Abstract

Objectives

To assess rates of tube insertions for otitis media with effusion (OME) with estimates of need.

Study Design

This cross-sectional analysis used all-payer claims to calculate rates of tube insertions for insured children age 2 to 8 years (2007–2010) across pediatric surgical areas (PSA) for Northern New England (NNE; Maine, Vermont, and New Hampshire) and the English National Health Service Primary Care Trusts (PCT). These rates were compared to expected rates estimated using a Monte Carlo simulation model that integrates clinical guidelines and published probabilities of the incidence and course of OME.

Results

Observed rates of tympanostomy tubes varied >30-fold across English PCTs (N=150) and >3-fold across NNE PSAs (N=30). At a 25 dB hearing threshold the overall difference in observed to expected tympanostomy tubes provided was −3.41 per 1,000 children in England and −0.01 per 1,000 children in NNE. Observed incidence of insertion was less than expected in all but eight PCTs while higher than expected in half of the PSAs. Using a 20 dB hearing threshold, there were fewer tube insertions than expected in all but 2 England and 7 NNE areas. There was an inverse relationship between estimated need and observed tube insertion rates.

Conclusions

Regional variations in observed tympanostomy tube insertion rates are unlikely to be due to differences in need and suggest overall underuse in England and both over and underuse in NNE.

Keywords: Overuse and underuse, Unwarranted variation, Geography, Tympanostomy tube, Otitis media with effusion, Clinical guidelines, Appropriateness, Child

Introduction

Otitis media is the most common childhood diagnosis with 2.2 million children affected before school age and with the highest prevalence occurring between 6 months to 3 years old1. In 90% of children, a middle ear effusion develops subsequently and in 40% it persists for more than 3 months1,2. Insertion of tympanostomy tubes (grommets) to relieve otitis media with effusion (OME) or reduce recurrent otitis media is the most common pediatric procedure in the United States, accounting for more than 20% of all pediatric ambulatory surgery, with annual associated costs exceeding $5 billion.3

Rates of tympanostomy tube insertion are known to vary across regions in the U.S., England, Canada, Finland, and Norway.4–11 Although Black found that there was a reduction in the mean rate for England following clinical guidelines issued in the 1990s, which were already half the rate of the US, substantial variation in rates of treatment continued.2,10,12–15 This variation could be due to differences in need and preferences of patients, and for this procedure, the preferences of their parents. However, using RAND – UCLA appropriateness criteria7,8 and patient data from chart reviews, a significant majority of U.S. tympanostomy insertions were found to be inappropriate. For example, a key finding from a study of tympanostomy insertions in England16 was the suggestion that there appeared to be both over- and under-treatment: i.e. operations were carried out on patients who were unlikely to benefit and not on patients for whom the benefit was likely.

In this paper we move from descriptions of variations in rates of treatment to normative assessments, by developing estimates of “need” in terms of likely capacity to benefit in England and Northern New England (NNE). We did this by using a model based on England’s National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines,17 that are similar to those developed by the American Academy of Pediatrics.1 This provides evidence of the likely extent of over and underuse of tympanostomy tubes, in two countries with very different funding and organization of health care.

Methods

Data and Population

This study measured the use of tympanostomy tubes in children age 2 to 8 years residing in Maine, Vermont, and New Hampshire and registered with the English NHS during the period 2007–2010. For NNE we used pediatric all-payer administrative datasets limited to children with one or more months enrollment in a Medicaid or commercial insurance plan that met state-level data-reporting mandates.18 For England, private paying patients were not included.

We included both in and outpatient cases and included tube insertions listed as both primary and secondary procedures. For NNE, tympanostomy tube placements were identified by claims with Current Procedural Terminology codes 69433 and 69436 in addition to International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnosis codes of otitis media with effusion of chronic middle ear disease (381.1, 381.19, 381.20, 381.29, 381.3, and 381.4). It should be noted that claims do not distinguish bilateral from unilateral disease. For England, observed rates were calculated by using a four-year average (2007/2008 – 2010/2011). Tympanostomy tube insertion was identified using NHS procedure codes with ICD-10 diagnosis codes (H652, H653, H654, and H659) and indicates that a child had one or two tubes placed.

For NNE, rates are reported across Dartmouth Atlas Pediatric Surgical Areas (PSA; N=30) that were developed for The Dartmouth Atlas of Children’s Health Care in Northern New England.4 These regions represent markets of pediatric surgical care. Overall, 67.6% of children residing within the areas received tubes from within area providers. In England, rates are reported for residents of Primary Care Trusts (PCT; N=151) that were defined geographically by the NHS. Privately financed procedures are not reported. Observed rates were calculated as the number of procedures divided by the study population within each region.

Calculating expected number of tube insertions

An epidemiological model was developed to estimate “expected” tympanostomy tube placement.16 OME is usually transitory and the expected benefit from ear tubes depends on the time lapsed from onset of diagnosis to when treatment is considered.2,20–25 Our epidemiological model unites two probabilities: age-specific incidence and the disease course of OME. The model starts with the population at risk of developing OME and includes the probability that a relative portion of those at risk will develop bilateral OME with hearing loss of +25dB and +20dB. The recovery rate determines the proportion of children with resolved OME and hearing loss, and so ‘returning’ to the susceptible population. Patients for whom a diagnosis of OME is confirmed after three months of ‘watchful waiting’ have a capacity to benefit (i.e. improvement of hearing) from tympanostomy tubes and should be considered for surgical intervention according to NICE guidance and American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guidelines.1,17 The probabilities are used in a Monte Carlo simulation (i.e. through repeated sampling) to model the expected number of children with capacity to benefit from ear tubes for OME. We calculated expected incidence of bilateral OME with a hearing loss of both +25dB and +20dB with 10,000 iterations of the model to calculate 90% confidence in the mean estimates.

We assume that 46% of children with bilateral OME will have a hearing threshold of +25dB and 35% a hearing threshold of +20dB.16,19 The U.S. AAP guidelines recommend consideration of tympanostomy surgery with a +20dB or greater threshold and the English guidelines recommend surgery for a +25dB or greater threshold.1,17 Both guidelines also suggest tube insertion for children with additional risk factors.

Model validation

The above model parameters and incidence calculations were iteratively discussed and refined in consultation with a Project Steering Group at the London School of Economics and Political Science.16 Participants included experts in audiology, otolaryngology, general practice, and epidemiology, and were invited to validate the model’s components and overall accuracy. The group judged the model to be a judicious representation of the NICE care pathway and treatment process governing OME. The parameters16 were used unchanged in this study.

Analyzing utilization differences

We calculated the difference between observed and expected incidence by geographic area by age. Expected and observed rates were aggregated across age groups, and the total difference was calculated by geographic area. Given that the observed number of PE tubes is based on actual tube placement, the observed counts are the same for each region in the observed to expected ratio while the expected counts differ for 20dB and 25dB hearing loss. We calculated 95% confidence intervals for these ratios assuming 1) a binomial distribution for observed counts and 2) the expected counts as known constants. We used simple linear regression to test the association between rates of observed and expected tube insertions.

This study was approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at Dartmouth College. In England, the use of secondary data in an anonymized and aggregated form does not require ethical approval.

Results

From the administrative data we identified 6,052 tympanostomy tubes provided for children in NNE and 66,414 tubes for children in England over the study period. (Table 1) The mean age of children receiving tympanostomy tubes in NNE and England was 3.9 years old and 4.9 years, respectively and the majority was male (58.5% for NNE; 55.5% for England). The observed rate of tympanostomy tubes provided in England was 4.01 per 1,000 children and 83% higher in NNE at 7.34 per 1,000 person-years.

Table 1.

Study population and characteristics for children ages 2–8 years old who received tympanostomy tubes for treatment of otitis media with effusion.

| Characteristics | England | Northern New England |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Study population (in child-years)1 | 16,511,180 | 824,035 |

| Number of children receiving tube insertions during study period. | 66,414 | 6,052 |

| Children receiving tube insertion: | ||

| Age (mean in years) | 4.9 | 3.9 |

| Sex (% Male) | 55.5 | 58.5 |

| Observed tube insertion rate2 | ||

| All | 4.01 | 7.34 |

| Medicaid | 7.53 | |

| Commercial | 7.16 | |

The total child-years includes children over a four-year study period. English data is for children registered with the NHS and NNE data is limited to children enrolled in Medicaid and reporting commercial insurance plans. This includes 80 % in Maine (2010 Medicaid data was not available), 70% in New Hampshire, and 92 % in Vermont.

Rate per 1,000 child-years.

Regional rates of surgery differed widely in both countries. In NNE, observed incidence varied more than 3-fold across PSAs (3.79 to 13.15 per 1,000), while in England, observed provision of tympanostomy tubes varied more than 30-fold across PCTs (0.45 to 14.45 per 1,000). Using the +25dB threshold, expected incidence for NNE (7.28 to 7.46 per 1,000) and England (7.33 to 7.70 per 1,000) varied little. The +20dB threshold yielded similarly low expected variation for both study areas (NNE: 9.57 to 9.81 per 1,000; England: 9.63 to 10.25 per 1,000). (not shown)

Table 2 presents net differences in expected to observed rates at both hearing thresholds for NNE and England. In NNE, the overall observed total number of insertions was close to the expected number for a +25dB threshold (Observed to Expected difference −7; Observed minus Expected rate −0.01 per thousand; Observed to Expected ratio (O:E) 1.00). Using the +20dB threshold, there were far fewer observed tube insertions than expected (Observed to Expected difference −1,911; Observed minus Expected rate −3.27 per thousand; O:E 0.76). In England, the observed total number of insertions was much lower than expected for both hearing thresholds. Using the +25dB guideline threshold, the Observed to Expected difference was −57,383; Observed minus Expected rate −3.41 per thousand; O:E 0.54. Using the +20dB guideline threshold, the Observed to Expected difference was −96,291; Observed minus Expected rate −5.82 per thousand; O:E 0.41.

Table 2.

Observed and expected tympanostomy tube insertions, by guideline hearing threshold.

| Observed3 | Expected4 | Observed-Expected Difference | Observed-Expected per 1,000 | Observed to Expected ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 dB1 | |||||

| Total NNE | 6,052 | 6,059 | −7 | − 0.01 | 1.00 |

| By Payer: | |||||

| Medicaid | 2,960 | 3,121 | − 161 | −0.19 | 0.95 |

| Commercial | 3,092 | 2,938 | + 154 | + 0.19 | 1.05 |

| Total England | 66,414 | 123,797 | − 57,383 | − 3.41 | 0.54 |

| 20db2 | |||||

| Total NNE | 6,052 | 7,963 | −1,911 | − 3.27 | 0.76 |

| By Payer: | |||||

| Medicaid | 2,960 | 4,102 | −1,142 | −1.39 | 0.72 |

| Commercial | 3,092 | 3,861 | −769 | −0.93 | 0.80 |

| Total England | 66,414 | 162,705 | − 96,291 | − 5.82 | 0.41 |

Hearing threshold guideline recommended by NICE guidance in England.

Hearing threshold guideline recommended by AAP guidance in the US.

Four-year observed number of tympanostomy tubes provided in the study period. These counts are the same for both 20dB and 25 dB observed to expected ratios.

Four-year expected number of tympanostomy tubes provided, estimated by an epidemiological model. (See Appendix)

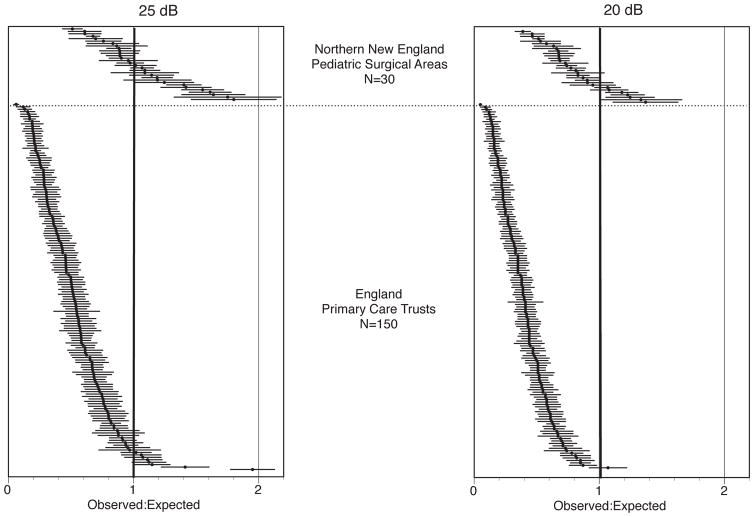

Figure 1 depicts the small area differences in observed to expected incidence centered at a ratio of 1 (i.e. no difference) across NNE and England with 95% confidence intervals. Areas where the number of observed tube insertions exceed expected insertions have O:E ratios > 1 (right) and areas where expected insertions exceed observed have O:E ratios < 1 (left). With a +25dB threshold, the observed incidences were less than expected in all but eight PCTs, while higher than expected rates were observed in about half of the PSAs. With a +20dB threshold, there were fewer than expected in all but two in England and seven NNE areas.

Figure 1.

Ratio of observed to expected number of tympanostomy tubes by regions for 20dB and 20dB hearing thresholds with 95% confidence intervals.

Note: Each dot represents one Pediatric Surgical Area (northern New England) or Primary Care Trust (England). A ratio of 1 indicates that the number of tube insertions equaled the number expected from the model calculating need. Greater than 1 indicated more tube insertions occurred than predicted by the model.

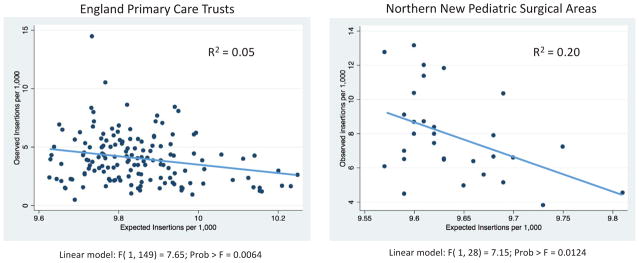

There was a weak inverse relationship (Figure 2) between estimated need of tube insertion and observed rates (England P<0.01 R2=0.05; NNE P<0.05 R2 = 0.20);. Particularly for NNE, areas with relatively higher needs generally had lower observed rates.

Figure 2.

Observed and expected tympanostomy tube insertions per 1,000 across regions of England and Northern New England.

Sensitivity Analyses

While NNE is socio-economically diverse, there are only small differences between rates of tympanostomy procedures between those insured by Medicaid (7.53 per 1,000 person years) and commercial (7.16 per 1,000 per years) insurance plans. (Table 1) There is no equivalent proxy for stratifying by socio-economic risk at the individual level for England.

Discussion

This study confirms previous observations that tympanostomy insertion for OME varies markedly and demonstrates that although England had a lower mean rate than NNE, its variation in rates was much greater.7,8,16 The magnitude of observed variations in procedure rates in both countries is unlikely to be explained by the regional differences in the incidence of OME and raises the question: “Which is the right rate?” Using persistent OME and objective hearing loss as the best evidence-based assessment of likely benefit, this study provides indication of possible underuse in some areas of England and NNE, and possible overuse in other areas of NNE. However, these measures may overestimate the need for tympanostomy tubes insertion for three reasons.

First, the evidence for long-term benefit of tympanostomy tubes is weak. Historically, tympanostomy tube insertion was considered appropriate to prevent recurrent episodes of acute otitis media or for hearing loss from OME.20,21 While OME spontaneously resolves for most children, a proportion suffer from a persistent effusion that may cause hearing loss and, in some children, affect educational performance, language development, and/or behavior.1,32 Tympanostomy tubes for OME have been shown to reduced OME and improve hearing, but longer-term benefits have been harder to detect,14,22–24 particularly with regard to improved language and cognitive development.14,21 Therefore, even guidelines-based assessments of over and under use may overestimate the benefit from tympanostomy tubes.7,8,12,22,24

Second, with the exception of the use of tubes for reducing OME and improvement of hearing loss,25 the three major guidelines are largely based on observational studies and professional opinion.1,17,21 For example, a recent guideline recommends,21 “Clinicians may perform tympanostomy tube insertion in at-risk children with unilateral or bilateral OME that is unlikely to resolve quickly as reflected by a type B (flat) tympanogram or persistence of effusion for 3 months or longer.” At risk children are defined as, “Sensory, physical, cognitive, or behavioral factors that place children who have otitis media with effusion at increased risk for developmental difficulties (delay or disorder).” While, the face validity of these recommendations seems high, the evidence supporting benefit remains limited. Broad definitions of the children likely to benefit adds to the potential for inadvertent overuse and underuse. In the same guidelines, it is recommended that “Clinicians may perform tympanostomy tube insertion in children with unilateral or bilateral OME for 3 months or longer (chronic OME) AND symptoms that are likely attributable to OME that include, but are not limited to, balance (vestibular) problems, poor school performance, behavioral problems, ear discomfort, or reduced quality of life.” The two other current guidelines also suggest consideration of tube placement for at-risk children.1,17 In England, the majority of insertions were recommended on the basis of “exceptional circumstances.”22

Third and finally, audits suggest that many tube insertions may not be appropriate. A multi-center cohort study in New York found that only 7.5% of tympanostomy tubes provided were concordant with clinical practice guidelines.7 In England, a recent multi-center study found that only 32% of ear tubes were in concordance with the NICE criteria.22 In England, epidemiological modeling indicates that about 31,000 children would have benefited from the procedure (25dB threshold), but only about 16,600 operations were undertaken. If the previous clinical audit study is accurate,22 two thirds of those 16,600 were not consistent with guidelines. In NNE, using the U.S. 20dB threshold, about 8,000 children would have benefited from the procedure, but applying the findings of the New York State appropriateness study,7 less than 1,000 of the operations would have been consistent with guidelines.

Taken together, the lack of evidence for long term benefit, the unavailability of clinical trials for the most common indications, and the low level of appropriateness of tube insertions are deeply troubling and raise questions about current utilization patterns. The overall lower rates of PE tube utilization in England likely reflects the greater degree of scrutiny of non-emergent procedures in a national health system with a fixed budget, and England’s more “conservative” clinical practice guidelines. The widespread differences between utilization and estimated need (i.e. expected procedures) indicate that population differences are unlikely to explain variation in use. The magnitude of the variation across both countries regions indicate that differences in country specific insurance systems, reimbursement policies, or the organization of care are unlikely to be dominant factors in explaining the variation. Generally, research into the causes of regional variation into other procedures have found the primary determinant to be differences in physician practice styles reflecting professional uncertainty about the utility of the procedure in a given patient. This is compounded by the difficulty of physicians to diagnose patient and family decision preferences when medical care, watchful waiting, or procedures all have some degree of benefit and risk.26,27,28

Limitations

There are several limitations to the study. The first is the uncertainty of the model parameters. While tympanostomy tube insertion is a common pediatric procedure, many gaps remain in our knowledge of the natural history of OME and the benefit of treatment.29 Population-based prevalence data of OME with hearing loss is not available for small areas, and are impractical to collect. To estimate these rates, we applied historical rates available in the literature to age specific population counts. The model does not include more detailed patient and caregiver characteristics or care preferences. The parameters of the model are therefore estimates of average expected procedures based upon the framework of current objectively-based clinical guidelines. Additional subjective criteria cannot be modeled, such as children with special needs1 or those with behavioral problems without evidence of hearing loss.21 Nevertheless, the quality of evidence (i.e. randomized clinical trials) for tympanostomy tube efficacy is strongest in those with hearing loss demonstrated with audiometry,25 the criteria that we used in this study.

The observed number of tympanostomy tubes is limited to patients insured by Medicaid and commercial plans in NNE. The three states have somewhat different reporting requirements for commercial insurance and some children remain uninsured. Our data capture 92% of the pediatric population of Vermont, 80% of Maine, and about 70% of New Hampshire.4 Maine Medicaid data from 2010 was not available at the time of this study. Observed number of tympanostomy tubes includes only patients treated in the NHS, and not those procedures paid for privately. Although the precise number is not known, the percent of tonsillectomies, a procedure also done by otolaryngologists in both countries, performed in UK private practice is estimated to be about 16% and total private sector expenditure on healthcare in the UK (2011) is 17.2%..30 The lack of private practice data would not substantially affect the results of the study.

While the epidemiological risk for OME is multifactorial, it includes such factors as race, socioeconomic status, exposure to cigarette smoke, and daycare attendance,23,31,32 our model does not fully include information on these patient and environmental characteristics. In NNE, the overall rates of tube placement by insurance type, a socio-economic indicator, differs by only 5%, but this may not be an accurate indicator of the differing incidence of OME. The NNE children are less racially and ethnically diverse than the children of England, but the differences between NNE and England are small compared to NNE and other regions of the U.S.33 Median household income is comparable between nations30,33 Economic diversity in NNE is below the national mean as measured by income inequality.33 The rate of the uninsured population is far below the U.S. average,33 but not as low as in England, where the entire resident population has access to care provided by the NHS. Although waiting times for surgery in the NHS are a perennial concern, for the period of our study, there was a median waiting time of 7.3 weeks (51 days) for tympanostomy tubes from the decision to the actual procedure.34

Conclusion

This study presents a novel comparison of a region of the U.S. and of England in the use of tympanostomy tubes in relation to the number expected from clinical practice guidelines based on persistent OME and objective measures of hearing loss. The observed rates differ markedly across small areas. Given the magnitude of discrepancy from expected rates, the variation is unlikely to be explained by variation in disease prevalence or need. Using our criteria as a standard of practice, these findings suggest that there is overuse and underuse in NNE, and underuse in England. But, as the English and U.S. guidelines differ and the longer-term benefits of tympanostomy tubes for OME have not been demonstrated,23 rates based on guidelines may not be a useful guide of patient need. In this circumstance of uncertainty in benefits, implementation of shared decision making could be a useful companion to clinical practice guidelines by providing balanced information on treatment choices through the use of decision aids, and then in assisting patients and families in clarifying their health values and treatment goals.35–39 Higher quality evidence on the benefits of tympanostomy tubes would also improve the decision making process.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editorial assistance of Julie Doherty.

Funding sources: The Charles H. Hood Foundation, Boston MA and The Health Foundation, London UK (LS, GB). The study sponsors had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, manuscript writing, or decision to publish. No other funding was received to produce the manuscript.

List of abbreviations and acronyms

- NNE

Northern New England

- PSA

Pediatric Surgical Areas

- PCT

Primary Care Trusts

- OME

Otitis media with effusion

- NICE

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence

- NHS

National Health Service

- AAP

American Academy of Pediatrics

- O

E, Observed to Expected

Appendix

Epidemiological Model

This model is explained in more detail in Schang16. Data come from population-based longitudinal studies, stratified by age and cumulative incidence of otitis media. The number of new cases of otitis media in any given year ( N(OME) ) is determined by the annual age-specific cumulative incidence (risk) Ij of OME multiplied by the susceptible population in a given age group Sj, summed over all eligible age groups j (2, 3, 4 … to 8 years). The subgroup of cases with bilateral OME and a given hearing level (20db or 25db) is expressed by

The probability of OME persisting at time t from the onset of OME is modeled as an exponential process of the form

As OME is transitory, the population with capacity to benefit will diminish as time passes since the onset of OME. Population capacity to benefit from ventilation tubes for OME at five months since the onset of OME is estimated as

In calculating the number of children for whom ventilation tubes are expected to be beneficial (by age) and the overall rate of tympanostomy insertion, we can estimate the discrepancy between the number of children for whom ventilation tubes were clinically indicated, based on the criteria of evidence-based clinical guidelines, and the number of children who did and those who did not have tympanostomy insertion. As such, we can make an indicative estimate of both procedure underuse and overuse.

Appendix Table 1.

Tympanostomy Tube Insertion Northern New England

| All rates per 1,000 | 4-year Person years 2 to 8 years, 2007–2010 |

4-year Expected 2007–2010 | Observed 2007–2010 | Observed to Expected Ratio | O:E 95% Cis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for +25 dbHL | for +20 dbHL | 25bB O:E ratio | 20bB O:E ratio | for +25 dbHL | for +20 dbHL | ||||||||

| Pediatric Surgical Areas | Number | Rate | Number | Rate | Number | Rate | upper 95% CI |

lower 95% CI |

upper 95% CI |

lower 95% CI |

|||

| AUGUSTA | 20,558 | 152 | 7.38 | 199 | 9.70 | 135 | 6.57 | 0.890 | 0.677 | 1.040 | 0.740 | 0.791 | 0.563 |

| BANGOR | 39,886 | 295 | 7.41 | 388 | 9.73 | 151 | 3.79 | 0.511 | 0.389 | 0.592 | 0.430 | 0.451 | 0.327 |

| BERLIN | 4,940 | 36 | 7.28 | 47 | 9.57 | 63 | 12.75 | 1.752 | 1.333 | 2.181 | 1.322 | 1.660 | 1.006 |

| BERLIN | 20,189 | 148 | 7.32 | 194 | 9.62 | 169 | 8.37 | 1.144 | 0.870 | 1.316 | 0.972 | 1.001 | 0.740 |

| BRATTLEBORO | 9,299 | 68 | 7.29 | 89 | 9.59 | 65 | 6.99 | 0.958 | 0.729 | 1.190 | 0.726 | 0.906 | 0.552 |

| BRUNSWICK | 20,703 | 152 | 7.32 | 199 | 9.62 | 154 | 7.44 | 1.016 | 0.773 | 1.176 | 0.856 | 0.895 | 0.652 |

| BURLINGTON | 72,838 | 536 | 7.36 | 705 | 9.68 | 573 | 7.87 | 1.068 | 0.813 | 1.156 | 0.981 | 0.879 | 0.747 |

| CONCORD | 41,483 | 303 | 7.30 | 398 | 9.60 | 360 | 8.68 | 1.188 | 0.904 | 1.310 | 1.066 | 0.997 | 0.811 |

| DERRY | 10,528 | 77 | 7.28 | 101 | 9.57 | 64 | 6.08 | 0.835 | 0.635 | 1.038 | 0.631 | 0.790 | 0.480 |

| DOVER | 39,456 | 291 | 7.37 | 382 | 9.69 | 408 | 10.34 | 1.402 | 1.067 | 1.538 | 1.267 | 1.170 | 0.964 |

| ELLSWORTH | 18,046 | 135 | 7.46 | 177 | 9.81 | 82 | 4.54 | 0.609 | 0.463 | 0.741 | 0.478 | 0.563 | 0.363 |

| EXETER | 19,009 | 139 | 7.30 | 182 | 9.60 | 197 | 10.36 | 1.419 | 1.080 | 1.616 | 1.222 | 1.229 | 0.930 |

| KEENE | 13,182 | 96 | 7.32 | 127 | 9.61 | 158 | 11.99 | 1.638 | 1.247 | 1.892 | 1.384 | 1.440 | 1.053 |

| LACONIA | 28,020 | 205 | 7.33 | 270 | 9.63 | 331 | 11.81 | 1.612 | 1.227 | 1.785 | 1.439 | 1.358 | 1.095 |

| LEBANON | 39,609 | 290 | 7.32 | 381 | 9.62 | 316 | 7.98 | 1.090 | 0.830 | 1.210 | 0.971 | 0.921 | 0.739 |

| LEWISTON | 41,410 | 307 | 7.42 | 404 | 9.75 | 299 | 7.22 | 0.973 | 0.741 | 1.083 | 0.864 | 0.824 | 0.657 |

| LITTLETON | 7,236 | 53 | 7.35 | 70 | 9.66 | 46 | 6.36 | 0.865 | 0.658 | 1.115 | 0.616 | 0.848 | 0.469 |

| MANCHESTER | 52,356 | 386 | 7.37 | 507 | 9.68 | 348 | 6.65 | 0.902 | 0.686 | 0.997 | 0.808 | 0.758 | 0.615 |

| MIDDLEBURY | 8,289 | 61 | 7.30 | 80 | 9.60 | 109 | 13.15 | 1.801 | 1.370 | 2.137 | 1.465 | 1.626 | 1.115 |

| NASHUA | 39,997 | 292 | 7.30 | 384 | 9.59 | 260 | 6.50 | 0.891 | 0.678 | 0.999 | 0.783 | 0.760 | 0.596 |

| NEWPORT | 7,537 | 55 | 7.31 | 72 | 9.60 | 60 | 7.96 | 1.090 | 0.829 | 1.364 | 0.815 | 1.038 | 0.620 |

| PORTLAND | 105,483 | 774 | 7.34 | 1,017 | 9.65 | 523 | 4.96 | 0.676 | 0.514 | 0.733 | 0.618 | 0.558 | 0.470 |

| PRESQUE ISLE | 20,839 | 152 | 7.30 | 200 | 9.59 | 93 | 4.46 | 0.611 | 0.465 | 0.735 | 0.487 | 0.560 | 0.371 |

| ROCKLAND | 18,797 | 138 | 7.36 | 182 | 9.67 | 105 | 5.59 | 0.759 | 0.578 | 0.904 | 0.614 | 0.688 | 0.467 |

| RUTLAND | 28,469 | 208 | 7.31 | 274 | 9.61 | 323 | 11.35 | 1.552 | 1.181 | 1.720 | 1.383 | 1.309 | 1.053 |

| SANFORD | 17,794 | 130 | 7.33 | 171 | 9.63 | 116 | 6.52 | 0.889 | 0.677 | 1.051 | 0.728 | 0.800 | 0.554 |

| SPRINGFIELD | 8,503 | 62 | 7.31 | 82 | 9.61 | 74 | 8.70 | 1.191 | 0.906 | 1.461 | 0.920 | 1.111 | 0.700 |

| ST JOHNSBURY | 8,177 | 60 | 7.37 | 79 | 9.69 | 42 | 5.14 | 0.697 | 0.530 | 0.907 | 0.487 | 0.690 | 0.370 |

| WATERVILLE | 49,745 | 365 | 7.33 | 479 | 9.63 | 322 | 6.47 | 0.883 | 0.672 | 0.979 | 0.787 | 0.745 | 0.599 |

| YORK | 11,661 | 85 | 7.29 | 112 | 9.59 | 106 | 9.09 | 1.246 | 0.948 | 1.483 | 1.010 | 1.128 | 0.769 |

| Total | 824,035 | 6,051 | 7.34 | 7,953 | 9.7 | 6,052 | 7.34 | 1.000 | 0.761 | ||||

Appendix Table 2.

Tympanostomy Tube Insertion England

| All rates per 1,000 | Population 2 to 8 years, 2007–2010 |

Expected 2007–2010 (annual average) | Observed 2007–2010 (annual average) |

Observed to Expected Ratio | O:E 95% CIs | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for +25 dbHL | for +20 dbHL | 25bB O:E ratio | 20 dB O:E ratio | for +25 dbHL | for +20 dbHL | ||||||||

| Primary Care Trust | Number | Rate | Number | Rate | Number | Rate | upper 95% CI |

lower 95% CI |

upper 95% CI |

lower 95% CI |

|||

| Ashton, Leigh and Wigan | 24,590 | 184 | 7.5 | 242 | 9.8 | 120 | 4.88 | 0.653 | 0.497 | 0.769 | 0.536 | 0.585 | 0.408 |

| Barking and Dagenham | 19,028 | 147 | 7.7 | 193 | 10.2 | 29 | 1.50 | 0.194 | 0.148 | 0.265 | 0.123 | 0.202 | 0.093 |

| Barnet | 30,665 | 231 | 7.5 | 304 | 9.9 | 45 | 1.45 | 0.193 | 0.147 | 0.249 | 0.136 | 0.190 | 0.104 |

| Barnsley | 17,658 | 132 | 7.5 | 174 | 9.8 | 86 | 4.87 | 0.650 | 0.495 | 0.788 | 0.513 | 0.599 | 0.391 |

| Bassetlaw | 8,218 | 61 | 7.4 | 80 | 9.7 | 59 | 7.18 | 0.969 | 0.737 | 1.215 | 0.722 | 0.925 | 0.550 |

| Bath and North East Somerset | 12,457 | 92 | 7.4 | 121 | 9.7 | 28 | 2.25 | 0.305 | 0.232 | 0.418 | 0.192 | 0.318 | 0.146 |

| Bedfordshire | 34,556 | 257 | 7.4 | 337 | 9.8 | 153 | 4.43 | 0.596 | 0.454 | 0.691 | 0.502 | 0.525 | 0.382 |

| Berkshire East | 34,555 | 261 | 7.5 | 343 | 9.9 | 119 | 3.44 | 0.457 | 0.347 | 0.538 | 0.375 | 0.410 | 0.285 |

| Berkshire West | 38,620 | 290 | 7.5 | 381 | 9.9 | 157 | 4.07 | 0.541 | 0.412 | 0.626 | 0.457 | 0.476 | 0.347 |

| Bexley | 19,176 | 143 | 7.5 | 188 | 9.8 | 40 | 2.09 | 0.280 | 0.213 | 0.366 | 0.193 | 0.279 | 0.147 |

| Birmingham East and North | 41,127 | 310 | 7.5 | 407 | 9.9 | 157 | 3.82 | 0.506 | 0.385 | 0.585 | 0.427 | 0.445 | 0.325 |

| Blackburn with Darwen Teaching | 14,657 | 110 | 7.5 | 144 | 9.8 | 62 | 4.20 | 0.562 | 0.427 | 0.702 | 0.421 | 0.534 | 0.321 |

| Blackpool | 10,727 | 80 | 7.5 | 105 | 9.8 | 46 | 4.29 | 0.573 | 0.436 | 0.738 | 0.408 | 0.562 | 0.310 |

| Bolton Teaching | 23,502 | 176 | 7.5 | 231 | 9.8 | 81 | 3.43 | 0.457 | 0.348 | 0.557 | 0.357 | 0.424 | 0.272 |

| Bournemouth and Poole Teaching | 21,001 | 158 | 7.5 | 207 | 9.9 | 79 | 3.76 | 0.501 | 0.381 | 0.612 | 0.391 | 0.465 | 0.297 |

| Bradford and Airedale Teaching | 50,745 | 383 | 7.6 | 504 | 9.9 | 264 | 5.20 | 0.688 | 0.524 | 0.771 | 0.606 | 0.587 | 0.461 |

| Brent Teaching | 23,538 | 183 | 7.8 | 240 | 10.2 | 40 | 1.68 | 0.216 | 0.164 | 0.283 | 0.149 | 0.216 | 0.113 |

| Brighton and Hove City | 17,914 | 135 | 7.6 | 178 | 9.9 | 78 | 4.33 | 0.573 | 0.436 | 0.700 | 0.445 | 0.532 | 0.339 |

| Bristol | 31,406 | 239 | 7.6 | 315 | 10.0 | 97 | 3.09 | 0.405 | 0.308 | 0.486 | 0.325 | 0.370 | 0.247 |

| Bromley | 26,152 | 194 | 7.4 | 255 | 9.8 | 105 | 4.02 | 0.540 | 0.411 | 0.643 | 0.437 | 0.490 | 0.333 |

| Buckinghamshire | 44,918 | 330 | 7.3 | 434 | 9.7 | 159 | 3.54 | 0.482 | 0.367 | 0.557 | 0.407 | 0.423 | 0.310 |

| Bury | 15,727 | 117 | 7.5 | 154 | 9.8 | 72 | 4.58 | 0.613 | 0.466 | 0.754 | 0.472 | 0.574 | 0.359 |

| Calderdale | 17,159 | 128 | 7.5 | 169 | 9.8 | 98 | 5.68 | 0.760 | 0.578 | 0.910 | 0.609 | 0.692 | 0.464 |

| Cambridgeshire | 47,209 | 351 | 7.4 | 461 | 9.8 | 204 | 4.32 | 0.582 | 0.443 | 0.661 | 0.502 | 0.503 | 0.382 |

| Camden | 16,415 | 124 | 7.6 | 163 | 10.0 | 21 | 1.28 | 0.169 | 0.128 | 0.241 | 0.097 | 0.183 | 0.074 |

| Central and Eastern Cheshire | 35,337 | 261 | 7.4 | 344 | 9.7 | 137 | 3.86 | 0.522 | 0.397 | 0.609 | 0.435 | 0.464 | 0.331 |

| Central Lancashire | 35,959 | 269 | 7.5 | 353 | 9.8 | 138 | 3.84 | 0.513 | 0.391 | 0.599 | 0.428 | 0.456 | 0.326 |

| City and Hackney Teaching | 22,414 | 173 | 7.7 | 228 | 10.2 | 27 | 1.18 | 0.153 | 0.116 | 0.211 | 0.095 | 0.161 | 0.072 |

| Cornwall and Isles of Scilly | 37,292 | 274 | 7.3 | 359 | 9.6 | 187 | 5.01 | 0.684 | 0.520 | 0.781 | 0.586 | 0.595 | 0.446 |

| County Durham | 36,930 | 275 | 7.5 | 362 | 9.8 | 232 | 6.28 | 0.843 | 0.641 | 0.951 | 0.735 | 0.723 | 0.559 |

| Coventry Teaching | 25,797 | 195 | 7.6 | 256 | 9.9 | 110 | 4.24 | 0.561 | 0.427 | 0.666 | 0.456 | 0.507 | 0.347 |

| Croydon | 30,581 | 231 | 7.5 | 303 | 9.9 | 72 | 2.35 | 0.312 | 0.238 | 0.384 | 0.240 | 0.292 | 0.183 |

| Cumbria Teaching | 34,669 | 256 | 7.4 | 336 | 9.7 | 216 | 6.23 | 0.844 | 0.642 | 0.956 | 0.732 | 0.727 | 0.557 |

| Darlington | 8,312 | 62 | 7.5 | 82 | 9.9 | 34 | 4.09 | 0.545 | 0.415 | 0.728 | 0.362 | 0.554 | 0.276 |

| Derby City | 20,048 | 151 | 7.5 | 198 | 9.9 | 119 | 5.94 | 0.789 | 0.600 | 0.930 | 0.648 | 0.708 | 0.493 |

| Derbyshire County | 53,933 | 399 | 7.4 | 524 | 9.7 | 232 | 4.30 | 0.582 | 0.443 | 0.657 | 0.507 | 0.500 | 0.386 |

| Devon | 51,396 | 377 | 7.3 | 496 | 9.7 | 354 | 6.89 | 0.938 | 0.714 | 1.035 | 0.841 | 0.788 | 0.640 |

| Doncaster | 23,489 | 175 | 7.5 | 230 | 9.8 | 124 | 5.28 | 0.707 | 0.538 | 0.831 | 0.583 | 0.633 | 0.444 |

| Dorset | 27,413 | 201 | 7.3 | 264 | 9.6 | 66 | 2.39 | 0.326 | 0.248 | 0.405 | 0.247 | 0.308 | 0.188 |

| Dudley | 24,365 | 181 | 7.4 | 238 | 9.8 | 135 | 5.54 | 0.745 | 0.567 | 0.871 | 0.620 | 0.663 | 0.472 |

| Ealing | 27,174 | 210 | 7.7 | 276 | 10.1 | 42 | 1.55 | 0.200 | 0.152 | 0.261 | 0.140 | 0.199 | 0.106 |

| East Lancashire Teaching | 32,177 | 238 | 7.4 | 313 | 9.7 | 465 | 14.45 | 1.951 | 1.485 | 2.127 | 1.775 | 1.619 | 1.351 |

| East Riding of Yorkshire | 25,693 | 189 | 7.4 | 249 | 9.7 | 144 | 5.60 | 0.760 | 0.578 | 0.884 | 0.636 | 0.673 | 0.484 |

| East Sussex Downs and Weald | 24,318 | 178 | 7.3 | 234 | 9.6 | 95 | 3.91 | 0.533 | 0.406 | 0.640 | 0.426 | 0.487 | 0.324 |

| Eastern and Coastal Kent | 48,493 | 358 | 7.4 | 471 | 9.7 | 132 | 2.71 | 0.367 | 0.279 | 0.429 | 0.304 | 0.327 | 0.231 |

| Enfield | 35,288 | 266 | 7.5 | 349 | 9.9 | 271 | 7.68 | 1.020 | 0.776 | 1.141 | 0.899 | 0.868 | 0.684 |

| Gateshead | 18,147 | 136 | 7.5 | 179 | 9.9 | 48 | 2.62 | 0.349 | 0.266 | 0.448 | 0.250 | 0.341 | 0.190 |

| Gloucestershire | 37,128 | 273 | 7.3 | 359 | 9.7 | 77 | 2.06 | 0.280 | 0.213 | 0.343 | 0.218 | 0.261 | 0.166 |

| Great Yarmouth and Waveney | 22,709 | 169 | 7.4 | 222 | 9.8 | 130 | 5.72 | 0.771 | 0.587 | 0.903 | 0.639 | 0.687 | 0.486 |

| Greenwich Teaching | 19,740 | 151 | 7.7 | 199 | 10.1 | 86 | 4.33 | 0.566 | 0.431 | 0.686 | 0.446 | 0.522 | 0.340 |

| Halton and St Helens | 23,827 | 179 | 7.5 | 235 | 9.9 | 51 | 2.14 | 0.285 | 0.217 | 0.363 | 0.207 | 0.276 | 0.157 |

| Hammersmith and Fulham | 15,833 | 120 | 7.6 | 158 | 10.0 | 96 | 6.06 | 0.798 | 0.607 | 0.957 | 0.639 | 0.728 | 0.486 |

| Hampshire | 79,497 | 586 | 7.4 | 770 | 9.7 | 36 | 0.45 | 0.061 | 0.047 | 0.081 | 0.041 | 0.062 | 0.031 |

| Haringey Teaching | 41,148 | 311 | 7.6 | 409 | 9.9 | 346 | 8.41 | 1.112 | 0.846 | 1.228 | 0.995 | 0.934 | 0.757 |

| Harrow | 19,617 | 149 | 7.6 | 196 | 10.0 | 18 | 0.89 | 0.117 | 0.089 | 0.172 | 0.062 | 0.131 | 0.047 |

| Hartlepool | 10,786 | 81 | 7.5 | 106 | 9.9 | 18 | 1.62 | 0.216 | 0.165 | 0.318 | 0.115 | 0.242 | 0.088 |

| Hastings and Rother | 11,403 | 84 | 7.4 | 110 | 9.7 | 25 | 2.19 | 0.298 | 0.226 | 0.414 | 0.181 | 0.315 | 0.138 |

| Havering | 16,833 | 125 | 7.4 | 164 | 9.7 | 50 | 2.94 | 0.397 | 0.302 | 0.507 | 0.286 | 0.386 | 0.218 |

| Heart of Birmingham Teaching | 27,867 | 211 | 7.6 | 278 | 10.0 | 40 | 1.44 | 0.189 | 0.144 | 0.248 | 0.131 | 0.189 | 0.099 |

| Herefordshire | 17,538 | 130 | 7.4 | 171 | 9.8 | 89 | 5.07 | 0.683 | 0.520 | 0.825 | 0.542 | 0.628 | 0.412 |

| Hertfordshire (PCTs East and North; West Hert | 72,470 | 539 | 7.4 | 708 | 9.8 | 117 | 1.61 | 0.217 | 0.165 | 0.257 | 0.178 | 0.195 | 0.135 |

| Heywood, Middleton and Rochdale | 37,900 | 284 | 7.5 | 374 | 9.9 | 48 | 1.27 | 0.169 | 0.129 | 0.217 | 0.121 | 0.165 | 0.092 |

| Hillingdon | 21,929 | 165 | 7.5 | 217 | 9.9 | 42 | 1.89 | 0.251 | 0.191 | 0.327 | 0.175 | 0.249 | 0.133 |

| Hounslow | 21,237 | 164 | 7.7 | 215 | 10.1 | 50 | 2.33 | 0.303 | 0.230 | 0.387 | 0.218 | 0.294 | 0.166 |

| Hull Teaching | 20,146 | 153 | 7.6 | 201 | 10.0 | 125 | 6.20 | 0.816 | 0.621 | 0.958 | 0.673 | 0.729 | 0.512 |

| Isle of Wight National Health Service | 12,047 | 90 | 7.5 | 118 | 9.8 | 26 | 2.16 | 0.290 | 0.220 | 0.401 | 0.178 | 0.305 | 0.136 |

| Islington | 12,410 | 95 | 7.6 | 124 | 10.0 | 23 | 1.85 | 0.243 | 0.185 | 0.343 | 0.144 | 0.261 | 0.110 |

| Kensington and Chelsea | 12,993 | 97 | 7.5 | 128 | 9.8 | 19 | 1.42 | 0.190 | 0.145 | 0.277 | 0.103 | 0.210 | 0.079 |

| Kingston | 12,885 | 97 | 7.5 | 127 | 9.9 | 66 | 5.08 | 0.676 | 0.514 | 0.839 | 0.513 | 0.638 | 0.390 |

| Kirklees | 30,182 | 226 | 7.5 | 297 | 9.8 | 171 | 5.67 | 0.756 | 0.575 | 0.869 | 0.643 | 0.661 | 0.489 |

| Knowsley | 18,760 | 140 | 7.5 | 184 | 9.8 | 56 | 2.99 | 0.399 | 0.304 | 0.503 | 0.295 | 0.383 | 0.224 |

| Lambeth | 20,160 | 156 | 7.7 | 205 | 10.2 | 25 | 1.24 | 0.161 | 0.122 | 0.223 | 0.098 | 0.170 | 0.074 |

| Leeds | 47,841 | 360 | 7.5 | 473 | 9.9 | 279 | 5.83 | 0.775 | 0.590 | 0.866 | 0.684 | 0.659 | 0.521 |

| Leicester City | 35,409 | 269 | 7.6 | 354 | 10.0 | 156 | 4.41 | 0.580 | 0.441 | 0.670 | 0.489 | 0.510 | 0.372 |

| Leicestershire County and Rutland | 46,092 | 341 | 7.4 | 449 | 9.7 | 310 | 6.73 | 0.908 | 0.691 | 1.009 | 0.807 | 0.767 | 0.614 |

| Lewisham | 30,527 | 231 | 7.6 | 303 | 9.9 | 55 | 1.79 | 0.236 | 0.180 | 0.299 | 0.173 | 0.227 | 0.132 |

| Lincolnshire Teaching | 43,198 | 320 | 7.4 | 420 | 9.7 | 214 | 4.95 | 0.669 | 0.509 | 0.759 | 0.580 | 0.577 | 0.441 |

| Liverpool | 36,432 | 273 | 7.5 | 359 | 9.9 | 98 | 2.69 | 0.359 | 0.273 | 0.430 | 0.288 | 0.327 | 0.219 |

| Luton | 22,492 | 171 | 7.6 | 225 | 10.0 | 87 | 3.85 | 0.505 | 0.384 | 0.611 | 0.399 | 0.465 | 0.303 |

| Manchester Teaching | 33,141 | 256 | 7.7 | 336 | 10.1 | 140 | 4.22 | 0.547 | 0.417 | 0.638 | 0.457 | 0.485 | 0.348 |

| Medway | 26,516 | 200 | 7.5 | 263 | 9.9 | 93 | 3.49 | 0.463 | 0.352 | 0.557 | 0.369 | 0.424 | 0.281 |

| Mid Essex | 28,169 | 208 | 7.4 | 274 | 9.7 | 149 | 5.29 | 0.715 | 0.544 | 0.830 | 0.601 | 0.632 | 0.457 |

| Middlesbrough | 16,463 | 123 | 7.5 | 162 | 9.8 | 57 | 3.43 | 0.458 | 0.349 | 0.578 | 0.339 | 0.440 | 0.258 |

| Milton Keynes | 19,847 | 150 | 7.5 | 197 | 9.9 | 100 | 5.04 | 0.668 | 0.509 | 0.799 | 0.538 | 0.608 | 0.409 |

| Newcastle | 20,488 | 154 | 7.5 | 202 | 9.9 | 96 | 4.69 | 0.624 | 0.475 | 0.749 | 0.500 | 0.570 | 0.380 |

| Newham | 25,195 | 196 | 7.8 | 257 | 10.2 | 74 | 2.94 | 0.378 | 0.288 | 0.465 | 0.292 | 0.353 | 0.222 |

| Norfolk | 46,473 | 346 | 7.5 | 455 | 9.8 | 241 | 5.19 | 0.696 | 0.530 | 0.784 | 0.608 | 0.596 | 0.463 |

| North East Essex | 30,659 | 227 | 7.4 | 298 | 9.7 | 114 | 3.70 | 0.500 | 0.380 | 0.592 | 0.408 | 0.450 | 0.310 |

| North East Lincolnshire | 15,379 | 115 | 7.4 | 151 | 9.8 | 33 | 2.11 | 0.284 | 0.216 | 0.381 | 0.186 | 0.290 | 0.142 |

| North Lancashire Teaching | 19,517 | 143 | 7.3 | 188 | 9.6 | 84 | 4.28 | 0.584 | 0.444 | 0.709 | 0.459 | 0.539 | 0.349 |

| North Lincolnshire | 14,656 | 109 | 7.4 | 143 | 9.8 | 33 | 2.25 | 0.303 | 0.230 | 0.406 | 0.200 | 0.309 | 0.152 |

| North Somerset | 15,102 | 112 | 7.4 | 147 | 9.7 | 47 | 3.11 | 0.421 | 0.320 | 0.541 | 0.301 | 0.411 | 0.229 |

| North Staffordshire | 15,371 | 113 | 7.4 | 149 | 9.7 | 22 | 1.43 | 0.195 | 0.148 | 0.276 | 0.113 | 0.210 | 0.086 |

| North Tyneside | 14,820 | 111 | 7.5 | 146 | 9.8 | 97 | 6.51 | 0.871 | 0.662 | 1.044 | 0.697 | 0.794 | 0.531 |

| North Yorkshire and York | 45,510 | 336 | 7.4 | 442 | 9.7 | 120 | 2.64 | 0.357 | 0.271 | 0.420 | 0.293 | 0.320 | 0.223 |

| Northamptonshire Teaching | 57,534 | 428 | 7.4 | 563 | 9.8 | 288 | 5.01 | 0.673 | 0.512 | 0.750 | 0.595 | 0.571 | 0.453 |

| Northumberland | 31,739 | 235 | 7.4 | 309 | 9.7 | 264 | 8.32 | 1.123 | 0.855 | 1.258 | 0.988 | 0.957 | 0.752 |

| Nottingham City | 21,519 | 163 | 7.6 | 214 | 10.0 | 173 | 8.04 | 1.062 | 0.808 | 1.219 | 0.904 | 0.928 | 0.688 |

| Nottinghamshire County Teaching | 42,661 | 317 | 7.4 | 417 | 9.8 | 91 | 2.12 | 0.285 | 0.217 | 0.344 | 0.226 | 0.262 | 0.172 |

| Oldham | 28,553 | 213 | 7.5 | 280 | 9.8 | 245 | 8.58 | 1.148 | 0.874 | 1.291 | 1.005 | 0.983 | 0.765 |

| Oxfordshire | 41,870 | 313 | 7.5 | 411 | 9.8 | 102 | 2.44 | 0.326 | 0.248 | 0.389 | 0.263 | 0.296 | 0.200 |

| Peterborough | 24,121 | 182 | 7.5 | 239 | 9.9 | 170 | 7.05 | 0.935 | 0.711 | 1.075 | 0.795 | 0.818 | 0.605 |

| Plymouth Teaching | 17,743 | 134 | 7.6 | 176 | 9.9 | 42 | 2.34 | 0.310 | 0.236 | 0.404 | 0.216 | 0.307 | 0.164 |

| Portsmouth City Teaching | 15,601 | 117 | 7.5 | 154 | 9.9 | 112 | 7.18 | 0.954 | 0.726 | 1.130 | 0.778 | 0.859 | 0.592 |

| Redbridge | 22,203 | 168 | 7.6 | 221 | 9.9 | 43 | 1.94 | 0.256 | 0.195 | 0.333 | 0.180 | 0.253 | 0.137 |

| Redcar and Cleveland | 14,654 | 109 | 7.4 | 143 | 9.8 | 61 | 4.16 | 0.559 | 0.425 | 0.699 | 0.419 | 0.532 | 0.319 |

| Richmond and Twickenham | 15,170 | 113 | 7.4 | 148 | 9.8 | 49 | 3.23 | 0.434 | 0.330 | 0.555 | 0.312 | 0.422 | 0.238 |

| Rotherham | 19,653 | 146 | 7.4 | 192 | 9.8 | 42 | 2.11 | 0.284 | 0.216 | 0.370 | 0.198 | 0.282 | 0.150 |

| Salford | 18,096 | 137 | 7.6 | 180 | 10.0 | 53 | 2.93 | 0.386 | 0.294 | 0.490 | 0.282 | 0.373 | 0.215 |

| Sandwell | 24,242 | 183 | 7.6 | 241 | 9.9 | 66 | 2.72 | 0.360 | 0.274 | 0.447 | 0.273 | 0.340 | 0.208 |

| Sefton | 21,661 | 161 | 7.4 | 211 | 9.8 | 62 | 2.84 | 0.382 | 0.291 | 0.478 | 0.287 | 0.363 | 0.218 |

| Sheffield | 34,390 | 257 | 7.5 | 338 | 9.8 | 59 | 1.72 | 0.229 | 0.174 | 0.288 | 0.171 | 0.219 | 0.130 |

| Shropshire County | 26,001 | 193 | 7.4 | 253 | 9.7 | 207 | 7.96 | 1.075 | 0.818 | 1.220 | 0.929 | 0.929 | 0.707 |

| Solihull | 17,348 | 128 | 7.4 | 168 | 9.7 | 112 | 6.46 | 0.878 | 0.668 | 1.041 | 0.716 | 0.792 | 0.545 |

| Somerset | 32,906 | 242 | 7.4 | 318 | 9.7 | 50 | 1.50 | 0.205 | 0.156 | 0.261 | 0.148 | 0.199 | 0.112 |

| South Birmingham | 29,896 | 224 | 7.5 | 295 | 9.9 | 162 | 5.42 | 0.722 | 0.550 | 0.833 | 0.611 | 0.634 | 0.465 |

| South East Essex | 26,653 | 198 | 7.4 | 261 | 9.8 | 159 | 5.97 | 0.801 | 0.609 | 0.925 | 0.677 | 0.704 | 0.515 |

| South Gloucestershire | 21,942 | 162 | 7.4 | 213 | 9.7 | 75 | 3.40 | 0.459 | 0.349 | 0.563 | 0.355 | 0.428 | 0.270 |

| South Staffordshire | 39,796 | 294 | 7.4 | 386 | 9.7 | 61 | 1.53 | 0.207 | 0.158 | 0.259 | 0.155 | 0.197 | 0.118 |

| South Tyneside | 19,724 | 147 | 7.4 | 193 | 9.8 | 207 | 10.50 | 1.412 | 1.074 | 1.604 | 1.221 | 1.220 | 0.929 |

| South West Essex | 28,837 | 215 | 7.5 | 283 | 9.8 | 68 | 2.36 | 0.316 | 0.241 | 0.391 | 0.241 | 0.298 | 0.183 |

| Southampton City | 20,999 | 159 | 7.6 | 209 | 9.9 | 127 | 6.05 | 0.800 | 0.609 | 0.939 | 0.661 | 0.714 | 0.503 |

| Southwark | 21,205 | 165 | 7.8 | 217 | 10.2 | 34 | 1.60 | 0.206 | 0.157 | 0.275 | 0.137 | 0.209 | 0.104 |

| Stockport | 22,557 | 169 | 7.5 | 222 | 9.8 | 22 | 0.98 | 0.130 | 0.099 | 0.185 | 0.076 | 0.141 | 0.058 |

| Stockton-on-Tees Teaching (PCT North Tees) | 17,089 | 128 | 7.5 | 168 | 9.8 | 93 | 5.44 | 0.729 | 0.555 | 0.877 | 0.581 | 0.667 | 0.442 |

| Stoke on Trent | 18,945 | 143 | 7.6 | 188 | 9.9 | 61 | 3.19 | 0.423 | 0.322 | 0.529 | 0.316 | 0.403 | 0.241 |

| Suffolk | 40,633 | 303 | 7.5 | 398 | 9.8 | 277 | 6.82 | 0.914 | 0.696 | 1.021 | 0.807 | 0.777 | 0.614 |

| Sunderland Teaching | 27,429 | 204 | 7.5 | 269 | 9.8 | 94 | 3.43 | 0.460 | 0.350 | 0.553 | 0.367 | 0.420 | 0.279 |

| Surrey | 73,089 | 543 | 7.4 | 713 | 9.8 | 446 | 6.10 | 0.822 | 0.625 | 0.898 | 0.746 | 0.683 | 0.567 |

| Sutton and Merton | 48,006 | 360 | 7.5 | 473 | 9.9 | 95 | 1.97 | 0.262 | 0.200 | 0.315 | 0.210 | 0.240 | 0.159 |

| Swindon | 21,459 | 163 | 7.6 | 214 | 10.0 | 33 | 1.54 | 0.203 | 0.154 | 0.272 | 0.134 | 0.207 | 0.102 |

| Tameside and Glossop | 19,620 | 147 | 7.5 | 193 | 9.8 | 79 | 4.03 | 0.537 | 0.409 | 0.656 | 0.419 | 0.499 | 0.319 |

| Telford and Wrekin | 15,765 | 118 | 7.5 | 155 | 9.8 | 88 | 5.58 | 0.748 | 0.569 | 0.904 | 0.592 | 0.688 | 0.451 |

| Torbay | 10,401 | 77 | 7.4 | 102 | 9.8 | 68 | 6.54 | 0.878 | 0.668 | 1.086 | 0.670 | 0.826 | 0.510 |

| Tower Hamlets | 17,958 | 138 | 7.7 | 182 | 10.1 | 72 | 3.98 | 0.517 | 0.394 | 0.637 | 0.398 | 0.485 | 0.303 |

| Trafford | 19,392 | 146 | 7.5 | 192 | 9.9 | 90 | 4.62 | 0.614 | 0.467 | 0.741 | 0.487 | 0.564 | 0.371 |

| Wakefield District | 23,506 | 175 | 7.4 | 230 | 9.8 | 76 | 3.21 | 0.432 | 0.329 | 0.529 | 0.335 | 0.403 | 0.255 |

| Walsall Teaching | 23,499 | 176 | 7.5 | 231 | 9.8 | 88 | 3.72 | 0.498 | 0.379 | 0.602 | 0.394 | 0.458 | 0.300 |

| Waltham Forest | 22,069 | 169 | 7.7 | 223 | 10.1 | 48 | 2.15 | 0.280 | 0.213 | 0.360 | 0.201 | 0.274 | 0.153 |

| Wandsworth | 22,052 | 172 | 7.8 | 226 | 10.2 | 57 | 2.58 | 0.331 | 0.252 | 0.417 | 0.246 | 0.318 | 0.187 |

| Warrington | 17,896 | 134 | 7.5 | 177 | 9.9 | 62 | 3.46 | 0.461 | 0.351 | 0.576 | 0.347 | 0.438 | 0.264 |

| Warwickshire | 34,692 | 257 | 7.4 | 337 | 9.7 | 135 | 3.89 | 0.526 | 0.400 | 0.615 | 0.438 | 0.468 | 0.333 |

| West Essex | 28,160 | 209 | 7.4 | 275 | 9.8 | 95 | 3.37 | 0.454 | 0.346 | 0.545 | 0.363 | 0.415 | 0.276 |

| West Kent | 48,555 | 360 | 7.4 | 474 | 9.8 | 241 | 4.96 | 0.669 | 0.509 | 0.753 | 0.584 | 0.573 | 0.445 |

| West Sussex | 59,676 | 441 | 7.4 | 580 | 9.7 | 270 | 4.52 | 0.612 | 0.466 | 0.685 | 0.539 | 0.521 | 0.410 |

| Western Cheshire | 28,231 | 209 | 7.4 | 275 | 9.8 | 90 | 3.19 | 0.430 | 0.327 | 0.518 | 0.341 | 0.394 | 0.259 |

| Westminster | 15,265 | 116 | 7.6 | 152 | 10.0 | 29 | 1.90 | 0.250 | 0.190 | 0.341 | 0.159 | 0.260 | 0.121 |

| Wiltshire | 31,893 | 234 | 7.3 | 308 | 9.6 | 72 | 2.26 | 0.308 | 0.234 | 0.379 | 0.237 | 0.288 | 0.180 |

| Wirral | 27,820 | 207 | 7.4 | 272 | 9.8 | 120 | 4.30 | 0.578 | 0.440 | 0.682 | 0.475 | 0.519 | 0.361 |

| Wolverhampton City | 21,186 | 159 | 7.5 | 209 | 9.9 | 82 | 3.85 | 0.511 | 0.389 | 0.622 | 0.401 | 0.473 | 0.305 |

| Worcestershire | 36,964 | 274 | 7.4 | 360 | 9.8 | 151 | 4.09 | 0.551 | 0.419 | 0.638 | 0.463 | 0.486 | 0.352 |

| 1 year numbers and rates per 1,000 | 4,137,795 | 30,949 | 7.4 | 40,676 | 9.8 | 16,604 | 4.01 | 3.36 | |||||

| 4 year | 16,551,180 | ||||||||||||

Footnotes

Devin Parker wrote the first draft of the manuscript.

Financial Disclosure Statement: All authors have no additional financial relationships to report.

Conflict of Interest Statement: All authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Otitis Media With Effusion. Otitis Media With Effusion. J Pediatr. 2004;113:1412–1429. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.5.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zielhuis GA, Rach GH, Van den Broek P. The occurrence of otitis media with effusion in Dutch pre-school children. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1990;15:147–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1990.tb00448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schappert SM. Office visits for otitis media: United States, 1975–90. Adv Data. 1992;(214):1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodman DC, Morden NE, Ralston SL, Chang CH, Parker DM, Weinstein SJ, Bronner KK. The Dartmouth Atlas of Children’s Health Care in Northern New England. Hanover, NH: The Trustees of Dartmouth College; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haapkyla J, Karevold G, Kvaerner KJ, Pitkaranta A. Finnish adenoidectomy and tympanostomy rates in children; national variation. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;70:1569–1573. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karevold G, Haapkyla J, Pitkaranta A, Nafstad P, Kvaerner KJ. Paediatric otitis media surgery in Norway. Acta Oto-Laryngologica. 2007;127:29–33. doi: 10.1080/00016480600606756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keyhani S, Kleinman LC, Rothschild M, Bernstein JM, Anderson R, Chassin M. Overuse of tympanostomy tubes in New York metropolitan area: evidence from five hospital cohort. BMJ. 2008;337:a1607. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleinman LC, Kosecoff J, Dubois RW, Brook RH. The medical appropriateness of tympanostomy tubes proposed for children younger than 16 years in the United States. JAMA. 1994;271:1250–1255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wennberg JE, et al. The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. Chicago, IL: American Hospital Publishing; 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karevold G, Haapkyla J, Pitkaranta A, Nafstad P, Kvaerner KJ. Paediatric otitis media surgery in Norway. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007;127:29–33. doi: 10.1080/00016480600606756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wennberg JE, et al. The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care in Michigan. Hanover, NH: The Trustees of Dartmouth College; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Black N. Geographical Variations in use of surgery for glue ear. J R Soc Med. 1985;78:641–648. doi: 10.1177/014107688507800809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garner S, Littlejohns P. Disinvestment from low value clinical interventions: NICEly done? BMJ. 2011;343:d4519. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rovers MM, Straatman H, Ingels K, van der Wilt GJ, van den Broek P, Zielhuis GA. The effect of ventilation tubes on language development in infants with otitis media with effusion: A randomized trial. J Pediatr. 2000;106:E42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schilder AG, Lok W, Rovers MM. International perspectives on management of acute otitis media: a qualitative review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;68:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schang L, De Poli C, Airoldi M, Morton A, Bohm N, Lakhanpaul M, et al. Using an epidemiological model to investigate unwarranted variation: the case of ventilation tubes for otitis media with effusion in England. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2014;19:236–244. doi: 10.1177/1355819614536886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Surgical management of children with otitis media with effusion (OME) Clinical Guidelines CG60. London, UK: The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weinstein SJ, House SA, Chang CH, Wasserman JR, Goodman DC, Morden NE. Small geographic area variations in prescription drug use. J Pediatr. 2014;134:563–570. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-4250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomsen J, Tos M. Spontaneous improvement of secretory otitis. A long-term study. Acta Oto-Laryngologica. 1981;92:493–499. doi: 10.3109/00016488109133288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lieberthal AS, Carroll AE, Chonmaitree T, Ganiats TG, Hoberman A, Jackson MA, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. J Pediatr. 2013;131:e964–999. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenfeld RM, Schwartz SR, Pynnonen MA, Tunkel DE, Schwartz SR. Clinical practice guideline: Tympanostomy tubes in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;149:S1–35. doi: 10.1177/0194599813487302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daniel M, Kamani T, El-Shunnar S, Jaberoo MC, Harrison A, Yalamachili S, et al. National Institute for Clinical Excellence guidelines on the surgical management of otitis media with effusion: are they being followed and have they changed practice? Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;77:54–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2012.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paradise JL, Dollaghan CA, Campbell TF, Feldman HM, Bernard BS, Colborn DK, et al. Otitis media and tympanostomy tube insertion during the first three years of life: developmental outcomes at the age of four years. J Pediatr. 2003;112:265–277. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.2.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teele DW, Klein JO, Rosner B. Epidemiology of otitis media during the first seven years of life in children in greater Boston: a prospective, cohort study. J Infect Dis. 1989;160:83–94. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Browning G, Rovers M, Williamson I, Lous J, Burton M. Grommets (ventilation tubes) for hearing loss associated with otitis media with effusion in children. Cocharane Collaboration. 2010 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001801.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Glover JA. The Incidence of Tonsillectomy in School Children. Proc R Soc Med. 1938;31:95–112. doi: 10.1177/003591573803101027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wennberg J. Tracking Medicine: A Researcher’s Quest to Understand Health Care. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mulley AG, Trimble C, Elwyn G. Stop the silent misdiagnosis: patients’ preferences matter. BMJ. 2012;345:e6572. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e6572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Infante-Rivard C, Fernandez A. Otitis media in children: frequency, risk factors, and research avenues. Epidemiol Rev. 1993;15:444–465. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Office for National Statistics. Expenditure for Healthcare in the UK: 2011 [Internet] Office for National Statistics; 2013. May 8, [cited 2015 31 July. Available from: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/psa/expenditure-on-healthcare-in-the-uk/2011/art-expenditure-on-healthcare-in-the-uk-2011.html. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith DF, Boss EF. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in the prevalence and treatment of otitis media in children in the United States. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:2306–2312. doi: 10.1002/lary.21090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wallace IF, Berkman ND, Lohr KN, Harrison MF, Kimple AJ, Steiner MJ. Surgical treatments for otitis media with effusion: a systematic review. J Pediatr. 2014;133:296–311. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The Annie E. Casey Foundation. Kids Count Data Center [Internet] The Annie E. Casey Foundation; 2016. [cited 2015 June 24] Available from: http://www.datacenter.kidscount.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 34.NHS Information Centre. Procedure D15.1 Myringotomy with insertion of ventilation tube through tympanic membrane [Internet] The Health and Social Care Information Centre; [Accessed May 31, 2016]. Main procedures and interventions: Hospital Episode Statistics for England. Inpatient statistics, 2010–11. Available from: www.hesonline.nhs.uk. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bauchner H. Shared decision making in pediatrics. Arch Dis Child. 2001;84:246. doi: 10.1136/adc.84.3.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berman S. Otitis media, shared decision making, and enhancing value in pediatric practice. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:186–188. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elwyn G, Laitner S, Coulter A, Walker E, Watson P, Thomson R. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS. BMJ. 2010;341:c5146. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fiks AG, Localio AR, Alessandrini EA, Asch DA, Guevara JP. Shared decision-making in pediatrics: a national perspective. J Pediatr. 2010;126:306–314. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Merenstein D, Diener-West M, Krist A, Pinneger M, Cooper LA. An assessment of the shared-decision model in parents of children with acute otitis media. J Pediatr. 2005;116:1267–1275. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]