Dietary polyphenols exert a range of beneficial outcomes on the intestinal microbiota, and in metabolic syndrome, such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anticarcinogenic, and antidiabetic effects. Research by Roopchand and colleagues demonstrated that concord grape polyphenols (GP) led to changes in the gut microbiota and reduction in conditions associated with metabolic syndrome arising from high-fat diet (HFD) in mice (1). Mice were divided into three groups and fed with HFD only or HFD supplemented with 10% soy-protein isolate (SPI) or HFD supplemented with 10% GP-SPI, respectively, for 13 weeks. When compared to the other diet groups, mice on the GP-SPI diet had lower body weight and adiposity though the food intake was similar across the groups (1).

Also, mice on the GP-SPI diet reduced markers of systemic inflammation as IL-6 was undetectable, and low levels of TNF-α and bacterial lipopolysaccharide was detected in the serum in comparison to the SPI group. However, levels of cholesterol, triglycerides, and IL-1β in the serum were not significantly different from mice fed with the SPI diet (1).

So, how did the GP-based diet impact the gastrointestinal tract? Just as observed in the serum, lower expression of TNF-α and IL-6 was detected in the colon. Fasting-induced adipose factor, a circulating lipoprotein lipase inhibitor, was significantly increased in the ileum compared to the SPI diet (1). This suggests that the GPs may aid in the suppression of fatty acid storage thereby attenuating the effects of diet-based metabolic syndrome. Further evidence in the ileum was provided by increased gene expression of proglucagon, a precursor of proteins associated with production of insulin and maintenance of gut barrier integrity (1). However, it would have been nice to see how these evidences compared with the controls used in this study as the data were not shown. Glut2, a gene for glucose transport, was also significantly lower in the jejunum tissue when compared to the mice on the SPI-diet (1).

Grape polyphenol-based diet led to decreased ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes and significant increase in the relative abundance of Akkermansia muciniphila in the cecal and fecal microbiota (1). This decrease in the proportion of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes has been reported in other diet-induced obesity studies (2, 3). However, another study did not find a causal effect of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio in relation to obesity (4).

Similarly, the effects of dietary polyphenol from cranberry extract were evaluated in mice fed with high-fat/high-sucrose diet for 8 weeks (5). Cranberry extract prevented weight gain, enhanced insulin sensitivity, and reduced triglycerides in the jejunum. Cranberry extract-supplemented diet also led to a dramatic increase in Akkermansia (5). Furthermore, a reduction in body weight gain and insulin was observed in rats fed with a standard-chow diet supplemented with pterostilbene (6). Changes in the gut microbiota with increase in Akkermansia were also observed (6).

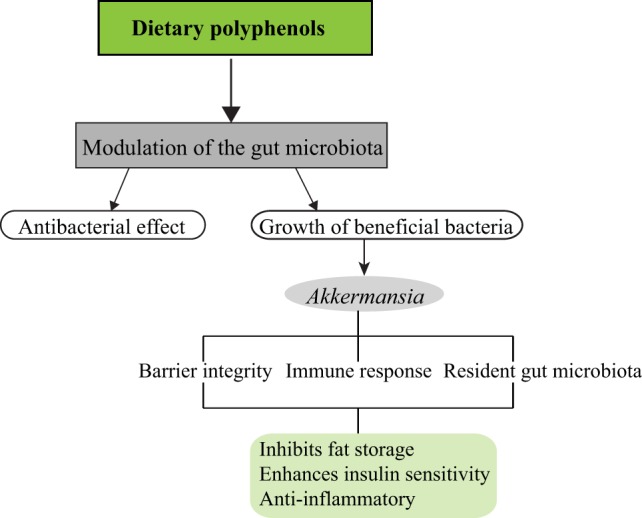

Of what importance is Akkermansia in the intestinal microbiota and how does it influence diet-induced obesity and metabolic disorders? A. muciniphila is a mucin degrading bacterium present in the mucus layer of the intestinal epithelium and may represent 3–5% of the gut microbiota in healthy adults (7). Several studies have shown an increase in Akkermansia in diet-induced obesity studies and correlates with the reduction of weight gain, adiposity, and improved glucose tolerance (1, 5, 8). Administration of live A. muciniphila reversed the symptoms of obesity and metabolic syndrome in HFD mice by reducing adiposity, inflammatory markers, insulin resistance, and improved gut barrier (7). Recently, it was shown that the introduction of capsaicin, a dietary polyphenol, led to an abundance of the genera Akkermansia, Bacteroides, and Coprococcus in mice fed with HFD and a decrease in weight gain (9). Potential mechanisms by which Akkermansia influences the host microbiota leading to these beneficial outcomes are depicted below (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Dietary polyphenols and impact on the gut microbiota. Different classes of dietary polyphenols modulate the gut microbiota by various means. This could be by exerting antibacterial effect as observed in flavonoids on six pure cultures of intestinal bacteria (10) and stimulating the growth of beneficial bacteria in the gut microbiota such as Akkermansia. Akkermansia, in turn, generates short-chain fatty acids from the breakdown of mucins, which stimulates the goblet cells to produce more mucus thereby preserving/replenishing the intestinal barrier integrity. Mucus secretion is associated with the activation of the immune system, by preventing increased interaction of microbe-associated molecular patterns with intestinal epithelial cells, and stimulating other immune responses. This helps to reduce intestinal inflammation. Akkermansia may also influence resident gut bacteria by acting as an oxygen scavenger thereby, creating a favorable environment for the growth of strict anaerobes, which could have a synergistic effect on the host.

These and other studies suggest that dietary polyphenols play a role in the modulation of the gut microbiota that may favor positive outcomes. Understanding the mechanism of action of dietary polyphenols is likely to be key in the development of new diet-based therapies. This is because two different polyphenols can give complementary and dissimilar effects on the gut microbiota as observed in black tea and red wine grape extracts (11). As such, more studies are needed to unravel the bioactivity of this class of xenobiotics to fully understand their effects on the host.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Roopchand DE, Carmody RN, Kuhn P, Moskal K, Rojas-Silva P, Turnbaugh PJ, et al. Dietary polyphenols promote growth of the gut bacterium Akkermansia muciniphila and attenuate high-fat diet-induced metabolic syndrome. Diabetes (2015) 64(8):2847. 10.2337/db14-1916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Gordon JI. An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature (2006) 444(7122):1027–31. 10.1038/nature05414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turnbaugh PJ, Bäckhed F, Fulton L, Gordon JI. Diet-induced obesity is linked to marked but reversible alterations in the mouse distal gut microbiome. Cell Host Microbe (2008) 3(4):213–23. 10.1016/j.chom.2008.02.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duncan SH, Lobley GE, Holtrop G, Ince J, Johnstone AM, Louis P, et al. Human colonic microbiota associated with diet, obesity and weight loss. Int J Obes (2008) 32(11):1720–4. 10.1038/ijo.2008.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anhê FF, Roy D, Pilon G, Dudonné S, Matamoros S, Varin TV, et al. A polyphenol-rich cranberry extract protects from diet-induced obesity, insulin resistance and intestinal inflammation in association with increased Akkermansia spp. population in the gut microbiota of mice. Gut (2015) 64(6):872. 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Etxeberria U, Hijona E, Aguirre L, Milagro FI, Bujanda L, Rimando AM, et al. Pterostilbene-induced changes in gut microbiota composition in relation to obesity. Mol Nutr Food Res (2017) 61(1):1500906. 10.1002/mnfr.201500906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Everard A, Belzer C, Geurts L, Ouwerkerk JP, Druart C, Bindels LB, et al. Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2013) 110(22):9066–71. 10.1073/pnas.1219451110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shin NR, Lee JC, Lee HY, Kim MS, Whon TW, Lee MS, et al. An increase in the Akkermansia spp. population induced by metformin treatment improves glucose homeostasis in diet-induced obese mice. Gut (2014) 63(5):727. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shen W, Shen M, Zhao X, Zhu H, Yang Y, Lu S, et al. Anti-obesity effect of capsaicin in mice fed with high-fat diet is associated with an increase in population of the gut bacterium Akkermansia muciniphila. Front Microbiol (2017) 8:272. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duda-Chodak A. The inhibitory effect of polyphenols on human gut microbiota. J Physiol Pharmacol (2012) 63(5):497–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kemperman RA, Gross G, Mondot S, Possemiers S, Marzorati M, Van de Wiele T, et al. Impact of polyphenols from black tea and red wine/grape juice on a gut model microbiome. Food Res Intern (2013) 53(2):659–69. 10.1016/j.foodres.2013.01.034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]