Abstract

Cadmium (Cd2+) is a known carcinogen that inactivates the DNA mismatch repair (MMR) pathway. In this study, we have tested the effect of Cd2+ exposure on the enzymatic activity of the mismatch binding complex MSH2–MSH6. Our results indicate that Cd2+ is highly inhibitory to the ATP binding and hydrolysis activities of MSH2–MSH6, and less inhibitory to its DNA mismatch binding activity. The inhibition of the ATPase activity appears to be dose and exposure time dependent. However, the inhibition of the ATPase activity by Cd2+ is prevented by cysteine and histidine, suggesting that these residues are essential for the ATPase activity and are targeted by Cd2+. A comparison of the mechanism of inhibition with N-ethyl maleimide, a sulfhydryl group inhibitor, indicates that this inhibition does not occur through direct inactivation of sulfhydryl groups. Zinc (Zn2+) does not overcome the direct inhibitory effect of Cd2+ on the MSH2–MSH6 ATPase activity in vitro. However, the increase in the mutator phenotype of yeast cells exposed to Cd2+ was prevented by excess Zn2+, probably by blocking the entry of Cd2+ into the cell. We conclude that the inhibition of MMR by Cd2+ is through the inactivation of the ATPase activity of the MSH2–MSH6 heterodimer, resulting in a dominant negative effect and causing a mutator phenotype.

INTRODUCTION

Mispaired bases result from incorporation errors during DNA biosynthesis that have escaped the proofreading activity of DNA polymerases as well as from the formation of heteroduplex DNA during recombination of divergent sequences. DNA mismatch repair (MMR) plays a major role in the recognition and correction of the mispaired bases, increasing replication fidelity and maintaining genome integrity. Defects in MMR are the underlying cause of a cancer susceptibility syndrome called HNPCC and account for 20% of sporadic cancers (1).

MMR is a complex reaction that involves multiple proteins, which recognize the mismatch, excise the DNA containing the error and resynthesize the correct DNA sequence. In eukaryotes, six functional MMR genes have been identified, MSH2, MSH3 and MSH6, which are homologs of MutS in Escherichia coli, while MLH1, MLH3 and PMS2 (PMS1 in yeast) are homologous to bacterial MutL (2–4). These genes are involved in the recognition of the mismatch, a critical step in the pathway, as illustrated by the fact that defects in these genes account for two-thirds of HNPCC cases. The initial recognition of mispairs is carried out by two protein complexes: the MSH2–MSH6 heterodimer, also known as MutSα, which recognizes base–base mismatches and frameshift mispairs (±1 bp), while the MSH2–MSH3 heterodimer, also known as MutSβ, recognizes frameshifts and larger insertion deletion mispairs (2–4 bp). The MutL homologs MLH1, PMS2 (PMS1 in yeast) and MLH3 form heterodimers MLH1–PMS1 and MLH1–MLH3, which participate in downstream events subsequent to the recognition of mismatches by the MSH complexes. Because of their requirement in the repair of both types of mispairs, MSH2 and MLH1 are regarded as the key factors in MMR as defects in the genes encoding these proteins result in a complete loss of repair.

ATP binding and hydrolysis by the dimeric MSH protein complexes is a critical aspect of MMR and is believed to modulate the interactions of MSH2–MSH6 and MSH2–MSH3with the mismatched DNA and other downstream factors (5–7). Several models have been proposed regarding the role of ATP in the recognition of mismatches by the MSH protein complexes, most of which agree on the basic principle of an ATP-dependent movement of the MSH heterodimers along the mismatched DNA following mismatch recognition. Thus, the presence of ATP reduces the steady-state affinity of MutSα for mismatched DNA (8). Opinions have differed regarding the fate of the ATP molecule. Some authors have suggested that hydrolysis of the ATP molecule and the energy generated thereby is necessary for the translocation of MSH proteins (6,9), while others have suggested that ATP binding alone can do the same (10,11). Formation of higher-order structures of the MSH2–MSH6 dimer with proteins, such as MLH1–PMS1 and PCNA, in the presence of ATP and mismatched DNA has also been reported previously (11–13).

Because of the essential role of ATP in MMR, it is likely that defects in ATP binding and hydrolysis severely affect the pathway. Mutations in the ATP-binding site of MSH2–MSH6 result in dominant negative alleles that exhibit a strong mutator phenotype (14,15). Cadmium (Cd2+) was shown recently to impair this essential DNA repair pathway in yeast, as well as in human cells in vivo (16).

Cd2+ is a ubiquitous metal with no known biological function, to which humans are exposed mainly through occupation, environmental contamination and from cigarette smoke (17). The deleterious effects of Cd2+ reported to date include generation of reactive oxygen species, inhibition of DNA repair, depletion of glutathione, alteration of apoptosis and enhanced peripheral arterial disease (18,19). Cd2+ has also been reported to have a high affinity for protein sulfhydryl groups, can compete with and replace Zn2+ in proteins, and can bind to DNA at random, causing single-strand DNA breaks (20,21).

In light of the reported inhibitory effect of Cd2+ on the DNA MMR machinery, we took a biochemical approach to further define the role of Cd2+ on MMR inhibition. Our results described here demonstrate the direct effects of Cd2+ on the MSH2–MSH6 dimer. We observed inhibition of ATP binding, concomitant with inhibition of the ATPase activity, as well as inhibition of the mispaired DNA-binding activity of MSH2–MSH6 in the presence of Cd2+, with the inhibition of the ATPase activity being significantly more pronounced. This inhibitory effect was also observed to be dose and exposure time dependent. In addition, a comparison of the inhibitory effect of Cd2+ on the ATPase activity of MSH2–MSH6 with N-ethyl maleimide (NEM), a sulfhydryl group inactivating compound, indicated that their methods of inhibition are different. However, Cd2+ was seen to bind to cysteine, a sulfur containing amino acid. Zn2+, a member of the same group in the periodic table as Cd2+, and a known antagonist of the mutagenic effects of Cd2+ (18,22), enhanced the inhibitory effect of Cd2+ in vitro. However, Zn2+ reduced the appearance of an increased mutator phenotype in yeast cells exposed to Cd2+. We propose a mechanism of inhibition whereby Cd2+ allows MSH2–MSH6 to bind to a mispair but prevents ATP hydrolysis, effectively abrogating the pathway at this stage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Purification of MSH2–MSH6

Saccharomyces cerevisiae MSH2–MSH6 was purified by chromatography on PBE94, single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) cellulose and Q Sepharose as described previously (23). Purity was estimated to be at least 90% by Coomassie-stained gels.

ATPase assay

The measurement of hydrolysis of [γ-32P]ATP into ADP and Pi by the MSH2–MSH6 was carried out as described previously (24). Briefly, the reaction was carried out in Buffer A containing 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 5.7 μg ml−1 activated calf thymus DNA and 2 mM [γ-32P]ATP. MSH2–MSH6 was pre-incubated with Cd2+ at 4°C for 10 min, mixed with the reaction buffer and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Aliquots (1 μl) of each reaction were spotted onto a polyethyleneamide-TLC plate (Sigma). ATP and Pi were separated by chromatography in 1 M formic acid and 0.5 M LiCl. Products were analyzed in a PhosphorImager and quantitated using the ImageQuant software. One unit of ATPase activity was defined as the amount of protein that hydrolyzed 1 pmol of ATP to ADP and Pi under the above mentioned conditions.

To assay for the inhibition of MSH2–MSH6 ATPase activity by Cd2+ in the presence of Zn2+, MSH2–MSH6 (5 μg) was pre-incubated with 50 μM Cd2+, 50 μM Zn2+ and a combination of both in Buffer B (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl and 0.5 mM EDTA) in a total volume of 100 μl for 10 min. To remove excess metal ions, the protein–metal mixtures were dialyzed against 500 ml Buffer B for 3 h with one change of buffer. The protein contents of the dialyzed mixtures were recovered and quantified by Bradford (Bio-Rad). MSH2–MSH6–Cd2+ complex (40 nM) was pre-incubated with 50 μM Zn2+. In addition, undialyzed MSH2–MSH6 protein (40 nM) was pre-incubated with 50 μM Zn2+, 50 μM Cd2+ and a combination of both. The dialyzed and undialyzed metal-treated samples were then incubated with Buffer A at 37°C for 30 min and spotted on a TLC plate. Chromatography was carried out as described above.

To test the effect of Cd2+ on sulfhydryl groups, the inhibition of MSH2–MSH6 ATPase activity was compared with that caused by NEM, a sulfhydryl alkylating agent. MSH2–MSH6 (5 μg) was pre-incubated with Cd2+ (0.5 mM) in Buffer B at 4°C for 10 min as described above. To remove excess Cd2+, the protein was then dialyzed against 500 ml Buffer B for 3 h with one change of buffer. The protein contents of the dialyzed mixtures were measured. The dialyzed Cd2+-treated MSH2–MSH6 protein (40 nM) was then pre-incubated with 5 mM NEM. In addition, 40 nM undialyzed MSH2–MSH6 protein was pre-incubated with 0.5 mM Cd2+, 5 mM NEM and a combination of both at 4°C for 10 min. The reaction mixtures were then incubated at 37°C for 30 min with the Buffer A, spotted on a TLC plate and analyzed as described above.

To determine whether reducing agents containing sulfhydryl groups could reverse the inhibitory effect of Cd2+ on the ATPase activity, MSH2–MSH6 protein (160 nM) was pre-incubated with excess of either Cd2+ (0.5 mM) or NEM (5 mM) at 4°C for 30 min, after which 2 mM DTT was added and the mixture was further incubated for 30 min. In addition, to test the capacity of DTT to prevent sulfhydryl group inhibition, MSH2–MSH6 was pre-incubated first with 2 mM DTT for 30 min, after which either Cd2+ (0.5 mM) or NEM (5 mM) was added and the mixture was incubated for an additional 30 min. As a control, MSH2–MSH6 was pre-incubated with either Cd2+ (0.5 mM) or NEM (5 mM) for 30 min. The reaction mixtures were then incubated with Buffer A at 37°C for 30 min and spotted on a TLC plate and assayed as described above.

The effect of different amino acids on Cd2+-induced inhibition of MSH2–MSH6 was performed as follows. Stock solution of amino acids (0.1 M) was made in water, and the pH was the adjusted to 7.0. Cysteine is oxidized to cystine at neutral pH and the latter has a very low solubility in water. Therefore, the pH of the cysteine solution was kept at pH 6.0. Tryptophan was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as its solubility in water was very low. DMSO is inhibitory toward the ATPase activity of MSH2–MSH6, so a control reaction in the absence of Cd2+ was carried out. Tyrosine could not be dissolved in water, DMSO or ethanol and was not tested. Cd2+ (0.5 mM) was pre-incubated with 10 mM amino acid for 30 min at 4°C and then with MSH2–MSH6 (160 nM) at 4°C for 10 min. This mixture was then incubated with Buffer A at 37°C for 30 min and spotted on TLC plates as described above.

ATP binding to MSH2–MSH6

The ATP-binding assay was carried out with a Hoefer 25 mm filtration apparatus, pre-cooled to 4°C (25). Nitrocellulose membranes (25 mm) (Whatman) were briefly (30 s) soaked in 0.4 M KOH, extensively rinsed with distilled water and then equilibrated with Buffer C (25 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.6, 100 mM NaCl and 10% v/v glycerol) at 4°C. MgCl2 was left out of the buffer mixture to ensure ATP binding and not hydrolysis. MSH2–MSH6 (100 nM) was pre-incubated with 0–0.5 mM Cd2+ at 4°C for 10 min in a total volume of 250 μl in Buffer C. An aliquot (10 μl) of the mixture was taken out and incubated with 2 mM [γ32P]ATP in Buffer A at 37°C for 30 min to assay for ATP hydrolysis activity as described above. The remaining mixture was further incubated with 1 μM [α32P]ATP for 10 min. Control reactions in the absence of Cd2+ and MSH2–MSH6 were also carried out. The binding mixture was then applied to the equilibrated membranes, filtered under vacuum and washed extensively (20 ml) with Buffer C. The filter membranes were dried at room temperature and radioactivity was quantitated in a liquid scintillation counter.

Yeast mutator assays

The lys2-10A reversion assay was used to assay mutator phenotype in yeast. Individual colonies of the strain RDKY3590 (a gift from Dr R. Kolodner; Genotype: a, ura3-52, leu2Δ1, trp1Δ63, hom3-10 and lys210A) was grown in synthetic complete medium (3 ml) supplemented with 2% glucose in presence of Cd2+ (1 μM) or Zn2+ (0–1 mM) or a combination of both. The cells were grown to saturation overnight with shaking at 30°C, washed twice with sterile water and resuspended in 1 ml sterile water. Dilutions were plated on YPD to quantify survival and on medium lacking lysine, to determine mutation frequency. The appearance of revertant colonies was an indication of a mutator phenotype. Mutation rates were determined by fluctuation analysis using at least five independent colonies per experiment (26). Each fluctuation test was repeated at least three times.

Duplex DNA substrates

Substrates for MMR assays were prepared by annealing 200 pmol each of oligonucleotides (Invitrogen) 5′-ATTTCCTTCAGCAGATAGGAACCATACTGATTCACAT-3′ (HFRO 1107), 5′-ATGTGAATCAGTATGGTTTCTATCTGCTGAAGGAAAT-3′ (HFRO 1108) and 5′-ATGTGAATCAGTGTTCCTATCTGCTGAAGGAAAT-3′ (HFRO 1109). HFRO 1108 and HFRO 1109 were annealed to HFRO 1107, yielding a G:T heteroduplex and a G:C homoduplex, respectively, by heating at 95°C for 5 min in 100 μl annealing buffer (0.5 M NaCl, 10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA) and slow cooling to 25°C over 3 h. To remove ssDNA, electrophoresis of the DNA duplex was carried out in a 12% polyacrylamide gel in TBE buffer (45 mM Tris-borate, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) at 150 V for 1 h under non-denaturing conditions. The band containing the double-stranded DNA was excised from the gel and DNA was extracted by phenol–chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. The purified oligonucleotide (20 pmol) was 5′ end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP (Amersham) by incubating with T4 polynucleotide kinase (NEB) at 37°C for 30 min in a reaction volume of 50 μl. Unincorporated [γ-32P]ATP was removed by purification in a G-25-Sephadex column (Roche). To test for the removal of ssDNA, aliquots of the duplex DNA were resolved in a 4.5% polyacrylamide gel under non-denaturing conditions.

Gel mobility shift assay of DNA binding

The purified [γ-32P]ATP labeled duplex DNA (G:T and G:C) was used as substrates for this assay. MSH2–MSH6 (80 nM) was pre-incubated with 0–0.5 mM Cd2+ at 4°C for 10 min and then incubated with 100 fmol G:T or G:C substrate in a Buffer D (20 mM HEPES-KOH, 5 mM MgCl2, 50 μg ml−1 BSA and 50 mM NaCl) in a total volume of 20 μl at 4°C for 15 min. The reaction was stopped with 4 μl of stop mixture (20% Ficoll and 0.75% bromophenol blue). Gel electrophoresis of 12 μl of the mixture was carried out under non-denaturing conditions in a 4.5% polyacrylamide gel (60:1 bisacrylamide) containing 5% glycerol in TBE buffer (45 mM Tris-borate, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) at 10 V/cm at 4°C. Gels were dried and exposed on Kodak BioMax film. Analysis using a PhosphorImager and the ImageQuant software was carried out.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis and graphing was performed using the GraphPad Prism 4 software package. Specific analysis for each experiment is indicated in each Figure legend. In most cases, the mean of at least three experiments is plotted together with the standard deviation. Linear regression was used for best curve fitting when necessary and is indicated.

RESULTS

Effect of Cd2+ on the ATPase and DNA-binding activities of MSH2–MSH6

Cd2+ exposure resulted in a strong mutator phenotype in yeast cells, as determined with frameshift mutation reporters (homonucleotide runs in the LYS2 gene that revert by −1 frameshifts), indicating that it reduces the MMR capacity (16). The initial mismatched DNA recognition and binding by the MSH proteins are crucial steps of the MMR pathway. In addition, ATP binding to the MSH proteins and hydrolysis are key control points (27). Therefore, we hypothesized that at a biochemical level, Cd2+ may have an effect on these two very important initial steps of the pathway.

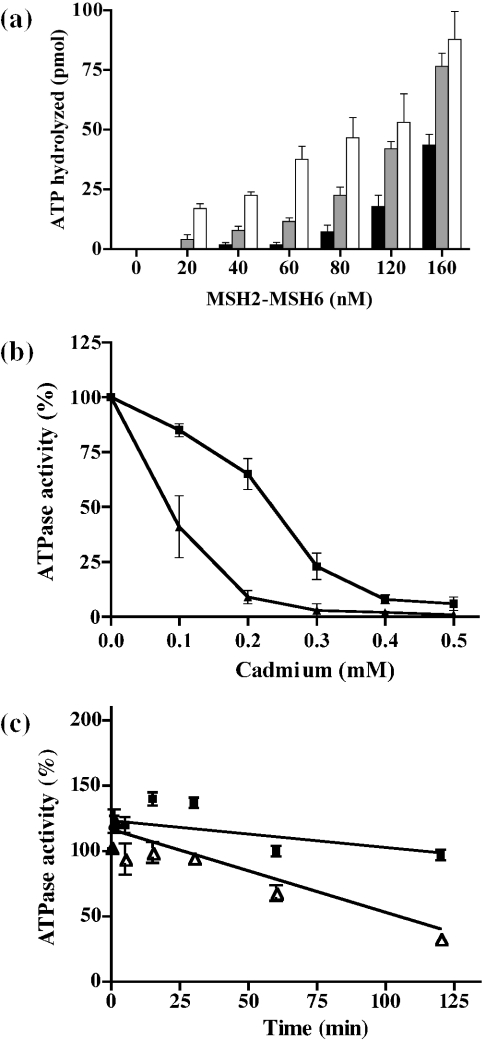

The ATP hydrolytic activity of increasing amounts of purified MSH2–MSH6 protein (0–160 nM) was tested in the presence of 100 μM Cd2+ (Figure 1a, gray bars) as described in Materials and Methods. A parallel reaction was carried out where MSH2–MSH6 (0–160 nM) was pre-incubated with Cd2+ for 10 min, before assaying for ATPase activity (Figure 1a, black bars). A control reaction of the ATP hydrolysis by MSH2–MSH6 (0–160 nM) in the absence of Cd2+ was also carried out (Figure 1a, white bars). The results indicate that Cd2+ severely inhibited the ATPase activity of MSH2–MSH6 at different levels of the protein (Figure 1a). In addition, pre-incubation with Cd2+ greatly enhanced the inhibitory effect, e.g. at 60 nM of MSH2–MSH6, Cd2+ pre-incubation resulted in only 6% (2.3 pmol ATP hydrolyzed) of the activity remaining, as opposed to 34% (13 pmol) of activity remaining when no pre-incubation was performed.

Figure 1.

Effect of cadmium on the ATPase activity of MSH2–MSH6. (a) Effect of 100 μM Cd2+ on increasing concentrations (0–160 nM) of MSH2–MSH6. Pre-incubation of Cd2+ with MSH2–MSH6 (black bars) at 4°C for 10 min followed by incubation with the reaction mixture containing ATP at 37°C for 30 min. Direct incubation of MSH2–MSH6 (gray bars) with Cd2+ and ATP in reaction mixture at 37°C for 30 min without any pre-incubation. ATPase activity of MSH2–MSH6 in the absence of Cd2+ (white bars). Each bar corresponds to the average of three experiments. Standard deviation is indicated at the top of each bar. (b) Effect of increasing concentrations of Cd2+ (0–0.5 mM) on 160 nM (closed squares) and 80 nM (closed triangles) of MSH2–MSH6. Pre-incubation of MSH2–MSH6 with Cd2+ at 4°C for 10 min was carried out. The average of three experiments for each concentration of Cd2+ is presented for MSH2–MSH6 at 160 nM and the average of four experiments for MSH2–MSH6 at 80 nM. Standard deviation is included. The curves were not fitted. (c) Time-course study over 120 min pre-incubation of the ATPase activity of MSH2–MSH6 (160 nM) in the presence (closed squares) and the absence of Cd2+ (open triangles). The average of three experiments for each time point is presented. Standard deviation is included. Curves were fitted by linear regression analysis.

To assay for the effect of increasing Cd2+ concentration on a fixed amount of MSH2–MSH6, concentrations of 0–0.5 mM Cd2+ were pre-incubated with 80 and 160 nM MSH2–MSH6 and assayed for ATPase activity as described above. The results (Figure 1b) indicated that the Cd2+-mediated inhibition of MSH2–MSH6 is dose dependent. At lower concentrations (Figure 1b, closed triangles), MSH2–MSH6 is significantly more sensitive to Cd2+ inhibition with 50% inhibition obtained with a Cd2+ concentration of 87 μM versus 240 μM for the higher concentration (Figure 1b, closed squares) of MSH2–MSH6 tested. At higher concentrations of Cd2+, the ATPase activity was almost completely abolished. At the lower concentration of MSH2–MSH6 used (Figure 1b, closed triangles), only 3% of the activity remained at 200 μM of Cd2+, while 8% activity remained at 500 μM for higher concentrations of MSH2–MSH6 (Figure 1b, closed squares).

A time-course study of the inhibition of Cd2+ (100 μM) with MSH2–MSH6 (160 nM) conducted at various time points over 120 min pre-incubation indicated that the inhibition is time dependent (Figure 1c). After 120 min pre-incubation with Cd2+ (Figure 1c, open triangles), MSH2–MSH6 displayed only 30% of the activity observed with 1 min pre-incubation.

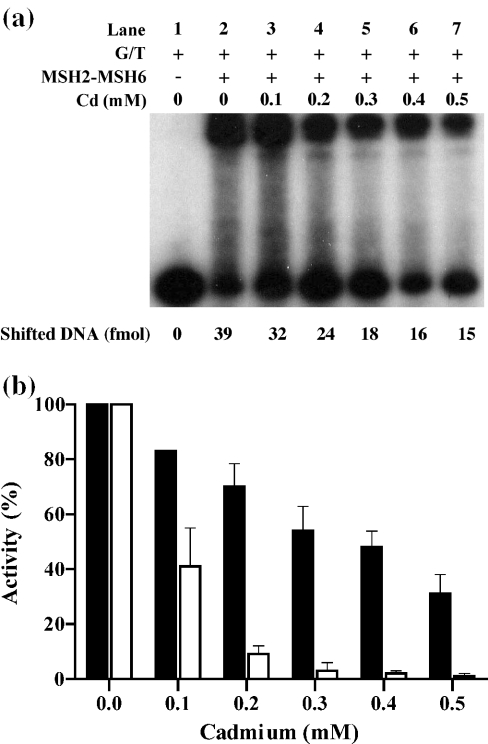

MSH2–MSH6 binds to DNA containing mismatches (23). To determine the effect of Cd2+ on the mismatched DNA-binding activity, MSH2–MSH6 was pre-incubated with 0.1–0.5 mM Cd2+ and aliquots were taken and assayed for DNA binding by gel mobility shift assay. DNA with mispairs (G:T) or fully paired (G:C) were used as substrates. Cd2+ inhibited the mismatched DNA-binding activity of MSH2–MSH6 (Figure 2a) in a dose-dependent manner. At the conditions tested, the binding of MSH2–MSH6 to the G:C substrate was negligible and was not significantly affected by Cd2+ treatment (data not shown). A comparison of the effect of 0–0.5 mM Cd2+ on the ATPase and DNA-binding activity of MSH2–MSH6 was carried out (Figure 2b). The data indicate that while Cd2+ causes a reduction in the mismatched DNA-binding capacity of MSH2–MSH6 (Figure 2b, black bars), it has a significantly more pronounced inhibitory effect on the ATPase activity of MSH2–MSH6 (Figure 2b, white bars). At concentrations of Cd2+ of 200 μM, 70% of the DNA-binding activity of MSH2–MSH6 remained, compared with only 8% of the ATPase activity, a 9-fold difference. Similar effect was observed when higher concentrations of Cd2+ were used (Figure 2b). As a control, the DNA-binding capacity of the ssDNA-binding protein, replication protein A, was tested and found to not be inhibited by Cd2+ (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Effect of cadmium on the DNA-binding activity of MSH2–MSH6. (a) MSH2–MSH6 was pre-incubated with Cd2+ at 4°C for 10 min, mixed with reaction mixture containing labeled G/T mispaired DNA and further incubated at 4°C for 15 min in 20 μl final volume. Gel was run with 10 μl of the mixture, and autoradiographed. Quantitation was carried out with a phosphorImager. (b) Comparison of the ATPase activity (white bars) and DNA mobility shift activity (black bars) of MSH2–MSH6 (80 nM) in the presence of 0–0.5 mM Cd2+. Activity is presented as a percentage of the activity of MSH2–MSH6 in the absence of Cd2+ taken as 100%. The average of three experiments for each concentration of Cd2+ is presented. Bars also include standard deviation.

Effect of Cd2+ on ATP-binding activity of MSH2–MSH6

To assay the effect of Cd2+ on the ATP-binding activity of MSH2–MSH6, a nucleotide filter binding assay was carried out. MSH2–MSH6 (100 nM) was incubated with 1 μM [α32P]ATP in the presence or absence of Cd2+ and filtered through nitrocellulose membrane as described in Materials and Methods. ATP binding to MSH2–MSH6 resulted in retention of radioactive signal on the membrane, which was measured in a scintillation counter. To compare the ATP-binding activity (Figure 3, white bars) of MSH2–MSH6 with its ATP hydrolysis activity (Figure 3, black bars) in the presence of Cd2+, an aliquot of the protein was simultaneously assayed for hydrolysis activity. The data indicate that the MSH2–MSH6 ATP-binding activity was inhibited in the presence of Cd2+ (Figure 3). The ATP-binding activity of MSH2–MSH6 was as sensitive as the hydrolysis activity to Cd2+ at every concentration. These results are consistent with a mechanism of inhibition of the MSH2–MSH6 ATPase activity as a consequence of reduced ATP binding.

Figure 3.

Effect of cadmium on the ATP hydrolysis and ATP-binding activities of MSH2–MSH6. MSH2–MSH6 was pre-incubated with Cd2+ (0–0.5 mM) at 4°C for 10 min. Aliquots were withdrawn and assayed for ATP hydrolysis (black bars) and ATP binding (white bars) as described in Materials and Methods. Results are expressed as a percentage of the activity of MSH2–MSH6 in the absence of Cd2+. For ATP hydrolysis 100% corresponds to 200 pmol ATP hydrolyzed, while for ATP binding, 100% of the activity corresponds to 2 pmol ATP bound. The average of three experiments for each concentration of Cd2+ is presented. Standard deviation is included.

Effect of Zn2+ on the Cd2+-induced mutator phenotype of yeast

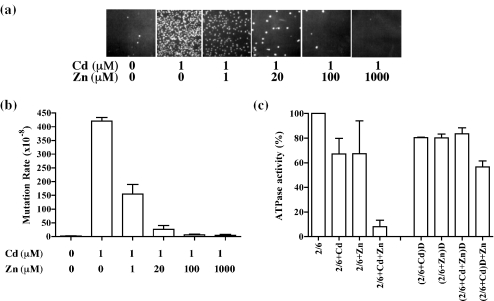

Yeast cells show a strong mutator phenotype after exposure to Cd2+ (16). To test the effect of Zn2+ on the Cd2+-induced mutator phenotype, the mutation rate in the presence of Cd2+ (1 μM) and Zn2+ (0–1000 μM) was determined using a yeast strain carrying the lys2-10A allele as a reporter for mutation accumulation. The results (Figure 4a and b) indicate that 1 μM Cd2+ is highly mutagenic to yeast, increasing the mutation rate to 4.2 × 10−6, a 221-fold effect compared with non-treated cells (background rate is 1.9 × 10−8). This inhibition is comparable with that observed in msh2 (9 × 10−6) and mlh1 (1 × 10−5) strains (data not shown). The presence of Zn2+ causes a dose-dependent decrease in the mutator phenotype of the lys2-10A cells. At a concentration of Zn2+ of 1 μM, equal to that of Cd2+, the mutator phenotype was reduced to 43% (rate of 1.8 × 10−6) to that observed with Cd2+ alone. At 1000-fold higher Zn2+ concentration than Cd2+, the appearance of a mutator phenotype was completely prevented yielding a mutation rate of 3.9 × 10−8, only 2-fold higher than untreated cells (Figure 4b). Cell viability did not considerably change at the concentration of Cd2+ used. A determination of the toxic concentrations of Cd2+ resulted in survival of 100% at 0 μM, 113% at 1 μM, 82% at 10 μM and 18% at 100 μM. These data are the average of three experiments, and the standard deviation range was no more than 20% at each concentration. This result reinforces the fact that at the concentration of Cd2+ used (1 μM), we are scoring for cadmium-induced mutagenesis and not toxicity. Similarly, the concentrations of Zn2+ utilized in our experiments did not greatly reduce the viability of the cells. Survival results of three independent experiments were 100% at 0 mM, 97% at 0.1 mM, 78% at 1 mM and 6.4% at 10 mM Zn2+. Because mutation rates were determined by fluctuation analysis using the method of Lea and Coulson (26), the small reduction in viability observed with Zn2+ is intrinsic in the calculation. Combination of Zn2+ and Cd2+ resulted in survival similar to those obtained by Zn2+ alone (data not shown). Thus, we conclude that Zn2+ can competitively reduce the Cd2+-induced mutagenesis in vivo.

Figure 4.

Effect of zinc on the cadmium-induced inhibition of MMR. (a) Yeast mutator assay using a strain carrying the lys2-10A allele was preformed in the presence of 1 μM Cd2+ and 0–1000 μM Zn2+. The appearance of Lys+ revertant colonies indicates a mutator phenotype. (b) Effect of Zn2+ on the mutator rate of the lys2-10A strain in the presence of Cd2+. Each bar corresponds to the average of three sets of experiments using five independent colonies per set. Rates are calculated as described in Materials and Methods and standard deviation is included at the top of each bar. (c) MSH2–MSH6 (40 nM) was pre-incubated with 50 μM Cd2+ (2/6+Cd), 50 μM Zn2+ (2/6+Zn) or a combination of both (2/6+Cd+Zn) at 4°C for 10 min and assayed for ATPase activity as described in Materials and Methods. To remove excess metal ions, the mixture was dialyzed (denoted by a D in the Figure) extensively and assayed for ATPase activity. (2/6+Cd)D indicates that MSH2–MSH6 was treated with Cd2+ followed by dialysis; (2/6+Zn)D indicates that MSH2–MSH6 was treated with Zn2+ followed by dialysis; (2/6+Cd+Zn)D indicates that MSH2–MSH6 was treated with Cd2+ and Zn2+ followed by dialysis; and (2/6+Cd)D+Zn indicates that MSH2–MSH6 was treated with Cd2+ followed by dialysis, and then treated with Zn2+. A comparison of the ATPase activity of the dialyzed and undialyzed MSH2–MSH6 is shown. The activity of untreated, undialyzed MSH2–MSH6 was used as 100% and corresponds to 26 pmol ATP hydrolyzed. Each set of experiments was repeated three times and the average is presented together with the standard deviation.

Role of Zn2+ in Cd2+ inhibition of MSH2–MSH6 activities

Cd2+ and Zn2+ belong to the same group on the periodic table. Zn2+ is an essential trace element that is required for several cellular functions and has been shown to antagonize the mutagenic effects of Cd2+ (18). In the present study, we determined the effect of Zn2+ on the inhibition of the ATPase activity of MSH2–MSH6 by Cd2+. MSH2–MSH6 protein was pre-incubated with either 50 μM Cd2+ or 50 μM Zn2+ or a combination of both as described in Materials and Methods. The mixture was then dialyzed (denoted by D in Figure 4c) to remove metal ions and tested for ATPase activity. The results (Figure 4c) indicate that at the concentrations used, Zn2+ and Cd2+ resulted in the inhibition of the ATPase activity of MSH2–MSH6 by ∼35% (Figure 4c, 2/6+Cd and 2/6+Zn). However, when the metal ions were used in a combination, the inhibitory effect was greatly enhanced resulting in ∼90% inhibition (Figure 4c, 2/6+Cd+Zn). Dialysis resulted in recovery of the activity to 80–90% of original activity for the single metals [Figure 4c, (2/6+Cd)D and (2/6+Zn)D] and metal combination [Figure 4c, (2/6+Cd+Zn)D], indicating that at the concentrations of metal ions used, the inhibition was reversible. In fact, the addition of Zn2+ to dialyzed Cd2+-treated MSH2–MSH6 yielded an inhibition similar to that obtained by Zn2+ alone [Figure 4c, (2/6+Cd)D+Zn]. When Cd2+ was tested at a higher concentration (0.5 mM), a stronger inhibitory effect was observed, which could only be partially recovered by dialysis (data not shown), suggesting that higher concentration of Cd2+ results in a more severe and irreversible inactivation of MSH2–MSH6.

Effect of sulfhydryl groups on Cd2+-induced inhibition of MSH2–MSH6

Cd2+ has been reported to have a high affinity for sulfhydryl groups (28) and has been proposed to specifically bind free sulfhydryl groups in MMR proteins resulting in inhibition of enzyme activities (20).

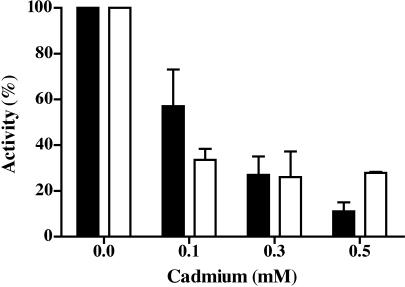

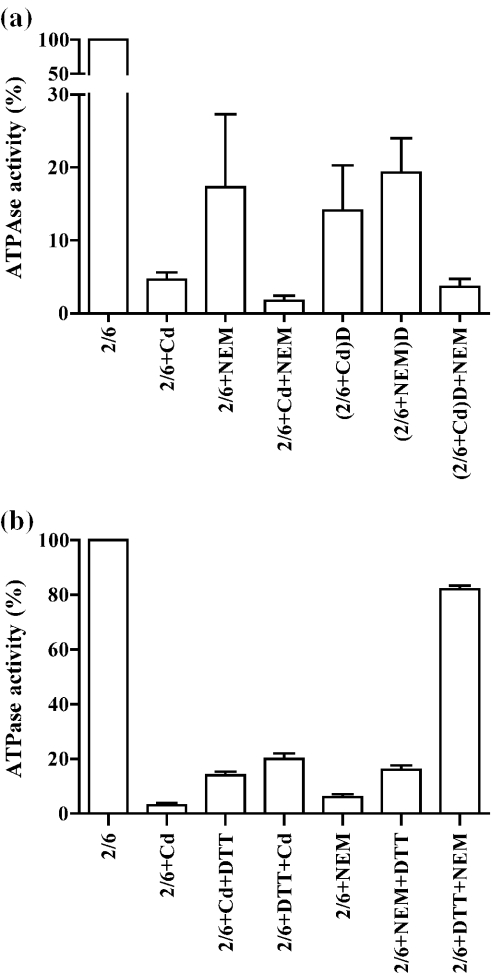

To determine whether Cd2+ inhibits the ATPase activity of MSH2–MSH6 by inactivating sulfhydryl groups, we compared the inhibitory effects of Cd2+ with that exerted by NEM. As described in Materials and Methods, MSH2–MSH6 was pre-incubated with 0.5 mM Cd2+, 0.5 mM NEM or both, and the ATPase activity was determined. As expected, both agents (Figure 5a, 2/6+Cd and 2/6+NEM) significantly inhibited the ATPase activity of MSH2–MSH6 at the concentrations tested (Cd to 5% and NEM to 17% of original activity). When in combination (Figure 5a, 2/6+Cd+NEM), both inhibitors resulted in an increased inactivation of the ATPase activity (2% activity remaining), suggesting that Cd2+ and NEM most likely act at different sites of MSH2–MSH6. When MSH2–MSH6 was pre-incubated with Cd2+ or NEM, followed by dialysis (denoted by D in Figure 5a) recovery of the activity (from 5 to 14% of remaining activity) was observed only for the Cd2+-treated sample [Figure 5a, (2/6+Cd)D], while the NEM treated sample [Figure 5a, (2/6+NEM)D] did not significantly change (from 17 to 19% of activity), suggesting that inhibition by alkylation of sulfhydryl groups by NEM is stable. The dialyzed Cd2+-treated MSH2–MSH6 sample was still inhibited by NEM [Figure 5a, (2/6+Cd)D+NEM], indicating that the target sites for NEM-mediated inhibition are still available, and suggesting that both Cd2+ and NEM interact with different sites in MSH2–MSH6.

Figure 5.

Role of sulfhydryl groups as targets in the inhibition of the ATPase activity of MSH2–MSH6 by cadmium. (a) Comparison of the inhibition of ATPase activity by NEM and Cd2+. MSH2–MSH6 (40 nM) was pre-incubated with 0.5 mM Cd2+ (2/6+Cd), 0.5 mM NEM (2/6+NEM) or a combination of both (2/6+Cd+NEM) at 4°C for 10 min and assayed for ATPase activity. To remove excess NEM and Cd2+, the pre-incubation mixture was extensively dialyzed (denoted as D in the Figure) and assayed for ATPase activity.(2/6+Cd)D indicates that MSH2–MSH6 was treated with Cd2+ followed by dialysis; (2/6+NEM)D indicates that MSH2–MSH6 was treated with NEM followed by dialysis; and (2/6+Cd)D+NEM indicates that MSH2–MSH6 was treated with Cd2+ followed by dialysis, and the treated with NEM. The comparison of the ATPase activities is shown here. The average of three experiments is presented, bars include the standard deviation. (b) Effect of DTT (2 mM) on the inhibition of the MSH2–MSH6 ATPase activity by Cd2+ (0.5 mM) and NEM (5 mM). MSH2–MSH6 (160 nM) was pre-incubated with Cd2+ for 15 min (2/6+Cd), Cd2+ for 15 min followed by DTT for 15 min(2/6+Cd+DTT), DTT for 15 min followed by Cd2+ for 15 min (2/6+DTT+Cd), NEM for 15 min (2/6+NEM), NEM for 15 min followed by DTT for 15 min (2/6+NEM+DTT), and DTT for 15 min followed by NEM for 15 min(2/6+DTT+NEM). The mixtures were then assayed for ATPase activity as described in Materials and Methods. The average of three experiments is presented, including the standard deviation.

To further investigate whether Cd2+ inhibition was in part due to binding to, or oxidation of free sulfhydryl groups, we tested the effect of DTT, a sulfhydryl group-containing disulfide bond reducing agent, on the inhibition of the ATPase activity of MSH2–MSH6. For this purpose, the protein was either pre-incubated with DTT and then treated with either Cd2+ or NEM, or first treated with Cd2+ or NEM followed by the addition of DTT. The ATPase activity was scored and compared to that obtained in reactions where MSH2–MSH6 was not incubated with DTT. When DTT was added after treatment of MSH2–MSH6 with Cd2+, only a slight recovery of the activity (from 4 to 12% of the activity remaining) was observed (Figure 5b, 2/6+Cd and 2/6+Cd+DTT). Similarly, when DTT was added to NEM treated MSH2–MSH6 (Figure 5b, 2/6+NEM and 2/6+NEM+DTT), only a slight recovery of the activity was obtained (from 7 to 16% of the activity remaining). However, DTT was very efficient at preventing the inactivation of MSH2–MSH6 by NEM when present in the reaction at the time of addition of the alkylating agent, resulting in a recovery of 81% of the original ATPase activity (Figure 5b, 2/6+DTT+NEM). Conversely, only a slight recovery of activity (from 4 to 20%) was observed when the protein was pre-incubated with DTT and then treated with Cd2+ (Figure 5b, 2/6+DTT+Cd), suggesting that DTT does not effectively bind to Cd2+ as it does to NEM. These results suggest that Cd2+ inhibits the ATPase activity of MSH2–MSH6 via a mechanism distinct from binding to or oxidation of sulfhydryl groups.

Effect of amino acids on Cd2+ inhibition

To determine whether a specific amino acid residue is a target of Cd2+, we tested if amino acids could prevent the inhibition the MSH2–MSH6 ATPase activity by Cd2+. For this purpose, Cd2+ (0.5 mM) was pre-incubated with 10 mM of each of the essential amino acids (except Tyr) for 30 min at 4°C before the addition of MSH2–MSH6 (160 nM) at 4°C for 10 min. The mixture was then assayed for ATPase activity as described above. Of all the amino acids assayed, cysteine was the most effective at preventing Cd2+ inhibition of the ATPase, resulting in 88% of the activity remaining, versus 7% of remaining activity when no amino acid was added (Table 1). Interestingly, histidine was also effective in binding to Cd2+ and preventing the complete inactivation (33% activity remaining) of the MSH2–MSH6 ATPase activity (Table 1). Other amino acids had no or a marginal effect on preventing the inhibition by Cd2+.

Table 1.

Effect of the essential amino acids on the inhibition of MSH2–MSH6 by cadmium

| Amino acid addeda | % ATPase activity (±SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| −Cd2+b | +Cd2+ | |

| None | 100 | 7 (2.3) |

| Alanine | 138 (8.3)c | 9 (1.6) |

| Arginine | 94 (2.0) | 5 (1.0) |

| Asparagine | 120 (11.5) | 4 (1.2) |

| Aspartic acid | 121 (3.8) | 10 (1.0) |

| Cysteine | 122 (6.0) | 88 (2.7) |

| Glutamine | 125 (3.4) | 6 (0.9) |

| Glutamic acid | 133 (2.3) | 14 (5.0) |

| Glycine | 102 (5.0) | 8 (1.0) |

| Histidine | 113 (4.0) | 33 (2.0) |

| Isoleucine | 100 (1.0) | 6 (0.7) |

| Leucine | 102 (9.8) | 8 (1.1) |

| Lysine | 99 (7.0) | 7 (0.5) |

| Methionine | 110 (16.2) | 9 (1.0) |

| Proline | 105 (7.3) | 7 (1.8) |

| Phenylalanine | 104 (0.6) | 8 (0.9) |

| Serine | 107 (4.0) | 8 (0.1) |

| Threonine | 121 (0.4) | 10 (0.5) |

| Tyrosine | ND | ND |

| Tryptophan | 107 (10.7) | 12 (2.5) |

| Valine | 97 (1.6) | 8 (0.5) |

aAmino acids (10 mM) were pre-incubated with Cd2+ (0.5 mM) for 30 min at 4°C and then with 160 nM MSH2–MSH6 at 4°C for 10 min. The mixture was then incubated with 2 mM [γ32-P]ATP at 37°C for 30 min and spotted on a TLC plate as described in Materials and Methods.

bActivity expressed as percentage of the ATPase activity of MSH2–MSH6 in the absence of Cd2+ and amino acids (100% activity corresponds to 200 pmol ATP hydrolyzed).

cNumbers in parenthesis represent standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

Cd2+ is a naturally occurring type I human carcinogen that is used widely in the industry. Since Cd2+ does not appear to cause a direct mutagenic effect on DNA, it is likely that the carcinogenicity of Cd2+ is via aberrant gene activation, suppressed apoptosis or altered DNA repair (18). Cd2+ was shown to inhibit the eukaryotic MMR pathway (16,22). It was also shown to inhibit a number of other proteins involved in DNA repair, such as apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) endonuclease 1 (Ape1), bacterial formamidopyrimidine–DNA glycosylase (Fpg protein), mammalian XPA protein, as well as the H2O2 induced activation of poly(ADP–ribose)polymerase (29–31). It has also been shown to deregulate the expression of genes involved in controlling cell growth and division (32). Metal ions, such as nickel, selenium and arsenic, have also been proposed as DNA repair inhibitors (33–35). In the current study, we have elucidated the biochemical nature of Cd2+-induced inhibition of MMR.

The primary findings of this study are (i) Cd2+ inhibits the ATP binding and hydrolysis activities of the MMR protein MSH2–MSH6 and is less inhibitory toward the DNA-binding activity of the protein. (ii) The inhibition is concentration and exposure time dependent. (iii) Zn2+ does not protect from the inhibitory effect of Cd2+ in vitro, rather, it exacerbates the inhibition. However, in vivo, the presence of Zn2+ reduces the appearance of mutator phenotype induced by Cd2+ in yeast. (iv) The mechanism of inhibition is distinct from that of NEM, a sulfhydryl group modifier. (v) Cysteine, a sulfur containing amino acid, and histidine are capable of binding to Cd2+ and preventing its inhibitory effect on the ATPase activity of MSH2–MSH6.

The direct inhibition of eukaryotic MMR proteins by metal ions has not been reported widely. We have shown in this study that Cd2+ strongly inhibits the ATPase activity of the MSH2–MSH6 heterodimer. This could be a possible mechanism of inhibition of several of the transition metal ions that have been designated as carcinogens. In addition, we have shown that Cd2+ is less inhibitory toward the DNA-binding activity of MSH2–MSH6, suggesting that ATP hydrolysis defective protein may still recognize and bind to mispaired DNA. A similar effect was seen with vanadate, an inhibitor of bacterial MutS, which inhibited the DNA-binding activity by ∼60%, while the ATPase activity was almost completely abolished (36).

The antagonistic effect of Zn2+ on Cd2+ has been well documented, but has mostly focused on Cd2+ toxicity (18). However, cells exposed to low Cd2+ concentrations (1 μM) do not present a detectable reduction in viability but display a significant increase in the mutator phenotype, indicating that at these low levels, Cd2+ is mutagenic. We demonstrate that the mutagenic effect of Cd2+ in vivo can be efficiently prevented by Zn2+. This is a very important observation, since carcinogenesis by Cd2+ is believed to occur through chronic exposure to low levels of the metal. A recent report presents similar results for human cells (22). A potential mechanism of protection may involve a direct effect of Zn2+ on MSH2–MSH6 protein, since it has been suggested that Cd2+ may exert its carcinogenicity by replacing Zn2+ from zinc finger proteins as well as other binding domains that may be essential for DNA repair (37). However, Zn2+ failed to prevent the inhibitory effect of Cd2+ on the MSH2–MSH6 ATPase activity in vitro. Furthermore, Zn2+ enhanced the inhibitory effect of Cd2+ and was inhibitory on its own. No Zn2+ finger has been described in MSH2–MSH6 and this is consistent with the lack of protection effect by Zn2+ at the protein level. The mechanism by which Zn2+ inhibits MSH2–MSH6 is not known at this time. Other reports of the inhibitory effects of Zn2+ have been published. For example, the Mg2+ dependent (Na+K+) ATPase activity, which is essential for cell excitability, was shown to be competitively inhibited by Zn2+ in electrocytes from Electrophorus electricus (38), and the (Ca2+) ATPase activity of human erythrocyte plasma membrane was also shown to be inhibited by Zn2+ ions (39).

A potential mechanism that explains the reduction of the Cd2+-induced mutagenesis by Zn2+ may involve common transporters, whereby the presence of Zn2+ ions prevents the Cd2+ ions from being transported into the cells. Zn2+ homeostasis is carefully controlled by several mechanisms (40). Zn2+ uptake into the cell is carried out by two membrane transporters, Zrt1 and Zrt2 (41), which have high affinity (Km = 10 nM) and low affinity (Km = 100 nM) for Zn2+, respectively. The expression of these transporters is activated by transcription factor Zap1 when Zn2+ levels are low (40). Conversely, exposing the cell to high levels of Zn2+ (zinc shock) results in a rapid loss of Zrt1 uptake activity and protein (40). This inactivation occurs through zinc-induced endocytosis of the protein and subsequent degradation in the vacuole (40), allowing the cell to tolerate exposure to high levels of Zn2+. In yeast, Cd2+ uptake has been shown to be mediated by the zinc transporter Zrt1 (42,43). This observation is consistent with our findings. We believe that when cells are exposed to high levels of Zn2+ (zinc shock), the Zrt1 transporter is internalized preventing, or significantly reducing the entry of Cd2+. Under these conditions, the levels of intracellular Cd2+ would be too low to inactivate MMR and cause a mutator phenotype. This is consistent with our finding that increasing concentrations of Zn2+ reduce the mutator phenotype. This mechanism also explains why exposure of cells to excess Zn2+ did not result in a mutator phenotype in vivo, although Zn2+ can inactivate the MSH2–MSH6 ATPase activity in vitro. Intracellular Zn2+ is compartmentalized and its level is tightly controlled (40) in such a way that it is unlikely that normally Zn2+ reaches concentrations that interfere with MMR. High levels of Zn2+ are not normally toxic to the cell. However, at very high levels Zn2+ is toxic and results in reduced viability, indicating the inactivation of other essential pathways.

Cd2+ has been reported to react with thiol groups, particularly glutathione (44). In our studies, we have shown that Cd2+ and NEM (a sulfhydryl group alkylating agent) have distinct mechanisms of inhibition of the ATPase activity of MSH2–MSH6 and that the inhibitory effect of NEM but not Cd2+ can be reduced by DTT. Cd2+ seems to be a more effective inhibitor of the ATPase activity of MSH2–MSH6, since higher concentrations of NEM were necessary to exert the same effect. However, when individual amino acids were assayed for their ability to bind Cd2+, cysteine was seen to bind very strongly. These data suggest that Cd2+ may be recognizing additional features in the amino acid residue cysteine, besides its free sulfhydryl group.

Interestingly, histidine was also found to bind to Cd2+. The role of histidine residues in ATP hydrolysis catalysis has been documented. In fact, a mutation of the His728 residue in Taq MutS was shown to almost completely inhibit its ATPase activity (45). Mutation of the equivalent conserved His in hMSH6 (H1248D) was found in an HNPCC patient, while the same in yMSH6 (H1096A) was found to increase the mutation rates (46,47). The binding of Cd2+ to an essential His residue at the ATP binding/hydrolysis site of yeast MSH2–MSH6 could be a possible mechanism of inhibition of this protein and, consequently, of the MMR pathway.

Cys and His are components of zinc finger proteins, and binding of Cd2+ to such proteins has been proposed as a mechanism of inhibition for DNA repair proteins XPA and Fpg (30). Although Zn2+ finger proteins are known to bind to DNA, our studies indicate that Cd2+ does not inhibit the mismatched DNA binding of MSH2–MSH6 as strongly as its ATPase activity. A conserved Phe residue in E.coli MutS, human MSH6 and yeast MSH6 has been shown to be essential for DNA binding (15,48,49). Phe, however, did not bind to Cd2+ in our studies. Thus, it is possible that a zinc finger motif is not involved in DNA binding in the MSH proteins. In bacterial MutS, the ATP-binding domains of both MutS subunits interact with each other and with the DNA-binding regions of both proteins (50,51). This leads to a close connection between ATP/ADP binding and DNA binding that is transferred throughout the protein and affects either activities. Based on this fact, it is possible that Cd2+ binding to Cys and His residues of potential zinc finger domains in MSH2–MSH6 causes a mild defect in DNA binding that is transmitted to the ATP-binding sites of the proteins effectively blocking its ATP binding and hydrolysis activities.

In conclusion, we propose that in the presence of Cd2+, the MSH2–MSH6 protein binds to mispaired DNA. However, as the ATP binding and hydrolysis activities of the protein are abolished, the pathway stalls at this stage resulting in a dominant negative effect and a mutator phenotype. It remains to be determined whether other components of the MMR pathway (e.g. MSH2–MSH3, MLH1–PMS1, EXO1, etc.) are similarly inactivated by Cd2+.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jimmy Ridgeway for the production of the MSH2–MSH6 protein. This research was supported by grant NIH GM068536. H.F.-R. is a Distinguished Cancer Scholar of the Georgia Cancer Coalition. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by NIH grant GM068536.

REFERENCES

- 1.Peltomaki P. Role of DNA mismatch repair defects in the pathogenesis of human cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003;21:1174–1179. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolodner R.D., Marsischky G.T. Eukaryotic DNA mismatch repair. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1999;9:89–96. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)80013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Modrich P., Lahue R. Mismatch repair in replication fidelity, genetic recombination, and cancer biology. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1996;65:101–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.000533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buermeyer A.B., Deschenes S.M., Baker S.M., Liskay R.M. Mammalian DNA mismatch repair. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1999;33:533–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.33.1.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drotschmann K., Yang W., Kunkel T.A. Evidence for sequential action of two ATPase active sites in yeast Msh2–Msh6. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2002;1:743–753. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antony E., Hingorani M.M. Mismatch recognition-coupled stabilization of Msh2–Msh6 in an ATP-bound state at the initiation of DNA repair. Biochemistry. 2003;42:7682–7693. doi: 10.1021/bi034602h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blackwell L.J., Bjornson K.P., Modrich P. DNA-dependent activation of the hMutSalpha ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:32049–32054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.32049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blackwell L.J., Bjornson K.P., Allen D.J., Modrich P. Distinct MutS DNA-binding modes that are differentially modulated by ATP binding and hydrolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:34339–34347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104256200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen D.J., Makhov A., Grilley M., Taylor J., Thresher R., Modrich P., Griffith J.D. MutS mediates heteroduplex loop formation by a translocation mechanism. EMBO J. 1997;16:4467–4476. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.14.4467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gradia S., Acharya S., Fishel R. The human mismatch recognition complex hMSH2–hMSH6 functions as a novel molecular switch. Cell. 1997;91:995–1005. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80490-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Habraken Y., Sung P., Prakash L., Prakash S. ATP-dependent assembly of a ternary complex consisting of a DNA mismatch and the yeast MSH2–MSH6 and MLH1–PMS1 protein complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:9837–9841. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lau P.J., Kolodner R.D. Transfer of the MSH2.MSH6 complex from proliferating cell nuclear antigen to mispaired bases in DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:14–17. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200627200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gu L., Hong Y., McCulloch S., Watanabe H., Li G.M. ATP-dependent interaction of human mismatch repair proteins and dual role of PCNA in mismatch repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1173–1178. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.5.1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Studamire B., Quach T., Alani E. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Msh2p and Msh6p ATPase activities are both required during mismatch repair. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:7590–7601. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drotschmann K., Hall M.C., Shcherbakova P.V., Wang H., Erie D.A., Brownewell F.R., Kool E.T., Kunkel T.A. DNA binding properties of the yeast Msh2–Msh6 and Mlh1–Pms1 heterodimers. Biol. Chem. 2002;383:969–975. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin Y.H., Clark A.B., Slebos R.J., Al-Refai H., Taylor J.A., Kunkel T.A., Resnick M.A., Gordenin D.A. Cadmium is a mutagen that acts by inhibiting mismatch repair. Nature Genet. 2003;34:326–329. doi: 10.1038/ng1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Satarug S., Moore M.R. Adverse health effects of chronic exposure to low-level cadmium in foodstuffs and cigarette smoke. Environ. Health Perspect. 2004;112:1099–1103. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waalkes M.P. Cadmium carcinogenesis. Mutat. Res. 2003;533:107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2003.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Navas-Acien A., Selvin E., Sharrett A.R., Calderon-Aranda E., Silbergeld E., Guallar E. Lead, cadmium, smoking, and increased risk of peripheral arterial disease. Circulation. 2004;109:3196–3201. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000130848.18636.B2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McMurray C.T., Tainer J.A. Cancer, cadmium and genome integrity. Nature Genet. 2003;34:239–241. doi: 10.1038/ng0703-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hopfner K.P., Tainer J.A. Rad50/SMC proteins and ABC transporters: unifying concepts from high-resolution structures. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2003;13:249–255. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(03)00037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lutzen A., Liberti S.E., Rasmussen L.J. Cadmium inhibits human DNA mismatch repair in vivo. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;321:21–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marsischky G.T., Kolodner R.D. Biochemical characterization of the interaction between the Saccharomyces cerevisiae MSH2–MSH6 complex and mispaired bases in DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:26668–26682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.26668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flores-Rozas H., Hurwitz J. Characterization of a new RNA helicase from nuclear extracts of HeLa cells which translocates in the 5′ to 3′ direction. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:21372–21383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bjornson K.P., Modrich P. Differential and simultaneous adenosine di- and triphosphate binding by MutS. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:18557–18562. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301101200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lea D.E., Coulson C.A. The distribution of the numbers of mutants in bacterial populations. J. Genet. 1948;49:264–285. doi: 10.1007/BF02986080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bowers J., Tran P.T., Liskay R.M., Alani E. Analysis of yeast MSH2–MSH6 suggests that the initiation of mismatch repair can be separated into discrete steps. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;302:327–338. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quig D. Cysteine metabolism and metal toxicity. Altern. Med. Rev. 1998;3:262–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McNeill D.R., Narayana A., Wong H.K., Wilson D.M., III Inhibition of Ape1 nuclease activity by lead, iron, and cadmium. Environ. Health Perspect. 2004;112:799–804. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Asmuss M., Mullenders L.H., Eker A., Hartwig A. Differential effects of toxic metal compounds on the activities of Fpg and XPA, two zinc finger proteins involved in DNA repair. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:2097–2104. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.11.2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hartwig A., Asmuss M., Ehleben I., Herzer U., Kostelac D., Pelzer A., Schwerdtle T., Burkle A. Interference by toxic metal ions with DNA repair processes and cell cycle control: molecular mechanisms. Environ. Health Perspect. 2002;110(Suppl. 5):797–799. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110s5797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joseph P., Lei Y.X., Ong T.M. Up-regulation of expression of translation factors—a novel molecular mechanism for cadmium carcinogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2004;255:93–101. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000007265.38475.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wozniak K., Blasiak J. Nickel impairs the repair of UV- and MNNG-damaged DNA. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2004;9:83–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blessing H., Kraus S., Heindl P., Bal W., Hartwig A. Interaction of selenium compounds with zinc finger proteins involved in DNA repair. Eur. J. Biochem. 2004;271:3190–3199. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hwang D.R., Tsai Y.C., Lee J.C., Huang K.K., Lin R.K., Ho C.H., Chiou J.M., Lin Y.T., Hsu J.T., Yeh C.T. Inhibition of hepatitis C virus replication by arsenic trioxide. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004;48:2876–2882. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.8.2876-2882.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pezza R.J., Villarreal M.A., Montich G.G., Argarana C.E. Vanadate inhibits the ATPase activity and DNA binding capability of bacterial MutS. A structural model for the vanadate–MutS interaction at the Walker A motif. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:4700–4708. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hartwig A., Asmuss M., Blessing H., Hoffmann S., Jahnke G., Khandelwal S., Pelzer A., Burkle A. Interference by toxic metal ions with zinc-dependent proteins involved in maintaining genomic stability. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2002;40:1179–1184. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(02)00043-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ribeiro M.G., Pedrenho A.R., Hasson-Voloch A. Electrocyte (Na(+),K(+))ATPase inhibition induced by zinc is reverted by dithiothreitol. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2002;34:516–524. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(01)00153-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hogstrand C., Verbost P.M., Wendelaar Bonga S.E. Inhibition of human erythrocyte Ca2+-ATPase by Zn2+ Toxicology. 1999;133:139–145. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(99)00020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eide D.J. Multiple regulatory mechanisms maintain zinc homeostasis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Nutr. 2003;133:1532S–1535S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.5.1532S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guerinot M.L. The ZIP family of metal transporters. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2000;1465:190–198. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(00)00138-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gitan R.S., Shababi M., Kramer M., Eide D.J. A cytosolic domain of the yeast Zrt1 zinc transporter is required for its post-translational inactivation in response to zinc and cadmium. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:39558–39564. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302760200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gomes D.S., Fragoso L.C., Riger C.J., Panek A.D., Eleutherio E.C. Regulation of cadmium uptake by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1573:21–25. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(02)00324-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chrestensen C.A., Starke D.W., Mieyal J.J. Acute cadmium exposure inactivates thioltransferase (Glutaredoxin), inhibits intracellular reduction of protein–glutathionyl-mixed disulfides, and initiates apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:26556–26565. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004097200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lamers M.H., Georgijevic D., Lebbink J.H., Winterwerp H.H., Agianian B., De Wind N., Sixma T.K. ATP increases the affinity between MutS ATPase domains. Implications for ATP hydrolysis and conformational changes. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:43879–43885. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406380200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berends M.J., Wu Y., Sijmons R.H., Mensink R.G., van der Sluis T., Hordijk-Hos J.M., de Vries E.G., Hollema H., Karrenbeld A., Buys C.H., et al. Molecular and clinical characteristics of MSH6 variants: an analysis of 25 index carriers of a germline variant. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;70:26–37. doi: 10.1086/337944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Das Gupta R., Kolodner R.D. Novel dominant mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae MSH6. Nature Genet. 2000;24:53–56. doi: 10.1038/71684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Malkov V.A., Biswas I., Camerini-Otero R.D., Hsieh P. Photocross-linking of the NH2-terminal region of Taq MutS protein to the major groove of a heteroduplex DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:23811–23817. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dufner P., Marra G., Raschle M., Jiricny J. Mismatch recognition and DNA-dependent stimulation of the ATPase activity of hMutSalpha is abolished by a single mutation in the hMSH6 subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:36550–36555. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005987200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lamers M.H., Perrakis A., Enzlin J.H., Winterwerp H.H., de Wind N., Sixma T.K. The crystal structure of DNA mismatch repair protein MutS binding to a G × T mismatch. Nature. 2000;407:711–717. doi: 10.1038/35037523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Obmolova G., Ban C., Hsieh P., Yang W. Crystal structures of mismatch repair protein MutS and its complex with a substrate DNA. Nature. 2000;407:703–710. doi: 10.1038/35037509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]