Abstract

Mechanical forces are critical but poorly understood inputs for organogenesis and wound healing. Calcium ions (Ca2+) are critical second messengers in cells for integrating environmental and mechanical cues, but the regulation of Ca2+ signaling is poorly understood in developing epithelial tissues. Here we report a chip-based regulated environment for microorgans that enables systematic investigations of the crosstalk between an organ’s mechanical stress environment and biochemical signaling under genetic and chemical perturbations. This method enabled us to define the essential conditions for generating organ-scale intercellular Ca2+ waves in Drosophila wing discs that are also observed in vivo during organ development. We discovered that mechanically induced intercellular Ca2+ waves require fly extract growth serum as a chemical stimulus. Using the chip-based regulated environment for microorgans, we demonstrate that not the initial application but instead the release of mechanical loading is sufficient, but not necessary, to initiate intercellular Ca2+ waves. The Ca2+ response depends on the prestress intercellular Ca2+ activity and not on the magnitude or duration of the mechanical stimulation applied. Mechanically induced intercellular Ca2+ waves rely on IP3R-mediated Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release and propagation through gap junctions. Thus, intercellular Ca2+ waves in developing epithelia may be a consequence of stress dissipation during organ growth.

Introduction

Organogenesis is a multiscale problem requiring the coordination of many competing developmental cues, including mechanical feedback. The fundamental question of how exogenous forces impact biochemical signaling at the organ scale is still not well characterized. The calcium ion (Ca2+) is a universal second messenger that regulates and coordinates a diverse range of intracellular processes such as proliferation and morphogenesis (1, 2). Dysregulation of Ca2+ signaling via genetic and epigenetic modifications has been implicated in human diseases including cardiomyopathies (3), cancer metastasis (4), and neurodegenerative disorders (5). Further, Ca2+ signaling has recently been correlated with actomyosin flows during tissue regeneration in the Drosophila pupal notum (6). IP3R-mediated Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release and gap junction communication has been implicated genetically as necessary for robust wing disc regeneration (7). Additionally, spontaneous intercellular Ca2+ wave dynamics depend upon still unknown chemical factors (8, 9) and are spatiotemporally patterned by morphogen signaling pathways such as Hedgehog (9). The ubiquity of Ca2+ signaling makes it difficult to identify causative mechanisms of Ca2+ regulation and function in a given biological context (2). It has been known for some time that extreme mechanical perturbations such as wounding (6, 10) and gross mechanical deformations (7) excite intercellular Ca2+ transients. However, the roles of Ca2+ in mechanical signal integration have not been systematically investigated in epithelial tissues. Analogous to Ca2+ signaling, there is compelling evidence that implicates mechanical stress as a regulator of the cell cycle, differentiation, and cell survival (11, 12). Even so, testing hypotheses on the relationships among Ca2+ signaling, genetic background, and mechanical signaling in organs is technically challenging because of the inability to apply precisely regulated mechanical and chemical perturbations to an organ culture with current practices.

Microsystems have been increasingly used to mechanically perturb individual cells and cell populations. Microsystem designs range from structures with mechanical linkages for microscale manipulation (13) to contained vessels with integrated actuators for in situ perturbation (14). Microfluidic devices are an important class of microsystem that have been used to control chemical perfusion (15) and temperature profiles (16). More recently, microfluidic devices have been used to mechanically perturb cells and confluent monolayers through deformation of microfluidic channel walls (17). In contrast to monolayers of a homogeneous cell type, organ cultures are particularly important for the study of development because they have innate morphogenetic diversity, hierarchical organization, and intact extracellular matrix. Although organlike cultures better replicate the in vivo environment (18), no device exists for combined mechanical manipulation and live imaging of intact cultured organs. Here, we present a device designed for detailed mechanical manipulation of organ cultures.

The microsystem and method presented here is designed to regulate the organ culture environment. The system permits precise environmental perturbations with enhanced image quality compared to the in vivo context. However, organs are more difficult to culture and mechanically perturb than cells, as they are generally less robust and less adherent to culture substrates. Our microfluidic device, termed the “regulated environment for microorgans chip” (REM-Chip), is designed to test organs in an ex vivo context that closely mimics the in vivo microenvironment. The key elements of the REM-Chip are: a gentle organ loading procedure; integrated fluidic channels to deliver growth media or other chemical constituents; deformable diaphragms to apply a compressive stress to an organ culture; and compatibility with small working distance objectives to enable real-time measurement of fluorescently labeled sensors.

The REM-Chip was used to probe the mechanical response of the Drosophila wing imaginal disc, which is a model organ of limb development. The wing disc has a powerful genetic toolkit and conserves many of the mechanisms of human development and disease (19) (Fig. 1 A). The wing disc develops in a naturally dynamic mechanical environment as larval organ deformation is coupled to whole body motions. Specifically, our group and others (7) have observed wing disc deformations during short-term, in vivo imaging sessions of developing larvae. In vivo intercellular Ca2+ waves (ICWs) are observed in 35% of discs (20 min of imaging, n = 72; Fig. 1 B; Movies S1 and S9) but clear correlations with specific physiological deformations during larval movement are not easy to determine. In recent in vivo studies linking Ca2+ signaling to wing regeneration (7), mechanical compression could not be precisely controlled, and Ca2+ responses were not quantified during the application of mechanical perturbations. Here we report a device and associated method to clarify that the removal and not the application of mechanical loading stimulates ICWs. In this study, we elucidate the direct causative links between mechanical stress and ICWs. We found that spontaneous and mechanically induced ICWs require fly extract (FEX), a growth serum derived from flies, to be included in the culture media. Stress relaxation is sufficient to generate ICWs under these conditions. The spatial extent of the ICW response is determined largely by the prestress Ca2+ activity of the organ, highlighting an important relationship between chemical and mechanical signaling. Surprisingly, whereas stress relaxation initiates an ICW, the ICW dynamics are independent of the magnitude and duration of the applied mechanical perturbation over the range of mechanical stresses studied. The REM-Chip is extensible to many other organ culture models and provides a powerful assay for measuring response to mechanical stimulation in organ growth, development, and homeostasis.

Figure 1.

Drosophila wing discs are a versatile system for studying intercellular Ca2+ dynamics. (A) (Left) Given here is a micrograph of a Drosophila wing disc. The wing disc is subdivided into discrete regions. The black dashed line outlines the pouch, which eventually forms the wing blade. (Right) Presented here is a cartoon showing structure and subdivision of the wing disc. (Right, inner) Given here is a top view of the wing disc showing the pouch region in gray. (Right, center) The cross section of wing disc corresponds to black dashed line shown at left and demonstrates the 3D, folded nature of the disc. (Right, outer) Shown here is a magnified view of the black box in center. The disc is composed of two epithelial sheets, a thin, squamous peripodial membrane (PM) juxtaposed to the columnar epithelium (CE) below. Black ovals represent cell nuclei in both layers. (B) Shown here is a representative example of an ICW that was observed in vivo in the wing imaginal disc. Short-duration in vivo imaging (20 min) reveals that ICWs are expressed in 35% of the in vivo experiments (n = 72), described in Wu et al. (9). The scale bar represents 100 μm.

Materials and Methods

REM-Chip design and fabrication

REM-Chip layer designs were drafted in AutoCAD and each design was converted to a photolithography mask by printing on a transparency film (Fineline Imaging, Colorado Springs, CO). Microfluidic masters, composed of a silicon wafer and SU-8 photopolymer (SU-8 3050; MicroChem, Westborough, MA), were fabricated via standard lithographic micromachining methods (20). The microfluidic channels in the REM-Chip were defined using reverse micromolding of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) on the microfluidic masters and bonded together via standard methods for two-layer microfluidic devices (21, 22). Ports were punched in the PDMS device and the entire device was cleaned using isopropyl alcohol before being bonded to a glass coverslip (21). Complete details can be found in our published protocols (21). Completed REM-Chips were stored in covered petri dishes.

Systems control and disc image acquisition

Media flow from the syringe reservoir to the REM-Chip was driven using a model No. 11 Elite programmable syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). Pressure signals to the REM-Chip were externally controlled by a custom-built pressure regulator box. The box consisted of a manual regulator to step down the house air pressure, a bank of four electropneumatic pressure regulators (ITV001-3UML; SMC, Tokyo, Japan) connected to the source pressure manifold, an analog output module, and the accompanying hardware (NI 9264; National Instruments, Austin, TX) to electronically control the reference pressure. Each analog output channel was controlled using a custom LabVIEW script (2014; National Instruments) (Text S1).

Image acquisition was performed on an Eclipse Ti confocal microscope (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY) with a Yokogawa spinning disc using an iXonEM+ cooled CCD camera (Andor Technology, South Windsor, CT). Image acquisition was controlled using the software MetaMorph v7.7.9 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

In vivo imaging

Larvae for in vivo wing disc imaging were mounted with clear tape on glass coverslips as described in Wu et al. (9) and imaged every 15 s for 20 min on a wide-field, inverted, fluorescent microscope at 20× magnification.

Sample preparation

Wing discs were cultured in chemically defined ZB-based media (23) or WM1 media (24) optimized for organ culture. Each culture chamber was prepared by filling a Plastipak 1 mL syringe (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) with 1 mL of ZB-based or WM1 media (compositions provided in Text S6), evacuating all air bubbles from the syringe, and prefilling the microfluidic network with media. Culture chambers were visually inspected under a stereomicroscope to ensure no air bubbles were present in the culture chamber or fluid lines before wing disc loading. Imaginal discs from wandering third instar larvae were then dissected in the relevant culture media. Immediately after dissection, discs were loaded into prepared REM-Chip culture chambers by pipetting the disc over the fluid inlet in a small droplet of media. The disc was positioned with a dissecting needle such that the dorsal side was facing the inlet, and the disc was drawn into the culture chamber by manually withdrawing media from the fluid outlet with a pipette (Fig. S5). After all discs were loaded into culture chambers, the REM-Chip was affixed to the microscope stage, and fluid inlet lines were connected to the media reservoir and preflooded with culture media. Inlet lines were then plugged into the REM-Chip, and media was perfused at a flow rate of 2 μL/h for the duration of all experiments.

Diaphragm and wing disc deformation study

Diaphragm deflection was measured from images of a fluorescently labeled diaphragm over a range of applied pressures. The REM-Chip was first perfused with 1.5 mM Nile red dye (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) in methanol for at least 1 h to label the PDMS channel walls. The Nile red was then evacuated from the culture chamber with deionized water. Nile red is insoluble in water. The diaphragm was imaged using confocal microscopy at applied pressures of 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 kPa. Confocal images were postprocessed in the software Fiji (https://fiji.sc/) (25) to stitch adjacent fields of view and obtain xz plane diaphragm images from the confocal z-stacks. Diaphragm deformation profiles were then measured using a custom MATLAB script (The MathWorks, Natick, MA) that filters and thresholds the xz images, detects the diaphragm edges given a user-selected region of interest, and converts pixels to distance via microscope calibrations (see Text S4.1).

Wing disc deformation under mechanical loading was studied via spinning disc confocal microscopy. Drosophila lines expressing DE-Cadherin::GFP (26), which concentrates in the subapical region of the wing disc and labels apical cell boundaries, were used to image the unbuckling and diametrical expansion of the pouch. Wing discs were excised, prepared, and loaded as per the standard protocol described above. Backpressure (0, 3, 7, 11, and 15 kPa) was statically applied to the REM-Chip diaphragm and a confocal z-stack centered on the pouch was acquired at 60× magnification in 1 μm intervals. Each z-stack of images was then processed using the software ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) (25) to generate a cross-sectional image along the AP axis of the wing disc. Particle image velocimetry (PIV) analysis was performed using a previously developed MATLAB script (27) to analyze how cells shift inside the pouch because of applied organ-scale axial compression. PIV has commonly been used in similar studies to analyze cellular movement (28). Before the PIV analysis, a rigid body registration was performed in ImageJ to remove gross disc movement due to applied compression. Additionally, a nine-pixel CLAHE contrast equalization filter and rolling ball background subtraction of 80 pixels were applied to improve detection of cell boundaries.

Comparison of the REM-Chip to dish culture

Flies expressing Lac::YFP, a green fluorescent marker for cell boundaries, were staged for 2 h in vials at 25°C. Larvae were collected for dissection at 120 h (5 days) after egg laying. Discs were dissected and loaded into the REM-Chip in WM1 media as described above or dissected and loaded into glass bottom dishes for standard culture comparison as described in Zartman et al. (24). Discs were imaged at 40× magnification every 30 min for a minimum of 12 h. A 250 × 250 pixel region, representing one-quarter of the total frame size, was cropped from each video frame, centered on the wing disc pouch. The cropped regions were saved with descriptive filenames. The filenames were then randomized, and a key was automatically created using a freely available batch script (Supporting Material) to create a blinded set of images. The numbers of mitotic cells per area were tabulated by counting the number of rounded cells with increased apical area, a characteristic of mitosis. The data were compared for statistical difference using a repeated measures ANOVA test.

ICW mechanism study

A tester line, used for all experiments, was created by recombining nub-GAL4 with UAS-GCaMP6f on the second chromosome (w1118; nub-GAL4, UAS-GCaMP6f/CyO). This line was crossed with UAS-Gene-of-interestRNAi lines to perturb essential components of the IP3 signaling cascade (full details provided in Text S5). Discs from wandering third instar larvae from each cross were dissected and loaded into the REM-Chip as previously described. These discs were imaged at 10× magnification on an Eclipse Ti confocal microscope (Nikon Instruments) for a total of 30 min, imaging every 10 s (all supplemental movies are rendered at 15 frames/s). While being imaged, the discs were subjected to the following schedule of applied pressures: 300 s at 0 kPa, 30 s at 15 kPa, 300 s at 0 kPa, 30 s at 15 kPa, 300 s at 0 kPa, 30 s at 15 kPa, and 300 s at 0 kPa. Pressure fluctuations had a rise time of 1 s. Videos were scored for the presence or absence of ICW formation after diaphragm release for each RNAi cross tested. The control group consisted of uncrossed discs from the tester line, subjected to the same schedule of applied pressures and imaging regimens. To ensure that the result observed was not due to off-target effects, a combination of multiple RNAi lines or pharmacological inhibitors were used for each perturbation. Drugs tested were 200 μM 2-aminoethyl diphenylborinate for inhibition of IP3R and 30 μM carbenoxolone for inhibition of Inx2 (10). For pharmacological tests, two wing discs from the same larva were dissected from the tester line. One disc was incubated for 20 min in media containing the pharmacological inhibitor for the target gene and the other in media containing an equivalent volume of the carrier solvent (ethanol and DI water, respectively). Discs were then loaded into the REM-Chip and imaged as described above.

REM-chip compression study

Wandering third instar wing discs from the tester line were dissected and loaded into the REM-Chip as previously described. Each experiment consisted of a set of three, unique, third instar wandering wing discs tested in parallel. Each wing disc was subjected to either 10, 15, or 20-kPa diaphragm backpressure for a randomized set of three compression durations consisting of 30, 300, and 600 s each. Each compression period was preceded and followed by a 600 s quiescent period (0 kPa) to observe the Ca2+ dynamics. Discs were imaged as described above, except the total imaging period was extended to 60 min to accommodate the increased backpressure duration. Videos were randomly renamed as described above for blind analysis. The time to initiation, velocity, burst time, burst area fraction, and peak mean pouch intensity of each mechanically induced ICW were quantified based on changes in pixel intensity using a combination of the softwares Fiji and MATLAB. Complete details of the analysis are provided in Fig. S8 and Text S7.

Fly lines and reagents

Ca2+ signaling was visualized using the GAL4-UAS system (29). The Ca2+ signaling sensor UAS-GCaMP6f (30) (Bloomington stock #42747) was recombined with the nubbin-GAL4 driver (Bloomington stock #25754) to provide a readout of Ca2+ activity in the wing disc pouch (nub-GAL4>UAS-GCaMP6f), which we term the “GCaMP6f tester line”. For genetic perturbation experiments, the GCaMP6f tester line was crossed to TRiP lines for the targeted gene (all genotypes listed in Text S5). All flies were raised at 25°C, 70% relative humidity on cornmeal agar (31). All reagents are listed in Text S5.

Image analysis routines

Supplemental movies to accompany figures are described in Text S8. All scripts used in the analysis of image data are included in Supporting Material and described in Text S9.

Results

REM-Chip system design

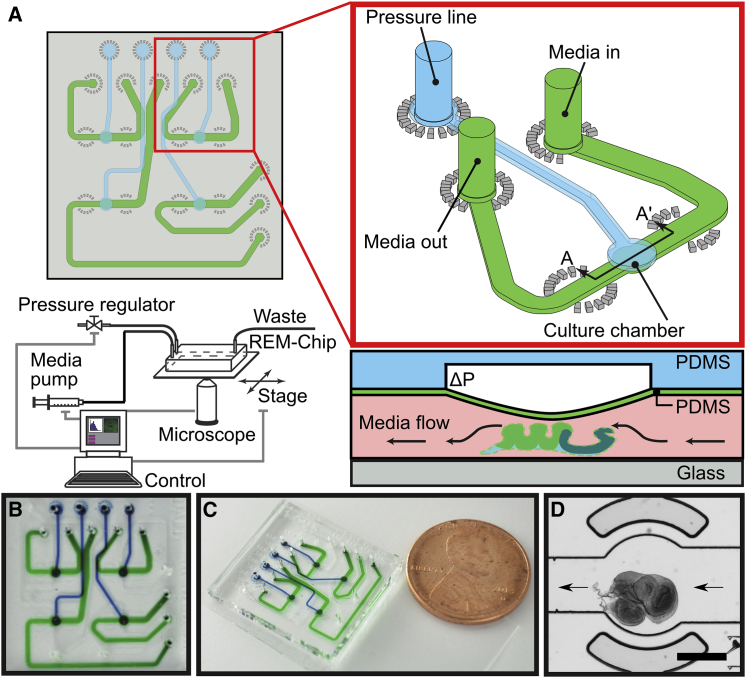

The REM-Chip is a two-layer microfluidic device that modulates the local chemical and mechanical microenvironment of a developing wing disc (Fig. 2). Both layers are made from the flexible, optically transparent, polymer PDMS and are bonded to a glass coverslip (Fig. 2 A). Organ culture media and other chemical constituents flow in the bottom layer, and a pneumatically controlled deformable diaphragm in the top layer applies compression perpendicular to the imaging plane. The REM-Chip is integrated into a system composed of: a syringe pump for driving media flow; an array of pressure transducers to control diaphragm deflection; and a spinning-disc confocal microscope with coordinated stage translation and imaging routines (Fig. 2 A; Figs. S1–S3 and Text S1). Earlier iterations of the REM-Chip design are shown in Fig. S4 and described in Text S2.

Figure 2.

REM-Chip. (A) REM-Chip schematic is shown at top left with detail of a single chamber unit (red box). An individual culture chamber and the accompanying fluid (green) and pressure (blue) lines are integrated within a larger chip of four individually addressable culture chamber wells, for parallel experimentation, and part of a computer controlled network of external hardware (lower left). Shown here is a diagram showing a cross section of culture and pressure chambers through line (A–A′) showing operation of the diaphragm mechanism for compressing wing discs is shown below the red inset box. An applied pressure signal to an empty chamber in the PDMS layer above the wing disc in culture (white box in blue layer) deforms a thin membrane (green) that is the ceiling of the media channel. Fluid space inside the channel is shown in pink. (B and C) Shown here are photos of the device with individually addressable fluid (green) and pressure (blue) channels for each culture chamber. A US penny is shown for scale. (D) Shown here is a third instar wing disc loaded into a culture chamber of a REM-Chip. Arrows indicate direction of media flow. The scale bar represents 400 μm.

The wing disc loading protocol is optimized to reduce wing disc stress. The inlet channel of the REM-Chip is large enough (nominally 600 × 100 μm) for a wing disc to be loaded by flowing the disc through the channel. The channel is first flushed with organ culture media, and a wing disc is pipetted into the inlet. Next, the disc is positioned in the culture chamber by withdrawing organ culture media through the outlet channel with a pipette (Fig. S5 and Text S3). Once loaded, culture media is flowed at 2 μL/h via a syringe pump to deliver media and chemicals; this low flowrate does not perturb the position of the wing disc. The area of the culture chamber is larger than an average wing disc to allow for variation in wing disc size and diametrical expansion during mechanical compression. The culture chamber size for wing discs is nominally 800 μm in diameter by 100 μm in height, but can be adjusted to accommodate other model systems.

Validation of the REM-Chip

Mechanical loading is applied to the wing disc by the REM-chip’s diaphragm, which is controlled via the pressure line. The deflection of the center of the circular diagram increases monotonically with applied pressure, as measured by confocal microscopy of diaphragms labeled by the fluorescent dye Nile red (Fig. 3, A and B; Movie S2). A pressure in excess of 20 kPa results in contact between the diaphragm and the bottom of the chamber, setting the upper limit for mechanical loading experiments. The deflection-pressure relationship is in close agreement with a mechanics model of the deflection of a circular membrane under a uniform load (32) and is in agreement with the behavior of similar PDMS structures (33) (Fig. S6 and Text S4.2). Deflection as a function of pressure for an individual diaphragm is repeatable to within ±2 μm (standard deviation, SD), suggesting that variability in the system is negligible (Fig. 3 B; Fig. S6 A). Further, the elastic modulus of PDMS exceeds that of the wing disc by an order of magnitude, 106 versus 105 Pa, respectively (34, 35). Therefore, small variations in the elastic modulus of the device membrane from run to run are expected to have negligible impact on the disc deflection and response. Imaging of a wing disc compressed at increasing applied pressures demonstrates that the natural folds at the apical surface near the pouch flatten and expand when the disc is pressed against the glass coverslip by the diaphragm. This behavior is shown by a cross section through the center of a representative wing disc pouch shown in Fig. 3 C. Additionally, PIV analysis was performed to analyze how the cell vertices move as a result of an applied compression (28). PIV analysis of cell movements as marked with ECadherin::GFP demonstrate that for late third instar wing discs, cells are pushed preferentially from the periphery of the disc toward the center (27). This observation supports the idea that cells at the center of the tissue are stiffer, consistent with the observation of actomyosin accumulation along the D-V axis during development (Fig. 3, E–G) (36, 37, 38).

Figure 3.

Validation of mechanical perturbations and wing disc culture in the REM-Chip. (A) Given here is a diaphragm stained with Nile red dye and imaged on a confocal microscope at indicated pressures. The scale bar represents 400 μm. (B) Given here are measured diaphragm deflection profiles at the pressures indicated. Solid, dashed, and dotted lines indicate the first, second, and third pressure applications, respectively. Note the consistency of membrane position during each subsequent pressurization. (C) Given here is a cross section through the A-P axis of a wing disc pouch expressing a fluorescent marker for E-Cadherin (DE-Cadherin::GFP) and showing deformation of the disc at the given applied pressures. The scale bar represents 100 μm. (D) Shown here is a proliferation curve. Given are cell divisions per 7656 μm2 area (250 × 250 pixels) per time point for wing discs cultured in the REM-Chip and in standard dish cultures. Sample size n = 5 for dish and n = 3 for REM-Chip; error bars are SD here and elsewhere. (E–G) Given here is a PIV analysis of cell movements in the center of a wing disc pouch as a result of deformation performed using the MATLAB code developed in Thielicke and Stamhuis (27). (E) Given here is the maximum Z-projection (60× magnification) of the same pouch shown in (C). The green box outlines the area of interest for the PIV analysis. The red dashed line marks the D-V boundary of the wing disc. (F). Shown here is the area of interest outlined in (E). The scale bar represents 50 μm. (G) The velocity vector field is shown for increasing applied backpressure between 0 and 15 kPa. Rigid body registration removes nondeformation disc drift as a result of applied backpressure. Cell flow is preferential from the edge of the disc toward the disc center, consistent with the axial buckling shown in (C).

Cell division is a sensitive indicator of wing disc health and metabolic activity (24). Wing discs cultured in the REM-Chip using the optimized culture media formula WM1 (24) demonstrate no statistical difference in the number of mitotic cells when compared to discs cultured in a glass-bottom dish in the same media (repeated measures ANOVA, p = 0.95) (Fig. 3 D). These results also agree with reported organ mitotic indices up to ∼12 h on glass-bottomed wells (24, 39, 40). Thus, the REM-Chip can be used to study cellular processes over the course of multiple hours because culture in the REM-Chip does impact proliferative activity relative to established methods.

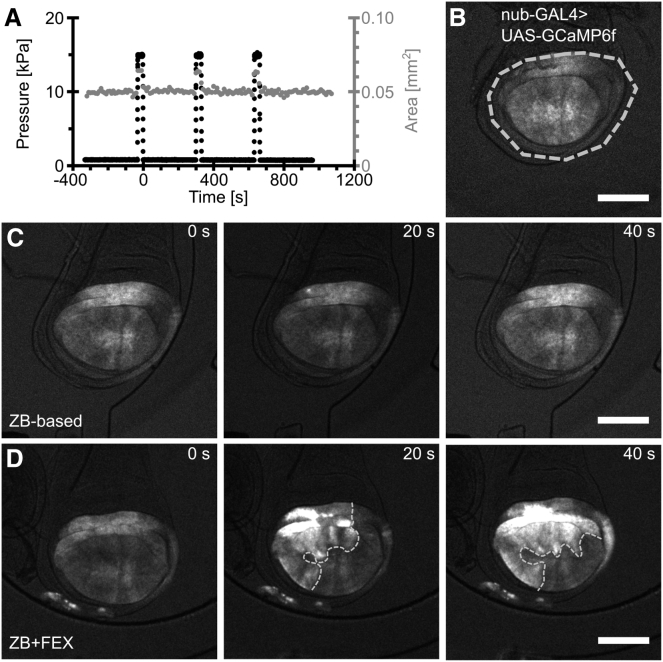

ICWs require a chemical signal

ICWs have been recently reported in wing discs both in vivo and ex vivo (7, 8, 9). We found that whole FEX, a protein-rich serum often added to culture media to support growth and proliferation of Drosophila tissues, is necessary for the formation of ICWs ex vivo (Fig. 4 and (8, 9, 41)). ICWs were first observed in ex vivo cultured wing discs cultured in WM1 media, which contains FEX (7). Removal of FEX serum from WM1 media results in a complete loss of ICW activity. Conversely, addition of FEX serum to ZB media, a chemically defined culture medium, results in the formation of ICWs (Movie S4) that are otherwise not present (Movie S3) (23). ZB media was engineered to support long-term proliferation and passaging of the wing-disc-derived Cl.8 cell line (23). These results demonstrate that specific chemical stimulation by FEX is specifically required for the generation of both spontaneous and mechanically stimulated ICWs.

Figure 4.

Release of applied mechanical loading results in an ICW. (A) Shown here is an experimental plot of applied pressure with time and the change in pouch area with time for a cultured wing disc. Pulses in the pouch area (gray line) correspond to pulses in the backpressure applied to the diaphragm (black line) and demonstrate mechanical perturbation of the wing disc. Time t = 0 corresponds to the first frame after release of the diaphragm. (B) Image shows the disc in the culture chamber before compression. The nub-GAL4 drives expression of the genetically encoded Ca2+ sensor GCaMP6f to visualize intercellular Ca2+ signaling throughout imaging. The white dashed line indicates the maximum extent of pouch expansion during diaphragm deflection. Without the addition of FEX to the culture media, no waves are observed to form either with or without compression. (C and D) Given here is a montage of two discs cultured in ZB-based media without (C) or with (D) 15% FEX (n = 3). Time 0 for each montage indicates the frame immediately after release of the diaphragm. In the absence of FEX, intercellular transients are not observed after the release of mechanical loading (C). In the presence of FEX, stress relaxation after release of mechanical loading initiates an ICW. The wave front is annotated by the white dashed line (D). The scale bars represents 100 μm.

Release of mechanical loading initiates ICWs

Mechanical perturbations have recently been implicated as a potential cause of the large ICWs in imaginal discs (7). However, experimental methods to allow wing disc observation during active compression, or control the level and duration of the applied compressive stress, were previously unavailable. Here, we have created a device that enables direct, quantitative tests of the hypothesis that mechanical stimulation modulates ICWs. A wing disc under a compressive stress applied by the diaphragm diametrically expands with a positive correlation with applied pressure (Fig. 4, A and B). The release of this compressive stress initiates an ICW (Fig. 4, C and D). ICWs are observed in 81% of compression events (n = 51/63) on release of mechanical loading in ZB media with 15% FEX. Mechanical loading inhibits the formation of spontaneous ICWs. ICWs were never observed to form during mechanical loading for up to a 10-min period (n = 63 compressions). We observe 52% of discs (n = 11/21) exhibit spontaneous ICW formation without mechanical induction within a 10-min period. ICWs already underway were not stopped by mechanical loading (Movie S9). Release of mechanical loading, exerted by a diaphragm backpressure of 15 kPa initiates an ICW 20 ± 30 s (SD) after release (min = 0 s, max = 180 s) (Fig. 4 C). Tissue-level stress relaxation in the absence of FEX is not sufficient to initiate an ICW, indicating that mechanical initiation of ICW activity is dependent on the presence of FEX in the media (Fig. 4 D). The outer folded region of the nub>GCaMP6f expressing domain of the wing disc is oriented such that the apical-basal direction of cells is in the plane of axial compression, resulting in lateral stretching in this region of the disc when the diaphragm is deflected. This portion of the wing disc shows persistent, active ICWs (Movie S4), suggesting that stretching promotes ongoing Ca2+ activity. This is opposed to the center of the disc pouch where cells are compressed and ICW activity is inhibited under mechanical loading (Fig. 3; Movie S4).

Mechanically induced ICWs depend principally on the organ’s physiological status

To investigate important factors governing the extent of ICW activity, we performed a series of mechanical loading experiments varying duration and magnitude of loading over multiple biological experiments (n = 21, three experiments). Each wing disc was loaded into the REM-Chip, held at 0-kPa backpressure for the first 10 min, and then subjected to 10-, 15-, or 20-kPa diaphragm backpressures. A series of three loading/no-loading cycles were performed on each disc. The order of duration of loading was randomized: 30, 300, and 600 s. The wing disc response to mechanical perturbations for this data set could be binned into two differing populations. Discs were visually scored based on their prestress Ca2+ activity while blinded to all poststress response activity. Discs that showed qualitatively consistent spontaneous ICW activity in the first 10 min before loading consistently responded to release of the mechanical loading (n = 34/36 perturbations) (Fig. 5, A–C). Discs that are naturally quiescent, exhibiting low-medium spontaneous ICW activity (small bursts) in the first 10 min of culture, responded to mechanical loading much less frequently (n = 17/27) with low- to medium ICW activity (Fig. 5, A–C). In many cases, Ca2+ burst area due to release of mechanical loading covered the same spatial extent as the spontaneous, preloading ICW events. More localized ICWs frequently initiated near the edge of the pouch with an inward direction toward the geometric center of the tissue (Movie S4). Significant population-level effects were observed in the peak mean pouch intensity after release (p < 0.03), ICW burst time (p < 0.001), and fraction of wing disc pouch occupied by the ICW (p < 0.001). Two-tailed Student’s t-test with Bonferroni correction was used to obtain p values.

Figure 5.

Magnitude and extent of ICWs depend on the physiological status of the tissue. (A) Given here is the plot of the peak mean pouch intensity after release of organ-scale mechanical loading normalized to the basal Ca2+ level. Active discs produce much larger ICWs (C) that tend to last longer (B), resulting in a significantly increased peak mean pouch intensity (p < 0.03). (B) Given here is the plot of ICW burst time calculated as the last frame that an ICW is observed after compression minus the first. Active discs produce ICWs that last longer, regardless of applied backpressure or hold times applied (p < 0.001). (C) Given here is a plot of the fraction of total pouch area occupied by the mechanically induced ICW. Active discs produce much larger ICWs than quiescent discs regardless of the applied pressure or hold time (p < 0.001). (D) These results and observations lead to the working model that mechanical stimulation amplifies and forces the existing FEX-induced ICW response. The p values are from a Student’s t-test with Bonferroni correction.

In comparison to the subpopulation effect, we saw comparatively minor effects of applied backpressure, pouch deflection, or backpressure hold time on the burst area, burst time, normalized mean peak intensity in the pouch, velocity, or delay of the ICW response over the ranges tested (Fig. S9). Mechanically stimulated ICW velocity was found to be 1.0 ± 0.5 μm/s, and the time to initiation was found to be 20 ± 30 s (SD; min = 0 s, max = 180 s). Taken together, stimulation of ICWs results after release of applied mechanical loading on the tissue, but the extent of the ICW depends on the prestress ICW activity stimulated by the presence of FEX and not on the magnitude or duration of the applied stimulus (Fig. 5 D). To rule out the possibility that variations in the level of GCaMP were responsible for generating the observed subpopulation effect, the average basal fluorescence of the pouch was obtained using the software ImageJ for the 10 min before the first stress event. This basal fluorescence value was plotted against the normalized mean pouch intensity, burst area fraction, and burst time of the release-induced wave. No correlations were observed (Fig. S10), indicating that basal GCaMP fluorescence is not indicative of a disc’s ability to respond to stress dissipation.

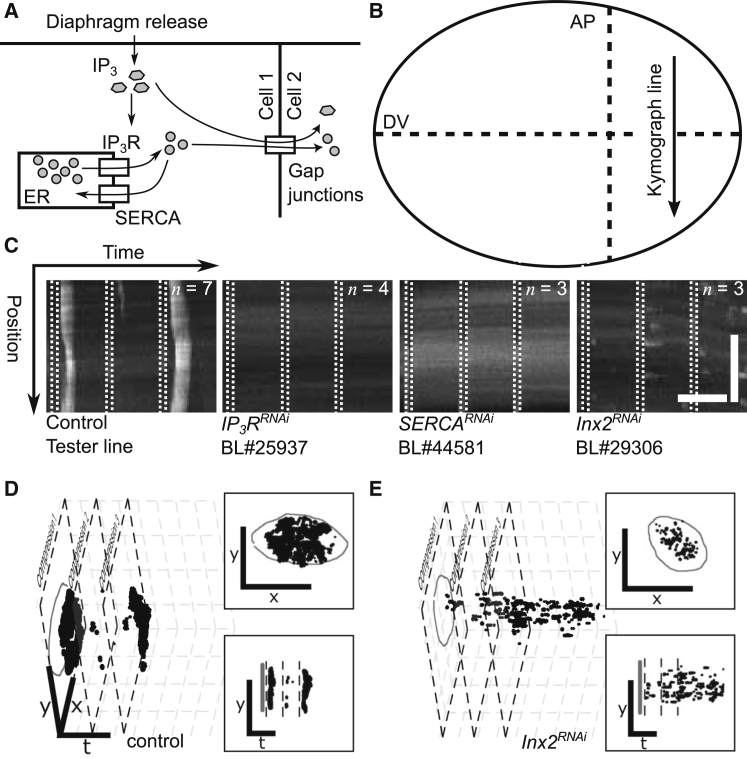

Mechanically stimulated ICWs result from IP3-mediated release from intracellular stores and depend on gap junction activity

We performed a targeted genetic screening approach to define the mechanism of ICW formation occurring due to mechanical stimulation compared to wound-induced and spontaneous ICWs. IP3 signaling is highly conserved and present in both Drosophila and vertebrate models as an important mediator of Ca2+ release. The IP3 signaling cascade releases Ca2+ from internal stores in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) by binding with its receptor, IP3R. Previously, we have delineated that laser-ablation induced intercellular Ca2+ flashes in wing discs through IP3-mediated Ca2+ release and subsequent propagation through gap junctions (GJs) (10). This mechanism is well established for intercellular transients as a result of wounding (10, 42) and is also responsible for intracellular waves observed during Drosophila oogenesis (43). To test whether mechanical induction of ICWs also rely on this conserved IP3-mediated mechanism, RNAi was used to knock down key components of this cascade (Fig. 6 A). We found that inhibition of GJs through Inx2RNAi, inhibition of the IP3 receptor (IP3RRNAi), and inhibition of the ER pump SERCA (SERCARNAi) all completely abolish the mechanically induced ICWs (Fig. 6, B and C; Movie S6. IP3RRNAi, Movie S7. SERCARNAi, Movie S8. Inx2RNAi, Movie S9. ICW Activity). Taken together, these results suggest that IP3-mediated release from intracellular stores and GJ communication between neighboring cells are necessary for the propagation of mechanically induced ICWs. Knockdown of SERCA shows a characteristic increase in basal Ca2+ level consistent with impairment of the ability to uptake cytoplasmic Ca2+ into the ER (Fig. 6 C). This suggests that once the concentration of Ca2+ in the ER stores drop below a critical threshold, cells are unable to respond through this mechanism. This is in agreement with recently published work on wound-induced ICWs in Drosophila wing discs (7, 10). Interestingly, although GJ inhibited discs (Inx2RNAi) do not develop ICWs, increased flashing of individual cells is observed on stress relaxation (Fig. 6, D and E). As a control, inhibition of ryanodine receptor by RNAi (RyRRNAi) was tested and shown to permit formation of the release-induced ICW (Fig. S11). This provides evidence that the observed ICW suppression is not due to GAL4 dilution. At least two RNAi lines or an RNAi line and pharmacological inhibition were tested to ensure that the response was not due to off-target effects. Pharmacological perturbations for Inx2 (30 μM carbenoxolone) and IP3R (200 μM 2-aminoethyl diphenylborinate) were tested and found to give equivalent responses to the strongest identified RNAi lines. Results from the additional RNAi and pharmacological tests are detailed in Fig. S11. Cumulatively, these results suggest that stress relaxation increased Ca2+ spiking in individual cells, which was likely mediated by IP3. GJ activity enables transmission of IP3 and Ca2+ throughout the tissue. Additional details on all RNAi lines and their validation can be found in (Fig. S7 and Text S5). Interestingly, knockdown of these genes also resulted in a loss of all prestress Ca2+ and has been shown to abolish spontaneous wave activity in the wing disc (9). These results are consistent with the mechanism found to be responsible for wound-induced intercellular Ca2+ transients in wing disc (10) and spontaneous intercellular Ca2+ in the wing disc in studies performed in our lab and by Balaji et al. (8), Wu et al. (9), and Narciso et al. (41).

Figure 6.

Mechanism of stress relaxation-induced ICWs. (A) Illustration of key Ca2+ signaling components involved in mechanically induced ICWs in the wing imaginal disc. (B) Given here is a schematic of the sampling line for the kymographs shown the wing disc in (C). (C) Shown here is the intensity of GCaMP6f signal as a function of time along the sampling line for representative samples from the indicated populations. Sample size for each population is indicated. White bands represent periods of mechanical loading. The control represents the tester line (nub-GAL4>UAS-GCaMP6f) and the gene-of-interest lines are each crossed to the tester line and are detailed in Text S5. Taken together, this data strongly suggests that the mechanically stimulated ICW response is the result of IP3-mediated release from intracellular stores in the ER. The temporal scale bar (horizontal) represents 300 s; the spatial scale bar (vertical) represents 50 μm. (D and E) 3D plots of xy fluorescence isosurfaces with respect to time for the control case (D) and Inx2RNAi (E). The pouch region is outlined in gray. In (E), although an ICW does not form, there is an increase in discrete cell flashing indicating that the disc can still sense mechanical perturbation. Insets to (D and E) show xy (top) and yt (bottom) views of the 3D plots. The temporal scale bars (t direction) represent 500 s and spatial scale bars (x and y direction) represent 200 μm.

Discussion

The REM-Chip enables new chemical and mechanical assays for organ cultures

Mounting evidence suggests that both chemical and mechanical cues impact organ development (44, 45). The REM-Chip is a powerful tool for providing controlled mechanical and chemical microenvironments compatible with long-term organ cultures. Recent observations have linked mechanical stress to ICWs in wing discs (7); however, these experiments relied on manual methods to apply mechanical perturbations. These previous methods allow little control over magnitude or extent of the applied perturbation. Our REM-Chip design allows reproducible and controlled mechanical loading of wing discs. Importantly, the ICW response to mechanical perturbation is found to be dependent specifically on the release, rather than the application, of mechanical loading—a distinction lacking in previous observations of mechanically induced ICWs in both cultured cells and tissues. This observation is significant for two reasons. First, developing wing discs and other organs are constantly deformed via organismal and morphogenetic movements. Second, this observation posits interesting questions for further investigation. For instance, what are the downstream effects of mechanically induced ICWs on transcription, translation, and mechanical properties of tissues? Although other approaches have enabled mechanical perturbation of Drosophila systems (7, 13, 46, 47), the high fidelity mechanical control enabled by the REM-Chip expands the scope of available mechanical assays for organ culture. More generally, the REM-Chip system provides an attractive characterization tool to study the mechanotransduction properties of heterologous channels and mechanoreceptors that can easily be expressed using current Drosophila genetic tools. In addition, the REM-Chip will enable future efforts that seek to develop and test novel pressure-based synthetic biology input/output modules that integrate both chemical and mechanical inputs. Finally, the REM-Chip represents an extensible platform that can be modified to test the impact of other exogenous stimuli, such as electrical gradients, on organ growth and development.

Interplay between chemical and mechanical stimulation of ICWs

The REM-Chip has revealed that mechanical stimulation, specifically stress relaxation after release of mechanical loading, is a potent inducer of ICWs. In this initial study, the precise correlations between 3D cell deformations and initiation of ICWs was not attempted. Axial compression applied to a cell results in perpendicular expansion leading to tensile stresses due to the Poisson effect. It is possible that relaxation from tensile stresses causes stretch-activated calcium channels to open and initiate calcium-induced calcium release. Transmission through gap junction then leads to expansion of the ICW. These questions warrant future investigations. We note that we have not observed the generation of ICWs immediately on the DV axis. Induction of ICWs occur after mechanical perturbations only in the presence of FEX, indicating that both chemical and mechanical factors play a role in this response. Both in vivo observations and ex vivo experiments indicate heterogeneity in Ca2+ responses at the organ scale. This could indicate that there are distinct organ states that determine calcium signaling response in analogy to known heterogeneity in single cell studies of Ca2+ signaling (48). This leads to two possibilities requiring future investigations: 1) either FEX is a permissive growth medium that enables intrinsic Ca2+ oscillations to occur in the wing disc with coordination of response mediated by extensive GJ communication or 2) there is an instructive component in FEX, albeit currently unknown, that stimulates calcium-induced calcium release to generates ICWs. Ongoing work in our lab currently favors the latter explanation. Results from Balaji et al. (8) showing the suppression of spontaneous ICW activity by the actomyosin inhibitor blebbistatin offers further evidence that these waves are linked to mechanical transduction. Actomyosin and integrin/cadherin interactions are critical to cellular mechanosensation (49). This suggests that cells may sense these mechanical changes through an actomyosin-based mechanism and that the ICW in developing epithelia may be a consequence of stress dissipation during organ growth. RNAi against key components of the IP3 signaling cascade revealed that ICWs result from IP3-mediated release and travel through GJ-mediated communication. Although Inx2RNAi prevents the formation of ICWs, increased flashing of individual cells is observed after release of the mechanical stimulation, suggesting that cells are still able to sense mechanical perturbations. This provokes the question of whether compressive stress is mainly inhibiting production of IP3 rather than closing GJs. Although mechanical stimulation is sufficient to initiate ICWs, it is not the primary driver of ICWs, as they can be observed spontaneously in the absence of any observable mechanical perturbation, consistent with in vivo observations. This suggests a chemical signal contained in the FEX serum is the primary source of spontaneous ICWs in wing discs. The exact nature of such chemical factors and how they are developmentally regulated are subjects for future research.

Conclusions

We developed a microfluidic ex vivo culture platform for mechanical perturbation of Drosophila wing imaginal discs and have shown that the release, but not the application, of mechanical loading at the organ-scale is sufficient to initiate an ICW. Wing disc proliferation supported by culture in the REM-Chip is equivalent to established ex vivo methods. Furthermore, chemical and mechanical perturbations are completely automated, paving a clear path for long-term investigations of organ growth and homeostasis. Such investigations have been previously carried out in cell cultures (50, 51) but not in hierarchically organized organ cultures. Other potential long-term studies include the examination of how mechanical and chemical perturbations effect morphogenetic patterning in tissues. Lastly, although this specific REM-Chip detailed here is tailored for the Drosophila wing disc, simple modifications to channel and chamber dimensions will enable identical assays to be applied to other Drosophila organs in addition to a broad range of microorgan explants from developmental models such as Xenopus, zebrafish, and human organoid cultures.

Author Contributions

D.J.H. and J.J.Z. conceived the project. C.E.N. validated and performed organ culture studies. N.M.C. performed diaphragm deflection studies. T.J.S. participated in REM-Chip design including the pressure and vacuum regulator system, and contributed to Fig. 2. D.J.H. initially designed the REM-Chip and integrated system. C.E.N., N.M.C., D.J.H., and J.J.Z. designed the experiments, analyzed the results, and wrote the paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Notre Dame Integrated Imaging Facility and the Notre Dame Nanofabrication Facility for the use of their imaging and fabrication facilities; Melinda Lake and Maxwell Kennard, respectively, for their assistance with REM-Chip fabrication and pressure and vacuum regulator system design; and Megan Levis for technical assistance. The authors thank S. Shvartsman, J. Boerckel, S. Restrepo, members of the Zartman lab, and the anonymous reviewers for feedback on the manuscript.

The work in this manuscript was supported in part by National Science Foundation (NSF) Award CBET-1403887 and the Notre Dame Advanced Diagnostics & Therapeutics Berry Fellowship.

Editor: Stanislav Shvartsman.

Footnotes

David J. Hoelzle’s present address is Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, the Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio.

Supporting Materials and Methods, eleven figures, three tables, nine movies, and one data file are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(17)30626-4.

Contributor Information

David J. Hoelzle, Email: hoelzle.1@osu.edu.

Jeremiah J. Zartman, Email: jzartman@nd.edu.

Supporting Material

A Drosophila wing disc imaged in vivo shows formation of an ICW (see Fig. 1 b).

Diaphragm deflections at increasingly applied backpressures (see Fig. 1 c).

ICWs are not observed if FEX is not included in the culture media (see Fig. 4 c).

ICWs form on release of mechanical loading when 15% FEX serum is added to the chemically defined ZB culture medium (see Fig. 4 d).

Release of applied mechanical loading stimulated intercellular Ca2+ waves in the nub-GAL4, UAS-GCaMP6f disc. (see Fig. 5 c).

Knockdown of IP3R abolishes the mechanically induced Ca2+ wave (cross with BL#25937) (see Fig. 5 c).

Knockdown of SERCA abolishes the mechanically induced Ca2+ wave (cross with BL#44581) (see Fig. 5 c).

Knockdown of Inx2 abolishes the release-induced Ca2+ wave (cross with BL#29306) (see Fig. 5 c).

CW activity immediately before application of the mechanical perturbation.

References

- 1.Yuen M.Y.F., Webb S.E., Miller A.L. Characterization of Ca2+ signaling in the external yolk syncytial layer during the late blastula and early gastrula periods of zebrafish development. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1833:1641–1656. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berridge M.J., Lipp P., Bootman M.D. The versatility and universality of calcium signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000;1:11–21. doi: 10.1038/35036035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lebeche D., Davidoff A.J., Hajjar R.J. Interplay between impaired calcium regulation and insulin signaling abnormalities in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Nat. Clin. Pract. Cardiovasc. Med. 2008;5:715–724. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prevarskaya N., Skryma R., Shuba Y. Calcium in tumour metastasis: new roles for known actors. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2011;11:609–618. doi: 10.1038/nrc3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berridge M.J. Dysregulation of neural calcium signaling in Alzheimer disease, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Prion. 2013;7:2–13. doi: 10.4161/pri.21767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antunes M., Pereira T., Jacinto A. Coordinated waves of actomyosin flow and apical cell constriction immediately after wounding. J. Cell Biol. 2013;202:365–379. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Restrepo S., Basler K. Drosophila wing imaginal discs respond to mechanical injury via slow InsP3R-mediated intercellular calcium waves. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12450. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balaji R., Bielmeier C., Classen A.-K. Calcium spikes, waves and oscillations in a large, patterned epithelial tissue. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:42786. doi: 10.1038/srep42786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu Q., Brodskiy P., Zartman J.J. Morphogen signalling patterns calcium waves in the Drosophila wing disc. bioRxiv. 2017 http://biorxiv.org/content/early/2017/02/01/104745 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Narciso C., Wu Q., Zartman J. Patterning of wound-induced intercellular Ca2+ flashes in a developing epithelium. Phys. Biol. 2015;12:056005. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/12/5/056005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Renò F., Sabbatini M., Cannas M. In vitro mechanical compression induces apoptosis and regulates cytokines release in hypertrophic scars. Wound Repair Regen. 2003;11:331–336. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2003.11504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hariharan I.K. Organ size control: lessons from Drosophila. Dev. Cell. 2015;34:255–265. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schluck T., Nienhaus U., Aegerter C.M. Mechanical control of organ size in the development of the Drosophila wing disc. PLoS One. 2013;8:e76171. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang S., Saif T. Micromachined force sensors for the study of cell mechanics. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2005;76:044301. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang X., Dhumpa R., Roper M.G. Maintaining stimulant waveforms in large-volume microfluidic cell chambers. Microfluid. Nanofluidics. 2013;15:65–71. doi: 10.1007/s10404-012-1129-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lucchetta E.M., Lee J.H., Ismagilov R.F. Dynamics of Drosophila embryonic patterning network perturbed in space and time using microfluidics. Nature. 2005;434:1134–1138. doi: 10.1038/nature03509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bleuel J., Zaucke F., Niehoff A. Effects of cyclic tensile strain on chondrocyte metabolism: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119816. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fatehullah A., Tan S.H., Barker N. Organoids as an in vitro model of human development and disease. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016;18:246–254. doi: 10.1038/ncb3312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilbert L.I. Drosophila is an inclusive model for human diseases, growth and development. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2008;293:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xia Y., Whitesides G.M. Soft lithography. Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 1998;28:153–184. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lake M., Narciso C., Hoelzle D. Microfluidic device design, fabrication, and testing protocols. Protoc. Exch. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Unger M.A., Chou H.-P., Quake S.R. Monolithic microfabricated valves and pumps by multilayer soft lithography. Science. 2000;288:113–116. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5463.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burnette M., Brito-Robinson T., Zartman J. An inverse small molecule screen to design a chemically defined medium supporting long-term growth of Drosophila cell lines. Mol. Biosyst. 2014;10:2713–2723. doi: 10.1039/c4mb00155a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zartman J., Restrepo S., Basler K. A high-throughput template for optimizing Drosophila organ culture with response-surface methods. Development. 2013;140:667–674. doi: 10.1242/dev.088872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Cardona A. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang J., Zhou W., Hong Y. Directed, efficient, and versatile modifications of the Drosophila genome by genomic engineering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:8284–8289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900641106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thielicke W., Stamhuis E. PIVlab—towards user-friendly, affordable and accurate digital particle image velocimetry in MATLAB. J. Open Res. Softw. 2014;2:e30. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ganguly S., Williams L.S., Goldstein R.E. Cytoplasmic streaming in Drosophila oocytes varies with kinesin activity and correlates with the microtubule cytoskeleton architecture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;109:38. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203575109. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22949706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duffy J.B. GAL4 system in Drosophila: a fly geneticist’s Swiss Army knife. Genesis. 2002;34:1–15. doi: 10.1002/gene.10150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tian L., Hires S.A., Looger L.L. Imaging neural activity in worms, flies and mice with improved GCaMP calcium indicators. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:875–881. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ashburner M. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1989. Drosophila: A Laboratory Handbook. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schomburg W.K. Introduction to Microsystem Design. Springer; Berlin, Germany: 2011. Membranes; pp. 29–52. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chiou C.-H., Yeh T.-Y., Lin J.-L. Deformation analysis of a pneumatically activated Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) membrane and potential micro-pump applications. Micromachines (Basel) 2015;6:216–229. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnston I.D., McCluskey D.K., Tracey M.C. Mechanical characterization of bulk Sylgard 184 for microfluidics and microengineering. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2014;24:035017. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schluck T., Aegerter C.M. Photo-elastic properties of the wing imaginal disc of Drosophila. Eur. Phys. J. E Soft Matter. 2010;33:111–115. doi: 10.1140/epje/i2010-10580-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Major R.J., Irvine K.D. Localization and requirement for Myosin II at the dorsal-ventral compartment boundary of the Drosophila wing. Dev. Dyn. 2006;235:3051–3058. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aliee M., Röper J.-C., Dahmann C. Physical mechanisms shaping the Drosophila dorsoventral compartment boundary. Curr. Biol. 2012;22:967–976. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Major R.J., Irvine K.D. Influence of Notch on dorsoventral compartmentalization and actin organization in the Drosophila wing. Development. 2005;132:3823–3833. doi: 10.1242/dev.01957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Handke B., Szabad J., Lehner C.F. Towards long term cultivation of Drosophila wing imaginal discs in vitro. PLoS One. 2014;9:e107333. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Restrepo S., Zartman J., Basler K. Cultivation and live imaging of Drosophila imaginal discs. In: Dahmann C., editor. Drosophila. Springer; New York: 2016. pp. 203–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Narciso C.E., Contento N.M., Zartman J.J. A regulated environment for micro-organs defines essential conditions for intercellular Ca2+ waves. bioRxiv. 2016 https://doi.org/10.1101/081869 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu S., Chisholm A.D. A Gαq-Ca2+ signaling pathway promotes actin-mediated epidermal wound closure in C. elegans. Curr. Biol. 2011;21:1960–1967. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.10.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaneuchi T., Sartain C.V., Wolfner M.F. Calcium waves occur as Drosophila oocytes activate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:791–796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1420589112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mammoto T., Mammoto A., Ingber D.E. Mechanobiology and developmental control. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2013;29:27–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101512-122340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buchmann A., Alber M., Zartman J.J. Sizing it up: the mechanical feedback hypothesis of organ growth regulation. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2014;35:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Farge E. Mechanical induction of twist in the Drosophila foregut/stomodeal primordium. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:1365–1377. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00576-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ghannad-Rezaie M., Wang X., Chronis N. Microfluidic chips for in vivo imaging of cellular responses to neural injury in Drosophila larvae. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29869. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yao J., Pilko A., Wollman R. Distinct cellular states determine calcium signaling response. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2016;12:894. doi: 10.15252/msb.20167137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sun S.X., Walcott S. Actin crosslinkers: repairing the sense of touch. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:R895–R896. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.08.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huh D., Matthews B.D., Ingber D.E. Reconstituting organ-level lung functions on a chip. Science. 2010;328:1662–1668. doi: 10.1126/science.1188302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dhumpa R., Truong T.M., Roper M.G. Negative feedback synchronizes islets of Langerhans. Biophys. J. 2014;106:2275–2282. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A Drosophila wing disc imaged in vivo shows formation of an ICW (see Fig. 1 b).

Diaphragm deflections at increasingly applied backpressures (see Fig. 1 c).

ICWs are not observed if FEX is not included in the culture media (see Fig. 4 c).

ICWs form on release of mechanical loading when 15% FEX serum is added to the chemically defined ZB culture medium (see Fig. 4 d).

Release of applied mechanical loading stimulated intercellular Ca2+ waves in the nub-GAL4, UAS-GCaMP6f disc. (see Fig. 5 c).

Knockdown of IP3R abolishes the mechanically induced Ca2+ wave (cross with BL#25937) (see Fig. 5 c).

Knockdown of SERCA abolishes the mechanically induced Ca2+ wave (cross with BL#44581) (see Fig. 5 c).

Knockdown of Inx2 abolishes the release-induced Ca2+ wave (cross with BL#29306) (see Fig. 5 c).

CW activity immediately before application of the mechanical perturbation.