Abstract

Objectives

To determine if 6 versus 3 cycles of adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy with or without taxane impacts survival in early stage ovarian clear cell carcinoma (OCCC).

Methods

We retrospectively identified all cases of stage I and II OCCC treated at 5 institutions from January 1994 through December 2011. Patients were divided into 2 groups: those who received 3 versus 6 cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy. Our cohort consisted of 210 patients with stage IA-II disease, 116 of whom underwent full surgical staging. Cox proportional hazards regression and Kaplan-Meier analyses were performed to evaluate progression-free (PFS) and overall survival (OS) between groups.

Results

Among 210 eligible patients, the median age was 53 years (range 30–88). The majority of patients were Caucasian (83.8%). All patients received adjuvant chemotherapy with 90% receiving carboplatin and paclitaxel. Thirty-eight (18.1%) patients received 3 cycles, and 172 (81.9%) patients received 6 cycles of adjuvant treatment. Recurrence rate was comparable between groups (18.4% vs. 27.3% for 3 vs. 6 cycles, p=0.4). There was no impact of 3 versus 6 cycles of chemotherapy on PFS (hazard ratio [HR] 1.4; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.63–3.12, p=0.4) or OS (HR 1.65; 95% CI 0.59–4.65, p=0.3) on univariate analysis. There was no benefit to more chemotherapy in stratified analysis by stage nor on multivariate analysis adjusting for the impact of stage. Subgroup analysis of surgically staged patients also showed no difference in survival between 3 versus 6 cycles of chemotherapy.

Conclusions

Three cycles of platinum with or without taxane adjuvant chemotherapy were comparable to 6 cycles with respect to recurrence and survival in patients diagnosed with early stage ovarian clear cell carcinoma in this retrospective multi-institutional cohort.

Introduction

Ovarian clear cell carcinomas (OCCC) comprise approximately 5–25% of all ovarian cancers [1–5] and have been noted to have distinctly different clinical behavior from the more common papillary serous subtype. OCCC often presents as a singular, large, unilateral mass; is more frequently associated with endometriosis; presents at an early stage and with an increased risk of thromboembolic events [1–3, 6]. Prognosis in advanced stages is poor [7], but in early-stage disease, prognosis may be better when compared to high-grade serous carcinomas, particularly in those arising from endometriosis and with less than stage IC disease [8–10]. In a large retrospective multivariate analysis of stage I invasive epithelial ovarian cancer, OCCC did not have a poorer prognosis compared to the papillary serous subtype [11].

The adjuvant treatment for early stage epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) has been studied in a series of phase III randomized clinical trials. Low-risk groups that do not require adjuvant chemotherapy (stage IA and IB, grade 1 cancer) were defined by the GOG 7601 trial [12]. In contrast, other patients with early-stage EOC (stage IA or IB and unfavorable histology including grade 3 or clear cell, stage IC, or stage II) are candidates for adjuvant treatment based upon 5-year recurrence rates of approximately 25– 45% [13, 14].

The GOG 157 trial compared three versus six cycles of adjuvant paclitaxel and carboplatin chemotherapy in patients with high-risk, early-stage ovarian cancer [13]. The recurrence risk was 24% lower with six versus three cycles of chemotherapy, but this was not statistically significant (HR 0.76, CI 0.51 – 1.13), and the authors concluded that the three additional cycles of chemotherapy added toxicity without significantly reducing the risk of cancer recurrence. A later post-hoc analysis of this trial suggested that the subset of patients with high-grade serous histology benefit from six cycles of chemotherapy (recurrence-free (RFS) survival HR 0.33, 95% CI 0.14–0.77), but that OCCC histology does not (RFS HR 0.90, 95% CI 0.43, 1.91). Patients with OCCC represented about 30% (n=130) of the GOG 157 patient population [13, 15]. We sought to evaluate the impact of three versus six cycles of adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy in early-stage OCCC via a multi-institutional retrospective cohort.

Methods

With institutional review board approval, we collected cases of FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) stage I and II OCCC between January 1994 and December 2011 from 5 institutions including Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, The University of Oklahoma, University of Alabama at Birmingham and University of California Los Angeles. Medical records were reviewed and data were abstracted including patient demographics, FIGO stage, operative staging procedures, adjuvant therapies, and follow-up including recurrence and death events. Patients were included if they received either 3 or 6 cycles of platinum based regimen with or without taxane chemotherapy. Patients were excluded if they did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy or received a number or cycles of chemotherapy other than 3 or 6 cycles. Gynecologic pathologists at independent tumor boards reviewed all cases as part of clinical decision-making.

The primary outcomes were progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). Descriptive statistics, Cox proportional hazards regression model, Kaplan-Meier estimation, log-rank test, Mann-Whitney U test, and χ2 test were used for statistical analyses. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Two hundred fifty-nine patients with FIGO stage I and II OCCC were identified. Among these, 210 received either 3 or 6 cycles of platinum with or without taxane adjuvant chemotherapy and were included in the analysis. The majority of patients received adjuvant carboplatin and paclitaxel (n=189, 90%). Only 2 (1%) patients received cisplatin and paclitaxel. Three (2%) patients received single agent carboplatin. Furthermore, 15 (7%) received alternative platinum-based chemotherapy regimens including neoadjuvant carboplatin and paclitaxel, intraperitoneal chemotherapy, and carboplatin and gemcitabine. No patients refused or died prior to adjuvant chemotherapy.

Patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. Thirty-eight women (18%) received 3 cycles and 172 (82%) received 6 cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy. Between patients who received 3 versus 6 cycles of chemotherapy, there were no differences in race or stage. The stage distribution for the entire cohort included 29% stage IA, 1% stage IB, 47% stage IC and 22% stage II. Patients who received 6 cycles of chemotherapy were significantly younger (50.9 versus 57.5 years, p=0.03) and more frequently had pure OCCC histology (97% versus 84%, p=0.02). Full surgical staging was defined as hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy. A higher proportion of patients receiving 3 cycles of chemotherapy underwent full staging compared to those receiving 6 cycles (71% vs. 52%, p=0.03). Forty-one patients underwent a fertility sparing surgery including cystectomy or unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy without hysterectomy. Fertility sparing was comparable between 3 versus 6 cycles (20% vs. 19%, p=0.9).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of patients with early-stage OCCC who underwent either 3 or 6 cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy (n=210)

| Treatment

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Carboplatin ± Paclitaxel × 3 |

Carboplatin ± Paclitaxel × 6 |

||

|

|

|||

| Characteristics | n=38 | n=172 | P-value |

| Median age, years (range) | 57.5 (31–82) | 50.9 (30–88) | 0.03* |

| Race (n, %) | 0.72¥ | ||

| Caucasian | 32 (84) | 144 (81.8) | |

| African American | 1 (2.5) | 6 (3.5) | |

| Asian | 4 (11) | 12 (7.4) | |

| Hispanic | 0 (0) | 4 (1.6) | |

| Other | 1 (2.5) | 6 (3.3) | |

| Stage (n, %) | 0.8¥ | ||

| IA | 11 (29) | 51 (30) | |

| IB | 0 (0) | 3 (2) | |

| IC | 19 (50) | 79 (46) | |

| IC1 | 10 (26) | 71 (41) | |

| IC2 | 6 (16) | 2 (1) | |

| IC3 | 3 (8) | 6 (3) | |

| II | 8 (21) | 39 (23) | |

| Histologic type (n, %) | 0.02¥ | ||

| Clear cell | 32 (84) | 164 (97) | |

| Mixed clear cell and serous | 2 (5) | 5 (3) | |

| Mixed clear cell and non-serous | 4 (11) | 3 (2) | |

| Full staging (n, %) | 27 (71) | 89 (52) | 0.03¥ |

| Pelvic lymphadenectomy | 35 (92) | 136 (79) | 0.06¥ |

| Para-aortic lymphadenectomy | 36 (95) | 121 (70) | 0.002¥ |

| Hysterectomy | 30 (79) | 139 (80) | 0.9¥ |

| Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy | 30 (79) | 139 (80) | 0.9¥ |

| Omentectomy | 30 (79) | 141 (82) | 0.3¥ |

| Median # pelvic lymph nodes (range) | 10 (0–27) | 8 (0–45) | 0.08* |

| Median # para-aortic lymph nodes (range) | 4 (0–10) | 3 (0–29) | 0.5* |

| Cystectomy only | 1 (3) | 4 (2) | 0.9¥ |

Mann-Whitney U test

Χ2 test

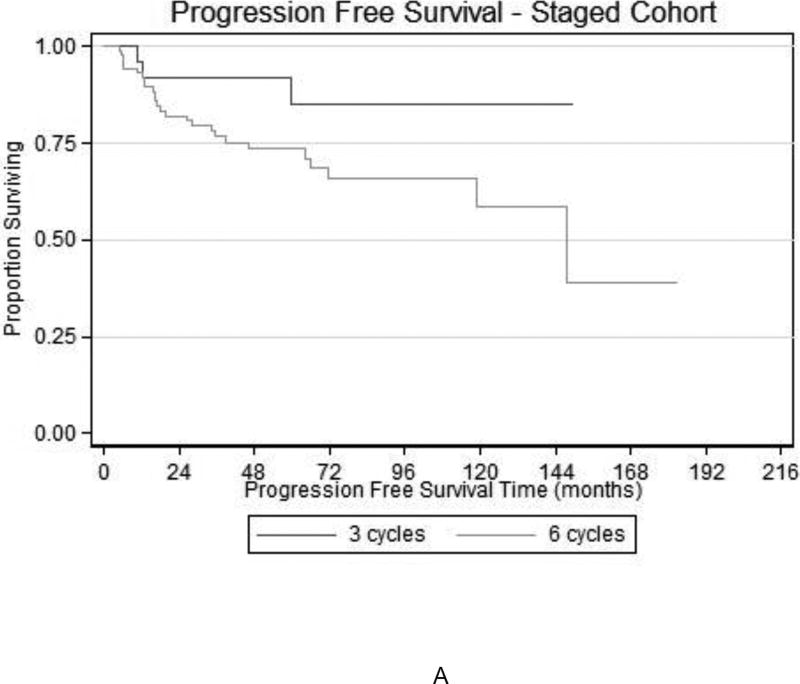

Among the 210 patients who received either 3 or 6 cycles of chemotherapy, there were 54 recurrences and 40 deaths. In the entire cohort, the number of chemotherapy cycles (3 vs. 6) did not influence PFS (HR 1.41; 95% CI 0.85–3.12, p=0.4) or OS (HR 1.65; 95% CI 0.58–4.65, p=0.3. Figure 1 demonstrates the survival curves for PFS and OS among all early stage patients. Those who received 6 cycles appeared to have a trend towards worse survival, although notably, many of these women had stage IC disease. To account for the prognostic impact of stage, we performed subset analyses and compared survival outcomes across specific sub-stages. When comparing stage IC patients (n=98), there was no difference in either PFS (HR 1.34, 95% CI 0.46–3.90, p=0.6) or OS (HR 3.67, 95% CI 0.48–27.8, p=0.2) with 3 versus 6 cycles of chemotherapy. Figure 2 demonstrates the survival curves for PFS and OS among the stage IC cohort. Comparisons of PFS and OS in stage II (n=47) patients who received 3 versus 6 cycles were also not significant (PFS HR 0.87, 95% CI 0.25–3.01, p=0.8; OS HR 0.61, 95% CI 0.17–2.24, p=0.4). There were not enough events to compare outcomes in the stage IA or IB subset.

FIGURE 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimation of (A) PFS and (B) OS among patients with stage I-II OCCC who completed 3 or 6 cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy (n=210; p=0.9 and p=0.3, respectively)

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimation of (A) PFS and (B) OS among patients with stage IC OCCC who completed 3 or 6 cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy (n=98; p=0.6 and p=0.2, respectively)

In univariate analysis for variables influencing PFS, only stage (IA/IB vs. IC vs. II) was a significant factor (HR 1.81, 95% CI 1.25–2.63, p=0.02). Age, BMI and race (Asian versus non-Asian) were not significant. On multivariate analysis adjusting for stage, number of chemotherapy cycles (3 vs. 6) remained non-significant (HR 1.41, 95% CI 0.63–3.11, p=0.4).

In univariate analysis for variables influencing OS, stage (IA/IB vs. IC vs. II) was again the only significant factor (HR 1.84, 95% CI 1.21–2.83, p=0.005). Age, BMI and race (Asian vs. non-Asian) were not significant. On multivariate analysis adjusting for stage, number of chemotherapy cycles (3 vs. 6) remained non-significant (HR 1.70, 95% CI 0.61–4.80, p=0.3).

A subgroup analysis was performed on the cohort that underwent full surgical staging. When comparing 3 versus 6 cycles for all stages, PFS and OS were similar (HR 1.42, 95% CI 0.95–2.12, p=0.08 and HR 1.27, 95% CI 0.85–1.90, p=0.25, respectively). Figure 3 demonstrates the survival curves for PFS and OS for 3 versus 6 cycles of chemotherapy in the fully surgically staged cohort. When evaluating by stage, including IA, IC, and II, no differences in PFS or OS were observed (data not shown) for 3 vs. 6 cycles of chemotherapy.

FIGURE 3.

Kaplan-Meier estimation of (A) PFS and (B) OS among patients with fully-staged early stage OCCC who completed 3 or 6 cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy

A comparison of 5-year recurrence free survival (RFS) and OS between a subgroup analyses of GOG 157 evaluating non-serous histology and this study is shown in Figure 4. Outcomes between groups appear similar. An analysis combining the values from both studies were excluded given the GOG 157 analysis included other non-serous histology.

Discussion

In this multi-institutional retrospective cohort of patients with early-stage OCCC, we found similar outcomes between patients receiving 3 versus 6 cycles of adjuvant platinum plus or minus taxane chemotherapy. To date, the impact of adjuvant chemotherapy in early-stage OCCC has not been fully evaluated due to lack of large-scale studies. ICON1, EORTC-ACTION and GOG 157 evaluated the impact of adjuvant chemotherapy on all histologic subtypes of early stage ovarian cancer [13, 16, 17]. GOG 157 found no statistical difference in survival with 3 versus 6 cycles of chemotherapy, but there appeared to be a trend toward reduced recurrence risk when patients received 6 cycles at the trade-off of increased treatment-related toxicity [13]. All of these trials were limited in their ability to make firm conclusions for rare histologies, but a post-hoc analysis of GOG 157 suggested that 3 cycles of chemotherapy are sufficient to treat early stage OCCC [15]. The phase III Japanese JGOG3107/GCIG trial evaluating irinotecan-cisplatin compared to paclitaxel-carboplatin in stage I-IV OCCC found no difference in survival [18]. Our retrospective multi-institutional cohort study adds to the literature that suggests that number of chemotherapy cycles may not impact survival in this rare histologic subtype and that the optimal treatment regimen has yet to be identified.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends platinum and taxane adjuvant chemotherapy for stage IA or IB with grade 3 or high-grade histology and stage IC, all grades [19]. While the benefit for 3 or 6 cycles is unclear in early-stage disease, many providers opt to proceed with 6 cycles due to the inherent aggressive nature of OCCC. Some studies have suggested the comparative poor prognosis of OCCC when compared to its histologic counterparts when matched stage for stage [5, 7]. Further, OCCC appears to be associated with chemoresistance, especially in Asian patients [20]. Thus, the question of whether or not there is an added benefit with more cycles of chemotherapy in this relatively chemoresistant histology is an ongoing clinical question.

Our data suggests that 3 cycles compared to 6 cycles of platinum and taxane-based chemotherapy for stage I and II OCCC patients does not significantly influence recurrence rates or survival. Paradoxically, we observed a trend towards worse outcomes in patients receiving 6 versus 3 cycles of chemotherapy. This suggests a potential selection bias in clinical practice, with patients with worse prognostic features being selected to receive more aggressive therapy. We found advancing stage (from IA/IB to IC to II) to be associated with worse PFS and OS outcomes. We accounted for the impact of stage through a stratified analysis by stage as well as through a multivariate analysis. We also accounted for the effect of full surgical staging including pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy on outcomes via a subgroup analysis. When accounting for the potential confounding impact of stage on survival, we still did not observe an advantage to 6 over 3 cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy.

This is the largest study to our knowledge comparing 3 versus 6 cycles of chemotherapy in early stage OCCC patients. Our study has limitations with the most recognizable being its retrospective nature. Our study suggests a trend towards better outcomes in patients receiving 3 cycles of chemotherapy and likely reflects physician bias towards selecting 3 versus 6 cycles of adjuvant therapy for individual patients based on varying clinical factors. Further, our study is underpowered to effectively answer the question regarding the non-inferiority of 3 versus 6 cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy. If we were to design a prospective trial to address this question with an alpha of 0.05 and 80% power, we would need to recruit over 4000 patients to find a difference in hazard ratio of 10% between arms. Such a trial is unlikely to be feasible in this rare histologic subtype of ovarian cancer. Nevertheless, we feel our study provides an important contribution as we found no separation in survival curves to favor the administration of more chemotherapy.

In conclusion, early-stage OCCC in patients undergoing surgery followed by adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy had similar recurrence and survival outcomes when given 3 versus 6 cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy in this multi-institutional retrospective cohort study, although this study is underpowered to effectively answer this question. Further clinical trials, including the use of novel agents, are needed to better illuminate the best strategy for treating early stage OCCC.

TABLE 2.

Multivariate analysis of factors influencing PFS among patients with early-stage OCCC who completed 3 or 6 cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy

| Tumor Characteristic | HR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage (IA/IB vs. IC vs. II) | 1.81 | 1.24–2.62 | 0.002 |

| 3 versus 6 cycles | 1.40 | 0.63–3.11 | 0.4 |

Cox proportional hazards regression model

TABLE 3.

Multivariate analysis of factors influencing OS among patients with early-stage OCCC who completed 3 or 6 cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy

| Tumor Characteristic | HR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage (IA/IB vs. IC vs. II) | 1.85 | 1.21–2.82 | 0.004 |

| 3 versus 6 cycles | 1.70 | 0.60–4.80 | 0.3 |

Cox proportional hazards regression model

TABLE 4.

Comparison of 5-year RFS and OS to subgroup analysis of GOG 157 evaluating fully staged non-serous cancers

| Study | 5-yr RFS (%) | p-value | 5-yr OS (%) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| 3 cycles | 6 cycles | 3 cycles | 6 cycles | |||

|

|

|

|||||

| Chan et al. (2010) | 78.6 | 78.7 | 0.8 | 84.1 | 83.0 | 0.8 |

| Prendergast et al. (2016) | 80.0 | 66.7 | 0.7 | 87.5 | 90.9 | 0.7 |

Cox proportional hazards regression model

Highlights.

Stage I-II OCCC survival similar after 3 or 6 cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy

Patients with early stage I and II OCCC may be candidates for a 3 cycle approach

Optimal chemotherapy choice and duration for OCCC requires further study

Acknowledgments

Drs. Leitao and Mueller are funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented as a Poster Presentation at the 45th Annual Meeting of the Western Association of Gynecologic Oncologists

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Aure JC, Hoeg K, Kolstad P. Mesonephroid tumors of the ovary. Clinical and histopathologic studies. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1971;37:860–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kennedy AW, Biscotti CV, Hart WR, Webster KD. Ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma. Gynecologic oncology. 1989;32:342–9. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(89)90637-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crozier MA, Copeland LJ, Silva EG, Gershenson DM, Stringer CA. Clear cell carcinoma of the ovary: a study of 59 cases. Gynecologic oncology. 1989;35:199–203. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(89)90043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Omura GA, Brady MF, Homesley HD, Yordan E, Major FJ, Buchsbaum HJ, et al. Long-term follow-up and prognostic factor analysis in advanced ovarian carcinoma: the Gynecologic Oncology Group experience. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1991;9:1138–50. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.7.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O'Brien ME, Schofield JB, Tan S, Fryatt I, Fisher C, Wiltshaw E. Clear cell epithelial ovarian cancer (mesonephroid): bad prognosis only in early stages. Gynecologic oncology. 1993;49:250–4. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1993.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kobayashi H, Sumimoto K, Kitanaka T, Yamada Y, Sado T, Sakata M, et al. Ovarian endometrioma--risks factors of ovarian cancer development. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology. 2008;138:187–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goff BA, de la Cuesta RS, Muntz HG, Fleischhacker D, Ek M, Rice LW, et al. Clear cell carcinoma of the ovary: a distinct histologic type with poor prognosis and resistance to platinum-based chemotherapy in stage III disease. Gynecologic oncology. 1996;60:412–7. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1996.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamashita Y. Ovarian cancer: new developments in clear cell carcinoma and hopes for targeted therapy. Japanese journal of clinical oncology. 2015;45:405–7. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyu221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kobel M, Kalloger SE, Santos JL, Huntsman DG, Gilks CB, Swenerton KD. Tumor type and substage predict survival in stage I and II ovarian carcinoma: insights and implications. Gynecologic oncology. 2010;116:50–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anglesio MS, Carey MS, Kobel M, Mackay H, Huntsman DG. Clear cell carcinoma of the ovary: a report from the first Ovarian Clear Cell Symposium, June 24th, 2010. Gynecologic oncology. 2011;121:407–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vergote I, De Brabanter J, Fyles A, Bertelsen K, Einhorn N, Sevelda P, et al. Prognostic importance of degree of differentiation and cyst rupture in stage I invasive epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Lancet (London, England) 2001;357:176–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03590-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young RC, Walton LA, Ellenberg SS, Homesley HD, Wilbanks GD, Decker DG, et al. Adjuvant therapy in stage I and stage II epithelial ovarian cancer. Results of two prospective randomized trials. The New England journal of medicine. 1990;322:1021–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199004123221501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bell J, Brady MF, Young RC, Lage J, Walker JL, Look KY, et al. Randomized phase III trial of three versus six cycles of adjuvant carboplatin and paclitaxel in early stage epithelial ovarian carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecologic oncology. 2006;102:432–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmed FY, Wiltshaw E, A'Hern RP, Nicol B, Shepherd J, Blake P, et al. Natural history and prognosis of untreated stage I epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1996;14:2968–75. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.11.2968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan JK, Tian C, Fleming GF, Monk BJ, Herzog TJ, Kapp DS, et al. The potential benefit of 6 vs. 3 cycles of chemotherapy in subsets of women with early-stage high-risk epithelial ovarian cancer: an exploratory analysis of a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;116:301–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.10.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trimbos JB, Vergote I, Bolis G, Vermorken JB, Mangioni C, Madronal C, et al. Impact of adjuvant chemotherapy and surgical staging in early-stage ovarian carcinoma: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer-Adjuvant ChemoTherapy in Ovarian Neoplasm trial. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2003;95:113–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colombo N, Guthrie D, Chiari S, Parmar M, Qian W, Swart AM, et al. International Collaborative Ovarian Neoplasm trial 1: a randomized trial of adjuvant chemotherapy in women with early-stage ovarian cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2003;95:125–32. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.2.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sugiyama T, Okamoto A, Enomoto T, Hamano T, Aotani E, Terao Y, et al. Randomized Phase III Trial of Irinotecan Plus Cisplatin Compared With Paclitaxel Plus Carboplatin As First-Line Chemotherapy for Ovarian Clear Cell Carcinoma: JGOG3017/GCIG Trial. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34:2881–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.66.9010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Network NCC. Ovarian Cancer Including Fallopian Tube Cancer and Primary Peritoneal Cancer (Version 1.2016) 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sugiyama T, Kamura T, Kigawa J, Terakawa N, Kikuchi Y, Kita T, et al. Clinical characteristics of clear cell carcinoma of the ovary. Cancer. 2000;88:2584–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]