol. Additionally, poor insulinization causes elevated lipolysis in adipocytes, leading to increased transport of fatty acid to the liver, and thus an increase in VLDL-cholesterol.29

Furthermore, the present results showed that there was a significant elevation in total cholesterol, triglycerides and LDL-cholesterol in group IV compared to groups II and III. There were significant positive correlations between total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol and Aβ40 and Aβ42. Approximately 30% of the total body’s cholesterol is in the brain, the most cholesterol-rich organ. Cholesterol is an crucial constituent of cell membranes in cholesterol, which plays an essential role in the progression and maintenance of plasticity and function of nerves. Neuronal plasticity is abnormal and neuronal function in turn is compromised in AD. A [beta] is produced by enzymatic cleavage of amyloid precursor protein (APP). [Gamma]-secretase cleaves APP in the core of the plasma membrane, so changes in the membrane lipid environment of [gamma]-secretase alter a [beta] production and hence AD pathogenesis. It has been supposed that an increase in membrane cholesterol may indirectly stimulate formation of neurofibrillary tangles. Other changes in AD that produce an oxidative imbalance have been attributed to toxicity related to amyloid-β and/or metal metabolism in the brain and peripheral tissues. There is evidence that high concentrations of oxidized derivatives of cholesterol (oxysterols) can stimulate neuronal apoptosis and exocytosis.30

The present results also demonstrated a significant increase in insulin levels in the diabetic and Alzheimer's group (IV) in comparison with the diabetic patients (group II). Also, there was a significant increase in the levels of Aβ40 and Aβ42 in diabetic and Alzheimer's patients with symptomatic treatment (group IV) compared to Alzheimer's patients (group III). These results are in agreement with the significant positive correlations between insulin and Aβ40 and Aβ42. The dysfunction in insulin production and insulin resistance could lead to a decline in acetylcholine levels, which may alter cognition and memory.31

Interestingly, insulin modifies amyloid beta levels by elevation its secretion or by cessation insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE). Because of the strong Aβ-degrading ability of IDE, a decrease in IDE activity in the brain can be a direct trigger of Aβ deposition to develop AD.32 Meanwhile, the current study coincides with the study of Zhao et al.33 which provided evidence that the reduction of IDE caused by altering the action of insulin in the brain might accelerate the onset of AD. By contrast, IDE has a role in maintaining insulin sensitivity in the body.32

It is very interesting to discover the mechanisms whereby AD affects the diabetic phenotype. Several hypotheses can be suggested. First, there is an alteration in the central control of metabolism of peripheral glucose in AD. Second, plasma amyloid beta may facilitate peripheral insulin resistance. Third, Aβ accumulates in the pancreas.34 Zhang et al.35 found that APP/presenilin 1 (PS1) transgenic AD mice with elevated plasma Aβ 40/42 levels have impaired hepatic insulin signalling and glucose/insulin tolerance and activation of the JAK2/STAT3/SOCS1 pathway. The JAK/STAT/SOCS pathway was recognized as downstream of inflammatory cytokines, by which inflammation elevates insulin resistance in the peripheral system.36 Zhang et al.37 extended this line of study by analysing the role of plasma Aβ in insulin resistance. Additionally, FBG, HbA1c%, and insulin levels were decreased in diabetic and Alzheimer’s patients who received anti-Alzheimer’s drugs (particularly piracetam) compared to diabetic and Alzheimer's patients who received symptomatic treatment (group IV). This result proved the ameliorating effect of anti-Alzheimer’s drugs on diabetes mellitus. All of the mentioned evidence confirms, without doubt, the bidirectional association between diabetes and AD pathogenesis.

Moreover there was a significant increase in CRP levels in diabetic and Alzheimer's patients who received symptomatic treatment (group IV) compared to group II and a positive significant correlation between HbA1c% and CRP. T2D is an inflammatory atherothrombotic condition. The inflammatory and metabolic factors are correlated with diabetes, such as hyperglycemia, modified lipoproteins, adipokines and free fatty acids, may cause CRP production, which participates in the systemic response to inflammation.38 Moreover, the present work showed significant positive correlations between CRP and Aβ40 and Aβ42, agree with the work of Yarchoan et al.,39 which provided evidence that chronic inflammatory diseases, such as AD, are associated with increases in plasma CRP.

Higher CRP levels were related to elevated levels of cerebral myoinositol (mI)/creatine (Cr), a biomarker of glial proliferation, due to increased blood brain barrier permeability, causing neurochemical changes linked to increased brain water diffusion and development of cognitive impairment conditions, such as AD. In addition, CRP is involved in autotoxic cascades causing decreased endothelial integrity, which may negatively impact cognition and cerebrovascular autoregulation.40

On the other hand, CRP is found to be associated with tangle and plaque pathology in the AD brain.41 C-reactive protein may also contribute to atherosclerotic processes and can increase the expression of adhesion molecules (intercellular and vascular cell adhesion molecules) in vascular endothelial cells in the human brain, explaining the positive significant correlation between CRP and D-dimer. Atherosclerosis of cerebral vessels may induce hypoperfusion and hypoxia, enhancing the production of Aβ peptide, which may promote the f atherosclerotic lesions formation through endothelial dysfunction and vascular oxidative stress leading to additional vascular damage.42

Furthermore, the current study found that there was a significant elevation in the plasma levels of D-dimer in group (IV) in comparison with group (II) and a positive significant correlation between HbA1c and D-dimer. Diabetes may be associated with enhanced lesion instability and atherosclerotic plaque rupture with superimposed thrombus formation. These changes are principally mediated by the insulin resistance, dysglycaemia and an elevated inflammatory state that alters the function of platelet, clot structure, and coagulation factors.43 The results of the present study showed a positive significant association between D-dimer and Aβ40 and Aβ42. Meanwhile, the present results are in agreement with the work of Carcaillon et al.,44 who stated that elevated D-dimer levels were associated with vascular dementia such as AD.

In the present study, it was proved that the levels of magnesium were diminshed in diabetic and Alzheimer's patients who recieved symptomatic treatment (group IV) compared to the diabetic group (II), and was confirmed by a negative significant correlation between HbA1c and magnesium. An increased prevalence of Mg deficit has been identified in type 2 diabetic patients, in particular with those having poorly controlled glycaemic profiles and a longer duration of the disease.45 The urinary Mg excretion and fasting blood glucose displayed an inverse relation with serum Mg levels. Increased glucose and insulin levels in the blood may increase urinary Mg excretion. Thus, hyperglycaemia decreases Mg tubular reabsorption.46

There were significant negative correlations between magnesium and Aβ40 and Aβ42. Magnesium plays a crucial role in many critical cellular processes, such as cellular respiration, oxidative phosphorylation, glycolysis and synthesis of protein. Decreased magnesium in the hippocampus is an important pathogenic factor in AD.47

Conclusion

We conclude that Aβ40, Aβ42, insulin, HbA1c, lipid profile disturbance, CRP, D-dimer, and magnesium have an important role in the bidirectional association between T2D and AD pathogenesis, which is confirmed by the ameliorating effect of piracetam and memantine drugs on diabetes mellitus. In addition, amyloid beta (especially Aβ40) can be utilized as biochemical marker of T2D in Alzheimer's patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their deep thanks to Sarah S. Al-Salem, a student in the College of Pharmacy, Qassim University, KSA, who helped with the collection of data and Marwa Sharadah who helped with the biostatistical analyses of the data. The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article

Authors’ contributions

Amira S Ahmed and Rehab M Elgharabawy: participated in all parts of the research.

Amal H AL-Najjar: participated in the collection of samples.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Barbagallo M, Dominguez LJ. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer’s disease. World J Diab 2014; 5: 889–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strachan MW, Reynolds RM, Marioni RE, Price JF. Cognitive function, dementia and type 2 diabetes mellitus in the elderly. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2011; 7: 108–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sunil KS, Ankita S, Ved P, Selvaa KC. Structure modeling and dynamics driven mutation and phosphorylation analysis of Beta-amyloid peptides. Bioinformation 2014; 10: 569–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jayaraman A, Pike CJ. Alzheimer’s disease and type 2 diabetes: multiple mechanisms contribute to interactions. Curr Diab Rep 2014; 14: 476–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim B, Feldman EL. Insulin resistance as a key link for the increased risk of cognitive impairment in the metabolic syndrome. Exp Mol Med 2015; 47: e149–e149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akter K, Lanza EA, Martin SA, Myronyuk N, Rua M, Raffa RB. Diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer's disease: shared pathology and treatment. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2011; 71: 365–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De La Monte SM. Contributions of brain insulin resistance and deficiency in amyloid-related neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Drugs 2012; 72: 49–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiaohua L, Dalin S, Sean XL. Link between type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease: from epidemiology to mechanism and treatment. Clin Interv Aging 2015; 10: 549–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson D, Pepys MB and Wood SP (Feb 1999). The physiological structure of human C-reactive protein and its complex with phosphocholine. Structure 1999;7:169–77. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Adam SS, Key NS, Greenberg CS. D-dimer antigen: current concepts and future prospects. Blood 2009; 113: 2878–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khosla T, Lowe CR. Indices of obesity derived from body weight and height. Br J Prev Soc Med 1967; 21: 122–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Temple RC, Clark PM, Hales CN. Measurement of insulin secretion in type 2 diabetes: problems and pitfalls. Diab Med 1992; 9: 503–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem 1972; 18: 499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galasko D. Biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease-clinical needs and application. J Alzheimers Dis 2005; 8: 339–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thakker DR, Weatherspoon MR, Harrison J, Keene TE, Lane DS, Kaemmerer WF, Stewart GR, Shafer LL. Intracerebroventricular amyloid-beta antibodies reduce cerebral amyloid angiopathy and associated micro-hemorrhages in aged Tg2576 mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2009; 106: 4501–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clearfield MB. C-reactive protein: a new risk assessment tool for cardiovascular disease. J Am Osteopath Assoc 2005; 105: 409–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franck PF, Steen G, Lombarts AJ, Souverijn JH, Van Wermeskerken RK. Multicenter harmonization of common enzyme results by fresh patient-pool sera. Clin Chem 1998; 44: 614–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang XQ, Ren YK, Chen RQ, Zhuang YY, Fang HR, Xu JH, Wang CY, Hu B. Formaldehyde induces neurotoxicity to PC12 cells involving inhibition of paraoxonase-1 expression and activity. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2011; 38: 208–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishank SS, Singh MP, Yadav R. Clinical impact of factor V Leiden, prothrombin G20210A, and MTHFR C677T mutations among sickle cell disease patients of Central India. Eur J Haematol 2013; 91: 462–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mann CK, Yoe JH. Spectrophotometric determination of magnesium with xylidyl blue. Anal Chem Acta 1957; 16: 155–60. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morris JK, Vidoni ED, Honea RA, Burns JM. Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative. Impaired glycemia increases disease progression in mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiol Aging 2014; 35: 585–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luchsinger JA, Gustafson DR. Adiposity, type 2 diabetes, and Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2009; 16: 693–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gustafson D, Rothenberg E, Blennow K, Steen B, Skoog I. An 18-year follow-up of overweight and risk of Alzheimer disease. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163: 1524–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Volpe CMO, Abreu LFM, Soares AN, Silva FDL, Chaves MM, Nogueira-Machado JA. High levels of HbA1c from T2DM patients positively correlated with increased of oxidative stress biomarker and IL-6 Levels. Endocrinol Diab Mellitus 2014; 2: 130–5. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prakash VR, Xiongwei Z, George P, Mark AS. Oxidative stress in diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimer’s Dis 2009; 16: 763–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramirez A, Wolfsgruber S, Lange C, Kaduszkiewicz H, Weyerer S, Werle J, et al. Elevated HbA1c is associated with increased risk of incident dementia in primary care patients. J Alzheimer’s Dis 2015; 44: 1203–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Regmi P, Gyawali P, Shrestha R, Sigdel M, Mehta KD, Majhi S. Pttern of dyslipidemia in Type-2 diabetic subjects in eastern Nepal. J Nepal Assoc Med Lab Sci 2009; 10: 11–3. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldberg IJ. Diabetic dyslipidemia: causes and consequences. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001; 86: 965–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dixit AK, Dey R, Suresh A, Chaudhuri S, Panda AK, Mitra A, Hazra J. The prevalence of dyslipidemia in patients with diabetes mellitus of ayurveda Hospital. J Diab Metab Disord 2014; 13: 58–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reitz C. Dyslipidemia and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2013; 15: 307–307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ojo O, Brooke J. Evaluating the association between diabetes, cognitive decline and dementia. J Environ Res Pub Health 2015; 12: 8281–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jolivalt CG, Lee CA, Beiswenger KK, Smith JL, Orlov M, Torrance MA, Masliah E. Defective insulin signaling pathway and increased glycogen synthase kinase-3 activity in the brain of diabetic mice: parallels with Alzheimer’s disease and correction by insulin. J Neurosci Res 2008; 86: 3265–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao L, Teter B, Morihara T, Lim GP, Ambegaokar SS, Ubeda OJ, Frautschy SA, Cole GM. Insulin-degrading enzyme as a downstream target of insulin receptor signaling cascade: implications for Alzheimer’s disease intervention. J Neurosci 2004; 24: 11120–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sato N, Morishita R. Plasma Aβ: a possible missing link between Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes. Diabetes 2013; 62: 1005–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Y, Zhou B, Zhang F, Wu J, Hu Y, Liu Y, Zhai Q. Amyloid-beta induces hepatic insulin re-sistance by activating JAK2/STAT3/SOCS-1 signaling pathway. Diabetes 2012; 61: 1434–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirano T, Ishihara K, Hibi M. Roles of STAT3 in mediating the cell growth, differentiation and survival signals relayed through the IL-6 family of cytokine receptors. Oncogene 2000; 19: 2548–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y, Zhou B, Deng B, Zhang F, Wu J, Wang Y, Le Y, Zhai Q. Amyloid-beta induces hepatic insulin resistance in vivo via JAK2. Diabetes 2013; 62: 1159–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mugabo Y, Li L, Renier G. The connection between C-reactive protein (CRP) and diabetic vasculopathy. Focus on preclinical findings. Curr Diab Rev 2010; 6: 27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yarchoan M, Louneva N, Xie SX, Swenson FJ, Hu W, Soares H, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM, Kling MA, Shaw LM, Chen-Plotkin A, Wolk DA, Arnold SE. Association of plasma C-reactive protein levels with diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Sci 2013; 333: 9–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eagan DE, Gonzales MM, Tarumi T, Tanaka H, Stautberg S, Haley AP. Elevated serum C-reactive protein relates to increased cerebral myoinositol levels in middle-aged adults. Cardiovasc Psychiatry Neurol 2012; 2012: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Azizi G, Navabi SS, Al-Shukaili A, Seyedzadeh MH, Yazdani R, Mirshafiey A. The role of inflammatory mediators in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J 2015; 15: e305–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gupta A, Iadecola C. Impaired Aβ clearance: a potential link between atherosclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci 2015; 7: 115–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hess K, Grant PJ. Inflammation and thrombosis in diabetes. Thromb Haemost 2011; 105: S43–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carcaillon L, Gaussem P, Ducimetière P, Giroud M, Ritchie K, Scarabin PY. Elevated plasma fibrin D-dimer as a risk factor for vascular dementia: the Three-City cohort study. J Throm Haemost 2009; 7: 1972–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Del Gobbo LC, Song Y, Poirier P, Dewailly E, Elin RJ, Egeland GM. Low serum magnesium concentrations are associated with a high prevalence of premature ventricular complexes in obese adults with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2012; 11: 23–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barbagallo M, Dominguez LJ. Magnesium and type 2 diabetes. World J Diab 2015; 6: 1152–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu ZP, Li L, Bao J, Wang ZH, Zeng J, Liu EJ, Li XG, Huang RX, Gao D, Li MZ, Zhang Y, Liu GP, Wang JZ. Magnesium protects cognitive functions and synaptic plasticity in streptozotocin-induced sporadic Alzheimer’s model. PLoS One 2014; 9: e108645–e108645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]