Abstract

Objective

To compare the costs associated with adjunctive azithromycin compared to standard cefazolin antibiotic prophylaxis alone for unscheduled and scheduled cesarean deliveries.

Methods

A decision analytic model was created to compare cefazolin alone to azithromycin plus cefazolin. Published incidences of surgical site infection after cesarean delivery were used to estimate the baseline incidence of surgical site infection in scheduled and unscheduled cesarean using standard antibiotic prophylaxis. The effectiveness of adjunctive azithromycin prophylaxis was obtained from published randomized control trials for unscheduled cesarean sections. No randomized study of its use in scheduled procedures has been completed. Cost estimates were obtained from published literature, hospital estimates, and the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project and considered costs of azithromycin and surgical site infections. A series of sensitivity analyses were conducted by varying parameters in the model based on observed distributions for probabilities and costs. The outcome was cost per cesarean delivery from a health system perspective.

Results

For unscheduled cesarean deliveries, cefazolin prophylaxis alone would cost $695 compared to $335 for adjunctive azithromycin prophylaxis, resulting in a savings of $360 (95% CI $155–$451) per cesarean. In scheduled cesarean deliveries, cefazolin prophylaxis alone would cost $254, compared to $111 for adjunctive azithromycin prophylaxis, resulting in a savings of $143 (95% CI 98–157) per cesarean, if proven effective. These findings were robust to a multitude of inputs; as long as adjunctive azithromycin prevented as few as seven additional surgical site infections per 1,000 unscheduled cesarean deliveries and nine additional surgical site infections per 10,000 scheduled cesarean deliveries, adjunctive azithromycin prophylaxis was cost-saving.

Conclusion

Adjunctive azithromycin prophylaxis is a cost-saving strategy in both unscheduled and scheduled cesarean deliveries.

Introduction

Cesarean delivery is the most common major surgical procedure performed in the United States, with over 1.2 million performed annually.(1) Up to 12% of the cesarean deliveries performed in the US each year are complicated by surgical site infection,(2) a significant cause of preventable morbidity and mortality.(3)

A recent study by Tita et al(4) demonstrated that the addition of a single dose of perioperative azithromycin in addition to the standard first generation cephalosporin in women undergoing unscheduled cesarean reduces the risk of infectious morbidities (including endometritis and wound infections) by 50%. While this study provides strong evidence supporting the effectiveness of the azithromycin-based extended-spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis regimen in women undergoing unscheduled cesarean, a crucial question highlighted by an accompanying editorial(5) remains whether the extended-spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis is cost-effective.

The trial by Tita et al did not included scheduled cesarean deliveries, and while observational studies including scheduled cesarean deliveries are supportive, the potential benefit of azithromycin prophylaxis for scheduled cesarean deliveries remains uncertain.(4, 6, 7) We thought it was important to included scheduled cesarean deliveries in this economic analysis despite the lack of clinical trial data for several reasons. First, scheduled cesarean deliveries account for at least 40% of cesarean deliveries annually.(8, 9) Second, although the incidence of post-cesarean infection is much lower in scheduled than unscheduled cesareans, the incidence is 4% or higher, accounting for over 25,000 surgical site infections per year in the US and many more globally. Third, historically there was a long delay in considering standard cephalosporin antibiotic prophylaxis for scheduled cesareans, whereas we now know if is equally efficacious in scheduled and unscheduled cesareans.

Therefore, we aimed to use decision analytic methods to estimate the impact on costs for perioperative adjunctive azithromycin (in addition to standard prophylactic antibiotics) compared to the standard cefazolin alone in preventing surgical site infection. Because the risk of surgical site infection is lower in scheduled compared to unscheduled cesareans,(10) we performed this analysis separately for both unscheduled and scheduled cesareans. This information will be useful to healthcare leaders and obstetric care providers considering whether to use adjunctive azithromycin in unscheduled and whether to extend the use to scheduled cesareans.

Materials and Methods

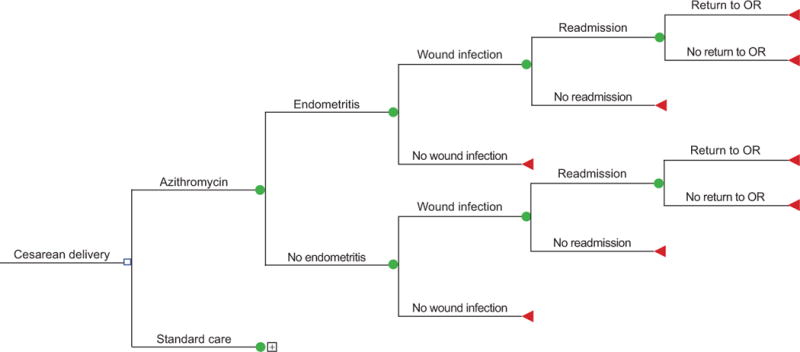

We constructed a decision analytic model (Figure 1) to compare the costs of adding a single perioperative dose of azithromycin to standard cesarean care for the prevention of post-operative surgical site infections (endometritis and/or wound infection). The model was constructed using TreeAge Pro 2015 (TreeAge Software, Inc., Williamstown, MA). All data used in the analysis came from the published literature and thus this study was exempt from institutional board review.

Figure 1.

Decision tree comparing costs with adjunctive azithromycin compared to standard antibiotics for cesarean delivery. OR, operating room.

Model inputs included the probability of endometritis and surgical site infections in women undergoing scheduled as well as unscheduled cesarean deliveries,(11) the effectiveness (effect size) of azithromycin in preventing adverse outcomes,(4) the cost and likelihood of readmission(4, 12–14) and of return to the operating room if an infection occurred,(12) the risk of anaphylaxis (15), the cost of azithromycin,(16–20) and the costs of treating adverse outcomes (including anaphylaxis) in outpatient(21) or inpatient settings.(22–25) The costs of outpatient management of wound infection including the cost of home health and physicians visits. Because the costs of cesarean delivery and cefazolin are equivalent in both arms of the model and would precisely cancel out, these costs were not included in the model. Cost estimates were obtained from hospital estimates (cost of azithromycin), and the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (for inpatient hospital costs), and published literature (all other costs). The decision model was then used to calculate expected values for the costs of prophylaxis and for treating infections incurred under standard care. This model assumes that azithromycin would be used as an adjunct to standard care antibiotic prophylaxis rather than as a substitute. All costs were converted to constant 2016 dollars using the medical component of the consumer price index.(26)

Once the baseline primary results for unscheduled cesareans were obtained, a series of sensitivity analyses were conducted by varying parameters in the model based on observed distributions for probabilities and costs. For probabilities, 95% confidence intervals were estimated using Monte Carlo simulations drawn from beta distributions estimated from the published data. Where parametric cost distributions were reported in the literature, the ranges used in sensitivity analyses were the mean ± two standard deviations. Where no information on distributions was available, we simply varied the costs across the full range of costs available from any source. Two-way sensitivity analyses were used assessing the effect on expected values when both infection incidence and the effectiveness of treatment were varied together. In additional analyses a similar procedure was used to assess the cost-effectiveness of scheduled cesareans. Analyses were performed from a health system perspective, where cost savings are based on health system (not patient) expenses.

Results

Table 1 shows the baseline model inputs derived from published manuscripts, along with the ranges used for the sensitivity analyses and the data sources for each of the parameters.

Table 1.

Baseline Values and Ranges for Model Inputs

| Probability | Baseline | 95% CI | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scheduled Cesarean – Risks of Complication with Standard Antibiotic Prophylaxis | |||

| Wound Infection | 0.041 | 0.031–0.051 | Tuuli et al(13) |

| Endometritis | 0.018 | 0.011–0.026 | Smaill et al(11) |

| Unscheduled Cesarean-Risks of Complications with Standard Antibiotic Prophylaxis | |||

| Wound Infection | 0.075 | 0.053–0.101 | Tuuli et al(13) |

| Endometritis | 0.103 | 0.087–0.120 | Smaill et al(11) |

| Rehospitalization for SSI | 0.327 | 0.285–0.369 | Tuuli et al(13) Tita et al(4) Kamat et al(12) Mackeen et al(36) Perencevich et al(14) |

| Return to OR if Hospitalized | 0.357 | 0.101–0.613 | Kamat et al(12) |

| Anaphylaxis to Azithromycin | 0.009 | 0.000–0.015 | FDA Documents(29) |

| Azithromycin Effect (Relative Risk) | |||

| Wound Infection | 0.35 | 0.22–0.56 | Tita et al(4) |

| Endometritis | 0.62 | 0.42–0.92 | Tita et al(4) |

| Costs (2016 USD) | |||

| Azithromycin | $5.14 | $2.74–59.98 | Paladino et al(16) Samsa et al(17) University Pharmacies Price Lists(18–20) |

| Endometritis | $5,012 | $4,411–5,697 | Olsen et al(22) |

| Wound Infection (Outpatient) | $3,123 | $1,833–5,017 | Echebiri et al(21) |

| Readmission, no OR | $6,997 | $6,763–7,232 | Healthcare Utilization Project, 2013 Data(24) |

| Readmission with return to OR | $10,344 | $9,554–11,134 | Healthcare Utilization Project, 2013 Data(24) |

| Anaphylaxis | $784 | $392–1,176 | Chelmow et al(25) |

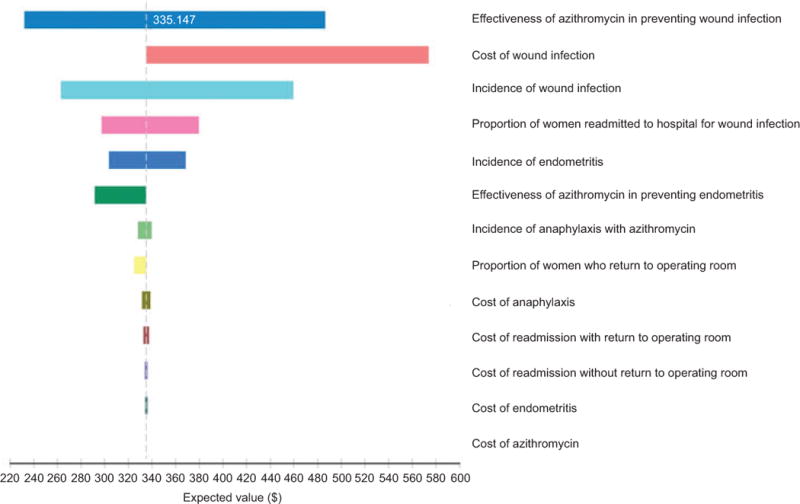

In the base case analysis for unscheduled cesareans, adding azithromycin to standard care in low risk women resulted in a savings of $360 (95% CI $155–$451) per unscheduled cesarean, reducing expected costs from $695 for standard of care to $335 with adjunctive azithromycin. A series of one-way sensitivity analyses, illustrated in Figure 2, found that azithromycin was cost-saving in all sensitivity analyses. The most influential parameter was the effectiveness of adjunctive azithromycin to prevent adverse outcomes, the next most influential parameter was the incidence rate for SSIs. In our baseline model, even varying the effectiveness to the least favorable values of azithromycin effectiveness, 0.92 and 0.56, for endometritis and wound infections, respectively, still produced lower expected costs with the addition of azithromycin.

Figure 2.

Tornado diagram of one-way sensitivity analyses for costs associated with adjunctive azithromycin prophylaxis in unscheduled cesarean delivery. Expected value: $335.

The only two-way sensitivity analyses to make any difference in our findings consisted of varying the effectiveness of azithromycin to prevent wound infection and the probability of wound infection, while holding the effectiveness of azithromycin on endometritis to a RR of 0.98, which exceeds the worst-case scenario for azithromycin preventing endometritis (RR 0.92). For standard care to be less costly than the addition of azithromycin, the probability of wound infection would need to be less than 2 in 10,000 or the risk reduction for azithromycin would need to be greater than 0.9991. This is equivalent to stating azithromycin would be cost saving as long as it prevented more than 9 additional wound infections per 10,000 deliveries compared to standard cefazolin prophylaxis.

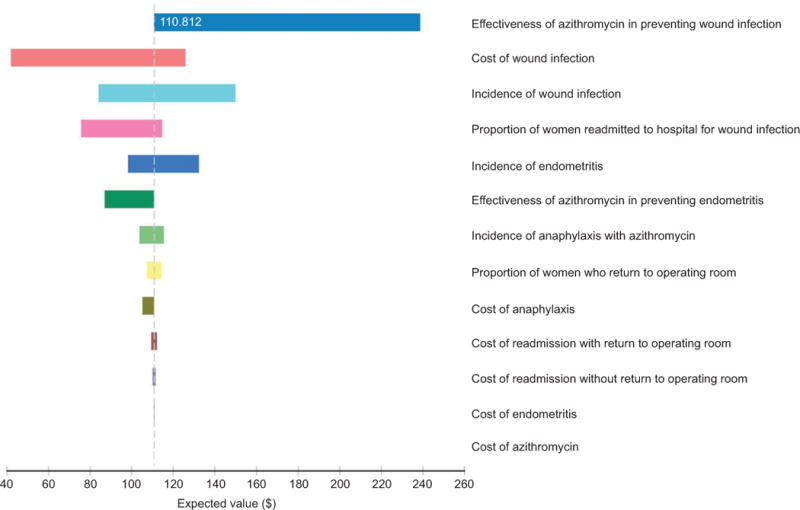

In the base case analysis of scheduled cesarean deliveries, adding azithromycin to standard care in the low risk women resulted in a savings of $143 (95% CI $98–$157) per scheduled cesarean delivery, reducing expected costs from $254 for standard care to $111 with the addition of azithromycin. A series of one-way sensitivity analyses found that no parameter variance would alter the finding that adding azithromycin to standard prophylaxis would result in cost savings. These sensitivity analyses are illustrated in a tornado diagram in Figure 3; on the x-axis of this diagram is the expected value and the y-axis is each parameter considered in the model. As each parameter is varied over its entire 95% confidence interval, the expected value remains above $0 (cost-saving). The most influential parameter was the effectiveness of azithromycin (relative risk range 0.22–0.56) to prevent adverse outcomes, and the next most influential parameter was the incidence of wound infections (range 3.1–5.1%). In the study by Tita and colleagues,(4) the addition of azithromycin to standard antibiotic prophylaxis for unscheduled cesarean deliveries resulted in a relative risk of 0.62 (95% CI 0.42–0.92) for endometritis and 0.35 (95% 0.22–0.56) for wound infection. In our baseline model, even varying the effectiveness to the least favorable values for the effectiveness of azithromycin (relative risk of 0.92 for endometritis and relative risk of 0.56 for wound infections) still produced lower overall expected costs with the addition of azithromycin compared to no cefazolin alone.

Figure 3.

Tornado diagram of one-way sensitivity analyses for costs associated with adjunctive azithromycin prophylaxis in scheduled cesarean delivery. Expected value: $111.

The only two-way sensitivity analyses to make any difference in our findings consisted of varying the effectiveness of azithromycin to prevent surgical site infection and the probability of surgical site infection, while holding the effectiveness of azithromycin on prevention of endometritis to a relative risk of 0.92 (the least favorable scenario). For standard care to be less costly than adjunctive azithromycin, the probability of surgical site infection (endometritis or wound infection) would need to be less than 8.2 per 10,000 scheduled cesarean deliveries (compared to the estimated incidence of 3–5% for wound infections and 1.8% for endometritis) or the relative risk of wound infection with azithromycin would need to be greater than 0.993. In other words, azithromycin would be cost saving as long as it prevented more than seven surgical site infections in 1,000 scheduled cesarean deliveries.

Discussion

We found that the addition of routine azithromycin to standard antibiotic prophylaxis for unscheduled cesarean delivery, azithromycin resulted in a cost savings of $360 per scheduled cesarean performed. Among scheduled cesareans, the cost-savings were $143 per cesarean performed, assuming that azithromycin is demonstrated effective. These savings will likely vary by region based on costs at each hospital. If broadly implemented across the United States where over 1.2 million cesarean deliveries are performed annually, a single dose of perioperative azithromycin could result in over $300 million worth of cost-savings annually.

Our models for scheduled and unscheduled cesareans were remarkably robust to a multitude of inputs. Varying each individual parameter in the model over its entire range did not result in any situation where the addition of azithromycin to standard perioperative antibiotics was not cost-effective. In two-way sensitivity analyses, the only situations in which azithromycin prophylaxis was not cost-effective was at extremely low incidences of wound infection (<0.02% for unscheduled and <0.0018% for scheduled cesarean) and extremely low effectiveness of azithromycin at preventing endometritis. At these low baseline risks of infection, azithromycin would still be cost effective (and in fact cost-saving) if it prevented at least seven surgical site infections in 1,000 scheduled cesarean deliveries (RR of 0.997) and at least nine surgical site infections in 10,000 unscheduled cesarean deliveries (RR of 0.9991). Based on prior studies, the frequency of post-cesarean wound infection with routine use of standard antibiotics in low risk scheduled cesarean delivery is uniformly above 2 to 4% and the effect size of azithromycin-based antibiotic prophylaxis is expected to be above 0.997.

The main limitation of this model is the lack of strong clinical trial data demonstrating that adjunctive azithromycin is effective at preventing post-cesarean surgical site infections specifically in women who undergo scheduled cesarean delivery. However, we believe this to be a reasonable assumption for several reasons. First, azithromycin likely prevents surgical site infection by extending the antimicrobial coverage to additional species including Ureaplasma species, which have been found in the chorioamnion of women who have not labored and have intact membranes.(27) Additionally, an earlier single institutional experience with azithromycin-based extended spectrum antibiotics compared to cephalosporin alone included a significant proportion of women with scheduled cesarean deliveries.(6, 28) This experience suggested that extended spectrum antibiotics decreased the risk of endometritis and wound infection in both scheduled and unscheduled cesareans. Finally, by analogy, a metaanalysis assessing the benefits of standard antibiotic prophylaxis for cesarean delivery assessed for heterogeneity of the intervention by whether or not the cesarean was scheduled or unscheduled. The risk reduction for endometritis with standard antibiotic prophylaxis was similar in scheduled and unscheduled cesarean deliveries (RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.24–0.61, and RR 0.39, 95% 0.33–0.47, respectively); the risk reduction for wound infection was slightly less in scheduled compared to unscheduled deliveries (RR 0.62, 95% 0.47–0.82, versus 0.34, 95% CI 0.28–0.40). While the test for interaction was significant for wound infection, no interaction was found for all febrile morbidity, endometritis, or serious infectious morbidity and all included studies suggested that standard antibiotics reduced the risk of infection in scheduled and unscheduled cesareans.(11)

We estimate that a randomized trial or systematic review of randomized trials to evaluate adjunctive azithromycin prophylaxis for scheduled cesarean would require a sample size of approximately 1,500–3,100 women based on a baseline infection risk of 4–6%, effect size of 33–40% and power of 80%. However, as our model was cost effective at a relative risk of 0.997 for scheduled cesarean, a sample size of over 100,000 women would be necessary to detect a much smaller effect size of 10%. A trial of this size is unlikely to be performed due to both feasibility and cost.

Adjunctive azithromycin use for cesarean prophylaxis has some downsides. The reported incidence of anaphylaxis to azithromycin is <1%, and side effects and antibiotic resistance should be minimal with a single perioperative dose.(29) Common principles of choosing an antimicrobial agent for surgical prophylaxis include that the agent should prevent surgical site infection, produce no adverse effects, be active against the pathogens likely to contaminate the surgical site, and reduce the duration and cost of healthcare.(30) Adjunctive azithromycin prophylaxis for cesarean meets these common principles and is likely to be effective in women undergoing scheduled cesarean. Concerns regarding effects on infant microbiome and long-term childhood outcomes particularly involving the gastrointestinal system and neurodevelopment have been raised and are of uncertain significance although certainly deserving of long-term follow-up.(31–34) Similar concerns were raised regarding the use of cefazolin; a meta-analysis of studies comparing cefazolin before or after cord clamping have found no difference in neonatal outcomes.(35)

Therefore, on balance, pending large studies to address these issues and confirm efficacy in scheduled cesareans, our findings support the use of adjunctive azithromycin antibiotic prophylaxis for women undergoing unscheduled cesarean delivery as cost-saving. Adjunctive azithromycin prophylaxis is also likely to be cost-saving in those undergoing scheduled cesarean delivery and deserves additional investigation.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure

The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Each author has indicated that he or she has met the journal’s requirements for authorship.

References

- 1.Hamilton BEMJ, Osterman MJK, et al. Births: Final data for 2014. National vital statistics reports. 2015;64(12) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conroy K, Koenig AF, Yu YH, Courtney A, Lee HJ, Norwitz ER. Infectious morbidity after cesarean delivery: 10 strategies to reduce risk. Reviews in obstetrics & gynecology. 2012;5(2):69–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berg CJ, Chang J, Callaghan WM, Whitehead SJ. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 1991–1997. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2003 Feb;101(2):289–96. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02587-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tita ATN, Szychowski JM, Boggess K, Saade G, Longo S, Clark E, et al. Adjunctive Azithromycin Prophylaxis for Cesarean Delivery. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;375(13):1231–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinstein RA, Boyer KM. Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Cesarean Delivery – When Broader Is Better. The New England journal of medicine. 2016 Sep 29;375(13):1284–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1610010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tita AT, Owen J, Stamm AM, Grimes A, Hauth JC, Andrews WW. Impact of extended-spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis on incidence of postcesarean surgical wound infection. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2008 Sep;199(3):303.e1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tita AT, Hauth JC, Grimes A, Owen J, Stamm AM, Andrews WW. Decreasing incidence of postcesarean endometritis with extended-spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2008 Jan;111(1):51–6. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000295868.43851.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang J, Troendle J, Reddy UM, Laughon SK, Branch DW, Burkman R, et al. Contemporary cesarean delivery practice in the United States. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2010 Oct;203(4):326 e1–e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.06.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Timofeev J, Reddy UM, Huang CC, Driggers RW, Landy HJ, Laughon SK. Obstetric complications, neonatal morbidity, and indications for cesarean delivery by maternal age. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2013 Dec;122(6):1184–95. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hemsell DL. Prophylactic antibiotics in gynecologic and obstetric surgery. Rev Infect Dis. 1991 Sep-Oct;13(Suppl 10):S821–41. doi: 10.1093/clinids/13.supplement_10.s821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smaill FM, Grivell RM. Antibiotic prophylaxis versus no prophylaxis for preventing infection after cesarean section. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2014;10:Cd007482. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007482.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamat AA, Brancazio L, Gibson M. Wound infection in gynecologic surgery. Infectious diseases in obstetrics and gynecology. 2000;8(5–6):230–4. doi: 10.1155/S1064744900000338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tuuli MG, Liu J, Stout MJ, Martin S, Cahill AG, Odibo AO, et al. A Randomized Trial Comparing Skin Antiseptic Agents at Cesarean Delivery. The New England journal of medicine. 2016 Feb 18;374(7):647–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perencevich EN, Sands KE, Cosgrove SE, Guadagnoli E, Meara E, Platt R. Health and economic impact of surgical site infections diagnosed after hospital discharge. Emerging infectious diseases. 2003 Feb;9(2):196–203. doi: 10.3201/eid0902.020232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2001/50733s5lbl.pdf. [cited 6/6/16]; Available from:

- 16.Paladino JA, Gudgel LD, Forrest A, Niederman MS. Cost-effectiveness of IV-to-oral switch therapy: azithromycin vs cefuroxime with or without erythromycin for the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2002 Oct;122(4):1271–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.4.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Samsa GP, Matchar DB, Harnett J, Wilson J. A cost-minimization analysis comparing azithromycin-based and levofloxacin-based protocols for the treatment of patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia: results from the CAP-IN trial. Chest. 2005 Nov;128(5):3246–54. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.5.3246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.https://masshealthdruglist.ehs.state.ma.us/MHDL/pubtheradetail.do?id=213. [cited 6/6/2016]; Available from:

- 19.http://www.cumc.columbia.edu/dept/id/documents/IVToPOPolicyUpdate5-4-11.pdf. [cited 6/6/16]; Columbia University Medical Center Pharmacy Costs]. Available from:

- 20.http://www.uwhealth.org/files/uwhealth/docs/antimicrobial/Antimicrobial_Use_Guidelines_including_all_appendices.pdf. [cited 6/6/16]; University of Wisconsin Hospital & Clincis Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee Department of Pharmacy Drug Policy Program]. Available from:

- 21.Echebiri NC, McDoom MM, Aalto MM, Fauntleroy J, Nagappan N, Barnabei VM. Prophylactic use of negative pressure wound therapy after cesarean delivery. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2015 Feb;125(2):299–307. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olsen MA, Butler AM, Willers DM, Gross GA, Fraser VJ. Comparison of costs of surgical site infection and endometritis after cesarean delivery using claims and medical record data. Infection control and hospital epidemiology. 2010 Aug;31(8):872–5. doi: 10.1086/655435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olsen MA, Butler AM, Willers DM, Gross GA, Hamilton BH, Fraser VJ. Attributable costs of surgical site infection and endometritis after low transverse cesarean delivery. Infection control and hospital epidemiology : the official journal of the Society of Hospital Epidemiologists of America. 2010 Mar;31(3):276–82. doi: 10.1086/650755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Westerman S, Wenger NK. Women and heart disease, the underrecognized burden: sex differences, biases, and unmet clinical and research challenges. Clinical science (London, England: 1979) 2016 Apr;130(8):551–63. doi: 10.1042/CS20150586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chelmow D, Hennesy M, Evantash EG. Prophylactic antibiotics for non-laboring patients with intact membranes undergoing cesarean delivery: an economic analysis. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2004 Nov;191(5):1661–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.03.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hemal K, Pagidipati NJ, Coles A, Dolor RJ, Mark DB, Pellikka PA, et al. Sex Differences in Demographics, Risk Factors, Presentation, and Noninvasive Testing in Stable Outpatients With Suspected Coronary Artery Disease: Insights From the PROMISE Trial. JACC Cardiovascular imaging. 2016 Apr;9(4):337–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andrews WW, Shah SR, Goldenberg RL, Cliver SP, Hauth JC, Cassell GH. Association of post-cesarean delivery endometritis with colonization of the chorioamnion by Ureaplasma urealyticum. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1995 Apr;85(4):509–14. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(94)00436-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andrews WW, Hauth JC, Cliver SP, Savage K, Goldenberg RL. Randomized clinical trial of extended spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis with coverage for Ureaplasma urealyticum to reduce post-cesarean delivery endometritis. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2003 Jun;101(6):1183–9. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang MH, Moonesinghe R, Athar HM, Truman BI. Trends in Disparity by Sex and Race/Ethnicity for the Leading Causes of Death in the United States-1999–2010. Journal of public health management and practice: JPHMP. 2016 Jan-Feb;22(Suppl 1):S13–24. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bratzler DW, Dellinger EP, Olsen KM, Perl TM, Auwaerter PG, Bolon MK, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery. Surgical infections. 2013 Feb;14(1):73–156. doi: 10.1089/sur.2013.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sudo N, Sawamura S, Tanaka K, Aiba Y, Kubo C, Koga Y. The requirement of intestinal bacterial flora for the development of an IgE production system fully susceptible to oral tolerance induction. J Immunol. 1997 Aug 15;159(4):1739–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ragusa A, Svelato A. Adjunctive Azithromycin Prophylaxis for Cesarean Delivery. The New England journal of medicine. 2017 Jan 12;376(2):181–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1614626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rautava S. Early microbial contact, the breast milk microbiome and child health. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2016 Feb;7(1):5–14. doi: 10.1017/S2040174415001233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walker WA. Initial intestinal colonization in the human infant and immune homeostasis. Ann Nutr Metab. 2013;63(Suppl 2):8–15. doi: 10.1159/000354907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mackeen AD, Packard RE, Ota E, Berghella V, Baxter JK. Timing of intravenous prophylactic antibiotics for preventing postpartum infectious morbidity in women undergoing cesarean delivery. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2014 Dec;05(12):Cd009516. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009516.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mackeen AD, Khalifeh A, Fleisher J, Vogell A, Han C, Sendecki J, et al. Suture compared with staple skin closure after cesarean delivery: a randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2014 Jun;123(6):1169–75. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]