Abstract

A form of α-galactosylceramide, KRN7000, activates CD1d-restricted Vα14-invariant (Vα14i) natural killer (NK) T cells and initiates multiple downstream immune reactions. We report that substituting the C26:0 N-acyl chain of KRN7000 with shorter, unsaturated fatty acids modifies the outcome of Vα14i NKT cell activation. One analogue containing a diunsaturated C20 fatty acid (C20:2) potently induced a T helper type 2-biased cytokine response, with diminished IFN-γ production and reduced Vα14i NKT cell expansion. C20:2 also exhibited less stringent requirements for loading onto CD1d than KRN7000, suggesting a mechanism for the immunomodulatory properties of this lipid. The differential cellular response elicited by this class of Vα14i NKT cell agonists may prove to be useful in immunotherapeutic applications.

Keywords: cytokines, inflammation, autoimmunity, immunoregulation

Natural killer (NK) T cells were defined originally as lymphocytes coexpressing T cell receptors (TCRs) and C-type lectin receptors characteristic of NK cells. A major subset of NKT cells recognizes the MHC class I-like molecule CD1d by using TCRs composed of an invariant TCR-α chain (mouse Vα14-Jα18, human Vα24-Jα18) paired with TCR-β chains with markedly skewed Vβ usage (1). These CD1d-restricted Vα14-invariant (Vα14i) NKT cells are highly conserved in phenotype and function between mice and humans (2). Vα14i NKT cells influence various immune responses and play an important role in regulating autoimmunity (3, 4). One example is the nonobese diabetic mouse. When compared with normal mice, nonobese diabetic mice have fewer Vα14i NKT cells, which are defective in their capacity to produce antiinflammatory cytokines like IL-4 (5, 6). Deficiencies in NKT cells have also been observed in humans with various autoimmune diseases (7, 8).

Vα14i NKT cells have been manipulated to prevent or treat autoimmune disease, mostly through the use of KRN7000, a synthetic α-galactosylceramide (α-GalCer, Fig. 1A) that binds to the hydrophobic groove of CD1d and then activates Vα14i NKT cells by means of TCR recognition (9). KRN7000 treatment of nonobese diabetic mice blocks development of T helper (TH) type 1-mediated autoimmune destruction of pancreatic islet β-cells, thus delaying or preventing disease (10–12). There has been considerable interest in methods that would allow a more selective activation of these cells. In particular, the ability to trigger IL-4 production without eliciting strong IFN-γ or other proinflammatory cytokines may reinforce the immunoregulatory functions of Vα14i NKT cells. This effect is detected after Vα14i NKT cell activation with a glycolipid designated OCH, which is an α-GalCer analogue that is structurally distinct from KRN7000 in having a substantially shorter sphingosine chain and functionally by its preferential induction of IL-4 secretion (13, 14).

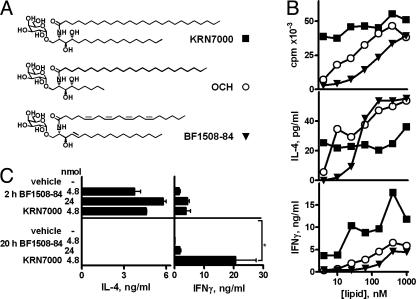

Fig. 1.

Induction of a TH2-polarized cytokine response by an unsaturated analogue of α-GalCer. (A) Glycolipid structures. (B) [3H]thymidine incorporation and supernatant IL-4 and IFN-γ levels in 72-h splenocyte cultures with graded amounts of glycolipid. Means from triplicate cultures are shown; SEMs were typically <10% of the mean. (C) Serum IL-4 and IFN-γ levels (at 2 and 20 h) of C57BL/6 mice injected i.p. with 4.8 or 24 nmol of glycolipid. KRN7000 was the only glycolipid that induced significant IFN-γ levels at 20 h (*, P < 0.05, Kruskall–Wallis test, Dunn's posttest). Means ± SD of two or three mice per group are shown.

In this study, we investigated responses to α-GalCer analogues produced by alteration of the length and extent of unsaturation of their N-acyl substituents. Such modifications altered the outcome of Vα14i NKT cell activation and, in some cases, led to a TH2-biased and potentially antiinflammatory cytokine response. This change in the NKT cell response was likely the result of an alteration of downstream steps in the cascade of events triggered by Vα14i NKT cell activation, including the reduction of secondary activation of IFN-γ-producing NK cells. These findings point to a class of Vα14i NKT cell agonists that may have superior properties for the treatment of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases.

Materials and Methods

Mice and Cell Lines. C57BL/6 mice (8- to 15-wk-old females) were obtained either from The Jackson Laboratory or Taconic Farms. CD1d-/- mice were provided by M. Exley and S. Balk (Beth Israel–Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston) (15). Vα14i NKT cell-deficient Jα18-/- mice were a gift from M. Taniguchi and T. Nakayama (Chiba University, Chiba, Japan) (16). Both knockout mice were in the C57BL/6 background. Animals were kept in specific pathogen-free housing. The protocols that we used were in accordance with approved institutional guidelines.

Mouse CD1d-transfected RMA-S cells (RMA-S.mCD1d) were provided by S. Behar (Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School) (17). WT or cytoplasmic tail-deleted CD1d-transfected A20 cells and the Vα14i NKT hybridoma DN3A4–1.2 were provided by M. Kronenberg (La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology, La Jolla, CA) (18, 19). Hybridoma DN32D3 was a gift from A. Bendelac (University of Chicago, Chicago) (1). Cells were cultured in RPMI medium 1640 (GIBCO) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS (Gemini Biological Products, Calabasas, CA)/10 mM Hepes/2 mM l-glutamine/0.1 mM nonessential amino acids/55 μM 2-mercaptoethanol/100 units/ml penicillin/100 μg/ml streptomycin (GIBCO) in a 37°C humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

Glycolipids. BF1508-84 was synthesized by Biomira (Edmonton, Canada). OCH [(2S, 3S, 4R)-1-O-(α-d-galactopyranosyl)-N-tetracosanoyl-2 amino-1,3,4-nonanetriol] was synthesized as described (13). An overview of the methods for synthesis of KRN7000 [(2S, 3S, 4R)-1-O-(α-d-galactopyranosyl)-N-hexacosanoyl-2-amino-1,3,4-octadecanetriol] and other N-acyl analogues used in this study is shown in Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site. Lipids were dissolved in chloroform/methanol (2:1 ratio) and stored at -20°C. Aliquots from this stock were dried and reconstituted to either 100 μM in DMSO for in vitro work or to 500 μM in 0.5% Tween-20 in PBS for in vivo studies.

In Vitro Stimulations. Bulk splenocytes were plated at 300,000 cells per well in 96-well flat-bottom tissue culture plates with glycolipid diluted in 200 μl of medium. After 48 or 72 h at 37°C, 150 μl of supernatant was removed for cytokine measurements, and 0.5 μCi (1 Ci = 37 GBq) [3H]thymidine per well (specific activity 2 Ci/mmol; PerkinElmer) was added for an 18-h pulse. Proliferation was estimated by harvesting cells onto 96-well filter mats and counting β-scintillations with a 1450 Microbeta Trilux (Wallac, Gaithersburg, MD; PerkinElmer).

Supernatant levels of IL-2, IL-4, IL-12p70, and IFN-γ were measured by ELISA using capture and biotinylated detection antibody pairs (BD PharMingen) and streptavidin–horseradish peroxidase (Zymed) with TMB-Turbo substrate (Pierce) or streptavidin–alkaline phosphatase (Zymed) with 4-nitrophenyl phosphate substrate (Sigma). IL-2 standard was obtained from R & D Systems; IL-4, IL-12p70 and IFN-γ were obtained from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ).

Hybridoma Stimulations. CD1d+ RMA-S or A20 cells (50,000 cells in 100 μl per well) were pulsed with graded doses of glycolipid for 6 h at 37°C. After three washes in PBS, Vα14i NKT hybridoma cells (50,000 cells in 100 μl) were added for 12 h. Supernatant IL-2 was assayed by ELISA. Alternatively, CD1d-transfected cells (RMA-S.mCD1d) were lightly fixed either before or after exposure to antigen (20). Cells were washed twice in PBS and then fixed in 0.05% glutaraldehyde (grade I, Sigma) in PBS for 30 s at room temperature. Fixative was quenched by addition of 0.2 M l-lysine (pH 7.4) for 2 min, followed by two washes with medium before addition of responders.

For cell-free presentation, recombinant mouse CD1d (1 μg/ml in PBS) purified from a baculovirus expression system (21) was adhered to tissue culture plates for 1 h at 37°C. After the washing off of unbound protein, glycolipids were then added at varying concentrations for 1 h at 37°C. Lipids were added in a 150 mM NaCl/10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7) with or without 0.025% Triton X-100. Wells were washed before addition of hybridoma cells.

In Vivo Studies. Mice were given i.p. injections of 4.8 nmol of glycolipid in 0.2 ml of PBS plus 0.025% Tween-20 or vehicle alone. Sera were collected and tested for IL-4, IL-12p70, and IFN-γ, as described above. Alternatively, mice were killed at various times for FACS analysis.

Flow Cytometry. Splenocytes or thymocytes were isolated and used without further purification. Nonspecific staining was blocked by using FACS buffer (0.1% BSA/0.05% NaN3 in PBS) with 10 μg/ml rat anti-mouse CD16/32 (2.4G2; The American Type Culture Collection). Cells (≤106) were stained with phycoerythrin or allophycocyanin-conjugated glycolipid/mouse CD1d tetramers (21) for 30–90 min at room temperature and then with fluorescently labeled antibodies (from Caltag, South San Francisco, CA, or PharMingen) for 30 min at 4°C. Data were acquired on either a FACSCalibur or LSR-II flow cytometer (Becton Dickenson) and analyzed by using winmdi 2.8 (Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA). For some experiments, dead cells were excluded by using propidium iodide (Sigma) or 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Roche).

FACS-based cytokine secretion assays (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) were used to quantitatively detect single-cell production of IL-4 or IFN-γ. Splenocytes were aseptically collected from mice that were previously injected i.p. with glycolipid analogues and not subjected to further stimulation. When applicable, 106 cells were prestained with labeled tetramer for 30 min at room temperature and then washed in PBS plus 0.1% BSA. Cells were then stained with the cytokine catch reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions, followed by incubation with rotation in 2 ml of medium at 37°C for 45 min. Cells were then washed, stained with fluorescently labeled antibodies to cell-surface antigens, phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-IFN-γ or IL-4, and propidium iodide, as described above.

Results

TH2-Skewing Properties of an α-GalCer Analogue. During screening of a panel of synthetic glycosyl ceramides, we identified a compound that showed TH2-skewing of the cytokine profile generated by Vα14i NKT cell activation. Glycolipid BF1508-84 differed structurally from both OCH and KRN7000 by having a shortened, unsaturated fatty-acid chain (C20:4 arachidonate) and a double bond in place of the 4-hydroxy in the sphingosine base (Fig. 1 A). Despite these modifications, BF1508-84 activated proliferation and cytokine secretion by mouse splenocytes (Fig. 1B). These responses were Vα14i NKT cell-dependent, as demonstrated by their absence in both CD1d-/- and Jα18-/- mice (data not shown). Maximal proliferation and IL-4 levels were comparable with those obtained with KRN7000 and OCH, although a higher concentration of BF1508-84 was required to reach similar responses. Interestingly, IFN-γ secretion stimulated by BF1508-84, even at higher tested concentrations, did not reach the levels seen with KRN7000. This profile of cytokine responses suggested that BF1508-84 can elicit a TH2-biased Vα14i NKT cell-dependent cytokine production, similar to OCH (13).

We measured serum cytokine levels at various times after a single injection of either KRN7000 or BF1508-84 into C57BL/6 mice. Our studies confirm published reports that a single i.p. injection of KRN7000 leads to a rapid 2-h peak of serum IL-4 (Fig. 1C and data not shown). However, IFN-γ levels were relatively low at 2 h but rose to a plateau at 12–24 h (13, 22). With BF1508-84, production of IL-4 at 2 h was preserved, whereas IFN-γ was barely detectable at 20 h (Fig. 1C). This pattern was identical to that reported for OCH (13, 22) and was not due to the lower potency of BF1508-84 because a 5-fold greater dose did not change the TH2-biased cytokine profile (Fig. 1C).

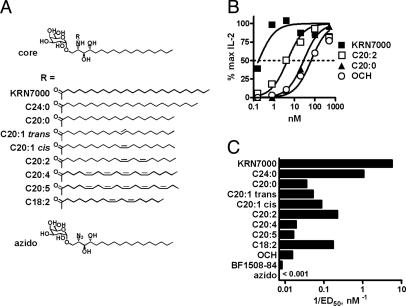

Systematic Variation of Fatty-Acyl Unsaturation in α-GalCer. The cytokine response to BF1508-84 suggested that altering the fatty-acid length and unsaturation of α-GalCer could provide an effective strategy for creating Vα14i NKT cell activators with modified functional properties. We used a synthetic approach (Fig. 7, and G.S.B. and P.A.I., unpublished data) to generate lipids in which 20-carbon acyl chains with varying degrees of unsaturation were coupled onto the α-galactosylated sphingosine core structure (Fig. 2A). These compounds were first screened for the ability to activate a canonical Vα14-Jα18/Vβ8.2+, CD1d-restricted NKT cell hybridoma cocultured with CD1d+ antigen-presenting cells. Hybridoma DN3A4–1.2 recognized all C20 analogues of α-GalCer with various potencies when presented by CD1d-transfected RMA-S cells, and it failed to recognize an azido-substituted analogue lacking a fatty-acid chain (Fig. 2 B and C). As reported (9), mere shortening of the fatty-acid chain affected Vα14i NKT cell recognition, and reduction of saturated fatty-acid length from C26 to C20 was associated with a ≈2 log decrease in potency. However, insertion of double bonds into the C20 acyl chain augmented stimulatory activity. One lipid in particular, with unsaturations at carbons 11 and 14 (C20:2), was more potent than other analogues in the panel. This increase in potency seemed to be a direct result of the two double bonds, because an independently synthesized analogue with a slightly shorter diunsaturated acyl chain (C18:2) showed a potency similar to that of C20:2 (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Recognition of a panel of unsaturated analogues of KRN7000 by a canonical Vα14i NKT hybridoma. (A) Analogue structures. (B) Dose–response curves showing IL-2 production by hybridoma DN3A4–1.2 after stimulation with RMA-S.mCD1d cells pulsed with various doses of glycolipid. Maximal IL-2 concentrations in each assay were designated as 100%. Four-parameter logistic equation dose–response curves are shown; the dotted line denotes the half-maximal dose. (C) Relative potencies of the analogue panel in Vα14i NKT cell recognition, plotted as the reciprocal of the effective dose required to elicit a half-maximal response (1/ED50). Similar results were obtained by using another Vα14i NKT hybridoma, DN32D3.

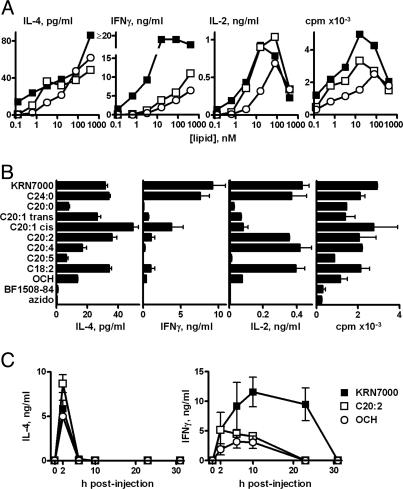

We also studied in vitro splenocyte cytokine polarization resulting from Vα14i NKT cell stimulation by each lipid in the panel. Supernatant IL-4, IFN-γ, and IL-2 levels were measured over a wide range of glycolipid concentrations. All C20 variants induced IL-4 production comparable with that of KRN7000 (Fig. 3 A and B, and data not shown). However, IFN-γ levels for all but one C20 analogue (C20:1 cis) were markedly reduced to one-fourth of the maximal levels observed with KRN7000 and the closely related C24:0 analogue, or less. In addition, C20:1-cis, C20:2, and C18:2 were unique in this class of compounds in inducing strong IL-2 production and cellular proliferation similar to that seen with KRN7000 and C24:0 yet with much lower IFN-γ induction. This in vitro TH2-bias was also evident in vivo. Mice given C20:2 and C20:4 showed systemic cytokine production that resembled stimulation by OCH or BF1508-84. Thus, a rapid burst of serum IL-4 was observed without the delayed and sustained production of IFN-γ typical of KRN7000 (Fig. 3C and data not shown). No significant difference between the glycolipids was seen in serum IL-12p70 levels at 6 h after treatment (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

TH2-skewing of in vitro and in vivo cytokine responses to C20:2. (A) Dose–response curves reporting 48 h IL-4, IFN-γ, or IL-2 production, and cell proliferation of splenocytes in response to KRN7000, C20:2, and OCH. Means of duplicate cultures are shown; SEM were <10% of the means. (B) Cytokine and proliferation measurements on splenocytes exposed to a submaximal dose (3.2 nM) of the panel of α-GalCer analogues shown in Fig. 2. Mean ± SEM from duplicate cultures shown. (C) Serum IL-4 and IFN-γ levels in mice given 4.8 nmol of KRN7000, C20:2, or OCH. Mean ± SD of two or three mice are shown. Vehicle-treated mice had cytokine levels below limits of detection. The results shown are representative of two or more experiments.

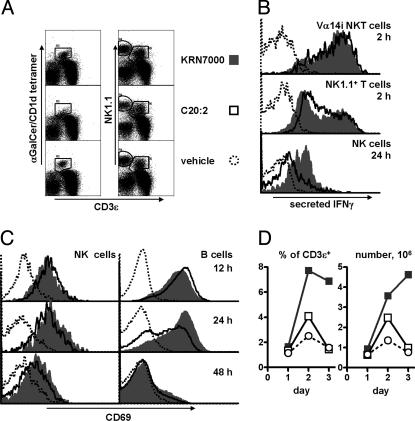

Identification of Cytokine-Producing Cells in Vivo. Previous reports (23–25) established that Vα14i NKT cells are a predominant source of IL-4 and IFN-γ in the early (2 h) response to KRN7000 and that by 6 h after injection these cells become progressively undetectable because of receptor down-modulation, whereas secondarily activated NK cells begin to actively produce IFN-γ. Gating on either α-GalCer-loaded CD1d tetramer+ or NK1.1+ T cells, we observed similar strong cytokine secretion for both IL-4 (data not shown) and IFN-γ in Vα14i NKT cells at 2 h after injection of KRN7000 or C20:2 (Fig. 4 A and B). We concluded that cytokine polarization observed after C20:2 administration was not due to differences in the initial Vα14i NKT cell response but, rather, reflected altered downstream events such as the relatively late IFN-γ production by activated NK cells.

Fig. 4.

Sequelae of KRN7000 and C20:2-induced Vα14i NKT cell activation. (A)Vα14i NKT cell (tetramer+ CD3εint), NK cell (NK1.1+ CD3ε-), and NK1.1+ T cell (NK1.1int CD3εint) identification by FACS in splenocytes from mice given KRN7000, C20:2, or vehicle i.p. 2 h earlier. Lymphocytes gated as negative for B220 and propidium iodide are shown. (B) Histogram profiles for IFN-γ secretion of splenic Vα14i NKT, NK1.1+ T, or NK cells from mice 2 or 24 h after treatment with glycolipid. IFN-γ-staining in C24:0-stimulated samples was identical to that of KRN7000-stimulated samples. (C) CD69 levels of splenic NK cells (gated as CD3ε- NK1.1+) or B cells (CD3ε- NK1.1- B220+) at 12, 24, or 48 h after injection of glycolipid. (D) Splenic Vα14i NKT cell (B220- CD3εint tetramer+) frequency, measured as either percentages of T cells or as total NKT cell number, in mice 1, 2, or 3 days after glycolipid administration. The results shown are representative of three independent experiments.

Secreted cytokine staining confirmed that in both KRN7000- and C20:2-treated mice, NK cells were IFN-γ+ at 6–12 h after treatment (26, 27). However, whereas splenic NK cells from mice that received either KRN7000 or the closely related C24:0 analogue strongly produced IFN-γ as late as 24 h after initial activation, NK cells from C20:2-treated mice showed substantially reduced staining (Fig. 4B). Together, these results pointed to a less sustained secondary IFN-γ production by NK cells (rather than a change in the initial cytokine response of Vα14i NKT cells) as the major factor responsible for the TH2 bias of the systemic cytokine response to C20:2.

Sequelae of Vα14i NKT Cell Activation by C20:2. Secondary activation of bystander B and NK cells after KRN7000 administration has been studied by using expression of the activation marker CD69 (26, 28–30). We followed CD69 expression of splenic NK and B cell populations for several hours after KRN7000 or C20:2 administration. Both populations began to up-regulate CD69 at 4–6 h after injection (data not shown). Paradoxically, C20:2 induced slightly higher CD69 levels on both cell populations up until 12 h, although this trend was reversed from 24 h onwards, suggesting an earlier up-regulation yet faster subsequent downregulation of the marker (Fig. 4C). NK cell forward scatter likewise remained higher in KRN7000-treated mice at days 1–3 compared with C20:2-treated mice (data not shown).

It is established that Vα14i NKT cells expand beyond homeostatic levels 2 or 3 days after KRN7000 stimulation (24, 25). In our study, a 3- to 5-fold expansion in splenic Vα14i NKT cell number occurred in KRN7000-treated mice at day 3 after injection. Interestingly, after in vivo administration of C20:2, only a minimal transient expansion was observed on day 2, with no expansion of the Vα14i NKT cell population thereafter, even as late as day 5 (Fig. 4D and data not shown). Together, our findings indicated pronounced alterations in the late sequelae of Vα14i NKT cell activation with the C20:2 analogue compared with KRN7000.

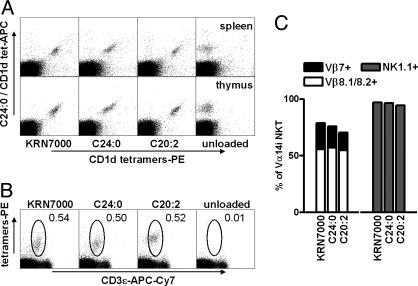

Recognition of KRN7000 and C20:2 by Identical Cell Populations. CD1d complexes containing the α-GalCer analogue OCH have been shown to have significantly reduced avidity for TCRs of Vα14i NKT cells compared with binding of KRN7000-loaded complexes (31). This finding suggests the possibility that the TH2-biased response of C20:2 could be a result of preferential stimulation of Vα14i NKT cell subsets with TCRs of higher affinity for lipid-loaded CD1d. In fact, phenotypically defined subsets of murine and human NKT cells have been described that show a bias toward increased production of IL-4 relative to IFN-γ upon stimulation (32–36). However, by costaining of splenic and thymic Vα14i NKT cells by using CD1d tetramers loaded with different lipids, we demonstrated that identical populations recognized C24:0, C20:2, and KRN7000 (Fig. 5A). Single staining with these reagents revealed no difference in Vβ usage or NK1.1 status of cells reactive with the different analogue tetramers (Fig. 5 B and C). Interestingly, C20:2-loaded tetramers stained NKT cells more strongly than tetramers loaded with KRN7000, reflecting a slightly higher affinity of the C20:2–CD1d complex to the Vα14i TCR (J.S.I. and S.A.P., unpublished results). Together, these findings demonstrated that the altered cytokine response to C20:2 cannot be the result of preferential activation of a subset of Vα14i NKT cells.

Fig. 5.

Recognition of KRN7000, C24:0, and C20:2 by the same population of Vα14i NKT cells. (A) Costaining of C57BL/6 splenocytes or thymocytes with allophycocyanin-conjugated CD1d tetramers assembled with C24:0, and phycoerythrin-labeled CD1d tetramers assembled with various analogues. (B) Thymocytes were stained with C24:0, C20:2, KRN7000, or vehicle-loaded CD1d tetramers–phycoerythrin, and with antibodies to B220, CD3ε,Vβ7, Vβ8.1/8.2, or NK1.1. Dot plots show gating for tetramer+ T cells, after exclusion of B lymphocytes, and dead cells. (C) TCR Vβ and NK1.1 phenotype of tetramer+ CD3εint thymocytes. Analogous results were obtained with splenocytes. The results shown are representative of three or more experiments.

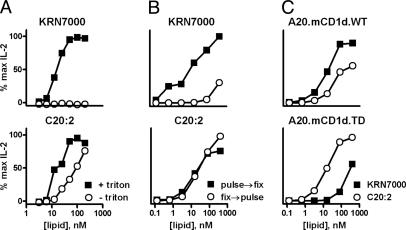

Loading Requirements of α-GalCer Analogues onto CD1d. To find an alternative explanation for the TH2-biased response to C20:2, we studied requirements for handling of different forms of α-Gal-Cer by antigen-presenting cells. We employed a cell-free system in which platebound mouse CD1d was loaded with doses of KRN7000 or C20:2 in the presence or absence of the detergent Triton X-100 (37). By using IL-2 production by DN3A4–1.2 as a readout for glycolipid loading of CD1d, we observed a marked dependence on detergent for loading of KRN7000 but not for C20:2 (Fig. 6A). This result suggested a significant difference in requirement for cofactors, such as acidic pH or lipid transfer proteins, that facilitate lipid loading onto CD1d in endosomes (38–41). We assessed this hypothesis further by using glutaraldehyde fixation of CD1d+ antigen-presenting cells, which blocks antigen uptake and recycling of CD1d between endosomes and the plasma membrane. Vα14i NKT cell recognition of KRN7000 was markedly reduced if lipid loading was done after fixation of RMA-S.mCD1d cells, whereas recognition of C20:2 was unimpaired (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Differential requirements for CD1d loading with KRN7000 and C20:2. IL-2 response of hybridoma DN3A4–1.2 to glycolipid presentation in three in vitro CD1d presentation systems: platebound CD1d loaded with varying amounts of KRN7000 or C20:2 in the presence or absence of the detergent Triton X-100 (A), RMA-S.CD1d cells pulsed with glycolipid before or after glutaraldehyde fixation (B), or WT or cytoplasmic tail-deleted (TD) CD1d-transfected A20 cells, loaded with either KRN7000 or C20:2 (C).

Similar conclusions were drawn from experiments by using A20 cells transfected with either WT or cytoplasmic tail-deleted CD1d (Fig. 6C). The tail-deleted CD1d mutant lacks the intracellular tyrosine-based sorting motif required for internalization and endosomal localization of CD1d (19). As was the case with RMA-S.mCD1d, WT CD1d-transfected A20 cells presented KRN7000 more potently than C20:2. However, the tail-deleted mutant presented C20:2 with at least 20-fold greater efficiency than KRN7000. Together, these results point to the conclusion that the TH2-skewing C20:2 analogue had substantially less dependence on endosomal loading for presentation by CD1d when compared with compounds that produced a more mixed response with strong IFN-γ production, such as KRN7000.

Discussion

This study details in vitro and in vivo consequences of activation of Vα14i NKT cells with C20:2, a diunsaturated N-acyl substituted analogue of the prototypical α-GalCer, KRN7000. The TH2 cytokine bias observed with C20:2 is not unique: OCH and other shortened fully saturated lipids have been shown to have this effect (13, 42). C20:2 differs from these other compounds in two potentially important respects. First, the in vitro potency of C20:2 for stimulation of certain Vα14i NKT cell functions (e.g., proliferation and secretion of IL-4 and IL-2) approaches that of KRN7000, whereas OCH appears to be a much weaker Vα14i NKT cell agonist. Second, staining with C20:2-loaded CD1d tetramers, as opposed to OCH, is undiminished compared with KRN7000. This finding would suggest that, as a therapeutic agent, C20:2 will be recognized by the identical global Vα14i NKT cell population (as KRN7000 is) and not limited to higher-affinity NKT cell subsets, as suggested for OCH (31).

A recent study showed that one mechanism by which OCH may induce a TH2-biased cytokine response involves changes in IFN-γ production by Vα14i NKT cells themselves. Oki et al. (43) reported that the transcription factor gene c-Rel, a member of the NF-κB family of transcriptional regulators that is a crucial component of IFN-γ production, is inducibly transcribed in KRN7000-stimulated but not OCH-stimulated Vα14i NKT cells. Although we have not assessed c-Rel induction or other factors involved in IFN-γ production in response to C20:2, our findings did not suggest that early IFN-γ production by Vα14i NKT cells was different after activation with C20:2 versus KRN7000. Both lipids induced identical single-cell IFN-γ staining in Vα14i NKT cells and serum IFN-γ levels at 2 h after injection. However, in contrast to the apparent similarity in Vα14i NKT cells, NK cell IFN-γ production was significantly reduced and less sustained after in vivo administration of C20:2 compared with KRN7000. Hence, failure of C20:2 to fully activate downstream events leading to optimal NK cell secondary stimulation by activated Vα14i NKT cells appears to be the most likely mechanism by which C20:2 induces reduced IFN-γ and an apparent TH2-biased systemic response.

C20:2 administration resulted also in a more rapid but less sustained CD69 up-regulation in NK and B cells, as well as a lack of a substantial Vα14i NKT cell expansion. These findings were surprising, given that TCR down-modulation observed on Vα14i NKT cells within the first few hours after C20:2 stimulation was similar to or greater than that induced by KRN7000 (Fig. 4A and data not shown), indicating strong TCR signaling in response to the analogue. These features of the response to C20:2 may be a further reflection of the failure of C20:2 to induce a full range of downstream events after Vα14i NKT cell activation, including the production of cytokines or other factors required to support the expansion of Vα14i NKT cells.

What mechanism can then be invoked to account for the altered cytokine response to C20:2 and other N-acyl variants of KRN7000? One intriguing possibility is provided by our analysis of requirements for presentation of C20:2 compared with KRN7000, which revealed marked differences between these glycolipids in their need for endosomal loading onto CD1d. CD1d and other CD1 proteins undergo transport into the endocytic pathway, leading to intracellular loading with lipid antigens and subsequent recycling to the cell surface (39). The importance of endosomal loading for KRN7000 most likely reflects the impact of factors in these compartments that facilitate the insertion of lipids into the CD1d ligand-binding groove. These factors include the acidic pH of the endosomal environment, as well as lipid transport proteins, such as saposins and GM2 activator protein (38, 40, 41). Our findings indicate that C20:2 can efficiently load onto CD1d in the absence of these endosomal cofactors. Consequently, we speculate that C20:2 may be strongly presented by any cell type that expresses surface CD1d, regardless of its ability to efficiently endocytose lipids from the extracellular space. This more widespread presentation could lead to a more pronounced presentation of C20:2 by nonprofessional antigen-presenting cell types compared with KRN7000. Because many cell types express CD1d, including all hematopoietic lineages and various types of epithelia (44–48), presentation of C20:2 by nonprofessional antigen-presenting cells may explain the more rapid trans-activation of bystander cells observed with C20:2. An alternative hypothesis is that the endosomal loading requirements of KRN7000 result in its preferential localization into CD1d molecules contained in membrane lipid rafts, whereas the permissive loading properties of C20:2 would result in a more uniform glycolipid distribution across the cell membrane. Evidence of lipid raft localization of CD1d and raft influence on the TH-bias of MHC class II-restricted CD4+ T cells lend support to this model (49, 50). Either scenario would be expected to result in decreased delivery of costimulatory signals associated with professional antigen-presenting cells (e.g., dendritic cells) and, thus, lead to quantitative and qualitative differences in the outcome of Vα14i NKT cell stimulation. Consistent with both models, Vα14i NKT cell activation with KRN7000 in vitro in the presence of costimulatory blockade (anti-CD86) can polarize cytokine production to a TH2 profile (22).

We have shown that structurally modified forms of α-GalCer with alterations in their N-acyl substituents can be designed to generate potent immunomodulators that stimulate qualitatively altered responses from Vα14i NKT cells. Our results confirm and extend several basic observations and principles established from earlier studies on less potent agonists, such as OCH. Further study of these and similar analogues may yield compounds with clear advantages for treatment or prevention of specific immunologic disorders or for the stimulation of protective host immunity against particular pathogens.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Koganty and S. Gandhi (Biomira) for sharing their panel of synthetic glycosylceramides, which included compound BF1508-84; M. Kronenberg for the recombinant baculovirus used for production of soluble mouse CD1d; M. Taniguchi, T. Nakayama, A. Bendelac, M. Exley, S. Balk, S. Behar, and M. Kronenberg for gifts of mice and cell lines; Z. Hu for expert technical assistance; and T. DiLorenzo for critical reading of this manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AI45889, AI48933, and DK068690 (to S.A.P.), the Japan Human Sciences Foundation (T.Y. and S.A.P.), the Pharmaceutical and Medical Devices Agency (T.Y.), Medical Research Council Grants G9901077 and G0000895 (to G.S.B.), and Wellcome Trust Grants 060750 and 072021 (to G.S.B.). G.S.B. is a Lister Jenner Research Fellow.

Author contributions: K.O.A.Y., J.S.I., A.M., Y.D., P.A.I., Y.-T.C., G.S.B., and S.A.P. designed research; K.O.A.Y., J.S.I., A.M., Y.D., P.A.I., C.F., I.A., N.F., and Y.-T.C. performed research; K.O.A.Y., J.S.I., A.M., Y.D., P.A.I., Y.-T.C., G.S.B., and S.A.P. analyzed data; and K.O.A.Y., G.S.B., and S.A.P. wrote the paper.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: Vα14i, Vα14 invariant; NK, natural killer; α-GalCer, α-galactosylceramide; TH, T helper; TCR, T cell receptor; RMA-S.mCD1d, mouse CD1d-transfected RMA-S cells.

References

- 1.Lantz, O. & Bendelac, A. (1994) J. Exp. Med. 180, 1097-1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brossay, L. & Kronenberg, M. (1999) Immunogenetics 50, 146-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Godfrey, D. I., Hammond, K. J., Poulton, L. D., Smyth, M. J. & Baxter, A. G. (2000) Immunol. Today 21, 573-583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson, S. B. & Delovitch, T. L. (2003) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3, 211-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poulton, L. D., Smyth, M. J., Hawke, C. G., Silveira, P., Shepherd, D., Naidenko, O. V., Godfrey, D. I. & Baxter, A. G. (2001) Int. Immunol. 13, 887-896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gombert, J.-M., Tancrede-Bohin, T., Hameg, A., do Carmo Leite-de-Moraes, M., Vicari, A. P., Bach, J.-F. & Herbelin, A. (1996) Int. Immunol. 8, 1751-1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Der Vliet, H. J., Von Blomberg, B. M., Nishi, N., Reijm, M., Voskuyl, A. E., van Bodegraven, A. A., Polman, C. H., Rustemeyer, T., Lips, P., Van Den Eertwegh, A. J., et al. (2001) Clin. Immunol. 100, 144-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taniguchi, M., Harada, M., Kojo, S., Nakayama, T. & Wakao, H. (2003) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21, 483-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawano, T., Cui, J., Koezuka, Y., Toura, I., Kaneko, Y., Motoki, K., Ueno, H., Nakagawa, R., Sato, H., Kondo, E., et al. (1997) Science 278, 1626-1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang, B., Geng, Y. B. & Wang, C. R. (2001) J. Exp. Med. 194, 313-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharif, S., Arreaza, G. A., Zucker, P., Mi, Q. S., Sondhi, J., Naidenko, O. V., Kronenberg, M., Koezuka, Y., Delovitch, T. L., Gombert, J. M., et al. (2001) Nat. Med. 7, 1057-1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong, S., Wilson, M. T., Serizawa, I., Wu, L., Singh, N., Naidenko, O. V., Miura, T., Haba, T., Scherer, D. C., Wei, J., et al. (2001) Nat. Med. 7, 1052-1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyamoto, K., Miyake, S. & Yamamura, T. (2001) Nature 413, 531-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizuno, M., Masumura, M., Tomi, C., Chiba, A., Oki, S., Yamamura, T. & Miyake, S. (2004) J. Autoimmun. 23, 293-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sonoda, K. H., Exley, M., Snapper, S., Balk, S. P. & Stein-Streilein, J. (1999) J. Exp. Med. 190, 1215-1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cui, J., Shin, T., Kawano, T., Sato, H., Kondo, E., Toura, I., Kaneko, Y., Koseki, H., Kanno, M. & Taniguchi, M. (1997) Science 278, 1623-1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Behar, S. M., Podrebarac, T. A., Roy, C. J., Wang, C. R. & Brenner, M. B. (1999) J. Immunol. 162, 161-167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brossay, L., Tangri, S., Bix, M., Cardell, S., Locksley, R. & Kronenberg, M. (1998) J. Immunol. 160, 3681-3688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prigozy, T. I., Naidenko, O., Qasba, P., Elewaut, D., Brossay, L., Khurana, A., Natori, T., Koezuka, Y., Kulkarni, A. & Kronenberg, M. (2001) Science 291, 664-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Porcelli, S., Morita, C. T. & Brenner, M. B. (1992) Nature 360, 593-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsuda, J. L., Naidenko, O. V., Gapin, L., Nakayama, T., Taniguchi, M., Wang, C. R., Koezuka, Y. & Kronenberg, M. (2000) J. Exp. Med. 192, 741-754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pal, E., Tabira, T., Kawano, T., Taniguchi, M., Miyake, S. & Yamamura, T. (2001) J. Immunol. 166, 662-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuda, J. L., Gapin, L., Baron, J. L., Sidobre, S., Stetson, D. B., Mohrs, M., Locksley, R. M. & Kronenberg, M. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 8395-8400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crowe, N. Y., Uldrich, A. P., Kyparissoudis, K., Hammond, K. J., Hayakawa, Y., Sidobre, S., Keating, R., Kronenberg, M., Smyth, M. J. & Godfrey, D. I. (2003) J. Immunol. 171, 4020-4027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson, M. T., Johansson, C., Olivares-Villagomez, D., Singh, A. K., Stanic, A. K., Wang, C. R., Joyce, S., Wick, M. J. & Van Kaer, L. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 10913-10918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carnaud, C., Lee, D., Donnars, O., Park, S. H., Beavis, A., Koezuka, Y. & Bendelac, A. (1999) J. Immunol. 163, 4647-4650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmieg, J., Yang, G., Franck, R. W. & Tsuji, M. (2003) J. Exp. Med. 198, 1631-1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hayakawa, Y., Takeda, K., Yagita, H., Kakuta, S., Iwakura, Y., Van Kaer, L., Saiki, I. & Okumura, K. (2001) Eur. J. Immunol. 31, 1720-1727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eberl, G. & MacDonald, H. R. (2000) Eur. J. Immunol. 30, 985-992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kitamura, H., Ohta, A., Sekimoto, M., Sato, M., Iwakabe, K., Nakui, M., Yahata, T., Meng, H., Koda, T., Nishimura, S., et al. (2000) Cell. Immunol. 199, 37-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stanic, A. K., Shashidharamurthy, R., Bezbradica, J. S., Matsuki, N., Yoshimura, Y., Miyake, S., Choi, E. Y., Schell, T. D., Van Kaer, L., Tevethia, S. S., et al. (2003) J. Immunol. 171, 4539-4551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benlagha, K., Kyin, T., Beavis, A., Teyton, L. & Bendelac, A. (2002) Science 296, 553-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gumperz, J. E., Miyake, S., Yamamura, T. & Brenner, M. B. (2002) J. Exp. Med. 195, 625-636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee, P. T., Benlagha, K., Teyton, L. & Bendelac, A. (2002) J. Exp. Med. 195, 637-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gadue, P. & Stein, P. L. (2002) J. Immunol. 169, 2397-2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pellicci, D. G., Hammond, K. J., Uldrich, A. P., Baxter, A. G., Smyth, M. J. & Godfrey, D. I. (2002) J. Exp. Med. 195, 835-844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sidobre, S., Naidenko, O. V., Sim, B. C., Gascoigne, N. R., Garcia, K. C. & Kronenberg, M. (2002) J. Immunol. 169, 1340-1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kang, S. J. & Cresswell, P. (2004) Nat. Immunol. 5, 175-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moody, D. B. & Porcelli, S. A. (2003) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3, 11-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winau, F., Schwierzeck, V., Hurwitz, R., Remmel, N., Sieling, P. A., Modlin, R. L., Porcelli, S. A., Brinkmann, V., Sugita, M., Sandhoff, K., et al. (2004) Nat. Immunol. 5, 169-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou, D., Cantu, C., III, Sagiv, Y., Schrantz, N., Kulkarni, A. B., Qi, X., Mahuran, D. J., Morales, C. R., Grabowski, G. A., Benlagha, K., et al. (2004) Science 303, 523-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goff, R. D., Gao, Y., Mattner, J., Zhou, D., Yin, N., Cantu, C., III, Teyton, L., Bendelac, A. & Savage, P. B. (2004) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 13602-13603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oki, S., Chiba, A., Yamamura, T. & Miyake, S. (2004) J. Clin. Invest. 113, 1631-1640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bonish, B., Jullien, D., Dutronc, Y., Huang, B. B., Modlin, R., Spada, F. M., Porcelli, S. A. & Nickoloff, B. J. (2000) J. Immunol. 165, 4076-4085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Colgan, S. P., Pitman, R. S., Nagaishi, T., Mizoguchi, A., Mizoguchi, E., Mayer, L. F., Shao, L., Sartor, R. B., Subjeck, J. R. & Blumberg, R. S. (2003) J. Clin. Invest. 112, 745-754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brossay, L., Jullien, D., Cardell, S., Sydora, B. C., Burdin, N., Modlin, R. L. & Kronenberg, M. (1997) J. Immunol. 159, 1216-1224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park, S. H., Roark, J. H. & Bendelac, A. (1998) J. Immunol. 160, 3128-3134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roark, J. H., Park, S. H., Jayawardena, J., Kavita, U., Shannon, M. & Bendelac, A. (1998) J. Immunol. 160, 3121-3127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lang, G. A., Maltsev, S. D., Besra, G. S. & Lang, M. L. (2004) Immunology 112, 386-396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Buatois, V., Baillet, M., Becart, S., Mooney, N., Leserman, L. & Machy, P. (2003) J. Immunol. 171, 5812-5819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.