ABSTRACT

In yeast and mammals, selective vacuolar delivery and degradation of whole mitochondria, or mitophagy, represents an important quality control system and is achieved by a cargo recognition mechanism enabling selective elimination of dysfunctional mitochondria. As photosynthetic organelles that need light for energy production, plant chloroplasts accumulate sunlight-induced damage. Plants have evolved multiple mechanisms to avoid, relieve, or repair chloroplast photodamage. Our recent study showed that vacuolar degradation of entire chloroplasts, termed chlorophagy, is induced to degrade chloroplasts that are collapsed due to photodamage. Our results underscore the involvement of autophagy in the quality control of endosymbiotic, energy-converting organelles in eukaryotes.

KEYWORDS: Arabidopsis thaliana, autophagy, chlorophagy, chloroplasts, photodamage, plants, reactive oxygen species, ultraviolet-B

Macroautophagy/autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved process in eukaryotes leading to the degradation of cytoplasmic proteins and organelles, which facilitates the recycling of assimilated nutrients and the removal of unwanted cellular components. Heterotrophs produce most of the energy for growth via oxidative phosphorylation within mitochondria during respiration, which also results in the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the subsequent accumulation of mitochondrial damage. In yeast and mammals, dysfunctional mitochondria are eliminated via a selective process of autophagy termed mitophagy.

Our recent study indicates that photoautotrophic eukaryotes use an analogous selective autophagy mechanism for chloroplasts. Photosynthetic conversion of sunlight energy within chloroplasts is essential for growth in plants and algae; however, excess photo-energy damages chloroplasts. We found that Arabidopsis mutants lacking the core autophagy-related (ATG) genes, ATG5, ATG7 or ATG2, exhibit sensitivity to photodamage caused by ultraviolet-B (UVB) exposure. This result suggested that autophagy plays an important role in the plant response to UVB damage. To assess the role of autophagy in responses to UVB damage, we observed the behavior of leaf mesophyll cell chloroplasts via laser scanning confocal microscopy of plants expressing chloroplast stroma-targeted green fluorescent protein (GFP). Although all chloroplasts exhibiting chlorophyll autofluorescence had a GFP signal in the nontreated control plants, chloroplasts lacking a stroma-targeted GFP signal and appearing to move randomly were observed in the central area of cells in UVB-damaged plants. We confirmed the incorporation of such chloroplasts lacking stromal fluorescent protein into the vacuolar lumen using plants expressing vacuolar membrane-localized GFP along with stroma-targeted red fluorescent protein (RFP). Vacuolar accumulation of entire chloroplasts was also observed via transmission electron microscopy (TEM). This phenomenon was not observed in the autophagy-deficient mutants atg5 and atg7. Therefore, we concluded that vacuolar transport of entire chloroplasts by autophagy, termed chlorophagy, occurs in Arabidopsis photodamaged leaves (Fig. 1).

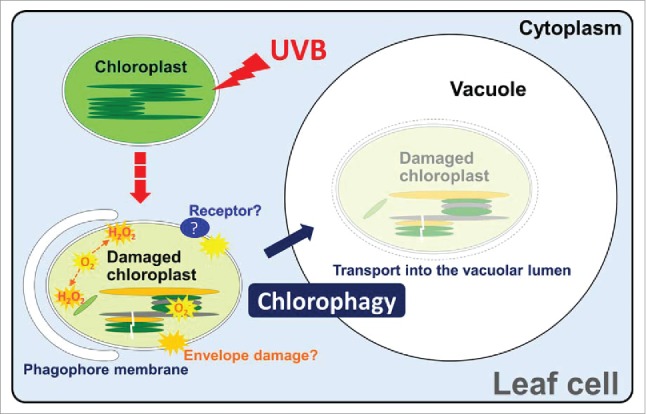

Figure 1.

A proposed model for ultraviolet-B (UVB)-damage induced chlorophagy. UVB exposure causes the accumulation of reactive oxygen species, including superoxide (O2−) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and damages chloroplasts. Damaged chloroplasts are transported into the vacuolar lumen for degradation via phagophore membrane-associated sequestering. The participation of unknown signal and receptor proteins enabling selective elimination of damaged chloroplasts is anticipated.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that mitophagy involves a highly controlled mechanism for recognition of autophagosomal cargo to selectively eliminate damaged mitochondria. In yeast, Atg32 accumulates on the outer membrane of oxidized mitochondria as a receptor protein that can interact with Atg8, which leads to sequestration by the phagophore, the precursor to the autophagosome. In mammalian cells, depolarized mitochondria are marked by PINK1 (PTEN induced putative kinase 1) to recruit the E3 ligase PARK2/Parkin leading to the ubiquitination of mitochondrial outer membrane proteins. The phagophore sequesters ubiquitinated mitochondria before transport to the lysosome for degradation. In Arabidopsis expressing GFP-ATG8a, we observed GFP-ATG8a-labeled tubular structures around individual chloroplasts after UVB exposure. Consistent with the observed induction of chlorophagy, chloroplast number per cell decreases in wild type but not in atg mutant plants after UVB exposure. TEM analysis showed cytosolic accumulation of collapsed chloroplasts exhibiting abnormal shape in UVB-damaged atg plants. These results support the notion that chlorophagy is also regulated in a selective manner to degrade photodamage-induced, abnormal chloroplasts (Fig. 1).

We investigated the involvement of ROS production in the induction of chlorophagy, and found that the presence of a scavenger of the ROS superoxide (O2−), suppresses UVB damage-induced chlorophagy. By contrast, the knockout mutation of a chloroplast O2− quenching enzyme, AT1G77490/thylakoidal ascorbate peroxidase, leads to the activation of UVB-induced chlorophagy. These results suggest that the accumulation of O2− or the subsequent chloroplast damage triggers the induction of chlorophagic elimination (Fig. 1). After UVB exposure, both the accumulation of hydrogen peroxide, a ROS resulting from the conversion of O2−, and cell death are enhanced in atg plants compared with wild type, which could underlie the UVB-sensitive phenotype of atg plants.

During PINK1-PARK2-mediated mitophagy in mammals, autophagy machinery in the cytoplasm recognizes defects in mitochondrial function via a modification on the outer envelope: the loss of transmembrane potential (TMP) driving ATP biosynthesis leads to PINK1 accumulation on the outer membrane because protein import into mitochondria also requires TMP. ROS accumulation might damage the envelope of chloroplasts; we observed aberrant chloroplasts with ruptured envelopes in UVB-damaged leaves. Therefore, it is conceivable that envelope damage due to ROS accumulation, or subsequent changes of the TMP across the envelope membranes, could induce chlorophagy (Fig. 1). However, several characteristics of the TMP are different between mitochondria and chloroplasts. Protein import into chloroplasts across the envelope does not require a TMP. Chloroplasts have a closed thylakoid membrane inside the double membrane of the envelope. In chloroplasts, ATP biosynthesis depends mainly on chemical potential (ΔpH) across the thylakoid membrane in contrast to mitochondrial ATP biosynthesis, which depends on electrical potential (ΔΨ) across the inner membrane of the envelope. Accordingly, it is likely that there is a chloroplast-specific mechanism for the recognition of collapsed chloroplasts.

Our recent study established the chlorophagy process that leads to the vacuolar digestion of entire photodamaged chloroplasts (Fig. 1). It is not yet clear whether chlorophagy is regulated as a process of selective autophagy or not. In contrast to the UVB-induced damage that accumulates in various macromolecules, visible light mainly damages the photosynthetic apparatus within chloroplasts as they absorb visible light for photosynthesis. We found that photodamage due to strong visible light also induces chlorophagy. Detailed analysis focusing on how visible light damage induces chlorophagy could help further our understanding of the selectivity of chlorophagy. Although recent studies demonstrated that oxidized peroxisomes and stressed endoplasmic reticulum are also targets for autophagy in Arabidopsis plants, receptor proteins for the selective removal of damaged organelles have not been identified. Elucidating the molecular basis of selectivity in plant organelle autophagy, including chlorophagy, is necessary for the further development in this field.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

This work was supported, in part, by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Numbers 17H05050 to M.I. and 16J03408 to S.N.), Building of Consortia for the Development of Human Resources in Science and Technology (to M.I.), and JST PRESTO (Grant Number JPMJPR16Q1 to M.I.).