Abstract

Mammals share common strategies for regulating reproduction, including a conserved hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis yet individual species exhibit differences in reproductive performance. In this report, we describe the discovery of a species-restricted homeostatic control system programming testis growth and function. Prl3c1 is a member of the prolactin gene family and its protein product (PLP-J) was discovered as a uterine cytokine contributing to the establishment of pregnancy. We utilized mouse mutagenesis of Prl3c1 and revealed its involvement in the regulation of the male reproductive axis. The Prl3c1 null male reproductive phenotype was characterized by testiculomegaly and hyperandrogenism. The larger testes in the Prl3c1 null mice were associated with an expansion of the Leydig cell compartment. Prl3c1 locus is a template for two transcripts (Prl3c1-v1 and Prl3c1-v2) expressed in a tissue specific pattern. Prl3c1-v1 is expressed in uterine decidua, while Prl3c1-v2 is expressed in Leydig cells of the testis. 5′RACE, chromatin immunoprecipitation, and DNA methylation analyses were used to define cell-specific promoter usage and alternative transcript expression. We examined the Prl3c1 locus in five murid rodents and showed that the testicular transcript and encoded protein are the result of a recent retrotransposition event at the Mus musculus Prl3c1 locus. Prl3c1-v1 encodes PLP-J V1 and Prl3c1-v2 encodes PLP-J V2. Each protein exhibits distinct intracellular targeting and actions. PLP-J V2 possesses Leydig cell static actions consistent with the Prl3c1 null testicular phenotype. Analysis of the biology of the Prl3c1 gene has provided insight into a previously unappreciated homeostatic setpoint control system programming testicular growth and function.

Keywords: Testis, Leydig cells, prolactin family, transposable elements

Introduction

The process of reproduction has elements of regulation that are well conserved among diverse mammalian species (Achermann and Jameson 1999; Matzuk and Lamb 2008). This is best illustrated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis and the hormones used as messengers to control fertility (Achermann and Jameson 1999; Matzuk and Lamb 2008). Interestingly, reproductive function is also characterized by features that are seemingly unique to a species. These unique features represent a broad spectrum of biological processes associated with reproduction, including the regulation of gonadal size and function, gamete characteristics, the onset of puberty, sexual behavior, pregnancy, fecundity, as well as many others (Bronson 1989). Physiological impacts of these species-specific traits can be robust and have profound effects on reproductive fitness. Thus, on a backbone of a highly conserved reproductive axis there are prominent differences in reproductive performance among species.

The testis is regulated by a conserved homeostatic pathway involving the hypothalamus and pituitary (Desjardins 1978; Hedger and de Kretser 2000); yet exhibits striking species-specific characteristics (Fawcett et al. 1973; Kenagy and Trombulak 1986; Short 1997). Within the conserved regulatory pathway, the hypothalamus and pituitary produce gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) and gonadotropins (luteinizing hormone, LH; follicle stimulating hormone, FSH), respectively. GnRH regulates gonadotropin biosynthesis and secretion while LH and FSH act to regulate the growth and function of the testis (Hedger and de Kretser 2000; Matzuk and Lamb 2008). LH drives Leydig cell production of testosterone (Hedger and de Kretser 2000), which acts on an array of downstream targets to promote function of the entire male reproductive axis, including stimulating spermatogenesis, sperm maturation and transport, and male sexual and social behaviors (Desjardins 1978). FSH acts together with testosterone to promote sperm production (McLachlan et al. 1996; Matzuk and Lamb 2008). Homeostasis is achieved through a negative feedback system of testicular hormone action at the hypothalamus and pituitary to modulate the output of GnRH and gonadotropins, respectively (Amory and Bremner 2001; Tilbrook and Clarke 2001). These conserved elements of the male reproductive regulatory pathway have been effectively modeled in the mouse (Matzuk and Lamb 2008) but do not account for the species diversity in testicular size and function in mammals (Kenagy and Trombulak 1986; Short 1997; Montoto et al. 2011, 2012). In some mammals, the size of the testis can represent as much as 8 percent of body mass, whereas in other mammals the testis contributes to less than 0.1 percent of body mass (Kenagy and Trombulak 1986; e.g. Gerbilliscus afra, 8.4%; Mesocricetus auratus, 2.9%; Ovis aries, 0.9%; Mus musculus, 0.8%; Macaca mulatta, 0.7%; Bos taurus, 0.1%; Homo sapiens, 0.08%). Testis size correlates with contributions of Leydig cell and spermatogenic compartments and with their capacity to produce testosterone and sperm, respectively (Short 1997; Simmons and Fitzpatrick 2012; Birkhead 2000). Considerable species differences exist in sperm production. It has been proposed that sperm production relates to the mating system used by a species (monogamy versus polygyny versus polyandry), where sperm production and competition directly impact reproductive success (Short 1997; Simmons and Fitzpatrick 2012; Birkhead 2000). These extraordinary species differences in testis growth and function necessitate species-specific mechanisms modulating the function of the male reproductive axis. The origins of these species-specific reproductive traits are not yet fully appreciated.

In this report, we present the discovery of a rapidly evolving homeostatic control system contributing to the regulation of testis size and function in the mouse and provide insights into a mechanism employed to achieve species-specific reproductive traits.

Materials and Methods

Animals and tissue collection

C57BL/6 mice and testes from M. spretus, M. caroli and M. pahari were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). Testicular RNA samples from C57BL/6, 129S1/Svlmj, AKR/J, BALB/cByJ, BTBRT + tf/J, C3H/HeJ, CAST/EiJ, DBA/2J, FVB/NJ, KK/HIJ, NOD/LtJ, NZW/LacJ, PWD/PhJ, WSB/EiJ, and SJL/J mouse strains were obtained from Dr. Curtis Klaassen (University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS). CD-1 mice and Brown Norway (BN) rats were purchased from Charles River Laboratories International (Wilmington, MA). Fischer 344 (F344) and Holtzman Sprague Dawley (HSD) rats were obtained from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN). Animals were housed in an environmentally controlled facility with lights on from 0600 to 2000 h and were allowed free access to food and water. Timed pregnancies were generated by cohabitation of male and female mice. The presence of a seminal plug in the vagina was designated day 0.5 of gestation. Tissues for histological analysis were frozen in dry ice-cooled heptane and stored at −80°C until processing. Tissue samples for RNA or protein extraction were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until processing. Male mice were individually housed for two weeks prior to the collection of blood samples from the orbital sinus under isoflurane anesthesia.

Prl3c1 mutant mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells were produced by the NIH Knock-Out Mouse Project (KOMP) and obtained from the KOMP Repository (www.komp.org; VG10539). The University of Kansas Medical Center Transgenic and Gene-targeting Facility (Kansas City, KS) injected the mutant ES cells into C57BL/6 blastocysts. Germline competent chimeras were generated on C57BL/6 background and the mutation was subsequently moved to a mixed background of C57BL/6 X CD-1. Genotyping was routinely performed on genomic DNA isolated from tail biopsies using PCR with forward primers specific for the wild type allele (5′ CAGGGAATTCTTTGATTTGC 3′) and mutant allele (5′GCAATTGGACCGTTTGATCT 3′) and a common reverse primer (5′ ATCTGAGTTGCTGGCTTGGT 3′). Amplicons generated by the PCR reactions for the wild type and mutant alleles were 798 and 471 bp, respectively. All null mutant animals were generated on the mixed background using heterozygous × heterozygous breeding and wild type and null littermates were used in the experiments.

All experimentation with animals was performed in accordance with guidelines recommended by the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD). The University of Kansas Animal Care and Use Committee approved protocols for the care and use of animals.

Fertility tests

Beginning at 2–2.5 months of age, male and female mice were cohabited. Mutant and wild type males were housed with multiple wild-type females; whereas, mutant and wild type females were paired with fertile wild type males. The presence of seminal plugs in the vagina were examined daily. Seminal plug positive females were sacrificed on day 9.5 of pregnancy and the number of viable conceptuses counted.

Serum hormone measurements

Serum testosterone and LH levels were measured by radioimmunoassay at the University of Virginia Center for Research in Reproduction Ligand Assay and Analysis Core (Charlottesville, VA). Details of the assay procedures can be found at http://www.medicine.virginia.edu/research/institutes-andprograms/crr/ligand-page. Serum FSH levels were measured using an FSH Milliplex MAP kit (Millipore).

Sperm quantification

Sperm preparations and quantifications were based on previously described procedures (Jimenez et al. 2010). The caudal portion of the epididymis along with vas deferens of adult mice were isolated and cut at various points with a razor blade to release sperm into pre-warmed modified Whitten’s Medium (100 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 5.5 mM glucose, 0.8 mM Na pyruvate, 4.8 mM lactic Acid, 20 mM HEPES and 1.7 mM CaCl2, pH 7.3). Following a 10 min incubation at 37°C, sperm in the supernatant were counted with a hemocytometer.

Assessment of sperm motility

Wild type and Prl3c1 null sperm were analyzed by CASA, using the Minitube Sperm Vision Digital Semen Evaluation system (version 3.5; Penetrating Innovations, Verona, WI), as previously described (Jimenez et al. 2010, 2011).

Seminiferous tubule staging and testicular compartment enrichment

Seminiferous tubule staging was determined according to criteria presented by Hess (Hess 1990). Testicular interstitium and seminiferous tubule enrichments were prepared as previously described (Dufau and Catt 1975). Briefly, decapsulated testes were transferred to DMEM/F12 Medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 2.5% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Sigma-Aldrich), 5% horse serum (Sigma-Aldrich), 15 mM HEPES, and 0.25 mg/ml collagenase (type IV; Sigma-Aldrich, C-5138) and incubated at 37°C for 20 min with continuous rotation. After settling for 5 min at room temperature, supernatants were transferred to a new tube and left on ice. Pellets were resuspended in the same medium and incubated as described above for another 10 min. Supernatants were combined and centrifuged at 600 g for 8 min to collect Leydig cells. The enriched Leydig cell preparations were used as a source of RNA and genomic DNA.

Immunohistochemical and immunofluorescence staining

All histochemical staining was performed on 10 μm frozen sections. After fixation with Bouin’s fixative at 4°C, testis sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with antibodies against cytochrome P450 side-chain cleavage enzyme (CYP11A1; 1:300) (Roby et al. 1991), MKI67 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; sc-15402, 1:100), or PLP-J (1:50) (Alam et al. 2008). Quantification of CYP11A1 immunostaining was obtained using the Automated Cellular Imaging System (San Juan Capistrano, CA). Confocal images were obtained with a Nikon C1 plus confocal system equipped with 543-nm HeNe, 488-nm Ar, and 405-nm diode lasers integrated into an Eclipse TE2000-U microscope with 20×/0.75 Plan Apochromat and 60×/1.40/0.21 oil Plan Apochromat objectives (Nikon Instruments, Inc., Melville, NY). Image acquisition was performed using Nikon EZ C1 software.

RNA analysis

RNA was extracted from tissues or cells using TRI Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription and quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) were performed as previously described (Kent et al. 2010; Konno et al. 2010). Primer sequences used for RT-PCR and qRT-PCR are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Rapid amplification of 5′ cDNA ends (5′ RACE)

Transcription start sites for Prl3c1-v1 and Prl3c1-v2 were determined with RNA isolated from anti-mesometrial uterine decidual tissues (gestation day 7.5) and enriched Leydig cell preparations using a 5′ RACE kit (Roche, Pleasanton, CA, 03353621001), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Primer sequences used in the 5′RACE: SP1-Rev568: 5′ CCACCTGTCAGGCTCGTTAT 3′; SP2-Rev518-495: 5′ GTAAAGCTTTTGCTCCCTCCAGAA 3′; SP3-Rev227-196: 5′ TGTGACGAGAAGAGGAAAGCAGATTGTCATAG 3′.

ChIP analysis

Decidual cell and enriched Leydig cell preparations were used as starting material for the ChIP analyses. Anti-mesometrial uterine decidual tissue was dissected from gestation day 7.5 implantation sites. Implantation sites were pooled from pregnant females. Immediately following dissection, the tissue was incubated in pre-warmed PBS supplemented with collagenase (type IV, 0.25 mg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich), trypsin (0.25 mg/ml, Invitrogen) and Dispase (2 units/ml, Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ) with continuous rotation at 37°C for 30 min. Decidual cells were collected from the dispersed cell suspensions by centrifugation at 600 g. Pellets were then washed with cold PBS and used for crosslinking and lysis. ChIP analysis was performed using an antibody against RNA polymerase II (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA; 05-623B) and the EZ-ChIP kit (EMD Millipore, 17–371) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sonication of decidual genomic DNA was achieved using Bioruptor 300 (Diagenode, Belgium) yielding DNA fragments ranging in length from 300 to 600 bp (Bioruptor 300 settings: power, high; sonication, 20 seconds on and 50 seconds off, 22 cycles). For the Leydig cell ChIP, freshly isolated enriched Leydig cells from testes were pooled. Cells were washed with cold PBS and the ChIP performed using EZ-ChIP kit. Sonication of the enriched Leydig cell genomic DNA was achieved using Bioruptor 300 yielding DNA fragments ranging in length from 300 to 600 bp (Bioruptor 300 settings: power, high; sonication, 20 seconds on and 50 seconds off, 15 cycles). Primers used for the ChIP PCR analysis are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

DNA methylation analysis

DNA methylation was determined using bisulfite sequencing, direct sequencing, and MultiNA-Combined Bisulfite Restriction Analysis (COBRA).

Bisulfite sequencing

Bisulfite PCR products were purified with the Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-up System (Promega, Madison, WI). For direct sequencing, purified PCR products were used for sequencing reactions with primers used for bisulfite PCR. PCR products were cloned into pGEM-T Easy Vector (Promega). Up to 16 plasmid clones were amplified with the Templiphi DNA Amplification Kit (GE Healthcare) and sequenced. The data were processed using the Quantification Tool for Methylation Analysis (QUMA) website (http://quma.cdb.riken.jp/).

COBRA with MultiNA microchip

Genomic DNA (2 to 8 μg) was digested with EcoRV at 37°C overnight. The DNA was extracted with phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (PCI; 25:24:1), precipitated with ethanol, and dissolved in TE. Five hundred ng of the EcoRV-digested DNA were bisulfite-converted using EZ DNA Methylation-Direct Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA), and eluted in M-Elution Buffer. One-fortieth of the DNA was used for PCR in 20 μl of a reaction containing 1× buffer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTP, and 0.25 μM each of primers with BIOTAQ HS DNA Polymerase (Bioline, Taunton, MA) under the following conditions: denaturation at 95°C for 7 min, and 43 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 30 sec at 58–61°C, and 1 min at 72°C, followed by 10 min at 72°C. Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 3. One-fifth of the PCR product was digested with HpyCH4IV or TaqI in 20 μl at 37°C overnight and analyzed with MultiNA Microchip Electrophoresis System (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The methylation level was calculated as previously described (Sato et al. 2010).

Cell culture

MA-10 mouse Leydig cells (a gift from Dr. Mario Ascoli, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA) were cultured in Waymouth’s MB752/1 Medium (Life Technologies) supplemented with 15% horse serum (Sigma-Aldrich) and 20 mM HEPES. TM3 mouse Leydig cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA; CRL-1714) were cultured in DMEM/F12 Medium (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 2.5% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Sigma-Aldrich), 5% horse serum, 15 mM HEPES. MLTC-1 mouse Leydig cells (ATCC, CRL-2065) were cultured in RPMI 1640 Medium (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% FBS. COS-7 African green monkey kidney fibroblast-like cells (ATCC, CRL-1651) were cultured in DMEM Medium (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% FBS. Cell number was assessed using MultiTox-Fluor Multiplex Cytotoxicity Assay (Promega, G9200), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Plasmids, transfection, subcellular fractionation, and western blotting

A Prl3c1-v1 cDNA was obtained from Open Biosystems (Thermo Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and used as a template for PCR amplification of the coding sequence for Prl3c1-v2. Prl3c1-v1 and Prl3c1-v2 coding sequences were cloned into pCMV6-Entry (Origene, Rockville, MD) using XhoI and EcoRV restriction sites generating constructs with inframe C-terminal FLAG tags. The accuracy of both expression constructs was confirmed by DNA sequencing. Cells were transfected with an empty pCMV6-Entry vector or with vectors containing tagged Prl3c1-v1 or Prl3c1-v2 using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies). Cells were harvested for subcellular fractionation 48 h after transfection using NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents (Thermo Scientific, 78833) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Transfection efficiencies for MLTC-1, MA-10, TM3, and COS7 cells were 72.2 ± 7.1%, 62.0 ± 6.2%, 70.0 ± 6.4%, and 88.0 ± 4.2%, respectively. Western blotting procedures were performed as previously described (Deb et al. 1993). PLP-J V1-FLAG and PLP-J V2-FLAG were detected with antibody to the FLAG tag (Sigma-Aldrich, F3165, 1:2,500). Antibodies against Histone H3 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA; ab94817, 1:10,000) and GAPDH (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA; MAB374, 1:7,500) were used as controls to monitor the integrity of the subcellular fractionation.

Statistical analysis

Differences between two groups were assessed by Student’s t test. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. P values less than 0.05 are considered statistically significant.

Results

PRL family gene expansion and Prl3c1 gene disruption

Gene duplication represents a potential mechanism for acquisition of species-specific physiological traits (Ohno 1970; Kaessmann 2010). Several genes associated with reproduction have undergone expansions (Rawn and Cross 2008). Prolactin (PRL), a well-conserved hormone/cytokine best known for its actions on the reproductive tract and mammary gland (Freeman et al. 2000; Bachelot and Binart 2007), has undergone species-specific gene duplication (Soares 2004; Soares et al. 2007). In some species, the ancestral PRL served as a template for the birth of new genes (mouse, rat, and cow), while in other species, exemplified by the human, cat, and dog, only the PRL ortholog is present in the genome (Soares 2004; Soares et al. 2007). Mutagenesis experiments suggested that a driving force in the expansion of the mouse PRL family was associated with pregnancy-dependent adaptations to physiological stressors (Ain et al. 2004; Soares 2004; Alam et al. 2007; Soares et al. 2007). Mouse Prl contributes to the regulation of pregnancy and mammary gland development (Horseman et al. 1997), whereas Prl4a1 and Prl8a2 possess roles in adaptations to environmental challenges during pregnancy (Ain et al. 2004; Alam et al. 2007). Prl3c1 encodes a protein called PRL like protein-J (PLP-J, also referred to as PRL3C1) and was originally identified in uterine decidua of the mouse and rat (Hiraoka et al. 1999; Ishibashi et al. 1999; Toft and Linzer 1999; Dai et al. 2000). PLP-J was shown to act as a heparin-binding cytokine contributing to growth regulation of cells within the uterus (Alam et al. 2008). These observations prompted the generation of mice possessing a null mutation at the Prl3c1 locus, with the expectation of a pregnancy-related phenotype. The entire coding sequence of Prl3c1 was replaced with an inframe β-galactosidase (LacZ) cassette (inserted at the ATG codon in the first exon) followed by a neomycin resistance cassette (Fig. 1A,B). The mutation was successfully transmitted through the germline.

Fig. 1. Prl3c1 mutant mice exhibit an abnormal male reproductive tract phenotype.

A, Schematic of the mouse Prl3c1 locus and the targeting construct. B, PCR analysis of genomic Prl3c1 locus from wild type (+/+), heterozygous (+/−) and null (−/−) animals. C, Gross appearance of the scrotal area on postnatal day 21 of wild type (+/+) and Prl3c1 null (−/−) mice. D, Gross appearance of adult testis of wild type and Prl3c1 null mice. E, Testis-to-body weight ratio of wild type (2–2.5 months, n=14; 4–5 months, n=8) and Prl3c1 null (2–2.5 months, n=20; 4–5 months, n=15) mice. F, CYP11A1 immunofluorescence staining of testis cross-sections from wild type and Prl3c1 null mice. G, Quantification of CYP11A1 positive staining area/total cross-section area of wild type and Prl3c1 null testes, n=5 testes per group. H–M, MKI67 immunofluorescence staining of testis cross-sections from wild type and Prl3c1 null mice. Scale bar: 50 μm. *P<0.05; **P<0.001.

Assessment of fertility

Prl3c1 null and wild type males exhibited similar fertility. All wild type males successfully impregnated wild type females (n=13 males generated n=28 seminal plug positive females, leading to 28 pregnancies; 100% success rate). Prl3c1 null males also successfully impregnated wild type females (n=12 males generated n=24 seminal plug positive females, leading to 19 pregnancies; 79% success rate). All wild type females (n=13) effectively mated during cohabitation with wild-type males, which led to 12 pregnancies (n=12; litter size: 10.5 ± 0.4). The Prl3c1 null females were subfertile. Only 58% (7 of 12), mated during cohabitation with wild type males and only 57% of the seminal plug-positive females were pregnant on gestation day 9.5 (n=4; litter size: 11.0 ± 3.9). In this report, we focus our analysis on the reproductive tract phenotype of Prl3c1 null male mice.

Prl3c1 null mice have an altered male reproductive tract phenotype

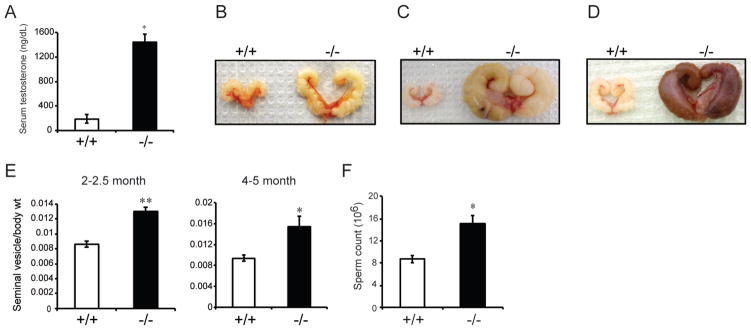

Mice possessing a null mutation at the Prl3c1 locus exhibited an unexpected male reproductive tract phenotype. At the time of weaning Prl3c1 null male mice exhibited precocial development of the scrotal region (Fig. 1C). The scrotal anomaly was associated with large testes (Fig. 1D,E; Supplementary Table 3). Since body weights were significantly greater in the Prl3c1 mutant males, we have included both relative and absolute testis measurements (Fig. 1E; Supplementary Table 3). Within the testis, interstitial compartments from Prl3c1 deficient mice were significantly expanded and contained more MKI67-positive cells when compared to testes of wild type mice (Fig. 1F–M). Postnatal testis development is associated with an initial expansion and then a decline in Leydig cell progenitors (proliferative population) and a subsequent increase in adult Leydig cells (post-mitotic population) (Benton et al. 1995; Ge et al. 2005; Chen et al. 2010; Stanley et al. 2010). Most interestingly, several Leydig cell progenitor-associated transcripts remained elevated in the adult Prl3c1 null testis (Fig. 2A). Conversely, an indicator of adult Leydig cells, Hsd3b6, failed to exhibit the expected developmental increase in the adult Prl3c1 null testis and instead, Hsd3b1, another 3β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase isoform with similar substrate specificity was elevated in the adult Prl3c1 null testis (Fig. 2B). Two transcripts encoding 5α reductase were decreased in Prl3c1 null testes (Fig. 2B). Other testicular transcripts encoding proteins participating in steroidogenesis were more modestly affected by Prl3c1 disruption (Fig. 2C). Indices of testicular function were also examined. Serum testosterone levels were elevated, androgen-responsive tissues were hyper-stimulated, and sperm production was significantly greater in Prl3c1 null versus wild type male mice (Fig. 3; Supplementary Table 3). Diameters of seminiferous tubules and the ratio of stage VIII seminiferous tubules to the total numbers of seminiferous tubules per cross-sectional area of the testis were similar in Prl3c1 null and wild type testis; however, the Prl3c1 null testes had significantly more seminiferous tubules per cross-section than did the wild type testis (wild type: 228.2 ± 7.2 versus Prl3c1 null: 347.7 ± 5.8, P<0.001). Wild type and Prl3c1 null sperm exhibited similar patterns of motility. Seminal vesicle glands continued to grow as the Prl3c1 null mice aged and showed pathologic changes, including exhibiting regions of necrosis and hemorrhage (Fig. 3C,D). Overall, the evidence supported a hyperfunctionality of the Prl3c1 null testis driven by an alteration of the developmental maturation of Leydig cells. Prl3c1 mutant Leydig cells retain their ability to proliferate and functionally generate a hyperandrogenic condition.

Fig. 2. Assessment of Leydig cell developmental states in wild type and Prl3c1 null mice.

A, qRT-PCR analysis of transcripts associated with the progenitor Leydig cell state in wild type postnatal day 15 (PND 15), adult (2.5–4 months) wild type and Prl3c1 null testes. PND15 represents a transition point from progenitor to adult Leydig cells. qRT-PCR analysis of transcripts for Prl3c1 (B) and transcripts encoding proteins involved in steroid hormone biosynthesis (B, Hsd3b, Srd5a2, and Srd5a3; C, Star, Cyp11a1, Cyp17a1, and Hsd17b3) in adult wild type and Prl3c1 null testes (n=6; *P<0.05, **P<0.001).

Fig. 3. Measures of testicular function in wild type and Prl3c1 null mice.

A, Serum testosterone levels from wild type (n=8) and Prl3c1 null (n=10) male mice (3.5–4.5 months). B, Gross appearance of seminal vesicles from 4–5 month wild type and Prl3c1 null mice. C and D, Gross appearance of seminal vesicles from 11–12 month wild type and Prl3c1 null mice. E, Seminal vesicle-to-body weight ratio of wild type (2–2.5 months, n=14; 4–5 months, n=8) and Prl3c1 null (2–2.5 months, n=20; 4–5 months, n=15) mice. F, Total sperm count of wild type and Prl3c1 null mice (n=5 per genotype). Scale bar: 50 μm. *P<0.05; **P<0.001.

A linkage between the Prl3c1 null phenotype and Prl3c1 gene expression was explored. In a survey of several tissues from wild type male mice, Prl3c1 transcripts were prominently detected in the testis and preferentially localized to the interstitial compartment within the testis, as was PLP-J immunoreactivity (Fig. 4A–C). LacZ activity corresponding to activation of the Prl3c1 gene in heterozygous Prl3c1 mutant testes was co-localized with CYP11A1 immunoreactivity, demonstrating Prl3c1 gene activation specifically within Leydig cells (Fig. 4D). Localization of Prl3c1 to Leydig cells of the mouse testis has been previously reported (Yang et al. 2014). Testicular Prl3c1 expression showed a developmental ontogeny similar to adult Leydig cell marker genes, including Hsd3b6 (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4. Prl3c1 transcript and the PLP-J protein are expressed in Leydig cells of the testis.

A, Tissue survey (RT-PCR analysis) for Prl3c1 transcripts in various tissues from male C57BL/6 mice. B, RT-PCR analysis for Prl3c1 transcripts in testicular interstitium and seminiferous tubule compartments. Insl3 and Dmrt1 were included as controls for the interstitium and seminiferous tubule compartments, respectively. C, Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining for PLP-J on tissue sections from wild type testis. D, The Prl3c1 locus is transcriptionally active in Leydig cells of mice with β-galactosidase (LacZ) knocked into the Prl3c1 locus. Left panel: LacZ reporter activity; middle panel: immunofluorescence staining for CYP11A1; right panel: merged image of LacZ and CYP11A1 staining. LacZ reporter activity was localized to CYP11A1 positive Leydig cells in mice. Scale bar: 250 μm.

Fig. 5. Ontogeny of Prl3c1 and steroidogenic enzyme transcripts in testes of wild type mice.

A, RT-PCR analysis of Prl3c1 transcript expression in testes from postnatal days 5 to 45 (n=3 per day). Positive control (P.C.) is adult testis. Insl3 and Gapdh transcript analyses were used as internal controls. B and C, qRT-PCR measurements of transcripts for Prl3c1 (B) and transcripts encoding proteins involved in steroid hormone biosynthesis (B, Hsd3b and Srd5a2; C, Hsd17b3, Hsd3b1, Srd5a3) in testes at postnatal days 15 (D15), 21 (D21), and 45 (D45) (n=6, *P<0.05, ** P<0.001, compared to D15).

Collectively, the phenotype suggested that PLP-J expression by Leydig cells regulates programming of the setpoint for testicular growth and function. In the absence of a functional Prl3c1 gene the setpoint for testicular size and functional output was increased.

The testicular homeostatic setpoint control system includes the pituitary

The normal core functions of the testis are driven by an efficient homeostatic interplay of hypothalamic and pituitary signals, which are responsive to the testicular output they control. Since LH is the primary driver of Leydig cell function and Leydig cells are hyperfunctional in the Prl3c1 null mouse, we examined the contributions of LH to the Prl3c1 null phenotype. Serum LH levels were higher in Prl3c1 null mice, as was the Lhb transcript concentration of the pituitary (Fig. 6A,B). Elevations in LH prompted serum FSH and Fshb transcript measurements. Serum FSH levels did not differ between the genetic groups; however, Fshb transcript concentrations were significantly lower in pituitaries from Prl3c1 null males (Fig. 6C,D). Thus, there is a potential contribution of the pituitary, and more specifically elevated circulating LH, to the regulation of the Leydig cell phenotype observed in the Prl3c1 null testis. The male HPG axis appears to be operating in a unidirectional mode in Prl3c1 null mice with a distorted setpoint for negative feedback modulation by gonadal testosterone.

Fig. 6. The testicular homeostatic setpoint control system includes the pituitary.

A, Serum LH levels in wild type (n=8) and Prl3c1 null (n=10) adult male mice. *P<0.05. B, Lhb transcript levels in pituitaries of wild type (n=5) and Prl3c1 null (n=7) adult male mice analyzed by qRT-PCR. **P<0.001. C, Serum FSH levels in wild type (n=18) and Prl3c1 null (n=18) adult male mice. D, Fshb transcript levels in pituitaries of wild type (n=5) and Prl3c1 null (n=7) adult male mice analyzed by qRT-PCR. **P<0.001.

The Prl3c1 gene is a template for two transcripts

Prl3c1 transcripts expressed in uterine decidua and testes were compared and determined to be distinct, each utilizing different first exons driven by alternative promoters (Fig. 7). Decidual and Leydig cell Prl3c1 transcription start sites and promoters were identified by 5′ RACE (Supplementary Fig. 1A,B) and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), using antibodies to RNA polymerase II (POL II; Fig. 7B), respectively. The two transcripts were operationally defined as Prl3c1-v1 and Prl3c1-v2 (Fig. 7C). The transcription start site for Prl3c1-v1 was located 46 bp upstream of the ATG for Prl3c1-v1, whereas the transcription start site for Prl3c1-v2 was located 136 bp upstream of the ATG for Prl3c1-v2 (Supplementary Fig. 1A,B). An upstream promoter directs Prl3c1-v1 transcription (Fig. 7B,C). The Prl3c1-v1 transcript contains an upstream exon defined as Exon 1a and encodes a secreted protein previously characterized from the uterine decidua (Alam et al. 2008), which we refer to as PLP-J V1 (Fig. 7C). A second promoter, embedded within the first intron of the Prl3c1 gene, directs Prl3c1-v2 transcription (Fig. 7B,C). The Prl3c1-v2 transcript contains an alternate first exon defined as Exon 1b and encodes a protein termed PLP-J V2 (Fig. 7C). Within the testis, the alternative promoter is operative in Leydig cells. This pattern of testicular Prl3c1-v2 expression is conserved in fifteen different mouse strains (Supplementary Fig. 1C).

Fig. 7. The Prl3c1 gene is a template for two transcripts with distinct tissue expression patterns.

A, Prl3c1 transcript-specific RT-PCR analysis revealed tissue-restricted expression patterns for Prl3c1-v1 (decidua) and Prl3c1-v2 (testis). B, ChIP-qPCR analysis for RNA POL II at regions proximal to Exons 1a of Prl3c1-v1 (V1) and 1b of Prl3c1-v2 (V2) in decidua and Leydig cells. Locations of primer sets used in ChIP-qPCR are depicted as arrowheads shown in panel C (n=4, *P<0.05 compared to IgG control). C, Schematic representation of transcription start sites for Prl3c1-v1 (decidua) and Prl3c1-v2 (Leydig cells) as determined by 5′RACE (see also Supplementary Fig. 1A,B).

Origin of the testicular homeostatic setpoint control system

Transposable elements are sources of genetic information that have contributed to the evolution of the mammalian genome (Kaessmann 2010; Rebollo et al. 2012; Chuong et al. 2017). They are vestiges of viral infections and exist as repetitive sequences dispersed throughout the genome (Kidwell and Lisch 2001; Rebollo et al. 2012). Although the host organism has defense mechanisms for silencing transposable elements, in some cases these elements escape repression and contribute to the birth of new genes and regulatory information controlling gene transcription (Kidwell and Lisch 2001; Jern and Coffin 2008; Rowe and Trono 2011; Feschotte and Gilbert 2012; Rebollo et al. 2012; Chuong et al. 2017). Transposable element contributions to the regulation of reproduction have been described (Rebollo et al. 2012; Feschotte and Gilbert 2012; Emera and Wagner 2012; Chuong et al. 2017).

Comparison of mouse versus rat Prl3c1 loci established a connection between the testicular homeostatic setpoint control system and the insertion of a composite transposable element within the mouse Prl3c1 locus. The rat possesses a Prl3c1 ortholog, which is expressed in uterine decidua (Hiraoka et al. 1999; Ishibashi and Imai 1999; Toft and Linzer 1999; Dai et al. 2000) but not in testes (Fig. 8A). Closer inspection of the rat Prl3c1 gene revealed that it possesses a shorter first intron that lacks Exon 1b, which is characteristic of the mouse Prl3c1-v2 transcript (Fig. 8B). The extended length of the first intron of mouse Prl3c1 was attributed to the insertion of a composite transposable element consisting of two parts of an LTR-type element referred to as RMER17D_MM separated by a LINE element (L1 Mus_3 end; Fig. 8C). The RMER17D_MM element is restricted in its genomic distribution. Of the 4,977 RMER17D_MM insertion sites (80–100% sequence identity) within the mouse genome, 76.79% (3,823 copies) are located within intergenic regions, 23.2% (1,149 copies) in intronic regions, and 0.01% (5 copies) within exons. Insertion of the composite transposable element into the first intron of the mouse Prl3c1 gene provides an alternative promoter and an alternative first exon (Exon 1b), structures absent from the rat Prl3c1 locus.

Fig. 8. Origin and species specificity of the testicular homeostatic setpoint control system.

A, RT-PCR analysis for Prl3c1 transcripts with primers targeting various exons of the rat Prl3c1 gene in testes of Fischer 344 (F344), Holtzman Sprague Dawley (HSD) and Brown Norway (BN) rats. Decidua tissue (HSD, gestation day 7.5) was included as a positive control. B, PCR amplification of the first intron of the Prl3c1 gene from the mouse (C57BL/6) and rat (BN). Schematic diagram of exon-intron structure indicates the locations of the primers used for amplification. C, Schematic comparison of the mouse and rat Prl3c1 genes reveals a longer first intron in the mouse due to the insertion of a composite transposable element (TE), which contains Exon 1b of Prl3c1-v2. D, PCR amplification of the first introns of the Prl3c1 genes from M. musculus, M. spretus, M. caroli, M. pahari, and R. norvegicus. E, Schematic representations of the first introns of the Prl3c1 genes from M. musculus, M. spretus, M. caroli, M. pahari, and R. norvegicus. Sequence identity comparisons are with the M. musculus sequence. F, Phylogenetic tree based on the nucleotide sequences for the first introns of Prl3c1 genes from M. musculus, M. spretus, M. caroli, M. pahari, and R. norvegicus. G, Primer validation for M. caroli and M. pahari. Schematic diagram indicates the locations of the two sequence-specific primer sets used for detection of Prl3c1 transcripts in testes from M. caroli and M. pahari. Primer sequences were based on partially sequenced coding regions of M. caroli (GenBank Accession No., KJ125427) and M. pahari (GenBank Accession No., KJ125428) Prl3c1 genes and validated by PCR amplification of corresponding Prl3c1 genomic regions with genomic DNA from these species. H, RT-PCR analysis for Prl3c1 transcripts in testes of M. musculus, M. spretus, M. caroli, and M. pahari. Two sets of sequence specific primers were used for M. caroli and M. pahari. I, Annotated schematic of the first intron of Prl3c1 from M. musculus and M. caroli. Note the prominent differences in the organization of RMER17D in M. musculus versus M. caroli.

Rapidly evolving testicular homeostatic setpoint control system

The rat is estimated to have diverged from the mouse approximately 25.2 million years ago (Mya) (Hedges et al. 2006). We reasoned that other Mus species sharing a closer evolutionary history with M. musculus (divergence from M. musculus: M. spretus, 1.8 Mya; M. caroli, 3.2 Mya; M. pahari, 7.9 Mya) (Guenet and Bonhomme 2003; Petkov et al. 2004; Keane et al. 2011) could provide additional insights into the evolutionary origin of this alternative Prl3c1 transcript. Nucleotide sequences for the first intron of the Prl3c1 gene corresponding to each of the four Mus species were determined and compared (Fig. 8D–F). M. musculus and M. spretus possess a virtually identical organization of Exon 1a and Intron 1, including insertion of the composite transposable element with Exon 1b, and testis expression of Prl3c1-v2 but not Prl3c1-v1 (Fig. 8D–H) (Keane 2011). The extended Intron 1 with components of the composite transposable element is also present in M. caroli (GenBank Accession No., KF767571); however, the organization of the composite transposable element shows marked differences and this species lacks testicular expression of either Prl3c1-v1 or Prl3c1-v2 (Fig. 8D–I). The more divergent M. pahari lacks the composite transposable element and does not express either Prl3c1-v1 or Prl3c1-v2 within its testes (GenBank Accession No., KF767572; Fig. 8D–H). Consistent with the Leydig cell static actions of PLP-J V2 in M. musculus, M. pahari lacks testicular Prl3c1 expression and interestingly possesses a proportionately larger interstitial compartment within its testis when compared to M. musculus or M. spretus testes (Montoto et al. 2012). Collectively, these data indicate that the Prl3c1 locus exhibited significant changes within a short evolutionary timeframe. Furthermore, comparisons of rodent amino acid sequences indicated that proteins encoded by the Prl3c1 gene have undergone positive selection (Chuong et al. 2010), a measure of a rapidly evolving gene.

Regulation of Prl3c1-v1 versus Prl3c1-v2 expression

A conserved method for controlling regulatory elements and defense against inappropriate activation of transposable elements is via DNA methylation (Rowe and Trono 2011). Consequently, we investigated DNA methylation throughout the mouse Prl3c1 locus, in uterine decidua (Prl3c1-v1 expression), enriched Leydig cells isolated from the adult mouse testis, (Prl3c1-v2 expression), and liver (negative control) using bisulfite sequencing, direct sequencing, and MultiNA-Combined Bisulfite Restriction Analysis (COBRA) (Yagi et al. 2008; Hayakawa et al. 2012). Collectively, the analyses indicated that DNA methylation status at the Prl3c1 locus was different in decidual cells versus Leydig cells. A region approximately 2 kb upstream of the Prl3c1-v1 transcription start site was hypomethylated in decidual cells and hypermethylated in Leydig cells, whereas the reciprocal was true for the proximal regulatory sequence immediately upstream of Exon 1b, including parts of the composite transposable element (Supplementary Fig. 2–4). The results are consistent with the idea that tissue specific DNA methylation at the Prl3c1 locus could contribute to the differential regulation of Prl3c1-v1 and Prl3c1-v2.

The two Prl3c1 transcripts encode proteins with distinct intracellular targeting and actions

Exon 1a of the Prl3c1 gene encodes the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of the Prl3c1-v1 transcript and the initial portion of the signal peptide for the PLP-J V1 protein (Alam et al. 2007). In contrast, Exon 1b is a noncoding exon, contributing solely to the 5′ UTR of the Prl3c1-v2 transcript. The common Exon 2 contributes the translation initiation codon of the Prl3c1-v2 transcript. Prominent differences in the N-terminal portion of the PLP-J V1 and predicted PLP-J V2 proteins prompted a comparison of their intracellular distributions in mouse Leydig cell lines (TM3, MA-10, and MLTC-1) and COS7 cells following transfection of expression vectors encoding FLAG-tagged PLP-J V1 and PLP-J V2 proteins. Western blotting of nuclear and cytosolic lysates of transfected MLTC-1 and COS7 cells demonstrated that PLP-J V1 was preferentially localized to the cytoplasm, whereas PLP-J V2 was targeted predominantly to the nucleus (Fig. 9A; Supplementary Fig. 5A). Interestingly, part of the mechanism of action of PRL in T-lymphocytes requires its nuclear translocation (Clevenger et al. 1991). We next determined whether ectopic expression of PLP-J V1 or PLP-J V2 affected MLTC-1 Leydig cell behavior. PLP-J V2 inhibited MLTC-1 Leydig cell proliferation, whereas PLP-J V1 did not significantly affect cell number (Fig. 9B,C). PLP-J V2 also effectively inhibited TM3, MA-10, and COS7 cell proliferation (Supplmentary Fig. 5B–D). TM3 cells possess features resembling Leydig cell progenitors, while MLTC-1 cells represent a more mature Leydig cell population (Supplementary Fig. 6A) (Mather 1980; Rahman and Huhtaniemi 2004). Ectopic expression of PLP-J V2 in MLTC-1 Leydig cells did not affect transcript levels for steroidogenic enzymes but did affect the expression of a subset of Leydig cell progenitor markers (Supplementary Fig. 6B–D). In contrast, ectopic expression of PLP-J V2 in TM3 Leydig cells stimulated Hsd3b1 and Hsd3b6 transcript levels, similar to LH treatment, but did not affect the expression of Leydig cell progenitor markers (Supplementary Fig. 6E–G). The absence of an effect of ectopic expression of PLP-J V1 on TM3 cell cycle or steroidogenesis has been previously reported (Yang et al. 2014). Thus, ectopic PLP-J V2 can alter Leydig cell behavior, but its actions are context-dependent and influenced by the developmental state of the target Leydig cell population.

Fig. 9. Intracellular distribution and distinct functions of PLP-J V1 versus PLP-J V2.

FLAG-tagged PLP-J V1 and FLAG-tagged PLP-J V2 were ectopically expressed in MLTC-1 Leydig cells or COS7 cells (1 μg/ml). Cells transfected with an empty vector were used as a control (1 μg/ml). A, Subcellular fractionation followed by western blotting for FLAG (Cyto: cytoplasm; Nu: nucleus). Western blotting for GAPDH and Histone H3 were used to monitor the integrity of the cytoplasmic and nuclear preparations, respectively. B, Effects of ectopic expression of Prl3c1-v1 (left panel) or Prl3c1-v2 (right panel) on MLTC-1 Leydig cell numbers following 72 h of culture. Cells were cultured in 96 well plates with 0.1 ml of medium/well (n=6, **P<0.001 compared to empty vector control). C, Representative images of MLTC-1 cells transfected with empty vector, Prl3c1-v1, or Prl3c1-v2 (1 μg/ml) following 72 h of culture.

To summarize, the contributions of the composite transposable element resulted in the use of an alternative exon and the production of a protein targeted to the nucleus with Leydig cell-static actions. Such actions are consistent with the testiculomegaly and Leydig cell hyperplasia observed in Prl3c1 deficient mice (Fig. 1D–M).

Overview

The “big” testis phenotype in Prl3c1 null mice is associated with a disruption in the HPG axis characterized by concomitant elevations in LH and testosterone and the consequences of their actions; a condition known as hypergonadotropic-hypergonadal-hyperandrogenism. Characterization of the Prl3c1 null phenotype led to the discovery of a homeostatic setpoint control system programming testicular growth and function.

Discussion

Male fertility is dependent upon the appropriate functioning of the HPG axis (Achermann and Jameson 1999; Hedger and de Kretser 2000; Matzuk and Lamb 2008). Each functional unit within the axis works as part of a homeostatic mechanism to precisely control core testicular functions, which include testosterone and sperm production. Two important features of the mammalian testis are evident: 1) there is a wide range of testis size and functional output across mammalian species; 2) within a species there are constraints governing testicular size and function. Dysregulated growth and function of the male gonads have consequences. Deficiencies are associated with subfertility and infertility, whereas excesses have costs to adult male health, including androgen-driven hyperplasia that can lead to neoplasia, and potentially negative consequences on social structure (Short 1997; Hedger and de Kretser 2000; Mascaro et al. 2013). Species-specific regulatory pathway(s) controlling this elemental reproductive process are poorly understood. We have discovered a reproductive trait with its evolutionary origins associated with gene duplication and co-optation of transposable elements. In the mouse, the size of the testis and its capacity to produce testosterone and sperm are modulated by the recruitment of a composite transposable element to the Prl3c1 locus and its contribution to the regulation and biosynthesis of a unique protein. Prl3c1 is a gene within the expanded PRL family. This novel control system impacts the establishment of the homeostatic setpoint determining the size and function of the testis. Although the existence of this testicular homeostatic setpoint control system is restricted to the mouse, species-specific epiregulation of the male reproductive axis may represent a universal concept, contributing to each species’ reproductive success. Indeed, the testis is a common site for the expression of new and rapidly evolving genes with restricted phylogenetic distributions (Turner et al. 2008; Heinen et al. 2009; Chen et al. 2013). The widespread existence of species-specific modulation of the male reproductive axis evokes questions with broader implications. Are the growth and function of other organs governed by species-specific mechanisms? Are these species-specific mechanisms prone to dysregulation and do they represent potential therapeutic targets for treating disease? The existence of layers of control that are not conserved among species represents a challenge, as well as an opportunity to investigate physiological regulation and its relationship to disease.

Supplementary Material

A and B, transcription start site (TSS) determination was performed using 5′ RACE from decidual (A) and testicular tissue (B). The bolded and underlined atg indicates the translation start codon for Prl3c1-v1 (A) and Prl3c1-v2 (B). C, RT-PCR analysis of Prl3c1-v1 and Prl3c1-v2 transcripts in the testis from fifteen mouse strains. Please note that Prl3c1-v2 transcripts were present in all strains, whereas Prl3c1-v1 transcripts were not detectable. Positive controls for Prl3c1-v1 = decidua from gestation day 7.5; Prl3c1-v2 = adult testis. Gapdh was used as a loading control.

A, Schematic of Prl3c1 genomic locus and composite transposable element (gray and black bars proximal to TSS of Prl3c1-v2) identified by Repeat Masker. CpG sites situated within blue regions (1, 2, 3, 4 and 5) were analyzed for methylation. B, Bisulfite sequencing results were obtained from decidua (n=6), primary Leydig cells (n=6), and liver (n=3). Open and closed circles represent unmethylated and methylated CpG sites, respectively.

A, Schematic of Prl3c1 genomic locus, composite transposable element, and CpG sites (CG 1–8). CpG sites situated in regions (3 and 4) located within the composite transposable element were analyzed for methylation. B, Results of direct bisulfite sequencing indicate CpG sites (2, 3, 4, 6 and 7) were hypomethylated in Leydig cells (n=6) and hypermethylated in decidua (n=7) and liver (n=6).

A, Schematic of Prl3c1 genomic locus, composite transposable elements, and CpG sites (red arrows). CpG sites situated in blue regions (3 and 5) within the composite transposable elements were analyzed for methylation. B, MultiNA-COBRA results indicate CpG sites (3 and 5) were hypomethylated in Leydig cells (n=6) but hypermethylated in decidua (n=7) and liver (n=6).

A, FLAG-tagged PLP-J V2 was ectopically expressed in COS7 cells. Subcellular fractioned proteins were analyzed by western blotting with anti-FLAG antibodies (Cyto: cytoplasm; Nu: nucleus). Western blotting for GAPDH and HISTONE H3 were used to monitor the integrity of the cytoplasmic and nuclear preparations, respectively. COS7 cells transfected with an empty vector were used as a control. B–D, Effects of ectopic expression of empty vector or Prl3c1-v2 on TM3 (B), MA-10 (C), and COS7 (D) cell numbers following 72 h of culture. **P<0.001 compared to empty vector control.

A, qRT-PCR analysis of progenitor Leydig cell transcript expression in MLTC-1 (open bars) and TM3 (filled bars) Leydig cells. MLTC-1 Leydig cell Hsd3b1 and Hsd3b6 transcript responses to ectopic Prl3c1-v2 expression (B) and LH treatment (C). D, MLTC-1 Leydig cell Akr1c14, Pmp22, and Ptma (Leydig progenitor cell-associated) transcript responses to ectopic Prl3c1-v2 expression. TM3 Leydig cell Hsd3b1 and Hsd3b6 transcript responses to ectopic Prl3c1-v2 expression (E) and LH treatment (F). G, TM3 Leydig cell Akr1c14, Pmp22, and Ptma (Leydig progenitor cell-associated) transcript responses to ectopic Prl3c1-v2 expression. *P<0.05, **P<0.001.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jacques Tremblay (Laval University) and Drs. Gustavo Blanco, T. Rajendra Kumar, Gladys Sanchez, and Ossama Tawfik (University of Kansas Medical Center) for their advice and suggestions regarding the execution of the experimentation. We also thank Dr. Sumedha Gunewardena (University of Kansas Medical Center) for assistance with the bioinformatic analysis, Dr. Vincent Lynch (University of Chicago) for advice with the RNA POL II ChIP analysis, and Dr. Curtis Klaassen for providing the testis samples used in the mouse strain survey. We are very appreciative of the valuable feedback and advice provided by Dr. Gunter Wagner (Yale University), R. Michael Roberts (University of Missouri), Dr. Dixie Mager (University of British Columbia), and Dr. Justin Blumenstiel (University of Kansas) during various stages of the research. This work was supported by a grant from the NIH HD055523 and a National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences postdoctoral fellowship to P.B. (T32-ES007079). The University of Virginia Center for Research in Reproduction Ligand Assay and Analysis Core is supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD)/National Institutes of Health (Specialized Cooperative Centers Program in Reproduction and Infertility Research (SCCPIR) grant U54-HD28934.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: There is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

References

- Achermann JC, Jameson JL. Fertility and infertility: genetic contributions from the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. Molecular Endocrinology. 1999;13:812–818. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.6.0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ain R, Dai G, Dunmore JH, Godwin AR, Soares MJ. A prolactin family paralog regulates reproductive adaptations to a physiological stressor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2004;101:16543–16548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406185101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam SMK, Konno T, Dai G, Lu L, Wang D, Dunmore JH, Godwin AR, Soares MJ. A uterine decidual cell cytokine ensures pregnancy-dependent adaptations to a physiological stressor. Development. 2007;134:407–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.02743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam SM, Konno T, Sahgal N, Lu L, Soares MJ. Decidual cells produce a heparin-binding prolactin family cytokine with putative intrauterine regulatory actions. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283:18957–18968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801826200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amory JD, Bremner W. Endocrine regulation of testicular function in men: implications for contraceptive development. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2001;182:175–179. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00562-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachelot A, Binart N. Reproductive role of prolactin. Reproduction. 2007;133:361–369. doi: 10.1530/REP-06-0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton L, Shan LX, Hardy MP. Differentiation of adult Leydig cells. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 1995;53:61–68. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(95)00022-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkhead T. Promiscuity: An evolutionary history of sperm competition. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bronson FH. Mammalian reproductive biology. The University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Stanley E, Jin S, Zirkin BR. Stem Leydig cells: from fetal to aged animals. Birth Defects Research (Part C) 2010;90:272–283. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Krinsky BH, Long M. New genes as drivers of phenotypic evolution. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2013;14:645–660. doi: 10.1038/nrg3521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuong EB, Tong W, Hoekstra HE. Maternal-fetal conflict: rapidly evolving proteins in the rodent placenta. Molecular Biology of Evolution. 2010;27:1221–1225. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuong EB, Elde NC, Feschotte C. Regulatory activities of transposable elements: from conflicts to benefits. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2017;18:71–86. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clevenger CV, Altmann SW, Prystowsky MB. Requirement of nuclear prolactin for interleukin-2-stimulated proliferation of T lymphocytes. Science. 1991;253:77–79. doi: 10.1126/science.2063207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai G, Wang D, Liu B, Kasik JW, Müller H, White RA, Hummel GS, Soares MJ. Three novel paralogs of the rodent prolactin gene family. Journal of Endocrinology. 2000;166:63–75. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1660063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deb S, Hamlin GP, Roby KF, Kwok SCM, Soares MJ. Heterologous expression and characterization of prolactin-like protein-A. Identification of serum binding proteins. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1993;268:3298–3305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desjardins C. Endocrine regulation of reproductive development and function in the male. Journal of Animal Science. 1978;47:56–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufau ML, Catt KJ. Gonadotropic stimulation of interstitial cell functions of the rat testis in vitro. Methods in Enzymology. 1975;39:252–271. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(75)39024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emera D, Wagner GP. Transposable element recruitments in the mammalian placenta: impacts and mechanisms. Briefings in Functional Genomics. 2012;11:267–276. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/els013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett DW, Neaves WR, Flores MN. Comparative observations on intertubular lymphatics and the organization of the interstitial tissue of the mammalian testis. Biology of Reproduction. 1973;9:500–532. doi: 10.1093/biolreprod/9.5.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feschotte C, Gilbert C. Endogenous viruses: insights into viral evolution and impact on host biology. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2012;13:283–296. doi: 10.1038/nrg3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman ME, Kanyicska B, Lerant A, Nagy G. Prolactin: structure, function, and regulation of secretion. Physiological Reviews. 2000;80:1523–1631. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.4.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge R-S, Dong Q, Sottas CM, Chen H, Zirkin BR, Hardy MP. Gene expression in rat Leydig cells during development from the progenitor to adult stage: a cluster analysis. Biology of Reproduction. 2005;72:1405–1415. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.037499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenet J-L, Bonhomme F. Wild mice: an ever-increasing contribution to a popular mammalian model. Trends in Genetics. 2003;19:24–31. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(02)00007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa K, Nakanishi MO, Ohgane J, Tanaka S, Hirosawa M, Soares MJ, Yagi S, Shiota K. Bridging sequence diversity and tissue-specific expression by DNA methylation in genes of the mouse prolactin superfamily. Mammalian Genome. 2012;23:336–345. doi: 10.1007/s00335-011-9383-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedger MP, de Kretser DM. Leydig cell function and its regulation. Results and Problems in Cell Differentiation. 2000;28:69–110. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-48461-5_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges SB, Dudley J, Kumar S. TimeTree: a public knowledge-base of divergence times among organisms. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2971–2972. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinen TJ, Staubach F, Häming D, Tautz D. Emergence of a new gene from an intergenic region. Current Biology. 2009;19:1527–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess RA. Quantitative and qualitative characteristics of the stages and transitions in the cycle of the rat seminiferous epithelium: light microscopic observations of perfusion-fixed and plastic-embedded testes. Biology of Reproduction. 1990;43:525–542. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod43.3.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraoka Y, Ogawa M, Sakai Y, Takeuchi Y, Komatsu N, Shiozawa M, Tanabe K, Aiso S. PLP-I: a novel prolactin-like gene in rodents. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1999;1447:291–297. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(99)00160-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horseman ND, Zhao W, Montecino-Rodriguez E, Tanaka M, Nakashima K, Engle SJ, Smith F, Markoff E, Dorshkind K. Defective mammopoiesis, but normal hematopoiesis, in mice with a targeted disruption of the prolactin gene. EMBO Journal. 1997;16:6926–6935. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.6926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishibashi K, Imai M. Identification of four new members of the rat prolactin/growth hormone gene family. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1999;262:575–578. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jern P, Coffin JM. Effects of retroviruses on host genome function. Annual Review of Genetics. 2008;42:709–732. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.42.110807.091501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez T, McDermott JP, Sanchez G, Blanco G. Na,K-ATPase α4 isoform is essential for sperm fertility. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2011;108:644–649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016902108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez T, Sánchez G, Wertheimer E, Blanco G. Activity of the Na,K-ATPase α4 isoform is important for membrane potential, intracellular Ca2+, and pH to maintain motility in rat spermatozoa. Reproduction. 2010;139:835–845. doi: 10.1530/REP-09-0495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaessmann H. Origins, evolution, and phenotypic impact of new genes. Genome Research. 2010;20:1313–1326. doi: 10.1101/gr.101386.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane TM, Goodstadt L, Danecek P, White MA, Wong K, Yalcin B, Heger A, Agam A, Slater G, Goodson M, et al. Mouse genomic variation and its effect on phenotypes and gene regulation. Nature. 2011;477:289–294. doi: 10.1038/nature10413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenagy GJ, Trombulak SC. Size and function of mammalian testes in relation to body size. Journal of Mammalogy. 1986;67:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kent LN, Konno T, Soares MJ. Phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase modulation of trophoblast cell differentiation. BMC Developmental Biology. 2010;10:97. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-10-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidwell MG, Lisch DR. Transposable elements, parasitic DNA, and genome evolution. Evolution. 2001;55:1–24. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2001.tb01268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konno T, Graham AR, Rempel LA, Ho-Chen JK, Alam SM, Bu P, Rumi MA, Soares MJ. Subfertility linked to combined luteal insufficiency and uterine progesterone resistance. Endocrinology. 2010;151:4537–4550. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascaro JS, Hackett PD, Rilling JK. Testicular volume is inversely correlated with nurturing-related brain activity in human fathers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 2013;110:15746–15751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305579110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather JP. Establishment and characterization of two distinct testicular epithelial cell lines. Biology of Reproduction. 1980;23:243–252. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod23.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzuk MM, Lamb DJ. The biology of infertility: research advances and clinical challenges. Nature Medicine. 2008;14:1197–1213. doi: 10.1038/nm.f.1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan RI, Wreford NG, O’Donnell L, de Kretser DM, Robertson DM. The endocrine regulation of spermatogenesis: independent roles for testosterone and FSH. Journal of Endocrinology. 1996;148:1–9. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1480001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoto LG, Arregui L, Sanchez NM, Gomendio M, Roldan ERS. Postnatal testicular development in mouse species with different levels of sperm competition. Reproduction. 2012;143:333–346. doi: 10.1530/REP-11-0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoto LG, Magaña C, Tourmente M, Martín-Coello J, Crespo C, Luque-Larena JJ, Gomendio M, Roldan ER. Sperm competition, sperm numbers and sperm quality in muroid rodents. PLOS One. 2011;6:e18173. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno S. Evolution by gene duplication. Springer Verlag; Berlin: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Petkov PM, Cassell MA, Sargent EE, Donnelly CJ, Robinson P, Crew V, Asquith S, Haar RV, Wiles MV. Development of a SNP genotyping panel for genetic monitoring of the laboratory mouse. Genomics. 2004;83:902–911. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman NA, Huhtaniemi IT. Testicular cell lines. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2004;228:53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawn SM, Cross JC. The evolution, regulation, and function of placenta-specific genes. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 2008;24:159–181. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebollo R, Romanish MT, Mager DL. Transposable elements: an abundant and natural source of regulatory sequences for host genes. Annual Review of Genetics. 2012;46:21–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roby KF, Larsen D, Deb S, Soares MJ. Generation and characterization of antipeptide antibodies to rat cytochrome P-450 side-chain cleavage enzyme. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 1991;79:13–20. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(91)90090-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe HM, Trono D. Dynamic control of endogenous retroviruses during development. Virology. 2011;411:273–287. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato S, Yagi S, Arai Y, Hirabayashi K, Hattori N, Iwatani M, Okita K, Ohgane J, Tanaka S, Wakayama T, et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation profile of tissue-dependent and differentially methylated regions (T-DMRs) residing in mouse pluripotent stem cells. Genes to Cells. 2010;15:607–618. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2010.01404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short RV. The testis: the witness of the mating system, the site of mutation and the engine of desire. Acta Paediatrica Supplement. 1997;422:3–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1997.tb18336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons LW, Fitzpatrick JL. Sperm wars and the evolution of male fertility. Reproduction. 2012;144:519–534. doi: 10.1530/REP-12-0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares MJ. The prolactin and growth hormone families: pregnancy-specific hormones/cytokines at the maternal-fetal interface. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 2004;2:51. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-2-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares MJ, Konno T, Alam SMK. The prolactin family: effectors of pregnancy-dependent adaptations. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2007;18:114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley EL, Johnston DS, Fan J, Papadopoulos V, Chen H, Ge RS, Zirkin BR, Jelinsky SA. Stem Leydig cell differentiation: gene expression during development of the adult rat population of Leydig cells. Biology of Reproduction. 2011;85:1161–1166. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.091850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilbrook AJ, Clarke IJ. Negative feedback regulation of the secretion and actions of gonadotropin-releasing hormone in males. Biology of Reproduction. 2001;64:735–742. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod64.3.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toft DJ, Linzer DIH. Prolactin (PRL)-like protein J, a novel member of the PRL/growth hormone family, is exclusively expressed in maternal decidua. Endocrinology. 1999;140:5095–5101. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.11.7138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner LM, Chuong EB, Hoekstra HE. Comparative analysis of testis protein evolution in rodents. Genetics. 2008;179:2075–2089. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.085902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi S, Hirabayashi K, Sato S, Li W, Takahashi Y, Hirakawa T, Wu G, Hattori N, Hattori N, Ohgane J, et al. DNA methylation profile of tissue-dependent and differentially methylated regions (T-DMRs) in mouse promoter regions demonstrating tissue-specific gene expression. Genome Research. 2008;18:1969–1978. doi: 10.1101/gr.074070.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Hao J, He M, Chen M, Li G. Localization and expression patterns of prolactin-like protein-J in mouse testis. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2014;10:255–261. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A and B, transcription start site (TSS) determination was performed using 5′ RACE from decidual (A) and testicular tissue (B). The bolded and underlined atg indicates the translation start codon for Prl3c1-v1 (A) and Prl3c1-v2 (B). C, RT-PCR analysis of Prl3c1-v1 and Prl3c1-v2 transcripts in the testis from fifteen mouse strains. Please note that Prl3c1-v2 transcripts were present in all strains, whereas Prl3c1-v1 transcripts were not detectable. Positive controls for Prl3c1-v1 = decidua from gestation day 7.5; Prl3c1-v2 = adult testis. Gapdh was used as a loading control.

A, Schematic of Prl3c1 genomic locus and composite transposable element (gray and black bars proximal to TSS of Prl3c1-v2) identified by Repeat Masker. CpG sites situated within blue regions (1, 2, 3, 4 and 5) were analyzed for methylation. B, Bisulfite sequencing results were obtained from decidua (n=6), primary Leydig cells (n=6), and liver (n=3). Open and closed circles represent unmethylated and methylated CpG sites, respectively.

A, Schematic of Prl3c1 genomic locus, composite transposable element, and CpG sites (CG 1–8). CpG sites situated in regions (3 and 4) located within the composite transposable element were analyzed for methylation. B, Results of direct bisulfite sequencing indicate CpG sites (2, 3, 4, 6 and 7) were hypomethylated in Leydig cells (n=6) and hypermethylated in decidua (n=7) and liver (n=6).

A, Schematic of Prl3c1 genomic locus, composite transposable elements, and CpG sites (red arrows). CpG sites situated in blue regions (3 and 5) within the composite transposable elements were analyzed for methylation. B, MultiNA-COBRA results indicate CpG sites (3 and 5) were hypomethylated in Leydig cells (n=6) but hypermethylated in decidua (n=7) and liver (n=6).

A, FLAG-tagged PLP-J V2 was ectopically expressed in COS7 cells. Subcellular fractioned proteins were analyzed by western blotting with anti-FLAG antibodies (Cyto: cytoplasm; Nu: nucleus). Western blotting for GAPDH and HISTONE H3 were used to monitor the integrity of the cytoplasmic and nuclear preparations, respectively. COS7 cells transfected with an empty vector were used as a control. B–D, Effects of ectopic expression of empty vector or Prl3c1-v2 on TM3 (B), MA-10 (C), and COS7 (D) cell numbers following 72 h of culture. **P<0.001 compared to empty vector control.

A, qRT-PCR analysis of progenitor Leydig cell transcript expression in MLTC-1 (open bars) and TM3 (filled bars) Leydig cells. MLTC-1 Leydig cell Hsd3b1 and Hsd3b6 transcript responses to ectopic Prl3c1-v2 expression (B) and LH treatment (C). D, MLTC-1 Leydig cell Akr1c14, Pmp22, and Ptma (Leydig progenitor cell-associated) transcript responses to ectopic Prl3c1-v2 expression. TM3 Leydig cell Hsd3b1 and Hsd3b6 transcript responses to ectopic Prl3c1-v2 expression (E) and LH treatment (F). G, TM3 Leydig cell Akr1c14, Pmp22, and Ptma (Leydig progenitor cell-associated) transcript responses to ectopic Prl3c1-v2 expression. *P<0.05, **P<0.001.