Abstract

Objectives

To assess baricitinib on patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in patients with moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis, who had insufficient response or intolerance to ≥1 tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFis) or other biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs).

Methods

In this double-blind phase III study, patients were randomised to once-daily placebo or baricitinib 2 or 4 mg for 24 weeks. PROs included the Short Form-36, EuroQol 5-D, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F), Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index (HAQ-DI), Patient's Global Assessment of Disease Activity (PtGA), patient's assessment of pain, duration of morning joint stiffness (MJS) and Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire-Rheumatoid Arthritis. Treatment comparisons were performed with logistic regression for categorical measures or analysis of covariance for continuous variables.

Results

527 patients were randomised (placebo, 176; baricitinib 2 mg, 174; baricitinib 4 mg, 177). Both baricitinib-treated groups showed statistically significant improvements versus placebo in most PROs. Improvements were generally more rapid and of greater magnitude for patients receiving baricitinib 4 mg than 2 mg and were maintained to week 24. At week 24, more baricitinib-treated patients versus placebo-treated patients reported normal physical functioning (HAQ-DI <0.5; p≤0.001), reductions in fatigue (FACIT-F ≥3.56; p≤0.05), improvements in PtGA (p≤0.001) and pain (p≤0.001) and reductions in duration of MJS (p<0.01).

Conclusions

Baricitinib improved most PROs through 24 weeks compared with placebo in this study of treatment-refractory patients with previously inadequate responses to bDMARDs, including at least one TNFi. PRO results aligned with clinical efficacy data for baricitinib.

Trial registration number

NCT01721044; Results.

Keywords: DMARDs (synthetic), DMARDs (biologic), Patient perspective, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Outcomes research

Introduction

The inflammatory activity and joint damage associated with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) often result in impairment in physical function, and other impairments important to patients; effective therapy can dramatically improve these outcomes.1–3 Importantly, impairment in physical function is a consequence of both disease activity and irreversible, progressive joint damage.4–6 Patients with long-standing disease who have undergone treatment with several conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (csDMARD) therapies and also failed to respond sufficiently to biological DMARDs (bDMARDs) constitute a group with severe and particularly treatment-refractory disease.7 These patients may therefore be at increased risk for a lack of significant improvement in physical function or other patient-reported outcomes (PROs) on introduction of new therapies.7–9 Subsequently, despite the availability of several bDMARDs, there is an unmet need for more treatment options for such patients.

Patient input is important for shared decision-making, an overarching principle in most recommendations for the management of RA,10 as improvements in symptoms and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) are usually more relevant to patients than clinical or serological changes alone. Indeed, the burden of RA as reported by patients is considered an important aspect of RA management.11 12 As evaluation of PROs reflects part of the overall effectiveness assessment of csDMARDs and bDMARDs, such measures are included in RA clinical trials.13 14 Many PRO measures are available for this purpose and assess the range of potentially affected health domains such as pain, disease activity, physical functioning, fatigue, sleep disturbance, psychological disorders, well-being at work and QOL.

Baricitinib is a highly selective inhibitor of Janus kinase (JAK)1/JAK2 that interferes with pathways believed to be important in the pathogenesis of RA.15 In the RA-BEACON study, baricitinib was efficacious in patients who had failed previous treatment with several csDMARDs and one or more tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFis) as well as non-TNFi bDMARDs.16 This manuscript describes the PRO data collection in RA-BEACON and assesses whether the efficacy of baricitinib demonstrated in RA-BEACON is reflected by clinically meaningful changes in PROs.

Methods

Patients and study design

RA-BEACON (NCT01721044) was a randomised, 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre, international phase III study. Full details of the study have been reported previously.16 Briefly, patients were randomly assigned (1:1:1) to receive once-daily placebo or baricitinib 2 or 4 mg in addition to the therapies they were already receiving at enrolment. Patients whose tender and swollen joint counts at baseline were reduced by <20% at both week 14 and week 16 received rescue treatment, baricitinib 4 mg daily. Patients were ≥18 years of age and had moderately to severely active RA, defined as a tender joint count of ≥6 and a swollen joint count ≥6 (68/66 joint count) and C-reactive protein ≥3 mg/L. Patients were required to have received one or more TNFis and discontinued treatment due to insufficient response after ≥3 months or to intolerance and could have received other bDMARDs. Biological DMARDs must have been discontinued for ≥4 weeks before randomisation (≥6 months for rituximab). Patients must have been regularly using ≥1 csDMARDs for ≥12 weeks prior to study entry at a stable dose for ≥8 weeks. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines and approved by the institutional review board or ethics committee for each centre involved. All patients provided written informed consent.

Patient-reported outcomes

Several PROs were prespecified secondary outcomes of the study.

The Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Short Form-36 (SF-36; V.2, Acute)17 18 was used to assess HRQOL in eight domains scored from 0 to 100 that are normalised into physical (PCS) and mental (MCS) component scores. A minimum clinically important difference (MCID) of 5 was used to assess the clinical relevance of changes in SF-36 scores (both domains and component scores),19 20 and a sensitivity analysis with an MCID of 2.5 was also evaluated. The EuroQol 5-Dimensions (EQ-5D 5L) Health State Profile was also used to assess HRQOL. The EQ-5D 5L consists of two components: a descriptive system of the respondent's health and a rating of his/her current health state (visual analogue scale, VAS; 0–100 mm), in which the endpoints are labelled ‘best imaginable health state (100)’ and ‘worst imaginable health state (0)’.21 The UK and US scoring algorithms provide an index score using the UK or US population weighting to normalise it to that population;22–24 index scores range from 0 (death) to 1 (perfect health).

Fatigue was assessed using the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F) scale (range 0–52), with higher scores representing less fatigue.25 For the FACIT-F, a three to four-point change has been considered an MCID,25 26 and in this study a value of 3.5627 was used to assess the clinical relevance of changes in FACIT-F scores. Duration of morning joint stiffness (MJS) was reported by the patient as the length of time (minutes) that MJS lasted on the day prior to the study visit.

Physical function was measured using the Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index (HAQ-DI).28 29 Scores range from 0–3, with lower scores reflecting better physical function and thus, less disability. HAQ-DI score changes were assessed in the context of an MCID of 0.22.30 Disease activity and pain were measured using the Patient's Global Assessment of Disease Activity (PtGA) and the patient's assessment of pain VAS (0–100 mm), in which higher scores indicate more disease activity or pain.

The Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire-Rheumatoid Arthritis (WPAI-RA) scale was used to measure the health and symptoms of overall work productivity and impairment of regular activities during the past 7 days. Scores are calculated as impairment percentages,31 with higher percentages indicating greater impairment and less productivity.

Most PROs were assessed at baseline and at weeks 1, 2, 4 and every 4 weeks thereafter to week 24, with the exceptions of the WPAI-RA (not collected at week 1) and the SF-36, EQ-5D and FACIT-F data (collected at baseline, week 4 and then every 4 weeks until week 24).

Statistical analyses

Patients who were randomised and treated with ≥1 doses of placebo, baricitinib 2 or 4 mg were included in this analysis.

Comparisons of treatment groups (ie, baricitinib 2 mg vs placebo or baricitinib 4 mg vs placebo) for categorical measures were performed using logistic regression with geographical region and number of previous bDMARDs (<3, ≥3) as explanatory factors. When sample size requirements for logistic regression were not met (<5 responders in any category for any factor), the Fisher exact test was used. Comparisons of continuous measures were performed using analysis of covariance, with baseline score, geographical region and number of previous bDMARDs (<3, ≥3) as explanatory factors. For the duration of MJS, the p value for the median difference of change from baseline was calculated using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Any duration of MJS lasting >12 hours was truncated to 720 min for the purpose of this analysis.

Patients who were rescued or discontinued from the study or study treatment were thereafter defined as non-responders (non-responder imputation) for analysis of categorical data. These patients also had their last observations before rescue or discontinuation used for analyses of continuous data (modified last observation carried forward). However, the WPAI-RA measures were censored after rescue or discontinuation without imputation applied.

All analyses are based on a significance level of 0.05 (two-sided). p Values were not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Results

Patients

A total of 527 patients were randomised: 176 received placebo, 174 received baricitinib 2 mg and 177 received baricitinib 4 mg. Patient disposition has been described by Genovese et al.16 Baseline patient characteristics and disease activity were similar between the groups (see online supplementary table S1).16 Overall, almost 60% of the patients had previously received >1 bDMARD; 221 (42%), 160 (30%) and 142 (27%) patients, respectively, had previously received 1, 2 or ≥3 bDMARDs. Indeed, more than one-third of the patients enrolled in the study had an inadequate response to, or side effects associated with, both TNFi and non-TNFi bDMARDs.16 Baseline PRO values were similar across the treatment groups and indicated a significant disease burden, consistent with the combined effect of baseline clinical disease activity and disease duration16 (see online supplementary table S1).

annrheumdis-2016-209821supp001.pdf (428.6KB, pdf)

Patient-reported outcomes

Over 24 weeks, most PROs improved significantly among patients receiving baricitinib compared with placebo, with patients in the baricitinib 4 mg group showing a more rapid and greater magnitude of change than the baricitinib 2 mg group.

Health-related quality of life

The eight SF-36 domain scores at week 12 and week 24 were assessed. Patients treated with baricitinib 2 or 4 mg reported statistically significantly improved differences from baseline compared with placebo in most of the domains at both time points, except for the mental health domain which improved but did not achieve statistical significance (see online supplementary table S2). Compared with placebo, a statistically significantly larger proportion of patients treated with baricitinib met or exceeded the MCID in four domains (physical functioning, bodily pain, vitality and social functioning) for baricitinib 4 mg and in four domains for baricitinib 2 mg (physical functioning, bodily pain, general health and vitality) at week 12 (figure 1A); at week 24, significant differences were observed in three domains for baricitinib 4 mg (physical functioning, vitality and social functioning) and in two domains for the baricitinib 2 mg group (physical functioning and social functioning) (figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Percentage of patients reporting scores that met or exceeded the MCID. (A) SF-36 domains at week 12. (B) SF-36 domains at week 24. MCID, minimum clinically important difference; SF-36, Short Form-36.

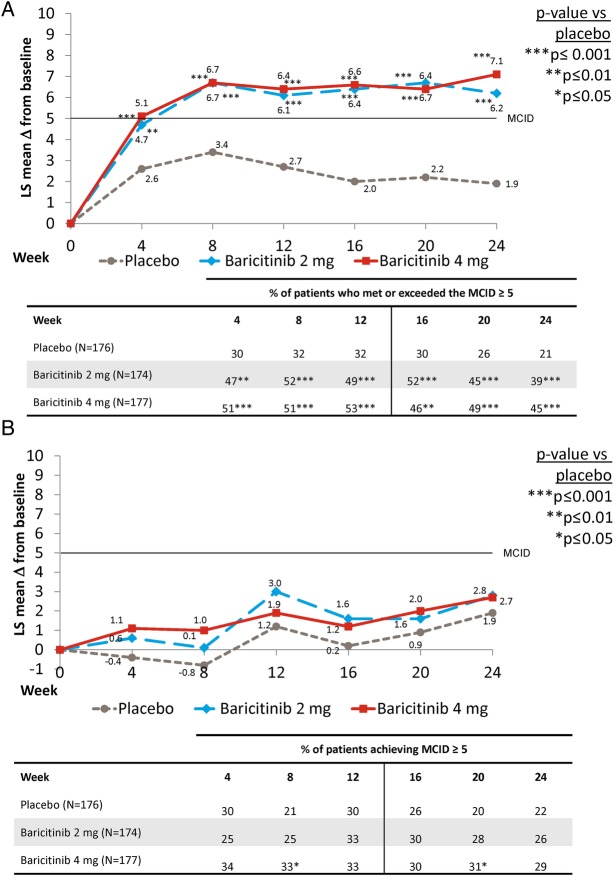

For the SF-36 PCS, the least-squares mean (LSM) change from baseline for both baricitinib-treated groups were statistically greater compared with placebo and had improved from the first postbaseline assessment at week 4 and maintained this response at week 24 (figure 2A). At both weeks 12 and 24, the proportion of patients who met or exceeded the MCID in both baricitinib-treated groups was statistically significantly larger than placebo (p=0.001 for both baricitinib groups vs placebo at both time points) (figure 2A). However, for the SF-36 MCS measure, no significant differences in the LSM change from baseline were found between the baricitinib-treated groups and placebo, although numerical differences were observed. The proportion of patients who met or exceeded the MCID ≥5 for the MCS was statistically significantly different from the placebo group only for the patients in the baricitinib 4 mg group at weeks 8 and 20 (figure 2B). Results were similar for the MCID value of 2.5 (see online supplementary table S3).

Figure 2.

Change from baseline for the (A) Physical Component Score and (B) Mental Component Score for the SF-36 and percentage of patients reporting scores that met or exceeded the MCID. LS, least squares; MCID, minimum clinically important difference; SF-36, Short Form-36.

A statistically significant difference in change in the EQ-5D UK index score was observed at the first postbaseline assessment (at week 4) for baricitinib 4 mg, but not baricitinib 2 mg, compared with placebo (data not shown). By weeks 12 and 24, however, statistically significant improvements in the EQ-5D UK index score were observed for both baricitinib-treated groups versus placebo (table 1). For the EQ-5D VAS at 4 weeks, baricitinib-treated patients reported statistically significantly higher scores than placebo-treated patients (data not shown). These results were maintained to weeks 12 and 24 (table 1). Results were similar with the US algorithm for the EQ-5D index score (table 1).

Table 1.

Patient-reported outcomes at week 12 and week 24

| Patient-reported outcome measure (least-squares mean (95% CI) from baseline at week 12 or 24, unless specified otherwise) | Week 12 |

Week 24 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (N=176) |

Baricitinib 2 mg (N=174) |

Baricitinib 4 mg (N=177) |

Placebo (N=176) |

Baricitinib 2 mg (N=174) |

Baricitinib 4 mg (N=177) |

|

| EQ-5D-5L | ||||||

| Health State Index Score | ||||||

| UK algorithm | 0.036 (−0.000 to 0.073) | 0.114*** (0.077 to 0.150) | 0.169*** (0.133 to 0.205) | 0.038 (−0.000 to 0.076) | 0.111** (0.073 to 0.149) | 0.159*** (0.122 to 0.197) |

| US algorithm | 0.026 (0.001 to 0.051) | 0.079*** (0.054 to 0.103) | 0.116*** (0.091 to 0.141) | 0.025 (−0.002 to 0.051) | 0.074** (0.048 to 0.100) | 0.107*** (0.081 to 0.133) |

| VAS | 2.9 (−1.1 to 6.9) | 11.3*** (7.3 to 15.4) | 9.0* (5.0 to 12.9) | 1.9 (−2.3 to 6.2) | 7.9* (3.7 to 12.2) | 11.3*** (7.1 to 15.5) |

| Physical function (HAQ-DI) | −0.17 (−0.26 to −0.08) | −0.37*** (−0.46 to −0.28) | −0.41*** (−0.49 to −0.32) | −0.15 (−0.24 to −0.05) | −0.38*** (−0.47 to −0.29) | −0.43*** (−0.52 to −0.34) |

| % with HAQ-DI <0.5 | 6% | 14%* | 14%* | 3% | 16%*** | 16%*** |

| PtGA (VAS) | −8.9 (−13.0 to −4.9) | −20.4*** (−24.4 to −16.3) | −23.0*** (−27.0 to −19.0) | −8.8 (−13.1 to −4.6) | −20.3*** (−24.6 to −16.1) | −24.8*** (−29.0 to −20.6) |

| Patient's assessment of pain (VAS) | −8.8 (−12.9 to −4.7) | −17.1*** (−21.2 to −13.0) | −22.3*** (−26.3 to −18.2) | −8.8 (−13.2 to −4.3) | −18.8*** (−23.2 to −14.4) | −24.0*** (−28.5 to −19.6) |

| FACIT-F | 5.2 (3.5 to 6.9) | 8.3** (6.6 to 9.9) | 8.1** (6.5 to 9.8) | 5.7 (4.0 to 7.5) | 8.1* (6.4 to 9.9) | 9.2** (7.5 to 11.0) |

Lower scores indicate better outcomes for HAQ-DI, PtGA, patient's assessment of pain. Higher scores indicate better outcomes for EQ-5D.

*p≤0.05, **p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001 versus placebo.

EQ-5D-5L, European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions-5 Levels; FACIT-F, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index; PtGA, Patient's Global Assessment of Disease Activity; VAS, visual analogue scale.

FACIT-F and duration of MJS

Treatment with baricitinib 2 and 4 mg was associated with significant improvements in the FACIT-F at week 4 compared with placebo, the first assessment of this measure (figure 3A). For duration of MJS, baricitinib 4 mg, but not 2 mg, was statistically significantly improved from placebo at week 1 (figure 3B). Improvements in the FACIT-F score and reductions in the duration of MJS were sustained to week 12 and week 24 (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Change in baseline over time for the (A) FACIT-F and (B) duration of morning joint stiffness. FACIT-F, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue; LS, least squares; MCID, minimum clinically important difference.

For the FACIT-F, there were more patients in the baricitinib-treated groups who met or exceeded the MCID at week 12 (p=0.004 for baricitinib 2 mg vs placebo and p=0.007 for baricitinib 4 mg vs placebo) as well as at week 24 (p=0.015 for baricitinib 2 mg vs placebo and p=0.005 for baricitinib 4 mg vs placebo) (figure 3A).

HAQ-DI, PtGA and pain

The percentage of patients with HAQ-DI scores <0.5 (the normal function cutpoint for patients with established RA),32 for placebo, baricitinib 2 mg and baricitinib 4 mg was 6%, 14% and 14%, respectively (p≤0.05 for baricitinib 2 mg and 4 mg vs placebo), at week 12 and was 3%, 16% and 16%, respectively, at week 24 (p≤0.001 for baricitinib 2 and 4 mg vs placebo) (table 1).

As previously reported,16 for HAQ-DI and PtGA, differences in improvements in the baricitinib-treated groups versus placebo were evident as early as week 1, the first postrandomisation assessment time point; for patient's assessment of pain, only baricitinib 4 mg was statistically significantly different from placebo at week 1. Significant improvements in HAQ-DI and reductions in PtGA and pain (VAS) were maintained at week 12 and week 24, the end of the study (table 1).

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses according to the type (TNFi vs non-TNFi) or number (<3 vs ≥3) of previous bDMARDs used revealed no consistent, significant differences in outcomes of FACIT-F, duration of MJS, HAQ-DI or patient's assessment of pain (VAS) at weeks 12 and 24.

Work productivity and activity impairment

At baseline, only 30%–40% of the patients reported employment. Of this number, 90%–94% continued to report employment at week 12 and 82%–89% continued to report employment at week 24 (see online supplementary table S4).

Patients treated with baricitinib 2 and 4 mg reported a statistically significant reduction in daily activity impairment compared with placebo at weeks 12 and 24 (see online supplementary table S4). Among those patients who were employed at baseline and those who maintained employment at weeks 12 and 24, there were reduced presenteeism (percentage of work-time impaired) and work productivity loss in baricitinib-treated groups but these did not reach statistical significance compared with placebo; similar results were observed for absenteeism at week 12, but were not maintained at week 24 (see online supplementary table S4).

Discussion

This analysis of RA-BEACON16 evaluated whether the clinical efficacy data for baricitinib (with background csDMARDs) were complemented by respective changes in PROs in patients with a previous inadequate response to one or more bDMARDs, including at least one TNFi, regardless of the number and type of previous csDMARDs and bDMARDs. This question was particularly important given the refractory nature and long disease duration of the patient population studied as the responsiveness of PROs decreases dramatically with increasing failure of prior therapies and disease duration.7 The disease duration of about 14 years in this trial is one of the longest of any recently published RA clinical trial. Disease durations such as these have been associated with a failure to improve physical function significantly on biological agents compared with placebo.7

Prespecified secondary outcomes in the RA-BEACON trial included a number of PROs that reflect disease activity (duration of MJS and fatigue by FACIT-F), physical function (HAQ-DI, SF-36 PCS), work productivity (WPAI-RA) and HRQOL (SF-36, EQ-5D), some of which constitute patient ratings of the American College of Rheumatology core set measures (HAQ-DI, PtGA and patient's assessment of pain).33 The use of all these measures allowed a thorough evaluation of the effects of baricitinib on the various aspects of patient well-being.

Baseline PROs revealed severely impaired physical function and high levels of pain and fatigue. Patients receiving baricitinib had significantly higher degrees of improvements in most PROs over 24 weeks compared with placebo. Improvements were generally more rapid and of greater magnitude with baricitinib 4 mg than baricitinib 2 mg. In addition, the PRO improvements between the treatment groups and placebo were not influenced by the type (TNFi or non-TNFi) or number (<3 or ≥3) of previous bDMARDs used. The proportion of patients with improvements in the HAQ-DI and SF-36 PCS was significant in both baricitinib groups compared with placebo, and, indeed, significantly more patients reported achieving normal physical functioning (HAQ-DI <0.5). Patients receiving baricitinib also reported a significant improvement in EQ-5D scores, pain, MJS duration and fatigue as well as in regular activity (WPAI-RA) compared with the placebo group. By contrast, for the SF-36 MCS measure, no significant differences were observed between patients treated with baricitinib compared with placebo, consistent with previous observations from other clinical trials.26 27 34 35 The baseline value of the MCS was approximately 46 across the treatment groups, demonstrating only a modest impairment, in contrast to the significant physical impairment seen with the PCS (approximately 29 at baseline). Patients, therefore, did not have as much opportunity to improve their MCS scores.

Improvements in PROs associated with baricitinib in the present analysis were in the range of those reported with bDMARDs in patients with just an inadequate response to csDMARDs or to TNFis.26 27 34 35–37 Over 6 months, the difference in the rates of patients showing improvement that was ≥MCID in the HAQ-DI and the SF-36 PCS, amounted to 23% between baricitinib 4 mg and placebo. This difference was similar to that reported with a bDMARD (improvement of ∼40%–65%) versus placebo (improvement of ∼25%–35%).27 34–36 38 However, in the current trial, patients had failed to respond to ≥1 bDMARDs, with approximately 60% having previously received two bDMARDs or more. Therefore, these patients with long-standing disease can be considered a refractory population, which is increasing over time and has a substantial unmet need in RA.

To our knowledge, no other randomised controlled trial has evaluated PROs and drug effects in such a refractory population. In a randomised controlled trial of tofacitinib in patients with inadequate response to TNFis (but overall much lower proportions of patients with multiple bDMARD failure), the PROs reported included pain, PtGA, HAQ-DI, FACIT-F, SF-36 and MOS Sleep Scale.26 39 Treatment effects from that study26 39 are consistent with our data showing meaningful outcomes for patients treated with JAK inhibitors.

This study has some limitations. The 24-week follow-up period is insufficient to determine the longer-term effects of baricitinib treatment. Long-term observations are required to assess the durability of the observed changes; such a study is currently ongoing. However, other extension studies have not shown major losses of response over time.40 41 Further, a high placebo response, most notably for the FACIT-F score, was observed. This could be related to patients being seen more often than in clinical practice and/or showing better adherence to their medication, but these factors are also potentially true for most other randomised controlled trials. However, the proportion of patients who reported improvements that met or exceeded the MCID for the FACIT-F score was 62.7% and 63.8% for baricitinib 4 and 2 mg, respectively, versus 48.3% in the placebo group. The difference in fatigue improvement between baricitinib and placebo treatment from week 4 onwards was encouraging, since it was not related to increases in haemoglobin,16 but rather to the improvement in inflammatory response, pain and disability. The fact that the employment status did not improve significantly is not surprising and likely related to the short duration of the trial; patients with long-standing, disease-associated unemployment are unlikely to search for and find a new job within a period of 6 months. Additionally, patients from 21 countries participated in the trial, and different rates of unemployment and policies related to workplace accommodations may influence a patient's employment status.

The strengths of this study include the assessment of a number of well-established PRO measures and a patient population with important unmet needs, many of whom had tried several bDMARDs and would not have been very likely to achieve disease control with currently available therapies. Importantly, both physical function and HRQOL measures improved to a relatively large extent across several assessment methods. The major reduction in duration of MJS reflects the patients' overall improvement in clinical disease activity beyond that assessed by global assessments of pain and activity.

In conclusion, in this treatment-refractory population of patients with previously inadequate responses to bDMARDs, including at least one TNFi, baseline PROs revealed severely impaired physical function and a high level of pain and fatigue. Significant improvements in PROs occurred rapidly with baricitinib and were sustained throughout 24 weeks. Improvements were generally more rapid and of greater magnitude for patients receiving baricitinib 4 mg compared with baricitinib 2 mg. These data are in agreement with previously reported clinical efficacy data for baricitinib in patients with RA, suggesting that baricitinib may be an effective treatment for patients with inadequate response to bDMARDs.

Acknowledgments

This study and manuscript were sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company and Incyte Corporation. The authors would like to acknowledge Claire Lavin and Clare Gurton (Rx Communications) for medical writing assistance with the preparation of this manuscript and Barbara Coffey and Molly Tomlin (Eli Lilly) for their assistance with process support. The authors would also like to thank all patients and study investigators.

Footnotes

Contributors: JSS, BC and CG have worked on the major parts of the manuscript and the revisions. All other authors have significantly contributed to the interpretation of the data, participated in the development of later stages of the manuscript and critically reviewed the final version.

Competing interests: JSS has received grants for his institution from Abbvie, Janssen, Eli Lilly and Company, MSD, Pfizer, Roche and has provided expert advice to and/or had speaking engagements for Abbvie, Amgen, Astra-Zeneca, Astro, Celgene, Celtrion, GSK, ILTOO, Janssen, Eli Lilly and Company, Medimmune, MSD, Novartis-Sandoz, Novo-Nordisk, Pfizer, Roche, Samsung, Sanofi, UCB. JMK has received research grant support and consultation honoraria from Eli Lilly and Company. He is an officer and stockholder in Corrona. He has received research grant support from Abbvie, Novartis, Amgen and Pfizer. He is on the speaker's bureau for Genentech. CLG, AMD, DES, LX, IS and TR are full-time employees of Eli Lilly and Company and DES, LX, IS and TR are minor shareholders of Eli Lilly and Company. PB has received grants and consulting fees from Abbvie, Pfizer, Novartis, Eli Lilly and Company, Roche, BMS and Jannsen. JMSB has received grants and consulting fees from Abbvie, Pfizer, UCB and Gebro. MCG has received grants and consulting fees from Abbvie, Astellas, Eli Lilly and Company, Galapagos, Gilead, Pfizer and Vertex. BC has received honorarium from Abbvie, BMS, Eli Lilly and Company, MSD, Pfizer, Roche-Chugai and UCB.

Ethics approval: All local ethical committees.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Carr A, Hewlett S, Hughes R, et al. Rheumatology outcomes: the patient's perspective. J Rheumatol 2003;30:880–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strand V, Cohen S, Crawford B, et al. Patient-reported outcomes better discriminate active treatment from placebo in randomized controlled trials in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43:640–7. 10.1093/rheumatology/keh140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klarenbeek NB, Güler-Yüksel M, van der Kooij SM, et al. The impact of four dynamic, goal-steered treatment strategies on the 5-year outcomes of rheumatoid arthritis patients in the BeSt study. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:1039–46. 10.1136/ard.2010.141234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drossaers-Bakker KW, de Buck M, van Zeben D, et al. Long-term course and outcome of functional capacity in rheumatoid arthritis: the effect of disease activity and radiologic damage over time. Arthritis Rheum 1999;42:1854–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aletaha D, Smolen J, Ward MM. Measuring function in rheumatoid arthritis: Identifying reversible and irreversible components. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2784–92. 10.1002/art.22052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Grisar JC, et al. Estimation of a numerical value for joint damage-related physical disability in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1058–64. 10.1136/ard.2009.114652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aletaha D, Strand V, Smolen JS, et al. Treatment-related improvement in physical function varies with duration of rheumatoid arthritis: a pooled analysis of clinical trial results. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:238–43. 10.1136/ard.2007.071415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aletaha D, Ward MM. Duration of rheumatoid arthritis influences the degree of functional improvement in clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:227–33. 10.1136/ard.2005.038513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smolen JS, Aletaha D. Rheumatoid arthritis therapy reappraisal: strategies, opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2015;11:276–89. 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smolen JS, Landewé R, Breedveld FC, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2013 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:492–509. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL Jr, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:1–26. 10.1002/art.39480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanderson T, Morris M, Calnan M, et al. What outcomes from pharmacologic treatments are important to people with rheumatoid arthritis? Creating the basis of a patient core set. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62:640–6. 10.1002/acr.20034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gossec L, Dougados M, Dixon W. Patient-reported outcomes as end points in clinical trials in rheumatoid arthritis. RMD Open 2015;1:e000019 10.1136/rmdopen-2014-000019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aletaha D, Landewe R, Karonitsch T, et al. Reporting disease activity in clinical trials of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: EULAR/ACR collaborative recommendations. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:1371–7. 10.1002/art.24123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Shea JJ, Holland SM, Staudt LM. JAKs and STATs in immunity, immunodeficiency, and cancer. N Engl J Med 2013;368:161–70. 10.1056/NEJMra1202117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Genovese MC, Kremer J, Zamani O, et al. Baricitinib in patients with refractory rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1243–52. 10.1056/NEJMoa1507247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NM, et al. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ 1992;305:160–4. 10.1136/bmj.305.6846.160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical care 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strand V, Singh JA. Newer biological agents in rheumatoid arthritis: impact on health-related quality of life and productivity. Drugs 2010;70:121–45. 10.2165/11531980-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kosinski M, Zhao SZ, Dedhiya S, et al. Determining minimally important changes in generic and disease-specific health-related quality of life questionnaires in clinical trials of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:1478–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.EuroQol Group. EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199–208. 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy 1996;37:53–72. 10.1016/0168-8510(96)00822-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.EuroQol Group. EQ-5D-5L User Guide. Version 1.0. April 2011. Originally accessed at: http://www.euroqol.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Documenten/PDF/Folders_Flyers/UserGuide_EQ-5D-5L.pdf (accessed 1 Jul 2012).

- 24.Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 2011;20: 1727–36. 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cella D, Yount S, Sorensen M, et al. Validation of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy Fatigue Scale relative to other instrumentation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2005;32:811–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strand V, Burmester GR, Zerbini CA, et al. Tofacitinib with methotrexate in third-line treatment of patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: patient-reported outcomes from a phase III trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2015;67:475–83. 10.1002/acr.22453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keystone E, Burmester GR, Furie R, et al. Improvement in patient-reported outcomes in a rituximab trial in patients with severe rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:785–93. 10.1002/art.23715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruce B, Fries JF. The Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ). Clin Exp Rheumatol 2005;23(Suppl 39):S14–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramey DR, Fries JF, Singh G. The Health Assessment Questionnaire 1995: status and review. In: Spiker B. Quality of life and pharmacoeconomics in clinical trials. 2nd edn Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1996:227–37. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wells GA, Tugwell P, Kraag GR, et al. Minimum important difference between patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the patient's perspective. J Rheumatol 1993;20:557–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics 1993;4:353–65. 10.2165/00019053-199304050-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Navarro-Compán V, Smolen JS, Huizinga TWJ, et al. Quality indicators in rheumatoid arthritis: results from the METEOR database. Rheumatology 2015;54:1630–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/kev108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary core set of disease activity measures for rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. The Committee on Outcome Measures in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trials. Arthritis Rheum 1993;36:729–40. 10.1002/art.1780360601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strand V, Burmester GR, Ogale S, et al. Improvements in health-related quality of life after treatment with tocilizumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis refractory to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors: results from the 24-week randomized controlled RADIATE study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51:1860–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/kes131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Westhovens R, Cole JC, Li T, et al. Improved health-related quality of life for rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with abatacept who have inadequate response to anti-TNF therapy in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre randomized clinical trial. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45:1238–46. 10.1093/rheumatology/kel066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smolen JS, Kay J, Doyle MK, et al. Golimumab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis after treatment with tumour necrosis factor alpha inhibitors (GO-AFTER study): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial. Lancet 2009;374:210–21. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60506-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strand V, Smolen JS, van Vollenhoven RF, et al. Certolizumab pegol plus methotrexate provides broad relief from the burden of rheumatoid arthritis: analysis of patient-reported outcomes from the RAPID 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:996–1002. 10.1136/ard.2010.143586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keystone EC, Genovese MC, Klareskog L, et al. Golimumab, a human antibody to tumour necrosis factor {alpha} given by monthly subcutaneous injections, in active rheumatoid arthritis despite methotrexate therapy: the GO-FORWARD Study. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:789–96. 10.1136/ard.2008.099010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burmester GR, Blanco R, Charles-Schoeman C, et al. Tofacitinib (CP-690,550) in combination with methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors: a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013;381:451–60. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61424-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keystone EC, van der Heijde D, Kavanaugh A, et al. Clinical, functional, and radiographic benefits of longterm adalimumab plus methotrexate: final 10-year data in longstanding rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2013;40:1487–97. 10.3899/jrheum.120964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Genovese MC, Schiff M, Luggen M, et al. Longterm safety, efficacy of abatacept through 5 years of treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy. J Rheumatol 2012;39:1546–54. 10.3899/jrheum.111531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

annrheumdis-2016-209821supp001.pdf (428.6KB, pdf)