Abstract

Observational studies have suggested an association between human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and the risk of prostate cancer (PCa). However, the association between HPV infection and the risk of PCa remains unclear. The aim of the present meta-analysis study was to investigate whether HPV serves a role in increasing the risk of PCa. Relevant previous studies up to May 2015 were searched in PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane library, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure, China Wan Fang database and China Biomedical Literature Database. A random-effects model or fixed-effects model was employed to determine odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), when appropriate. Heterogeneity was evaluated using Q and I2 statistical analysis. A total of 24 case-control studies involving 971 patients and 1,085 controls were investigated to estimate the association between HPV infection and PCa risk. The pooled estimate for OR was 2.27 (95% CI, 1.40–3.69). Stratified pooled analyses were subsequently performed according to the HPV detection methods, geographical regions, publication years and types of tissue. Sensitivity analysis based on various exclusion criteria maintained the significance with respect to PCa individually. Little evidence of publication bias was observed. The meta-analysis suggested that HPV infection is associated with increasing risk of PCa, which indicated a potential pathogenetic link between HPV and PCa.

Keywords: human papillomavirus, prostate cancer, meta-analysis

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most frequently diagnosed malignancy and the second cause of cancer-associated mortality in the USA. Until 2015, there were 220,800 estimated new PCa cases, accounting for ~one-quarter of all new diagnoses and 27,540 estimated mortalities in the USA (1). The incidence and mortality rates of PCa account for the second largest proportion of cancer in males worldwide. In 2012, ~1.1 million cases worldwide were diagnosed with PCa and 307,000 males succumb annually to the disease (2). The scale of the PCa population represents an economic burden on health care systems. Family history, advanced age, testosterone, African-American ethnicity, diet and environmental exposure are considered to influence the development of PCa (3). Sutcliffe et al (4) proposed that the sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) may serve an important role in the initiation of PCa. Viral infection may induce chronic and recurrent inflammation of the prostate, and we hypothesize that inflammation of the prostate induced by STDs may increase the risk of PCa. Additionally, HPV has been recognized as the main etiological factor in cervical cancer (5). The E6/E7 oncoproteins of HPV types 16 and 18 have been reported to immortalize prostate epithelial cells (6).

HPV is a small, non-enveloped DNA virus with a circular, double-stranded DNA genome of ~8 kb in size, for which >140 HPV genotypes have been recognized and fully sequenced (7). HPV is one of the most common STDs worldwide (8). Nearly all sexually active individuals may be infected by HPV at some point during their lifetime (9). McNicol and Dodd (10) first detected HPV DNA in prostatic tissues using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in 1990. To date, a growing number of studies have been conducted to investigate the association between HPV infection and PCa, as summarized in a previous review by Ramezani et al (11). However, the association between HPV infection and PCa has not been assessed clearly. The present study performed a meta-analysis to investigate the association between HPV infection and PCa risk.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

Electronic databases, including PubMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/), Web of Science (http://login.webofknowledge.com/), Cochrane library (http://www.cochranelibrary.com/), Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (http://www.cnki.net/), China Wan Fang database (http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn/) and China Biomedical Literature Database (http://www.sinomed.ac.cn/), were searched for relevant clinical articles published up until May 14, 2015. Research studies were selected using the following keywords: ‘Prostate’, ‘HPV’ and ‘human papillomavirus’. Furthermore, reference lists of reviews or studies identified in the literature search were hand-searched for additional studies. There were no publication date restrictions.

Study selection and inclusion criteria

A published study was included in the present study if it met the following requirements: i) A case-control study; ii) conducted on human subjects and written in English or Chinese; iii) no restrictions placed on patients' nationality, ethnicity or age; and iv) histological diagnosis of cases and controls were established. When duplicated studies were identified, only the study published first or the study that provided more detailed information was included (10,12–14).

Data extraction

All data were extracted independently and crosschecked by two authors. The following information was obtained from each study: First author, year of publication, geographical region, type of tissue [paraffin-embedded fixed tissue (PET) or fresh frozen tissue (FF)], HPV detection method, HPV subtypes and the numbers of cases/controls and HPV-positive cases/controls. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and consent with a third author.

Quality assessment

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to assess the quality of individual studies (15). A maximum of 9 points was assigned to each study, 4 for selection, 2 for comparability and 3 for exposure. Scores of 0–3, 4–6 and 7–9 were regarded as low, moderate and high quality, respectively (16).

Statistical analysis

A meta-analysis of the association between HPV infection and the risk of PCa was performed, and odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used as a common measure across studies. Heterogeneity among studies was examined using Cochran's Q test (P<0.10 indicated a high level of statistical heterogeneity) and the I2 statistic (values of 25, 50 and 75% corresponding to low, moderate and high degrees of heterogeneity, respectively) was additionally calculated (17). The random-effects model (DerSimonian and Laird method) (18) took into account when heterogeneity was present among studies. Otherwise, a fixed-effects model (Mantel-Haenszel method) (19) was applied. Stratified pooled analyses were subsequently performed according to the HPV detection method, geographical region, publication year and type of tissue. To evaluate the effect of one single study on the overall risk of PCa, sensitivity analyses were performed by sequential omission of individual studies and the robustness of the pooled estimate was tested. For each pooled analysis, the publication bias was determined from a Begg's (20) funnel plot and Egger's (21) test for the overall study. All analyses were performed using STATA, version 12.0 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA). P<0.05 (two-tailed) was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Eligible studies

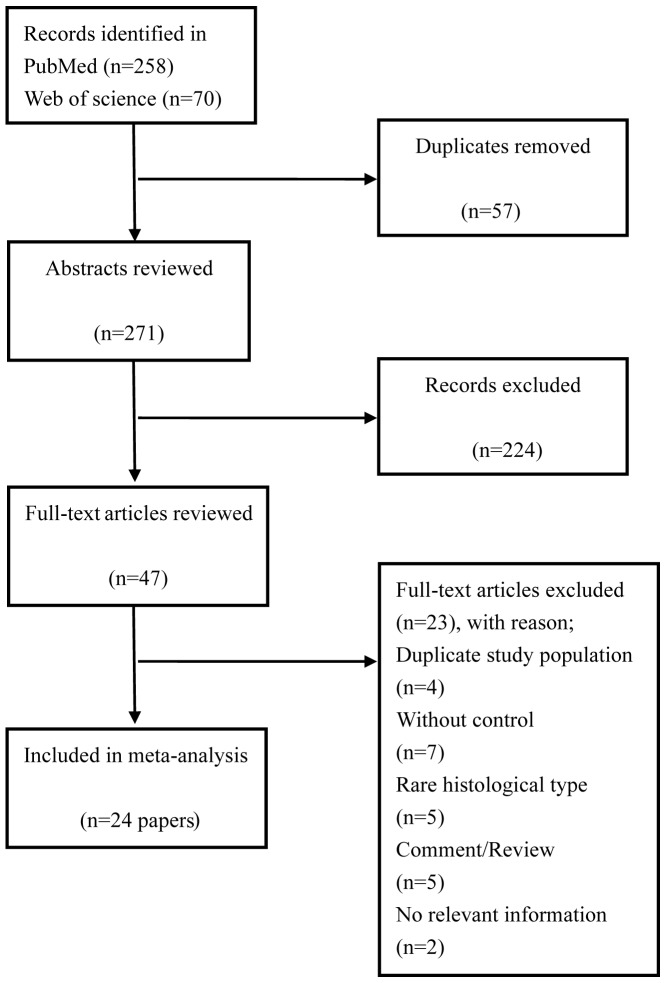

A total of 348 relevant citations were identified at the initial search stage. Following the removal of the duplicates (n=63), 238 studies were excluded based on titles and abstracts review, mainly as they were not relevant to the present analysis. From a full-text review of potentially relevant papers (n=47), 23 studies were excluded based on the following reasons: A total of 4 studies (10,12–14) included the same data as previous articles (22,23), 7 studies lacked a control group (24–30) and 2 studies did not offer the pathological tissue information (31,32); others used bladder cancer cells (33), PCa cells (34) or expressed prostate secretion as the experiment material (35). The last 2 studies were unavailable for analysis (36,37). Finally, 24 papers (6,22,23,38–58) were included in the meta-analysis. The papers included were published between February, 1990 and January, 2015. A detailed flowchart of the selection process is presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Flow-chart of the studies selected.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of all included studies are presented in Table I. These studies were published between 1990 and 2015 and comprised 971 PCa cases in total. The majority of the studies originated from Asia (n=8) (38,40,43–45,48,51,56), Europe (n=7) (22,39,42,47,50,53,55) and North America (n=5) (23,49,52,54,57), and the remaining studies originated from South America (n=1) (46) and Oceania (n=2) (6,41). For the type of PCa or BPH tissue, half of the included studies used formalin-fixed PET (38–42,44,46,48,52,56,57) whereas the others use frozen sections (6,22,23,43,47,49–51,53–55). A total of 2,056 cases were included in the 24 studies investigating the association between HPV infection and risk of PCa (971 were in the case group and 1,085 were in the control group). Within the eligible studies, the prevalence of HPV DNA in PCa varied from 0% (45,48–50,58) to 75% (55).

Table I.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Case (n=971) | Controls (n=1,085) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author/(Refs.), year | Country | Sample | Detection method | HPV type detected | n/Total n | % | n/Total n | % |

| McNicol and Dodd (23), 1991 | Canada | FF | PCR, type-specific primers | 16,18 | 14/27 | 51.9 | 34/56 | 60.7 |

| Masood et al (58), 1991 | USA | FFPE | ISH | 6,11,16,18,31,35 | 0/20 | 0.0 | 0/20 | 0.0 |

| Rotola et al (55), 1992 | Italy | FF | PCR, specific primers | 16 | 6/8 | 75.0 | 14/17 | 82.3 |

| Anwar et al (56), 1992 | Japan | PET | PCR, type-specific primers | 16,18,33 | 28/68 | 41.2 | 0/10 | 0.0 |

| Ibrahim et al (57), 1992 | USA | PET | PCR | 16 | 6/24 | 25.0 | 0/16 | 0.0 |

| Dodd et al (54), 1993 | Canada | FF | PCR | 16 | 3/7 | 42.9 | 5/10 | 50.0 |

| Moyret-Lalle et al (53), 1995 | France | FF | PCR, type-specific | 16.18 | 9/17 | 52.9 | 7/22 | 31.8 |

| Suzuki et al (51), 1996 | Japan | FF | PCR, consensus primers | 16 | 8/51 | 15.7 | 0/51 | 0.0 |

| Wideroff et al (52), 1996 | USA | PET | PCR, consensus primers | 6,11,16,18,31,33,45 | 7/56 | 12.5 | 4/42 | 9.5 |

| Anderson et al (50), 1997 | UK | FF | PCR, type-specific and general primers | 16 | 0/14 | 0.0 | 0/10 | 0.0 |

| Noda et al (48), 1998 | Japan | PET | PCR, consensus primers | 16 | 0/38 | 0.0 | 3/71 | 4.2 |

| Strickler et al (49), 1998 | USA | FF | PCR | 11,16,18, 51,56 | 0/63 | 0.0 | 0/61 | 0.0 |

| Serth et al (22), 1999 | Germany | FF | PCR | 16 | 10/47 | 21.3 | 1/37 | 2.7 |

| Carozzi et al (47), 2004 | Italy | FF | PCR | 6,11,16,18,31,33,35,45,52,58 | 17/26 | 65.4 | 12/25 | 48.0 |

| Leiros et al (46), 2005 | Argentina | PET | PCR | 11.16 | 17/41 | 41.5 | 0/30 | 0.0 |

| Gazzaz and Mosli (45), 2009 | Saudi Arabia | FF | Hybrid Capture | 6,11,16,18,31,33,35,39,40 | 0/6 | 0.0 | 0/50 | 0.0 |

| Chen et al (6), 2011 | Australia | FF | PCR, type-specific | 18 | 7/51 | 13.7 | 3/11 | 27.3 |

| Aghakhani et al (44), 2011 | Iran | PET | PCR, general primers | 6,11,16,18 | 13/104 | 12.5 | 8/104 | 7.7 |

| Tachezy et al (42), 2012 | Czech Republic | PET | PCR, general primers | 16 | 1/51 | 2.0 | 2/95 | 2.1 |

| Salehi and Hadavi (43), 2012 | Iran | FF | PCR, consensus primers | NR | 3/68 | 4.4 | 0/85 | 0.0 |

| Whitaker et al (41), 2013 | Australia | PET | PCR, type-specific primers | 18 | 7/10 | 70.0 | 2/10 | 20.0 |

| Ghasemian et al (40), 2013 | Iran | PET | PCR, general primers | NR | 5/29 | 17.2 | 8/167 | 4.8 |

| Michopoulou et al (39), 2014 | Greece | PET | PCR, general primers | 16,18,31 | 8/50 | 16.0 | 1/30 | 3.3 |

| Singh et al (38), 2015 | India | PET | PCR, type-specific primers | 6,11,16,18 | 39/95 | 41.1 | 11/55 | 20.0 |

PET, paraffin-embedded tissue; FF, fresh frozen; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; ISH, in situ hybridization; NR, not recorded.

Study quality

Table II demonstrated the quality of the included studies. NOS scores ranged from 6–8.

Table II.

Study quality.

| Selection | Comparability | Exposure | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author/(Refs.), year | Adequate definition of cases | Representativeness of case | Selection of controls | Definition of controls | Control for important factors or additional factors | Ascertainment of exposure | Same method of ascertainment for subjects | Non-response rate | Total score | |

| McNicol and Dodd (23), 1991 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |

| Masood et al (58), 1991 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |

| Rotola et al (55), 1992 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | |

| Anwar et al (56), 1992 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |

| Ibrahim et al (57), 1992 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |

| Dodd et al (54), 1993 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |

| Moyret-Lalle et al (53), 1995 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | |

| Suzuki et al (51), 1996 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |

| Wideroff et al (52), 1996 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |

| Anderson et al (50), 1997 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | |

| Noda et al (48), 1998 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | |

| Strickler et al (49), 1998 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | |

| Serth et al (22), 1999 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |

| Carozzi et al (47), 2004 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |

| Leiros et al (46), 2005 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | |

| Gazzaz and Mosli (45), 2009 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | |

| Chen et al (6), 2011 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | |

| Aghakhani et al (44), 2011 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | |

| Tachezy et al (42), 2012 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |

| Salehi and Hadavi (43), 2012 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 | |

| Whitaker et al (43), 2013 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 | |

| Ghasemian et al (40), 2013 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | |

| Michopoulou et al (39), 2014 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | |

| Singh et al (38), 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | |

Meta-analysis results

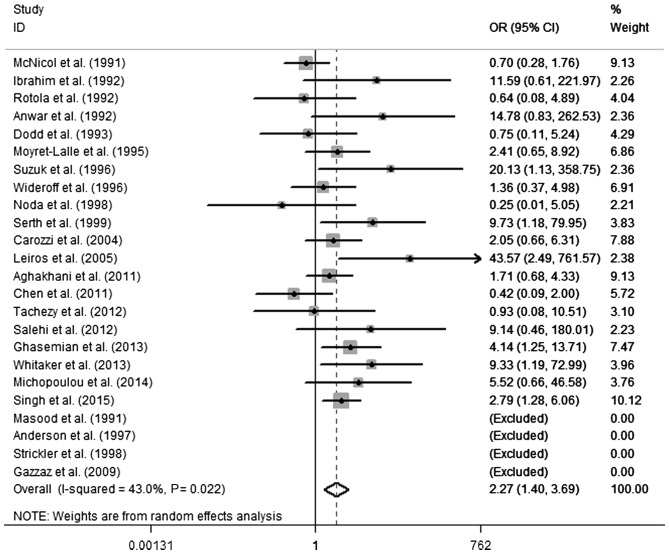

According to the results of the heterogeneity test, there was moderate heterogeneity between the included studies (Q test, P=0.022; I2=43.0%). A random-effects model was selected to evaluate the pooled OR (Fig. 2). The pooled OR of HPV infection was 2.27 (95% CI, 1.40–3.69) in PCa compared with the control, indicating a significant association between HPV infection and PCa. To investigate the sources of heterogeneity, a random-effects meta-regression analysis was performed, including the following variables: HPV DNA detection method, geographical region, publication year and type of tissue. Table III presents the results of the meta-regression for these variables. No statistical significance was identified regarding the differences for the various subgroups and the P-values for publication years, geographical regions and types of tissue were 0.53, 0.08 and 0.21, respectively. A significantly increased PCa risk was revealed in HPV infection when HPV DNA was detected by PCR-based methods (OR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.40–3.69); however, no significance was identified by non-PCR methods. Using non-PCR-based methods, the result was negative in the cases and the controls. When the ORs were pooled by region, heterogeneity was present in Oceania (P=0.018; I2=82.8%). A statically significant association was observed between HPV and PCa in Asia (OR, 2.96; 95% CI, 1.56–5.64) and Europe (OR, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.17–4.47); however, no significant difference was demonstrated in North America (OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.47–2.36) or Oceania (OR, 1.84; 95% CI, 0.09–38.64). Notably, a significantly increased risk was revealed in publications since the year 2000 (OR, 2.65; 95% CI, 1.47–4.85) and there was no significant difference prior to the year 2000 (OR, 1.92; 95% CI, 0.85–4.35). Similarly, an increased PCa risk when HPV infection was present in formalin-fixed PET samples was demonstrated (OR, 2.98; 95% CI, 1.68–5.30), but not in fresh frozen tissue (OR, 1.62; 95% CI, 0.75–3.74).

Figure 2.

Forest plot presenting the association of human papillomavirus infection with the risk of prostate cancer. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; ID, identity.

Table III.

Summary of results.

| Parameter | Studies, n | Study design | Case/control | OR (95% CI) | P-value | P-value of heterogeneity | I2, % | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 24 | Case-control | 971/1085 | 2.27 (1.40–3.69) | 0.001 | 0.022 | 43.0 | |

| HPV DNA methods | NA | |||||||

| PCR | 22 | Case-control | 945/1015 | 2.27 (1.40–3.69) | 0.001 | 0.022 | 43.0 | |

| No PCR | 2 | Case-control | 26/70 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Year of publication | 0.53 | |||||||

| 1990–1999 | 13 | Case-control | 440/423 | 1.92 (0.85–4.35) | 0.117 | 0.046 | 47.7 | |

| 2000–2015 | 11 | Case-control | 531/662 | 2.65 (1.47–4.87) | 0.001 | 0.113 | 37.0 | |

| Geographical region | 0.08 | |||||||

| Asia | 8 | Case-control | 459/539 | 2.96 (1.56–5.64) | 0.001 | 0.257 | 22.6 | |

| Europe | 7 | Case-control | 213/236 | 2.29 (1.17–4.47) | 0.015 | 0.457 | 0.0 | |

| North America | 6 | Case-control | 197/205 | 1.05 (0.47–2.36) | 0.904 | 0.298 | 18.6 | |

| South America | 1 | Case-control | 41/30 | 43.57 (2.49–761.57) | 0.010 | NA | NA | |

| Oceania | 2 | Case-control | 61/21 | 1.84 (0.09–38.67) | 0.694 | 0.018 | 82.8 | |

| Type of tissue | 0.21 | |||||||

| Frozen | 12 | Case-control | 385/435 | 1.62 (0.75–3.74) | 0.216 | 0.052 | 48.0 | |

| Formalin-fixed | 12 | Case-control | 586/650 | 2.98 (1.68–5.30) | 0.000 | 0.184 | 27.3 |

Stratified pooled analyses were used to assess the subgroup differences. OD, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; NA, not available; HPV, human papillomavirus; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

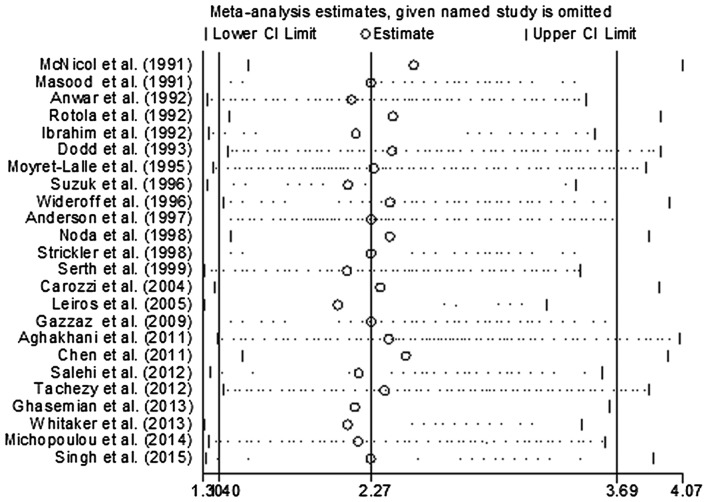

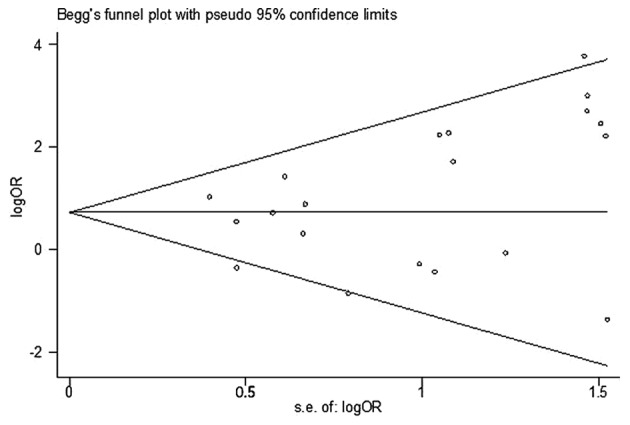

In order to evaluate the influence of each study on the pooled OR, individual studies were sequentially removed from the meta-analysis. Fig. 3 presents the results of the sensitivity analysis. The pooled ORs were stable and demonstrated statistical significance using the fixed-effects model, prior to and following deletion of any signal study. Together, the data indicated that the results of this meta-analysis were reliable and were not overly affected by one of the 24 studies. The funnel plot did not reveal evidence of asymmetry (Fig. 4), and Egger's and Begg's tests indicated that there was no evidence of publication bias (P=0.183 and P=0.135, respectively).

Figure 3.

Sensitivity analysis for individual studies on the summary effect. CI, confidence interval; SE, standard error.

Figure 4.

Begg's funnel plot with pseudo 95% confidence interval of publication bias on the association between human papillomavirus infection and prostate cancer risk. OR, odds ratio.

Discussion

HPV is one of the most commonly diagnosed sexually transmitted infections (STIs) worldwide (59). McNicol and Dodd (10) were the first to detect HPV DNA in prostatic tissue using PCR analysis in 1990. To date, a growing number of studies have been conducted to investigate the association between HPV infection and PCa risk, but results of these studies have often been controversial (11). Generally, HPV infection results in inflammation (60). A previous early study expounded that inflammation is a critical component of tumor progression (61). In the majority of cases, HPV infections are often asymptomatic or self-limited; however, a small number of cases result in a serious burden (62). At present, the majority of studies have focused on female HPV infection (63). However, men can be infected by HPV which is associated with a variety of cancer subtypes, including anal, penile and oral cancer (64). Men serve a key role in spreading HPV to male and female sexual partners (65). A previous study reported a higher rate of PCa in men with a history of exposure to gonorrhea, HPV or any STD (66).

HPV has been established as the main etiological factor in cervical cancer (5) and the association between HPV infection and other types of cancer, including oropharynx (67), breast cancer (68), head and neck cancer (69) and bladder cancer (70), has been studied. Grulich and Vajdic (71) demonstrated that HPV infection induced a marked increase in the prevalence of cervical cancer in immune-compromised patients but not in the prevalence of PCa. The role of HPV may be different in these two types of cancer. Vieira et al (72) suggested that HPV E6 may induce repression of apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme catalytic subunit 3B (APOBEC3B; A3B) gene transcription by functional inactivation of p53 in HPV-positive cervical cancer. Conversely, a previous study indicated that A3B overexpression existed not only in PCa, but also in normal prostate tissues (73), which suggested that there may be a nonsense mutation of A3B in normal prostate tissues. Suzuki et al (51) indicated that p53 gene mutation or the presence of HPV E6 was involved in the development of PCa, but there was no association between p53 mutation and HPV DNA integration. Similarly, Leiros et al (46) revealed that p53 codon 72 allelic frequencies were not observed in prostate hyperplasia and PCa with or without HPV infection. Another previous study (43) demonstrated a similar conclusion. Furthermore, Cantalupo et al (74) investigated The Cancer Genome Atlas database, and revealed a robust expression level of HPV18 genes in cervical cancer tissue samples. They also identified HPV18 transcripts in colon, rectum and normal kidney tissue samples; however, the HPV18 gene expression level was lower compared with that in cervical cancer tissues. The present study also demonstrated that HPVs detected in PCa were found at low levels in certain patients. Overall, HPV may serve various roles in the development of cervical and PCa, and further high quality studies are required.

In a meta-analysis study published in 2011, Lin et al (75) concluded that the causal role of HPV in prostate cancer remained doubtful, as the pooled results of DNA detection method and serologic assays (antibody) were negative; however, no statistical significance was observed in serological assays. The result was positive when the analysis was limited to HPV detection of type 16 infection in PCa tissues (75). Serological testing has the following limitations: i) Antibody cross-reactivity; ii) it is difficult to establish a temporal association between infection and cancer; iii) numerous individuals could be infected by HPV throughout their lifetime, so the control group may be positive; iv) based on a number of etiological studies, it is commonly agreed that HPV does not induce a generalized viremia; and v) only persistent infections induce pathological alterations and serological detection indicates HPV exposure rather than the exact site of infection (76). As a result, studies that used peripheral blood cells and serology were excluded in the present meta-analysis. A similar study by Bae (77) was published in Epidemiology and Health on February 11, 2015, applying a ‘snowballing search strategy’ to search relevant studies from published papers (75,78). Although this method saved energy, studies should be identified again, as different studies have varying inclusion criteria. Additionally, numerous problems remain unsolved: Firstly, whether the risk of PCa with HPV infection varies in different histological types; and secondly, the varied specificity and sensitivity in various HPV DNA detection methods may affect the risk estimation between HPV infection and PCa. Thus, the present study evaluated the association between PCa and HPV infection by considering the heterogeneity of the major associated parameters, including detection method, study region and histological type.

Certain factors may contribute to the variability of results with regard to evaluating the association of HPV infection and PCa. In the present meta-analysis study, stratified analyses were performed according to geographical region, publication year, HPV detection method and type of tissue. The results showed that there were no differences in HPV detection method, geographical region, publication year or type of tissue. The present study suggested a moderate geographical variation in HPV prevalence and association strengths with PCa. A moderate variation of the pooled OR results for various geographical regions was demonstrated and heterogeneity was present in Oceania (P=0.018; I2=82.8%), this may be due to the difference resulting from genetic background, environmental risk factors, including smoking, sexual behavior and other ethnic and cultural differences, as well as other unknown sources. A previous study reported the worldwide prevalence of cervical HPV DNA and also revealed a higher HPV detection rate in Asia and Europe, followed by America (including South American and North American) (79). This analysis suggested that the risks of PCa with HPV infection increased significantly in Asia and Europe, but not in North America and Oceania. The increase is regionally consistent with the association between bladder cancer and HPV infection (70).

In the present meta-analysis, the studies that used PCR-based methods to detect HPV DNA demonstrated a higher sensitivity compared with non-PCR-based methods. This statement could be certified by two specific studies, which employed non-PCR-based methods to detect HPV DNA and obtained negative results in the cases and the controls (45,58). For the PCR-based methods with variation in the types of HPV primers used, type-specific primers may be more sensitive to detect 200 bp shorter HPV DNA sequences compared with consensus primers to amplify 450-bp fragments. The variations in the sensitivity of HPV detection may be due to the differences in amplification efficiency between various types of HPV primers. Therefore, it is possible that the detection rates of HPV using HPV type-specific PCR primers may be higher compared with those using other PCR primers. A similar phenomenon was reported in bladder and ovarian cancer (70,80). This premise is supported by the findings in the present study.

With regard to the publication year, study size was similar prior to and following the year 2000. A significantly increased risk was demonstrated following 2000 (OR, 2.65; 95% CI, 1.47–4.85) and no significant difference was found prior to 2000 (OR, 1.92; 95% CI, 0.85–4.35). With the development of science and technology, the detection method is becoming increasingly sensitive (81). Publication year is a crude evaluation, but this information was not available in previous studies.

Half of the included studies used PET to detect HPV DNA. PET and FF were used for pathological and molecular diagnosis. FF is considered to have the highest quality; however, it is a challenge to isolate highly degraded and cross-linked nucleic acids from FF PET samples for molecular analysis, mainly due to DNA degradation in PET (82). Long DNA fragments are difficult to amplify by consensus primers from PET and type-special primers may be more sensitive for detecting HPV DNA sequences (83). However, the present study revealed that samples from PET had a higher point estimate of OR compared with those from FF samples. This phenomenon may primarily be due to the fact that PET is more easily contaminated than FF. Previous early studies reported that HPV DNA existed on fomites and various medical surfaces (84,85). Future studies should investigate the association between HPV and PCa, in which the aforementioned factors should be taken into account to acquire a more realistic result.

Numerous potential limitations should be acknowledged in the present meta-analysis. Firstly, PCa is multifactorial in etiology, the present meta-analysis was unable to analyze family history, diet, smoking or age, which were also risk factors of PCa, as few of these factors were recorded in the studies that were included. Secondly, a number of limitations also appeared in the detection method of HPV in prostatic tissue: i) Due to the high sensitivity of PCR, contaminated specimens may induce a false positive result, particularly in the earliest studies. Future studies should avoid contamination and record the quality control measures. ii) DNA detection could only determine the current infection status, if a pathogen infected a tissue using a hit-and-run mechanism (86), it may not be detected at the time of analysis. iii) The results may vary depending on the location of the tissue sampling. Finally, for the control group of the included studies, only one study mentioned that the partial normal prostate sample was obtained from autopsy (56) and the majority of the remaining studies included patients with benign prostate hyperplasia (BHP). BHP is the enlargement of the prostate gland by increased tissue mass in the transition zone of the prostate, a prevalent, chronic and progressive disease (87). Preliminary works reported that 11–44% of BHP progressed to PCa within 7 years (88–90). HPV infection was also identified in the BHP tissue samples of the included studies. The present study acknowledged that transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy of the prostate and identification by pathological examination were not 100% sensitive, and that cases of PCa may have been missed. It was not possible to obtain completely normal prostate tissues. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing offered the doctor an opportunity to screen asymptomatic patients; increased levels of serum PSA may indicate PCa. PSA monitoring should be undertaken in a monitoring period could assist in identifying PCa and BHP.

A lack of publication bias suggested that such an association is not an artifact of unpublished negative studies. Furthermore, the association between HPV infection and risk of PCa persists, and remains statistically significant in sensitivity analyses based on various exclusion criteria, which indicated that the results of the present study are robust.

The overall results of the present meta-analysis provided evidence that HPV infection significantly increased the risk of PCa. Tissue-based methods (such as PCR, in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry) and serological assays (such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays and immunofluorescence detection) are basic approaches applied in current research. Further novel laboratory techniques should be performed to confirm the present findings, and the pathogenesis and prognostic role of HPV in PCa requires further investigation, which may lead to a novel horizon. The HPV vaccine, which has already been applied against cervical cancer, may be a novel approach to prevent PCa.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81271917).

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffman RM. Clinical practice. Screening for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2013–2019. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1103642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sutcliffe S, Nevin RL, Pakpahan R, Elliott DJ, Cole SR, De Marzo AM, Gaydos CA, Isaacs WB, Nelson WG, Sokoll LJ, et al. Prostate involvement during sexually transmitted infections as measured by prostate-specific antigen concentration. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:602–605. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Villiers EM, Wagner D, Schneider A, Wesch H, Miklaw H, Wahrendorf J, Papendick U, zur Hausen H. Human papillomavirus infections in women with and without abnormal cervical cytology. Lancet. 1987;2:703–706. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(87)91072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen AC, Waterboer T, Keleher A, Morrison B, Jindal S, McMillan D, Nicol D, Gardiner RA, McMillan NA, Antonsson A. Human papillomavirus in benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostatic adenocarcinoma patients. Pathol Oncol Res. 2011;17:613–617. doi: 10.1007/s12253-010-9357-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tommasino M. The human papillomavirus family and its role in carcinogenesis. Semin Cancer Biol. 2014;26:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Onon TS. History of human papillomavirus, warts and cancer: What do we know today? Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;25:565–574. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Videla S, Darwich L, Cañadas M, Clotet B, Sirera G. Incidence and clinical management of oral human papillomavirus infection in men: A series of key short messages. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2014;12:947–957. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2014.922872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McNicol PJ, Dodd JG. Detection of human papillomavirus DNA in prostate gland tissue by using the polymerase chain reaction amplification assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:409–412. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.3.409-412.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramezani A, Banifazl M, Eslamifar A, Aghakhani A. Association between human papillomavirus infection and risk of prostate cancer. Iranian J Pathol. 2011;1:3–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuczyk M, Serth J, Machtens S, Jonas U. Detection of viral HPV 16 DNA in prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia by quantitative PCR-directed analysis. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2000;3(Suppl 1):S23. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuczyk M, Serth J, Machtens S, Jonas U. Detection viral HPV 16 DNA in prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia by quantitative PCR-directed analysis. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2000;3(Suppl 1):S23. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McNicol PJ, Dodd JG. Detection of papillomavirus DNA in human prostatic tissue by Southern blot analysis. Can J Microbiol. 1990;36:359–362. doi: 10.1139/m90-062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou Q, Luo ML, Li H, Li M, Zhou JG. Coffee consumption and risk of endometrial cancer: A dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13410. doi: 10.1038/srep13410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DerSimonian R, Kacker R. Random-effects model for meta-analysis of clinical trials: An update. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28:105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;22:719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–1101. doi: 10.2307/2533446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Egger M, Smith G Davey, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Serth J, Panitz F, Paeslack U, Kuczyk MA, Jonas U. Increased levels of human papillomavirus type 16 DNA in a subset of prostate cancers. Cancer Res. 1999;59:823–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McNicol PJ, Dodd JG. High prevalence of human papillomavirus in prostate tissues. J Urol. 1991;145:850–853. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)38476-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smelov V, Ouburg S, Pleijster J, Smelova N, Van Moorselaar RJA, Morre SA. Detection of Hr-Hpv Dna in the prostate of men with prostate cancer. Eur Urol Suppl. 2009;8:261. doi: 10.1016/S1569-9056(09)60556-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balis V, Sourvinos G, Soulitzis N, Giannikaki E, SofraS F, Spandidos DA. Prevalence of BK virus and human papillomavirus in human prostate cancer. Int J Biol Marker. 2007;22:245–251. doi: 10.5301/JBM.2008.3639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saad F, Gu K, Jean-Baptiste J, Gauthier J, MesMasson AM. Absence of human papillomavirus sequences in early stage prostate cancer. Can J Urol. 1999;6:834–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarkar FH, Sakr WA, Li YW, Sreepathi P, Crissman JD. Detection of human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA in human prostatic tissues by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) Prostate. 1993;22:171–180. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990220210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Serfling U, Ciancio G, Zhu WY, Leonardi C, Penneys NS. Human papillomavirus and herpes virus DNA are not detected in benign and malignant prostatic tissue using the polymerase chain reaction. J Urol. 1992;148:192–194. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)36551-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Effert PJ, Frye RA, Neubauer A, Liu ET, Walther PJ. Human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 are not involved in human prostate carcinogenesis: Analysis of archival human prostate cancer specimens by differential polymerase chain reaction. J Urol. 1992;147:192–196. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)37195-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tu H, Jacobs SC, Mergner WJ, Kyprianou N. Rare incidence of human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in primary and metastatic human prostate cancer. Urology. 1994;44:726–731. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(94)80215-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinez-Fierro ML, Leach RJ, Gomez-Guerra LS, Garza-Guajardo R, Johnson-Pais T, Beuten J, Morales-Rodriguez IB, Hernandez-Ordoñez MA, Calderon-Cardenas G, Ortiz-Lopez R, et al. Identification of viral infections in the prostate and evaluation of their association with cancer. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:326. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silvestre RV, Leal MF, Demachki S, Nahum MC, Bernardes JG, Rabenhorst SH, Mde A Smith, Mello WA, Guimarães AC, Burbano RR. Low frequency of human papillomavirus detection in prostate tissue from individuals from Northern Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104:665–667. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762009000400024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sinclair AL, Nouri AM, Oliver RT, Sexton C, Dalgleish AG. Bladder and prostate cancer screening for human papillomavirus by polymerase chain reaction: Conflicting results using different annealing temperatures. Br J Biomed Sci. 1993;50:350–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maitland NJ, Macintosh CA, Schmitz C, Lang SH. Immortalization of human prostate cells with the human papillomavirus type 16 E6 gene. Methods Mol Med. 2004;88:275–285. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-406-9:275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smelov V, Gorelov A, Pleijster J, Savicheva A, Pena S, Morre S. The relevance of HPV infection in men with chronic inflammation of the prostate. Eur Urol Suppl. 2007;6:71. doi: 10.1016/S1569-9056(07)60195-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Terris MK, Peehl DM. Human papillomavirus detection by polymerase chain reaction in benign and malignant prostate tissue is dependent on the primer set utilized. Urology. 1997;50:150–156. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00126-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pascale M, Pracella D, Barbazza R, Marongiu B, Roggero E, Bonin S, Stanta G. Is human papillomavirus associated with prostate cancer survival? Dis Markers. 2013;35:607–613. doi: 10.1155/2013/735843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh N, Hussain S, Kakkar N, Singh SK, Sobti RC, Bharadwaj M. Implication of high risk Human papillomavirus HR-HPV infection in prostate cancer in Indian population-A pioneering case-control analysis. Sci Rep. 2015;5:7822. doi: 10.1038/srep07822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Michopoulou V, Derdas SP, Symvoulakis E, Mourmouras N, Nomikos A, Delakas D, Sourvinos G, Spandidos DA. Detection of human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA prevalence and p53 codon 72 (Arg72Pro) polymorphism in prostate cancer in a Greek group of patients. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:12765–12773. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-2604-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghasemian E, Monavari SH, Irajian GR, Nodoshan MR Jalali, Roudsari RV, Yahyapour Y. Evaluation of human papillomavirus infections in prostatic disease: A cross-sectional study in Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:3305–3308. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.5.3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whitaker NJ, Glenn WK, Sahrudin A, Orde MM, Delprado W, Lawson JS. Human papillomavirus and Epstein Barr virus in prostate cancer: Koilocytes indicate potential oncogenic influences of human papillomavirus in prostate cancer. Prostate. 2013;73:236–241. doi: 10.1002/pros.22562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tachezy R, Hrbacek J, Heracek J, Salakova M, Smahelova J, Ludvikova V, Svec A, Urban M, Hamsikova E. HPV persistence and its oncogenic role in prostate tumors. J Med Virol. 2012;84:1636–1645. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salehi Z, Hadavi M. Analysis of the codon 72 polymorphism of TP53 and human papillomavirus infection in Iranian patients with prostate cancer. J Med Virol. 2012;84:1423–1427. doi: 10.1002/jmv.23268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aghakhani A, Hamkar R, Parvin M, Ghavami N, Nadri M, Pakfetrat A, Banifazl M, Eslamifar A, Izadi N, Jam S, Ramezani A. The role of human papillomavirus infection in prostate carcinoma. Scand Int J Infect Dis. 2011;43:64–69. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2010.502904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gazzaz FS, Mosli HA. Lack of detection of human papillomavirus infection by hybridization test in prostatic biopsies. Saudi Med J. 2009;30:633–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leiros GJ, Galliano SR, Sember ME, Kahn T, Schwarz E, Eiguchi K. Detection of human papillomavirus DNA and p53 codon 72 polymorphism in prostate carcinomas of patients from Argentina. BMC Urol. 2005;5:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carozzi F, Lombardi FC, Zendron P, Confortini M, Sani C, Bisanzi S, Pontenani G, Ciatto S. Association of human papillomavirus with prostate cancer: Analysis of a consecutive series of prostate biopsies. Int J Biol Marker. 2004;19:257–261. doi: 10.5301/JBM.2008.3977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Noda T, Sasagawa T, Dong Y, Fuse H, Namiki M, Inoue M. Detection of human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA in archival specimens of benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostatic cancer using a highly sensitive nested PCR method. Urol Res. 1998;26:165–169. doi: 10.1007/s002400050041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Strickler HD, Burk R, Shah K, Viscidi R, Jackson A, Pizza G, Bertoni F, Schiller JT, Manns A, Metcalf R, et al. A multifaceted study of human papillomavirus and prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 1998;82:1118–1125. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19980315)82:6<1118::AID-CNCR16>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Anderson M, Handley J, Hopwood L, Murant S, Stower M, Maitland NJ. Analysis of prostate tissue DNA for the presence of human papillomavirus by polymerase chain reaction, cloning, and automated sequencing. J Med Virol. 1997;52:8–13. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199705)52:1<8::AID-JMV2>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suzuki H, Komiya A, Aida S, Ito H, Yatani R, Shimazaki J. Detection of human papillomavirus DNA and p53 gene mutations in human prostate cancer. Prostate. 1996;28:318–324. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0045(199605)28:5<318::AID-PROS8>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wideroff L, Schottenfeld D, Carey TE, Beals T, Fu G, Sakr W, Sarkar F, Schork A, Grossman HB, Shaw MW. Human papillomavirus DNA in malignant and hyperplastic prostate tissue of black and white males. Prostate. 1996;28:117–123. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0045(199602)28:2<117::AID-PROS7>3.3.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moyret-Lalle C, Marcais C, Jacquemier J, Moles JP, Daver A, Soret JY, Jeanteur P, Ozturk M, Theillet C. ras, p53 and HPV status in benign and malignant prostate tumors. Int J Cancer. 1995;64:124–129. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910640209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dodd JG, Paraskevas M, McNicol PJ. Detection of human papillomavirus 16 transcription in human prostate tissue. J Urol. 1993;149:400–402. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)36103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rotola A, Monini P, Di Luca D, Savioli A, Simone R, Secchiero P, Reggiani A, Cassai E. Presence and physical state of HPV DNA in prostate and urinary-tract tissues. Int J Cancer. 1992;52:359–365. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910520306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Anwar K, Nakakuki K, Shiraishi T, Naiki H, Yatani R, Inuzuka M. Presence of ras oncogene mutations and human papillomavirus DNA in human prostate carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1992;52:5991–5996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ibrahim GK, Gravitt PE, Dittrich KL, Ibrahim SN, Melhus O, Anderson SM, Robertson CN. Detection of human papillomavirus in the prostate by polymerase chain reaction and in situ hybridization. J Urol. 1992;148:1822–1826. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)37040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Masood S, Rhatigan RM, Powell S, Thompson J, Rodenroth N. Human papillomavirus in prostatic cancer: No evidence found by in situ DNA hybridization. South Med J. 1991;84:235–236. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199102000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Colón-López V, Ortiz AP, Del Toro-Mejías LM, García H, Clatts MC, Palefsky J. Awareness and knowledge of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection among high-risk men of Hispanic origin attending a sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinic. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:346. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Baker R, Dauner JG, Rodriguez AC, Williams MC, Kemp TJ, Hildesheim A, Pinto LA. Increased plasma levels of adipokines and inflammatory markers in older women with persistent HPV infection. Cytokine. 2011;53:282–285. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mendoza N, Hernandez PO, Tyring SK. HPV vaccine update: New indications and controversies. Skin Therapy Lett. 2011;16:1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hopkins TG, Wood N. Female human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination: Global uptake and the impact of attitudes. Vaccine. 2013;31:1673–1679. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Colón-López V, Ortiz AP, Palefsky J. Burden of human papillomavirus infection and related comorbidities in men: Implications for research, disease prevention and health promotion among Hispanic men. P R Health Sci J. 2010;29:232–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.de Lima Rocha MG, Faria FL, Goncalves L, Mdo C Souza, Fernandes PÁ, Fernandes AP. Prevalence of DNA-HPV in male sexual partners of HPV-infected women and concordance of viral types in infected couples. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40988. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Taylor ML, Mainous AG, III, Wells BJ. Prostate cancer and sexually transmitted diseases: A meta-analysis. Fam Med. 2005;37:506–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jayaprakash V, Reid M, Hatton E, Merzianu M, Rigual N, Marshall J, Gill S, Frustino J, Wilding G, Loree T, et al. Human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in epithelial dysplasia of oral cavity and oropharynx: A meta-analysis, 1985–2010. Oral Oncol. 2011;47:1048–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li N, Bi X, Zhang Y, Zhao P, Zheng T, Dai M. Human papillomavirus infection and sporadic breast carcinoma risk: A meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;126:515–520. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1128-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.O'Rorke MA, Ellison MV, Murray LJ, Moran M, James J, Anderson LA. Human papillomavirus related head and neck cancer survival: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Oncol. 2012;48:1191–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li N, Yang L, Zhang Y, Zhao P, Zheng T, Dai M. Human papillomavirus infection and bladder cancer risk: A meta-analysis. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:217–223. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Grulich AE, Vajdic CM. The epidemiology of cancers in human immunodeficiency virus infection and after organ transplantation. Semin Oncol. 2015;42:247–257. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vieira VC, Leonard B, White EA, Starrett GJ, Temiz NA, Lorenz LD, Lee D, Soares MA, Lambert PF, Howley PM, Harris RS. Human papillomavirus E6 triggers upregulation of the antiviral and cancer genomic DNA deaminase APOBEC3B. MBio. 2014;5(pii):e02234–e14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02234-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gwak M, Choi YJ, Yoo NJ, Lee S. Expression of DNA cytosine deaminase APOBEC3 proteins, a potential source for producing mutations, in gastric, colorectal and prostate cancers. Tumori. 2014;100:112e–117e. doi: 10.1700/1636.17922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cantalupo PG, Katz JP, Pipas JM. HeLa nucleic acid contamination in the cancer genome atlas leads to the misidentification of human papillomavirus 18. J Virol. 2015;89:4051–4057. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03365-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lin Y, Mao Q, Zheng X, Yang K, Chen H, Zhou C, Xie L. Human papillomavirus 16 or 18 infection and prostate cancer risk: A meta-analysis. Ir J Med Sci. 2011;180:497–503. doi: 10.1007/s11845-011-0692-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Simen-Kapeu A, Surcel HM, Koskela P, Pukkala E, Lehtinen M. Lack of association between human papillomavirus type 16 and 18 infections and female lung cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1879–1881. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bae JM. Human papillomavirus 16 infection as a potential risk factor of prostate cancer: An adaptive meta-analysis. Epidemiol Health. 2015;37:e2015005. doi: 10.4178/epih/e2015005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hrbacek J, Urban M, Hamsikova E, Tachezy R, Heracek J. Thirty years of research on infection and prostate cancer: No conclusive evidence for a link. A systematic review. Urol Oncol. 2013;31:951–965. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bruni L, Diaz M, Castellsagué X, Ferrer E, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S. Cervical human papillomavirus prevalence in 5 continents: Meta-analysis of 1 million women with normal cytological findings. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:1789–1799. doi: 10.1086/657321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Svahn MF, Faber MT, Christensen J, Norrild B, Kjaer SK. Prevalence of human papillomavirus in epithelial ovarian cancer tissue. A meta-analysis of observational studies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014;93:6–19. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Abreu AL, Souza RP, Gimenes F, Consolaro ME. A review of methods for detect human papillomavirus infection. Virol J. 2012;9:262. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kalmár A, Péterfia B, Wichmann B, Patai ÁV, Barták BK, Nagy ZB, Furi I, Tulassay Z, Molnár B. Comparison of automated and manual DNA isolation methods for DNA methylation analysis of biopsy, fresh frozen and formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded colorectal cancer samples. J Lab Autom. 2015;20:642–651. doi: 10.1177/2211068214565903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mori S, Nakao S, Kukimoto I, Kusumoto-Matsuo R, Kondo K, Kanda T. Biased amplification of human papillomavirus DNA in specimens containing multiple human papillomavirus types by PCR with consensus primers. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1223–1227. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.01922.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Strauss S, Sastry P, Sonnex C, Edwards S, Gray J. Contamination of environmental surfaces by genital human papillomaviruses. Sex Transm Infect. 2002;78:135–138. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.2.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ferenczy A, Bergeron C, Richart RM. Human papillomavirus DNA in fomites on objects used for the management of patients with genital human papillomavirus infections. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;74:950–954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Iwasaka T, Hayashi Y, Yokoyama M, Hara K, Matsuo N, Sugimori H. ‘Hit and run’ oncogenesis by human papillomavirus type 18 DNA. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1992;71:219–223. doi: 10.3109/00016349209009922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Thorpe A, Neal D. Benign prostate hyperplasia. Lancet. 2003;361:1359–1367. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Boddy JL, Pike DJ, Malone PR. A seven-year follow-up of men following a benign prostate biopsy. Eur Urol. 2003;44:17–20. doi: 10.1016/S0302-2838(03)00205-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Brossner C, Madersbacher S, de Mare P, Ponholzer A, Al-Ali B, Rauchenwald M. Follow-up of men obtaining a six-core versus a ten-core benign prostate biopsy 7 years previously. World J Urol. 2005;23:419–421. doi: 10.1007/s00345-005-0025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Durkan GC, Greene DR. Elevated serum prostate specific antigen levels in conjunction with an initial prostatic biopsy negative for carcinoma: Who should undergo a repeat biopsy? BJU Int. 1999;83:34–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.00864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]