Abstract

Tumor protein p53 has been intensively studied as a major tumor suppressor. The activation of p53 is associated with various anti-neoplastic functions, including cell senescence, cell cycle arrest, apoptosis and inhibition of angiogenesis. However, the role of p53 in cancer cell chemosensitivity remains unknown. Cholangiocarcinoma cell lines QBC939 and RBE were grown in full-nutrient and nutrient-deprived conditions. The cell lines were treated with 5-fluorouracil or cisplatin and the rate of cell death was determined in these and controls using Cell Counting Kit-8 and microscopy-based methods, including in the presence of autophagy inhibitor 3MA, p53 inhibitor PFT-α or siRNA against p53 or Beclin-1. The present study demonstrated that the inhibition of p53 enhanced the sensitivity to chemotherapeutic agents in nutrient-deprived cholangiocarcinoma cells. Nutrient deprivation-induced autophagy was revealed to be inhibited following inhibition of p53. These data indicate that p53 is important for the activation of autophagy in nutrient-deprived cholangiocarcinoma cells, and thus contributes to cell survival and chemoresistance.

Keywords: autophagy, p53, cholangiocarcinoma, chemotherapy, nutrient deprivation

Introduction

Autophagy is a highly conserved lysosomal pathway that is crucial for maintaining cellular homeostasis and cell survival in stress conditions (1). In the autophagic process, degraded organelles and cytoplasmic proteins are phagocytosed in autophagosomes, double-membrane vesicles, which then fuse with lysosomes to convert them into autolysosomes. Phagocytosis digests material in autolysosomes to amino acids and molecular precursors for cell anabolism. In the majority of cell types, autophagy occurs at low levels to maintain homeostasis and facilitate differentiation and developmental processes (2). Abnormalities of autophagy may result in disease, including cancer, neurodegeneration, infectious disease and heart disease (3). Emerging evidence suggests that autophagy may contribute to tumor cell resistance to radiation and chemotherapy (4).

Autophagy may be regulated by various oncogenes (5). Wild-type tumor protein p53 serves a dual role in regulating autophagy depending on its subcellular localization (6). Autophagy may be induced by p53 via transcription-dependent or independent pathways (7), whereas inhibiting the activity of p53 has also been demonstrated to be sufficient to activate autophagy (8).

Although activation of p53 is associated with tumor-suppressive functions, including cell senescence, cell cycle arrest, apoptosis and inhibition of angiogenesis (9), a recent study has illustrated that p53 can also promote cell survival (10). With reference to its effect in autophagy, it is hypothesized that p53 serves a significant role in cancer cell survival during chemotherapy in specific conditions. In the present study, the role of p53-induced autophagy in nutrient deprivation was explored and the effect of p53 inhibition on chemosensitivity in cholangiocarcinoma cells under nutrient-deprived conditions was examined.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and reagents

Human cholangiocarcinoma cell lines QBC939 and RBE, which possess wild-type p53 (11,12), were obtained from the Tumor Immunology and Gene Therapy Center of the Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital (Shanghai, China). The cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Shanghai Excell Biology, Shanghai, China), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin [designated as the full-nutrient (FN) medium] in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37°C. The cells were treated with culture media containing 120 µg/ml 5-fluorouracil (5FU) or 8 µg/ml cisplatin 24 h after seeding. Nutrient deprivation was induced by growth in a nutrient-free (NF) medium composed of Earle's balanced salt solution (EBSS), which was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). 5FU and cisplatin were purchased from Qilu Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Jinan, China). 3-methyladenine (3MA, 10 mM) was obtained from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX, USA), as the inhibitor of autophagy. Pifithrin-α (PFT-α) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck Millipore). PFT-α was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck Millipore).

Cell viability assay

The measurement of the percentage of viable cells was assessed with a Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Dojindo Molecular Technology, Inc., Kumamoto, Japan), as previously described (13). QBC939 and RBE cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at 5×103 cells per well. When cell density reached 80%, fresh medium containing 5FU or cisplatin was added to the cells. Cell viability was measured using the CCK-8 assay subsequent to incubation with the drugs for 24 h. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm with a microtiter plate reader.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as described previously (14) using antibodies specific for p53 (cat. no. P9249, Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA-Aldrich; Merck Millipore). QBC939 and RBE cells were cultured in FN or NF media for 24 h. The harvested cells were washed with PBS twice and lysed on ice for 30 min with whole cell extract lysis buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA). Lysates were centrifuged at 16,099 × g for 10 min at 4°C and the protein concentration was determined by a bicinchoninic acid kit for Protein Determination (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Cell lysates were mixed with loading buffer and heated for 5 min at 100°C. Protein samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked in blocking buffer (TBS, 0.1% Tween-20 and 5% skimmed milk powder) for 1 h and then incubated overnight at 4°C with the specific p53 antibody (dilution, 1:1,000). Following three washes in TBS/0.1% Tween-20, the membranes were incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody against rabbit IgG (cat. no. sc-2005; dilution, 1:2,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) for 1 h at room temperature. Following three further washes in TBS/0.1% Tween-20, the membranes were detected by chemiluminescence using Western Blotting Luminol Reagent (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.).

Transient transfection

Microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3) is a commonly used molecular marker for autophagy. Plasmids expressing green fluorescent protein-tagged microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (GFP-LC3; Shanghai, China Institute for Biological Sciences, Shanghai, China) were transiently transfected into cholangiocarcinoma cells as previously described (14). Cells were incubated with cisplatin or fluorouracil (Qilu Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.) for 3 days and transfected with the GFP-LC3 plasmid. After 24 h, the cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and mounted for confocal microscopy. GFP fluorescence was observed under a confocal microscope (TCS SP8; Leica Microsystems, Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL, USA). Autophagic cells were counted as those that exhibited punctate fluorescence from GFP-LC3.

Cell apoptosis assay

Apoptosis detection by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) staining was performed as described (14). QBC939 cells cultured with 5FU or cisplatin were fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature. Fixed cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. After being washed with PBS, cells were incubated with 1 µg/ml of DAPI for 10 min and then washed three times in PBS. Cell morphology was observed with a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss GmbH, Jena, Germany). Photomicrographs were taken with a digital camera (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Transmission electron microscopy

Cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in phosphate buffer and stored at 4°C until embedding. Cells were post-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide followed by increasing gradient dehydration steps using ethanol and acetone. Cells were subsequently embedded in araldite and ultrathin sections (50–60 nm) were obtained, placed on uncoated copper grids and stained with 3% lead citrate-uranyl acetate. Images were examined with a CM-120 transmission electron microscope (Philips Medical Systems B.V., Eindhoven, The Netherlands).

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) transfection

Beclin-1 is a key protein in the process of autophagy (14). The Stealth RNAi™ negative control duplex (cat. no. 12935-200) and siRNA duplex oligoribonucleotides targeting human Beclin-1 (cat. no. 1299003) were obtained from Invitrogen (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and siRNA-p53 (cat. no. 13750047) from Ambion (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The siRNA was transfected into cholangiocarcinoma cells using siRNA Transfection Reagent (cat. no. sc-29528; Santa Cruz, Biotechology, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Statistical analysis

Values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis between two groups was performed using a Student's t-test, and multiple groups were compared by one-way analysis of variance, using SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P<0.05 was considered to represent a statistically significant difference.

Results

Nutrient-deprived conditions induce autophagy in cholangiocarcinoma cells

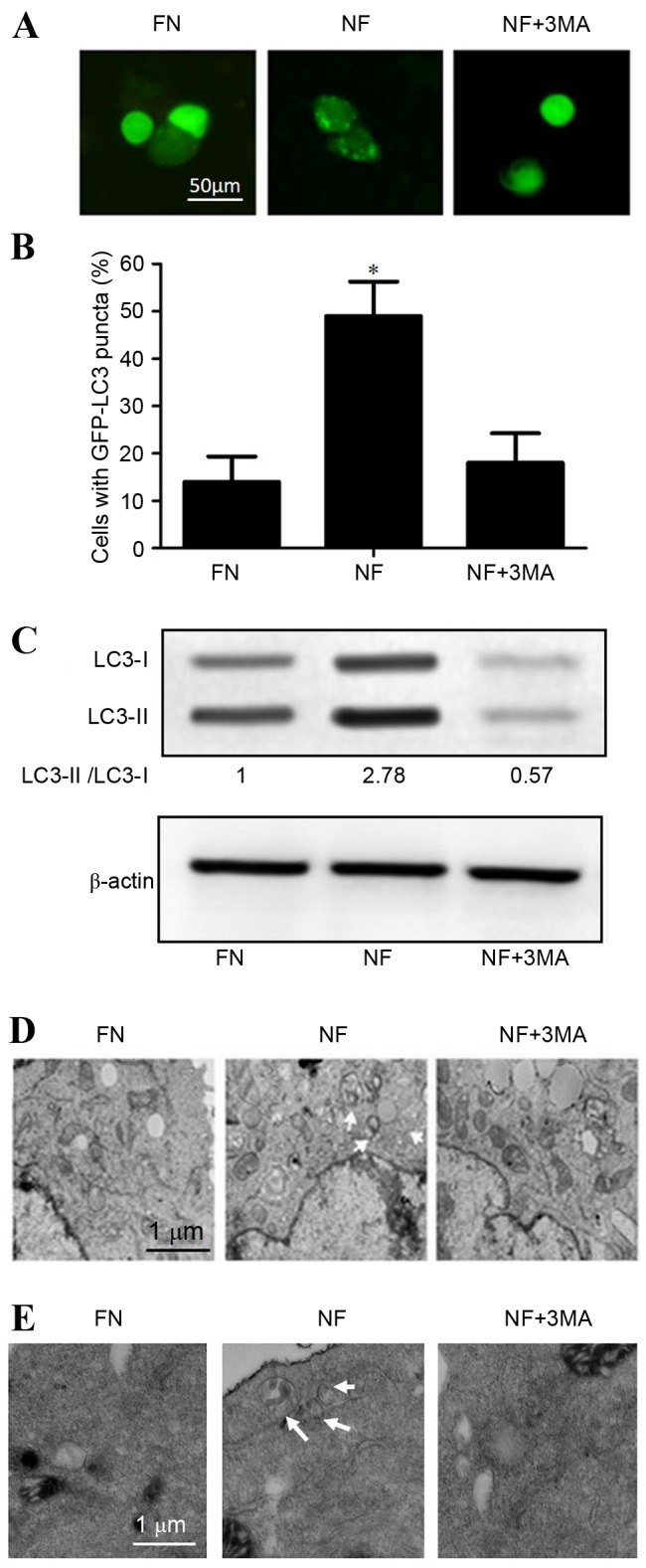

To confirm the role of autophagy in nutrient-deprived conditions, cholangiocarcinoma cell lines were transfected with GFP-LC3 plasmids following culture for 12 h in FN or NF medium. Fluorescence microscopy results revealed that the NF condition comprised a significantly higher percentage of cells containing GFP puncta (P<0.05) compared with cells grown in the FN medium, which predominantly exhibited a diffuse GFP distribution. Treatment with the autophagy inhibitor 3-methyladenine (3MA) decreased the proportion of cells containing GFP-LC3 puncta among the NF medium-treated QBC939 cells compared with NF treatment alone (48.27–19.24%; Fig. 1A and B).

Figure 1.

Nutrient-deprived conditions induced autophagy in cholangiocarcinoma cells. Nutrient deprivation conditions induced autophagy in QBC939 and RBE human cholangiocarcinoma cells cultured for 12 h in FN or NF medium, or NF medium containing the autophagy inhibitor 3MA. (A) QBC939 cells were transfected with GFP-LC3 plasmids and GFP-LC3 fluorescence was evaluated by fluorescence microscopy. Representative images are presented. (B) The percentages of GFP-positive cells that exhibited punctate GFP-LC3 fluorescence, indicating the presence of autophagosomes, were evaluated; cells with >2 autophagosomes per cell were scored as exhibiting an autophagic reaction. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of ≥3 independent experiments. *P<0.05 vs. FN group. (C) Whole cell lysates from RBE cells were subjected to western blotting to analyze LC3-I and LC3-II levels. β-actin was included as a loading control. Representative transmission electron microscopy images are presented for (D) QBC939 cells and (E) RBE cells. Arrows indicate autophagosomes. FN, full-nutrient; NF, nutrient-free; 3MA, 3-methyladenine (10 mM); GFP-LC3, green fluorescent protein-tagged LC3; LC3, microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3.

Western blot analysis of LC3 revealed that the protein expression level of LC3-II was significantly increased in the nutrient-deprived condition in RBE cells (P<0.05; Fig. 1C). Furthermore, electron microscopy analysis demonstrated that the number of observable autophagosomes in EBSS-treated cholangiocarcinoma cells increased (Fig. 1D and E). Taken together, these observations suggest that autophagy may be activated by nutrient-deprived conditions in cholangiocarcinoma cells.

Inhibition of autophagy enhances the sensitivity to chemotherapy of cholangiocarcinoma cells in a nutrient-deprived condition

The rate of cell death after chemotherapy in different nutritional conditions was investigated. QBC939 and RBE cells were cultured in FN or NF medium and treated with 120 µg/ml 5FU or 8 µg/ml cisplatin for 12 h. As presented in Fig. 2A, the cell death rate of chemotherapy-treated cholangiocarcinoma cells was significantly reduced in the cells growing in a nutrient-deprived environment (P<0.05), which demonstrated the greater resistance to chemotherapy of cells in nutrient-deprived conditions.

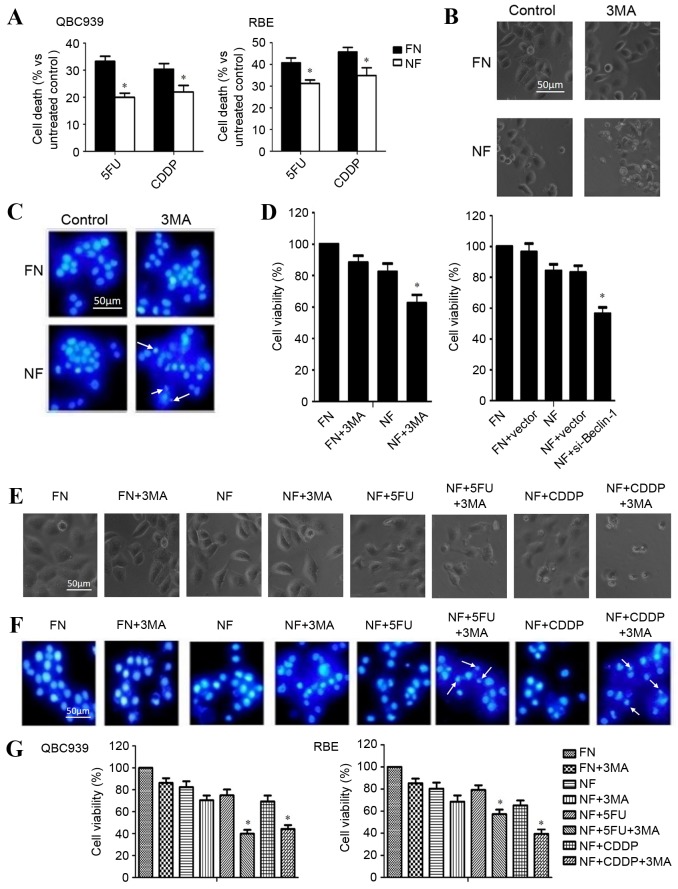

Figure 2.

Inhibition of autophagy enhanced the chemosensitivity of cholangiocarcinoma cells in nutrient-deprived conditions. (A) QBC939 and RBE cells were cultured in FN or NF media, then treated with 5FU or CDDP for 12 h. Cell viability was determined by a CCK-8 assay. Data are presented as the mean + SD of ≥3 independent experiments. (B) QBC939 cell morphological changes were detected by inverted phase contrast microscopy following treatment with the autophagy inhibitor 3MA. Representative images are presented. (C) Nuclei were visualized with DAPI staining following treatment with 3MA or a control. Representative images are presented. Arrows indicate apoptotic bodies. (D) Cell viability was evaluated using a CCK-8 assay following treatment with 3MA, or transfection with a plasmid containing si-Beclin-1. (E) QBC939 cells were treated with 3MA for 1 h, then cells were incubated with 5FU or CDDP as previously described. Morphological changes were detected by inverted phase contrast microscopy. Representative images are presented. (F) Nuclei were visualized with DAPI staining following treatment of the cells with 3MA with or without 5FU or CDDP in each condition. Representative images are presented. Arrows indicate apoptotic bodies. (G) QBC939 and RBE cells were treated with 3MA then incubated with 5FU or CDDP, as previously described. Cell viability was determined by a CCK-8 assay. The viability of the untreated cells was regarded as 100%. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of ≥3 independent experiments. *P<0.05, compared with the FN and NF groups. FN, full-nutrient; NF, nutrient-free; 5FU, 5-fluorouracil (120 µg/ml); CDDP, cisplatin (8 µg/ml); CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; SD, standard deviation; 3MA, 3-methyladenine (10 mM); DAPI, 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride; si-Beclin-1, small interfering RNA against Beclin-1.

To determine whether the inhibition of autophagy enhanced the chemosensitivity of cholangiocarcinoma cells, QBC939 cells were cultured in FN or NF media, treated with autophagy inhibitor 3MA and observed for morphological changes with a phase contrast microscope. A marked increase in cell death was observed in the nutrient-deprived group. The dead cells showed typical apoptotic changes, including marked rounding, shrinkage and detachment from the culture dish (Fig. 2B). Similar effects were further confirmed by DAPI staining, which facilitated the visualization of apoptotic bodies in the 3MA-treated and nutrient-deprived cells (Fig. 2C). Additionally, a CCK-8 assay revealed that the death rate increased following 3MA and Beclin-1-siRNA treatment in nutrient-deprived conditions (Fig. 2D).

QBC939 cells were treated with 3MA for 1 h and then incubated with 5FU or cisplatin for 12 h. The rate of cell death was significantly increased in the combination groups (3MA plus CDDP or 5FU), compared with the 5FU or CDDP group, as assessed by cell morphology (Fig. 2E), DAPI staining (Fig. 2F) or CCK-8 assay (Fig. 2G; P<0.05). These results suggest that the inhibition of autophagy contributed to the increased chemosensitivity of cholangiocarcinoma cells during nutrient deprivation.

p53 activates autophagy in cholangiocarcinoma cells in nutrient-deprived environments

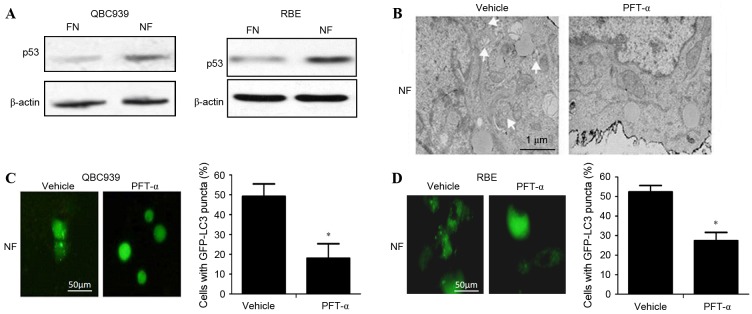

To determine whether p53 activated autophagy in cholangiocarcinoma cells in nutrient-deprived conditions, the expression level of p53 in cholangiocarcinoma cells cultured in FN and NF media was investigated. The level of p53 protein in the NF groups was significantly increased compared with the FN groups (P<0.05; Fig. 3A). Following administration of the p53-inhibitor PFT-α, the activation of autophagy was decreased in nutrient-deprived cholangiocarcinoma cells as indicated by a significant decrease in the numbers of visible autophagosomes on TEM (Fig. 3B) and GFP-LC3 puncta on fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 3C and D; P<0.01). Taken together, these data suggest that p53 can activate autophagy in cholangiocarcinoma cells in nutrient-deprived conditions.

Figure 3.

p53 activated autophagy in cholangiocarcinoma cells during nutrient deprivation. QBC939 and RBE cells were cultured in FN or NF medium with or without treatment with PFT-α. (A) Whole cell lysates from QBC939 or RBE cells were subjected to western blotting to analyze p53 levels. β-actin is included as a loading control. (B) Representative electron microscopic images are presented for QBC939 cells. Arrows indicate autophagosomes. (C) QBC939 and (D) RBE cells were transfected with GFP-LC3 plasmids and fluorescence of GFP-LC3 was evaluated by fluorescence microscopy. Representative images are presented (scale bar, 50 µm). The percentage of the GFP-LC3-positive cells that exhibited punctate GFP-LC3 fluorescence was evaluated; cells with >2 autophagosomes per cell were scored as exhibiting an autophagic reaction. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of ≥3 independent experiments. *P<0.01 vs. vehicle-treated group. FN, full-nutrient; NF, nutrient-free; PFT-α, pifithrin-α (20 µM); GFP-LC3, green fluorescent protein-tagged microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3.

Inhibition of p53 enhances chemosensitivity in cholangiocarcinoma cells during nutrient deprivation

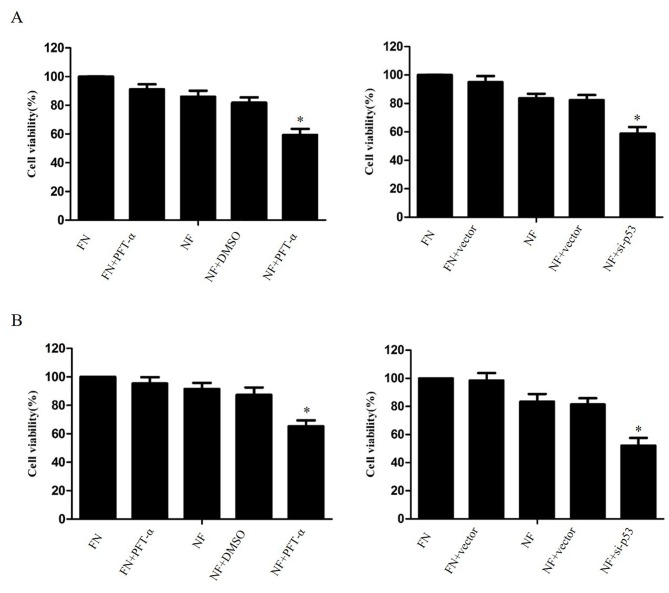

The effect of p53 inhibition on the survival of nutrient-deprived cholangiocarcinoma cells was investigated. The cell lines QBC939 and RBE were treated with 20 µM PFT-α or transfected with p53-siRNA (6231; Cell Signaling Technology, USA), then cultured for 24 h in FN or NF medium. A CCK-8 assay revealed that the suppression of p53 significantly increased the cell death rate of cholangiocarcinoma cells in nutrient-deprived conditions, compared with DMSO-treated NF cells (P<0.05; Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Inhibition of p53 enhanced cholangiocarcinoma cell death in nutrient deprived conditions. (A) QBC939 cells and (B) RBE cells were treated with PFT-α for 1 h or transfected with plasmids containing siRNA against p53, then cultured for 24 h in FN or NF medium. Cell viability was determined by a Cell Counting Kit-8 assay. The viability of the untreated cells was regarded as 100%. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of ≥3 independent experiments. *P<0.05, compared with the FN and NF groups. PFT-α, pifithrin-α (20 µM); FN, full-nutrient; NF, nutrient-free.

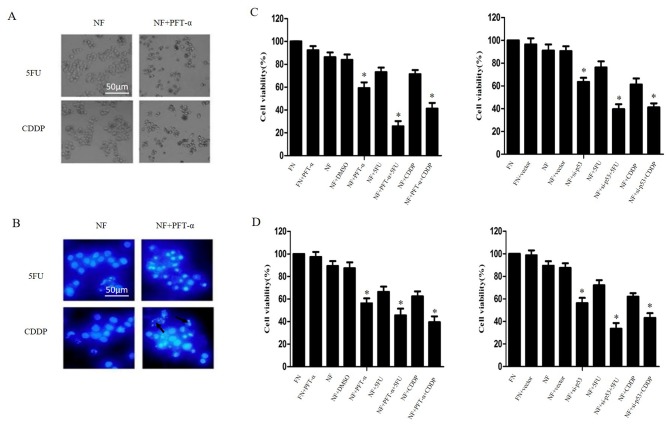

QBC939 cells were treated with 20 µM PFT-α for 1 h and then cultured in NF medium combined with 5FU or cisplatin for 24 h. As shown in Fig. 5A and B, cell-death morphology increased markedly when PFT-α was combined with 5FU or cisplatin in nutrient-deprived conditions compared with cells treated only with 5FU or cisplatin. This result was confirmed by CCK-8 assays (P<0.05; Fig. 5C and D). Taken together, these results indicate that p53 inhibition may increase the chemosensitivity of cholangiocarcinoma cells during nutrient deprivation.

Figure 5.

Inhibition of p53 enhanced chemosensitivity in cholangiocarcinoma cells in nutrient deprived conditions. QBC939 and RBE cells were treated with PFT-α for 1 h or transfected with plasmids containing siRNA against p53, then cultured in NF or FN media with 5FU or CDDP treatment for 24 h. (A) QBC939 cell morphology was detected by inverted phase contrast microscope. Representative images are presented. (B) QBC939 cell nuclei were visualized with DAPI staining. Representative images are presented. Arrows indicate apoptotic bodies. The viability of (C) QBC939 and (D) RBE cells was determined by Cell Counting Kit-8 assay. The viability of the untreated cells was regarded as 100%. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of ≥3 independent experiments. *P<0.05, compared with the FN and NF groups. PFT-α, 20 µM of pifithrin-α; siRNA, small interfering RNA; NF, nutrient-free; FN, full-nutrient; 5FU, 5-fluorouracil (120 µg/ml); CDDP, cisplatin (8 µg/ml); DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride.

Discussion

Autophagy is one of the crucial catabolic reactions of cells to stimulation or stress (15). Previous studies have demonstrated that p53 serves a complicated role in autophagy (16–18). In the present study, the results indicated that p53 is associated with the induction of autophagy during nutrient deprivation; inhibition of p53 was observed to result in the deactivation of autophagy and increased chemosensitivity in nutrient-deprived cholangiocarcinoma cells.

The effect of p53, a well-studied tumor suppressor, on autophagy is controversial (16). In the present study, it was demonstrated that the level of p53 was increased in cholangiocarcinoma cells in nutrient-deprived conditions; autophagy induced by nutrient deprivation was inhibited by PFT-α, a p53 suppressor, demonstrating the importance of p53 to the activation of autophagy in nutrient-deprived cholangiocarcinoma cells. These data are consistent with a previous study that demonstrated that p53 regulates the autophagy protein LC3 in order to mediate cancer cell survival during prolonged starvation (17).

A number of studies have shown that autophagy contributes to chemoresistance and that the inhibition of autophagy enhances chemosensitivity in cancer cells (19–21). However, these studies were performed in environments with nutrient availability. In normal conditions during tumor development, ischemic or innutritious environments are ubiquitous. The effect of inhibited autophagy on the efficacy of chemotherapy during nutrient-deprived conditions remains unclear. In the present study, it was demonstrated that the inhibition of p53 contributes to the inhibition of autophagy and an increased chemotherapy-induced cell death rate in nutrient-deprived cholangiocarcinoma cells; this indicates that autophagy is responsible for chemoresistance in cholangiocarcinoma cells during nutrient-deprivation. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of only a small number of reports that inhibition of p53 led to increased chemosensitivity.

Under normal circumstances, cells sustain a certain level of autophagy in order to maintain cellular homeostasis. When cells are confronted with adverse conditions, including nutrient deprivation, autophagy is activated to facilitate cell survival (22). Factors that affect the autophagic process are of crucial importance in managing a variation in condition. Studies by our group have shown that the inhibition of autophagy increases chemosensitivity in nutrient-deprived carcinoma cells (18). Therefore, it is hypothesized that p53 inhibition may increase cell death in conditions where autophagy is serving an important role in cell survival.

In certain conditions, particularly where apoptosis is inhibited, autophagy contributes to chemotherapy-induced cell death, and the strict definition of autophagic cell death needs to conform to specific requirements (23). Furthermore, the difference between ‘autophagic cell death’ and ‘autophagy with cell death’ remains controversial (24). It has become clear that the effect of autophagy is not only to promote cell death; it may also protect cells by allowing them to adapt to adverse conditions (25). Emerging evidence has indicated that autophagy is addictive in certain types of Ras-driven tumors (26). Autophagy is also known as type II-programmed cell death and the relationship between autophagy and apoptosis is as yet inconclusive; it may take the form of interdependence or interconversion under certain conditions.

In the present study, the morphology of the cells was observed under the fluorescence microscope following DAPI staining, and morphological changes to the nuclei could be observed. The results demonstrated that the inhibition of autophagy could increase the chemosensitivity of cholangiocarcinoma cells and increase the rate of tumor cell death, and that the mechanism for cell death was apoptosis. In this circumstance, inhibition of autophagy is a feasible therapeutic approach. The data suggest that cholangiocarcinoma cells may gain tolerance to chemotherapy through the activation of autophagy. Accordingly, inhibiting autophagy could be a novel method to improve the efficiency of traditional chemotherapies. However, autophagy-targeting strategies for cancer will require additional clinical trial testing before they can be fully realized.

In conclusion, the data reveals that p53 contributes to cell survival in nutrient-deprived conditions and that the inhibition of p53 increases the chemosensitivity of cholangiocarcinoma cells. Although mutations to p53 are detected in up to 50% of all human tumors (27,28), the remainder of tumors maintain the expression of wild-type p53. This implies that tumor cell survival may benefit from the functional status of p53 in specific situations (17). In response to minor stress, p53 could facilitate cellular homeostasis (29,30). Although p53 is better known for its role in the induction of apoptosis, further study by our group may contribute to expanding the understanding of the effect of p53 on cancer therapy. These results elucidate the role of autophagy in cancer formation and progression. Further studies on the molecular mechanism by which autophagy promotes chemoresistance should be considered, and may contribute to the development of therapy against cholangiocarcinoma or other types of cancer.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- 3MA

3-methyladenine

- 5FU

5-fluorouracil

- CCK-8

Cell Counting Kit-8

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- EBSS

Earle's balanced salt solution

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- LC3

microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3

- PFT-α

pifithrin-α

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

References

- 1.Lin WJ, Kuang HY. Oxidative stress induces autophagy in response to multiple noxious stimuli in retinal ganglion cells. Autophagy. 2014;10:1692–1701. doi: 10.4161/auto.36076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White E, Mehnert JM, Chan CS. Autophagy, metabolism and cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:5037–5046. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hale AN, Ledbetter DJ, Gawriluk TR, Rucker EB., III Autophagy: Regulation and role in development. Autophagy. 2013;9:951–972. doi: 10.4161/auto.24273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Livesey KM, Tang D, Zeh HJ, Lotze MT. Autophagy inhibition in combination cancer treatment. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;10:1269–1279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ávalos Y, Canales J, Bravo-Sagua R, Criollo A, Lavandero S, Quest AF. Tumor suppression and promotion by autophagy. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:603980. doi: 10.1155/2014/603980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang J, Di J, Cao H, Bai J, Zheng J. p53-mediated autophagic regulation: A prospective strategy for cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2015;363:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White EJ, Martin V, Liu JL, Klein SR, Piya S, Gomez-Manzano C, Fueyo J, Jiang H. Autophagy regulation in cancer development and therapy. Am J Cancer Res. 2011;1:362–372. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borodkina AV, Shatrova AN, Deryabin PI, Grukova AA, Nikolsky NN, Burova EB. Tetraploidization or autophagy: The ultimate fate of senescent human endometrial stem cells under ATM or p53 inhibition. Cell Cycle. 2016;15:117–127. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2015.1121326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levine AJ, Oren M. The first 30 years of p53: Growing ever more complex. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:749–758. doi: 10.1038/nrc2723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexandrova EM, Marchenko ND. Mutant p53 - heat shock response oncogenic cooperation: A new mechanism of cancer cell survival. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2015;6:53. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2015.00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun HW, Tang QB, Tang C, Zou SQ. Effects of dendritic cells transfected with full length wild-type p53 and modified by bile duct cancer lysates on immune response. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2005;4:121–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Z, Tang X, Zhang Y, Qi R, Li Z, Zhang K, Liu Z, Yang X. Lobaplatin induces apoptosis and arrests cell cycle progression in human cholangiocarcinoma cell line RBE. Biomed Pharmacother. 2012;66:161–166. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takasu H, Sugita A, Uchiyama Y, Katagiri N, Okazaki M, Ogata E, Ikeda K. c-Fos protein as a target of anti-osteoclastogenic action of vitamin D, and synthesis of new analogs. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:528–535. doi: 10.1172/JCI24742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song J, Qu Z, Guo X, Zhao Q, Zhao X, Gao L, Sun K, Shen F, Wu M, Wei L. Hypoxia-induced autophagy contributes to the chemoresistance of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Autophagy. 2009;5:1131–1144. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.8.9996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parkhitko AA, Favorova OO, Henske EP. Autophagy: Mechanisms, regulation, and its role in tumorigenesis. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2013;78:355–367. doi: 10.1134/S0006297913040044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maiuri MC, Galluzzi L, Morselli E, Kepp O, Malik SA, Kroemer G. Autophagy regulation by p53. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:181–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scherz-Shouval R, Weidberg H, Gonen C, Wilder S, Elazar Z, Oren M. p53-dependent regulation of autophagy protein LC3 supports cancer cell survival under prolonged starvation; Proc Natl Acad Sci USA; 2010; pp. 18511–18516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo XL, Hu F, Zhang SS, Zhao QD, Zong C, Ye F, Guo SW, Zhang JW, Li R, Wu MC, Wei LX. Inhibition of p53 increases chemosensitivity to 5-FU in nutrient-deprived hepatocarcinoma cells by suppressing autophagy. Cancer Lett. 2014;346:278–284. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ji MM, Wang L, Zhan Q, Xue W, Zhao Y, Zhao X, Xu PP, Shen Y, Liu H, Janin A, et al. Induction of autophagy by valproic acid enhanced lymphoma cell chemosensitivity through HDAC-independent and IP3-mediated PRKAA activation. Autophagy. 2015;11:2160–2171. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1082024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan Y, Gao Y, Chen L, Gao G, Dong H, Yang Y, Dong B, Chen X. Targeting autophagy augments in vitro and in vivo antimyeloma activity of DNA-damaging chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:3248–3258. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo XL, Li D, Hu F, Song JR, Zhang SS, Deng WJ, Sun K, Zhao QD, Xie XQ, Song YJ, et al. Targeting autophagy potentiates chemotherapy-induced apoptosis and proliferation inhibition in hepatocarcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2012;320:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Russell RC, Yuan HX, Guan KL. Autophagy regulation by nutrient signaling. Cell Res. 2014;24:42–57. doi: 10.1038/cr.2013.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiong HY, Guo XL, Bu XX, Zhang SS, Ma NN, Song JR, Hu F, Tao SF, Sun K, Li R, et al. Autophagic cell death induced by 5-FU in Bax or PUMA deficient human colon cancer cell. Cancer Lett. 2010;288:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroemer G, Levine B. Autophagic cell death: The story of a misnomer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:1004–1010. doi: 10.1038/nrm2529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen S, Kepp O, Kroemer G. The end of autophagic cell death? Autophagy. 2012;8:1–3. doi: 10.4161/auto.8.1.16618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mancias JD, Kimmelman AC. Targeting autophagy addiction in cancer. Oncotarget. 2011;2:1302–1306. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaughan C, Pearsall I, Yeudall A, Deb SP, Deb S. p53: Its mutations and their impact on transcription. Subcell Biochem. 2014;85:71–90. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-9211-0_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muller PA, Vousden KH. Mutant p53 in cancer: New functions and therapeutic opportunities. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:304–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chao CC. Mechanisms of p53 degradation. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;438:139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2014.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu J, Zhang C, Hu W, Feng Z. Tumor suppressor p53 and its mutants in cancer metabolism. Cancer Lett. 2015;356:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]