Abstract

The mitochondrial genome (mt genome) provides important information for understanding molecular evolution and phylogenetics. As such, the two complete mt genomes of Ampelophaga rubiginosa and Rondotia menciana were sequenced and annotated. The two circular genomes of A. rubiginosa and R. menciana are 15,282 and 15,636 bp long, respectively, including 13 protein-coding genes (PCGs), two rRNA genes, 22 tRNA genes and an A + T-rich region. The nucleotide composition of the A. rubiginosa mt genome is A + T rich (81.5%) but is lower than that of R. menciana (82.2%). The AT skew is slightly positive and the GC skew is negative in these two mt genomes. Except for cox1, which started with CGA, all other 12PCGs started with ATN codons. The A + T-rich regions of A. rubiginosa and R. menciana were 399 bp and 604 bp long and consist of several features common to Bombycoidea insects. The order and orientation of A. rubiginosa and R. menciana mitogenomes with the order trnM-trnI-trnQ-nad2 is different from the ancestral insects in which trnM is located between trnQ and nad2 (trnI-trnQ-trnM-nad2). Phylogenetic analyses indicate that A. rubiginosa belongs in the Sphingidae family, and R. menciana belongs in the Bombycidae family.

Introduction

Insect mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is a double-stranded, circular molecule that is 14–19 kb in length and contains 13 PCGs: subunits 6 and 8 of the ATPase (atp6 and atp8), cytochrome c oxidase subunits 1–3 (cox1–cox3), cytochrome B (cob), NADH dehydrogenase subunits 1–6 and 4 L (nad1–6 and nad4L). It also contains two rRNA genes, small and large subunit rRNAs (rrnL and rrnS), 22 tRNA genes and a non-coding element termed the A + T-rich region1. The A + T-rich region has a higher level of sequence and length variability than other regions of the genome2–5 and regulates the transcription and replication of mt genomes6. As an informative molecular marker, mtDNA can provide important information for rearrangement patterns and phylogenetic analysis due to its rapid evolutionary rate and lack of genetic recombination7. Therefore, mtDNA has been widely used for diverse evolutionary studies among species8.

Recent advances in sequencing technologies have led to the rapid increase in mt genome data in GenBank, including Bombycoidea mt genomes. Bombycoidea is a superfamily of moths that contains the silk moths, emperor moths, sphinx moth, and relatives9. Some complete mt genomes of Bombycoidea insects are currently available in GenBank (Table 1). Several representative families were studied in this paper. Two families, Bombycidae and Saturniidae, are silk-producing insects with economic values in Bombycoidea10. The Sphingidae are a family of Bombycoidea, commonly known as hawk moths, sphinx moths, and hornworms; this family includes approximately 1,450 species11, 12. Brahmaeidae are a family of Bombycoidea11, 12. The Lasiocampidae are also a family of Bombycoidea, known as eggars, snout moths, or lappet moths. Over 2,000 species occur worldwide, and it is likely that not all have been named or studied13.

Table 1.

List of Bombycoidea species analysed in this paper with their respective GenBank accession numbers.

| Superfamily | Family | Species | Size (bp) | GBAN* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bombycoidea | Sphingidae | Ampelophaga rubiginosa | 15,282 | KT153024 |

| Bombycoidea | Bombycidae | Rondotia menciana | 15,636 | KT258908 |

| Bombycoidea | Bombycidae | Rondotia menciana | 15,301 | KC881286 |

| Bombycoidea | Bombycidae | Rondotia menciana | 15,364 | KJ647172 |

| Bombycoidea | Bombycidae | Andraca theae | 15,737 | KX365419 |

| Bombycoidea | Bombycidae | Bombyx mandarina | 15,928 | AB070263 |

| Bombycoidea | Bombycidae | Bombyx mori | 15,643 | AF149768 |

| Bombycoidea | Bombycidae | Bombyx huttoni | 15,638 | KP216766 |

| Bombycoidea | Saturniidae | Samia cynthia ricini | 15,384 | JN215366 |

| Bombycoidea | Saturniidae | Actias selene | 15,236 | JX186589 |

| Bombycoidea | Saturniidae | Antheraea pernyi | 15,566 | AY242996 |

| Bombycoidea | Saturniidae | Antheraea yamamai | 15,338 | EU726630 |

| Bombycoidea | Saturniidae | Eriogyna pyretorum | 15,327 | FJ685653 |

| Bombycoidea | Saturniidae | Saturnia boisduvalii | 15,360 | EF622227 |

| Bombycoidea | Saturniidae | Antheraea assama | 15,312 | KU301792 |

| Bombycoidea | Saturniidae | Samia cynthia cynthia | 15,345 | KC812618 |

| Bombycoidea | Saturniidae | Antheraea frithi | 15,338 | KJ740437 |

| Bombycoidea | Saturniidae | Attacus atlas | 15,282 | KF006326 |

| Bombycoidea | Saturniidae | Actias artemis aliena | 15,243 | KF927042 |

| Bombycoidea | Saturniidae | Samia canningi | 15,384 | KJ159909 |

| Bombycoidea | Lasiocampidae | Dendrolimus spectabilis | 15,411 | KM244678 |

| Bombycoidea | Lasiocampidae | Dendrolimus tabulaeformis | 15,411 | KJ913817 |

| Bombycoidea | Lasiocampidae | Dendrolimus punctatus | 15,411 | KJ913813 |

| Bombycoidea | Lasiocampidae | Apatelopteryx phenax | 15,552 | KJ508055 |

| Bombycoidea | Lasiocampidae | Trabala vishnou guttata | 15,281 | KU884483 |

| Bombycoidea | Lasiocampidae | Euthrix laeta | 15,368 | KU870700 |

| Bombycoidea | Sphingidae | Daphnis nerii | 15,247 | |

| Bombycoidea | Sphingidae | Agrius convolvuli | 15,349 | |

| Bombycoidea | Sphingidae | Manduca sexta | 15,516 | EU286785 |

| Bombycoidea | Sphingidae | Sphinx morio | 15,299 | KC470083 |

| Bombycoidea | Sphingidae | Notonagemia analis scribae | 15,303 | KU934302 |

| Bombycoidea | Brahmaeidae | Brahmaea hearseyi | 15,442 | KU884326 |

*GenBank accession number.

Here, we sequenced the complete mt genomes of two species, A. rubiginosa and R. menciana. We aimed to analyse the mt genomes of these two species and to investigate the phylogeny of Bombycoidea insects. We were particularly interested in the phylogenetic position of Sphingidae and Bombycidae based on the 32 Bombycoidea complete mt genomes available to date.

Materials and Methods

Specimen collection

The moths of A. rubiginosa and R. menciana were collected in Xuancheng, Anhui Province. Total DNA was isolated using the Genomic DNA Extraction Kit (SangonBiotech, China) according to manufacturer instructions. Extracted DNA was used to amplify the complete mt genomes by PCR.

PCR amplification and sequencing

For amplification of the entire mt genomes of A. rubiginosa and R. menciana, specific primers were designed based on mt genomes sequences obtained from other Lepidopteran insects14, 15 (Table 2). The complete mt genomes were obtained using a combination of conventional PCR and long PCR to amplify overlapping fragments spanning the complete mt genomes. All amplifications were performed on an Eppendorf Mastercycler and Mastercycler gradient in 50 µl reaction volumes with 5 µl of 10 × Taq Buffer (Mg2+) (Aidlab), 4 µl of dNTPs (2.5 mM, Aidlab), 2 µl of each primer (10 µM), 2 µl of DNA (~100 ng), 34.5 µl of ddH2O, and 0.5 µl of Red Taq DNA polymerase (5U, Aidlab). PCR was performed under the following conditions: 3 min at 94 °C, followed by 35 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 1–3 min at 54–60 °C (depending on primer combination), elongation at 72 °C for 30 s to 4 min (depending on the fragment length) and final extension at 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis (1% w/v) and purified using a DNA gel extraction kit (Transgene, China). The purified PCR products were ligated into the T-vector (SangonBiotech, China) and sequenced.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study.

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) | Annealing temperature | Region |

|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | GCTTTTGGGCTCATACCTCA | 56 °C | trnM-cox1 |

| R1 | GATGAAATACCTGCAAGATGAAG | ||

| F2 | TGGAGCAGGAACAGGATGAAC | 55 °C | cox1-trnK |

| R2 | GAGACCADTACTTGCTTTCAG | ||

| F3 | ATTTGTGGAGCTAATCATAG | 56 °C | cox2- cox3 |

| R3 | GGTCAGGGACTATAATCTAC | ||

| F4 | TCGACCTGGAACTTTAGC | 55 °C | atp6- nad5 |

| R4 | GCAGCTATAGCCGCTCCTACT | ||

| F5 | TAAAGCAGAAACAGGAGTAG | 54 °C | nad5 |

| R5 | ATTGCGATATTATTTCTTTTG | ||

| F6 | CCCCAGCAGTAACTAAAGTAGAAG | 54 °C | nad5-cob |

| R6 | GTTAAAGTGGCATTATCT | ||

| F7 | GGAGCTTCTACATGAGCTTTTGG | 56 °C | nad4-rrnL |

| R7 | GTTTGCGACCTCGATGTTG | ||

| F8 | GGTCCCTTACGAATTTGAATATATCCT | 60 °C | nad1-rrnS |

| R8 | AAACTAGGATTAGATACCCTATTAT | ||

| F9 | CTCTACTTTGTTACGACTTATT | 55 °C | rrnS-nad2 |

| R9 | TCTAGGCCAATTCAACAACC |

Sequence analysis

Annotation of sequences were performed using the blast tools in NCBI web site (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). The sequences were edited and assembled using EditSeq and SeqMan (DNAStar package, DNAStar Inc. Madison, WI, USA). The graphical maps of A. rubiginosa and R. menciana complete mt genomes were drawn using the online mitochondrial visualization tool mtviz (http://pacosy.informatik.uni-leipzig.de/mtviz). The nucleotide sequences of PCGs were translated with the invertebrate mt genome genetic code. Alignments of A. rubiginosa and R. menciana PCGs with various Bombycoidea mt genomes were performed using MAFFT16. Composition skewness was calculated according to the following formulas:

Nucleotide composition statistics and codon usage were computed using MEGA 5.017.

Phylogenetic analysis

Thirty complete Bombycoidea mt genomes were downloaded from GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/). In addition, mt genomes of Biston panterinaria and Phthonandria atrilineata were downloaded from GenBank and used as outgroup taxa. GenBank sequence information is shown in Table 1.

We estimated the taxonomic status of A. rubiginosa and R. menciana within Bombycoidea by constructing phylogenetic trees. Sequences from the PCGs of 34 mt genomes were combined. Two inference methods were used for analysis: Bayesian inference (BI) and Maximum likelihood (ML). BI was performed with MrBayes v 3.2.118. While ML was performed with raxmlGUI19. Nucleotide substitution model selection was done using the Akaike information criterion implemented in MrModeltest v 2.320. ProtTest version 1.421 was used to select the amino acid substitution model. The GTR + I + G model was the best for nucleotide data, and the MtREV + I + G + F model was the best for amino acids. ML analysis was performed on 1000 bootstrapped datasets. The Bayesian analysis ran as 4 simultaneous MCMC chains for 10,000,000 generations, sampled every 100 generations, with a burn-in of 5000 generations. Convergence was tested for the Bayesian analysis by ensuring that the average standard deviation of split frequencies was less than 0.01. Additionally, we tested for sufficient parameter sampling by ensuring an ESS of more than 200 using the software Tracer v1.622. The resulting phylogenetic trees were visualized in FigTree v1.4.223.

Results and Discussion

Genome structure, organization and composition

The complete sequences of A. rubiginosa and R. menciana, 15,282 bp and 15,636 bp in size, respectively, were determined and submitted to GenBank (Accession No. KT153024 and KT258908). These two mt genomes both contain 13 PCGs, two rRNA genes, 22 tRNA genes, and an A + T-rich region. Four of the 13 PCGs (ND5, ND4, ND4L, and ND1), 8 tRNAs (trnQ, trnC, trnY, trnF, trnH, trnP, trnL (CUN), and trnV) and two rRNAs (rrnL and rrnS) are coded with the minority-strand, while the remaining 23 genes are encoded by the majority-strand in A. rubiginosa and R. menciana (Fig. 1, Table 3). The length of the R. menciana mt genome (15,636 bp) is larger than A. rubiginosa (15,282 bp) and smaller than that of Bombyx mandarina (15,928 bp), B. mori (15,643 bp) and B. huttoni (15,638 bp), but it falls within the range (15,236–15,928 bp) of other known Bombycoidea mt genomes in our study (Table 1). The nucleotide composition of the A. rubiginosa mt genome is as follows (Table 4): A = 6,334 (41.4%), T = 6,126 (40.1%), G = 1,144 (7.5%), and C = 1,678 (11.0%). The nucleotide composition of the A. rubiginosa mt genome is A + T rich (81.5%) but is lower than that of R. menciana (82.2%). The AT skew24 is slightly positive and the GC skew is negative in these two mt genomes (Table 4), indicating an obvious bias towards the use of As and Cs. The order and orientation of genes in the A. rubiginosa and R. menciana mt genomes are identical to other bombicoid insects sequenced to date25, but differ from ancestral insects26. The placement of the trnM gene in the A. rubiginosa and R. menciana mt genome is trnM-trnI-trnQ, while in ancestral insects, it is trnI-trnQ-trnM (Fig. 2). Ghost moths exhibited the ancestral insect placement of the trnM gene cluster27. The hypothesis that the ancestral arrangement of the trnM gene cluster underwent rearrangement after Hepialoidea diverged from other Lepidopteran lineages was supported by our results in A. rubiginosa and R. menciana. The tRNA rearrangements are generally presumed to be a consequence of tandem duplication of partial mt genomes28–31, followed by random or non-random loss of the duplicated copies28, 32, 33.

Figure 1.

Circular map of the mt genomes of A. rubiginosa (A) and R. Menciana (B). tRNA-Ser1, tRNA-Ser2, tRNA-Leu1 and tRNA-Leu2 denote codons tRNA-Ser1 (AGN), tRNA-Ser2 (UCN), tRNA-Leu1 (CUN), and tRNA-Leu2 (UUR), respectively.

Table 3.

Summary of the mt genomes of A. rubiginosa and R. menciana.

| Gene | Direction | Location | Size | Anticodon | Start codon | Stop codon | Intergenic nucleotides |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| trnM | F | 1–68 | 68 | CAT | — | — | 0 |

| trnI | F | 69–132 | 64 | GAT | — | — | −3 |

| trnQ | R | 130–198 | 69 | TTG | — | — | 56 |

| nad2 | F | 255–1266 | 1012 | — | ATT | T | 0 |

| trnW | F | 1267–1334 | 68 | TCA | — | — | −8 |

| trnC | R | 1327–1391 | 65 | GCA | — | — | 0 |

| trnY | R | 1392–1456 | 65 | GTA | — | — | 6 |

| cox1 | F | 1463–2990 | 1528 | — | CGA | T | 0 |

| trnL2(UUR) | F | 2991–3058 | 68 | TAA | — | — | 0 |

| cox2 | F | 3059–3740 | 682 | — | ATG | T | 0 |

| trnK | F | 3741–3811 | 71 | CTT | — | — | 2 |

| trnD | F | 3814–3881 | 68 | GTC | — | — | 0 |

| atp8 | F | 3882–4043 | 162 | — | ATT | TAA | −7 |

| atp6 | F | 4037–4714 | 678 | — | ATG | TAA | 0 |

| cox3 | F | 4715–5506 | 792 | — | ATG | TAA | 2 |

| trnG | F | 5509–5574 | 66 | TCC | — | — | 0 |

| nad3 | F | 5575–5926 | 352 | — | ATT | T | 0 |

| trnA | F | 5927–5993 | 67 | TGC | — | — | 1 |

| trnR | F | 5995–6058 | 64 | TCG | — | — | 0 |

| trnN | F | 6059–6124 | 66 | GTT | — | — | 0 |

| trnS1(AGN) | F | 6125–6186 | 62 | GCT | — | — | 9 |

| trnE | F | 6196–6263 | 68 | TTC | — | — | −2 |

| trnF | R | 6262–6327 | 66 | GAA | — | — | 27 |

| nad5 | R | 6355–8076 | 1722 | — | ATT | A | 15 |

| trnH | R | 8092–8155 | 64 | GTG | — | — | 0 |

| nad4 | R | 8156–9490 | 1335 | — | ATG | TAA | 0 |

| nad4L | R | 9491–9781 | 291 | — | ATG | TAA | 4 |

| trnT | F | 9786–9851 | 66 | TGT | — | — | −1 |

| trnP | R | 9851–9916 | 66 | TGG | — | — | 6 |

| nad6 | F | 9923–10,453 | 531 | — | ATG | TAA | 6 |

| cob | F | 10,460–11,608 | 1149 | — | ATG | TAA | −1 |

| trnS2(UCN) | F | 11,608–11,672 | 65 | TGA | — | — | 21 |

| nad1 | R | 11,694–12,629 | 936 | — | ATG | TAA | 0 |

| trnL1(CUN) | R | 12,630–12,696 | 67 | TAG | — | — | 0 |

| rrnL | R | 12,697–14,040 | 1344 | — | — | — | 0 |

| trnV | R | 14,041–14,108 | 68 | TAC | — | — | 0 |

| rrnS | R | 14,109–14,883 | 775 | — | — | — | 0 |

| A + T-rich region | 14,884–15,282 | 399 | — | — | — | ||

| trnM | F | 1–68 | 68 | CAT | — | — | 0 |

| trnI | F | 69–132 | 64 | GAT | — | — | −3 |

| trnQ | R | 130–198 | 69 | TTG | — | — | 52 |

| nad2 | F | 251–1264 | 1014 | — | ATT | TAA | 7 |

| trnW | F | 1272–1338 | 67 | TCA | — | — | −8 |

| trnC | R | 1331–1394 | 64 | GCA | — | — | 0 |

| trnY | R | 1395–1459 | 65 | GTA | — | — | 9 |

| cox1 | F | 1469–2999 | 1531 | — | CGA | T | 0 |

| trnL2(UUR) | F | 3000–3066 | 67 | TAA | — | — | 0 |

| cox2 | F | 3067–3748 | 682 | — | ATG | T | 0 |

| trnK | F | 3749–3819 | 71 | CTT | — | — | −1 |

| trnD | F | 3819–3884 | 66 | GTC | — | — | 0 |

| atp8 | F | 3885–4046 | 162 | — | ATC | TAA | −7 |

| atp6 | F | 4040–4717 | 678 | — | ATG | TAA | 3 |

| cox3 | F | 4721–5509 | 789 | — | ATG | TAA | 2 |

| trnG | F | 5512–5577 | 66 | TCC | — | — | 0 |

| nad3 | F | 5575–5931 | 357 | — | ATA | TAA | 27 |

| trnA | F | 5959–6032 | 74 | TGC | — | — | 10 |

| trnR | F | 6043–6105 | 63 | TCG | — | — | 0 |

| trnN | F | 6106–6173 | 68 | GTT | — | — | 6 |

| trnS1(AGN) | F | 6180–6248 | 69 | GCT | — | — | 1 |

| trnE | F | 6250–6314 | 65 | TTC | — | — | 3 |

| trnF | R | 6318–6385 | 68 | GAA | — | — | 0 |

| nad5 | R | 6386–8124 | 1739 | — | ATT | TA | 0 |

| trnH | R | 8125–8190 | 66 | GTG | — | — | 10 |

| nad4 | R | 8201–9541 | 1341 | — | ATG | TAA | 5 |

| nad4L | R | 9547–9837 | 291 | — | ATG | TAA | 2 |

| trnT | F | 9840–9904 | 65 | TGT | — | — | 0 |

| trnP | R | 9905–9970 | 66 | TGG | — | — | 2 |

| nad6 | F | 9973–10,503 | 531 | — | ATG | TAA | 7 |

| cob | F | 10,511–11,665 | 1155 | — | ATG | TAA | 10 |

| trnS2(UCN) | F | 11,676–11,727 | 52 | TGA | — | — | 33 |

| nad1 | R | 11,761–12,699 | 939 | — | ATG | TAA | 1 |

| trnL1(CUN) | R | 12,701–12,770 | 70 | TAG | — | — | 0 |

| rrnL | R | 12,771–14,186 | 1416 | — | — | — | 0 |

| trnV | R | 14,187–14,252 | 66 | TAC | — | — | 0 |

| rrnS | R | 14,253–15,032 | 780 | — | — | — | 0 |

| A + T-rich region | 15,033–15,636 | 604 | — | — | — |

Table 4.

Composition and skewness in the A. rubiginosa and R. menciana mt genomes.

| A. rubiginosa | Size (bp) | A (bp) | tCT (bp) | G (bp) | C (bp) | A % | T % | G % | C % | AT % | AT skew | GC skew |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole genome | 15,282 | 6334 | 616126 | 1144 | 1678 | 41.4 | 40.1 | 7.5 | 11.0 | 81.5 | 0.017 | −0.189 |

| Protein-coding genes | 11,175 | 3894 | 5090 | 1135 | 1056 | 34.8 | 45.5 | 10.2 | 9.5 | 80.3 | −0.133 | 0.038 |

| tRNA genes | 1461 | 602 | 589 | 116 | 154 | 41.2 | 40.3 | 7.9 | 10.6 | 81.5 | 0.011 | −0.141 |

| rRNA genes | 2119 | 906 | 887 | 104 | 222 | 42.8 | 41.9 | 4.9 | 10.4 | 84.7 | 0.011 | −0.362 |

| A + T-rich region | 399 | 174 | 194 | 14 | 17 | 43.6 | 48.6 | 3.5 | 4.3 | 92.2 | −0.054 | −0.097 |

| Whole genome | 15,636 | 6561 | 6290 | 1122 | 1663 | 42.0 | 40.2 | 7.2 | 10.6 | 82.2 | 0.021 | −0.194 |

| Protein-coding genes | 11,205 | 3934 | 5107 | 1114 | 1050 | 35.1 | 45.6 | 9.9 | 9.4 | 80.7 | −0.130 | 0.030 |

| tRNA genes | 1460 | 606 | 588 | 115 | 151 | 41.5 | 40.3 | 7.9 | 10.3 | 81.8 | 0.015 | −0.135 |

| rRNA genes | 2196 | 959 | 927 | 100 | 210 | 43.7 | 42.2 | 4.5 | 9.6 | 85.9 | 0.017 | −0.355 |

| A + T-rich region | 604 | 281 | 287 | 18 | 18 | 46.5 | 47.5 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 94.0 | −0.011 | 0 |

Figure 2.

The mitochondrial gene order of ancestral insects and A. rubiginosa and R. menciana.

Protein-coding genes

Summaries of the genes that make up the mt genomes of A. rubiginosa and R. menciana are given in Table 3. Twelve of the thirteen PCGs use standard ATN start codons in A. rubiginosa and R. menciana, except for cox1, which is initiated by the CGA codon (arginine). The CGA codon is highly conserved across most insect groups14, 34. In A. rubiginosa, eight PCGs (atp8, atp6, cox3, nad4, nad4L, nad6, cob, and nad1) have the complete stop codon TAA, while the remaining five terminate with either T (nad2, cox1, cox2, and nad3) or A (nad5). In R. menciana, ten PCGs (nad2, atp8, atp6, cox3, nad3, nad4, nad4L, nad6, cob, and nad1) have the complete stop codon TAA, while the remaining three terminate with either T (cox1 and cox2) or TA (nad5). For A. rubiginosa, the average AT content of the 13 PCGs is 80.3%, and the overall AT and GC skews are –0.133 and 0.038, showing that T and G are more abundant than A and C. Similarly, the A + T composition of the 13 PCGs in the mt genome of R. menciana is 80.7%, while the AT and GC skews are –0.130 and 0.030, showing that T and G are more abundant than A and C (Table 4). Relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) values for the A. rubiginosa and R. menciana mt genomes are summarized in Table 5 and Fig. 3, which show that NNT and NNA are more frequent than NNG and NNC, indicating a strong A or T bias in the third codon position. The most common amino acids for A. rubiginosa and R. menciana mitochondrial proteins are Leu (UUR), Ile, and Phe (Fig. 4).

Table 5.

Codon number and RSCU in the A. rubiginosa and R. menciana mitochondrial PCGs.

| Codon | Count | RSCU | Codon | Count | RSCU | Codon | Count | RSCU | Codon | Count | RSCU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UUU(F) | 347 | 1.88 | UCU(S) | 91 | 2.35 | UAU(Y) | 184 | 1.86 | UGU(C) | 31 | 1.82 |

| UUC(F) | 23 | 0.12 | UCC(S) | 1 | 0.03 | UAC(Y) | 14 | 0.14 | UGC(C) | 3 | 0.18 |

| UUA(L) | 482 | 5.32 | UCA(S) | 103 | 2.66 | UAA(*) | 10 | 2 | UGA(W) | 91 | 1.94 |

| UUG(L) | 14 | 0.15 | UCG(S) | 0 | 0 | UAG(*) | 0 | 0 | UGG(W) | 3 | 0.06 |

| CUU(L) | 26 | 0.29 | CCU(P) | 63 | 1.98 | CAU(H) | 57 | 1.73 | CGU(R) | 13 | 1 |

| CUC(L) | 2 | 0.02 | CCC(P) | 12 | 0.38 | CAC(H) | 9 | 0.27 | CGC(R) | 0 | 0 |

| CUA(L) | 20 | 0.22 | CCA(P) | 52 | 1.64 | CAA(Q) | 63 | 2 | CGA(R) | 37 | 2.85 |

| CUG(L) | 0 | 0 | CCG(P) | 0 | 0 | CAG(Q) | 0 | 0 | CGG(R) | 2 | 0.15 |

| AUU(I) | 452 | 1.91 | ACU(T) | 83 | 2.26 | AAU(N) | 239 | 1.85 | AGU(S) | 22 | 0.57 |

| AUC(I) | 22 | 0.09 | ACC(T) | 6 | 0.16 | AAC(N) | 19 | 0.15 | AGC(S) | 0 | 0 |

| AUA(M) | 276 | 1.86 | ACA(T) | 56 | 1.52 | AAA(K) | 102 | 1.92 | AGA(S) | 92 | 2.37 |

| AUG(M) | 21 | 0.14 | ACG(T) | 2 | 0.05 | AAG(K) | 4 | 0.08 | AGG(S) | 1 | 0.03 |

| GUU(V) | 74 | 2.26 | GCU(A) | 75 | 2.59 | GAU(D) | 58 | 1.9 | GGU(G) | 62 | 1.29 |

| GUC(V) | 1 | 0.03 | GCC(A) | 0 | 0 | GAC(D) | 3 | 0.1 | GGC(G) | 0 | 0 |

| GUA(V) | 55 | 1.68 | GCA(A) | 40 | 1.38 | GAA(E) | 70 | 1.87 | GGA(G) | 111 | 2.31 |

| GUG(V) | 1 | 0.03 | GCG(A) | 1 | 0.03 | GAG(E) | 5 | 0.13 | GGG(G) | 19 | 0.4 |

| UUU(F) | 369 | 1.9 | UCU(S) | 94 | 2.39 | UAU(Y) | 178 | 1.87 | UGU(C) | 29 | 1.81 |

| UUC(F) | 20 | 0.1 | UCC(S) | 10 | 0.25 | UAC(Y) | 12 | 0.13 | UGC(C) | 3 | 0.19 |

| UUA(L) | 478 | 5.32 | UCA(S) | 97 | 2.47 | UAA(*) | 11 | 2 | UGA(W) | 90 | 1.94 |

| UUG(L) | 14 | 0.16 | UCG(S) | 0 | 0 | UAG(*) | 0 | 0 | UGG(W) | 3 | 0.06 |

| CUU(L) | 24 | 0.27 | CCU(P) | 60 | 1.98 | CAU(H) | 57 | 1.73 | CGU(R) | 14 | 1.06 |

| CUC(L) | 3 | 0.03 | CCC(P) | 10 | 0.33 | CAC(H) | 9 | 0.27 | CGC(R) | 0 | 0 |

| CUA(L) | 19 | 0.21 | CCA(P) | 48 | 1.59 | CAA(Q) | 60 | 2 | CGA(R) | 38 | 2.87 |

| CUG(L) | 1 | 0.01 | CCG(P) | 3 | 0.1 | CAG(Q) | 0 | 0 | CGG(R) | 1 | 0.08 |

| AUU(I) | 452 | 1.9 | ACU(T) | 67 | 1.91 | AAU(N) | 246 | 1.82 | AGU(S) | 30 | 0.76 |

| AUC(I) | 25 | 0.1 | ACC(T) | 6 | 0.17 | AAC(N) | 24 | 0.18 | AGC(S) | 1 | 0.03 |

| AUA(M) | 285 | 1.89 | ACA(T) | 67 | 1.91 | AAA(K) | 107 | 1.88 | AGA(S) | 82 | 2.09 |

| AUG(M) | 17 | 0.11 | ACG(T) | 0 | 0 | AAG(K) | 7 | 0.12 | AGG(S) | 0 | 0 |

| GUU(V) | 66 | 2.08 | GCU(A) | 65 | 2.39 | GAU(D) | 62 | 1.88 | GGU(G) | 52 | 1.09 |

| GUC(V) | 1 | 0.03 | GCC(A) | 3 | 0.11 | GAC(D) | 4 | 0.12 | GGC(G) | 1 | 0.02 |

| GUA(V) | 56 | 1.76 | GCA(A) | 39 | 1.43 | GAA(E) | 66 | 1.83 | GGA(G) | 126 | 2.65 |

| GUG(V) | 4 | 0.13 | GCG(A) | 2 | 0.07 | GAG(E) | 6 | 0.17 | GGG(G) | 11 | 0.23 |

Figure 3.

The relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) in the mt genomes of A. rubiginosa (A) and R. menciana (B).

Figure 4.

Amino acid composition in the mt genomes of A. rubiginosa (A) and R. menciana (B).

Transfer RNA and ribosomal RNA genes

A. rubiginosa and R. menciana both contain 22 tRNAs. Eight of these tRNAs (trnQ, trnC, trnY, trnF, trnH, trnP, trnL(CUN), and trnV) are coded with the minority-strand, while the remaining 14 tRNA genes are encoded by the majority-strand in A. rubiginosa and R. menciana (Table 3). The total length of the 22 tRNAs in the mt genome of A. rubiginosa is 1461 bp, and their A + T content is 81.5%. Similarly, the total length of the 22 tRNAs in the mt genome of R. menciana is 1460 bp and their A + T content is 81.8%. The AT skew is slightly positive and the GC skew is negative in the 22 tRNAs of A. rubiginosa and R. menciana (Table 4). The rrnL and rrnS genes of A. rubiginosa and R. menciana are located between trnL1(CUN) and trnV and between trnV and the A + T-rich region, respectively. The A + T content of the two rRNA genes is 84.7% in A. rubiginosa, which is lower than that of R. menciana (85.9%) (Table 4).

A + T-rich region

The A + T-rich regions of A. rubiginosa and R. menciana are located between rrnS and trnM and were 399 bp and 604 bp long, respectively. The A + T-rich regions contain 92.2% and 94.0% A + T contents in A. rubiginosa and R. menciana, respectively, which were the highest across the studied mt genomes (Table 4). The AT skew and GC skew of A. rubiginosa are −0.054 and −0.097, indicating an obvious bias towards the use of T and C. However, in the R. menciana A + T-rich region, AT skew is −0.011 and the number of G and C is the same, meaning that T is more abundant than A and that the usage of G and C is equal. Several conserved structures found in other bombicoid species mt genomes are also observed in the A + T-rich regions of A. rubiginosa and R. menciana. The conserved “ATAGA + poly T” motif is located downstream of the rrnS gene in the A + T-rich region of A. rubiginosa and R. menciana, which may represent the origin of minority or light strand replication31, and is conserved in lepidopteran mt genomes. Multiple tandem repeat elements are typically present in the A + T-rich region of most insects. Only one tandem repeat was found in the A. rubiginosa mt genome (Fig. S1). We identified two tandem repeats elements in the A + T-rich region of R. menciana (Fig. S2).

The mt genome of R. menciana has been previously sequenced, and two complete mt genomes of the species are available35, 36. However, in the present study, there was a difference of approximately 300 nt in the length of the mt genome of R. menciana compared to the two published sequences35, 36. The excess 300 nt of R. menciana in the present study mainly arose from the upper area of the A + T-rich region (Fig. S2). The A + T-rich regions of the R. menciana (Ankang Shaanxi) and R. menciana (Korea) mt genomes were identical. The length of tandem repeats of the A + T-rich region of R. menciana in this study was greater than the two published sequences.

Phylogenetic analysis

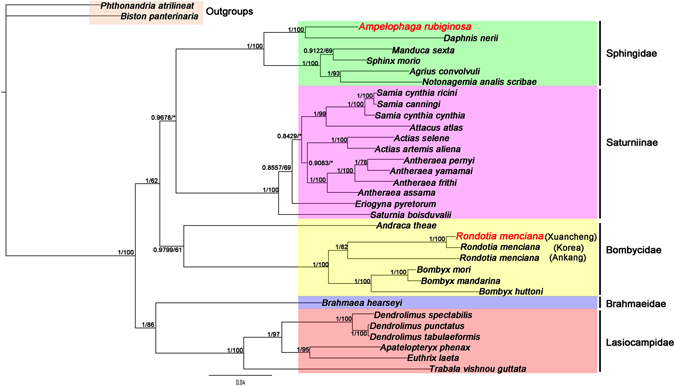

Phylogenetic analyses were based on sequences of 13 PCGs of 34 mt genomes using two methods (BI and ML) and alignments performed by MAFFT. B. panterinaria and P. atrilineata were used as outgroups. Thirty bombycoid species mt genomes that were downloaded from GenBank (plus A. rubiginosa and R. menciana) represent five families belonging to the Bombycoidea: Bombycidae, Lasiocampidae, Saturniidae, Brahmaeidae and Sphingidae. It is obvious that A. rubiginosa and Daphnis nerii 37 are clustered on one branch in the phylogenetic tree with high nodal support values. The analyses show that A. rubiginosa belongs in the Sphingidae family. The three phylogenetic trees consistently showed that R. menciana from Ankang was remarkably different from those of Korea and Xuancheng. The bombycid species were Andraca theae + ((R. menciana (Ankang)35 + (R. menciana (Xuancheng) + R. menciana (Korea)36)) + (B. huttoni + (B. mandarina 38 + B. mori))), indicating that R. menciana belongs in the Bombycidae family (Figs 5, 6 and 7).

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic tree derived for Bombycoidea using BI and ML analyses based on amino acid sequences and using MAFFT for alignment. Bayesian posterior probability (BPP) and bootstrap values (BP) of each node are shown as BPP/BP, with maxima of 1.00/100.

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic tree derived for Bombycoidea using BI analysis based on nucleotide sequences using MAFFT for alignment.

Figure 7.

Phylogenetic tree derived for Bombycoidea using BI and ML analyses based on 16S ribosomal RNA and 12S ribosomal RNA sequences of 33 species (there are no 16S ribosomal RNA and 12S ribosomal RNA sequences in the Apatelopteryx phenax (KJ508055)). Bayesian posterior probability (BPP) and bootstrap value (BP) of each node are shown as BPP/BP, with maxima of 1.00/100.

A problem remains with the phylogenetic relationships of families among the Bombycoidea in our study. The phylogenetic trees based on ML and BI analyses of amino acid sequences showed that the phylogenetic relationships were (Lasiocampidae + Brahmaeidae) + (Bombycidae + (Sphingidae + Saturniidae)) (Fig. 5), which is similar to some past studies10, 39. However, the phylogenetic tree based on BI analysis of nucleotide sequences showed that the phylogenetic relationships were (Lasiocampidae + Brahmaeidae) + (Sphingidae + (Bombycidae + Saturniidae)) (Fig. 6). The phylogenetic relationships of families in our study (Figs 5, 6 and 7) differ from the findings of other previous studies, where the families group as Lasiocampidae + (Saturniidae + (Bombycidae + Sphingidae))40. The reason for these differences may be the incorporation of complete mt genomes39. The relationships in the Bombycoidea remain unsettled. More mt genomes from Bombycoidea insects are required to resolve the positions of Bombycoidea in the future.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31672267 and 31640074), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20160444), the Natural Science Foundation of the Education Department of Jiangsu Province (15KJB240002, 12KJA180009, and 16KJA180008), the Jiangsu Provincial Key Laboratory of Coastal Wetland Bioresources and Environmental Protection (JLCBE14006), the Jiangsu Key Laboratory for Bioresources of Saline Soils (JKLBS2014013 and JKLBS2015004), and the Yancheng City Agricultural Science and Technology Guiding Project (YKN2014022).

Author Contributions

Q.N.L. and B.P.T. conceived and designed the experiments. Q.N.L., Z.Z.X., Y.L., X.Y.Z., and Y.W. performed the experiments. Q.N.L. and Z.Z.X. analysed the data. H.B.Z., D.Z.Z., C.L.Z. and B.P.T. contributed reagents and materials. Q.N.L. and Z.Z.X. wrote the paper. Z.Z.X., Q.N.L. and B.P.T. revised the paper.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-06930-5

Accession Numbers: The A. rubiginosa and R. Menciana mt genomes were submitted under the accession number KT153024 and KT258908 to NCBI, respectively.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Bo-Ping Tang, Email: boptang@163.com.

Qiu-Ning Liu, Email: liuqn@yctu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Wolstenholme DR. Animal mitochondrial DNA: Structure and evolution. Int. Rev. Cyt. 1992;141:173–216. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(08)62066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fauron CMR, Wolstenholme DR. Extensive diversity among Drosophila species with respective to nucleotide sequences within the adenine + thymine rich region of mitochondrial DNA molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;11:2439–2453. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.11.2439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang ST, et al. Characterization of the complete mitochondrial genome of the giant silkworm moth, Eriogyna pyretorum (Lepidoptera: Saturniidae) Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2009;5:351–365. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.5.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu QN, et al. A transfer RNA gene rearrangement in the lepidopteran mitochondrial genome. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017;489:149–154. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.05.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang DX, Szymura JM, Hewitt GM. Evolution and structural conservation of the control region of insect mitochondrial DNA. J. Mol. Evol. 1995;40:382–391. doi: 10.1007/BF00164024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cameron SL. Insect mitochondrial genomics: implications for evolution and phylogeny. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2014;59:95–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-011613-162007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun YX, et al. Characterization of the Complete Mitochondrial Genome of Leucoma salicis (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae) and Comparison with Other Lepidopteran Insects. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:39153. doi: 10.1038/srep39153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boore JL. Animal mitochondrial genomes. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 1999;27:1767–1780. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.8.1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christopher, O. Firefly encyclopedia of insects and spiders. Firefly Books Limited (2002).

- 10.Liu QN, Zhu BJ, Dai LS, Liu CL. The complete mitogenome of Bombyx mori strain Dazao (Lepidoptera: Bombycidae) and comparison with other lepidopteran insects. Genomics. 2013;101:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Nieukerken EJ, et al. Order Lepidoptera Linnaeus, 1758. Zootaxa. 2011;3148:212–221. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Common, I. F. B. Moths of Australia. Brill (1990).

- 13.Holloway, J. D. The moths of Borneo: superfamily Bombycoidea: families Lasiocampidae, Eupterotidae, Bombycidae, Brahmaeidae, Saturniidae, Sphingidae. Moths of Borneo (1987).

- 14.Liu QN, Zhu BJ, Dai LS, Wei GQ, Liu CL. The complete mitochondrial genome of the wild silkworm moth. Actias selene. Gene. 2012;505:291–299. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu QN, et al. Characterization of the complete mitochondrial genome of the Oriental armyworm, Mythimna separata (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) Eur. J. Entomol. 2015;112:399–408. doi: 10.14411/eje.2015.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katoh K, Misawa K, Kuma K, Miyata T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:3059–3066. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tamura K, et al. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood evolutionary distance and maximum parsimony. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ronquist F, et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012;61:539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silvestro D, Michalak I. raxmlGUI: a graphical front-end for RAxML. Org. Divers. Evol. 2012;12:335–337. doi: 10.1007/s13127-011-0056-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nylander, J. A. A. MrModeltest v 2. Program distributed by the author, vol. 2. Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University (2004).

- 21.Abascal F, Zardoya R, Posada D. ProtTest: selection of best-fit models of protein evolution. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:2104–2105. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rambaut, A., Suchard, M. A. & Drummond, A. J. Tracer v1.6. Available at: http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/tracer (Accessed: 16th June 2015).

- 23.Rambaut, A. FigTree v1. 4.2: Tree figure drawing tool. Available at: http://ac.uk/software/figtree/ (Accessed: 1th February 2015).

- 24.Perna NT, Kocher TD. Patterns of nucleotide composition at fourfold degenerate sites of animal mitochondrial genomes. J. Mol. Evol. 1995;41:353–358. doi: 10.1007/BF01215182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu QN, et al. The first complete mitochondrial genome for the subfamily Limacodidae and implications for the higher phylogeny of Lepidoptera. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:35878. doi: 10.1038/srep35878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boore JL, Lavrov DV, Brown WM. Gene translocation links insects and crustaceans. Nature. 1998;392:667. doi: 10.1038/33577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao YQ, Ma C, Chen JY, Yang DR. The complete mitochondrial genomes of two ghost moths, Thitarodes renzhiensis and Thitarodes yunnanensis: the ancestral gene arrangement in Lepidoptera. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:276. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Juhling F, et al. Improved systematic tRNA gene annotation allows new insights into the evolution of mitochondrial tRNA structures and into the mechanisms of mitochondrial genome rearrangements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:2833–2845. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shi W, Gong L, Wang SY. Tandem duplication and random loss for mitogenome rearrangement in Symphurus (Teleost: Pleuronectiformes) BMC Genomics. 2015;16:355. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1581-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Negrisolo E, Minelli A, Valle G. Extensive gene order rearrangement in the mitochondrial genome of the centipede Scutigera coleoptrata. J. Mol. Evol. 2004;58:413–423. doi: 10.1007/s00239-003-2563-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taanman JW. The mitochondrial genome: structure, transcription, translation and replication. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1410:103–123. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2728(98)00161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stanton DJ, Daehler LL, Moritz CC, Brown WM. Sequences with the potential to form stem-and-loop structures are associated with coding-region duplications in animal mitochondrial DNA. Genetics. 1994;137:233–241. doi: 10.1093/genetics/137.1.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rawlings TA, Collins TM, Bieler R. Changing identities: tRNA duplication and remolding within animal mitochondrial genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:15700–15705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2535036100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cameron SL, Whiting MF. The complete mitochondrial genome of the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta,(Insecta: Lepidoptera: Sphingidae), and an examination of mitochondrial gene variability within butterflies and moths. Gene. 2008;408:112–123. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kong WQ, Yang JH. The complete mitochondrial genome of Rondotia menciana (Lepidoptera: Bombycidae) J. Insect. Sci. 2015;15:48. doi: 10.1093/jisesa/iev032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim MJ, Jun J, Kim I. Complete mitochondrial genome of the mulberry white caterpillar Rondotia menciana (Lepidoptera: Bombycidae). Mitochondrial. DNA. 2016;27:731–733. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2014.913163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moore A, Miller RH. Daphnis nerii (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae), a new pest of oleander on Guam, including notes on plant hosts and egg parasitism. Pro. Hawaii. Entomol. Soc. 2008;40:67–70. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pan MH, et al. Characterization of mitochondrial genome of Chinese wild mulberry silkworm, Bomyx mandarina (Lepidoptera: Bombycidae) Sci. China Ser. C. 2008;51:693–701. doi: 10.1007/s11427-008-0097-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gu, X. S., Ma, L., Wang, X. & Huang, G. H. Analysis on the complete mitochondrial genome of Andraca theae (Lepidoptera: Bombycoidea). J. Insect. Sci. 16 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Timmermans MJTN, Lees DC, Simonsen TJ. Towards a mitogenomic phylogeny of Lepidoptera. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2014;79:169–178. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2014.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.