Abstract

We previously constructed telomerase-dependent, replication-selective adenoviruses OBP-301 (Telomelysin) and OBP-401 (Telomelysin-GFP, TelomeScan), the replication of which is regulated by human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) promoter. By intratumoral injection (i.t.) these viruses could replicate within the primary tumor and subsequent lymph node metastasis. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the possibility of systemic administration of these telomerase-dependent adenoviruses. We assessed the antitumor efficacy of OBP-301 and the ability of OBP-401 to deliver GFP in hepatocellular carcinoma and metastatic colon cancer nude mouse models. We demonstrated that i.v. administration of OBP-301 significantly inhibited colon cancer liver metastases and orthotopically-implanted hepatocellular carcinoma. Further, we demonstrated that OBP-401 could visualize liver metastases by tumor-specific expression of the GFP gene after portal venous or i.v. administration. Thus, systemic administration of these adenoviral vectors should have clinical potential to treat and detect liver metastasis and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Keywords: Adenovirus, systemic injection, liver tumor, GFP

Introduction

Primary and metastatic liver tumors are a common cause of death throughout the world. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common primary liver tumor, is the fifth most common malignancy and the third most frequent cause of cancer death worldwide (1,2). HCC often metastasizes widely, and distant metastatic sites include lung, bone, adrenals, and brain. The 5-year survival rates of these patients are usually in the range of 16–25% (3). Colorectal cancer is also one of the most common tumors worldwide. The liver is the most preferential site for metastasis of colorectal cancer and over half of these patients die from their metastatic liver diseases (4). Therefore, management of the liver metastases is a key factor for colorectal cancer prognosis.

Liver resection is the only potentially curative treatment option available for patients with primary and metastatic liver tumors (5,6). However, since only a minority of patients with colorectal liver metastases or HCC are candidates for surgery (7–10), new therapeutic agents and innovative approaches for tumor detection are desired.

We previously constructed two conditionally-replicating type-5 adenoviruses, OBP-301 (Telomelysin) and OBP-401 (Telomelysin-GFP, TelomeScan). The replication of these viruses is regulated by the human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) promoter (11–15). hTERT is the catalytic subunit of telomerase which is highly active in cancer cells but quiescent in most normal somatic cells (16). Therefore, these adenoviruses have tumor-specific replication regulated by the hTERT transcriptional activity. OBP-301 has demonstrated a strong anticancer efficacy in a variety of tumors in vitro and in vivo (11,12,17–19). We also reported that OBP-401 can replicate in and label cancer cells with GFP in vitro and in vivo and thereby enables imaging of tumor cells by GFP fluorescence in vivo (15). Tumor specificity is conferred by selective replication of OBP-401 in the cancer cells. Replication of the virus, and therefore, production of GFP depends on the tumor-specific expression of telomerase. In those studies, however, the virus was administered locally such as by intratumoral injection or administration into a body cavity (thoracic or abdominal cavity). The efficacy of these viruses, when administered systemically, has not been evaluated.

In the present study, we examined the feasibility of systemic administration of OBP-301 and OBP-401 to colorectal liver metastases and to orthotopic HCC tumor in nude mice models, focusing on the antitumor efficacy of OBP-301 and the ability of OBP-401 to selectively induce GFP gene expression in cancer cells.

Materials and Methods

Recombinant Adenovirus

We previously constructed OBP-301, in which the hTERT promoter element drives the expression of the E1A and E1B genes linked with an IRES (11–14). OBP-401, containing the GFP gene under the control of the CMV promoter, was also previously constructed (15,20). These viruses were purified by ultracentrifugation in cesium chloride step gradients. Their titers were determined by a plaque-forming assay using 293 cells. The viruses were stored at −80°C.

Cell Culture

The human colorectal cancer cell line HCT-116 and the human hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines Hep3B and HepG2 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum.

GFP Gene Transduction of Cancer Cells

For GFP gene transduction of cancer cells, 20% confluent HCT-116 or Hep3B cells were incubated with a 1:1 precipitated mixture of retroviral supernatants of the PT67 GFP-expressing packaging cells and RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum for 72 hours. Fresh medium was replenished at this time. Tumor cells were harvested by trypsin/EDTA 72 h post-transduction and subcultured at a ratio of 1:15 into selective medium containing 200 μg/ml G418. The level of G418 was increased up to 800 μg/ml in a stepwise manner. GFP-expressing cancer cells were isolated with cloning cylinders (Bel-Art Products, Pequannock, NJ) using trypsin/EDTA and amplified by conventional culture methods in the absence of selective agent.

Animal Experiments

Athymic nude mice were kept in a barrier facility under HEPA filtration and fed with autoclaved laboratory rodent diet (Tecklad LM-485, Western Research Products, Orange, CA). All animal studies were conducted in accordance with the principles and procedures outlined in the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals under Assurance Number A3873-1. All animal procedures were performed under anesthesia using s.c. administration of a ketamine mixture (10 μl ketamine HCL, 7.6 μl xylazine, 2.4 μl acepromazine maleate, and 10 μl PBS).

Experimental Liver-Metastasis Model of Human Colon Cancer

To generate a liver metastasis model, unlabeled HCT-116 or HCT-116-GFP human colon cancer cells were injected at a density of 2.0 × 106 cells, in 50 μl of Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), into the spleen of nude mice through a 28-gauge needle at laparotomy.

Orthotopic Liver Tumor Model of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

An orthotopic liver tumor model with human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) was made with unlabeled Hep3B or Hep3B-GFP human hepatocelluler carcinoma cells. Unlabeled Hep3B or Hep3B-GFP cells (5.0 × 106 cells/10 μl Matrigel) were subserosally injected into the left lobe of the liver through a 28-gauge needle at laparotomy. Unlabeled HepG2 cells, cells (3.0 × 106 cells/50 μl Matrigel) were injected into the spleen of nude mice through a 28-gauge needle at laparotomy.

Antitumor Efficacy Studies

To assess the antitumor efficacy of i.v. administration of OBP-301 against liver metastases of the colorectal cancer, OBP-301 was injected once systemically into the tail vein at a dose of 5 × 108 PFU/100 μl five days after HCT-116-GFP cells were injected in the spleen. Control mice were injected with 100 μl PBS in an identical manner (n = 9 mice per group). Six weeks after tumor cell inoculation (i.e., five weeks after treatment), fluorescence imaging was performed using the Olympus OV100 Imaging System (Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan). GFP fluorescent intensity of the liver metastases and the number of lung metastases were determined. To obtain GFP intensity, exposure conditions were maintained constant at 30 msec to keep the data comparable. GFP intensity was quantified and presented in the units of SUM green intensity using CellR software (Olympus-Biosystems, Melville, NY). The experimental data are presented as mean ± SD. Comparison of the GFP intensity and the number of lung metastases between the treatment and control groups were analyzed using a two-tailed Student’s t test.

The antitumor efficacy of i.v. administration of OBP-301 was also assessed in an orthotopic liver tumor model of HCC. OBP-301 was i.v. injected biweekly (5.0 × 108 PFU/2 weeks for 6 weeks) starting from two weeks after Hep3B-GFP cells were injected into the liver. Control mice were injected with 100 μl PBS in an identical manner (n = 9 mice per group). All animals were examined eight weeks after cancer cell inoculation (i.e., two weeks after last treatment). Development of tumor growth and response to OBP-301 treatment were evaluated by the fluorescent area of the liver tumor calculated by CellR software using GFP images obtained with the Olympus OV100. The experimental data are presented as mean ± SD. Comparison of the tumor area between the treatment and control groups was analyzed using a two-tailed Student’s t test.

Viral GFP Labeling of Tumors

To assess the tumor detection ability of OBP-401 for metastatic liver tumors, a liver metastasis model of unlabeled HCT-116 cells was used. OBP-401 was injected intravenously or intrasplenically at a dose of 1 × 108 PFU/mouse. Animals were examined at laparotomy by fluorescence imaging with the OV100 five days after OBP-401 was administered. Some mice had a second-look observation a week after the first open examination.

To assess the tumor detection ability of OBP-401 in the orthotopic liver tumor model, unlabeled Hep3B cells were used. OBP-401 was injected systemically into the tail vein at a dose of 1 × 108 PFU/mouse two weeks after tumor cell inoculation. Animals were examined at laparotomy by fluorescence imaging with the OV100 five days after OBP-401 was administered. Some mice had a second-look observation four weeks after i.v. injection of OBP-401.

Fluorescence Optical Imaging and Processing

The Olympus OV100 Imaging System (Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan), containing an MT-20 light source was used. High-resolution images are captured directly on a PC (Fujitsu Siemens, Munich, Germany), and images are analyzed with the use of CellR software (Olympus-Biosystems, Melville, NY).

Results and Discussion

Liver metastasis model of human colon cancer

Intrasplenic inoculation of nude mice with unlabeled HCT-116 or HCT-116-GFP human colon cancer cells led to multiple experimental metastases in the liver within 14 days. With HCT-116-GFP, spleen tumors and lung metastasis could also be observed by fluorescence imaging at six weeks after cancer cell implantation.

Orthotopic liver tumor model of hepatocellular carcinoma

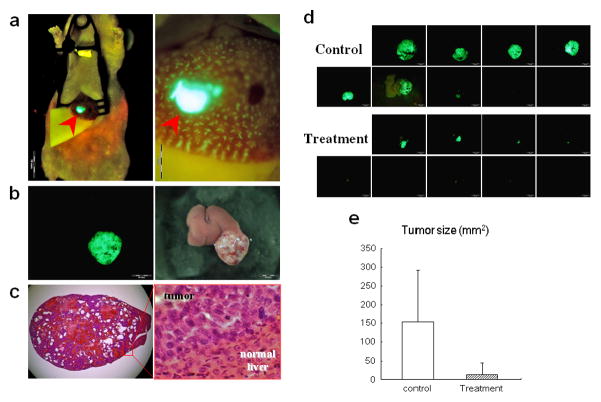

When unlabeled Hep3B or Hep3B-GFP human HCC cells were subserosally injected into the liver of nude mice (Fig. 1a), a small tumor mass (~2 mm) was often observed on the liver surface by two weeks after cancer cell inoculation. Hep3B liver tumors usually grew only in the injected lobe and rarely spread to other lobes (Fig. 1b). These tumors demonstrated abundant tumor blood vessels, indicating a rich blood supply for the tumor, which reflects HCC in human patients (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1. Efficacy of systemic OBP-301 administration on orthotopic HCC.

(a) Hep3B-GFP cells were subserosally injected into the left lobe of the liver to generate an orthotopic liver tumor model (left panel). Some cells could be seen accumulating in the terminal portal veins near the bleb of the injected site (right panel).

(b) Macroscopic appearance of Hep3B-GFP liver tumor 8 weeks after inoculation. Left, fluorescence detection; right, bright field observation.

(c) H&E staining of Hep3B-GFP liver tumor section. Left, × 10 magnification; right, detail of the boxed region. × 400 magnification.

(d) Macroscopic appearance of liver. Livers were excised 8 weeks after Hep3B-GFP cells injection. OBP-301 or PBS were i.v. injected biweekly starting from 2 weeks after tumor cell inoculation. Excised livers were photographed under fluorescence.

(e) Quantitative analysis of the tumor size (fluorescent area) of control and OBP-301 treated mice (P=0.00781).

Unlabeled HepG2 cells were also inoculated to the spleen of nude mice with the same technique used in the experimental colorectal liver metastasis model. Two weeks after tumor cell inoculation, multiple HepG2 tumors were observed on the liver surface.

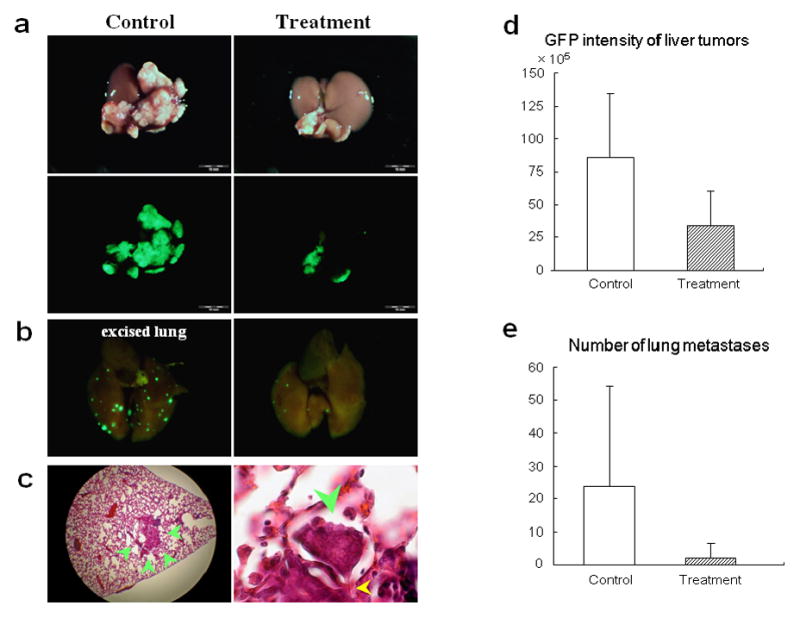

Inhibition of experimental colon-cancer metastasis by OBP-301

OBP-301 was i.v. injected at a dose of 5 × 108 PFU/mouse five days after HCT-116-GFP inoculation in the spleen. At six weeks after HCT-116-GFP colon cancer cell inoculation, 100% of the control animals developed liver tumors, and tumors in the spleen developed in 40% of control animals. Treatment with OBP-301 caused a significant inhibition in liver metastasis growth (p = 0.01431) (Fig. 2a,d). Additionally, OBP-301-treated animals showed a reduced number of lung metastases colonies compared to controls (p = 0.04951) (Fig. 2b,e). These results demonstrate that systemic dosing of OBP-301 has significant antitumor activity against experimental colon-cancer liver metastasis. In contrast to the experimental liver metastasis, OBP-301 did not have an apparent effect on the spleen tumors. The lack of effect of OBP-301 on the spleen tumors may be because of their very small size which made differences difficult to discern.

Figure 2. Systemic OBP-301 therapy of colon cancer liver metastases.

(a) Macroscopic appearance of livers. HCT-116-GFP cells were injected into the spleen of nude mice, and the liver was excised 6 weeks later. OBP-301 or PBS were i.v. injected 5 days after tumor cell inoculation. Excised livers were photographed under bright light (top panels). Fluorescence imaging demonstrated GFP expression signals on the HCT-116-GFP liver metastasis (bottom panels).

(b) Macroscopic appearance of lungs. Lung metastatic foci were detected with GFP fluorescence. Left, control; right, OBP-301 treatment significantly suppressed lung metastasis.

(c) H&E staining of lung metastasis in control mouse. Left, × 40 magnification; right, protrusion of tumor (green arrowhead) into the adjacent alveoli through the Kohn’s pore (yellow arrowhead). × 400 magnification.

(d) Quantitative analysis of the total GFP intensity in the liver of control and OBP-301 treated mice (P=0.01431).

(e) Quantitative analysis of the number of lung metastases of control and OBP-301 treated mice (P=0.04951).

Inhibition of orthotopic HCC by OBP-301

To evaluate the antitumor efficacy of OBP-301 on HCC tumors, the orthotopic liver tumor model of Hep3B-GFP was used.

The colorectal liver metastasis model was made by delivering cells into the portal vein as described above, while the orthotopic HCC model was made by injecting cells directly into the hepatic parenchyma, where at the early stage of tumor development most cells were thought to locate outside of the blood vessels. Thus, i.v. injected OBP-301 could target cancer cells more effectively in the colorectal liver metastasis model than in the HCC model. In the HCC model, therefore, we increased the number of injections of OBP-301 which was administered biweekly (5 × 108 PFU/2 weeks, i.v., for 6 weeks) starting two weeks after tumor cell inoculation. Treatment of OBP-301 caused a significant inhibition in liver tumor growth (p = 0.00781) (Fig. 3d,e). These results demonstrate that systemic dosing of OBP-301 has significant antitumor activity against Hep3B-GFP human HCC tumors.

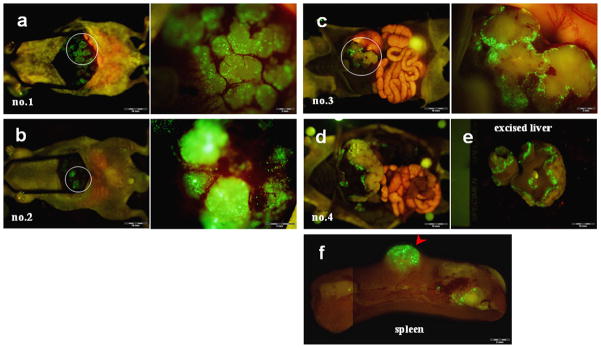

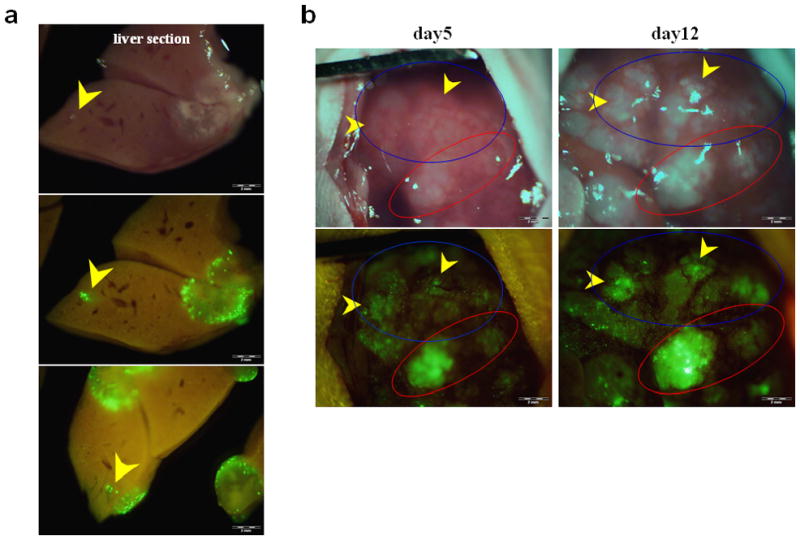

Figure 3. Portal venous delivery of OBP-401 selectively labeled multiple colon cancer liver metastases.

(a) Gross appearance of the abdominal cavity (mouse no.1). Five days after splenic injection of OBP-401, HCT-116 liver metastases were visualized by GFP fluorescence.

(b) Higher magnification of the liver surface indicated by the white circle in (a).

(c) Liver metastases were visualized by GFP fluorescence in mouse no.2.

Selective visualization of colorectal liver metastases by OBP-401 delivery of the GFP gene

To assess the tumor detection ability of OBP-401 for colorectal liver metastases, OBP-401 was administrated to mice by portal venous delivery or systemic delivery using the tail vein.

Animals with HCT-116 experimental liver metastases were intrasplenically injected with OBP-401 (1 × 108 PFU/mouse) 12 days after tumor cell inoculation. The spleen was used to access the portal venous circulation. Five days after injection of OBP-401, the liver metastases could be visualized by GFP fluorescence. Representative mice are shown in Figure 3. Cross-sections of the liver showed that GFP fluorescence occurred mainly at the periphery of the metastatic liver nodules (data not shown). Liver metastases in mice given 1 × 107 PFU of OBP-401 were not visualized efficiently by GFP expression (data not shown), indicating dose-response.

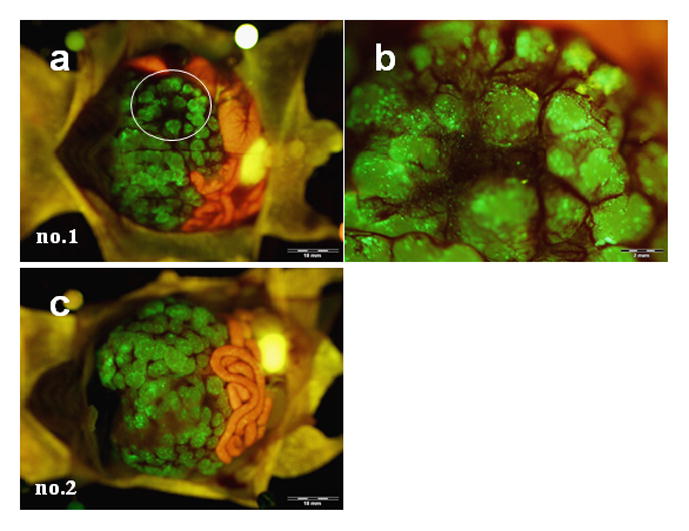

HCT-116 liver metastases could also be visualized by GFP fluorescence after i.v. injection of OBP-401 (1 × 108 PFU/mouse) (Fig. 4). Cross-sections of the liver also showed tiny metastatic foci visualized by GFP fluorescence (Fig. 5a). Moreover, a second-look observation performed a week after the first laparotomy showed that early metastatic liver tumors, not otherwise clearly visible under blight light, had been visualized with GFP fluorescence after i.v. injection of OBP-401 at as early as day 5, indicating the possibility of early detection of metastatic disease (Fig. 5b). When injected with more than 2 × 108 PFU of OBP-401, mice often showed GFP fluorescence in normal tissues such as liver, lung, spleen and thoracic duct (data not shown). Theses results suggest that colorectal liver metastases can be visualized by GFP fluorescence both by portal-venous and i.v. administration of OBP-401.

Figure 4. Selective GFP labeling of multiple liver metastases of human colon cancer by i.v. injection of OBP-401.

(a–c) Five days after i.v. injection with OBP-401, HCT-116 liver metastases were visualized by GFP fluorescence (mouse no.1–3, left). Higher magnification of the liver metastasis indicated by the white circle (right).

(d) Gross appearance of the abdominal cavity (mouse no.4).

(e) Macroscopic appearance of excised liver in mouse no.4. The margin of the liver metastasis was visualized by GFP fluorescence.

(f) Macroscopic appearance of spleen. Tumor development in the spleen was also visualized by GFP fluorescence 5 days after OBP-401 treatment.

Figure 5. Early metastatic liver tumors not otherwise clearly visible could be visualized after i.v. injection of OBP-401.

(a) Cross-sections of liver. GFP expression was mainly located at the periphery of the liver metastases. Tiny metastatic foci not otherwise clearly visible were visualized by GFP fluorescence after i.v. injection of OBP-401 (yellow arrow).

(b) Five days after i.v. injection of OBP-401, HCT-116 liver metastases were visualized by GFP fluorescence (indicated by red circle). There were areas in the liver which had GFP expression but seemed to be tumor free in bright light (blue circle). Seven days later, metastases could be visualized by bright light as well as GFP fluorescence (yellow arrows) demonstrating the power of OBP-401 to label very early, otherwise invisible metastases with GFP.

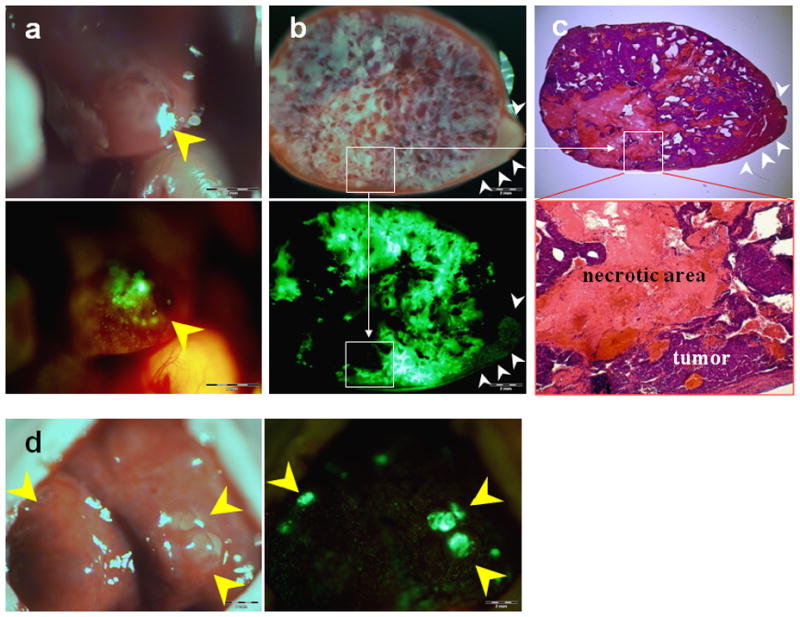

Selective visualization of orthotopic HCC by OBP-401

Five days after injection of OBP-401 (1 × 108 PFU/mouse) into the tail vein, liver tumors were visualized by GFP fluorescence (Fig. 6a). Cross-sections of the liver at four weeks after i.v. injection of OBP-401 showed that GFP expression was in the cancer cells and not in normal cells (Fig. 6b,c). Small liver tumor nodules were also visualized by GFP fluorescence after i.v. OBP-401 administration (Fig. 6a,d). Thus, we demonstrated that HCC liver tumors could be selectively visualized by GFP fluorescence after i.v. injection of OBP-401.

Figure 6. Selective visualization of orthotopic HCC tumors by i.v. injection of OBP-401.

(a) Five days after systemic administration of OBP-401, orthotopic Hep3B HCC was visualized by GFP fluorescence (yellow arrow). Top, bright field observation; bottom, fluorescence detection.

(b) Cross-section of liver 4 weeks after i.v. injection of OBP-401. GFP expression was selectively detected in the tumor. Top, bright field observation; bottom, fluorescence detection.

(c) H&E section of Hep3B liver tumor of (b). Top, × 10 magnification; bottom, detail of the boxed region. × 40 magnification.

Boxes refer to corresponding regions in b and c with high magnification in the lower panels of b and c.

(d) Orthotopic HepG2 HCC tumors (yellow arrows) were visualized by GFP fluorescence (yellow arrows) 4 weeks after i.v. injection of OBP-401.

Many studies have demonstrated that the majority of malignant human tumors tested express human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT). OBP-301 and OBP-401 specifically replicate in tumors due to hTERT expression in tumors (11,12,17–19). In previous studies, OBP-301 and OBP-401 were administered locally, such as by inratumoral or intrapleural administration. The present report demonstrates the systemic efficacy of OBP-301 and OBP-401 to selectively replicate and kill and label primary and metastatic liver tumors after i.v. administration. Closely related virus constructs will be compared to OBP-301 and -401 in the future.

Our laboratory pioneered the use of fluorescent proteins to visualize cancer cells in vivo. Cancer cells genetically labeled by fluorescent proteins have increased the possibility and sensitivity to observe progression of cancer cells in live animals (21). To evaluate antitumor efficacy of i.v. administration of OBP-301 against primary and metastatic tumors, we used GFP-expressing human cancer cell lines. We showed that i.v. administration of OBP-301 resulted in a significant reduction in experimental liver and pulmonary metastases in a colorectal liver metastases model, and effectively inhibited tumor formation and growth in an orthotopic HCC model. OBP-401 has less but still significant cytotoxic effects compared with OBP-301 (22). In fact, a significant inhibition of tumor growth by i.t. injection of OBP-401 was confirmed in vivo in our previous study (15, 20). However, OBP-401 at the tumor-selective labeling dose used in this i.v. injection study could not inhibit tumor growth effectively.

The imaging strategy using OBP-401 has a potential of being available in humans as a navigation system in the surgical treatment of malignancy. During surgery, tumors, which would be difficult to detect by direct visual detection, could be positively identified with GFP fluorescence using a hand held excitation light and appropriate filter goggles as we have previously shown in mice (23). Employment of a fluorescence surgical microscope would enable to see the GFP-expressing microscopic leading edge of the tumor and allow accurate resection with sufficient margins.

As for toxicity of OBP-301 and OBP-401, only when injected with 5 × 108 PFU OBP-301 for the first time, a few mice showed lethargy but fully recovered within an hour. None of the mice treated with OBP-301 or OBP-401 at the doses used in this study showed significant adverse effects during the observation period or histopathological changes in the liver at the time of sacrifice. In the near future the safety of OBP-301 will be confirmed in a Phase-I clinical trial which is currently underway.

Our studies suggest the clinical potential of OBP-301 and OBP-401.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute grant CA132242.

References

- 1.Bruix J, Hessheimer AJ, Forner A, Boix L, Vilana R, Llovet JM. New aspects of diagnosis and therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 2006;25:3848–56. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okuda K. Hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2000;32(1 Suppl):225–37. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80428-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takayasu K, Muramatsu Y, Moriyama N, et al. Clinical and radiologic assessments of the results of hepatectomy for small hepatocellular carcinoma and therapeutic arterial embolization for postoperative recurrence. Cancer. 1989;64:1848–52. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19891101)64:9<1848::aid-cncr2820640916>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koshariya M, Jagad RB, Kawamoto J, et al. An update and our experience with metastatic liver disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:2232–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kavolius J, Fong Y, Blumgart LH. Surgical resection of metastatic liver tumors. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 1996;5:337–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chouillard E, Cherqui D, Tayar C, Brunetti F, Fagniez PL. Anatomical bi- and trisegmentectomies as alternatives to extensive liver resections. Ann Surg. 2003;238:29–34. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000075058.37052.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiao LR, Hansen PD, Havlik R, Mitry RR, Pignatelli M, Habib N. Clinical short-term results of radiofrequency ablation in primary and secondary liver tumors. Am J Surg. 1999;177:303–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)00043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khatri VP, Petrelli NJ, Belghiti J. Extending the frontiers of surgical therapy for hepatic colorectal metastases: is there a limit? J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8490–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.6155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adam R. Chemotherapy and surgery: new perspectives on the treatment of unresectable liver metastases. Ann Oncol. 2003;14(Suppl 2):ii13–6. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdg731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bismuth H, Adam R, Lévi F, et al. Resection of nonresectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Surg. 1996;224:509–20. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199610000-00009. discussion 520–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawashima T, Kagawa S, Kobayashi N, et al. Telomerase-specific replication-selective virotherapy for human cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:285–92. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-1075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taki M, Kagawa S, Nishizaki M, et al. Enhanced oncolysis by a tropism-modified telomerase-specific replication-selective adenoviral agent OBP-405 (‘Telomelysin-RGD’) Oncogene. 2005;24:3130–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Umeoka T, Kawashima T, Kagawa S, et al. Visualization of intrathoracically disseminated solid tumors in mice with optical imaging by telomerase-specific amplification of a transferred green fluorescent protein gene. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6259–65. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hashimoto Y, Watanabe Y, Shirakiya Y, et al. Establishment of biological and pharmacokinetic assays of telomerase-specific replication-selective adenovirus. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:385–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00665.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kishimoto H, Kojima T, Watanabe Y, et al. In vivo imaging of lymph node metastasis with telomerase-specific replication-selective adenovirus. Nat Med. 2006;12:1213–9. doi: 10.1038/nm1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takakura M, Kyo S, Kanaya T, et al. Cloning of human telomerase catalytic subunit (hTERT) gene promoter and identification of proximal core promoter sequences essential for transcriptional activation in immortalized and cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1999;59:551–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watanabe T, Hioki M, Fujiwara T, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitor FR901228 enhances the antitumor effect of telomerase-specific replication-selective adenoviral agent OBP-301 in human lung cancer cells. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:256–65. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hioki M, Kagawa S, Fujiwara T, et al. Combination of oncolytic adenovirotherapy and Bax gene therapy in human cancer xenografted models. Potential merits and hurdles for combination therapy. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:2628–33. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang P, Watanabe M, Kaku H, et al. Direct and distant antitumor effects of a telomerase-selective oncolytic adenoviral agent, OBP-301, in a mouse prostate cancer model. Cancer Gene Ther. 2008;15:315–22. doi: 10.1038/cgt.2008.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujiwara T, Kagawa S, Kishimoto H, et al. Enhanced antitumor efficacy of telomerase-selective oncolytic adenoviral agent OBP-401 with docetaxel: preclinical evaluation of chemovirotherapy. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:432–40. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffman RM. The multiple uses of fluorescent proteins to visualize cancer in vivo. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:796–806. doi: 10.1038/nrc1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kyo S, Takakura M, Fujiwara T, Inoue M. Understanding and exploiting hTERT promoter regulation for diagnosis and treatment of human cancers. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:1528–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00878.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang M, Luiken G, Baranov E, Hoffman RM. Facile whole-body imaging of internal fluorescent tumors in mice with an LED flashlight. BioTechniques. 2005;39:170–2. doi: 10.2144/05392BM02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]