Abstract

Previous studies of the division of labor in colonies of eusocial Hymenoptera (wasps and bees) have led to two hypotheses regarding the evolution of juvenile hormone (JH) involvement. The novel- or single-function hypothesis proposes that the role of JH has changed from an exclusively reproductive function in primitively eusocial species (those lacking morphologically distinct queen and worker castes), to an exclusively behavioral function in highly eusocial societies (those containing morphologically distinct castes). In contrast, the split-function hypothesis proposes that JH originally functioned in the regulation of both reproduction and behavior in ancestral solitary species. Then, when reproductive and brood-care tasks came to be divided between queens and workers, the effects of JH were divided as well, with JH involved in regulation of reproductive maturation of egg-laying queens, and behavioral maturation, manifested as age-correlated changes in worker tasks, of workers. We report experiments designed to test these hypotheses. After documenting age-correlated changes in worker behavior (age polyethism) in the neotropical primitively eusocial wasp Polistes canadensis, we demonstrate that experimental application of the JH analog methoprene accelerates the onset of guarding behavior, an age-correlated task, and increases the number of foraging females; and we demonstrate that JH titers correlate with both ovarian development of queens and task differentiation in workers, as predicted by the split-function hypothesis. These findings support a view of social insect evolution that sees the contrasting worker and queen phenotypes as derived via decoupling of reproductive and brood-care components of the ancestral solitary reproductive physiology.

Keywords: behavioral development, division of labor, methoprene, worker polyethism

Highly eusocial insects are characterized by the evolution of two kinds of adult females with contrasting life histories and morphologies: the reproductive queen and the sterile worker castes (1–3). In addition, the workers of many hymenopteran (wasp, ant, and bee) societies show an age-related division of labor, or age polyethism, in which workers of different ages have different probabilities of performance of particular tasks (2). Here we experimentally address the question of the origin of the worker age polyethism, a key element for understanding the evolution of social organization, by examining two alternative hypotheses that have been proposed to explain it.

In general, in colonies with an age-bias in task performance, younger workers perform within-nest tasks such as brood care, whereas older females perform higher risk tasks such as nest defense and foraging (2). Age polyethism (reviewed in refs. 1, 3, and 4) is most apparent in “highly eusocial” species, or species with large colonies and morphologically discrete workers and queens, but it also occurs in “primitively eusocial” species, those with behaviorally but not morphologically distinct castes (1, 5). Task allocation among an age cohort of workers is known to be sensitive to genetic variation (6, 7) and to colony conditions, such as the size and age of the brood, nest damage, presence of predators and parasites, and the size and age of the worker population (2, 5, 8–13). Given the many factors that can affect task performance, the expression of age polyethism is highly variable both within and between species. In some species, such as honey bees (14), the large-colony swarming wasp Polybia occidentalis (15), and the primitively eusocial wasp Ropalidia marginata (reviewed in ref. 16), workers show a relatively clear change in tasks with age, whereas at another extreme, the workers of the stingless bee Trigona minangkabau have no age-associated change in task, showing instead lifetime task specialization (10). Some species of primitively social genera such as bumblebees and Polistes show a weak or no correlation between age and worker task (1, 11, 17), and such factors as body size and colony composition have a better correlation with the timing of an individual female's change from intra-nest tasks to foraging (17–20).

The existence of the age polyethism alongside responsiveness to colony conditions suggests that selection has acted on some aspect of regulation that changes with age and that influences task performance, yet can respond to changing conditions. The occurrence of age polyethism in at least some species of both primitively and highly social species, and in ants as well as bees and wasps, suggests that it involves an ancient mechanism, possibly present in the solitary ancestors of the social Hymenoptera (3). A candidate mechanism is JH. Studies of honey bees (Apis mellifera) (9, 21–23) and of large-colony, swarming eusocial wasps (P. occidentalis) (15) show a relationship between the age polyethism and JH: methoprene, a JH analog, accelerates the rate at which workers graduate from in-nest tasks to outside tasks. JH also commonly influences ovarian development in insects (24). JH stimulates the production of the egg-yolk protein vitellogenin by the fat body and its uptake by developing oocytes; and, in the brood-care phase of the honey bee worker polyethism, low JH titer is associated with the channeling of vitellogenin into brood-food production rather than eggs (23, 25, 26).

Previous studies have shown contrasting patterns of JH effects on worker task performance and reproduction in different species (reviewed in refs. 22 and 27). In bumblebees JH is associated with ovarian development and the onset of worker behavior (11, 28), but not clearly associated with the ontogeny of worker tasks (11). In honey bees, the correlation of JH with the ontogeny of worker tasks is strong, and JH titer is low in mature queens with highly developed ovaries (reviewed in refs. 22 and 29). But in R. marginata there is a strong age polyethism that has proven refractory to the application of JH (28).

The apparent contrast between bumblebees and honey bees led to the hypothesis that the role of JH has changed during the evolution of the social bees, with the regulation of worker behavior a new function of JH that became possible only when the worker reproductive function was lost (30). This hypothesis, termed the novel-function (3), or the single-function hypothesis (27), has been applied to the evolution of JH function in wasps as well as in bees (15). The novel-function hypothesis makes two testable predictions: (i) JH does not influence worker task behavior in primitively eusocial species with small colonies; it has either one function or the other, but not both; and (ii) JH influence on behavior is limited to species in which the hormone does not influence reproduction. An alternative, termed the split-function or maturational hypothesis (3), is based on the fact that a single hormone can have multiple effects (24), and on a broad survey of data on behavior, reproduction, and JH research on social and solitary hymenopteran species. The split-function hypothesis proposes that the ancestral effects of JH in solitary species likely include both reproduction and associated brood-care behaviors and that these functions are preserved in the queens and the workers, respectively, of social species, albeit additionally influenced by the nutritional state and social circumstances of females. This hypothesis predicts that JH influences both adult reproduction and age-related worker behavior in primitively eusocial species and interprets departures from this pattern, such as JH influence on reproductive determination in the larval rather than the adult phase in highly eusocial species, as derived characteristics.

Limitations of Previous Studies

So far, results on primitively eusocial species with small colonies and on swarming social wasps have not given unequivocal support to either hypothesis. In bumblebees, the age polyethism is weak, and, therefore, measurement of effects of JH on task ontogeny is elusive (there is no clear task sequence that might be accelerated by JH). This lack may actually reflect selection to diminish the effects of age on worker task determination in species where condition-sensitivity is at a premium (see Discussion).

In R. marginata the age polyethism is strong, but JH application to newly emerged females failed to accelerate the age polyethism even though it accelerated the onset of egg laying in the absence of a queen (27). These findings would seem to support the predictions of the novel-function hypothesis, except that the hypothesis assumes an age polyethism to be absent in primitively eusocial species and to be explained in terms of JH when present. Neither hypothesis contemplates the possibility of a well defined age polyethism without the mediation of JH, and the possibility remains that JH is involved: The JH titers of R. marginata workers have not been measured, nor was JH applied to nonworker, nonreproductive (sitter) females (see refs. 16 and 31), so it is not known whether, as in Bombus and Polistes, JH is important for worker behavior to occur.

Similarly, the acceleration by methoprene of task ontogeny in P. occidentalis has been interpreted as support for the novel-function hypothesis (15) but the implication that JH does not affect reproductive development in that species has not been tested. However, the onset of outside-nest tasks coincides with worker ovary resorption (32), suggesting that JH could affect both. Although P. occidentalis resembles honey bees in having a well defined age polyethism and large colony size, it resembles Polistes and other primitively eusocial genera in not having morphologically distinct castes, with caste likely determined, as in other primitively eusocial swarming species, in the adult stage (33–35). The role of JH in reproductive caste determination has not been examined in this or any other swarming social wasp.

Given the inconclusiveness of previous studies, we report tests of the predictions of the novel-function and split-function hypotheses in the tropical primitively eusocial wasp Polistes canadensis.

Materials and Methods

Nests of P. canadensis (Vespidae, Polistini) were located on Barro Colorado Island, Panama, on the eaves of buildings of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and on electric posts at the first 5 miles of the railroad tracks between Gamboa and Frijoles along the Panama canal. We used postemergence nests, where a dominant queen, her adult offspring, and eggs, larvae, and pupae were present. Colonies contained 15–40 workers, and each nest contained >150 cells.

Age-Related Changes in Worker Behavior. Age-related change in worker behavior was monitored in 62 individually paint-marked workers of six late wet-season colonies (three from November 14 to December 21, 1996, and three from September 5 to October 9, 1997). We mapped brood cells to track female emergence dates. Each observation day newly emerged adult females (focal wasps) were individually marked. Data are pooled from 62 individuals of the six nests. Colonies were observed for two periods of 2 h each day: one in the morning (0900–1100 hours) and one in the afternoon (1400–1600 hours), recording the age at first performance (from all six nests, 1,328 acts) and frequency of performance (from the three nests in 1996, 772 acts) of different behaviors. The scan sample method was used, with each marked female's behavior noted during a series of 15-min scan periods, or the time needed to record the activities of all females present. Behaviors recorded were as follows: flight [wasps fly for short periods (1–5 min) and return with no material]; food exchange among adults (receiving and giving prey or nectar); foraging (time of leaving the nest and of returning with nectar, prey, water, or building material); guarding (attacks, or bites when non-nestmates or objects approach the nest); inactivity (resting and walking on nest); nurse behavior (feeding larvae and checking cells with larva), parasite alarm (jerking runs on detection of a parasitoid on or near the nest); escape (retreat when challenged by non-nestmates); and other relatively infrequent tasks (building, pulp foraging, grooming of others, being groomed by others, dominance, and submissive behavior).

To examine the onset of guarding behavior, we introduced a freeze-killed, thawed foreign wasp on a probe to focal wasps daily before the scan sampling of behavior. If the focal wasp bit or attacked the thawed wasp, it was counted as a guard.

As in other studies on age polyethism (5, 8, 36), we recorded frequency of performance of each behavior at different ages. We also recorded the age at which a behavior was first observed (age at onset). This parameter describes more clearly the age-related division of labor for cross-taxonomic comparisons (14, 37) than do samples giving averages of worker age classes. Age classes may obscure critical switch points by lumping a range of the ages at which switching occurred into one measure.

Methoprene Effect on Worker Reproduction and Behavior. To examine whether age-related behavioral change is influenced by JH, we tested the effect of methoprene on onset of guarding and foraging, two behaviors found to occur only in relatively old workers (see Results). Methoprene is known to have behavioral and physiological effects similar to those of JH in the Hymenoptera (15, 21, 38, 39). In addition, there is evidence from studies with Drosophila that methoprene acts in ways similar to JH at the cellular level (40, 41). Preliminary tests (data not shown) indicated that the highest dose that did not cause increased mortality in comparison to the acetone or blank treated groups was 25 μg of methoprene per μl of acetone. We used this maximum tolerated dose in this experiment.

In three nests with active queens, we marked 16 pairs of same-age (newly emerged) individuals during the period from September 12 to October 1, 1997. Individuals were paired only when they emerged on the same nest, within 24 h of each other. Each individual in a pair was allocated randomly to a control or a treatment (methoprene) group. On their first day after emergence, one-half of the wasps in the control group received a topical 1 μl of acetone treatment, and the other one-half were only handled and marked (blank). They were then returned to their nests. There were no mortality differences among the treatment (1/16), blank (1/9), and acetone groups (1/8), indicating that neither the hormone analog nor the acetone treatment were causing increased mortality. Neither the acetone nor the blank group differed in other behavioral or physiological measures (data not shown). Hence the two are pooled, along with an additional untreated wasp, as the “control group” (n = 17 females). The treatment and control groups were marked with different colors but colors were randomly switched across nests to permit blind observations.

We examined the onset of guarding behavior by introduction of a dead foreign wasp, as described above. In these assays, only attack or bite was considered as guarding behavior. Foraging behavior by control and treatment wasps was also recorded daily for 2 h.

At the end of the 12-day period of behavioral observations following methoprene application, the surviving control and treatment wasps were collected and dissected to assess ovary development (mean length of the six largest oocytes) (38, 42) and to determine the presence of sperm in the sperm-storage organ or spermatheca (42).

Measurement of JH Titers of Individual Workers and Gynes. In 1997 we measured hemolymph JH titers of June and July workers of different behavioral categories, including nurses (females which visited brood cells and did not guard); foragers (females which returned to colonies with nectar or prey); and guards (females which responded to the guarding assay and which seldom or never foraged). We also measured JH titers of newly emerged (1-day-old) females (August 8–17); and reproductive queens (females observed ovipositing) (October 1–11).

Hemolymph samples were collected by cutting the antennae of chilled wasps and applying a calibrated, baked glass capillary to the wound. The hemolymph collected was then expelled in to a tube containing 500 μl of acetonitrile. The samples were stored at -20°C until radioimmunoassays (RIA) were performed to determine JH titers. JH-III titer was determined with a JH-RIA previously used for other Hymenoptera (21, 43, 44). JH is a sesquiterpenoid hormone with six types found in different insect orders (24). JH-III is common to all insects and is the only type found in Hymenoptera to date (45).

Results

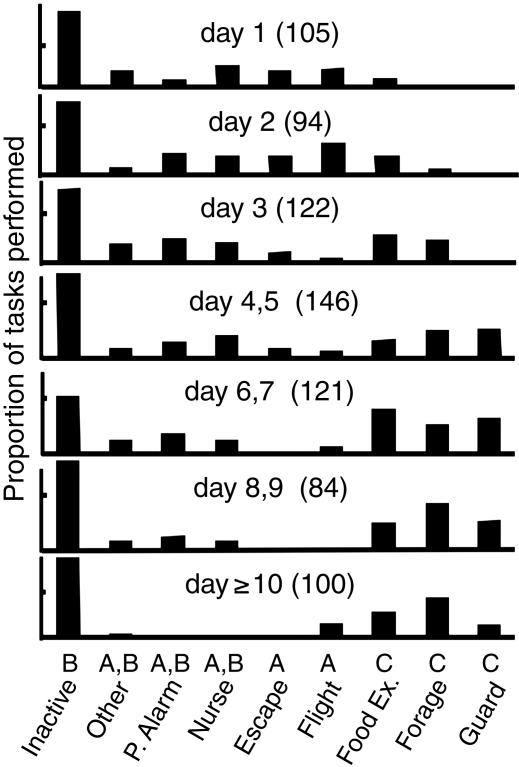

Age-Related Changes in Worker Behavior. Escape, flight, and nurse behavior were more frequently performed by younger individuals (<4 days old), and guarding, foraging, and food exchange were performed more frequently by older individuals (Fig. 1). Frequencies for inactive (resting and patrolling) and parasite alarm behaviors were independent of age. Building was performed only by a very small number of the focal wasps (a total of three individuals observed on five bouts of foraging for pulp and building). Hence, we are not including this behavior separately in the analysis of age-related worker division of labor.

Fig. 1.

Frequency of task performance by workers in different age groups. There is a statistically significant effect of age on frequency of performance of different tasks (df = 48, X2 = 236.65, P < 0.0001) Tasks with different letters show statistically different patterns of performance with age in post hoc comparisons (P < 0.05): A, relatively common in young individuals; B, relatively unchanging across age categories; and C, relatively common in older individuals. The number of tasks observed for each age group is in parentheses. P. Alarm, parasite alarm; Food Ex., food exchange.

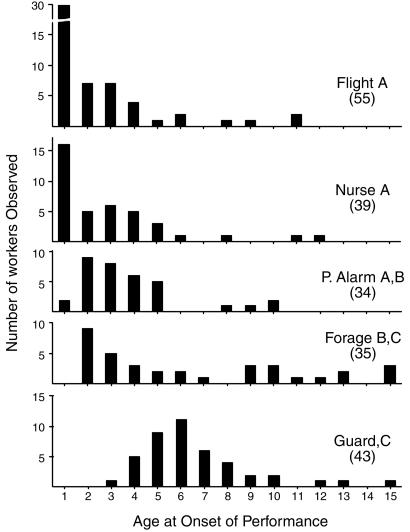

All tasks except transition to foraging were strongly age-dependent using the narrower criterion of age-at-onset of behavior (Fig. 2). Guarding was strongly age-related, starting between 4 and 11 days of age (mean ± SE, 8 ± 0.5, n = 55). Most individuals at guarding age and older can be induced to guard (attack or bite) by using the standard assay (see Materials and Methods). Because guarding has a clear age at onset (Fig. 2), and is easily elicited by a standard test, it proved especially useful as a behavioral indicator for measuring the response of an age-dependent task to hormone treatments (below).

Fig. 2.

Age at onset of task performance for five tasks. Number of wasps observed at the first performance of each task are in parentheses. There is a statistically significant effect of task on age of onset (ANOVA, df = 4, F = 19.233, P < 0.0001). Tasks with different letters showed statistically different patterns of onset with age in post hoc comparisons (Tukey's HSD, P < 0.05): A, relatively early onset, including common in newly emerged females; B, relatively early onset but uncommon in newly emerged individuals; and C, relatively late onset. P. Alarm, parasite alarm.

In contrast, flight, foraging, and nursing were performed by at least some newly emerged wasps (Fig. 2). Although foraging differed from flight, nursing, and parasite alarm behaviors in terms of frequency of performance (Fig. 1), it was statistically not different from parasite alarm behavior in terms of age at onset of behavior. Furthermore, there were individual differences in foraging tasks independent of age: Some focal wasps never foraged. Only ≈60% of the newly emerging wasps made the transition to foraging by the age of 14 days. Twenty-nine (63%) of 46 females that stayed for 14 days on the nest foraged; and only six (40%) of 15 wasps that disappeared from the nest before the age of 14 days foraged. We do not know whether these nonforagers of short duration on their natal nests died, found new nests, or underwent a period of inactivity away from nests during the dry season. Most worker tasks were initiated before the age of 14 days; only 2% of first-onset events occurred after that age.

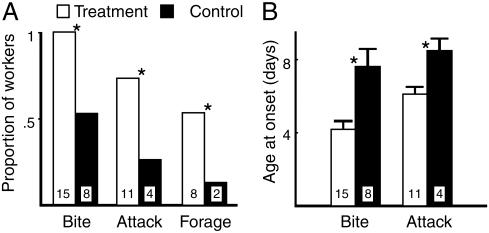

JH Analog Effect on Worker Reproduction and Behavior. Methoprene affects the development of guarding behavior. Onset of guarding was earlier in the treatment group (Fig. 3A). There was also a higher proportion of treatment group wasps among those that were first to bite or attack in the guarding assay (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Juvenile hormone analog, methoprene, influenced performance of guarding (bite and attack) and foraging behaviors. (A) Treatment group wasps were overrepresented in the group of wasps initiated guarding and foraging behaviors. *, Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) in Fisher's exact tests for proportions of workers initiating the behaviors. The n is given in the bars. (B) Bite or attack behavior was initiated at younger ages by wasps in the treatment group (control, age at first bite or attack ± SE, 9 ± 0.59 days; treatment, 5.5 ± 0.27; ncontrol = 8, ntreatment = 8, Wilcoxon signed-rank test, z = -2.536, P < 0.02).

Methoprene also has a significant effect on the age at onset of foraging: More workers in the treatment group started foraging during the 12-day observation period than in the control group (Fig. 3B). The relatively delayed onset of foraging in the control group is indicated by the low numbers that started foraging during the observation period. Methoprene application did not affect the reproductive condition of newly emerged females as observed upon dissection 12 days after application. Treatment and control groups did not differ in frequency of mated individuals (Fisher's exact test, P > 0.9, mated/dissected; treatment, 5/12; control, 5/11) or extent of ovarian development (paired t test, nt,c = 10, df = 9, t = 1.378, P = 0.2; treatment, mean ± SE, 0.256 ± 0.09; control, mean ± SE, 0.4 ± 0.12).

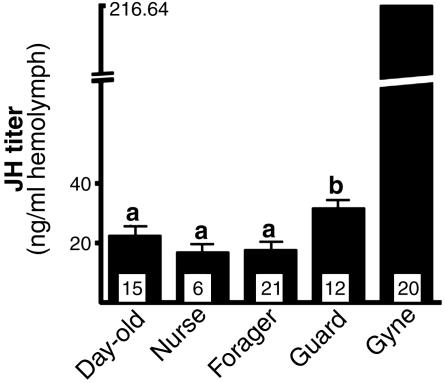

JH Titers of Newly Emerged Females, Workers, and Gynes. JH regulation of guarding behavior in workers was supported by the observation of higher titers in guards than in other workers (Fig. 4). Also in agreement with other studies on JH regulation of reproduction in Polistes foundresses, we found the highest JH titers in reproductives (Fig. 4), including queens from postemergence nests (134.3 ± 31.32 ng of JH per ml of hemolymph, n = 6); queens of preemergence single foundress nests (231.48 ± 86.44 ng per ml, n = 6); and queens of multiple foundress nests (267.25 ± 75.76 ng per ml, n = 8). There were no statistically significant differences in JH titers of these three types of reproductives.

Fig. 4.

Juvenile hormone titers of workers and gynes. Gynes were compared to all workers and had an order of magnitude higher JH titers (SEs for gynes given in text). Worker groups, 1-day-old, nurse, forager, and guard were compared among themselves. Groups labeled “a” were not significantly different from each other. The group labeled “b” was significantly different from all others. The n for each group is indicated at the base of the bars.

Foragers had low JH titers, similar to 1-day-old females and other workers (nurses), which neither forage nor guard (Fig. 4). The JH titers of foragers were measurable, however, so it is possible that some JH is required for onset of foraging and other worker activities (see below).

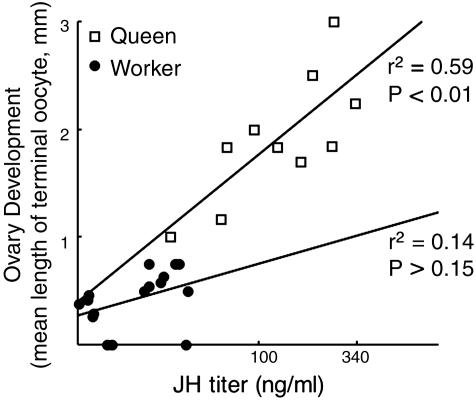

In agreement with the methoprene study, JH titer in workers did not correlate with extent of ovary development (log transformed mean length of terminal oocytes vs. JH titer; F = 1.299, df = 1, P > 0.27, n = 18, Fig. 5) or mating status (JH titers of mated vs. unmated workers; F = 0.224, df = 1, P > 0.63, nm,u = 15,18. JH titer in egg-laying queens, by contrast, was highly correlated with ovarian development (r = 0.83, n = 11, P < 0.002, Fig. 5). Queen JH titers were markedly higher than those of the workers. The difference in JH titers was proportional to the ovary-development difference between them (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Correlation of juvenile hormone titers and ovary development in workers (n = 18) and gynes (n = 11). Additional statistics are in the text.

Discussion

Our results indicate a relationship between JH and both age-related change in worker behavior and reproductive development of queens in the primitively eusocial wasp Polistes canadensis. This finding contradicts the novel- or single-function hypothesis that, influence on behavioral development is a newly evolved role for JH in the highly eusocial Hymenoptera by suggesting that both functions may be present in the same species.

In honey bees, where JH increases with worker age, relatively high JH is associated with foraging behavior, and JH, although not required for the transition to foraging, accelerates its onset (23). In the population of this study, behavioral data showed an early onset of foraging in many workers (Fig. 2). Therefore, it is not surprising that the JH titers of foragers were found to be low, comparable to those of newly emerged females and nurses, and lower than in older females functioning as guards. Early onset of foraging and late onset of guard behavior has also been observed in social wasps of the genus Vespula (ref. 1, after ref. 46).

Why was the correlation between ovarian response and JH titer greater in queens than in workers (Fig. 5)? This difference may be explained by the poorer nutritional state of worker females and may indicate a mechanism by which JH effects on reproduction (ovaries) and brood care (worker behavior) could have been decoupled during evolution as proposed by the split-function hypothesis. A protein diet or protein stored in the fat body is required for egg production. In Polistes socially dominant queens have a nutritional advantage relative to workers. They spend less energy on brood care, foraging, and colony defense, and are preferentially fed by nestmates (47, 48), in addition to being better endowed with stored nutrients in the fat body as part of a caste-determination process influenced by larval nutrition (49). This trophic advantage would enable queens to respond to elevated JH with elevated ovarian development, whereas workers, whose nutrient stores are known to become depleted by a period of foraging (50), may be less able to increase ovarian development in response to JH. The lack of correlation between JH titer and ovarian development in workers may also be due to variation in their nutritional state, whether in the larval (50) or adult stage. The relation between worker activity, nutritional status, and ovarian development in social insects is well known (48, 50–55).

A possible interpretation of the increased expression of foraging in methoprene-treated wasps and the failure to forage of numerous females by age 12 days is that a portion of newly emerging females in this population of P. canadensis during the periods (late wet season) of our observations and experiments were in reproductive diapause, characterized by JH below detection limit of RIA, and lack of ovarian development and foraging behavior (n = 6; not included in Fig. 5 because JH levels that cannot be measured by RIA). Methoprene treatment may have broken the diapause, increasing the number of females that foraged by age 12 days. Alternatively, nutritional differences between the experimental colonies and the unmanipulated colonies observed at about the same time of year (Fig. 2) may account for differences in their frequencies of transition to foraging; well nourished females may persist longer at the more queen-like nest tasks (e.g., see ref. 25). The mean age for onset of guarding by the treatment group was 5.5 ± 0.59 days, about the same as that for attack behavior on unmanipulated nests (≈6 days, Fig. 3A), whereas the control females that emerged simultaneously had an unusually long (9 ± 0.59 days) period before expressing defensive behavior. The absence or delay of worker activity in the controls could also indicate diapause, broken by methoprene treatment in the experimental group. In temperate species of primitively eusocial wasps (Polistes) and bees (Bombus) “caste determination” in the emerging adult females is achieved by the presence or absence of JH-mediated diapause, which when broken by JH application produces both worker behavior and ovarian development (11, 28, 56). Such findings accord with those of the present study and the split-function hypothesis in suggesting that both worker behavior and reproduction in primitively eusocial insects are influenced by JH.

The possibility of diapause in the population of the present study is also suggested by the rarity of building behavior, which correlates with ovarian development in at least some Polistes species and other social wasps (57, 58), in the young females of our late-wet-season observation nests. Even though the population of adult females is high during this period just before the onset of the dry season, population-wide oviposition rates are low; and nest-initiation rates are low during November and December (59). Although JH-mediated physiological diapause has not been demonstrated in tropical wasps a diapause-like state has been observed in females P. instabilis in Costa Rica (60) which, like the wasps of our Panamanian study population, experience a strong dry season. Females of R. marginata in Bangalore, India (13°N latitude) undergo a reproductive arrest during relatively cool winter months (61), raising the possibility that the presence of idle or “sitter” females in some tropical social wasps (16, 31, 62) could involve a JH-mediated polyphenism.

Compared to that of A. mellifera, the age polyethism is weak in Bombus (ref. 11; reviewed in ref. 63) and in Polistes (e.g., present study), whereas it is relatively well defined in vespiary colonies of R. marginata (5) and in P. occidentalis (64), a large-colony primitively eusocial swarming wasp. The relatively well defined JH-correlated age polyethism of honey bees and P. occidentalis may be due at least in part to a lesser influence of confounding variables in their large colonies, where there is a greater supply of workers of all ages available to meet the task-distribution demands of the colony, permitting a more consistent expression of age-related and JH effects on behavior. This “stable supply and demand” hypothesis, predicting a more consistent expression of age polyethism in large colonies (see also ref. 65), is supported by the finding that under certain demographic conditions workers in colonies of Apis show a less strict correlation between age and task than in typical colonies (66). They show, moreover, a consistent response to JH, with JH titers appropriate to the task, indicating that the mechanism of adjustment is a change in JH synthesis in response to conditions, producing a physiological age different from their chronological age (59, 67, 68). The age polyethism of R. marginata correlates best with relative, rather than absolute, age (5), indicating that individuals adjust their behavioral ontogeny to the task-performance (age-cohort) supply, as in the JH-independent differentiation pathway of Amdam and Omholt (26). The stable-supply and demand hypothesis also predicts that the age polyethism should be more consistently expressed in favorable laboratory conditions than in wild colonies more exposed to fluctuating environmental conditions. Stable favorable conditions may contribute to the well defined age polyethism observed in vespiary colonies of R. marginata (5), which are protected from parasites and predators and provided with ad libitum food and nesting material (16), optimal conditions for exposing an age polyethism if it exists. Ad libitum food may also explain why the R. marginata age polyethism is insensitive to methoprene application. If, as hypothesized by the double-repressor hypothesis for regulation of the honey bee age polyethism (26), rising JH affects worker behavioral transitions in part because of the exhaustion of nutritional stores and (lowered) vitellogenin production, then high nutritional status would lower the effect of the JH-dependent pathway, while allowing the JH-independent pathway mediated by external factors such as relative age of nestmates (69, 70) to predominate.

JH titer should be seen as one factor among several that can affect the highly plastic task performance of social insect workers (4, 13, 71). Others, such as ecdysteroids, are known to correlate, along with JH titer, with degree of ovarian development in P. gallicus (20) and B. terrestris (72, 73) but not in highly eusocial bees (74). Our findings support the view of social insect evolution that sees the unique, derived phenotypes of social species as derived via reorganization of ancestral, solitary traits (3, 25). Future comparative studies of JH function and evolution need to include studies of solitary species, especially those with progressive provisioning and extended brood care likely to resemble the reproductive cycles of the ancestors of social species (3), to establish the ancestral baseline from which specialized variants in JH function may have been derived.

Acknowledgments

We thank Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute staff for help during experiments, William Wcislo for discussions about experiments, and Giray laboratory members, Gene E. Robinson, and Diane Wheeler for reviewing the manuscript. We also acknowledge financial and other support from Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (T.G., M.J.W.-E., and M.G.), National Institutes of Health–Support of Continuous Research Excellence (T.G.), Center for Research Excellence in Science and Technology Program–Center for Applied Tropical Ecology and Conservation–National Science Foundation (T.G.), JA–PR (T.G.), Ministero degli Affari Esteri, and Universitá di Milano (M.G.). Voucher specimens were deposited to Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute and University of Panama.

Author contributions: T.G. and M.J.W.-E. designed research; T.G., M.G., and M.J.W.-E. performed research; T.G., M.G., and M.J.W.-E. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; T.G., M.G., and M.J.W.-E. analyzed data; and T.G. and M.J.W.-E. wrote the paper.

Abbreviation: JH, juvenile hormone.

References

- 1.Jeanne, R. L. (1991) in The Social Biology of Wasps, eds. Ross, K. G. & Matthews, R. W. (Comstock, Ithaca, NY), pp. 191-231.

- 2.Wilson, E. O. (1971) The Insect Societies (Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, MA).

- 3.West-Eberhard, M. J. (1996) in Natural History and Evolution of Paper Wasps, eds. Turillazzi, S. & West-Eberhard, M. J. (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford), pp. 290-317.

- 4.Bloch, G., Wheeler, D. E. & Robinson, G. E. (2002) in Hormones, Brain and Behavior (Elsevier Science, St. Louis, MO), Vol. III, pp. 195-235. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naug, D. & Gadagkar, R. (1998) Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 42, 37-47. [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Donnell, S. (1996) Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 38, 83-88. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Page, R. E., Jr. & Robinson, G. E. (1990) Adv. Insect Physiol. 23, 118-167. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oster, G. F. & Wilson, E. O. (1978) Caste and Ecology in the Social Insects (Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton). [PubMed]

- 9.Robinson, G. E. (1992) Annu. Rev. Entomol. 37, 637-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inoue, T., Salmah, S. & Sakagami, S. F. (1996) Jpn. J. Entomol. 64, 641-668. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cameron, S. A. & Robinson, G. E. (1990) Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 83, 626-631. [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Donnell, S. & Jeanne, R. L. (1992) Insect Soc. 39, 73-80. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calabi, P. (1988) in Advances in Myrmecology, ed. Trager, J. C. (Brill, Leiden, The Netherlands), pp. 237-258.

- 14.Winston, M. L. (1987) The Biology of the Honey Bee (Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, MA).

- 15.O'Donnell, S. & Jeanne, R. L. (1993) Physiol. Entomol. 18, 189-194. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gadagkar, R. (2001) The Social Biology of Ropalidia marginata (Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, MA).

- 17.Cameron, S. A. (1989) Ethology 80, 137-151. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brian, A. D. (1952) J. Anim. Ecol. 21, 223-240. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Free, J. B. (1955) Insect Soc. 2, 195-212. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Röseler, P.-F. & Van Honk, C. G. J. (1990) in Social Insects: An Evolutionary Approach to Castes and Reproduction, ed. Engels, W. (Springer-Verlag, Berlin). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Robinson, G. E. (1987) Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 20, 329-338. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robinson, G. E. & Vargo, E. L. (1997) Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 35, 559-583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sullivan, J. P., Jassim, O., Fahrbach, S. E. & Robinson, G. E. (2000) Horm. Behav. 37, 1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nijhout, H. F. (1994) Insect Hormones (Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton).

- 25.Amdam, G. V., Norberg, K. & Page, R. E., Jr. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 11350-11355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amdam, G. V. & Omholt, S. W. (2003) J. Theor. Biol. 223, 451-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agrahari, M., Gadagkar, R. (2003) J. Insect Physiol. 49, 217-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Röseler, P.-F. (1976) in Phase and Caste Determination in Insects: Endocrine Aspects. Symposium of the Section Physiology and Biochemistry of the XV International Congress of Entomology, ed. Luscher, M. (Pergamon, Oxford), pp. 55-62.

- 29.Fahrbach, S. E., Giray, T. & Robinson, E. G. (1995) Neurobiol. Learn. Memory 63, 181-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robinson, G. E., Strambi, C., Strambi, A. & Huang, Z.-Y. (1992) Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 87, 471-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gadagkar, R. & Joshi, N. V. (1982) Anim. Behav. 31, 26-31. [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Donnell, S. (2001) Behav. Ecol. 12, 353-359. [Google Scholar]

- 33.West-Eberhard, M. J. (1978) Science 220, 441-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gastreich, K. R., Strassmann, J. E. & Queller, D. C. (1993) Ethol. Ecol. Evol. 5, 529-539. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strassmann, J. E., Solís, C. R. & Hughes, C. R. (1997) Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 40, 71-77. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Post, D. C., Jeanne, R. L., Erickson, E. H., Jr. (1988) in Interindividual Behavioral Variability in Social Insects, ed. Jeanne, R. L. (Westview, Boulder, CO), pp. 283-321.

- 37.Hölldobler, B. & Wilson, E. O. (1990) The Ants (Belknap, Cambridge, MA).

- 38.Bloch, G., Borst, D. W., Huang, Z.-Y., Robinson, G. E. & Hefetz, A. (1996) Physiol. Entomol. 21, 257-267. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giray, T. & Robinson, G. E. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 11718-11722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shemshedini, L. & Wilson, T. G. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 2072-2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ashok, M., Turner, C. & Wilson, T. G. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 2761-2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.West-Eberhard, M. J. (1975) Cespedesia 4, 245-267. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang, Z. Y., Robinson, G. E. & Borst, D. W. (1994) J. Comp. Physiol. A 174, 731-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang, Z. Y. & Robinson, G. E. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 11726-11729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hagenguth, H. & Rembold, H. (1978) Z. Naturforsch. 33, 847-850. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Akre, R. D., Garnett, W. B., MacDonald, J. F., Greene, A. & Landolt, P. (1976) J. Kansas Entomol. Soc. 49, 63-84. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pardi, L. (1948) Physiol. Zool. 21, 1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hunt, J. H. & Nalepa, C. A. (1994) Nourishment and Evolution in Insect Societies (Westview, Boulder, CO).

- 49.O'Donnell, S. (1998) Annu. Rev. Entomol. 43, 323-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O'Donnell, S. & Jeanne, R. L. (1995) Experientia 51, 749-752. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Duchateau, M. J. & Velthuis, H. H. W. (1988) Behaviour 107, 3-4. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pardi, L. (1939) Redia 25, 87-288. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martinez, T. & Wheeler, D. (1991) Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 17, 143-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Markiewicz, D. A. & O'Donnell, S. (2001) J. Comp. Physiol. A 187, 327-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wheeler, D. E. (1996) Annu. Rev. Entomol. 41, 407-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bohm, M. F. K. (1972) J. Insect Physiol. 18, 1875-1883. [Google Scholar]

- 57.West-Eberhard, M. J. (1969) Misc. Pub. Mus. Zoo. Univ. Mich. 140, 1-101. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Robinson, G. E., Page, R. E., Strambi, A. & Strambi, C. (1989) Science 246, 109-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pickering, J. (1980) Ph.D. thesis (Harvard Univ., Cambridge, MA).

- 60.Hunt, J. H., Brodie, R. J., Carithers, T. P, Goldstein, P. Z. & Janzen, D. H. (1999) Biotropica 31, 192-196. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gadagkar, R., Bhagavan, S., Malpe, R. & Vinutha, C. (1991) Entomon 16, 167-174. [Google Scholar]

- 62.West-Eberhard, M. J. (1981) in Natural Selection and Social Behavior: Recent Research and New Theory, eds. Alexander, R. D. & Tinkle, D. W. (Chiron, NY), pp. 3-17.

- 63.Michener, C. D. (1974) The Social Behavior of the Bees (Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, MA).

- 64.Jeanne, R. L., Downing, H. A., Post, D. C. (1988) in Inter-Individual Behavioral Variability in Social Insects, ed. Jeanne, R. L. (Westview, Boulder, CO), pp. 323-357.

- 65.Karsai, I., Wenzel, J. W. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 8665-8669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gary, N. (1975) in The Hive and the Honey Bee (Dadant, Hamilton, IL), pp. 185-264.

- 67.Giray, T., Huang, Z. Y., Guzman-Novoa, E. & Robinson, G. E. (1999) Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 47, 17-28. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Giray, T., Guzman-Novoa, E., Aron, C. W., Zelinsky, B., Fahrbach, S. E. & Robinson, G. E. (2000) Behav. Ecol. 11, 44-55. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Naug, D. & Gadagkar, R. (1998) Insectes Soc. 45, 247-254. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Naug, D & Gadagkar, R. (1999) J. Theor. Biol. 197, 123-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hartfelder, K. & Engles, W. (1998) Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 40, 45-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bloch, G., Borst, D. W., Huang, Z.-Y., Robinson, G. E., Cnaani, J. & Hefetz, A. (2000) J. Insect Physiol. 46, 47-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bloch, G., Hefetz, A. & Hartfelder, K. (2000) J. Insect Physiol. 46, 1033-1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hartfelder, K., Bitondi, M. M. G., Santana, W. C. & Simões, Z. L. P. (2002) Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 32, 211-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]