Abstract

Glycoproteins contain a wealth of valuable information regarding the development and disease status of cells. In cancer cells, some glycans (such as the Tn antigen) are highly up-regulated, but this remains largely unknown for glycoproteins with a particular glycan. Herein, an innovative method combining enzymatic and chemical reactions was first designed to enrich glycoproteins with the Tn antigen. Using synthetic glycopeptides with O-GalNAc (the Tn antigen) or O-GlcNAc, we demonstrated that the method is selective for glycopeptides with O-GalNAc and can distinguish between these two modifications. The diagnostic ions from the tagged O-GalNAc further confirmed the effectiveness of the method and confidence in the identification of glycopeptides with the Tn antigen by mass spectrometry. Using this method, we identified 96 glycoproteins with the Tn antigen in Jurkat cells. The method can be extensively applied in biological and biomedical research.

Keywords: glycoproteins, hydrazide chemistry, MS-based proteomics, specific identification, Tn antigen

Both sides of the story

Glycoproteins contain a wealth of valuable information regarding the disease status of cells. The Tn antigen is highly expressed in cancer cells, but glycoproteins bearing this important antigen remain unexplored. Furthermore, the Tn antigen is indistinguishable from O-GlcNAc by MS. A novel method integrating enzymatic and chemical reactions for specific identification of glycoproteins with the Tn antigen by LC-MS/MS was developed.

Protein glycosylation is essential for mammalian cell survival, and aberrant glycosylation is directly related to human diseases, including cancer.[1] Glycosylation is highly complex because glycans are very diverse[2] and bind to the side chains of multiple amino acid residues.[3] For glycoproteins, both proteins and glycans contain a wealth of valuable information regarding the development and disease status of cells.[4] Modern mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics is very powerful for the global analysis of protein modifications, including glycosylation.[5] Due to the heterogeneity of glycans, many studies focus on the glycosylation site identification without the glycan information[6] or on glycan analysis without the protein information.[7] Studies of proteins containing a particular glycan remain largely unexplored.

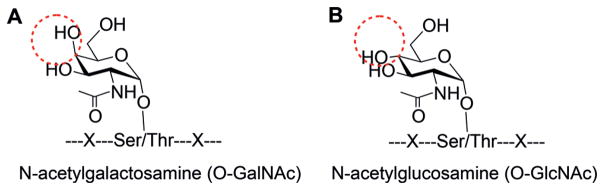

Subtle differences on glycans may result in entirely distinct functions of glycoproteins. For instance, proteins may be modified by N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc)[8] or N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc).[9] These two types of modifications are very similar, as shown in Scheme 1. First, both are bound to the S/T side chains. Second, the composition of the two glycans is identical; thus, they cannot be readily distinguished by MS. Although the subcellular location of glycoproteins is used to differentiate them, sometimes the result may not be reliable. For the two glycan structures, the only difference is the isomerism of the C4 hydroxy group.

Scheme 1.

The subtle difference between protein A) O-GalNAcylation and B) O-GlcNAcylation.

It is well-known that the functions of protein O-GlcNA-cylation and O-GalNAcylation are completely different. O-GlcNAcylation is regulated by O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT)[10] and O-GlcNAc amidase (OGA).[8] This modification is involved in cross-talk with phosphorylation, and thus many phosphoproteins located in the cytosol and nucleus may also be O-GlcNAcylated. Together with phosphorylation, O-GlcNAcylation regulates many cellular events, from signal transduction to gene expression.[8,11] In contrast, based on current understanding, O-GalNAcylation is a type of aberrant glycosylation; O-GalNAc is a truncated O-glycan correlated with tumor metastasis, and thus it is a tumor-associated antigen, termed the Tn antigen.[9,12] In addition to distinguishing it from O-GlcNAc, due to the clinical and biological importance of protein O-GalNAcylation, systematic identification of proteins with the Tn antigen is urgent. So far, the global identification of glycoproteins bearing the Tn antigen has yet to be reported due to the lack of an effective method.

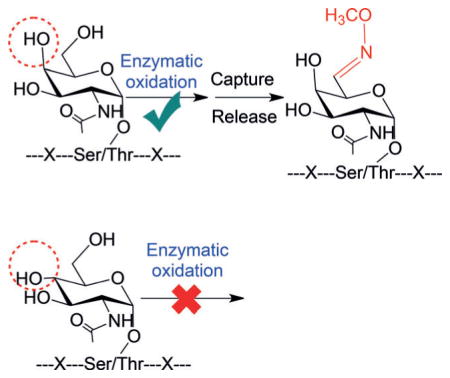

An innovative method combining enzymatic and chemical reactions was first designed to enrich glycoproteins with the Tn antigen, followed by MS analysis. O-GalNAc, but not O-GlcNAc, was selectively oxidized by galactose oxidase. The resulting aldehyde group enabled us to enrich glycopeptides with the Tn antigen through hydrazide beads. Enriched glycopeptides were released using methoxylamine (CH3ONH2) and tagged with a small group for MS analysis. This method was tested by using two types of synthetic glycopeptides with O-GlcNAc or O-GalNAc, and the results demonstrated high selectivity. The method was further optimized and applied for the global analysis of glycoproteins with the Tn antigen in Jurkat and MCF7 cells. Benefiting from the specificity of the enzymatic reaction, glycopeptides with the Tn antigen were enriched and tagged for MS analysis. Due to the diversity and complexity of protein glycosylation, effective methods are needed to advance our understanding of glycoprotein functions and lead to the discovery of glycoproteins as drug targets and disease biomarkers.

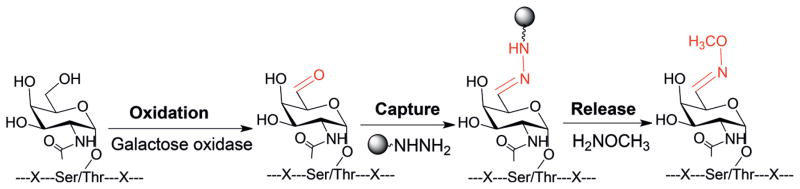

Glycans are highly diverse and informative.[4] To know which proteins are bound to a particular glycan, it is critical to selectively separate and enrich these glycoproteins in complexed biological samples prior to MS analysis. For glycoproteins with the Tn antigen, the separation method should also be able to distinguish glycopeptides with the Tn antigen or O-GlcNAc. Galactose oxidase has been extensively reported to oxidize glycolipids and glycoproteins in the literature.[13] Based on the specificity of the enzymatic reaction, our experimental design is shown in Figure 1. Galactose oxidase was employed to catalyze the oxidation of the Tn antigen on glycopeptides with strict regioselectivity, that is, only for GalNAc[14] but not GlcNAc.

Figure 1.

Specific enrichment of glycopeptides with the Tn antigen.

After the enzymatic reaction, the oxidized glycopeptides with the Tn antigen were enriched by hydrazide beads and released with methoxylamine for MS analysis. There are several advantages of using CH3ONH2 to release the enriched glycopeptides. First, CH3ONH2 can effectively release the enriched glycopeptides (Supporting Information, Figure S1). Second, after the release, a very small tag (+27 Da) is generated, which has no or minimal effect on the MS analysis of glycopeptides. Furthermore, O-GalNAc tagged with CH3ONH2 results in a unique mass tag to further distinguish O-GalNAc from O-GlcNAc or any other modified groups during the MS analysis.

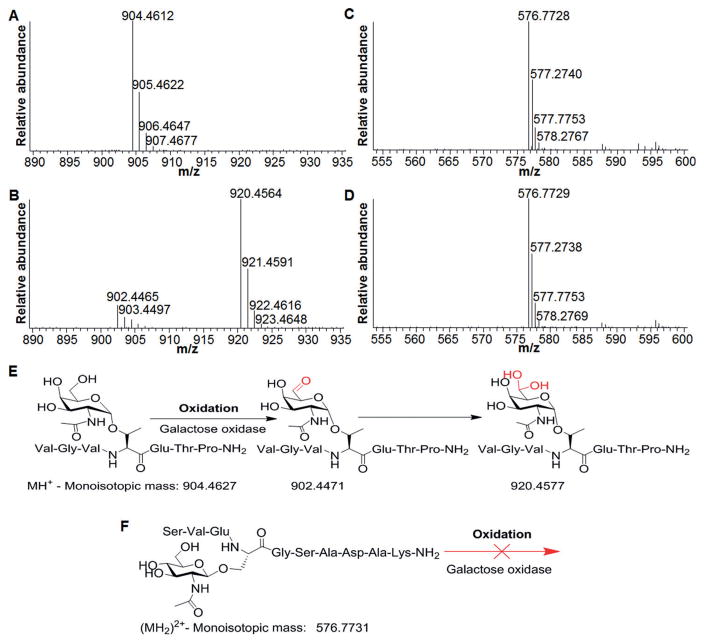

To test the effectiveness of the method, especially regarding the selectivity, two synthetic glycopeptides with O-GlcNAc or O-GalNAc were used. For the glycopeptide with O-GalNAc (VGVT(O-GalNAc)ETP-NH2), the dominant peak at m/z 904.4612 is from the singly charged glycopeptide (Figure 2A). After incubating the glycopeptide with galactose oxidase for 1 h, we were not able to find the same peak (Figure 2B), instead, two other peaks were detected around that area. The peak at 902.4465 corresponds to the oxidation and conversion of the hydroxy group to the aldehyde group (Figure 2E). In addition, the strongest peak at m/z 920.4564 is due to the species with the –C(OH)2 group formed from the aldehyde group in aqueous solution, as reported previously.[14] With high mass accuracy MS, all these masses match very well with the theoretical ones with less than a 2 ppm difference.

Figure 2.

Test results for the selectivity of the oxidation reaction with galactose oxidase using the synthetic glycopeptides with O-GalNAc or O-GlcNAc. A) Mass spectrum of the glycopeptide with the Tn antigen, and the structure in (E). B) MS after the oxidation reaction, and the reaction and the product structures in (E). C) MS of the glycopeptide with O-GlcNAc, and the structure in (F). D) MS after the oxidation reaction, the glycopeptide structure in (F). E) The oxidation reaction of the glycopeptide with the Tn antigen. F) The oxidation reaction of the glycopeptide with O-GlcNAc cannot happen.

For the glycopeptide with O-GlcNAc (SVES(O-GlcNAc)GSADAK-NH2), the peak at 576.7728 is from the doubly charged glycopeptide before the oxidation reaction (Figure 2C). After incubating with the oxidase (Figure 2D), the strongest peak is located at the same exact position, and we did not detect any new peaks. These results confirmed that the O-GlcNAc was not oxidized by the oxidase (Figure 2F).

By employing the synthetic glycopeptides with O-GlcNAc or O-GalNAc, the experimental results clearly demonstrated that the method is highly selective for glycopeptides with O-GalNAc but not O-GlcNAc. Selectivity is critical in analyzing glycopeptides with a particular glycan.

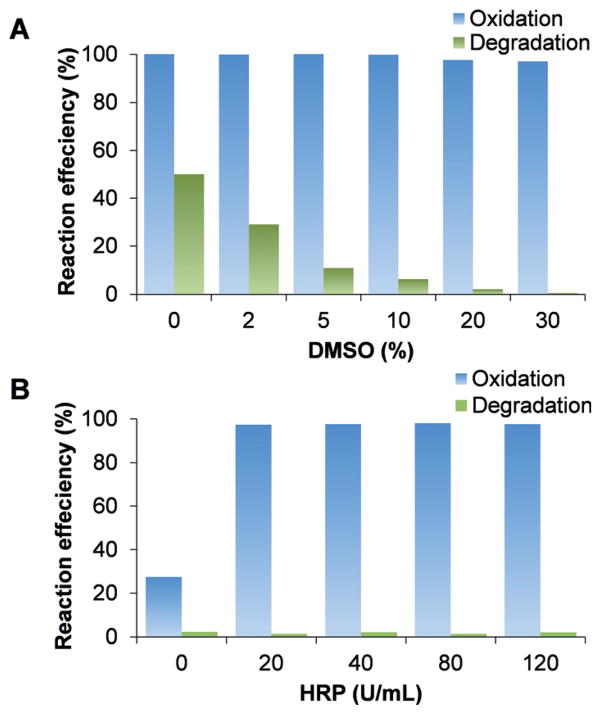

Experimental conditions were further optimized for this method. The glycopeptide dissociation was observed during the oxidation reaction, which may be due to the generation of radicals. Radicals can be scavenged by DMSO. Without DMSO, about half the glycopeptide was damaged (Figure 3A). The degradation rate was tested as a function of the DMSO concentration, and increasing the concentration continually decreased the degradation (Figure 3A). The degradation may be negligible with 10% DMSO. The addition of horseradish peroxidase (HRP)[13h,14] results in shifting the reaction towards completion. HRP can also keep the oxidase active by oxidizing the inactive form.[14] Without HRP, only circa 25% of the glycopeptide was oxidized. With HRP, the oxidation efficiencies were close to 100% (Figure 3B). A detailed description is in the Supporting Information.

Figure 3.

Optimization of the oxidation reaction. A) The effect of DMSO on the oxidation efficiency and glycopeptide degradation rate. B) Effect of HRP on the oxidation efficiency and glycopeptide damage.

Next, we applied this method for complex biological samples. Jurkat whole cell lysates were used to further test the effectiveness of the method because Jurkat cells have a defect in C1GALT1C (core 1 β3-galactosyltransferase specific molecular chaperone [Cosmc])[15] and therefore express the Tn antigen. Three biologically independent experiments were performed. The enriched glycopeptides were measured with LC-MS/MS, and both full MS and MS2 were recorded in the Orbitrap cell with high resolution and mass accuracy, which allowed us to confidently identify glycopeptides.

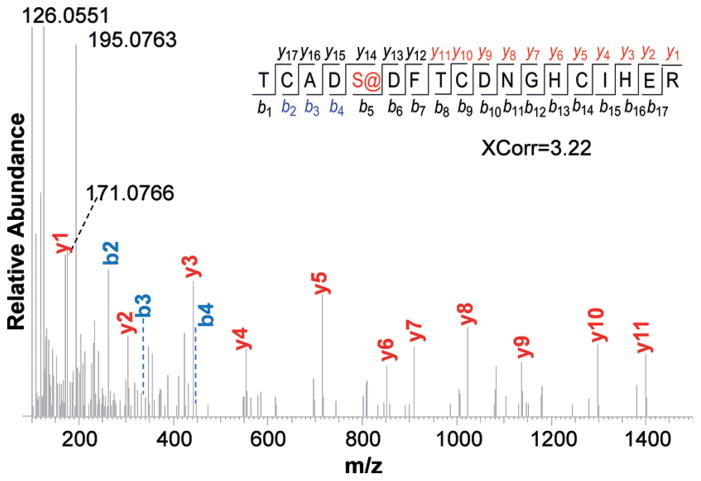

An example of the glycopeptides identified with the Tn antigen is in Figure 4. The glycopeptide TCADS@DFTCDNGHCIHER (@-glycosylation site) was confidently identified with an XCorr of 3.22. This peptide is from protein LRP8, which is a low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 8 located on the cell surface, and the identified site S89 is located outside of the cell. Another example of an identified glycopeptide is in the Supporting Information, Figure S2.

Figure 4.

An example of identified glycopeptide with the Tn antigen (TCADS@DFTCDNGHCIHER from LRP8).

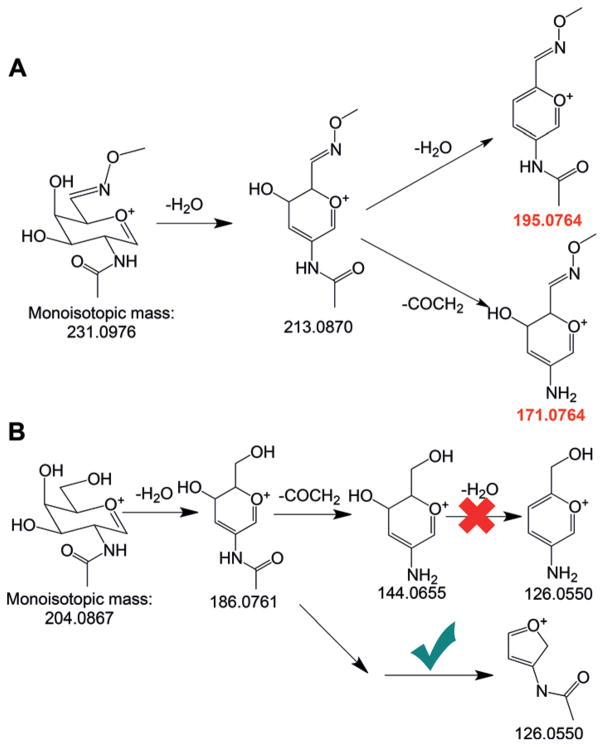

In MS2, nearly every major peak at m/z >400 was assigned to a fragment of the glycopeptide. However, several dominant peaks at m/z <400 cannot be assigned by SEQUEST[16] but are the diagnostic peaks from the glycan component. In this case, GalNAc was oxidized and tagged with CH3ONH2; thus, any fragments with the tag must have a mass shift of 27.0109 Da. The peaks at m/z 195.0763 and m/z 171.0766 are related to the common diagnostic peaks at m/z 168.0661 and m/z 144.0661 with a mass shift of 27.0109 Da. The dissociation pathways for the tagged GalNAc generating these two peaks are in Scheme 2A. The observed masses match excellently with the theoretical values. This clearly demonstrated that the new tag made O-GalNAc unique, and it can distinguish glycopeptides with the Tn antigen from those with O-GlcNAc or other modified groups.

Scheme 2.

Dissociation pathways for A) the tagged GalNAc or B) GalNAc.

The peak at m/z 126.0550 is a well-known diagnostic peak for sugars, including GalNAc, and there are different proposed dissociation pathways for this peak, as displayed in Scheme 2B.[17] The current result strongly suggested that the glycan dissociates through the unpopular bottom process in Scheme 2B. A detailed discussion is in Supporting Information.

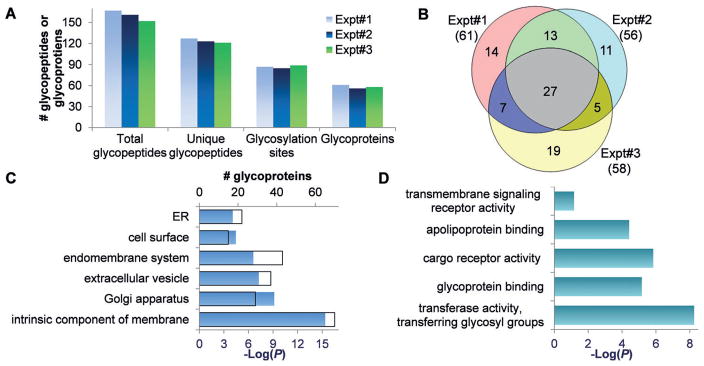

Among the three biologically independent experiments, the number of total glycopeptides, unique glycopeptides, glycoproteins, and glycosylation sites were all very consistent (Figure 5A). We identified 87 glycosylation sites on 61 proteins in the first experiment (Supporting Information, Table S1), 85 sites on 56 proteins in the second (Table S2), and 89 sites on 58 proteins in the third (Table S3). The overlap of the glycoproteins identified in three experiments is displayed in Figure 5B, and a total of 96 glycoproteins were found to bear the Tn antigen. To further demonstrate the effectiveness of the method, another type of cells (MCF7) was tested, and 45 O-GalNAcylation sites on 33 glycoproteins were confidently identified (Table S4). More glycoproteins with the Tn antigen were identified in Jurkat cells due to a defect of C1GALT1C.

Figure 5.

Results of identified glycopeptides with the Tn antigen in Jurkat cells. A) Comparison of total and unique glycopeptides, glycosylation sites and glycoproteins from three biologically independent experiments. B) Overlap of glycoproteins identified from the three experiments. C) Protein clustering based on cellular compartment. D) Protein clustering based on molecular function.

For 87 sites identified in the first experiment of Jurkat cells, 52 sites have a ModScore >13. Similar results were obtained for the other experiments. Compared to N-glycosylation analysis, the percentage of well-localized sites was relatively lower. The possible reasons are discussed in the Supporting Information.

The identified glycoproteins were clustered using the database for annotation, visualization and integrated discovery (DAVID).[18] Among 96 glycoproteins, the highest enriched category is “intrinsic component of membrane” with a P value of 4.2×0 10−16, and 73% of glycoproteins (70) belong to this category (Figure 5C). The second most enriched glycoproteins are those in the Golgi apparatus (29 proteins, P = 7.1×10−10). The enriched categories also include extracellular vesicle, endomembrane system, cell surface, and ER. These results further confirmed that the method is effective and that identified glycoproteins contain O-GalNAc, rather than O-GlcNAc because glycoproteins with O-GlcNAc are normally located in the cytosol and nucleus.

Molecular function analysis showed that glycoproteins related to the transferase activity (transferring glycosyl groups) are the most enriched (Figure 5D). In addition, glycoproteins with binding and receptor activities are also on the top enrichment list. Eleven glycoproteins have the transmembrane signaling receptor activity, which are normally located on the cell surface, and some sites of these glycoproteins are listed in the Supporting Information, Table S5. For example, protein PTPRC contained O-GalNAc at sites 137 and 140, which were identified in all three experiments. This protein (CD45) is a receptor-type tyrosine-protein phosphatase C and is required for T-cell activation through the antigen receptor. The two identified sites are located in the extracellular space, which may be involved in interactions with ligand or other molecules.

Glycoproteins often reflect the development and disease statuses of cells, and both their protein and glycan parts are highly informative. By integrating enzymatic and chemical reactions with MS-based proteomics, we developed a novel method targeting glycoproteins with a particular glycan, that is, the Tn antigen. Benefiting from the inherent specificity of the enzymatic reaction, this method demonstrated to be effective in identifying glycopeptides with the Tn antigen. In addition, this method can also be used to unambiguously distinguish glycopeptides with O-GalNAc from those with O-GlcNAc, as demonstrated in Figure 2. The current method can be extensively applied in biological and biomedical research. The systematic investigation of glycoproteins with a particular glycan will advance our understanding of glycoprotein and glycan functions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01GM118803), and the National Science Foundation (CAREER Award, CHE-1454501).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information for this article can be found under: https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201702191.

References

- 1.a) Gabius HJ, Andre S, Kaltner H, Siebert HC. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2002;1572:165–177. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00306-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Fuster MM, Esko JD. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:526–542. doi: 10.1038/nrc1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Gilgunn S, Conroy PJ, Saldova R, Rudd PM, O’Kennedy RJ. Nat Rev Urol. 2013;10:99– 107. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2012.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marino F, Bern M, Mommen GPM, Leney AC, van Gaansvan den Brink JAM, Bonvin A, Becker C, van Els C, Heck AJR. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:10922–10925. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b06586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spiro RG. Glycobiology. 2002;12:43R–56R. doi: 10.1093/glycob/12.4.43r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Hudak JE, Bertozzi CR. Chem Biol. 2014;21:16–37. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) An HJ, Kronewitter SR, de Leoz MLA, Lebrilla CB. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2009;13:601– 607. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Zhang H, Li XJ, Martin DB, Aebersold R. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:660–666. doi: 10.1038/nbt827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) An HJ, Peavy TR, Hedrick JL, Lebrilla CB. Anal Chem. 2003;75:5628–5637. doi: 10.1021/ac034414x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Wollscheid B, Bausch-Fluck D, Henderson C, O’Brien R, Bibel M, Schiess R, Aebersold R, Watts JD. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:378–386. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Zielinska DF, Gnad F, Wisniewski JR, Mann M. Cell. 2010;141:897–907. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Steentoft C, Vakhrushev SY, Vester-Christensen MB, Schjoldager K, Kong Y, Bennett EP, Mandel U, Wandall H, Levery SB, Clausen H. Nat Methods. 2011;8:977–982. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Chen WX, Smeekens JM, Wu RH. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13:1563–1572. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.036251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Reiding KR, Ederveen ALH, Rombouts Y, Wuhrer M. J Proteome Res. 2016;15:3489–3499. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.6b00071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Loziuk PL, Hecht ES, Muddiman DC. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2017;409:487–497. doi: 10.1007/s00216-016-9776-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Xiao HP, Wu RH. Chem Sci. 2017;8:268– 277. doi: 10.1039/c6sc01814a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao LW, Yu L, Guo ZM, Shen AJ, Guo YN, Liang XM. J Proteome Res. 2014;13:1485–1493. doi: 10.1021/pr401049e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schiel JE, Smith NJ, Phinney KW. J Mass Spectrom. 2013;48:533–538. doi: 10.1002/jms.3196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hart GW, Housley MP, Slawson C. Nature. 2007;446:1017–1022. doi: 10.1038/nature05815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ju TZ, Otto VI, Cummings RD. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:1770–1791;. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem. 2011;123:1808–1830. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lazarus MB, Nam YS, Jiang JY, Sliz P, Walker S. Nature. 2011;469:564–U168. doi: 10.1038/nature09638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Wang XS, Yuan ZF, Fan J, Karch KR, Ball LE, Denu JM, Garcia BA. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2016;15:2462–2475. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O115.049627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Khidekel N, Ficarro SB, Clark PM, Bryan MC, Swaney DL, Rexach JE, Sun YE, Coon JJ, Peters EC, Hsieh-Wilson LC. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:339– 348. doi: 10.1038/nchembio881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao Y, Merling A, Karsten U, Goletz S, Punzel M, Kraft R, Butschak G, Schwartz-Albiez R. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:89–99. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Morell AG, Van Den Hamer CJA, Scheinberg IH, Ashwell G. J Biol Chem. 1966;241:3745–3749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Suzuki Y, Suzuki K. J Lipid Res. 1972;13:687–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Gahmberg CG, Hakomori S-i. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:4311–4317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Gahmberg CG. Methods Enzymol. 1978;50:204–206. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(78)50020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Rannes JB, Ioannou A, Willies SC, Grogan G, Behrens C, Flitsch SL, Turner NJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:8436–8439. doi: 10.1021/ja2018477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Taga Y, Kusubata M, Ogawa-Goto K, Hattori S. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11:9. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.010397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Ramya TNC, Weerapana E, Cravatt BF, Paulson JC. Glycobiology. 2013;23:211–221. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cws144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Parikka K, Tenkanen M. Carbohydr Res. 2009;344:14– 20. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2008.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parikka K, Master E, Tenkanen M. J Mol Catal B. 2015;120:47–59. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ju TZ, Cummings RD. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16613–16618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262438199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eng JK, McCormack AL, Yates JR. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1994;5:976–989. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)80016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.a) Zhao P, Viner R, Teo CF, Boons GJ, Horn D, Wells L. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:4088–4104. doi: 10.1021/pr2002726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Halim A, Westerlind U, Pett C, Schorlemer M, Ruetschi U, Brinkmalm G, Sihlbom C, Lengqvist J, Larson G, Nilsson J. J Proteome Res. 2014;13:6024–6032. doi: 10.1021/pr500898r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Yu J, Schorlemer M, Toledo AG, Pett C, Sihlbom C, Larson G, Westerlind U, Nilsson J. Chem Eur J. 2016;22:1114– 1124. doi: 10.1002/chem.201503659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.