Abstract

The protooncogene MYC has been implicated in both the proliferation and programmed cell death of lymphoid cells, and in the genesis of lymphoid tumors. Here, we report that overexpression of MYC, as found in many lymphomas, can break immune tolerance. Mice that would otherwise be tolerant to a transgenic autoantigen mounted an immune response to the antigen if MYC was vigorously expressed in the B cell lineage. The responsive B cells converted to an activated phenotype and produced copious amounts of autoantibody that engendered immune complex disease of the kidney. MYC was required to both establish and maintain the breach of tolerance. These effects may be due to the ability of MYC to serve as a surrogate for cytokines. We found that the gene could mimic the effects of cytokines on both B cell proliferation and survival and, indeed, was required for those effects. These findings demonstrate a critical role for MYC in the response of B cells to antigen and expand the potential contributions of MYC to the genesis of lymphomas.

Keywords: autoimmunity, lymphoma, lymphocyte, anergy, homeostasis

Self tolerance in the B cell compartment can be accomplished by a variety of mechanisms that aim at neutralizing the potentially destructive activities of self-reactive lymphocytes. Such cells can undergo deletion in the bone marrow, editing of the B cell antigen receptor (BCR) on the surface of autoreactive clones to alter their antigenic specificity, Fas-dependent and activation-induced killing of mature cells, and functional anergy (1, 2).

Anergic B cells become refractory to antigenic activation, unless high levels of either multivalent antigen or cytokines are provided in vitro, or high levels of T cell help are provided in vivo (2, 3). The maintenance of the anergic phenotype requires the continuous stimulation of the BCR by a low-avidity cognate antigen (4). This state can be accomplished in part by the alteration of the specificity of the BCR through receptor editing (5, 6).

The MYC gene encodes a 64-kDa transcription factor that is expressed in many tissues (7). MYC was originally identified as the cellular progenitor of the viral oncogene, v-myc, and overexpression of MYC has been implicated in many human tumors (8, 9). Prominent among these tumors are diverse forms of lymphoma (10). Accordingly, the normal function of MYC has been shown to have important roles in the development, proliferation, and survival of lymphocytes (11–13). We found that certain transgenes of MYC can elicit a murine lymphoma with many similarities to Burkitt's lymphoma (BL) (Y.R., J. Duda, K.A.F., and J.M.B., unpublished results). The tumor arises from cooperation between MYC and an autoantigenic stimulus of B cells, which in turn requires a breach of immune tolerance. Here, we demonstrate that the overexpression of MYC itself accounts for the breach of tolerance, and we attribute this effect to the ability of MYC to serve as a surrogate for cytokines.

Materials and Methods

Mice. Mice carrying the Eμ-MYC transgene have been described (14). The TRE-MYC and MMTV-rtTA mice have been described (15, 16). We crossbred these strains to combine the two transgenes in a single strain (MMTV-rtTA/TRE-MYC), in which the B cell-specific expression of the MYC transgene can be repressed by the administration of tetracycline or doxycycline. We also used BCRHEL mice, which express a rearranged BCR from the endogenous Ig promoter, and soluble hen egg lysozyme (sHEL) mice, which ubiquitously express a transgene for the soluble form of hen egg lysozyme under the control of the metallothionein promoter. These two strains have been described (17). All transgenic mouse lines were genotyped by PCR as described (14, 17), except that the Eμ-MYC mouse strain was genotyped by a PCR method using the following primers: Eμ-MYC.1, CAGCTGGCGTAATAGCGAAGAG; Eμ-MYC.2, CTGTGACTGGTGAGTACTCAACC [using the standard PCR conditions described (18)]. The mice in which the c-myc locus was targeted have been described (19). Briefly, the c-mycΔORF allele involved the replacement of the c-myc ORF with a Pgk-Hprt cassette. The hypomorphic c-myc allele (c-mycfloxN) was generated by inserting a Pgk-Neo cassette along with a loxP site into the XhoI site of the third exon of the c-myc locus. The IL-4–/– mice have been described (20). All animals were maintained in accordance with the guidelines of the Committee on Animal Research at the University of California, San Francisco and the National Research Council.

Phenotypic Analysis. The cells present in the lymphoid organs of normal and tumor-bearing mice were immunophenotyped by flow cytometry. Single-cell suspensions were prepared from the lymph nodes, spleens, thymus, and bone marrow. The cell suspensions were incubated with 1:50 dilutions of antibodies on ice for 30 min, and were then washed in FACS buffer (1% BSA in PBS plus 0.05% sodium azide) and fixed in PBS containing 1% paraformaldehyde. Cells were stained with antibodies to one or more of the following markers: B220, Thy1.2, Mac-1, IgM (pan), IgMa, IgMb, IgD (pan) and IgDa, CD4, CD5, CD8, CD19, CD21, CD23, CD25, CD44, CD62L, CD69, CD80, and CD86 (all obtained from Pharmingen). Hen egg lysozyme (HEL) stains were done by incubating cell suspensions with 1 mg/ml HEL (Sigma) in FACS buffer. These cells were washed and incubated with Hy9-biotin (HEL-specific monoclonal antibody, a kind gift from J. Cyster, University of California, San Francisco), followed by streptavidin-phycoerythrin (PE) (Pharmingen).

Serum ELISA. The levels of total serum immunoglobulins were determined by using a capture ELISA, as described (17). The levels of serum anti-HEL antibodies were determined by performing a solid-phase ELISA for HEL, as described (17). Blood samples were obtained from mice and allowed to clot by incubating at room temperature for 2 h. Samples were centrifuged for 30 min at 5,000 × g. Clear supernatants were collected and stored frozen until assayed. ELISAs were set up in triplicate wells. The sera were assayed in two different dilutions (1:300 and 1:900) for HEL reactivity. The sera were diluted starting at 1:100, 2-fold (up to 1:204,800 dilution factor) for the IgM capture assays.

Tissue Processing and Immunofluorescence. Tissues were fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections (4 μM) were stained with hematoxylin/eosin and evaluated for the presence of tumor cells and other abnormalities. Images were acquired with a charge-coupled device camera (Leica) mounted on a phase-contrast microscope.

For immunofluorescence, tissues were cyropreserved by embedding in OCT compound (Tissue-Tek, Torrance, CA) and freezing in liquid nitrogen. Sections (5 μM) were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, blocked in 1% BSA in PBS, and stained with a rhodamine-conjugated donkey anti-IgM (Biomeda, Foster City, CA), and mounted with DAPI-containing medium (Vector Laboratories). Images were acquired with a Leica camera mounted on a fluorescence microscope.

Responses to Antigen in Vivo. Groups of six mice were injected intravenously with 100 μg of HEL protein in PBS 1 or 6 days after receiving a transplant. Alternatively, mice that received transplants of BCRHEL-derived B cells were immunized with 100 μg of HEL protein emulsified in complete Freund's adjuvant (Difco), and administered i.p. The number of responding cells was determined with single-cell suspensions generated from the spleen, or six pooled lymph nodes (pairs of inguinal lymph nodes, axillary and brachial nodes), and counted by using a Coulter counter. The percentage of viable cells was determined by the exclusion of 7-aminoactinomycin-D (7AAD) (Calbiochem), detected by flow cytometry. The nature of the responding cells was determined by flow cytometric analysis of single-cell suspensions prepared from spleens and lymph nodes.

In Vitro Lymphocyte Cultures and B Cell Survival Assays. Single-cell suspensions were prepared from spleens of killed mice. The cell suspensions were incubated with anti-CD4-coated magnetic beads (Dynal, Oslo, Norway) for 45 min at 4°C. The nonadherent cells were washed twice and used as the source of B cells. Cells were labeled with 5- (and 6-)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate, succinimyl ester (CFSE) (Molecular Probes), as described (21, 22).

B cells were activated in vitro by cultivation with 1 μg/ml of anti-CD40 IgM (Pharmingen) and 2 μg/ml anti-IgM-F(ab′)2 (Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 4 days. Cell division profiles were determined by flow cytometric analysis of CFSE. For survival assays, B cells that had been activated for 4 days were washed twice and incubated in complete media. Aliquots were assayed daily for apoptosis with 7-aminoactinomycin-D (Calbiochem) and analyzed by flow cytometry, as described (23–25).

An additional intracellular fluorescent dye, BODIPY red (Molecular Probes) was used to ascertain cell division in retrovirally transduced B cells. In those experiments, activated B cells that had been retrovirally transduced with GFP-expressing retroviruses were labeled with a final concentration of 10 nM BODIPY red, as described (22). We also measured B cell proliferation as determined by the incorporation of [3H]thymidine, as described (18).

Retroviral Vectors and Lymphocyte Infections. Naive B cells were purified and activated as described above. These activated B cells were infected with retrovirus produced in BOSC 23 cells, as described (25). The viral constructs used here included pMIG (25), pMIG-Cre (26), pMIG-MYC (generated by introducing the cDNA for human MYC into the EcoRI site of the pMIG polylinker), and pMIG-Bcl-2 (25).

Results

Overexpression of MYC in an Autoreactive B Cell Background Leads to the Accumulation of Activated B Cells. We initiated this work with a strain of mice that carries three transgenes: Eμ-MYC, which expresses an abundance of MYC in the B cell lineage (14); BCRHEL, which expresses a high-affinity BCR for HEL in B cells (17); and sHEL, which expresses the soluble form of HEL in many tissues (17). These Eμ-MYC/BCRHEL/sHEL animals develop an aggressive B cell tumor that resembles Burkitt's lymphoma of humans (Y.R., J. Duda, K.A.F., and J.M.B., unpublished results). The tumors consist of mature, activated B cells specific to the sHEL autoantigen. The autoreactivity was unexpected because mice that coexpress only the BCRHEL and sHEL transgenes display anergy toward the sHEL autoantigen (17). The anergy is manifested as an absence of the BCRHEL from the surface of B cells, the failure of any B cells to assume the activated phenotype in response to the antigen in vivo, and the absence of a proliferative response to antigen in vitro (6, 17). Thus, it seemed that the overexpression of the Eμ-MYC transgene may have broken tolerance in the tumor-bearing mice.

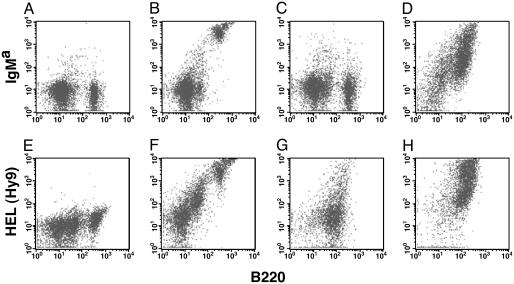

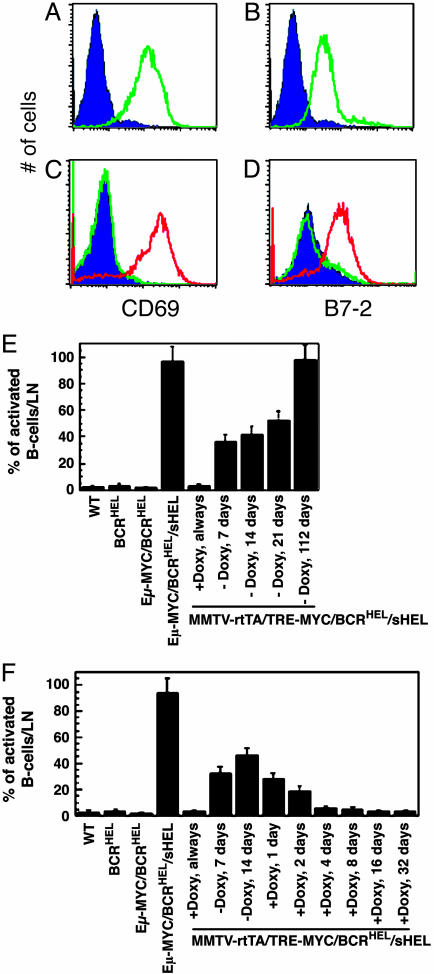

We explored this possibility further by examining the Eμ-MYC/BCRHEL/sHEL mice at an early age, before any evidence of tumor cells. These mice contained an abundance of BCRHEL-specific B cells (Fig. 1D and Table 1), amounts comparable to those found in BCRHEL mice (Fig. 1B and Table 1). Moreover, the Eμ-MYC/BCRHEL/sHEL cells displayed two markers of activation that are characteristically refractory to induction in anergic cells, CD69 and B7-2 (Fig. 2 A and B). As expected, BCRHEL/sHEL mice contained relatively few B cells specific to HEL (Fig. 1C and Table 1). These findings demonstrate that the Eμ-MYC/BCRHEL/sHEL mice do not display the anticipated anergy toward sHEL and raise the possibility that the absence of anergy may be due to the abundant expression of the MYC transgene in B cells.

Fig. 1.

The overexpression of MYC restored BCR expression on the surface of anergic B cells. The presentation of BCRHEL on the surface of splenic B cells was determined by flow cytometry. The mice used in A–D were age-matched females, bred on a C57BL/6 background (IgMb isotype). Staining for flow cytometry was performed with an antibody to the pan B cell marker B220, and an allotype-specific antibody for the BCRHEL transgene (IgMa). (E–H) Mice bearing the MMTV-rtTA and TRE-MYC transgenes were bred on a mixed background. These B cells express both allotypes of IgM, such that IgMa would no longer specifically distinguish the BCRHEL transgene. Staining was with an antibody to B220 and an antibody to HEL (Hy9), to identify antigen bound to the BCRHEL transgene expressed on the surface of the B cells, as described (17). Flow cytometry was performed on spleen cells from a wild-type mouse (C57BL/6) (A), a BCRHEL transgenic mouse (B), a BCRHEL/sHEL mouse (C), an Eμ-MYC/BCRHEL/sHEL mouse (D), wild-type mouse (mixed background) (E), MMTV-rtTA/TRE-MYC/BCRHEL mice that were kept on doxycycline throughout the experiment. (F), MMTV-rtTA/TRE-MYC/BCRHEL/sHEL mice that were kept on doxycycline throughout the experiment (G), or MMTV-rtTA/TRE-MYC/BCRHEL/sHEL mice that had been taken off doxycycline a week before killing (H).

Table 1. Modulation of surface expression of BCR by B cell anergy and MYC.

| Mouse | % B220+/BCRhi | % B220/BCRlo |

|---|---|---|

| WT (C57BL/6) | 0.4 ± 0.1* | 43.0 ± 3.9* |

| BCRHEL | 41.6 ± 4.9* | 2.6 ± 0.8* |

| BCRHEL/sHEL | 9.8 ± 6.4* | 9.3 ± 2.7* |

| Eμ-MYC/BCRHEL/sHEL | 38.1 ± 5.2* | 14.9 ± 4.4* |

| WT (mixed background) | 1.7 ± 0.9† | 39.2 ± 5.2† |

| MMTV-rtTA/TRE-MYC/BCRHEL‡ | 36.4 ± 5.0† | 12.3 ± 3.9† |

| MMTV-rtTA/TRE-MYC/BCRHEL/sHEL‡ | 12.8 ± 3.0† | 44.9 ± 6.8† |

| MMTV-rtTA/TRE-MYC/BCRHEL/sHEL§ | 54.1 ± 7.1† | 11.6 ± 2.8† |

| MMTV-rtTA/TRE-MYC/BCRHEL/sHEL¶ | 68.4 ± 9.2† | 4.9 ± 1.6† |

BCRHEL expression was determined by staining the cells with an antibody to IgMa, an allotypic marker that allows for identification of BCRHEL-expressing cells derived from mice that are predominantly C57BL/6.

BCRHEL expression was determined by staining cells with Hy9, a monoclonal antibody to HEL that allows for recognition of antigen bound to the surface Ig of the B cells, as described in Materials and Methods.

Mice were kept on a doxycycline-containing diet continuously.

Mice were removed from the doxycycline-containing diet 7 days before harvest.

Mice were removed from the doxycycline-containing diet 28 days before harvest.

Fig. 2.

Accumulation of activated B cells after overexpression of MYC.(A and B) Flow cytometric detection of activated B cells. Analyses were performed on lymph node cells obtained from a wild-type mouse (purple trace), and a 4-week-old Eμ-MYC/BCRHEL/sHEL mouse (green trace). Cells were stained with antibodies to two molecules that are up-regulated after the antigen-dependent activation of B cells, CD69 (A), and B7-2 (CD86) (B). The traces represent the levels of CD69 and B7-2 present on the B220+ fraction of the cells, ascertained by gating on the CyChrome C staining cells by flow cytometry. (C and D) Flow cytometric detection of activated B cells. Analyses were performed on lymph node cells obtained from a wild-type mouse (purple trace), an MMTV-rtTA/TRE-MYC/BCRHEL/sHEL mouse that had been kept on doxycycline throughout (green trace), and an MMTV-rtTA/TRE-MYC/BCRHEL/sHEL mouse that had been taken off doxycycline a week before killing (red trace). Cells were stained with antibodies to two molecules that are up-regulated after the antigen-dependent activation of B cells, CD69 (C), and B7-2 (CD86) (D). The traces represent the levels of CD69 and B7-2 present on the B220+ fraction of the cells, ascertained by gating on the CyChrome C staining cells by flow cytometry. (E and F) Activation of B cells in response to HEL. The percentage of activated B cells in lymph nodes was determined as described for A and B. Each data point in these graphs represents the number of activated B cells detected in the lymph nodes of an individual mouse. Cohorts of four mice were used for each time point. The error bars represent the standard deviations obtained from measurements in triplicate. (E) The accumulation of activated B cells after the induction of MYC overexpression in MMTV-rtTA/TRE-MYC/BCRHEL/sHEL mice. (F) Shows the requirement for MYC in the initiation and maintenance of the accumulation of activated B cells in induced MMTV-rtTA/TRE-MYC/BCRHEL/sHEL mice.

The Overexpression of MYC Is Required to Induce the Accumulation of Activated, Self-Reactive B Cells in Vivo. An alternative explanation for our observations with the Eμ-MYC/BCRHEL/sHEL mice is that the overexpression of MYC was able to prevent the onset of anergy in autoreactive B cells, as opposed to reversing the established state of anergy. To assess in a more dynamic manner the ability of MYC to break tolerance, we introduced into BCRHEL/sHEL mice a MYC transgene whose expression in B cells could be repressed by doxycycline. The resulting strain was designated MMTV-rtTA/TRE-MYC/BCRHEL/sHEL (see Materials and Methods and refs. 15 and 16). If expression of the MYC transgene was repressed by doxycycline, B cells were anergic toward HEL, much as in BCRHEL/sHEL mice (Fig. 1 C and G and Table 1). When the expression of MYC was induced by the withdrawal of doxycycline, however, the anergy dissipated: B cells expressing surface BCRHEL became abundant (Fig. 1H and Table 1), and those cells displayed evidence of activation (Fig. 2 A–D). Activated B cells appeared quickly after the induction of MYC and continued to accumulate for at least 112 days (Fig. 2 E and F). The initial appearance of activated B cells starting at 4 days after withdrawal from doxycycline suggest a conversion of anergic cells to the activated state, rather than their replacement by newly generated activated B cells. Subsequent repression of MYC with doxycycline led to a rapid diminution in activated B cells (Fig. 2F). Thus, the effect of MYC was required for both the establishment and maintenance of broken tolerance.

One additional set of experiments was carried out to examine whether the overexpression of MYC may simply prevent the induction of tolerance, rather than allow already tolerant cells to exit that state. To test this notion, we transferred splenic B cells obtained from MMTV-tTA/TRE-MYC/BCRHEL mice into wild-type or sHEL-transgenic recipient mice. In that instance, there are a limited number of HEL-reactive B cells, and only the transplanted B cells would be able to give rise to activated, HEL-specific B cells. The recipient mice that were maintained on a doxycycline-containing diet showed an anergic phenotype, if they contained the sHEL transgene. The mice that were removed from the doxycycline-containing diet, after the anergic B cell phenotype was established, showed many activated B cells that were also HEL-specific (data not shown). These results support the notion that the overexpression of MYC in autoreactive B cells is able to break their tolerance to self antigens and lead to the development of a productive B cell response to a self antigen.

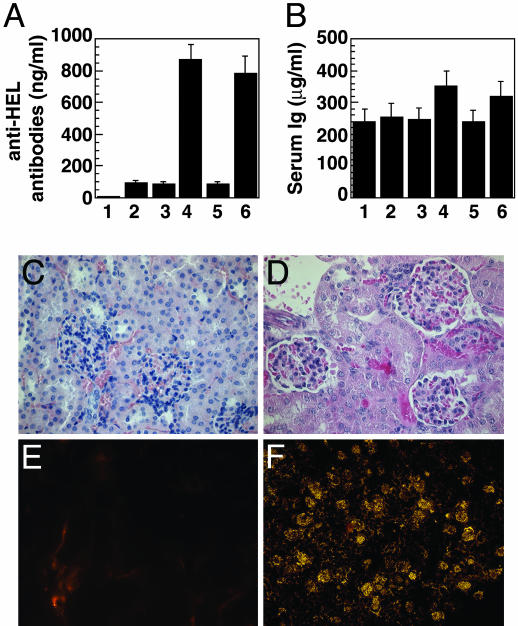

The Activated B Cells That Emerge After Overexpression of MYC Secrete Autoantibodies. We also measured serological manifestations of the B cell response to the HEL autoantigen in Eμ-MYC/BCRHEL/sHEL and MMTV-rtTA/TRE-MYC/BCRHEL/sHEL mice. Overexpression of MYC that was either driven by the Eμ-element, or induced by withdrawal of doxycycline led to a modest elevation of total serum Ig, and HEL-specific antibodies were augmented by a factor of 8 (Fig. 3 A and B). The abundance of HEL-specific circulating antibodies prompted us to examine the kidneys for evidence of immune complex-mediated disease. His-tological examination of kidney sections from Eμ-MYC/BCRHEL/sHEL mice showed glomerular hypercellularity, tubular damage, and proteinaceous aggregates (Fig. 3 C and D). The glomeruli reacted with antisera against IgM (Fig. 3 E and F). The presence of circulating autoantibodies and immune complex-mediated disease in the kidneys of Eμ-MYC/BCRHEL/sHEL mice further support the view that overexpressed MYC in autoreactive B cells was sufficient to break anergy and restore their ability to respond to antigen.

Fig. 3.

Accumulation of autoantibodies in serum and immune complexes in the kidneys after the overexpression of MYC.(A and B) Serological evidence of broken tolerance. Sera were obtained from groups of four mice of each of the specified genotypes, and assayed in triplicate by ELISA against HEL (A), or for total serum Ig (B) (see Materials and Methods). The numbered categories represent sera obtained from wild-type mice (bar 1), BCRHEL mice (bar 2), BCRHEL/sHEL mice (bar 3), Eμ-MYC/BCRHEL/sHEL mice before the development of overt tumors (bar 4), MMTV-rtTA/TRE-MYC/BCRHEL/sHEL mice that had been maintained on doxycycline throughout the course of the experiment (bar 5), and MMTV-rtTA/TRE-MYC/BCRHEL/sHEL mice that had been taken off doxycycline 28 days before collection of sera (bar 6). (C–F) Immune complex renal disease. Histological examination was performed on kidneys taken from either a wild-type mouse (C) or an Eμ-MYC/BCRHEL/sHEL mouse at 6 weeks of age, before the development of tumor (D). The tissues were sectioned and stained with hematoxylin/eosin, and microscopic images were obtained as described in Materials and Methods. Magnification was ×100. For immununofluorescence, kidneys were obtained from a wild-type mouse (E) or an Eμ-MYC/BCRHEL/sHEL mouse (F). Frozen tissues were sectioned and stained with rhodamine-conjugated antibodies to IgM.

MYC Is Required for Cytokine-Dependent Proliferation and Survival of Activated B Cells. It occurred to us that the effect of MYC on tolerance might involve the role of cytokines in B cell function. B cell anergy can be overcome by the addition of high doses of cytokines in vitro (3), or by T cell help in vivo (21, 22, 27). Mindful of prior evidence that MYC could act as an important effector of cytokines (28), we reasoned that the overexpression of MYC might serve as a surrogate signal in the breach of B cell tolerance. We therefore examined the role of MYC in the cytokine-dependent proliferation and survival of B cells after antigenic stimulation.

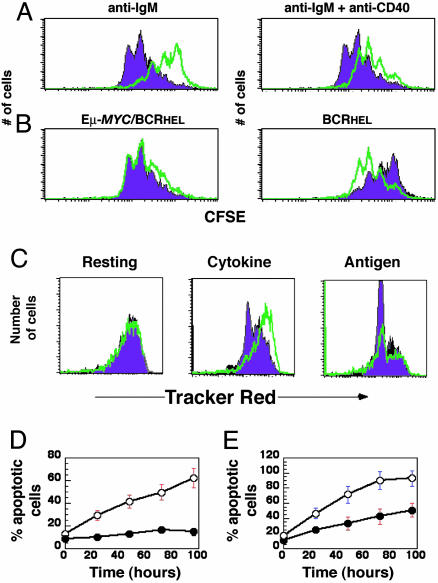

To test the role of MYC in antigen-induced B cell proliferation, we activated naive splenic B cells from either BCRHEL or Eμ-MYC/BCRHEL transgenic mice with mitogenic antibodies directed to IgM and CD40, used individually or together. As shown in Fig. 4A, MYC overexpression resulted in hyperproliferation of B cells after their activation through the B cell receptor. Conversely, we have shown that a reduction of MYC in B cells resulted in decreased proliferative responses (Fig. 6, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site) as found previously in T cells (19). In addition, we noticed that the overexpression of MYC was sufficient to preclude the need for stimulation with antibodies directed at CD40 (Fig. 4B). The B cells obtained from Eμ-MYC/BCRHEL mice proliferated at a maximal rate when stimulated with either antibodies to IgM alone, or antibodies to IgM and CD40, unlike the cells obtained from BCRHEL mice (Fig. 4B). The relative ability of the cells to proliferate in response to antigenic stimulation correlated with the levels of MYC protein detected in cells that either overexpress MYC (Fig. 4 A and B) or have decreased levels of MYC expression (Fig. 6). These results demonstrate that the levels of MYC expression can determine the extent of naive B cell proliferation after encounter with antigen.

Fig. 4.

MYC is an important determinant of B cell proliferation and survival after antigenic stimulation. (A and B) Flow cytometric analysis of cellular proliferation. Splenic B cells were obtained from BCRHEL or Eμ-MYC/BCRHEL mice. The cells were labeled with CFSE and incubated either with antibodies to IgM alone, or a mix of antibodies to IgM and CD40. Flow cytometry was performed after 3 days. (A) The CFSE profile of B cell proliferation for BCRHEL B cells (green trace) and Eμ-MYC/BCRHEL cells by (purple trace). Each peak of the traces represents an additional cell doubling (description of CFSE is contained in Materials and Methods). (B) Overlays the traces obtained for each of the two cell types after stimulation with antibodies to IgM alone (purple trace) or IgM and CD40 (green trace). (C) The effect of MYC on response of B cells to cytokine and antigen. B220+ B cells were activated with antigen and infected with either pMIG (purple traces) or pMIG-Cre (green traces). The cells were then labeled with BODIPY red, incubated overnight with either cytokine or antigen (see Materials and Methods), and analyzed by flow cytometry for GFP expression (to enumerate total cells) and BODIPY red (to detect cellular proliferation). (D and E) Effect of MYC on the survival of B cells. Splenic B cells were activated with antibodies to IgM and CD40 for 4 days. The cells were then washed and incubated in media without added antibodies or growth factors, and assayed for apoptotic cells every 24 h, as described in Materials and Methods.(D) Cells were obtained from MMTV-rtTA/TRE-MYC mice that had either received (clear circles) or not received (filled circles) doxycycline throughout the experiment. (E) Cells were obtained from homozygous c-mycfloxN/floxN mice and then infected with either pMIG (filled circles) or pMIG-Cre (open circles).

B cells that have already undergone antigen-dependent activation and proliferation can be restimulated to proliferate with either cytokines or antigen alone (23–25). To test which of those responses required MYC, we used c-mycfloxN/floxN mice in which both alleles of MYC can be deleted by the enzyme Cre (19). We transduced antigen-activated B cells from these mice with retroviruses that express either GFP or Cre and GFP from a bicistronic message (25). Whereas antigen-activated c-mycfloxN/floxN B cells proliferated in response to cytokines (IL-4), cells from which MYC had been deleted did not (Fig. 4C). In contrast, the response of previously activated lymphocytes to antigen was not dependent upon MYC (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that MYC serves a critical role in cytokine-induced proliferation of activated B cells but is not required for proliferation after the cross-linking of the antigen receptor of previously activated B lymphocytes.

We next tested the role of MYC in B cell survival. We first tested whether MYC was required for the survival effects of cytokines, using labeling with CFSE and 7-aminoactinomycin D to assess proliferation and apoptosis, respectively. MYC overexpression prevented activated B cells from dying when cultured in the absence of added cytokines (Fig. 4D). Conversely, the deletion of MYC using a CRE-expressing retrovirus abrogated the anti-apoptotic effect of cytokines (Fig. 4E). These results demonstrate that MYC is required for the survival of B cells in response to cytokines. In contrast, we did not find an obligatory role for MYC in the Fas-mediated apoptosis of B cells (data not shown).

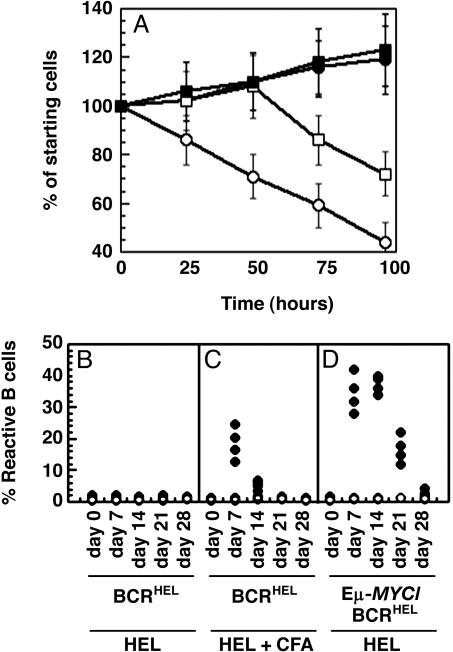

Overexpression of MYC Can Substitute for Cytokine-Dependent Functions in the Proliferation and Survival of Activated B Cells in Vitro. The observations described above indicated that overexpression of MYC could bypass the requirement for cytokines in the proliferation and survival of B cells. To further test this possibility, we obtained splenic B cells from IL-4–/– mice (20). These cells were activated in vitro with mitogenic antibodies to IgM and CD40. In the absence of supplemental cytokines, the percentage of B cells decreased over time (Fig. 5A), due to both a decrease in proliferation and an increase in apoptosis (data not shown). The addition of exogenous cytokines extended the amount of time normal activated B lymphocytes expanded in vitro (Fig. 5A). IL-4–/– B cells showed decreased proliferation and underwent apoptosis sooner than those cells that were supplemented with exogenous IL-4 (Fig. 5A). We found that retrovirus-mediated expression of MYC could promote the expansion of IL-4–/– B cells in the absence of exogenously added cytokines (Fig. 5A), and supplementation with IL-4 had no additional effect (Fig. 5A). The expansion resulted from the combined effects of an increase in proliferation and a decrease in apoptosis (data not shown). These data demonstrate that overexpression of MYC is sufficient to replace the ability of IL-4 to promote the proliferation and survival of activated B cells.

Fig. 5.

Overexpressed MYC can substitute for B cell cytokines in vitro and T cell help in vivo. (A) Substitution of MYC for cytokine in vitro. Splenic B cells were obtained from IL-4–/– mice and infected with either pMIG or pMIG-MYC. The cells were then incubated in the absence of added cytokine (pMIG, open circles; pMIG-MYC, filled circles), or with a single administration of 1,000 units/ml IL-4 at the beginning of the assay (pMIG, open squares; pMIG-MYC, filled squares). Cells were analyzed as in Fig. 4 D and E.(B–D) Substitution of MYC for T cell help in vivo. Spleen and lymph node cells were obtained from either BCRHEL mice (B and C) or Eμ-MYC/BCRHEL mice (D), and transplanted intravenously into wild-type mice. (B–D) The mice were then injected with either 100 μg of HEL protein in PBS (filled circles) or PBS alone (open circles). (C) The mice received i.p. injections of 100 μg of HEL protein emulsified in complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA) (filled circles), or PBS emulsified in CFA (open circles). In all instances, spleen and lymph nodes were collected at the indicated times and analyzed by flow cytometry with antibodies specific for B220 and IgMa (same as for Fig. 1 A–D).

The Overexpression of MYC Renders B Cells Independent of T Cell Help in Vivo. The response of B cells to antigen in vivo requires help by T cells that is mediated by cytokines. Accordingly, we sought to determine whether elevated levels of MYC in B cells could substitute for T cell help in vivo. We transferred control and MYC-expressing HEL-specific B cells into wild-type, syngeneic mice. The recipient mice were then injected with either 100 μg per mouse HEL protein or PBS, and the fate of donor cells was ascertained by detection of IgMa, an allotypic marker that allowed us to identify B cells that express the BCRHEL transgene. In the absence of HEL, the number of donor cells did not change over a 3-week period (Fig. 5 B and C). In mice that had received transplants of Eμ-MYC/BCRHEL B cells and were given a single injection of HEL, the number of donor cells rose for 14 days and then declined (Fig. 5D). The number of cells did not change appreciably in the mice that received transplants of BCRHEL B cells and were given a single injection of HEL (Fig. 5B). Those mice showed a significant increase in the number of HEL-reactive cells only when they were immunized with HEL in the presence of complete Freund's adjuvant, which functions to promote T cell help for B cells (Fig. 5C). We conclude that overexpression of MYC can circumvent the requirement for T cell-derived cytokines in the B cell response to antigens in vivo.

Discussion

We report here that the overexpression of MYC is able to alter the responses of autoreactive B cells and lead to a breach of B cell tolerance. Our findings indicate that the overexpression of MYC is sufficient to bypass the need for cytokine-induced signals or other forms of T cell help, enabling autoreactive B cells to expand in response to their cognate antigen. Our studies indicate that MYC may be an important effector of cytokine receptor functions and, in consequence, an important regulator of B cell homeostasis and tolerance, enabling autoreactive B cells to expand in response to their cognate antigen. These findings expand our understanding on the role of MYC in the response of B cells to antigen and provide an explanation for how overexpression of MYC can break immune tolerance.

The response of B cells to antigen proceeds in two steps. An initial encounter of “naive” B cells with antigen leads to “activation” of the cells and limited proliferation, mediated by the production of cytokines by helper T cells. When activated B cells reencounter the cognate antigen, more vigorous proliferation ensues, driven by signaling from either the BCR or cytokines. Our results suggest that MYC is a necessary mediator of cytokines in the priming of naive B cells and stimulation of previously activated B cells by cytokines, but is not required for the proliferation of activated B cells in response to direct signaling from the BCR. In addition, our results suggest that the overexpression of MYC is able to substitute for cytokine signals. Whereas overexpressed MYC is able to substitute for signals that normally originate from the IL-4 or CD40 receptors, it is also possible that overexpressed MYC is able to promote the proliferative and survival functions associated with those two receptors by activating unrelated signaling pathways. Because large quantities of cytokines can break B cell tolerance (3, 27, 29), it stands to reason that an excess of the necessary effector, MYC, might do so also.

MYC has been implicated previously in the induction of apoptosis under physiologically adverse conditions (30). In contrast, the present work demonstrates that a surfeit of MYC can promote lymphocyte survival in some circumstances, such as the absence of otherwise necessary cytokines. This finding is in accord with previous observations that MYC serves as an effector of cytokine receptor-induced survival of transformed lymphocytic cell lines (31). The data presented here show that MYC is an effector of cytokine functions in primary lymphocytes in vitro and in vivo.

Our results expand the potential contribution of MYC to lymphomagenesis. First, the ability of MYC to replace cytokine function in T and B cells may be a critical step in the development of cytokine-independent clones. This is a necessary prerogative for the genesis of lymphoid tumors (10). Second, the ability of MYC to confer resistance to passive cell death of lymphocytes may help overcome the cell cycle checkpoints that are activated in response to genetic damage. Third, the ability of MYC to break tolerance could expose lymphoid cells to sustained proliferative stimulation by autoantigen, a circumstance that might well favor tumorigenesis in lymphoid lineages.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Cliff McArthur for help with the high-speed cell sorter (MoFlo) and Diana Trail for excellent technical assistance. Y.R. was funded by a Merck Fellowship of the Life Sciences Research Foundation and is currently a Special Fellow of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. A.T. was funded by postdoctoral fellowships from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, the Human Frontiers in Science Program, and the California Division of the American Cancer Society. K.A.F. was funded by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Damon Runyon/Walter Winchell Cancer Research Fund. J.M.B. was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant CA 44338 and by the G. W. Hooper Foundation.

Author contributions: Y.R., K.A.F., B.C.T., and J.M.B. designed research; Y.R., K.A.F., and B.C.T. performed research; Y.R. and A.T. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; Y.R., K.A.F., B.C.T., and A.T. analyzed data; Y.R. and J.M.B. wrote the paper; and J.M.B. supported the research and trained the other authors.

Abbreviations: BCR, B cell antigen receptor; HEL, hen egg lysozyme; sHEL, soluble HEL; CFSE, 5- (and 6-)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate, succinimyl ester.

References

- 1.Pillai, S. (1999) Immunity 10, 493–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodnow, C. C. (1997) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 815, 55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nossal, G. J. (1996) J. Exp. Med. 183, 1953–1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adelstein, S., Pritchard-Briscoe, H., Anderson, T. A., Crosbie, J., Gammon, G., Loblay, R. H., Basten, A. & Goodnow, C. C. (1991) Science 251, 1223–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brink, R., Goodnow, C. C., Crosbie, J., Adams, E., Eris, J., Mason, D. Y., Hartley. S. B. & Basten, A. (1992). J. Exp. Med. 176, 991–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glynne, R., Akkaraju, S., Healy, J. I., Rayner, J., Goodnow, C. C. & Mack, D. H. (2000) Nature 407, 413–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boxer, L. M. & Dang, C. V. T. (1999) Oncogene 20, 5595–5610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nesbit, C. E., Tersak, J. M. & Prochownik, E. V. (1999) Oncogene 13, 3004–3016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pelengaris, S., Khan, M. & Evan, G. I. (2002) Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 764–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Look, A. T. (1997) Science 278, 1059–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donjerkovic, D., Carey, G. B., Mueller, C. M., Liu, S. & Scott, D. W. (2000) Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 252, 151–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Douglas, N. C., Jacobs, H., Bothwell, A. L. & Hayday, A. C. (2001) Nat. Immunol. 2, 307–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Broussard-Diehl, C., Bauer, S. R. & Scheuermann, R. H. (1996) J. Immunol. 156, 3141–3150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adams, J. M., Harris, m A. W., Pikert, C. A., Corcoran, L. M., Alexander, W. S., Cory, S., Palmitter, R. D. & Brinster, R. L. (1985) Nature 318, 533–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felsher, D. W. & Bishop, J. M. (1999) Mol. Cell 4, 199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hennighausen, L., Wall, R. J., Tillman, U., Li, M. & Furth, P. A. (1995) J. Cell Biochem. 59, 463–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodnow, C. C., Crosbie, J., Adelstein, S., Lavoie, T. B., Smith-Gill, S. J., Brink, R. A., Pritchard-Briscoe, H., Wotherspoon, J. S., Loblay, R. H., Raphael, K., et al. (1988) Nature 334, 676–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Refaeli, Y., Van Parijs, L., London, C. A., Tschopp, J. & Abbas, A. K. (1998) Immunity 8, 615–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trumpp, A., Refaeli, Y., Oskarsson, T., Gasser, S., Murphy, M., Martin, G. R. & Bishop, J. M. (2001) Nature 414, 768–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuhn, R., Rajewsky, K. & Muller, W. (1991) Science 254, 707–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ludviksson, B. R., Strober, W., Nishikomori, R., Hasan, S. K. & Ehrhardt, R. O. (1999) J. Immunol. 162, 4975–4982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hodgkin, P. D., Chin, S. H., Bartell, G., Mamchak, A., Doherty, K., Lyons, A. B. & Hasbold, J. (1997) Int. Rev. Immunol. 15, 101–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Refaeli, Y., Van Parijs, L. & Abbas, A. K. (1999) Immunol. Rev. 169, 273–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marrack, P., Mitchell, T., Bender, J., Hilderman, D., Kedl, R., Teague, K. & Kappler, J. (1998) Immunol. Rev. 165, 279–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Parijs, L., Refaeli, Y., Lord, J. D., Nelson, B. H., Abbas, A. K. & Baltimore, D. (1999) Immunity 11, 281–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cherry, S. R., Biniszkeiwicz, D., Van Parijs, L., Baltimore, D. & Jaenisch, R. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 7419–7426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fulcher, D. A., Lyons, A. B., Korn, S. L., Cook, M. C., Koleda, C., Parish, C., Fazekas de St. Groth, B. & Basten, A. (1996). J. Exp. Med. 183, 2313–2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyazaki, T., Liu, Z. J., Kawahara, A., Minami, Y., Yamada, K., Tsujimoto, Y., Barsoumian, E. L., Perlmutter, R. M. & Taniguchi, T. (1995) Cell 81, 223–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ales-Martinez, J. E., Cuende, E, Gaur, A. & Scott, D. W. (1992). Semin. Immunol. 4, 195–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prendergast, G. C. (1999) Oncogene 18, 2967–2987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brandvold, K. A., Ewert, D. L., Kent, S. C., Neiman, P. & Ruddell, A. (2001) Oncogene 20, 3226–3234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.