Abstract

Research suggests that the discriminative and affective aspects of touch are processed differently in the brain. Primary somatosensory cortex is strongly implicated in touch discrimination, whereas insular and prefronal regions have been associated with pleasantness aspects of touch. However, the role of secondary somatosensory cortex (S2) is less clear. In the current study we used inhibitory repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) to temporarily deactivate S2 and probe its role in touch perception. Nineteen healthy adults received two sessions of 1-Hz rTMS on separate days, one targeting right S2 and the other targeting the vertex (control). Before and after rTMS, subjects rated the intensity and pleasantness of slow and fast gentle brushing of the hand and performed a 2-point tactile discrimination task, followed by fMRI during additional brushing. rTMS to S2 (but not vertex) decreased intensity ratings of fast brushing, without altering touch pleasantness or spatial discrimination. MRI showed a reduced response to brushing in S2 (but not in S1 or insula) after S2 rTMS. Together, our results show that reducing touch-evoked activity in S2 decreases perceived touch intensity, suggesting a causal role of S2 in touch intensity perception.

Keywords: tactile, touch, intensity, pleasantness, rTMS, secondary somatosensory cortex

Introduction

Evidence suggests that discriminative aspects of touch (what, where, when) involve different neural processing than touch affect (pleasantness or unpleasantness). Primary (e.g. [8, 18, 25, 34]) and secondary (e.g. [11, 22]) somatosensory cortices are most commonly associated with tactile discrimination, whereas touch pleasantness correlates with neural responses in other brain regions, including orbital frontal cortex (OFC) [13], posterior insula (pINS; [24]), superior temporal sulcus [19], and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC; [10]).

A recent meta-analysis of fMRI studies showed that S1 is activated mainly by discriminative touch and pINS mainly by affective touch paradigms [25]. Evidence related to S2, on the other hand, showed a high likelihood of response to discriminative as well as affective aspects of touch. It is not clear to what extent the S2 activation reflects discriminatory touch processing correlated with affective touch (such as discrimination of soft textures, or attention directed towards pleasing stimuli), or if S2 is directly involved in the perception of touch pleasantness [25].

Using single pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to disrupt cortical activity, investigators found that stimulation of contralateral S2, but not S1, reduced laser-evoked pain on the left hand [25], suggesting that S2 is more important than S1 in pain intensity perception. However, the causal role of S2 in non-nociceptive touch perception has not been tested. Low frequency repetitive TMS (rTMS) is used to produce inhibition of its cortical target [5, 21, 23], allowing a causal test of the target’s function. We recently reported that rTMS inhibition of right hemisphere S1 decreased tactile spatial discrimination and increased perceived touch intensity for the contralateral hand, but had no effect on touch pleasantness [12]. Since we observed that intensity ratings were positively correlated with fMRI BOLD response in contralateral S1 and insular cortex and bilateral S2 [4] in a separate fMRI session of the same study, it seemed unlikely that the increase in intensity was a direct result of S1 inhibition. We therefore speculated that the effect of S1 rTMS on touch intensity occurred due to a disinhibition of S2 as a consequence of the S1 inhibition.

The current study uses inhibitory rTMS to reduce S2 activation and thus test its causal role in touch intensity, pleasantness, and spatial discrimination. We hypothesized that rTMS deactivation of S2 would decrease perceived touch intensity and possibly also affect touch pleasantness, but not alter spatial discrimination.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Nineteen healthy, right-handed adults (mean age 29.5 ± 7.5 years; range 18–45 years; 8 male) completed both rTMS sensory testing sessions; seventeen of these completed both fMRI scans.

Exclusion criteria included major medical or psychological conditions, chronic pain, substance or alcohol dependence or abuse, dermatological abnormalities relevant to somatosensation, pregnancy and MRI and TMS safety exclusion criteria [4]. Subjects were also screened for adequate sensory acuity on the left palm, defined by above-chance performance on the two-point discrimination task (2PD). All participants provided informed consent and were monetarily compensated in accordance with approval from the NIH CNS Institutional Review Board.

Experimental design

Each subject received two rTMS sessions: one targeting the right hemisphere S2 and the other targeting the vertex. Session order was counterbalanced across participants. Subjects performed sensory testing before and after each rTMS session, blinded to hypotheses and tester blind to rTMS location (see [4] for details). After rTMS, participants completed a brief fMRI brushing task and anatomical scan.

Stimulation parameters

We conducted 20-min of 1-Hz rTMS to S2 or vertex using an H8 deep TMS H-coil [26, 39] to achieve deeper penetration than that produced by Figure-8 coils. At 120% of resting motor threshold (RMT), it is expected to produce 100V/m up to 3.5 cm from the scalp (personal communication, Abraham Zangen and Yiftach Roth, October 2016), a field strength sufficient to induce an evoked potential in motor cortex with a single pulse [27, 29, 35]. Affecting neural activity 3.5cm from the scalp is deep enough to include the entire parietal operculum, but falls short of the insula. The H-coil was driven by a Super Rapid 2 Transcranial Magnetic Stimulator (Magstim, Whitland, UK). rTMS sessions were separated by at least 24 hours and were spaced at least one week apart from any TMS session in other studies. During rTMS participants wore earplugs and watched a silent movie of landscapes.

S2: During the S2 session, stimulation was performed at 110% of H-coil RMT. Figure-8 RMT was obtained at the beginning of each rTMS session, using techniques described previously [4]. Based on calculated coil equivalencies, we then estimated the H-coil RMT by adding 10%. Four subjects received less intense stimulation (81–97% H-coil RMT) due to stimulation-related pain or discomfort on the scalp.

Vertex: Vertex stimulation was used to produce scalp sensations without affecting neural tissue. Vertex stimulation with Figure-8 coils has no demonstrable effect on somatosensory discriminative performance (see [4]). To produce a magnetic field with the H-coil that would reach the scalp without stimulating the underlying cortex, we inserted a 4-cm thick foam spacer between the coil and the scalp and stimulated at 100% of the Magstim output [4].

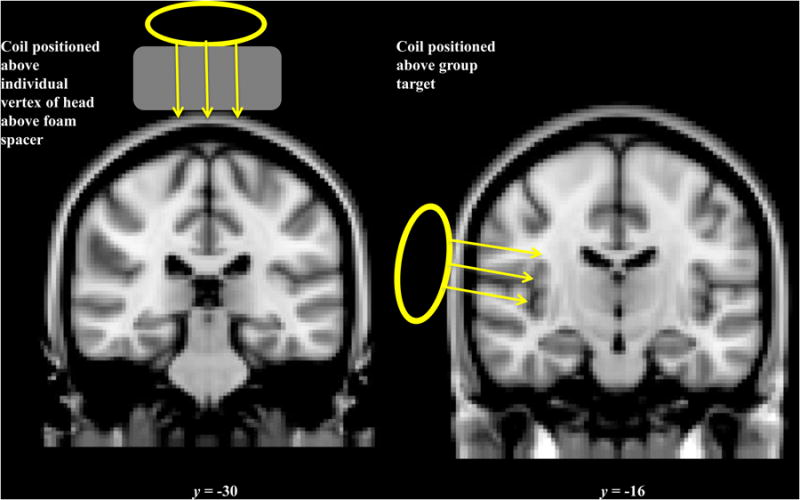

rTMS target localization

The motor target for conducting RMT and the S2 and vertex targets were determined for each subject using previously described methods and previously obtained functional and anatomical MRI scans [4]. The S2 target was the voxel in pINS just medial to S2 that showed the largest group-level response to slow brushing on the back of the hand in our previous study (x = 38, y = −16, z = 12 in MNI standard space;[4]). S2 lies in the parietal operculum superficial to pINS; by targeting pINS and placing the H- coil tangential to the scalp surface, we aimed to stimulate along the full parietal operculum (Figure 1). The vertex target was placed manually above the interhemispheric fissure in the same coronal plane as the peak S1 response to hand brushing. Both the vertex and S2 targets were drawn on a fabric electro-cap with no electrodes attached (Electro-Cap International, Inc., OH, USA) while tracking the subject’s head position using the Brainsight TMS Navigation system (Brainsight, Rogue Research, Montreal, Canada). Participants were then relocated to the MRI center where the target drawn on the cap was used to center the H-coil.

Figure 1.

Placement of the TMS coil over vertex (top) and S2 (bottom).

Sensory Testing

Participants completed a brushing task and a two-point discrimination (2PD) task on the left hand before and after rTMS, with task order counterbalanced across participants. Baseline sensory testing (8–10 min) was conducted 20–30 minutes before rTMS and ~3 minutes after the final rTMS pulse. Task completion occurred 9–14 minutes after the final rTMS pulse, remaining within the lower temporal durations reported for rTMS-induced inhibition [4]. In the vertex condition, due to technical difficulties, two participants completed sensory testing later (22 and 30 min post-rTMS, respectively). Mood and anxiety ratings were collected verbally at the beginning of sensory testing (good mood, bad mood, anxiety, and calmness scales anchored with 0 = neutral and 10 = extremely good/bad/anxious/calm). Ratings of maximum TMS-related scalp pain were collected directly after rTMS on a 0–100 visual analog scale (VAS).

Brushing task

Using techniques described previously [4], the palm and back of participant’s left hand were stroked at slow (3 cm/sec) and fast (30 cm/sec) speeds during separate 6-sec blocks. Fast brushing is rated as more intense than slow brushing (e.g. [18]), while slow brushing is rated as more pleasant and is the optimal stimulus for C-tactile (CT) afferent fibers linked to pleasantness perception in hairy skin [4]. The four types of brushing were chosen to create variability in the intensity and pleasantness of the stimuli by activating different proportions of Aβ and CT fibers. Participants rated each type of brushing on VAS scales for intensity and pleasantness (see [4]).

Two-point discrimination task (2PD)

Using procedures previously described [4], participants were touched on the left thenar eminence using an aesthesiometer and indicated whether they perceived one or two plastic tips.

fMRI

The MRI session included a functional scan of hand brushing, using imaging parameters previously described [4]. Participants provided VAS ratings of intensity and pleasantness of two blocks of brushing, each containing ten 6-sec trials of slow brushing on the back of the left hand (3 cm/sec). The two ratings, on average, were made 26 and 30 minutes after the last rTMS pulse.

Data Analysis

Task fMRI analysis

Preprocessing

fMRI preprocessing was identical to that performed in [4] except that alignment of the functional scan to the structural scan was conducted using a 6 parameter rigid-body transformation for four participants when boundary-based registration failed.

Mass Univariate GLM Analysis

First-level analysis was conducted in FEAT (FMRI Expert Analysis Tool; part of FSL) as described in [4].

Group-level Analysis

A repeated measures three level analysis was conducted using sequential fixed and mixed effects models using FSL’s FLAME (FMRIB’s local analysis of mixed effects; [4]). This analysis combined the fMRI scans from both rTMS sessions to identify brain regions with a significant response to brushing > rest at the group-level. The analysis was thresholded at Z = 3 and Gaussian Random Field (GRF) theory was applied to identify clusters of voxels significant at the p < 0.01 level. In addition, to compare the effects of rTMS between sessions, three group level analyses were performed using mixed effects FLAME models to identify regions with a significant BOLD response to brushing 1) after vertex rTMS, 2) after S2 rTMS, and 3) with greater BOLD response to brushing after the vertex rTMS than after S2 rTMS. The analysis was thresholded at Z = 3 and Gaussian Random Field (GRF) theory was applied to identify clusters of voxels significant at the p < 0.01 level. Analysis was repeated p < 0.05 to check for marginal effects between rTMS conditions.

Region of Interest (ROI) Analyses

5 mm spherical ROIs were centered around the peak group-level BOLD response to hand brushing in right primary somatosensory cortex (S1; MNI coordinates 26, −36, 70), right S2 (62, −18, 18), right pINS (36, −18, 22), and left S2 (−58, −22, 16). The highest peak in S2 bordered pINS, so we selected the second highest peak, in superficial S2 proximal to the TMS coil, a location consistent with the hand/arm topography of S2 [28, 33]. An additional 5mm spherical ROI was centered around the rTMS target in pINS (38, −16, 12). Median COPE (contrast of parameter estimates) values were extracted from the ROIs using Featquery (part of FSL).

Student’s t-tests were conducted to compare median COPE values for each ROI between rTMS sessions and to compare average fMRI ratings of pleasantness and intensity between sessions.

Analysis of sensory testing

Intensity and pleasantness ratings

Baseline intensity and pleasantness ratings of fast and slow brushing (averaged across sessions) were compared using paired Student’s t-tests. Intensity change scores (after rTMS – before rTMS) were not normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilk p = 0.003), so nonparametric paired signed-rank Wilcoxon tests were used to compare rating change scores of fast and slow brushing (for intensity and pleasantness separately) between the S2 and vertex sessions.

Two-point discrimination (2PD)

For each distance, 2PD accuracy was calculated using techniques described previously [4].

Results

fMRI Results

S2 rTMS alters S2 BOLD response to brushing

Across both rTMS sessions, the brushing task activated the anticipated brain regions, including contralateral S1, bilateral S2, and contralateral pINS (Table 1; Figure 2).

Table 1.

Activation evoked by brushing on the palm and back of the left hand. Regions responding to brush > rest in both scans. Peak defined as the voxel in the cluster with the highest Z score. Clusters are displayed above a statistical threshold of Z > 3, whole-brain corrected for multiple comparisons (p < 0.01; N = 17). x, y and z MNI coordinates correspond to the left–right, anterior–posterior and inferior–superior axes, respectively.

| Location of cluster peaks | Peak MNI Coordinates (x, y, z) | Peak Z score | # of voxels | Cluster p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R secondary somatosensory cortex (parietal operculum) and posterior insula | 44 | −26 | 20 | 5.09 | 1087 | p < 0.00001 |

| L angular gyrus and lateral occipital cortex | −48 | −52 | 52 | 4.33 | 536 | p < 0.00001 |

| L Cerebellum | −26 | −50 | −24 | 4.34 | 299 | p = 0.00003 |

| L Cerebellum | −44 | −66 | −42 | 3.96 | 227 | p = 0.0003 |

| L Cerebellum | −22 | −58 | −50 | 4.71 | 169 | p = 0.003 |

| L secondary somatosensory cortex (central opercular cortex and parietal operculum) | −58 | −22 | 16 | 4.60 | 162 | p = 0.003 |

| R lateral occipital cortex | 42 | −62 | 52 | 3.82 | 149 | p = 0.005 |

| R primary somatosensory cortex | 26 | −36 | 70 | 4.00 | 144 | p = 0.007 |

| R central opercular cortex | 44 | −6 | 8 | 4.07 | 137 | p = 0.009 |

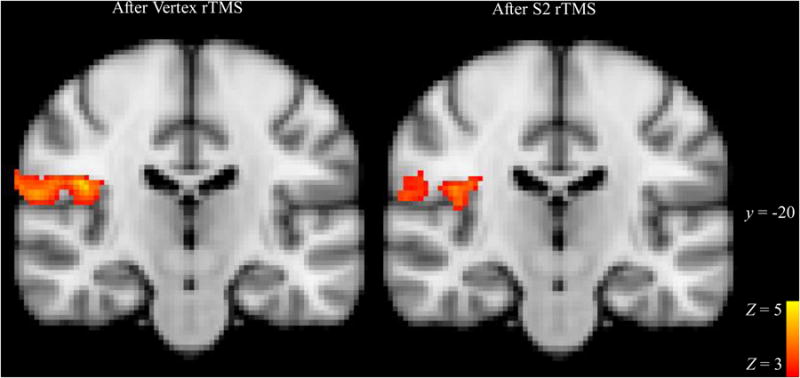

Figure 2.

BOLD response to slow brushing stimulus in S2 after rTMS to S2 or Vertex. Significant clusters of BOLD activations to brushing > rest after Vertex rTMS (control; left panel) and S2 rTMS (right panel) are displayed at a representative slice through S2 cortex, y = 20. Clusters are displayed above a statistical threshold of Z > 3, whole-brain corrected for multiple comparisons (p < 0.001). x and y indicate MNI coordinates. The images are shown in radiological convention.

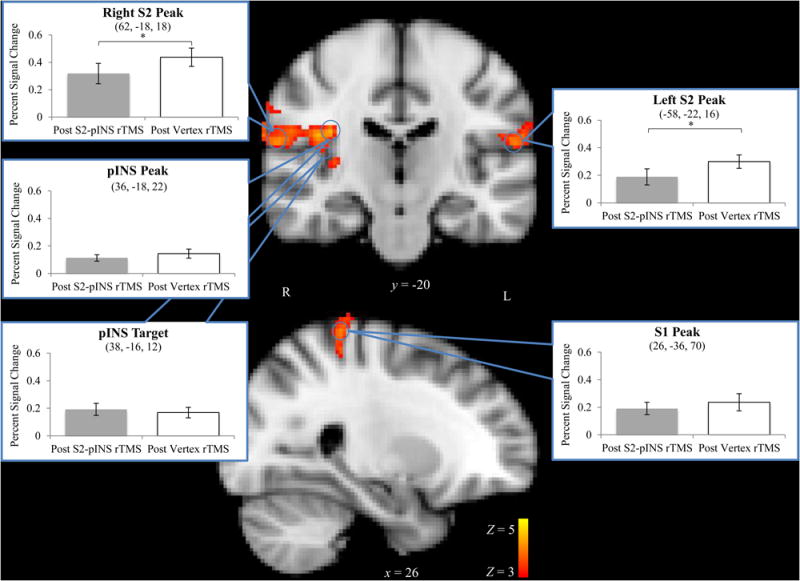

A whole-brain analysis found no significant cluster-corrected differences in brushing-evoked BOLD response after rTMS to S2 versus vertex. However, ROI analysis revealed significantly lower bilateral S2 responses to brushing after S2 rTMS than after vertex rTMS (right S2 M = 0.32, Vertex M = 0.44, t(16) = 1.87, one-tailed p = 0.04; left S2 M = 0.19, Vertex M = 0.30, t(16) = 2.3, p = 0.04) (Figure 3). Reductions in right and left S2 showed a trend towards correlation, r(15) = 0.46, two-tailed p = 0.066. Neither the right pINS peak brushing ROI nor the right pINS rTMS target ROI (peak brushing activation from [4]) differed between rTMS sessions (S2 M = 0.14, Vertex M = 0.11, t(16) = 0.94, p = 0.36 and S2 M = 0.17, Vertex M = 0.19, t(16) = 0.60, p = 0.56, respectively). Right S1 did not differ between rTMS sessions (S2 M = 0.24, Vertex M = 0.19, t(16) = 0.78, p = 0.45) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Brushing-evoked BOLD response averaged across rTMS sessions with ROI analyses superimposed. Clusters are displayed above a statistical threshold of Z > 3, whole-brain corrected for multiple comparisons (p < 0.01). 5 mm spheres were drawn around peak brushing activations (blue circles). Only right and left S2 ROIs showed a significantly different mean BOLD response to brushing after rTMS to S2 (grey bars, left) versus rTMS to the vertex (white bars, right). x and y indicate MNI coordinates. The right side of the images correspond to the left side of the brain, * = one-tailed p < 0.05. Error bars ± SEM.

rTMS Sensory Results

S2 rTMS decreases perceived intensity of fast brushing; no effect on pleasantness perception

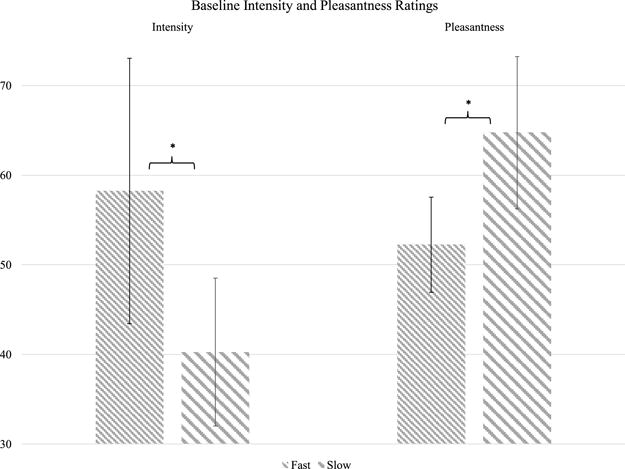

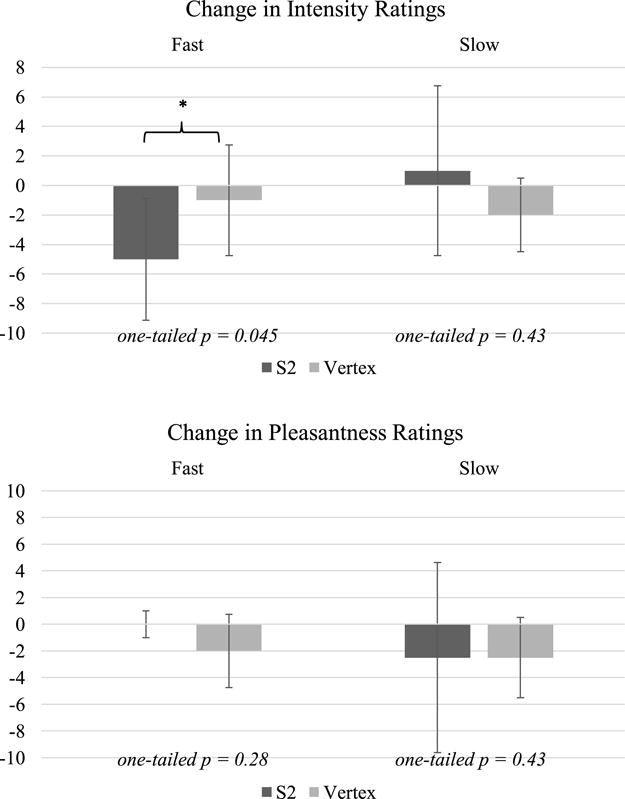

Before rTMS (averaged across hand locations and sessions), participants rated fast brushing as more intense than slow brushing (Wilcoxon signed rank test, Z = −3.38, p < 0.001; Figure 4) but rated slow brushing as more pleasant than fast brushing (Z = −2.01, p = 0.04). Relative to the Vertex session, intensity ratings decreased after S2 rTMS for fast brushing (Wilcoxon signed rank test, Z = 1.7, a priori one-tailed p = 0.045) but not for slow brushing (Z = 0.18, one-tailed p = 0.429). There was no significant difference between brushing locations. Change in pleasantness ratings did not differ between S2 rTMS and Vertex rTMS for fast brushing (Z = −0.58, one-tailed p = 0.281) or slow brushing (Z = −0.17, one-tailed p = 0.433) (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Baseline intensity and pleasantness ratings of gentle brushing. There were no differences by hand location or session so ratings were collapsed across locations and sessions. Median ratings are displayed; error bars represent interquartile intervals. * = two-tailed p < 0.05.

Figure 5.

Changes in participants’ median ratings of fast and slow brushing intensity (top) and pleasantness (bottom) from before to after rTMS to S2 or Vertex. Error bars display interquartile intervals. Participants rated fast brushing as significantly more intense after rTMS to S2. No changes were found in pleasantness perception.

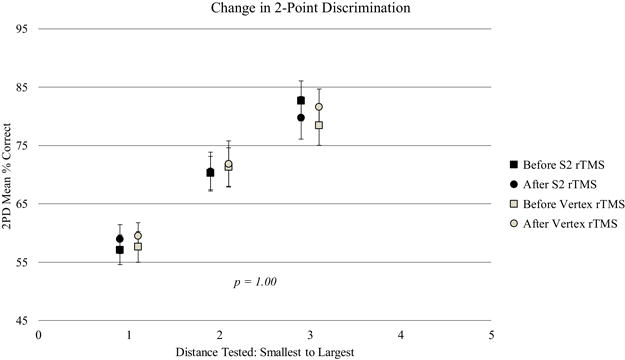

No Effect of S2 rTMS on 2PD accuracy

Accuracy of 2PD was not affected by rTMS to either S2 or vertex, with no overall effect of rTMS location (F(1, 24.85 = 0.00, p = 1.00), and no interaction between distance and rTMS location (F(2, 28) = 0.74, p = 0.48) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Changes in two-point discrimination (2PD) task performance from before to after S2 or Vertex rTMS. Error bars display ± SEM. No changes were found in tactile discrimination from the rTMS sessions.

No effect of rTMS on pain or mood

rTMS had no significant effect on ratings of good mood, bad mood, anxiety, or calmness (Table 2) and no difference between rTMS locations [good mood (t(18) = 0.44, p = 0.67), bad mood (t(18) = 0.18, p = 0.86), anxiety (t(18) = 0.92, p = 0.37), calm (t(18) = 2.04, p = 0.06)]. Participants experienced transient scalp pain during both rTMS stimulation locations (S2: 34.6 +/−30.5; vertex 23.3 +/−26.0) with no difference between locations (t(18) = 1.07, p = 0.30).

Table 2.

Mood and pain ratings.

| rTMS | good mood | bad mood | anxiety | calm | pain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before S2 rTMS | 7.6 (SD 1.1) | 0.6 (SD 1.0) | 0.6 (SD 1.0) | 8.3 (SD 1.3) | |

| After | 7.0 (SD 1.2) | 1.0 (SD 0.9) | 0.7 (SD 0.9) | 7.9 (SD 1.4) | 34.6 (SD 30.5) |

| Before Vertex rTMS | 7.5 (SD 1.1) | 0.6 (SD 1.0) | 0.9 (SD 1.4) | 7.4 (SD 1.8) | |

| After | 6.9 (SD 1.4) | 0.9 (SD 1.0) | 0.7 (SD 1.2) | 7.8 (SD 1.2) | 23.3 (SD 26.0) |

Discussion

We used inhibitory rTMS to test the causal role of S2 in perception of gentle touch intensity and pleasantness. The fRMI results revealed a bilateral reduction in S2 brush-evoked activation, with no change in insular or S1 activation, suggesting that we had preferentially altered tactile responsiveness in S2. During this S2 deactivation, subjects reported reduced perceived intensity of brushing stimuli, without changes in pleasantness or two-point discrimination. No such effects were observed with vertex rTMS. Together, these findings support our primary hypothesis that S2 plays a critical role in tactile intensity perception, but do not lend support to the secondary hypothesis that S2 is important for touch pleasantness.

Our results are consistent with findings that S2 plays a greater role than S1 in dynamic temporal discrimination but not in spatial localization [21]. Since we previously showed that rTMS deactivation of S1 worsened tactile spatial discrimination, while paradoxically increasing the perceived intensity of a tactile stimulus, the current findings suggest a very different role for S2 in tactile perception. We previously suggested that the increased intensity perception following S1 rTMS [17] may have resulted from S1 inhibition leading to S2 disinhibition. The current findings of S2 involvement in perceived touch intensity support that idea.

Our current results fit with the broader literature tying S1 to spatial discrimination and S2 to intensity perception. Extensive research has identified the role of S1 cortex in discriminative aspects of somatosensation, including tactile detection thresholds [4, 8], frequency discrimination [30], 2PD [18, 30–32] tactile direction discrimination [34], and spatial discrimination [22]. In contrast, intensity, attention and salience of somatosensory stimuli have been more closely associated with S2 (e.g. [1, 6, 9, 14]). S2 BOLD also appears to reach its maximal response at lower levels of stimulus intensity than S1 [16, 20, 37].

In contrast to the effect of S2 rTMS on intensity perception, we did not observe any effect of S2 rTMS on perception of touch pleasantness. We believe our testing paradigm is sensitive to fairly subtle manipulations, as we previously showed, using the same techniques, that the mu-opioid receptor antagonist naloxone can increase touch pleasantness without altering touch intensity [38]. S2 has not generally been associated with pleasantness perception, although it has been implicated in attention and salience of stimuli (e.g. [1, 3, 6]). A recent meta-analysis conducted by Morrison suggests that S2 shows a high likelihood of fMRI activation for affective aspects of touch as well as discriminative aspects [25] Nevertheless, because studies have often not fully separated affective and discriminative factors, it is unclear whether this activation is inherently affective or reflects processes such as attention or salience that strongly influence affective processing. Indeed, their contrast of brain regions that are significantly more likely to be activated by affective touch than by discriminative touch identified the posterior insula but not S2. This suggests that S2 may be tied only indirectly to processing of tactile pleasantness. Kress et al. [19] also report correlation between pleasantness ratings and BOLD in the contralateral pINS, with activation appearing to border between S2 and the insula [25]. Further, in both our study and these other studies, it is difficult to know what aspects of touch perception participants take into account when rating intensity and pleasantness (e.g. perceptions of velocity, arousal, comfort, etc).

We did not see a significant effect of S2 rTMS on BOLD response to brushing in whole-brain fMRI analysis. However, it is difficult to capture the effect of TMS with fMRI. Our fMRI scan did not begin until approximately 20 minutes after the end of rTMS, and cortical inhibition may have partially worn off by this time (e.g. [36]). Still, given the difficulty of capturing TMS effects with fMRI, it is significant that we detected the rTMS effect with ROI analyses, demonstrating inhibition of contralateral and ipsilateral S2 after S2 rTMS.

It is also interesting that our unilateral rTMS produced a bilateral reduction of touch-evoked S2 activation. Unilateral afferent input activates S2 bilaterally, with a serial flow of information from contralateral S2 to ipsilateral S2 following activation of S1 [7, 15, 36]. This transcallosal information flow could underlie the bilateral inhibitory effect.

Our fMRI data support the idea that S2 cortex was affected by the rTMS, without significant effects on pINS or other sensory brain regions. Nevertheless, we cannot completely exclude the possibility of sub-threshold effects in other regions that could contribute to the observed sensory changes. We used the H8, an H-coil designed for deep-brain stimulation in order to reach the entire parietal operculum. Insula stimulation with deep TMS has been reported by de Andrade et al. using a Magventure cooled DB-80 butterfly coil [2], but has not been reported with the H-coil. We believe that our sensory and fMRI results support the claim of the manufacturer that at 120% of MT, the H8 produces 100V/m up to 3.5 cm (Zangen and Roth, personal communication). A slightly shorter stimulation distance would be expected for our stimulation intensity of 110%. However, it is still possible that subthreshold stimulation might affect the insula.

In summary, rTMS over right S2 reduced bilateral S2 BOLD response to gentle brushing and reduced perception of the intensity of fast brushing, with no effect on touch pleasantness or two-point discrimination. Together, these results suggest an important role of S2 in touch intensity perception.

Highlights.

1-Hz inhibitory rTMS conducted over secondary somatosensory cortex (S2) or vertex

rTMS to S2 decreased ratings of touch intensity for fast but not slow brushing

rTMS to S2 did not alter touch pleasantness or tactile discrimination

Somatosensory BOLD response in S2 was reduced after S2 Rtms

Results suggest S2 is causally involved in touch intensity perception

rTMS over S2 using H8 deep TMS coil did not reach insula

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research program of the NIH, National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Backes W, Mess W, van Kranen-Mastenbroek V, Reulen J. Somatosensory cortex responses to median nerve stimulation: fMRI effects of current amplitude and selective attention. Clinical neurophysiology. 2000;111:1738–1744. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(00)00420-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caminiti R, Innocenti GM, Manzoni T. ANATOMICAL SUBSTRATE OF CALLOSAL MESSAGES FROM SI AND SII IN THE CAT. Experimental Brain Research. 1979;35:295–314. doi: 10.1007/BF00236617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Case LK, Čeko M, Gracely JL, Richards EA, Olausson H, Bushnell MC. Touch perception altered by chronic pain and by opioid blockade, eneuro 3 (2016) ENEURO. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0138-15.2016. 0138–0115.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Case LK, Laubacher CM, Olausson H, Wang B, Spagnolo PA, Bushnell MC. Encoding of Touch Intensity But Not Pleasantness in Human Primary Somatosensory Cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2016;36:5850–5860. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1130-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen R, Classen J, Gerloff C, Celnik P, Wassermann E, Hallett M, Cohen L. Depression of motor cortex excitability by low‐frequency transcranial magnetic stimulation. Neurology. 1997;48:1398–1403. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.5.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen TL, Babiloni C, Ferretti A, Perrucci MG, Romani GL, Rossini PM, Tartaro A, Del Gratta C. Human secondary somatosensory cortex is involved in the processing of somatosensory rare stimuli: an fMRI study. NeuroImage. 2008;40:1765–1771. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung YG, Han SW, Kim HS, Chung SC, Park JY, Wallraven C, Kim SP. Intra- and inter-hemispheric effective connectivity in the human somatosensory cortex during pressure stimulation. Bmc Neuroscience. 2014;15 doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-15-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen LG, Bandinelli S, Sato S, Kufta C, Hallett M. Attenuation in detection of somatosensory stimuli by transcranial magnetic stimulation. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology/Evoked Potentials Section. 1991;81:366–376. doi: 10.1016/0168-5597(91)90026-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corkin S, Milner B, Rasmusse T. SOMATOSENSORY THRESHOLDS - CONTRASTING EFFECTS OF POSTCENTRAL-GYRUS AND POSTERIOR PARIETAL-LOBE EXCISIONS. Archives of Neurology. 1970;23:41. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1970.00480250045007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davidovic M, Jönsson EH, Olausson H, Björnsdotter M. Posterior superior temporal sulcus responses predict perceived pleasantness of skin stroking. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2016;10 doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fitzgerald PJ, Lane JW, Thakur PH, Hsiao SS. Receptive field (RF) properties of the macaque second somatosensory cortex: RF size, shape, and somatotopic organization. Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26:6485–6495. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5061-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hallett M. Transcranial magnetic stimulation: a primer. Neuron. 2007;55:187–199. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsiao S. Central mechanisms of tactile shape perception. Current opinion in neurobiology. 2008;18:418–424. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsiao SS, O’shaughnessy D, Johnson KO. Effects of selective attention on spatial form processing in monkey primary and secondary somatosensory cortex. Journal of neurophysiology. 1993;70:444–447. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.1.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu L, Zhang ZG, Hu Y. A time-varying source connectivity approach to reveal human somatosensory information processing. Neuroimage. 2012;62:217–228. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jousmäki V, Forss N. Effects of stimulus intensity on signals from human somatosensory cortices. Neuroreport. 1998;9:3427–3431. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199810260-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalberlah C, Villringer A, Pleger B. Dynamic causal modeling suggests serial processing of tactile vibratory stimuli in the human somatosensory cortex—An fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2013;74:164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knecht S, Ellger T, Breitenstein C, Ringelstein EB, Henningsen H. Changing cortical excitability with low-frequency transcranial magnetic stimulation can induce sustained disruption of tactile perception. Biol Psychiat. 2003;53:175–179. doi: 10.1016/s0006322302013823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kress IU, Minati L, Ferraro S, Critchley HD. Direct skin-to-skin vs indirect touch modulates neural responses to stroking vs tapping. Neuroreport. 2011;22:646. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328349d166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin YY, Shih YH, Chen JT, Hsieh JC, Yeh TC, Liao KK, Kao CD, Lin KP, Wu ZA, Ho LT. Differential effects of stimulus intensity on peripheral and neuromagnetic cortical responses to median nerve stimulation. Neuroimage. 2003;20:909–917. doi: 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00387-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lockwood PL, Iannetti GD, Haggard P. Transcranial magnetic stimulation over human secondary somatosensory cortex disrupts perception of pain intensity, cortex. 2013;49:2201–2209. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lundblad LC, Olausson HW, Hermansson AK, Wasling HB. Cortical processing of tactile direction discrimination based on spatiotemporal cues in man. Neuroscience letters. 2011;501:45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maeda F, Keenan JP, Tormos JM, Topka H, Pascual-Leone A. Modulation of corticospinal excitability by repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. Clinical neurophysiology : official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2000;111:800–805. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(99)00323-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCabe C, Rolls ET, Bilderbeck A, McGlone F. Cognitive influences on the affective representation of touch and the sight of touch in the human brain. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience. 2008;3:97–108. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsn005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morrison I. ALE meta-analysis reveals dissociable networks for affective and discriminative aspects of touch. Human brain mapping. 2016;37:1308–1320. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rossi S, Hallett M, Rossini PM, Pascual-Leone A, S.o.T.C. Group Safety, ethical considerations, and application guidelines for the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation in clinical practice and research. Clinical neurophysiology. 2009;120:2008–2039. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roth Y, Amir A, Levkovitz Y, Zangen A. Three-dimensional distribution of the electric field induced in the brain by transcranial magnetic stimulation using figure-8 and deep H-coils. Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2007;24:31–38. doi: 10.1097/WNP.0b013e31802fa393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruben J, Schwiemann J, Deuchert M, Meyer R, Krause T, Curio G, Villringer K, Kurth R, Villringer A. Somatotopic organization of human secondary somatosensory cortex. Cerebral Cortex. 2001;11:463–473. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.5.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rudiak D, Marg E. Finding the depth of magnetic brain stimulation: a re-evaluation. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology/Evoked Potentials Section. 1994;93:358–371. doi: 10.1016/0168-5597(94)90124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Satow T, Mima T, Yamamoto J, Oga T, Begum T, Aso T, Hashimoto N, Rothwell J, Shibasaki H. Short-lasting impairment of tactile perception by 0.9 Hz-rTMS of the sensorimotor cortex. Neurology. 2003;60:1045–1047. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000052821.99580.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seyal M, Siddiqui I, Hundal NS. Suppression of spatial localization of a cutaneous stimulus following transcranial magnetic pulse stimulation of the sensorimotor cortex. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology/Electromyography and Motor Control. 1997;105:24–28. doi: 10.1016/s0924-980x(96)96090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simons D, Puretz J, Finger S. Effects of serial lesions of somatosensory cortex and further neodecortication on tactile retention in rats. Experimental brain research. 1975;23:353–365. doi: 10.1007/BF00238020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Johansen-Berg H, Bannister PR, De Luca M, Drobnjak I, Flitney DE. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage. 2004;23:S208–S219. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tegenthoff M, Ragert P, Pleger B, Schwenkreis P, Förster A-F, Nicolas V, Dinse HR. Improvement of tactile discrimination performance and enlargement of cortical somatosensory maps after 5 Hz rTMS. PLoS biology. 2005;3:e362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thielscher A, Kammer T. Linking physics with physiology in TMS: a sphere field model to determine the cortical stimulation site in TMS. NeuroImage. 2002;17:1117–1130. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thut G, Pascual-Leone A. A review of combined TMS-EEG studies to characterize lasting effects of repetitive TMS and assess their usefulness in cognitive and clinical neuroscience. Brain topography. 2010;22:219. doi: 10.1007/s10548-009-0115-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Timmermann L, Ploner M, Haucke K, Schmitz F, Baltissen R, Schnitzler A. Differential coding of pain intensity in the human primary and secondary somatosensory cortex. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2001;86:1499–1503. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.3.1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Torquati K, Pizzella V, Della Penna S, Franciotti R, Babiloni C, Rossini PM, Romani GL. Comparison between SI and SII responses as a function of stimulus intensity. Neuroreport. 2002;13:813–819. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200205070-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zangen A, Roth Y, Voller B, Hallett M. Transcranial magnetic stimulation of deep brain regions: evidence for efficacy of the H-coil. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2005;116:775–779. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]