Abstract

Objectives

Smoking has been connected to citrullination of antigens and formation of anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies (ACPAs) in rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Since smoking can modify proteins by carbamylation (formation of homocitrulline), this study was conducted to investigate these effects on vimentin in animal models and RA.

Methods

The efficiency of enzymatic carbamylation of vimentin was characterised. B-cell response was investigated after immunisation of rabbits with different vimentin isoforms. Effects of tobacco smoke exposure on carbamylation of vimentin and formation of autoantibodies were analysed in mice. The antibody responses against isoforms of vimentin were characterised with respect to disease duration and smoking status of patients with RA.

Results

Enzymatic carbamylation of vimentin was efficiently achieved. Subsequent citrullination of vimentin was not disturbed by homocitrullination. Sera from rabbits immunised with carbamylated vimentin (carbVim), in addition to carbVim also recognised human IgG-Fc showing rheumatoid factor-like reactivity. Smoke-exposed mice contained detectable amounts of carbVim and developed a broad immune response against carbamylated antigens. Although the prevalence of anti-carbamylated antibodies in smokers and non-smokers was similar, the titres of carbamylated antibodies were significantly increased in sera of smoking compared with non-smoking RA. CarbVim antibodies were observed independently of ACPAs in early phases of disease and double-positive patients for anti-mutated citrullinated vimentin (MCV) and anti-carbVim antibodies showed an extended epitope recognition pattern towards MCV.

Conclusions

Carbamylation of vimentin is inducible by cigarette smoke exposure. The polyclonal immune response against modified antigens in patients with RA is not exclusively citrulline-specific and carbamylation of antigens could be involved in the pathogenesis of disease.

Trial registration number

ISRCTN36745608; EudraCT Number: 2006-003146-41.

Keywords: Smoking, DAS28, Rheumatoid Arthritis

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune disease in genetically prone individuals where multiple environmental factors can induce the inflammatory process.1 Interestingly, the specific autoimmune response is directed against a number of different antigens modified by post-translational modifications (PTMs).2 In this context, enzymatic deimination of peptide-bound arginine to citrulline by peptidylarginine deiminases (PADs) is considered as a key mechanism.3 Studies in different cohorts of RA have revealed that tobacco exposure increases the risk of anti-citrullinated protein/peptide antibodies (ACPAs) formation, especially in carriers of the shared epitope.1 4

Another PTM that has been connected to smoking is carbamylation of lysine, creating a homologous citrulline structure that is extended by a single carbon residual, also known as homocitrulline.5 Various carbamylations are formed by the interaction of isocyanate (HNCO) with α-amino and ε-amino groups of proteins, among them, α-carbamylation, when α-amino groups of amino acids are involved, and ε-carbamylation, which is formed by the interaction of isocyanate with the ε-amino group of lysine.6

In humans, isocyanate is formed by the decomposition of urea into ammonia and cyanate, which is transformed to isocyanate. Thus, uraemia secondary to renal diseases is a pathological state that leads to the formation of isocyanate.7

The second key reactant for isocyanate formation is thiocyanate (SCN−), a metabolite of cyanide that is present in cigarette smoke. Thiocyanate increases in urine, serum and saliva with the amount of cigarette smoke.8 Moreover, passive exposure to smoke significantly increased thiocyanate levels when compared with non-exposure.9 Neutrophil myeloperoxidase (MPO) represents a marker of inflammation and is significantly higher in smokers than non-smokers.10 It uses H2O2 to oxidise thiocyanate to cyanate that subsequently promotes protein carbamylation at sites of inflammation.11

Mice immunised with carbamylated proteins (carbP) developed arthritis and a T-cell response against corresponding antigens. Additionally, antibodies against carbP but not ACPAs were detectable in mice with collagen-induced arthritis.12 13 It was also demonstrated that sera from patients with RA contain different antibody specificities recognising either citrulline-containing or homocitrulline-containing antigens,14 15 and that anti-carbP as well as ACPAs are detectable even before the onset of symptoms of RA.16 These findings suggest that in addition to citrullination, carbamylation represents another crucial process in the pathogenesis of RA.17

Accumulating evidence suggests an involvement of modified vimentin and anti-modified vimentin antibodies in the pathogenesis of RA.18 19 Vimentin is one of the most widely expressed mammalian intermediate filament proteins. The vimentin network that extends from the nucleus to the plasma membrane is believed to act as a scaffold, providing cellular mechanostructural support and thereby maintaining cell and tissue integrity.20 Therefore, we hypothesised that vimentin could serve as a substrate for carbamylation from smoking ingredients and investigated the autoantibody response against different isoforms of vimentin in patients with RA.

Material and methods

Modification of antigens

Non-enzymatic carbamylation of vimentin was achieved by incubation of vimentin with potassium cyanate (KOCN). Incubation conditions and quantification of carbamylation were performed as recently described.21 Enzymatic carbamylation was achieved by incubation of vimentin with MPO (Arotec Diagnostics, New Zealand), according to the previously described procedures.22 As we described recently,21 incubation of recombinant vimentin with KOCN achieved approximately 80% carbamylation.

Animals, immunisation and antibodies

Chicken and rabbit antibodies directed against citrullinated vimentin (citrVim) or carbamylated vimentin (carbVim) were produced by Davids Biotechnology (Regensburg, Germany). New Zealand white rabbits were immunised subcutaneously with 30 µg of peptide emulsified in adjuvant addavax, an MF59-like nanoemulsion; the injections were performed every 14 days for five times. Rabbit polyclonal IgG anti-vimentin antibodies (H-84, Santa Cruz) were employed as reference. To isolate specific antibodies, a previously described procedure for affinity purification was used23 (see online supplementary methods).

annrheumdis-2016-210059supp001.pdf (281.3KB, pdf)

Cell fractions as source for modification of antigens

To clarify whether a preferential carbamylation of certain proteins occurs, HeLa cell extracts were used for cell fractionation. Modified and untreated fractions were used to identify specificity of different sera (see online supplementary methods).

Smoke-exposed mice

For mouse experiments, a whole-body smoking chamber (Teague TE-10) was used as described.24 Mice (C57BL/6) were exposed to tobacco smoke for 6 hours over 5 days weekly for 3 weeks. Control mice breathed filtered air.

Serum samples of the respective mice were investigated for soluble, modified vimentin by using albumin/immunoglobulin depletion columns. Subsequently, the throughput was depleted with trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and separated by 12.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Detection of modified vimentin was performed with an antibody specific for carbVim. After washing of the separation columns, the eluate from two mice served as controls.

To detect antibodies with different recognition pattern, modified and untreated HeLa cell fractions together with aliquots of unmodified vimentin, citrVim and carbVim were separated by SDS-PAGE and used for immunoblotting with the indicated sera.

ELISA was used to investigate the concentration of anti-carbVim in sera of smoking and control mice.

Immunoblotting using sera from patients with RA

Vimentin, citrVim and carbVim were used to detect the presence of antibodies in sera of patients with RA by immunoblotting.

Detection of rheumatoid factor IgM and anti- mutated citrullinated vimentin IgG antibodies by ELISA

Both antibodies were measured using commercially available ELISA kits (Orgentec Diagnostika, Germany).

Modification specificity of RA autoantibodies and epitope pattern analysis

The predominant vimentin epitope NH2-GGVYATRSSAVR-OH was used to synthesise modified vimentin peptide, citrVim P18 or homocitrulline (carbVim) HC52 (see online supplementary table S1). Both post-translationally modified vimentin peptides were used in ELISA as described,21 25 Carbamylated vimentin protein was also used in ELISA as described.21 Additionally, the human full-length vimentin was used to synthesise overlapping 17mer peptides of vimentin resulting in 91 peptides with the general formula ‘Biotin-SGSG-PEPTIDE-Amide’.23

Patients

Sera from patients with RA fulfilling the 2010 American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/European League Against Rheumatism criteria (early disease with duration <12 months n=22 and established disease n=28) in addition to 10 healthy donors (HDs) were used for immunoblot experiments and for the analysis of the epitope recognition pattern of patient subgroups regarding the presence of the different autoantibodies. All established patients with RA were treated with conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (cDMARDs) and four received biological DMARDs (three etanercept and one adalimumab) in combination with cDMARDs. Only two patients with early RA received cDMARDs. A total of 41 patients (15 with Sjögren's syndrome and 26 with systemic lupus erythematosus) in addition to 39 HDs served as control group to calculate sensitivity and specificity of vimentin peptides. All samples were obtained from patients at the Department of Rheumatology and Clinical Immunology, Charité-Universitätsmedizin, Berlin, Germany, after approval by the local ethics committee.

For ELISA, all patients were recruited from the double-blind, randomised controlled trial HIT HARD.26 All patients (n=172) with recent onset (≤1 year) RA were diagnosed according to the revised 1987 ACR criteria for the classification of RA. Depending on the smoking status, patients were classified as current smokers (n=42), non-smokers (n=68) or ex-smokers (n=34). At week 24, 118 responders and 12 non-responders were identified using the disease activity score 28 erythrocyte sedimentation rate (DAS28ESR) at baseline and week 24 and defined as an improvement of ≥1.2.

Statistical analysis

GraphPad Prism (V.4.0) and SPSS (V.19.0) software were used for statistics. χ2 test was used for association analyses between smoking and seropositivity of subtype IgG of citrullinated, carbamylated and mutated citrullinated vimentin (MCV) antibodies. ORs were calculated. The paired sample sign test was used to evaluate the differences of antibody titres from baseline to week 24 and week 48. Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare antibody titres between different groups. Correlation analyses were performed using Spearman's rank correlation test (rs). p Values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Kinetics of vimentin modification and specificity of antibody responses

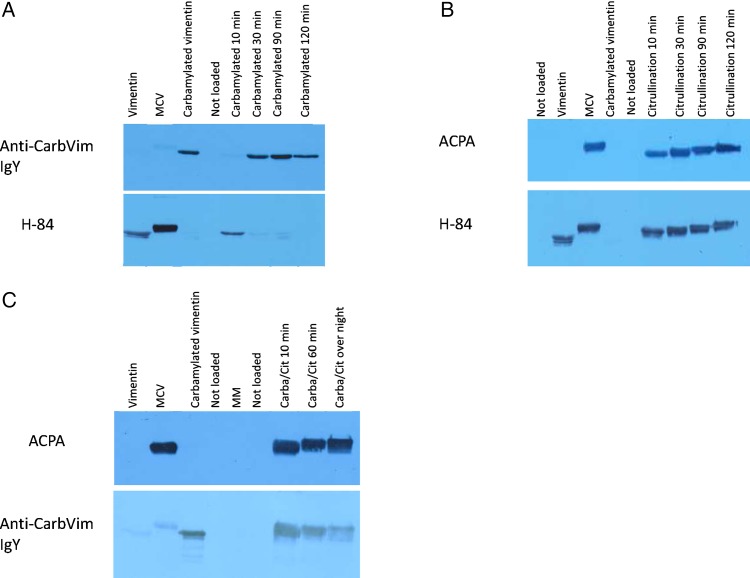

To test a possible link between inflammation and tobacco smoking, we used the MPO/H2O2/SCN− system. The amount and quality of homocitrullination of MPO-exposed vimentin was confirmed by immunoblotting using the specific anti-carbVim antibodies (anti-carbVim IgY).

As shown in figure 1A, the anti-carbVim IgY antibodies were specific for carbVim and detected the modified antigen when the reaction lasted for at least 30 min. Anti-vimentin antibodies (H-84) verified the modification of lysine residues by showing a loss of reactivity due to a change of antigenic epitopes after 30 min of antigen treatment. These results indicate that a peroxidase-supported modification system can serve as an alternative tool for homocitrullination. For comparison, detection of citrVim is shown in figure 1B by using anti-vimentin antibodies and affinity-purified human ACPAs. This modification is very efficient and the sequential enzymatic reaction occurs faster than homocitrullination of vimentin in <10 min.

Figure 1.

Images showing the rapid citrullination and carbamylation of vimentin under optimal conditions detected by immunoblotting. Induction of both citrullination and carbamylation generates relevant amounts of antigen after 30 min of exposure. Citrullination can occur after carbamylation without affecting antigenic properties. (A) Upper lane: Confirmation of carbamylation using a specific serum. Lower lane: Control with commercial H-84 antibodies, which shows a reduced signal against vimentin after 10 min and disappearance after 30 min due to complete conversion. (B) Upper lane: Confirmation of citrullination using a positive anti-citrullinated peptide antibody (ACPA) serum from a patient with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Lower lane: Control with commercial H-84 antibodies, which shows reactivities against vimentin as well as against citrullinated isoforms of vimentin. (C) Upper lane: Confirmation of citrullination after carbamylation using a positive ACPA serum from a patient with RA. Lower lane: Confirmation of carbamylation using specific serum. CarbVim, carbamylated vimentin; MCV, mutated citrullinated vimentin; MM, molecular weight marker.

To monitor if carbamylation antagonises arginine deamination (citrullination) or vice versa, both reactions were accomplished sequentially. The respective results are shown in figure 1C demonstrating that the capacity of PAD to deiminate all arginine residues of vimentin is not influenced by the chemical carbamylation, which indicates that in vivo both processes could take place in parallel or in sequential manner.

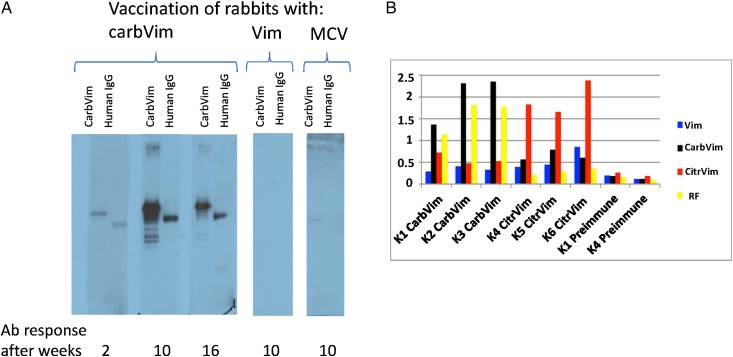

Different immunogenicity of vimentin isoforms

Rabbits were immunised with vimentin as well as with the citrulline-containing and homocitrulline-containing isoforms and tested for cross-reactivity to carbVim and human IgG-Fc in immunoblots. Immunisation with carbVim induced antibody reactivities against both carbVim and human IgG-Fc, showing rheumatoid factor (RF)-like reactivity. In contrast, rabbits immunised with vimentin or MCV recognised neither carbVim nor human IgG-Fc (figure 2A). Using ELISA, rabbits immunised with citrVim or carbVim were investigated for the presence of cross-reactivity to vimentin, carbVim, citrVim and human IgG-Fc. Sera from rabbits immunised with either citrVim or carbVim showed strong antibody positive bindings specifically to their corresponding induced antigens. In addition to the presence of weak cross-reactivity in both cases, anti-human IgG-Fc reactivity was only observed in homocitrulline-immunised rabbits (figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Representations showing the development of antibody after immunisation of rabbits with carbamylated vimentin (carbVim). (A) Kinetics of antibody development after immunisation of rabbits with carbVim, vimentin and mutated citrullinated vimentin (MCV). Only immunisations with carbVim induced the formation of anti-carbVim antibodies. Human IgG-Fc from serum samples of healthy controls was isolated employing protein-A-affinity chromatography, separated under denatured conditions in SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane for immunoblotting. IgG heavy chains were recognised by rabbit serum immunised with carbVim. (B) Differences in antibody specificities (profiles) after immunisation of rabbits with either carbVim (K1-3) or citrullinated vimentin (citrVim) (K4-6). Rabbits were immunised with 20 µg of the indicated antigen in Freund's complete adjuvant. Sera from the indicated animals were 1:200 diluted and analysed with the indicated antigens using enzyme immune assay (observed optical absorption are shown from a representative assay). RF, rheumatoid factor.

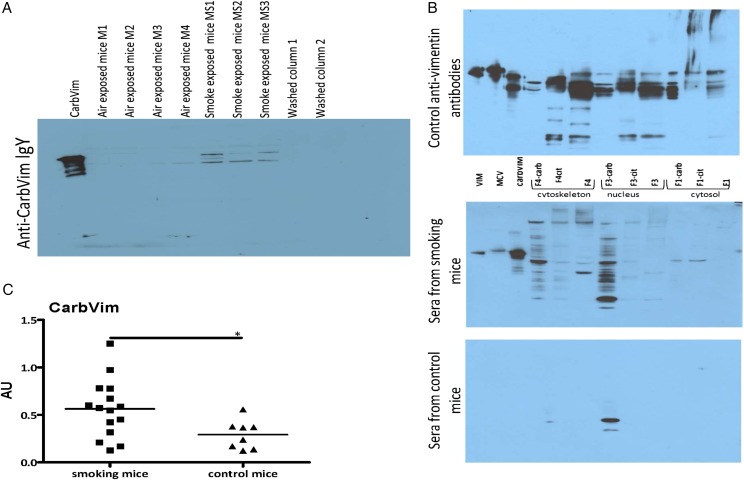

Tobacco exposure to mice induced carbamylation of antigens and antibody response

Sera of smoking mice contained increased amounts of carbVim in comparison with control animals (figure 3A). Smoking mice also generated antibodies with different specificities against carbPs (figure 3B). Additionally, the concentration of anti-carbVim antibodies was significantly increased in sera of smoke-exposed mice compared with controls (figure 3C). However, during an observation period of 3 weeks, no manifestation of an inflammatory joint disease could be observed.

Figure 3.

Representations showing carbamylated vimentin (carbVim) and antibodies against carbamylated antigens detectable in mouse sera after smoke exposure. (A) Serum samples derived from mice exposed to smoke contained detectable amounts of carbVim using anti-carb IgY in immunoblotting. Of note, the observed differences in the SDS-PAGE are well-known phenomena for the different isoforms of vimentin depending on their degree of citrullination and phosphorylation. (B) Antibodies with different recognition patterns to carbamylated proteins are detectable in sera of mice exposed to tobacco smoke. Aliquots of unmodified, citrullinated vimentin or carbVim together with modified and untreated HeLa cell fractions (F1 cytosolic proteins, F3 nucleic proteins and F4 components of the cytoskeleton) were subjected to SDS-PAGE (4%–12% NuPAGE, Invitrogen) for immunoblotting with the indicated sera and anti-vimentin antibodies as a reference. (C) Levels of anti-carbVim antibodies in sera of smoke exposed and control mice are shown. Mean of titres was shown. Mann-Whitney U test was used and statistical significance is indicated for p<0.05 (*). MCV, mutated citrullinated vimentin.

Immunoblotting and epitope recognition patterns of sera from patients with RA

To clarify whether antibodies against carbVim are detectable in patients with early RA and whether they form an own class distinguishable from ACPAs, the respective isoforms were investigated by immunoblotting and ELISA. Immunoblot showed that patients with RA in all stages of disease expressed reactivities against either citrVim, carbVim or both isoforms of vimentin (see online supplementary figure S1).

To characterise the epitope recognition pattern of patient subgroups with respect to the occurrence of the different autoantibodies, overlapping citrullinated peptides resembling the sequence of vimentin were used. Sera from ACPA and/or anti-homocitrulline-positive patients in comparison with HDs (n=10 per group) were investigated using ELISA. An extended recognition pattern was characteristic for patients with both antibody subtypes (anti-carbVim and MCV antibodies, see online supplementary figure S2C), in comparison with a more restricted epitope repertoire of sera containing only antibodies against MCV (see online supplementary figure S2A). Of note, patients with positive bindings to carbVim also showed cross-reactivity with linear citrullinated peptides indicating that their specificity to the full length modified antigen is provided by conformational epitopes (see online supplementary figure S2B). HDs showed negative reactivity (see online supplementary figure S2D). All tested sera of patients with RA showed negative reactivity against unmodified peptide of vimentin.

IgG antibody patterns of patients with RA (HIT HARD) against citrullinated (P18) and carbamylated (HC52) peptides of vimentin using ELISA

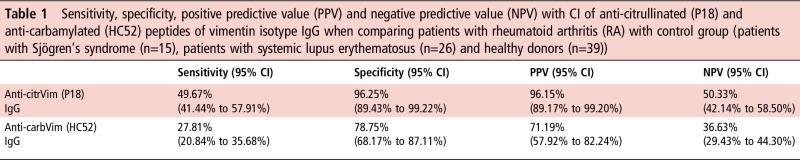

Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values of these antibodies were calculated to evaluate their efficiency in predicting RA development (table 1).

Table 1.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) with CI of anti-citrullinated (P18) and anti-carbamylated (HC52) peptides of vimentin isotype IgG when comparing patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) with control group (patients with Sjögren's syndrome (n=15), patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (n=26) and healthy donors (n=39))

|

carbVim, carbamylated vimentin; citrVim, citrullinated vimentin.

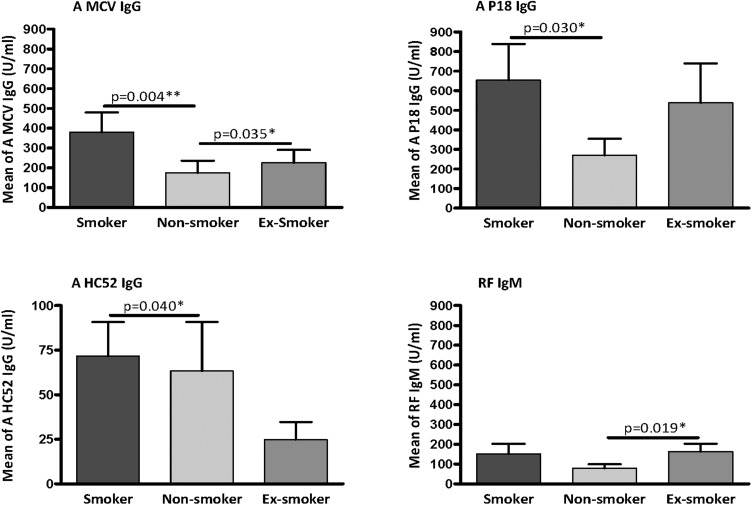

We compared the titre of carbVim antibodies between different patient groups with RA classified according to smoking habit. The titre of anti-carbVim IgG antibodies was significantly higher in smokers compared with non-smokers. Furthermore, both citrVim and MCV IgG antibodies showed significantly increased titres in smokers compared with non-smokers (figure 4). However, analyses of the prevalence of positivity for each antibody in smokers and non-smokers showed no association between smoking and the presence of anti-carbVim IgG (χ2 p=0.229, OR=1.667, 95% CI 0.722 to 3.848). In contrast, the presence of anti-citrullinated peptide IgG (χ2 p=0.018, OR=2.571, 95% CI 1.161 to 5.694) and anti-MCV IgG (χ2 p=0.005, OR=3.096, 95% CI 1.390 to 6.898) was clearly associated with smoking habit.

Figure 4.

Plots showing the autoantibody levels in sera of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) classified according to the smoking status. Comparison of autoantibody reactivities of anti-mutated citrullinated vimentin IgG (A MCV IgG), anti-citrullinated peptide of vimentin IgG (A P18 IgG), anti-carbamylated peptide of vimentin IgG (A HC52 IgG) and rheumatoid factor (RF) IgM in sera of patients with early onset RA having known smoking status. Smokers (n=42), non-smokers (n=68) and ex-smokers (n=34). Cut-off was identified as 20 U/mL. Values of mean with SEM are shown. Mann-Whitney U test was used and statistical significance is indicated for p<0.05 (*) and p<0.01 (**).

Analysis of the coincidence of anti-P18 and anti- HC52 IgG antibodies with anti-MCV IgG showed that 55.55% of smokers who showed positivity for anti-MCV IgG were also positive for anti-carbamylated antibodies (χ2 p=0.0003, OR=38.44, 95% CI 2.086 to 708.3); this percentage declined to 48% in non-smokers (χ2 p=0.0008, OR=7.015, 95% CI 2.073 to 23.74) (see online supplementary table S2).

The prevalence of anticarbamylated IgG antibodies in patients with RA was lower (28%) compared with anti-MCV IgG, anti-citrullinated peptide IgG and RF IgM (48.3%, 50% and 46%, respectively). However, the concentration of both anti-carbamylated and anti-citrullinated peptide IgG antibodies correlated well with anti-MCV IgG in all patients (rs=0.72, 0.81, respectively, p<0.0001 for both). This effect was stronger in smokers (rs=0.82, 0.81, respectively, p <0.0001 for both) compared with non-smokers (rs=0.64, 0.76, respectively, p<0.0001 for both). Correlation between anti-MCV IgG and RF IgM in all patients was weak (rs=0.63, p <0.0001) and not restricted to smoking status.

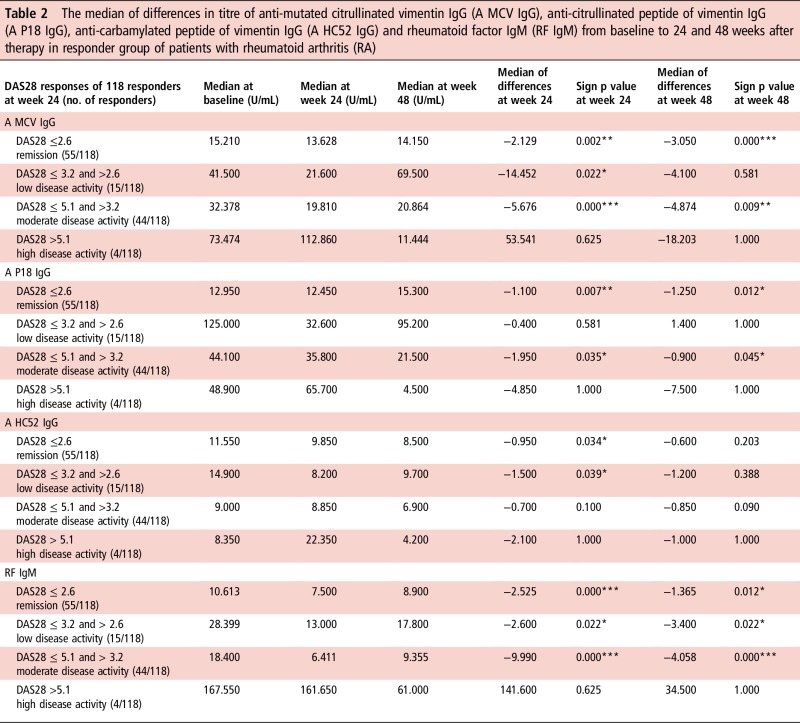

To clarify whether the titre of anti-citrullinated and anti-carbamylated IgG antibodies correlates with disease activity in patients with RA, we classified the patients into treatment responders and non-responders according to DAS28ESR. By comparing the differences from baseline to 24 and 48 weeks after therapy in both groups, the titre reduction did not reflect improved treatment response for all tested antibodies (table 2). However, at 24 and 48 weeks, a significant titre reduction of anti-MCV IgG, RF IgM and to a lesser extent of anti-citrullinated and anti-carbamylated antibodies was observed in responders with the exception of those with constant high disease activity. Due to low numbers of non-responders, no statistical evaluation was possible.

Table 2.

The median of differences in titre of anti-mutated citrullinated vimentin IgG (A MCV IgG), anti-citrullinated peptide of vimentin IgG (A P18 IgG), anti-carbamylated peptide of vimentin IgG (A HC52 IgG) and rheumatoid factor IgM (RF IgM) from baseline to 24 and 48 weeks after therapy in responder group of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

|

The analysis was done in relation to their achieved DAS28 response after 24 weeks of treatment. Paired sample sign test was used and statistical significance is indicated for p<0.05 (*), p<0.01 (**) and p<0.001 (***).

DAS28, disease activity score 28.

Notably, the therapeutic effect for induction of response and remission was affected by smoking habit; thus, whereas almost 55% of non-smokers achieved remission, only 40% of smokers and 36% of ex-smokers reached the same outcome.

Discussion

Smoking has been identified as a major risk factor for the induction and perpetuation of RA.27 The current pathogenetic model suggests citrullination of antigens in the lungs and elsewhere as a driving process.28 However, it seems that the significance of other PTMs such as carbamylation has not been recognised sufficiently so far.

In this study, we characterised the extent and the kinetics of carbamylation of vimentin as a well-known autoantigen with close association to the pathogenesis of RA. We provided clear evidence that carbVim and not citrVim is a strong antigen that induces a B-cell response against itself and against human IgG-Fc in an animal model, thus inducing a RF-like activity. Almost the whole spectrum of autoantibodies characteristic of RA was induced. Moreover, in agreement with other studies,29 30 we showed that the autoimmune response against carbVim is an early event in the pathogenesis of RA. Additionally, we proved that vimentin, as a major and well-characterised autoantigen in RA, does form its own class of carbamylated antigens that could be strongly recognised by antisera induced only with the corresponding antigen in an animal model. The cross-reactions, which have been seen in carbVim-positive RA sera as well as in antisera of rabbits immunised with carbVim, could occur in ureido group-specific manner. Furthermore, we showed that both carbamylation and citrullination are independent processes that may happen in parallel or in sequential manner.

In a mouse model, we showed that carbamylation of vimentin can be triggered by exposure to tobacco smoke and that this antigen and potentially other modified proteins are able to induce a broad immune reaction against many variants of carbP. Additionally, a significantly increased level of anti-carbamylated antibodies was observed in smoke-exposed mice and smoking patients with RA when compared with filtered air-exposed or non-smoking controls. However, in agreement with other studies,25 29 no association between smoking and anti-carbamylated antibody positivity was detected in patients with RA. These findings support the idea that carbamylation in smokers and non-smokers could be induced by additional triggering factors including even passive exposure to tobacco smoke. Nevertheless, smoking induced increased titres of carbamylated antibodies in humans and mouse models.

In our previous study on Cuban patients,21 the prevalence of IgG antibodies against carbamylated peptides of vimentin was higher (60% and almost 80% in early and established RA, respectively) than in the present study (28%). It has been shown that the combination of major histocompatibility complex, class II, DR beta 1 (HLA-DRB1)-shared epitope alleles and smoking is associated with RA susceptibility31 and different genetic associations of autoantibody-positive disease subgroups was identified in relation to the presence of DRB1*04.32 These findings suggest that the discrepancy in the frequencies of autoantibodies between different populations could be attributed to the genetic heterogeneity, as well as different environmental and behavioural factors.

Notably, the epitope recognition patterns and the coincidences of anti-carbamylated with anti-MCV antibodies suggest a strong association between these antibodies in RA. This is in agreement with a recently described association of anti-carbP and anti-citrVim that could not be explained by cross-reactivity.33

Of note, a treatment-related reduction of antibody titres was less obvious for anti-carbamylated antibodies compared with all other tested antibodies. This indicates that anti-carbamylated antibodies are produced by a distinct B-cell subset, which appears to be more treatment-resistant.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that the polyclonal immune response against modified antigens in RA is restricted to citrullinated and carbamylated autoantigens, which could be involved in the pathogenesis of disease and response to therapy. Direct or indirect exposure to tobacco smoke could have an effect by inducing carbamylation, which could trigger a pathogenic B-cell response.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Tanja Braun for her support in clinical data collection in the randomised controlled trial (RCT) HIT HARD and Annushka Wurdinger for assistance in immunoblotting.

Footnotes

Contributors: CO performed the analysis of the mouse experiments and contributed in writing and reviewing the manuscript; HB advised vimentin carbamylation, animal immunisation, HeLa cell fractionation, Western blot analysis, ELISA kits developing and contributed in writing and reviewing the manuscript; EF designed the study, collected the results and contributed in writing and reviewing the manuscript; GC and SK performed and designed the analysis of the mouse experiments and contributed in reviewing the manuscript; JD collected samples and clinical data of RCT HIT HARD and contributed in reviewing the manuscript; AK developed and performed the analysis of the ELISA kits, immunoblot experiments and contributed in reviewing the manuscript; SG contributed to the study design and in reviewing the manuscript; KG performed and designed the analysis of ELISA experiments, collected clinical data and contributed in writing and reviewing the manuscript and GRB contributed to the study design and in writing and reviewing the manuscript.

Funding: The study was supported by the FP7 HEALTH programme under the grant agreement FP7-HEALTHF2-2012-305549, HIT HARD study (German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF, grant number: 01KG0602) and EU IMI grant BeTheCure, contract no 115142-2; ArthroMark of the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF, grant number: 01EC1401A).

Competing interests: HB is an employee of Orgentec Diagnostika GmbH, Mainz, Germany; test kits were kindly provided by Orgentec.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Hensvold AH, Magnusson PK, Joshua V, et al. . Environmental and genetic factors in the development of anticitrullinated protein antibodies (ACPAs) and ACPA-positive rheumatoid arthritis: an epidemiological investigation in twins. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:375–80. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bax M, Huizinga TW, Toes RE. The pathogenic potential of autoreactive antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Immunopathol 2014;36:313–25. 10.1007/s00281-014-0429-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van Venrooij WJ, Pruijn GJ. How citrullination invaded rheumatoid arthritis research. Arthritis Res Ther 2014;16:103 10.1186/ar4458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lundberg K, Bengtsson C, Kharlamova N, et al. . Genetic and environmental determinants for disease risk in subsets of rheumatoid arthritis defined by the anticitrullinated protein/peptide antibody fine specificity profile. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:652–8. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang Z, Nicholls SJ, Rodriguez ER, et al. . Protein carbamylation links inflammation, smoking, uremia and atherogenesis. Nat Med 2007;13:1176–84. 10.1038/nm1637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jaisson S, Pietrement C, Gillery P. Carbamylation-derived products: bioactive compounds and potential biomarkers in chronic renal failure and atherosclerosis. Clin Chem 2011;57:1499–505. 10.1373/clinchem.2011.163188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kraus LM, Kraus AP Jr. Carbamylation of amino acids and proteins in uremia. Kidney Int Suppl 2001;78:S102–7. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.59780102.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zil-a-Rubab, Rahman MA. Serum thiocyanate levels in smokers, passive smokers and never smokers. J Pak Med Assoc 2006;56:323–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Husgafvel-Pursiainen K, Sorsa M, Engström K, et al. . Passive smoking at work: biochemical and biological measures of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 1987;59:337–45. 10.1007/BF00405277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Andelid K, Bake B, Rak S, et al. . Myeloperoxidase as a marker of increasing systemic inflammation in smokers without severe airway symptoms. Respir Med 2007;101:888–95. 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. van Dalen CJ, Whitehouse MW, Winterbourn CC, et al. . Thiocyanate and chloride as competing substrates for myeloperoxidase. Biochem J 1997;327 (Pt 2):487–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stoop JN, Liu BS, Shi J, et al. . Antibodies specific for carbamylated proteins precede the onset of clinical symptoms in mice with collagen induced arthritis. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e102163 10.1371/journal.pone.0102163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mydel P, Wang Z, Brisslert M, et al. . Carbamylation-dependent activation of T cells: a novel mechanism in the pathogenesis of autoimmune arthritis. J Immunol 2010;184:6882–90. 10.4049/jimmunol.1000075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shi J, Knevel R, Suwannalai P, et al. . Autoantibodies recognizing carbamylated proteins are present in sera of patients with rheumatoid arthritis and predict joint damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011;108:17372–7. 10.1073/pnas.1114465108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Scinocca M, Bell DA, Racape M, et al. . Antihomocitrullinated fibrinogen antibodies are specific to rheumatoid arthritis and frequently bind citrullinated proteins/peptides. J Rheumatol 2014;41:270–9. 10.3899/jrheum.130742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shi J, van de Stadt LA, Levarht EW, et al. . Anti-carbamylated protein (anti-CarP) antibodies precede the onset of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:780–3. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shi J, van Veelen PA, Mahler M, et al. . Carbamylation and antibodies against carbamylated proteins in autoimmunity and other pathologies. Autoimmun Rev 2014;13:225–30. 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Turesson C, Mathsson L, Jacobsson LT, et al. . Antibodies to modified citrullinated vimentin are associated with severe extra-articular manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:2047–8. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sokolove J, Brennan MJ, Sharpe O, et al. . Brief report: citrullination within the atherosclerotic plaque: a potential target for the anti-citrullinated protein antibody response in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:1719–24. 10.1002/art.37961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lundkvist A, Reichenbach A, Betsholtz C, et al. . Under stress, the absence of intermediate filaments from Muller cells in the retina has structural and functional consequences. J Cell Sci 2004;117 (Pt 16):3481–8. 10.1242/jcs.01221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Martinez G, Gómez JA, Bang H, et al. . Carbamylated vimentin represents a relevant autoantigen in Latin American (Cuban) rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatol Int 2016;36:781–91. . 10.1007/s00296-016-3472-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sirpal S. Myeloperoxidase-mediated lipoprotein carbamylation as a mechanistic pathway for atherosclerotic vascular disease. Clin Sci 2009;116:681–95. 10.1042/CS20080322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Harre U, Georgess D, Bang H, et al. . Induction of osteoclastogenesis and bone loss by human autoantibodies against citrullinated vimentin. J Clin Invest 2012;122:1791–802. 10.1172/JCI60975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ospelt C, Camici GG, Engler A, et al. . Smoking induces transcription of the heat shock protein system in the joints. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1423–6. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Juarez M, Bang H, Hammar F, et al. . Identification of novel antiacetylated vimentin antibodies in patients with early inflammatory arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:1099–107. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Detert J, Bastian H, Listing J, et al. . Induction therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate for 24 weeks followed by methotrexate monotherapy up to week 48 versus methotrexate therapy alone for DMARD-naive patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: HIT HARD, an investigator-initiated study. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:844–50. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Källberg H, Ding B, Padyukov L, et al. . Smoking is a major preventable risk factor for rheumatoid arthritis: estimations of risks after various exposures to cigarette smoke. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:508–11. 10.1136/ard.2009.120899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lugli EB, Correia RE, Fischer R, et al. . Expression of citrulline and homocitrulline residues in the lungs of non-smokers and smokers: implications for autoimmunity in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2015;17:9 10.1186/s13075-015-0520-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brink M, Verheul MK, Ronnelid J, et al. . Anti-carbamylated protein antibodies in the pre-symptomatic phase of rheumatoid arthritis, their relationship with multiple anti-citrulline peptide antibodies and association with radiological damage. Arthritis Res Ther 2015;17:25 10.1186/s13075-015-0536-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shi J, van Steenbergen HW, van Nies JA, et al. . The specificity of anti-carbamylated protein antibodies for rheumatoid arthritis in a setting of early arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2015;17:339 10.1186/s13075-015-0860-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bang SY, Lee KH, Cho SK, et al. . Smoking increases rheumatoid arthritis susceptibility in individuals carrying the HLA-DRB1 shared epitope, regardless of rheumatoid factor or anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody status. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:369–77. 10.1002/art.27272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Snir O, Gomez-Cabrero D, Montes A, et al. . Non-HLA genes PTPN22, CDK6 and PADI4 are associated with specific autoantibodies in HLA-defined subgroups of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2014;16:414 10.1186/s13075-014-0414-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Challener GJ, Jones JD, Pelzek AJ, et al. . Anti-carbamylated Protein Antibody Levels Correlate with Anti-Sa (Citrullinated Vimentin) Antibody Levels in Rheumatoid Arthritis. J Rheumatol 2016;43:273–81. 10.3899/jrheum.150179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

annrheumdis-2016-210059supp001.pdf (281.3KB, pdf)