Abstract

Autonomic dysreflexia (AD) and neuropathic pain occur after severe injury to higher levels of the spinal cord. Mechanisms underlying these problems have rarely been integrated in proposed models of spinal cord injury (SCI). Several parallels suggest significant overlap of these mechanisms, although the relationships between sympathetic function (dysregulated in AD) and nociceptive function (dysregulated in neuropathic pain) are complex. One general mechanism likely to be shared is central sensitization – enhanced responsiveness and synaptic reorganization of spinal circuits that mediate sympathetic reflexes or that process and relay pain-related information to the brain. Another is enhanced sensory input to spinal circuits caused by extensive alterations in primary sensory neurons. Both AD and SCI-induced neuropathic pain are associated with spinal sprouting of peptidergic nociceptors that might increase synaptic input to the circuits involved in AD and SCI pain. In addition, numerous nociceptors become hyperexcitable, hypersensitive to chemicals associated with injury and inflammation, and spontaneously active, greatly amplifying sensory input to sensitized spinal circuits. As discussed with the aid of a preliminary functional model, these effects are likely to have mutually reinforcing relationships with each other, and with consequences of SCI-induced interruption of descending excitatory and inhibitory influences on spinal circuits, with SCI-induced inflammation in the spinal cord and in DRGs, and with activity in sympathetic fibers within DRGs that promotes local inflammation and spontaneous activity in sensory neurons. This model suggests that interventions selectively targeting hyperactivity in C-nociceptors might be useful for treating chronic pain and AD after high SCI.

Keywords: Sympathetic nervous system, Neuropathic pain, Neuroinflammation, Nociceptor, Dorsal root ganglion, Central sensitization

1. Introduction

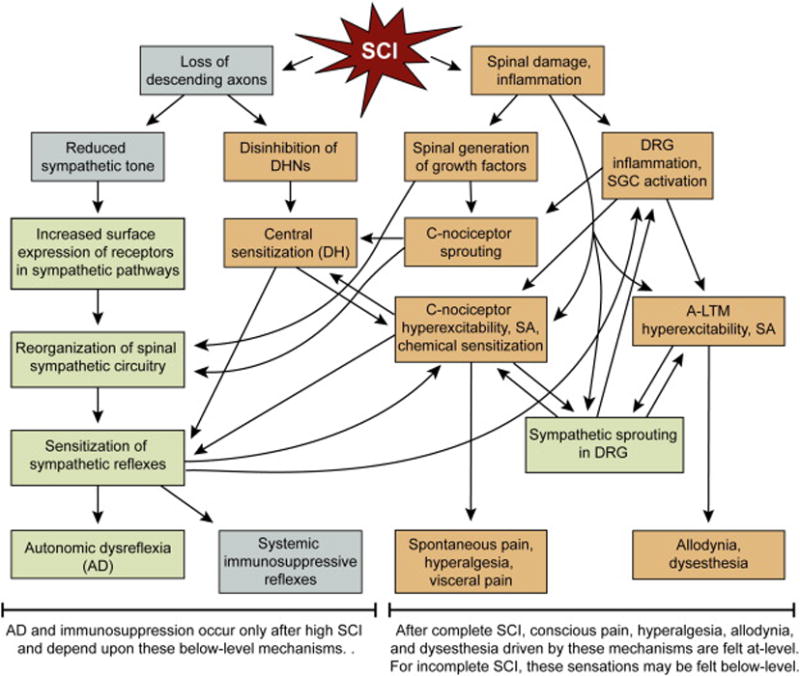

Two chronic consequences of spinal cord injury (SCI) that cause considerable distress are autonomic dysreflexia (AD) and neuropathic pain. These largely intractable conditions frequently coexist and involve mechanisms that are not well understood but are often assumed to overlap partially. While examination of the relationships between SCI-induced AD and pain would be expected to shed light on mechanisms they share, there has been relatively little explicit consideration of how they are interrelated. This review focuses on potentially important mechanistic interrelationships implicated in recent physiological studies. Some of these interrelationships are complex, so for clarity and to encourage further research, a preliminary functional model (Fig. 1) of mechanisms that contribute to both AD and neuropathic SCI pain is referred to throughout this review.

Fig. 1.

A preliminary functional model for interactions among sympathetic activity, innate immune function (inflammation), and hyperfunctional DRG neurons that promote chronic SCI-induced AD and neuropathic pain. This model primarily addresses mechanisms common to both AD and chronic neuropathic pain following high, severe SCI (clinically complete or largely complete). For supporting evidence and citations see text throughout this article. For a concise explanation of the model, see Section 6. Gray boxes – reduced function. Green boxes – increased function in sympathetic pathways. Tan boxes – increased function in pain pathways. AD – autonomic dysreflexia, A-LTM – A fiber low threshold mechanoreceptor, DH – spinal dorsal horn, DHN – dorsal horn neuron, DRG – dorsal root ganglion, SGC – satellite glial cell, SCI – spinal cord injury, SA – spontaneous (ongoing) activity. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

2. Autonomic dysreflexia (AD) and SCI

2.1. Anatomical aspects of autonomic dysregulation after SCI

Because SCI interrupts descending neural pathways in the spinal cord (Fig. 1), and the activity of autonomic preganglionic neurons in the spinal cord is regulated by inputs from various parts of the brain (Deuchars and Lall, 2015; Loewy, 1981), SCI would be expected to cause significant problems for both sympathethic and parasympathetic functions. Indeed, autonomic consequences of SCI include dysregulation of cardiovascular, thermoregulatory, respiratory, digestive, urinary, and sexual function (Hou and Rabchevsky, 2014). The anatomy of the autonomic nervous system means that the nature and degree of functional dysregulation produced by SCI depend upon the level of the injury. While all sympathetic preganglionic neurons have their cell bodies and dendrites within the spinal cord (in thoracic segments T1 to T12 and upper lumbar segments L1 and L2/L3), only the sacral division of the parasympathetic system has preganglionic neurons in the spinal cord (in segments L3 to L5 and S1 to S5). A large number of parasympathetic preganglionic neurons are located in cranial nuclei within the brainstem. All sympathetic and parasympathetic preganglionic neurons with cell bodies in spinal segments send their axons out of the spinal cord via ventral roots. Cranial parasympathetic preganglionic neurons send their axons to parasympathetic ganglia of the head via corresponding cranial nerves or to postganglionic neurons in the chest and abdomen via the vagus nerve (cranial nerve X). Thus, complete SCI at almost any level will eliminate descending control of parasympathetic functions mediated by sacral preganglionic neurons (causing urinary, sexual, and some gastrointestinal problems) but will have no direct effect on parasympathetic functions mediated by cranial nerves, including the vagus nerve, which innervates upper abdominal and thoracic organs, including the heart. Importantly, complete SCI at any cervical level will eliminate descending control of all sympathetic preganglionic neurons, and complete SCI at thoracic levels will eliminate descending control of lower thoracic and lumbar preganglionic neurons (Llewellyn-Smith et al., 2006). SCI at cervical or higher thoracic segments causes resting hypotension, presumably because of loss of tonic descending background excitation of sympathetic preganglionic neurons that excite postganglionic neurons innervating vascular resistance vessels—although reorganization of below-level autonomic circuitry after SCI (Ueno et al., 2016) complicates this assumption. A related disturbance is orthostatic hypotension—large drops in blood pressure when changing to an upright position. While chronic hypotension can have adverse effects (including dizziness, syncope, lethargy, mood disturbance, and impaired cognitive function (Phillips and Krassioukov, 2015), the most dangerous autonomic consequence of severe high SCI (at or above segment T5) is autonomic dysreflexia (AD), which will be the autonomic focus of this article.

2.2. Properties, significance, and mechanisms of AD induced by SCI

AD is defined as episodes of sympathetically driven reflexive hypertension accompanied by secondary, baroreceptor-induced, vagally mediated bradycardia. It is often associated with severe headache, acute anxiety, flushing, sweating, and shivering (Rabchevsky, 2006). AD appears to result from intense sympathetic stimulation of vasoconstriction, opposed in the periphery solely by reflexive vagal slowing of heart rate (because the upper parasympathetic system, although intact, innervates relatively few resistance vessels and thus cannot contribute significantly to homeostatic control of blood pressure by reducing total peripheral resistance). AD is dangerous because of the magnitude of blood pressure elevation, which can be directly life threatening, and because it can exacerbate other manifestations of SCI-induced cardiovascular disease, which, taken together, is now recognized as the leading cause of death in chronic SCI patients (Phillips and Krassioukov, 2015). Chronic AD occurs in at least a quarter of SCI patients with injuries at or above T5, and tends to be more common after more complete injuries (Furusawa et al., 2011; Helkowski et al., 2003; Lindan et al., 1980). While the properties of AD are well understood at the physiological level, the mechanisms responsible for triggering AD and for the severity of each episode have yet to be defined conclusively. An intriguing clue comes from the observation that AD is commonly triggered by sensory input that would either be painful under normal conditions or could be painful under conditions of heightened pain sensitivity (Krenz and Weaver, 1998; Rabchevsky, 2006; Hou and Rabchevsky, 2014). Interestingly, high SCI not only is required for AD, but is associated with the highest prevalence of chronic neuropathic pain (Kramer et al., 2016). Implications of these observations will be discussed below.

3. Neuropathic pain and SCI

3.1. SCI-induced nociceptive pain

Chronic pain occurs in about three quarters of SCI patients (Andresen et al., 2016) and comprises two major classes. The first class is nociceptive pain, which corresponds to pain experiences that are all too familiar to most people. Nociceptive pain results from activity generated by normal mechanisms in the peripheral terminals of primary sensory neurons called nociceptors. These neurons have cell bodies in dorsal root ganglia (DRG) or trigeminal ganglia and either superficial or deep receptive fields in the body that detect local signs of actual or incipient tissue injury, including inflammatory signals. Nociceptive pain is secondary to many sequelae of SCI that affect the musculoskeletal system, including overuse of the upper body, muscle weakness, poor posture, and spasticity (Finnerup and Baastrup, 2012). Nociceptive pain after SCI also includes pain generated in the skin by pressure sores or in the viscera by constipation, as well as headache caused by AD. While nociceptive pain has traditionally been distinguished from neuropathic pain by a dependence upon activation of primary sensory neurons for nociceptive pain and an absence of such dependence for neuropathic pain, recent studies to be reviewed below reveal that aberrant sensory neuron activation can also contribute substantially to neuropathic pain.

3.2. Properties of SCI-induced neuropathic pain

The second class of SCI pain, neuropathic pain, is defined as pain caused by damage or disease of the nervous system (Jensen et al., 2011). Unlike nociceptive pain, neuropathic pain caused by SCI is considered a purely pathological, maladaptive consequence of central nervous system damage and inflammation rather than a potentially useful protective response (Gwak and Hulsebosch, 2011; Walters, 2012). Neuropathic pain occurs in half or more of all SCI patients and is usually permanent and resistant to treatment (Finnerup and Baastrup, 2012). Neuropathic SCI pain is further divided into at-level and below-level pain (Fig. 1), which are felt, respectively, “at” the spinal injury level (defined as bodily pain felt at the injury level and up to 3 segments rostral to the level) or below the injury level (Bryce et al., 2012). There appears to be little or no difference in the quality of at-and below-level neuropathic pain, with both types causing sensations described by the following terms: hot-burning, tingling, pricking, like pins and needles, sharp, shooting, squeezing, painfully cold, and electric shock-like (Bryce et al., 2012). Neuropathic pain often occurs spontaneously but can also be evoked by extrinsic stimuli that are not normally painful (a type of pain called allodynia), or in exaggerated form by noxious stimuli (a type of pain called hyperalgesia). Spontaneous somatosensory sensations that are abnormal and disagreeable but not painful (dysesthesia) often occur along with neuropathic pain (Fig. 1). Mechanisms of neuropathic SCI pain have been studied primarily in rodent preclinical models (for recent reviews, see Gwak et al., 2012, Kramer et al., 2016, Walters, 2012, Walters, 2014). Very little is known about mechanisms of dysesthesia after SCI.

3.3. Central mechanisms of SCI-induced neuropathic pain

Mechanisms of neuropathic pain produced by SCI remain poorly understood, but many hypotheses have been tested in rodent models. SCI- induced changes in the balance of excitatory and inhibitory influences at any level of the pain pathway may result in neuropathic pain (Finnerup and Jensen, 2004; Whitt et al., 2013), but how such changes selectively lead to pain felt at different levels is not clear. It is particularly difficult to explain how below-level pain is generated. One possibility is that a slow buildup of hyperactivity in neurons below a lesion eventually activates whatever spinal neurons remain intact in ascending pain pathways (e.g., the spinothalamic tract) to then excite supraspinal pain circuits and drive the conscious sensation of below-level pain (Fig. 1) (Wasner et al., 2008). Prolonged input from hyperactive below-level neurons might also cause enduring higher-level alterations (Nardone et al., 2013), such as the cortical reorganization suggested as a mechanism for phantom limb pain (Flor et al., 2006). However, recent evidence suggests that chronic alterations in lower neural systems, including primary afferent neurons, may be essential for continuously driving alterations in higher-level structures that have been correlated with phantom limb pain (Makin et al., 2015; Vaso et al., 2014). Regardless of whether higher- or lower-level neural plasticity is the primary chronic driver of SCI pain, higher-level consequences (including conscious pain experience) of below-level hyperactivity are likely in many if not most cases of SCI, given the evidence for covert functional pathways remaining even after an SCI that appears clinically “complete” (Detloff et al., 2008; Finnerup et al., 2004; Wasner et al., 2008).

Hyperactivity of spinal neurons that drive ascending pain pathways (central sensitization, Fig. 1) could result from many effects of SCI. At-level activity could be generated immediately by SCI through the direct release of depolarizing agents from injured and dying cells (e.g., K+ and glutamate) (Finnerup and Jensen, 2004; Yezierski, 2009). Direct, injury-induced excitation of pain pathways should decline with time after SCI, but the intense early activity probably spreads widely in the CNS, and in some parts of pain pathways it might induce long-term synaptic alterations like those underlying memory in the brain, such as late-phase long-term synaptic potentiation (LTP) (Asiedu et al., 2011; Laferriere et al., 2011; Marchand et al., 2011; Rahn et al., 2013; Price and Inyang, 2015). Indeed, memory-like synaptic alterations have been implicated in spinal neurons after SCI, which could help to maintain chronic central sensitization and associated pain (Crown et al., 2006; Tan et al., 2008; Tan and Waxman, 2012).

Intense activation of neural pathways during SCI can also trigger persistent alterations of ion channel function and increase intrinsic excitability of neurons in spinal pain pathways (contributing to central sensitization) (Fig. 1), for example by increasing the expression of voltage-gated Na+ channel subunits such as Nav1.3 (Hains et al., 2003; Hains et al., 2005) or expression of the α2-δ1 voltage-gated Ca2+ channel subunit (Boroujerdi et al., 2011). Below-level pain after partial interruption of axonal tracts might be promoted by loss of descending inhibition onto below-level nociceptive pathways, which would increase activity by disinhibiting surviving ascending pain pathways (Fig. 1) (Bruce et al., 2002; Hains et al., 2002; You et al., 2008). Below-level behavioral hypersensitivity has also been linked to reduced activity in local GABAergic inhibitory interneurons in the spinal dorsal horn (Gwak et al., 2006; Drew et al., 2004), and to possible apoptotic loss of GABAergic neurons in lumbar segments distant from a contusion injury (Meisner et al., 2010). Interruption of ascending pain pathways might also contribute to neuropathic pain; for example, deafferentation by SCI may cause increased sensitivity of pain-related neurons in the thalamus to synaptic inputs (Wang and Thompson, 2008) and lead to activity-dependent reorganization of cortical pain networks (Nardone et al., 2013).

Neuroinflammatory mechanisms, many in microglia and astrocytes, are strongly implicated as drivers of hyperactivity in spinal pain pathways during SCI pain (Fig. 1) (Walters, 2014). SCI causes the generation and widespread release of proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., Alexander and Popovich, 2009). TNF α and IL-1β are reported to induce spinal LTP at C-fiber synapses associated with behavioral hypersensitivity, both by direct actions at these synapses (Kawasaki et al., 2008) and by indirect actions involving recurrent release of additional glial mediators (Gruber-Schoffnegger et al., 2013). Accumulating evidence indicates that neuroinflammation after SCI, like neuropathic SCI pain, persists indefinitely (Beck et al., 2010; Byrnes et al., 2011; Dulin et al., 2013; Fleming et al., 2006; Nesic et al., 2005). Interventions that reduce signaling by cells in the innate immune system, including microglia and macrophages, reduce reflex hypersensitivity after SCI, as illustrated by the following examples. Systemic injection of the potent anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10, shortly after excitotoxic spinal injury delayed and decreased SCI-induced excessive grooming, and reduced neural damage and signs of neuroinflammation (Plunkett et al., 2001). Knockout of IL-10 accelerated the onset of pain-related behavior and expansion of the lesion (Abraham et al., 2004). IL-10 delivered by a herpes simplex virus vector after spinal contusion injury decreased spinal TNF α expression and astrocyte activation, hindlimb mechanical and heat hypersensitivity, and an operant measure of evoked pain (Lau et al., 2012). A widely used but relatively non-specific inhibitor of microglial activation, minocycline, reduced signs of microglial activation, spontaneous and evoked activity in lumbar dorsal horn neurons, and reversed hypersensitivity of hindlimb reflexes following intrathecal injection one month after contusive SCI (Hains and Waxman, 2006). The proinflammatory mediators leukotriene B4 and PGE2 were found to be elevated at a spinal contusion site 9 months after injury, and treatment of rats for 1 month starting 8 months after SCI with a dual COX/5-LOX inhibitor, licofelone, to suppress their synthesis reversed mechanical hypersensitivity of the hindpaws (Dulin et al., 2013).

A major component of neuroinflammation is astrocyte activation, and several studies suggest that persistent activation of astrocytes contributes to chronic SCI pain. For example, in the CNS the gap junction protein, connexin 43 (Cx43), is primarily expressed in astrocytes (also in astrocyte-like satellite glial cells in the DRGs). Transgenic mice with deletion of Cx43 showed reduced expression of the astrocytic activation marker, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), associated with little or no mechanical or heat hypersensitivity of paw withdrawal 1–2 months after contusive SCI (Chen et al., 2012). One mechanism by which astrocytes increase neuronal activity after SCI is a reduction in glutamate uptake at active synapses caused by decreased expression of the glutamate transporter GLT1 (Watson et al., 2014). Selective overexpression of GLT1 in dorsal horn astrocytes after unilateral cervical contusion in mice reversed both reflex hypersensitivity and signs of hyperactivity in cervical dorsal horn neurons (Falnikar et al., 2016), providing strong evidence for persistently altered astrocyte function as a major contributor to chronic SCI pain.

3.4. Sensory neuronal mechanisms promoting SCI-induced neuropathic pain and AD

The proposed central mechanisms of SCI-induced pain reviewed above assume that pain is largely a direct consequence of spinal pathology on cells within central pain pathways. Another possibility is that at least some of the pain, the central neural hyperexcitability, and the glial activation observed chronically after SCI result from persistently enhanced input to spinal pain pathways from primary sensory neurons.

The first evidence suggesting enhanced sensory input after SCI was anatomical. In a variety of preclinical models of SCI, staining for the nociceptor-associated neuropeptide, calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), revealed apparent expansion of central arbors (sprouting) of unmyelinated (C-fiber) peptidergic nociceptors in the spinal dorsal horn across many segments below and, to a lesser extent, above the spinal lesion site (Fig. 1) (Christensen and Hulsebosch, 1997; Krenz and Weaver, 1998; Jacob et al., 2003; Ondarza et al., 2003; Zinck et al., 2007; Hou et al., 2009; Lee-Kubli et al., 2016). Probable SCI-induced sprouting of CGRP-expressing fibers within the dorsal horn also was reported in humans (Ackery et al., 2007). In vivo injection of agents to neutralize a secreted growth factor (Fig. 1), nerve growth factor (NGF), reduced SCI-induced expansion of CGRP-expressing arbors in the dorsal horn and also reduced pain-related behavior (Christensen and Hulsebosch, 1997) as well as AD (Krenz et al., 1999; Marsh et al., 2002). SCI enhances an intrinsic growth state in some populations of DRG neurons, including CGRP+ neurons, as revealed by increased growth of small and medium-sized but not large DRG neurons dissociated from ganglia below and at but not above a thoracic contusion site (Bedi et al., 2012). Substance P, which is expressed by some nociceptors, did not show increased spinal immunoreactivity after SCI (Marsh and Weaver, 2004). While CGRP and substance P are both considered to be characteristic of the peptidergic class of nociceptors, many CGRP-expressing DRG neurons fail to co-express detectable substance P (Price and Flores, 2007; Hsieh et al., 2012), which suggests that primarily the peptidergic subpopulation lacking substance P sprouts after SCI. Two studies using a complete transection SCI model or a clip-compression injury in rats showed the opposite effect above a T13 injury level: reduction rather than any increase in CGRP staining (Kalous et al., 2007). However, increased CGRP staining rostral to the spinal injury level has been reported in other SCI models, including spinal hemisection at T13 (Christensen and Hulsebosch, 1997) and severe compression or transection at T3 (Lee-Kubli et al., 2016). This apparent discrepancy in the evidence for above-level sprouting is not understood, but it indicates that nociceptor sprouting depends upon complex interactions among factors related to the nature, severity, and level of spinal injury. Importantly, if sprouting of peptidergic nociceptors results in the formation of aberrant synapses within the spinal cord that enhance or broaden the range of stimuli that elicit sympathetic reflexes, then this sprouting would likely be an important mechanism contributing to AD (Fig. 1) (Krenz and Weaver, 1998; Rabchevsky, 2006). This possibility is supported by multiple lines of evidence (Krenz et al., 1999; Marsh et al., 2002; Brown et al., 2004; Cameron et al., 2006; Hou et al., 2009).

SCI was later found to enhance the sensitivity and firing of C-fiber nociceptors, both in peripheral terminals and in the cell soma within the DRG (Fig. 1). Cutaneous sensitivity to mechanical and heat stimuli was increased in a rat forepaw skin-nerve preparation 5 weeks after contusion at the vertebral T10 level (Carlton et al., 2009). This study also found that spontaneous electrical activity (SA) was generated at a low rate in the peripheral terminals of C-fiber nociceptors after SCI. SCI-induced SA is also generated in or near the cell bodies (somata) of numerous C-nociceptors and some Aδ nociceptors in vivo (Bedi et al., 2010). The most extensive analyses have been conducted on intrinsic SA and hyperexcitability recorded in small dissociated DRG neurons, often capsaicin-sensitive C-nociceptors (see below). SA was found in ~50% of small neurons dissociated from DRGs below and at (but not above) the injury level, and the high incidence of SA (Nthan three times the incidence found in neurons from naïve or sham-operated animals) remained unchanged for at least 5 months after SCI (Bedi et al., 2010). This intrinsic SA in isolated nociceptors was correlated with behavioral indications of pain and/or spasticity tested in the same rats: mechanical and heat hypersensitivity of hindlimb and forelimb withdrawal responses, as well as an increased incidence of a supraspinally mediated response, vocalization. Interestingly, vocalization after SCI was evoked at but not below the injury level (Bedi et al., 2010) – a pattern like that reported in humans whose SCI has largely interrupted ascending pain pathways (Finnerup et al., 2014).

Several findings indicate that hyperactivity in primary nociceptors below and at a spinal injury level contributes to chronic pain after SCI (Fig. 1). Many nociceptors express the transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, TRPV1 and/or TRPA1, and the vast majority of TRPA1-expressing DRG neurons coexpress TRPV1 (Story et al., 2003; Bautista et al., 2006). Most of the dissociated DRG neurons showing SA after SCI in rats were found to be responsive to the specific TRPV1 activator, capsaicin (Bedi et al., 2010). TRPV1 expression, a month or more after thoracic contusion, was increased in lumbar DRGs (Wu et al., 2013) (see also DomBourian et al., 2006; Ramer et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2002) as well as in the spinal dorsal horn (Wei et al., 2016). Very low concentrations of capsaicin (10 nM) produced non-desensitizing, non- accommodating repetitive firing in dissociated nociceptors that was indistinguishable from SCI-induced SA, and this effect and other cellular responses to capsaicin were enhanced after SCI (Wu et al., 2013). Importantly, SCI-induced mechanical and heat hypersensitivity of hindlimb withdrawal responses were reversed by antisense knockdown of TRPV1 or by systemic injection of specific TRPV1 antagonists (Wu et al., 2013) (see also Rajpal et al., 2007; Wei et al., 2016). While TRPV1 channels have been observed in other cells, they are expressed most abundantly in nociceptors (Caterina et al., 2000; Lauria et al., 2006), consistent with the possibility that reduction of nociceptor hyperactivity contributed to these suppressive effects. TRPA1 function also has been implicated in maintaining SCI pain. Expression of TRPA1 mRNA in DRG neurons increased for at least a week after contusive SCI, along with elevation of one of its activators, the inflammatory lipid product acrolein, in the spinal cord (Due et al., 2014). Another study found that TRPA1 protein expression increased in the spinal cord (likely in nociceptor terminals), and that intrathecal injection of a TRPA1 antagonist decreased hindlimb reflex hypersensitivity after contusive SCI (Wei et al., 2016). Note that numerous TRPV1- and TRPA1-expressing C-nociceptors have cell bodies in DRGs and innervate visceral organs. Sensitization of these sensory neurons (e.g., Chen et al., 2013) could potentially contribute to the visceral pain that sometimes follows SCI (Fig. 1).

An unexpectedly large role for nociceptor activity in maintaining pain after contusive SCI in rats was revealed when antisense knockdown of a voltage-gated Na+ channel, Nav1.8, eliminated SCI-induced SA and reversed reflex hypersensitivity – which could reflect evoked pain and/or unconscious hyperreflexia (Fig. 1) (Yang et al., 2014). This provided strong evidence for a requirement of nociceptor activity because Nav1.8 is expressed almost exclusively in primary somatosensory neurons, including N90% of C-nociceptors (Liu and Wood, 2011; Shields et al., 2012). Nav1.8 protein expression increased for at least a month after SCI, without a change in mRNA expression (Yang et al., 2014). Importantly, knockdown of Nav1.8 also eliminated an operant measure of spontaneous pain (Fig. 1) – conditioned place preference (CPP) for a chamber paired with injection of an analgesic agent, retigabine, which did not produce CPP in sham-operated or naïve rats (Wu et al., 2017). Hyperexcitability of C-nociceptors after SCI probably depends upon altered expression and/or activity of multiple ion channels, including reduced function of K+ channels (Bedi et al., 2010; Ritter et al., 2015) as well as enhanced function of Na+ channels. Persistently altered ion channel function after SCI appears to depend in part upon continuing cAMP signaling, as SCI-induced SA in nociceptors dissociated from DRGs taken from SCI animals was eliminated by specific blockers acting at each step along the AKAP-linked pathway from adenylyl cyclase to PKA (Bavencoffe et al., 2016).

TRPV1 and TRPA1 have important roles in host defense, being activated and/or sensitized by many features of inflammation, including acidity, numerous lipids generated during cellular injury or ischemia, and/or a growing number of other injury-related molecules (e.g., amines, ATP, NO, reactive oxygen species, MCP-1) (Jung et al., 2008; Morales-Lazaro et al., 2013; Miyamoto et al., 2009; Nishio et al., 2013; Bautista et al., 2006; Dai, 2016; Nilius et al., 2012). Thus, after SCI, chemosensitive DRG neurons, through these and other receptors, may detect multiple signs of inflammation both peripherally and in the spinal cord. Furthermore, within the DRGs, cell bodies of primary nociceptors may play a major role in detecting inflammatory signals and integrating them with other signals of serious bodily injury that are released by SCI (Walters, 2012), especially when SCI causes an up-regulation of receptors for these inflammatory signals in at-level and below-level nociceptor somata (chemical sensitization, Fig. 1) (Wu et al., 2013; Due et al., 2014; Wei et al., 2016). Interestingly, NE administration to dissociated nociceptors has been found to increase TRPV1 expression (Zhu et al., 2015), suggesting that sympathetic activity might contribute to chemical hypersensitivity in nociceptors. Pain-promoting sensitization of DRG neurons has been shown to occur after experimental inflammation around a ganglion (Wang et al., 2007; Xie et al., 2006), which causes upregulation of TRPV1 in nociceptors and the generation of numerous cytokines in the DRG (Dong et al., 2012; Strong et al., 2012; Xie et al., 2016). After SCI, nociceptor somata come into contact with macrophages and T cells that infiltrate into DRGs close to and distant from a spinal lesion (McKay and McLachlan, 2004). The vascular permeability barrier in DRGs is much less effective than the blood-brain or blood-nerve barriers (Abram et al., 2006; Jimenez-Andrade et al., 2008) so that neurons and satellite glial cells in DRGs are uniquely exposed both to blood and cerebrospinal fluid along the spinal column. This means that cytokines and chemokines released after SCI are readily available to cells in DRGs, including satellite glial cells, that may be activated to produce neuroinflammation within these ganglia (Fig. 1) (Blum et al., 2014; Cheng et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2013; Ramer et al., 1999). This also means that nociceptor somata are directly exposed to elevated levels of neuroactive cytokines, some of which have been reported to increase in the blood and/or CSF of SCI patients (Davies et al., 2007; Stein et al., 2013; Kwon et al., 2010). One interesting example is macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF), which has a circulating concentration that is normally ~1000 fold higher than other pro-inflammatory cytokines (Calandra and Roger, 2003; Bucala, 1996; Aloisi et al., 2005), and this concentration was doubled in SCI patients compared to uninjured controls (Stein et al., 2013). This concentration of MIF, ~1 ng/ml, was also found to increase the excitability of small sensory neurons isolated from mouse DRGs (Alexander et al., 2012). The finding that MIF-null mice failed to develop pain after nerve injury or hindpaw inflammation in this study, along with complementary findings in rats (Wang et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2011a), raise the possibility that pain in SCI patients might be promoted by chronic elevation of circulating MIF that directly excites primary nociceptors.

While growing preclinical evidence supports the hypothesis that an SCI-induced enhancement of function in primary nociceptors (involving hyperexcitability, SA, chemical hypersensitivity, and perhaps synaptic growth) contributes to neuropathic SCI pain and possibly AD (Fig. 1), this hyperfunctional nociceptor hypothesis has yet to be tested in humans. One prediction that needs to be confirmed in rodent SCI models and tested in humans is that SCI leads to the generation of SA within the cell bodies (somata) of C-nociceptors in DRGs recorded in vivo. While many studies in animals and humans record sensory activity from peripheral axons in vivo, and a number of rodent studies have recorded sensory activity in excised dorsal root-DRG-nerve preparations, very few studies have recorded activity in vivo under conditions where the generation of activity can be localized to the DRG and (unlike the excised DRG preparations) where DRG neurons are exposed to circulating factors that may contribute to somally-generated SA, especially in chemically sensitized DRG neurons. Furthermore, given the importance of SA in Aβ low-threshold mechanoafferent neurons (A-LTMs) in several peripheral neuropathic pain models (see below), another unanswered question is whether hyperfunctional alterations also occur in A-LTMs, which could contribute to allodynia and dysesthesia (Fig. 1). Limited data suggest that SCI-induced enhancement of both SA recorded in vivo (Bedi et al., 2010) and intrinsic growth states (Bedi et al., 2012) are greater in C-nociceptors than in A-LTMs, but few A-LTMs have been sampled during in vivo experiments examining SCI-induced SA, and A-LTM sprouting into the spinal cord after SCI does not appear to have been investigated.

4. Functional relationships between sympathetic and pain systems

Before explicitly considering potential links between AD and chronic neuropathic pain induced by SCI, it is useful to point out areas both of functional overlap and apparent conflict between the sympathetic nervous system (which produces each AD episode) and pain. The sympathetic nervous system is generally considered an efferent system that directly regulates diverse tissues with little or no conscious awareness. In contrast, according to the widely accepted taxonomy of the International Association for the Study of Pain, pain is defined as conscious emotional awareness of sensory information about actual or potential tissue damage – i.e., pain is an often intensely unpleasant feeling about noxious events sensed somewhere on or in the body. Both the sympathetic nervous system and pain system have important protective functions. Acute pain is protective because it serves as a warning about incipient tissue injury, while longer-lasting pain during recuperation can protect against further injury or infection by minimizing movement of an injured body part or contact of the body part with threatening objects (Walters, 1994). The sympathetic nervous system has long been known to be preeminent in rapidly mobilizing the body’s defenses during physiological emergencies or in the face of significant threats, working along with the adrenal system (e.g., Goldstein and Kopin, 2007) and central noradrenergic systems (Pertovaara, 2013; Schwarz and Luo, 2015). The onset of tissue injury is potentially a grave threat, so one of the many types of stimuli that activate protective sympathetic reflexes is input to the central nervous system from nociceptors (Burton et al., 2016; Janig, 2014). Under normal conditions nociceptor activity leads to the conscious experience of pain (Bromm and Treede, 1984; Van Hees and Gybels, 1972; Wiesenfeld-Hallin et al., 1984). However, the relationship between nociceptor activity, sympathetic activity, and pain is complicated because highly threatening stimuli that strongly activate the sympathetic nervous system, such as the approach of a predator or an aggressive antagonist, usually inhibit pain (Wall, 1979; Walters, 1994). Thus, even though nociceptors may be intensely activated by injuries sustained while struggling with or escaping an assailant, conscious pain and pain-associated recuperative behavior are suppressed acutely by powerful central mechanisms that operate at multiple levels in the pain pathway to inhibit transmission of nociceptive information to the brain until major threats have passed (Melzack and Wall, 1965; Ossipov et al., 2010; Treede, 2016). Interestingly, sympathetic activation and peripheral norepinephrine (NE) release are associated with activation of noradrenergic neurons within the CNS, the activation of which increases arousal and alertness (Schwarz and Luo, 2015). In contrast to some of NE’s peripheral hyperalgesic effects (see below), its central actions are primarily analgesic. Indeed, centrally acting α2-adrenergic agonists such as clonidine are effective analgesics (Ossipov et al., 2010). These opposite effects of central and peripheral NE complicate efforts to treat pain by targeting noradrenergic transmission.

Serious injury will be followed by a lengthy period of recuperation and inactivity. During the recuperative phase, the intense, widespread sympathetic activity that had driven the diverse components of the “fight-or-flight” response will have shut down, and ongoing pain and painful hypersensitivity (hyperalgesia and allodynia) become prominent. This phase is thought to be driven by continuing activity of nociceptors innervating injured tissue—particularly deep tissue—and by pro-inflammatory cytokines acting on somatic nociceptors, visceral afferents (vagal and DRG C-fibers), and circumventricular organs in the brain (Watkins and Maier, 2000; Janig, 2014). Importantly, low levels of widespread sympathetic activity continue during recuperation, and higher levels of activity may occur in selected sympathetic postganglionic neurons intermittently during autonomic reflexes (Janig, 2014). This continuing sympathetic activity has long been implicated as a significant contributor to the maintenance of many chronic pain states (Borchers and Gershwin, 2014; Drummond, 2013; Mantyh, 2014; Schlereth et al., 2014). Indeed, local sympathetic block and sympathetic lesions are widely used to treat painful conditions such as complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), phantom limb pain, cancer pain, postherpertic neuralgia, and ischemic pain (Abramov, 2014; Agarwal-Kozlowski et al., 2011; Mercadante et al., 2015). However, the clinical effectiveness of sympathetic interventions has yet to be demonstrated conclusively. Relatively few clinical trials have been run, these have yielded mixed results, and most have been limited by small size and often a lack of placebo controls, randomization, effective blinding, and/or adequate outcome measures (Abramov, 2014, Dworkin et al., 2013, Zernikow et al., 2015, O’Connell et al., 2016).

5. Interactions among sympathetic activity, innate immune function, and DRG neurons

As discussed above, chronic pain after SCI appears to be driven, at least in part, by central and peripheral neuroinflammation, and by increased activity and possibly aberrant synapse formation by primary nociceptors. These sensory alterations might both result from and promote neuroinflammation, with this positive feedback relationship helping to maintain SCI pain persistently (Fig. 1) (Walters, 2012; Walters, 2014). Increasing evidence indicates that aspects of inflammation and related sensory neuron function are regulated by the sympathetic nervous system in ways that might contribute to chronic pain and AD after SCI. However, these interactions are quite complex (Fig. 1). It has long been known that sympathetic activity has suppressive effects on both adaptive immunity (Webster et al., 2002) and on innate immunity and inflammation (Padro and Sanders, 2014; Scanzano and Cosentino, 2015). Indeed, patients with high SCI are immune compromised and inordinately susceptible to infection, in part because of sympathetically mediated suppression of systemic immune function (Zhang et al., 2013; Lucin et al., 2009; Lucin et al., 2007) involving plastic reorganization of spinal autonomic circuitry below the injury level that greatly enhances a sympathetic anti-inflammatory reflex (Fig. 1) (Ueno et al., 2016; Weaver et al., 1997; Deuchars, 2015). These systemic immune suppressive effects after SCI are quite large and depend in part upon NE released from sympathetic postganglionic terminals in the spleen, which activate β2 adrenergic receptors to reduce lymphocyte function and survival (Lucin et al., 2009; Lucin et al., 2007).

On the other hand, sympathetic stimulation can also have pro-inflammatory actions in some contexts on immune cells and on other cells that release inflammatory mediators, such as keratinocytes and satellite glial cells (for interesting insight into pain-related cytokines in these cells, see Kingery, 2010, Tse et al., 2014). For example, sympathetic stimulation can upregulate α 1 adrenergic receptors, which produce many effects opposite to those of β2 receptor stimulation in these cells (Bellinger and Lorton, 2014; Schlereth et al., 2014). Furthermore, by activating peptidergic nociceptors (see below), sympathetic stimulation can enhance neurogenic inflammation (Wang et al., 2004), which is mediated by release of the neuropeptides CGRP and substance P from peripheral terminals of these sensory neurons (Birklein and Schmelz, 2008; Sann and Pierau, 1998), and possibly within the DRG (Huang and Neher, 1996; Zhang and Zhou, 2002). An unexpected and important recent discovery was that more restricted inflammation involving a small number of DRGs that drives pain hypersensitivity in rats depends upon ongoing local sympathetic activity (Xie et al., 2016). This study utilized a “microsympathectomy,” unilaterally cutting the L4 and L5 gray rami to selectively ablate sympathetic post-ganglionic fibers that innervate L4 and L5 DRGs as well as hindlimb targets innervated by L4 and L5 spinal nerves. This intervention left intact the sympathetic innervation of most primary immune tissues, the spleen, and the adrenal glands. It dramatically reduced allodynia produced by experimental inflammation (injection of complete Freund’s adjuvant) of skin on the hindpaw along with inflammatory swelling of the paw and macrophage staining within the paw. L4/L5 microsympathectomy also had profound effects on the responses of the L4 and L5 DRGs to local inflammation produced by zymosan injected into the L5 intervertebral foramen. It blocked almost completely both the development and maintenance of allodynia that results from DRG inflammation while decreasing inflammation-induced macrophage staining in the DRG. This was accompanied by significant decreases in the elevation produced by the local inflammatory stimulus of Type 1 (primarily pro-inflammatory) cytokines, including MCP-1, IL-6, IL-1a, IL1-b, IL-18, and MIP-1a. It was also accompanied by decreases in the Type 2 (largely anti-inflammatory) cytokines IL-4, IL-12p70, and eotaxin. These findings provide strong evidence for the DRG as an important site at which sympathetic activity enhances pain by promoting local inflammation (Fig. 1).

The mechanisms underlying the promotion of persistent pain by sympathetic activity involve complicated interactions between postganglionic sympathetic neurons and primary somatosensory neurons (Fig. 1) – both larger, low-threshold Aβ DRG neurons (A-LTMs) and nociceptive C and Aδ DRG neurons. These interactions have been studied preclinically in rat DRGs, where sympathetic fibers normally are restricted to blood vessels and rarely come close to the neurons – although the fibers may nevertheless come close enough to directly or indirectly influence DRG neuron function (Xie et al., 2016). Interestingly, several persistent pain models (peripheral nerve transection, spinal nerve ligation, chronic constriction injury of sciatic nerve, local inflammation of the DRG) induce sprouting of sympathetic fibers into DRGs, where they often form ring- or basket-like structures around large (Aβ) and medium-sized (Aδ) neuronal somata (Chien et al., 2005; McLachlan et al., 1993; Ramer and Bisby, 1997; Xie et al., 2006; Xie et al., 2015). This sprouting depends upon action potentials as it is prevented by blocking activity coming from a nerve injury site (Xie et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2004) or by DRG-selective knockdown of a voltage-gated Na+ channel (Nav1.6) preferentially expressed in larger DRG neurons (Xie et al., 2015). Moreover, sprouting is increased by non-selectively enhancing electrical activity in the peripheral nerve (Xie et al., 2007). In the spinal nerve ligation model, basket-like structures of sympathetic sprouts were found primarily around Nav1.6-expressing neurons, suggesting that electrical activity in A-LTMs neurons is directly or indirectly responsible for attracting sympathetic sprouts (Fig. 1) (Xie et al., 2015). Knockdown of Nav1.6 in the DRG also blocked SA in A-LTMs and reduced allodynia (Xie et al., 2013; Xie et al., 2015), which suggest that allodynia and perhaps spontaneous dysesthesia can be promoted by either direct or indirect sympathetic actions on A-LTMs (Fig. 1). In at least two rat peripheral neuropathic pain models, cuff compression and spared nerve injury, reinnervation of plantar skin by nociceptive and low threshold sensory fibers was associated with sprouting of sympathetic fibers into the skin, suggesting that more peripheral sympathetic sprouting might also enhance sensory function (Nascimento et al., 2015).

What are the consequences of sympathetic activity on sensory neuron function? Under normal conditions, sympathetic stimulation in rodent preclinical models does not activate DRG neurons, but in vivo stimulation of sympathetic fibers after peripheral nerve injury can excite both Aβ fibers (Devor and Janig, 1981; Devor et al., 1994; Michaelis et al., 1996) and C fibers (Habler et al., 1987; Hu and Zhu, 1989; Sato and Perl, 1991; Sato et al., 1993), and these effects depended at least in part on α adrenergic receptors (especially α2 receptors) (Sato and Perl, 1991; Sato et al., 1993; Chen et al., 1996). In humans, application of NE or α adrenergic agonists to uninjured human skin has been reported to produce no pain (Zahn et al., 2004), but also to sensitize responses to painful heat stimuli (Drummond, 1995; Drummond and Lipnicki, 1999; Fuchs et al., 2001). Iontophoresis of NE into skin of human volunteers after topical treatment with capsaicin enhanced spontaneous pain and mechanical and heat hyperalgesia, suggesting that under some sensitizing conditions NE can further enhance nociceptor sensitivity and SA (Schattschneider et al., 2007). Indeed, in a subset of patients with entrapment of the median nerve who were hyperalgesic to heat, both sympathetic stimulation (by cooling) and NE iontophoresis significantly worsened the hyperalgesia (Schattschneider et al., 2008). Injection of the adrenomedullary stress hormone, epinephrine (functionally and chemically closely related to NE) near a neuroma was reported to produce intense pain (Chabal et al., 1992). However, in patients with painful polyneuropathy no evidence for sensitization to cutaneous iontophoresis of NE was found (Schattschneider et al., 2006), nor was evidence found for peripheral activation of C-fiber nociceptors by sympathetic activity in patients with CRPS (Campero et al., 2010)—in contrast to a report of sympathetic and noradrenergic activation of C fibers in a single patient with sympathetically maintained pain (Jorum et al., 2007). Thus, the conditions in which sympathetic activity excites primary sensory neurons in humans are not well understood.

In rodent preclinical models, mechanisms of sympathetic excitation of DRG neurons have been investigated using simplified preparations. Relatively high concentrations of NE were found to excite dissociated small and medium-sized DRG neurons from rats with prior nerve, dorsal root, or DRG injury, but not neurons from uninjured rats (Petersen et al., 1996; Hu et al., 2000; Tanimoto et al., 2011). Recordings from the dorsal root attached to an excised DRG preparation taken from rats with chronic constriction injury of the sciatic nerve revealed that C, Aδ, and Aβ neurons responded to NE and to an α2 receptor agonist applied topically to the DRG (Zhang et al., 1997). NE activation of α receptors in peptidergic nociceptors has also been reported to enhance the release of substance P (Wang et al., 2011c). Note that these studies rarely distinguished direct effects of NE from indirect effects mediated by other cell types in the ganglion or possibly even in the culture dish. Additional findings show that β adrenergic receptors can excite DRG neurons. For example, β2 receptor antagonists blocked DRG neuron hyperexcitability and visceral hypersensitivity induced by NE administration or stress in a model of irritable bowel syndrome (Zhang et al., 2014). Some C-nociceptors innervate visceral organs and sensitization of these sensory neurons (Winston et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2015; Gil et al., 2016) could potentially contribute to the visceral pain that sometimes follows SCI (Fig. 1). The β receptor agonist isoproterenol potentiated tetrodotoxin-resistant Na+ current (likely Nav1.8-mediated) in dissociated nociceptors (revealing a direct effect), as well as producing cutaneous hyperalgesia (Khasar et al., 1999). This study and others (Ochoa-Cortes et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2011b) found excitatory or sensitizing effects of epinephrine on nociceptors, which depended upon β adrenergic receptors. Whether epinephrine released under stressful conditions contributes to pain- or AD-related functions of DRG neurons after SCI does not appear to have been reported.

6. Functional model for the promotion of SCI-induced pain and AD by interactions among sympathetic activity, innate immune function, and hyperfunctional sensory neurons

A set of interactions that can, in principle, drive AD and pain-related alterations after severe, high (above T5) SCI are schematized in the preliminary functional model shown in Fig. 1. These interactions are physiologically plausible and most have received some experimental support, as discussed throughout this article (for published references supporting each element, see references in the passages above that cite Fig. 1). However, much of this support is indirect, often coming from experimental models other than SCI. Thus, this speculative “sympathetic-inflammation-DRG-pain-AD” model is intended to organize intriguing observations and spur further research. While the model applies to AD and to at least part of the at-level pain (spontaneous pain, hyperalgesia, allodynia) and dysesthesia following complete or incomplete SCI, it does not explain below-level pain after complete SCI (which is unlikely to be explained solely by below-level and at-level mechanisms). The core idea of this model is that inflammatory and anatomical consequences of severe SCI lead to persistent sensitization of at-level and below-level spinal networks (sympathetic and pain-related circuits) that is sustained, in part, by ongoing activity in DRG neurons. Importantly, as evident in Fig. 1, many of the critical interactions are mutually facilitatory, resulting in positive feedback loops that should help perpetuate the sensitization.

The model assumes that SCI initiates sensitizing alterations primarily by removal of descending influences on below-level spinal circuitry and by mediators released during neuroinflammatory and systemic inflammatory reactions to the injury. Loss of descending excitation of sympathetic preganglionic neurons in the spinal intermediolateral column reduces basal sympathetic tone (reflected by resting hypotension) but this reduction in tonic activity also may help to sensitize sympathetic pathways to sporadic reflexive stimuli by allowing an increased surface expression of excitatory receptors (receptor supersensitization) in pre- and postganglionic neurons and in peripheral target cells. This prediction assumes that sensitizing effects on surface expression from reduction in tonic, background sympathetic activity outweigh the temporary desensitizing effects on receptors of relatively infrequent but intense sympathetic reflex activation, as in AD episodes. In contrast, the predominant consequence of loss of descending influences on pain-related circuitry in the spinal dorsal horn (DH) is assumed to be from removal of inhibitory input, resulting in central sensitization from disinhibition (excitation) of many excitatory dorsal horn neurons (DHN) in the pain pathway. Intensely excited DHNs might release retrograde synaptic signals that are detected by presynaptic sensory neurons and integrated with other injury- and inflammation-related signals to help trigger a hyperfunctional state in some of the sensory neurons.

Severe damage to the spinal cord (and nearby tissues) will release innumerable damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs or “danger signals”) that stimulate extensive spinal neuroinflammatory and systemic inflammatory responses that, in turn, excite or sensitize spinal neurons. Some DAMPs (e.g., glutamate, ATP, HMGB1) can also directly trigger plastic alterations in neurons without intercession by inflammatory cells. DAMPs and inflammatory signals stimulate spinal production of growth factors (notably, NGF) that promote the sprouting of C-fiber nociceptors into regions of the spinal cord where they may make new synapses onto excitatory interneurons that can drive sympathetic re-flexes and/or pain (contributing to central sensitization). Loss of descending axons plus the production of various growth factors with consequent sprouting or remodeling of sensory neuronal and possibly interneuronal synaptic processes contribute to the reorganization of spinal sympathetic circuitry that sensitizes sympathetic reflexes.

Release of pro-inflammatory signals (e.g., chemokines such as MCP-1) into the cerebrospinal fluid after SCI is postulated to trigger neuroinflammation in both at-level and below-level DRGs that involves activation of satellite glial cells and infiltration of macrophages. Indeed, inflammatory signals from three sources (spinal cord, DRG, and blood) are postulated to bind to receptors on numerous at-level and below-level C-nociceptors (and possibly Aδ nociceptors – not shown) and on some A-LTMs, triggering persistent hyperexcitability and SA. C-nociceptors also show chemical sensitization via upregulation of TRPV1, TRPA1, and probably other receptors to DAMPs and inflammatory mediators. The resulting hyperactivity in A-LTMs and C-nociceptors promotes the sprouting of sympathetic fibers into the DRG. During sympathetic reflexes, these fibers release NE (and perhaps co-transmitters) into the ganglion to further excite and/or sensitize C-nociceptors and A-LTMs. In addition, the activity of sympathetic fibers in the DRG may help maintain inflammation locally within the DRG, with consequent production of inflammatory mediators playing a large role in exciting and sensitizing DRG neurons.

When sensitized after SCI, sensory neurons are activated more intensely by their adequate stimuli, and this, along with central sensitization of downstream targets, enhances evoked responses, including sympathetic reflexes (AD and systemic sympathetic immunosuppressive reflexes), somatic reflexes (e.g., withdrawal reflexes), and evoked pain (hyperalgesia felt during stimulation of C-nociceptors and possibly Aδ nociceptors, and allodynia felt during A-LTM stimulation). In contrast to the sympathetic pathways, which display sensitization but a reduction in ongoing activity (decreased tone), pain pathways show both sensitization and increased ongoing activity. This ongoing activity (SA), generated spontaneously by intrinsic mechanisms within sensory neuron cell bodies and, as a result of hypersensitivity to injury-related humoral signals (chemical sensitization), is likely to contribute to spontaneous pain after SCI. The ability of spontaneously active C-nociceptors to activate pain pathways sufficiently to drive spontaneous pain is likely to be facilitated by the partial loss of descending inhibitory influences on pain pathways caused by SCI. An interesting question is whether many of the spontaneously active C-nociceptors that continuously drive pain pathways also excite spinal sympathetic pathways. If so, this background excitation would not be amplified by the lesion-induced disinhibition postulated for spinal pain pathways, and presumably the low spontaneous firing rates in these C-nociceptors would be insufficient to offset the loss of descending tonic excitation of sympathetic pathways resulting from the lesion. Thus, in combination with central sensitization, C-nociceptors that have become hyperexcitable, chemically hypersensitive, and spontaneously active, and that may have formed new synaptic connections to spinal targets, could make a major contribution to AD (and related systemic immunosuppressive reflexes), evoked pain, visceral pain, and spontaneous pain, without effectively offsetting the loss of background sympathetic tone that typically follows high SCI. In addition, A-LTMs that have become hyperexcitable and spontaneously active after SCI could drive the sensations of allodynia and dysesthesia. Because of the many potent interactions of C-nociceptors with other components of this model, clinical interventions selectively targeting hyperactivity in C-nociceptors (such as administration of specific Nav1.8 antagonists) might be useful for treating both chronic pain and AD after high SCI.

Acknowledgments

The author’s scholarship and research while preparing this article were supported by grants RO1NS091759 from the NIH and W81XWH-15-1-0702 from the Department of Defense.

References

- Abraham KE, McMillen D, Brewer KL. The effects of endogenous interleukin-10 on gray matter damage and the development of pain behaviors following excitotoxic spinal cord injury in the mouse. Neuroscience. 2004;124:945–952. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abram SE, et al. Permeability of injured and intact peripheral nerves and dorsal root ganglia. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:146–153. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200607000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramov R. Lumbar sympathetic treatment in the management of lower limb pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2014;18:403. doi: 10.1007/s11916-014-0403-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackery AD, Norenberg MD, Krassioukov A. Calcitonin gene-related peptide immunoreactivity in chronic human spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:678–686. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3102020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal-Kozlowski K, et al. Interventional management of intractable sympathetically mediated pain by computed tomography-guided catheter implantation for block and neuroablation of the thoracic sympathetic chain: technical approach and review of 322 procedures. Anaesthesia. 2011;66:699–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JK, Popovich PG. Neuroinflammation in spinal cord injury: therapeutic targets for neuroprotection and regeneration. Prog Brain Res. 2009;175:125–137. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(09)17508-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JK, et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) is essential for inflammatory and neuropathic pain and enhances pain in response to stress. Exp Neurol. 2012;236:351–362. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aloisi AM, et al. Gender-related effects of chronic non-malignant pain and opioid therapy on plasma levels of macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) Pain. 2005;115:142–151. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andresen SR, et al. Pain, spasticity and quality of life in individuals with traumatic spinal cord injury in Denmark. Spinal Cord. 2016;54:973–979. doi: 10.1038/sc.2016.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asiedu MN, et al. Spinal protein kinase M zeta underlies the maintenance mechanism of persistent nociceptive sensitization. J Neurosci. 2011;31:6646–6653. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6286-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista DM, et al. TRPA1 mediates the inflammatory actions of environmental irritants and proalgesic agents. Cell. 2006;124:1269–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavencoffe A, et al. Persistent electrical activity in primary nociceptors after spinal cord injury is maintained by Scaffolded adenylyl cyclase and protein kinase a and is associated with altered adenylyl cyclase regulation. J Neurosci. 2016;36:1660–1668. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0895-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck KD, et al. Quantitative analysis of cellular inflammation after traumatic spinal cord injury: Evidence for a multiphasic inflammatory response in the acute to chronic environment. Brain. 2010;133:433–447. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedi SS, et al. Chronic spontaneous activity generated in the somata of primary nociceptors is associated with pain-related behavior after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2010;30:14870–14882. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2428-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedi SS, et al. Spinal cord injury triggers an intrinsic growth-promoting state in nociceptors. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29:925–935. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellinger DL, Lorton D. Autonomic regulation of cellular immune function. Auton Neurosci. 2014;182:15–41. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birklein F, Schmelz M. Neuropeptides, neurogenic inflammation and complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) Neurosci Lett. 2008;437:199–202. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.03.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum E, et al. Systemic inflammation alters satellite glial cell function and structure. A possible contribution to pain. Neuroscience. 2014;274:209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchers AT, Gershwin ME. Complex regional pain syndrome: a comprehensive and critical review. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:242–265. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boroujerdi A, et al. Calcium channel alpha-2-delta-1 protein upregulation in dorsal spinal cord mediates spinal cord injury-induced neuropathic pain states. Pain. 2011;152:649–655. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromm B, Treede RD. Nerve fibre discharges, cerebral potentials and sensations induced by CO2 laser stimulation. Hum Neurobiol. 1984;3:33–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A, Ricci MJ, Weaver LC. NGF message and protein distribution in the injured rat spinal cord. Exp Neurol. 2004;188:115–127. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce JC, Oatway MA, Weaver LC. Chronic pain after clip-compression injury of the rat spinal cord. Exp Neurol. 2002;178:33–48. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.8026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryce TN, et al. International spinal cord injury pain classification: part I. Background and description. Spinal Cord. 2012;50:413–417. doi: 10.1038/sc.2011.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucala R. MIF re-discovered: pituitary hormone and glucocorticoid-induced regulator of cytokine production. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1996;7:19–24. doi: 10.1016/1359-6101(96)00008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton AR, Fazalbhoy A, Macefield VG. Sympathetic responses to noxious stimulation of muscle and skin. Front Neurol. 2016;7:109. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2016.00109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrnes KR, et al. Delayed inflammatory mRNA and protein expression after spinal cord injury. J Neuroinflammation. 2011;8:130. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calandra T, Roger T. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor: a regulator of innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:791–800. doi: 10.1038/nri1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron AA, et al. Genetic manipulation of intraspinal plasticity after spinal cord injury alters the severity of autonomic dysreflexia. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2923–2932. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4390-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campero M, et al. A search for activation of C nociceptors by sympathetic fibers in complex regional pain syndrome. Clin Neurophysiol. 2010;121:1072–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlton SM, et al. Peripheral and central sensitization in remote spinal cord regions contribute to central neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury. Pain. 2009;147:265–276. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, et al. Impaired nociception and pain sensation in mice lacking the capsaicin receptor. Science. 2000;288:306–313. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5464.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabal C, et al. Pain response to perineuromal injection of normal saline, epinephrine, and lidocaine in humans. Pain. 1992;49:9–12. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90181-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, et al. Adrenoreceptor subtype mediating sympathetic-sensory coupling in injured sensory neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:3721–3730. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.6.3721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MJ, et al. Astrocytic CX43 hemichannels and gap junctions play a crucial role in development of chronic neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury. Glia. 2012;60:1660–1670. doi: 10.1002/glia.22384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Winston JH, Sarna SK. Neurological and cellular regulation of visceral hypersensitivity induced by chronic stress and colonic inflammation in rats. Neuroscience. 2013;248:469–478. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng CF, et al. Mirror-image pain is mediated by nerve growth factor produced from tumor necrosis factor alpha-activated satellite glia after peripheral nerve injury. Pain. 2014;155:906–920. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien SQ, et al. Sympathetic fiber sprouting in chronically compressed dorsal root ganglia without peripheral axotomy. J Neuropathic Pain Symptom Palliation. 2005;1:19–23. doi: 10.1300/J426v01n01_05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen MD, Hulsebosch CE. Spinal cord injury and anti-NGF treatment results in changes in CGRP density and distribution in the dorsal horn in the rat. Exp Neurol. 1997;147:463–475. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crown ED, et al. Increases in the activated forms of ERK 1/2, p38 MAPK, and CREB are correlated with the expression of at-level mechanical allodynia following spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2006;199:397–407. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y. TRPs and pain. Semin Immunopathol. 2016;38:277–291. doi: 10.1007/s00281-015-0526-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies AL, Hayes KC, Dekaban GA. Clinical correlates of elevated serum concentrations of cytokines and autoantibodies in patients with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88:1384–1393. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detloff MR, et al. Remote activation of microglia and pro-inflammatory cytokines predict the onset and severity of below-level neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury in rats. Exp Neurol. 2008;212:337–347. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuchars SA. How sympathetic are your spinal cord circuits? Exp Physiol. 2015;100:365–371. doi: 10.1113/EP085031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuchars SA, Lall VK. Sympathetic preganglionic neurons: properties and inputs. Compr Physiol. 2015;5:829–869. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c140020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devor M, Janig W. Activation of myelinated afferents ending in a neuroma by stimulation of the sympathetic supply in the rat. Neurosci Lett. 1981;24:43–47. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(81)90356-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devor M, Janig W, Michaelis M. Modulation of activity in dorsal root ganglion neurons by sympathetic activation in nerve-injured rats. J Neurophysiol. 1994;71:38–47. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DomBourian MG, et al. B1 and TRPV-1 receptor genes and their relationship to hyperalgesia following spinal cord injury. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:2778–2782. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000245865.97424.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong F, et al. Increased function of the TRPV1 channel in small sensory neurons after local inflammation or in vitro exposure to the pro-inflammatory cytokine GRO/KC. Neurosci Bull. 2012;28:155–164. doi: 10.1007/s12264-012-1208-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew GM, Siddall PJ, Duggan AW. Mechanical allodynia following contusion injury of the rat spinal cord is associated with loss of GABAergic inhibition in the dorsal horn. Pain. 2004;109:379–388. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond PD. Noradrenaline increases hyperalgesia to heat in skin sensitized by capsaicin. Pain. 1995;60:311–315. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond PD. Sensory-autonomic interactions in health and disease. Handb Clin Neurol. 2013;117:309–319. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53491-0.00024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond PD, Lipnicki DM. Noradrenaline provokes axon reflex hyperaemia in the skin of the human forearm. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1999;77:39–44. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1838(99)00034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Due MR, et al. Acrolein involvement in sensory and behavioral hypersensitivity following spinal cord injury in the rat. J Neurochem. 2014;128:776–786. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulin JN, et al. Licofelone modulates neuroinflammation and attenuates mechanical hypersensitivity in the chronic phase of spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2013;33:652–664. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6128-11.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin RH, et al. Interventional management of neuropathic pain: NeuPSIG recommendations. Pain. 2013;154:2249–2261. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falnikar A, et al. GLT1 overexpression reverses established neuropathic pain-related behavior and attenuates chronic dorsal horn neuron activation following cervical spinal cord injury. Glia. 2016;64:396–406. doi: 10.1002/glia.22936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnerup NB, Baastrup C. Spinal cord injury pain: mechanisms and management. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2012;16:207–216. doi: 10.1007/s11916-012-0259-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnerup NB, Jensen TS. Spinal cord injury pain—mechanisms and treatment. Eur J Neurol. 2004;11:73–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1351-5101.2003.00725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnerup NB, et al. Sensory perception in complete spinal cord injury. Acta Neurol Scand. 2004;109:194–199. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2003.00219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnerup NB, et al. Phenotypes and predictors of pain following traumatic spinal cord injury: a prospective study. J Pain. 2014;15:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming JC, et al. The cellular inflammatory response in human spinal cords after injury. Brain. 2006;129:3249–3269. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flor H, Nikolajsen L, Staehelin Jensen T. Phantom limb pain: a case of maladaptive CNS plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:873–881. doi: 10.1038/nrn1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs PN, Meyer RA, Raja SN. Heat, but not mechanical hyperalgesia, following adrenergic injections in normal human skin. Pain. 2001;90:15–23. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(00)00381-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furusawa K, et al. Incidence of symptomatic autonomic dysreflexia varies according to the bowel and bladder management techniques in patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2011;49:49–54. doi: 10.1038/sc.2010.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil DW, et al. Role of sympathetic nervous system in rat model of chronic visceral pain. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28:423–431. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein DS, Kopin IJ. Evolution of concepts of stress. Stress. 2007;10:109–120. doi: 10.1080/10253890701288935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber-Schoffnegger D, et al. Induction of thermal hyperalgesia and synaptic long-term potentiation in the spinal cord lamina I by TNF-alpha and IL-1beta is mediated by glial cells. J Neurosci. 2013;33:6540–6551. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5087-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwak YS, Hulsebosch CE. Neuronal hyperexcitability: a substrate for central neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2011;15:215–222. doi: 10.1007/s11916-011-0186-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwak YS, et al. Activation of spinal GABA receptors attenuates chronic central neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23:1111–1124. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwak YS, et al. Spatial and temporal activation of spinal glial cells: role of gliopathy in central neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury in rats. Exp Neurol. 2012;234:362–372. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habler HJ, Janig W, Koltzenburg M. Activation of unmyelinated afferents in chronically lesioned nerves by adrenaline and excitation of sympathetic efferents in the cat. Neurosci Lett. 1987;82:35–40. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(87)90167-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hains BC, Waxman SG. Activated microglia contribute to the maintenance of chronic pain after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4308–4317. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0003-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hains BC, et al. Changes in serotonin, serotonin transporter expression and serotonin denervation supersensitivity: involvement in chronic central pain after spinal hemisection in the rat. Exp Neurol. 2002;175:347–362. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hains BC, et al. Upregulation of sodium channel Nav1.3 and functional involvement in neuronal hyperexcitability associated with central neuropathic pain after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2003;23:8881–8892. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-26-08881.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hains BC, Saab CY, Waxman SG. Changes in electrophysiological properties and sodium channel Nav1.3 expression in thalamic neurons after spinal cord injury. Brain. 2005;128:2359–2371. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helkowski WM, Ditunno JFJ, Boninger M. Autonomic dysreflexia: incidence in persons with neurologically complete and incomplete tetraplegia. J Spinal Cord Med. 2003;26:244–247. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2003.11753691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou S, Rabchevsky AG. Autonomic consequences of spinal cord injury. Compr Physiol. 2014;4:1419–1453. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c130045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou S, Duale H, Rabchevsky AG. Intraspinal sprouting of unmyelinated pelvic af-ferents after complete spinal cord injury is correlated with autonomic dysreflexia induced by visceral pain. Neuroscience. 2009;159:369–379. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh YL, et al. Role of peptidergic nerve terminals in the skin: reversal of thermal sensation by calcitonin gene-related peptide in TRPV1-depleted neuropathy. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50805. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu SJ, Zhu J. Sympathetic facilitation of sustained discharges of polymodal nociceptors. Pain. 1989;38:85–90. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(89)90077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu SJ, et al. Adrenergic sensitivity of neurons with non-periodic firing activity in rat injured dorsal root ganglion. Neuroscience. 2000;101:689–698. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00414-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang LY, Neher E. Ca(2+)-dependent exocytosis in the somata of dorsal root ganglion neurons. Neuron. 1996;17:135–145. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80287-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang LY, Gu Y, Chen Y. Communication between neuronal somata and satellite glial cells in sensory ganglia. Glia. 2013;61:1571–1581. doi: 10.1002/glia.22541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob JE, et al. Autonomic dysreflexia after spinal cord transection or compression in 129Sv, C57BL, and Wallerian degeneration slow mutant mice. Exp Neurol. 2003;183:136–146. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4886(03)00161-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janig W. Sympathetic nervous system and inflammation: a conceptual view. Auton Neurosci. 2014;182:4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen TS, et al. A new definition of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2011;152:2204–2205. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Andrade JM, et al. Vascularization of the dorsal root ganglia and peripheral nerve of the mouse: implications for chemical-induced peripheral sensory neuropathies. Mol Pain. 2008;4:10. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorum E, et al. Catecholamine-induced excitation of nociceptors in sympathetically maintained pain. Pain. 2007;127:296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung H, et al. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 functions as a neuromodulator in dorsal root ganglia neurons. J Neurochem. 2008;104:254–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04969.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalous A, Osborne PB, Keast JR. Acute and chronic changes in dorsal horn innervation by primary afferents and descending supraspinal pathways after spinal cord injury. J Comp Neurol. 2007;504:238–253. doi: 10.1002/cne.21412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]