Abstract

Clinical photodynamic therapy (PDT) has existed for over 30 years, and its scientific basis has been known and investigated for well over 100 years. The scientific foundation of PDT is solid and its application to cancer treatment for many common neoplastic lesions has been the subject of a huge number of clinical trials and observational studies. Yet its acceptance by many clinicians has suffered from its absence from the undergraduate and/or postgraduate education curricula of surgeons, physicians, and oncologists. Surgeons in a variety of specialties many with years of experience who are familiar with PDT bear witness in many thousands of publications to its safety and efficacy as well as to the unique role that it can play in the treatment of cancer with its targeting precision, its lack of collateral damage to healthy structures surrounding the treated lesions, and its usage within minimal access therapy. PDT is closely related to the fluorescence phenomenon used in photodiagnosis. This review aspires both to inform and to present the clinical aspect of PDT as seen by a surgeon.

Keywords: PDT in oncology, PDT for surgeons

At the dawn of the 20th century, Oscar Raab studied the effects of acridine on paramecia cultures in Munich's Laboratories of Von Tappeiner, noting that in the dark acridine had no harmful effect on the growth of this protozoan microorganism, but once exposed to the light, it became lethal to paramecium.1 A more detailed study of the mechanisms involved indicated the killing process depended on oxygen in addition to light. The process was named Photodynamische Wirkung.2 3 4 This work has been variably translated in English as photodynamic effect, photodynamic phenomenon, and photodynamic reaction (PDR). It was, in fact, a complex cell-killing phenomenon resulting from the interaction of a chemical compound, a photosensitizer (PS), light, and oxygen. The discovery of Photodynamische Wirkung led von Tappeiner and colleagues to set up a clinical experiment in six patients with skin cancer and thus moved from laboratory level of Photodynamische Wirkung to the Photodynamische Therapie, or photodynamic therapy (PDT). In this article, the term photodynamic reaction is used to mean the events that lead to the killing of cells in vitro and within a laboratory setting resulting from the interaction of the PS with light in the presence of oxygen. In contrast, the term photodynamic therapy is reserved to mean the combination of PS, light, and oxygen in an in vivo clinical environment. There are associated events modulating the PDR and adding to the complexity of the process to achieve the therapeutic objectives of destruction of unwanted diseased tissue such as cancer. PDT is principally a local treatment dependent on the localization of a chemical agent (the drug) in diseased cells, presensitizing them to a specific light wavelength. The extent of injury and cell death is determined by the dimensions of the presensitized tissue and the physical characteristic of the light.

Many early researchers were aware of the fact that the interaction between light and PSs within the cells not only produced PDR but also led to another related process, namely fluorescence emission. It was also clear that in an in vivo situation the relative simplicity of the laboratory trio of PS, light, and oxygen interactions become an “opera” of gigantic magnitude with the involvement of several interrelated phenomena. PDR and fluorescence emission are in reality two facets of the same process of light–tissue interaction. The manner in which light interacts with a specific type of tissue is dictated by wavelength-dependent absorption and scattering properties. In the ultraviolet and visible spectrum, tissue optical properties are dominated by endogenous chromophores, which differ in normal and abnormal tissues of the same type. The principal chromophore in human tissues is hemoglobin, which has strong absorption at wavelengths shorter than 600 nm. Other components not only absorb light over specific bands between 250 and 500 nm but also display characteristic fluorescent emission over the range of 300 to 700 nm. Fluorescent emission is the absorption of an incident light at one wavelength followed by emission of a light at a different (usually higher) wavelength, which ceases almost immediately when the incident radiation stops.

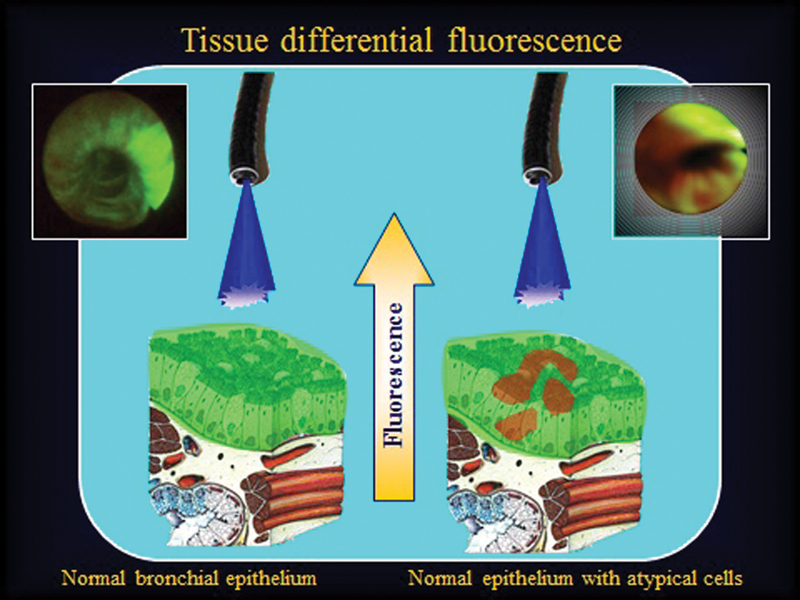

Some tissues exhibit a characteristic fluorescent emission band that is altered when a disease process such as cancer occurs, changing their molecular structures and thus their chromophore components. By using an appropriate wavelength of light, usually within the blue region, one can display the differential fluorescence images, which is the basis of autofluorescence photodiagnosis (PD) (Fig. 1).5 6 Although PD does not equate to the diagnosis of a specific disease, it is nevertheless an indication of local changes, highlighting the best biopsy location to provide histologic diagnosis. The phenomenon of fluorescence can also be enhanced by using an exogenous fluorophore such as a PS. Such an enhanced PD is useful particularly to surgeons to indicate residual neoplastic infiltration, which may exist at the margin of resection. It may even guide the surgeon in some areas, such as brain surgery, in removal of tumor residue invisible to the naked eye or to microscopic operative devices.7

Fig. 1.

Diagram and bronchoscopic view of autofluorescence bronchoscopy, using blue light region (440 nm). Normal bronchial mucosa (left). Bronchial mucosa involved by carcinoma in situ (right).

In the first half of the 20th century and until 1978, clinical PDT was performed in a few institutions within an experimental setting, building up the parameters for a given therapy.8 9 The initial series of clinical trials was performed by Dougherty and colleagues after synthesis of a porphyrin-based PS hematoporphyrin derivative (HPD).10 The trial involved 111 patients with different types of cancers. The immediate results impressively showed that every patient responded to treatment. After this initial success, the problem was to synthesize more PSs, to determine light dose for specific lesions, and to devise methods of illumination of tumors situated within the body rather than on its surface.

The modern era of clinical PDT began in earnest in the early 1980s with the availability of a more refined formulation of HPD, Photofrin. Also, new second-generation drugs and prodrugs were synthetized.11 12 13 Within the next 15 to 20 years, the number of PSs grew, many of which did not leave the laboratory shelves and never ever saw the light of clinical practice. Although efforts continued to synthesize better PSs, there was also development in matching light sources and lasers.14

Mechanisms of Photodynamic Therapy

The groundbreaking work in PDR and PDT by Munich's scientists over a century ago was followed by intense research by many scientists and laboratories throughout the world to unravel the intricacies of the interaction between the three components of PDT that culminate in the death of the cells under attack.15 16 17

It was clear from the beginnings of PDT that, in complex biological systems such as mammalians and the human body where there are many different cells, tissues, and organs, there is a functional as well as structural interdependence between various groups of tissues that make up different organs. Therefore, PDT though a local phenomenon would affect other parts of the body away from the site of treatment through activation of mechanisms related to general response to injury and via stimulation of the immune system.17 18 PDT in a human subject will inevitably involve different sets of phenomena than those in a controlled laboratory environment often concerned with one cell. PDT response in the clinical situation involves several separate and yet related events that can be described under three headings:

Direct local injury to the target tissues by the cytotoxic agents released through the PS–light–oxygen interaction, essentially but not entirely related to reactive oxygen species leading to necrosis or accelerated apoptosis

PDT damage to vasculature that further enhances necrosis of the targeted lesion by deprivation of oxygen and essential molecules18 19

PDT stimulation of inflammatory and immune responses that assist the body toward the destruction of unwanted tissues locally as well as altering the immunologic competence more generally16 17 18 19

Clinical Photodynamic Therapy Components and Devices

Clinical PDT harnesses the three ingredients of PDR and focuses them to a target area, destroying the cells and tissues that make up a lesion. The three components of clinical PDT are basically those used in a laboratory and experimental setting with several provisos and modifications to suit the human clinical situation: the PS, an appropriate light, and oxygen.

The Photosensitizer

The PS is a chemical compound that can localize in the abnormal cells, such as cancer. For human usage, a PS has to comply with the requirements of safety and the licensing authorities. Table 1 shows the family of PSs available for clinical practice, which is not a complete, universally agreed upon, or accepted list of PSs, but comprises those used in many countries.

Table 1. Common photosensitizers in use for clinical PDT in oncology (manufacturers and web sites listed in Appendix 1).

| Family | Name | Alternative/Abbreviation | Activation light (nm) | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porphyrin | Hematoporphyrin derivative | HpD | 630 | Precursor of Photofrin |

| Porphyrin | Photofrin | Porfimer sodium | 630–635 | Multipurpose |

| Porphyrin (prodrug) | Levulan | 5-ALA | 630 | Topical/skin |

| Porphyrin (prodrug) | Metvix | Methyl-ALA | 630 | Mainly skin |

| Porphyrin (prodrug) | Visudyne | Verteporfin | 619 | Experimental for oncology |

| Porphyrin (prodrug) | Hexaminolevulinate hydrochloride | HALA | Fluorescence cystoscopy | |

| Texaphyrin | Lutexaphyrin/lutetium texaphyrin | Lutex, Optrin | 730 | Experimental, clinical |

| Chlorin | Foscan | mTHPC | 525–660a | Head and neck, others/variable |

| Chlorin | Talaporfin | |||

| Chlorin | NPe6 | Mono-L-aspartyl chlorin 6 | 664 | Lung cancer |

| Chlorin | Photochlor | HPPH | 665–680 | |

| Bacteriochlorin | TOOKAD | Metal complex bacteriochlorin | 760 | Vascular targeted, prostate |

| Dye | Photosens | Phthalocyanine | 650–850 | Various |

Abbreviations: ALA, aminolevulinic acid; mTHPC, meso-tetraphenyl chlorine; PDT, photodynamic therapy; TOOKAD, Pd-bacteriopheophorbide.

Esophagus.

Appendix 1. Photosensitisers, manufacturers, and web sites.

| Photosensitiser | Manufacturer | Web site |

|---|---|---|

| Hematoporphyrin derivative | Variable in different countries | Currently used in laboratories (see Ref. 11) |

| Photofrin | Pinnacle Biologics, Chicago, Illinois, United States | www.pinnaclebiologics.com |

| Levulan | DUSA Pharmaceuticals,Wilmington, Massachusetts, United States | www.dusapharma.com |

| Metvix | Galderma Pharma SA | www.galderma.com |

| Visudyne | Verteporfin | www.visudyne.com |

| Hexaminolevulinatehydrochloride | Photocure | www.photocure.com |

| Letexaphyrin/lutetium texaphyrin | Pharmacyclics, Inc. | www.pharmacyclics.com |

| Foscan | Biolitec Technology Gmbh | www.biolitec.com |

| Talaporfin | Light Science Oncology, Bellevue, Washington,United States | info@tacomaradiation.com |

| Photochlor | AdooQ Bioscience, Irvine, California, United States | info@adooq.com |

| TOOKAD | Steba Biotech | info@stebabiotech.com |

| Photosens | General Physics Institute | www.gpe.ru |

Provision of chemical structure and characteristics of PSs is not within the scope of this article. These are described in most textbooks on PDT and reviews.20 21 Nevertheless, it is relevant to point out that PSs may be classified into two groups: systemic PS and topical PS.

Topical and systemic PDTs and their respective PSs are variations of the same process and their mechanisms follow similar patterns. However, they have different indications and different applications and often use different light sources. Furthermore, the two groups are endowed with their respective advantages and disadvantages.

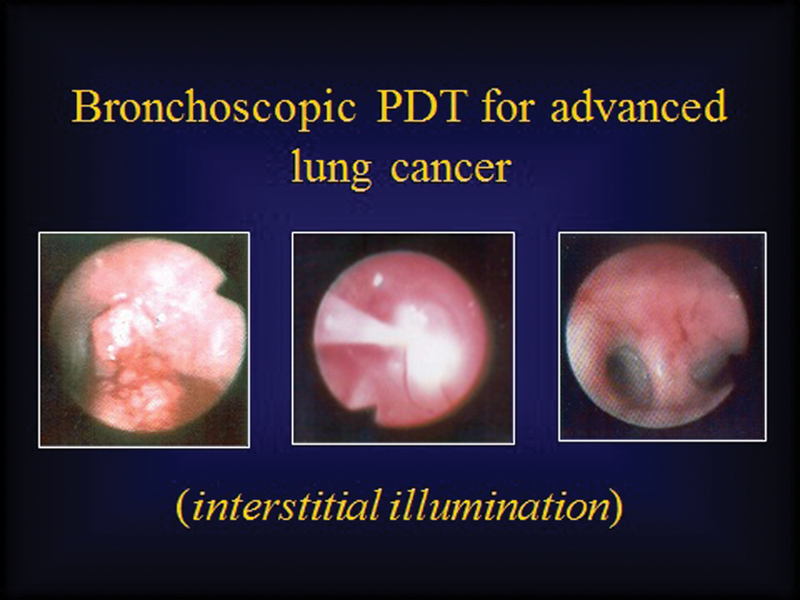

Systemic Photodynamic Therapy and Photosensitizers

As a general rule, systemic PDT (exemplified by Photofrin PDT, Table 1) uses intravenous (IV) route of administration of the PSs. These directly enter the circulatory system and reach the target tissue through the bloodstream. Systemic photosensitization by routes other than IV has remained within the domain of experimentation and is not routinely used by PDT clinicians. Systemic photosensitization/PDT ensures wide distribution of the PS, albeit with a higher concentration in neoplastic tissues than normal. It also allows multiple-site illumination, multiple-site PDT, and at-depth illumination, either using an appropriate wavelength of light with deeper penetration or by applying interstitial illumination (light exposure, Fig. 2). PDT can be performed intraoperatively in conjunction with standard or minimal access surgery.

Fig. 2.

Bronchoscopic view of a tumor obstructing the opening of left upper lobe bronchus treated by interstitial illumination. Far left: tumor in the left upper lobe bronchus; middle: illumination of the tumor; right: bronchoscopic view of the upper lobe bronchus 6 weeks after photodynamic therapy (PDT) showing complete clearance.

The main disadvantage is the potential prolonged skin photosensitivity of up to 8 to 10 weeks for some PSs of the porphyrin family, thus potentially adversely affecting the quality of life of the patient.

Topical Photodynamic Therapy

Topical PDT includes use of the prodrug 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) or its variants (see Table 1), which, after administration, is converted to protoporphyrin IX, the actual PS. By using ALA PDT topically, the PS protoporphyrin IX is synthesized locally and does not enter into the bloodstream. This approach, however, only reaches tissues within the depth of ∼1 mm from the point of administration. Because topical ALA uptake is so limited, irrespective of the type of light used, photodynamic injury and effects are limited in extent and depth. It also follows that photodynamic skin reaction is limited to the area of treated area.

Appropriate Light

An appropriate light has a wavelength that matches the characteristics of the PS and is therefore capable of its excitation (activation), which in many instances will have to be a laser capable of generating light of a specific wavelength and emitting variable power to match the requirements of tissues of different optical characteristics. Alternatively, LED may be used for superficial lesions. The currently available PSs used in clinical PDT practice are activated by light within the wavelengths of the visible electromagnetic spectrum, 400 to 700 nm.

Table 2 shows the wavelength ranges and the corresponding colors from violet to red as well as the light penetration through the skin in function of wavelength and color. The depth of light transmission in a given tissue or organ is an important aspect of the clinical PDT procedure. This aspect is particularly relevant in the case of organs endowed with a rich vasculature, such as an artery, during the course of illumination in PDT, which could lead to an uncontrollable fatal hemorrhage. Determination of light penetration in a given tissue or organ in clinical PDT practice is based on the ex vivo mathematical calculation of parameters involved in optophysics of light–tissue interaction and in vivo studies of animals and humans.22 23 However, in the final analysis the appropriate measurement in clinical cases and experience of clinicians need to be considered. The general principles that govern the depth or the radius of light transmission in a given organ depend on light factors and tissue factors. As a general rule, the longer the wavelength, the deeper/or wider the light will be transmitted. The higher the power and power density (fluence) settings, the deeper the transmission.

Table 2. Wavelength of visible lights spectrum and depth of penetration (human skin).

| Color | Wavelength (nm) | Penetration depth (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Red | 622–780 | 4–10 |

| Orange | 597–622 | 3–4 |

| Yellow | 577–597 | 3 |

| Green | 492–577 | 2 |

| Blue | 455–492 | 1 |

| Violet | 390–455 | 1 |

Tissue factors relate to the optical properties of tissues exposed to the light. In humans, the optical properties of an organ result from a mix of heterogeneously structured component tissues, which are a complex summation of ratio of absorption and the scattering of each participating tissue. The relative penetration in skin of different wavelengths of visible light can be seen in Table 2. It is nevertheless important to realize that the reported penetration in the skin does not hold true for other tissues or organs whose complex optical properties are not similar to those of the skin. For instance, in the case of bronchial mucosal wall and pulmonary tissues, the red light (630 nm) penetrates up to 10 mm. In practice, the PDT team should include a clinical physicist or a clinician knowledgeable in optical physics.

From a clinical point of view, the laser device requires a connection for delivery of optical fibers for light emission. The fibers should be of suitable diameter to be accommodated within the delivery channels of endoscopic equipment or surgical instrumentation used in various procedures.

Oxygen

The third component, oxygen, is available in all living tissues.

Clinical Photodynamic Therapy in Practice

Clinical PDT is performed as a two-step procedure:

Presensitization. The PS is administered systemically (intravenously/orally) or topically. The aim is for the PS to “localize” in the target lesion at a higher concentration than in normal tissue.

Illumination. The light is directed to the presensitized tissue/lesion area. In many instances, the light is transmitted via an optical fiber ending in a cylindrical or bulb diffuser, which emits light around its circumference. Alternatively, the fiber ends in a microlens, which provides forward emission of light.

Dosimetry of light constitutes an important issue that needs to be mastered by the clinician or clinical (medical) physicist. Between the presensitization and illumination steps, there needs to be a latent period to allow distribution and localization to take place of the PS within the cells/tissues of the lesion.

The Potentials of Photodynamic Therapy in Clinical Practice

PDT uses minimally invasive techniques and, due to its dependence on PS and matching light, its direct effect is limited to the area of presensitized tissue that is exposed to the appropriate matching light. In this respect, PDT differs from all other local cancer therapy methods because it has a double targeting mechanism. The first is the operator directing the light to the target. The second is the ability of the light with its specific wavelength that matches the absorption characteristics of the PS to “lock” into the presensitized tissues of the target. Therefore, PDT affects the target tissue more precisely with little or no collateral damage to the normal tissue outside the range of the light transmission within illuminated areas. It is repeatable; there is no evidence of development of resistance in target lesions.

PDT can be used within a multidisciplinary setting. It may be incorporated within a combination therapy schedule to be used with or after chemoradiation and surgery. In certain cases, it may be used as a neoadjuvant therapy to downstage the cancer before surgical operation. It may be used in the early stage of several neoplasms with a curative intent. PDT can be used in locally advanced stages of many cancers to achieve palliation of symptoms.

Clinical Indications of Photodynamic Therapy

For descriptive purposes, the many indications of PDT in clinical practice may be grouped under (1) oncological indications, relating to the destruction of cancer tissues, which is currently the principal indication of PDT, and (2) nononcological indications.

Photodynamic Therapy in Oncology: A Classification

There are over 5,000 publications concerned with PDT in patients with cancers in different sites. A clinician in a given specialty who considers using PDT for a patient with cancer needs a benchmark that indicates the effectiveness as well as the appropriateness of the treatment for the case under consideration. Such a benchmark can only be provided by review of large numbers of cases reported by experienced clinicians giving the details of techniques. Systematic reviews, with their strict criteria, are considered by some to be the gold standard, but do they fit the purpose? In the real world of clinical practice, the effectiveness and appropriateness of PDT for a given case of cancer does not always, or even often, coincide with systematic review findings. Systematic reviews are more often based on controlled clinical trials and statistical significance rather than the clinical relevance in case series and observational studies or small-scale clinical trials compiled by specialist clinicians engaged in PDT. This fact becomes abundantly clear when one with a background of experience, involvement, and clinical skills looks at some of the published systematic reviews and their conclusions.24

Some of the existing systematic reviews in PDT have not been able to validate PDT for almost any clinical situation in oncology, despite many thousands of publications concerned with clinical trials, case series, and observational studies performed by experienced clinicians of repute in their specialties.24 25 In the face of such a discrepancy, clinicians must carry on with their duty of care and treat patients with PDT when, according to their experience or that of their peers, the treatment can help.

We have reviewed a large number of publications related to the use of PDT in different cancers, empirically but rationally placing them into three league tables according to the following criteria:

Clinical effectiveness of PDT related to the particular type of cancer as judged by the results portrayed in a publication

Standardization of the methodology of PDT used in a given cancer

Reproducibility of results by different clinicians using an established methodology for the type of cancer under the review

Number of patients and publications for a given cancer in which PDT was used

In reviewing publications for each of the above parameters, we allocated a grade from 1 (+) to 3 (++ + ) points: where 1 (+) was the lowest, and the 3 (++ + +), the highest.

The aim of this compilation was to see at a glance the current status and relative usage of PDT in a given type of cancer within the overall PDT in oncology.

Results of the Review

Based on the above criteria and parameters, we identified groups of cancer types and based on their scores placed them in three leagues represented in Tables 3, 4, and 5.

Table 3. League I PDT clinical classification.

| PDT indications | Initial studies | Reproducibility | Publications | Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Head and Neck/ENT | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ |

| Lung Ca. | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Barrett's esophagus | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Esophageal Ca. | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

Abbreviations: Ca, cancer; ENT, ear, nose, and throat; PDT, photodynamic therapy.

Table 4. League II PDT clinical classification.

| PDT indications | Initial studies | Reproducibility | Publications | Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cholangiocarcinoma | ++ | +/ + + | + | +/ + + |

| Mesothelioma | ++ | + | + | + |

| Brain tumors | ++ | ++ | + | + |

| Urology (prostate, bladder) | + | −+ | + | + |

Abbreviation: PDT, photodynamic therapy.

− = none; −+ = none or a small number less than 10 publications.

Table 5. League III PDT clinical classification.

| PDT indications | Initial studies | Reproducibility | Publications | Method | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gynecology CIN VIN Ovary |

++ ++ + |

+ ++ − |

+/ + + + −+ |

+ + − |

– Experimental only |

| Breast Primary Chest wall recurrence |

−+ + |

− + |

+ + |

− + |

Laboratory/experimental (see text) |

| Pancreas | −+ | − | −+ | − | Experimental |

| Intraperitoneal | + | − | − | − | Experimental |

Abbreviations: CIN, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, VIN, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia; PDT, photodynamic therapy.

− = none; −+ = none or a small number less than 10 publications.

League I

There are five types of cancers in this league: skin, lung, head and neck, Barrett's esophagus, and esophageal. From a clinical point of view, the methodology is in place for all these cancers, and there is a consensus of “how to do it” agreed upon by specialist physicians and surgeons engaged in practice.

Skin Cancers and Precancerous Lesions

Skin tumors were the subject of initial experiments of PDT in humans. The reasons are principally related to ease of application, notably in the illumination method, feasibility of monitoring progress, and assessing the results.

Many skin cancers are surgically excised, and surgery is still the treatment of choice and an attractive option for patients. However, for those with multiple lesions and/or with tumors in specific locations, such as the face, the alternative use of PDT appears more appealing to many. Also, it is generally agreed that for the immunosuppressed patient (organ transplant recipients, for example), those with a lesion near the orbit, and cases with Gorlin syndrome, PDT has more to offer than surgery.26 27

PDT in skin cancers other than melanomas has generated ∼900 publications, many based on studies within controlled clinical trial protocols, with several books and a few guidelines.28 29 Photofrin and ALA or its derivative, methyl aminolevulinate, are the main PSs in use in Europe and North America. In other countries, notably China, the equivalent homemade formulation is used. The main skin cancers and procancers for which PDT has received approval in many of countries are:

Actinic keratosis, with response rates between 75 and 89% with topical ALA PDT30 31 32

Bowen disease (in situ squamous cell carcinoma), with complete response of 80 to 100%33 34

Basal cell carcinoma, with complete response of 80 to 90 and recurrence rate of ∼10% at 5 years34 35 36

Multiple basal cell carcinoma within Gorlin syndrome

In many patients, more than one treatment session will be required.

Many of the studies related to PDT in dermatologic cancers have been controlled clinical trials involving ALA or methyl-ALA versus other standard methods; PDT was found to have better all-round results and cosmesis.

In one randomized study of PDT versus surgery, immediate results related to clinical response were equal but there was no recurrence in the surgery group whereas the PDT group had a recurrence rate of ∼10% at 1-year follow-up. Nevertheless, patient satisfaction and cosmetic results were superior in PDT compared with surgery.37

Head and Neck

Head and neck cancers are a diverse group of tumors whose management falls within several specialties, notably maxillofacial, otorhinolaryngology, and plastic surgery. Some 550,000 cases of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck are globally diagnosed annually with 300,000 deaths.

Standard treatment for head and neck cancers is surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy. Nevertheless, there is still a need for a reliable local therapy to fill the gap in the standard methods of therapies for cases of recurrence after surgery, or when chemoradiation may not be indicated or has been used without success. In the early stages of the disease, surgery can confer long survival amounting to cure of the disease, with 5-year survival of over 80%. The overall survival is 40 to 50%.38

PDT has been used extensively in the oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx since the early 1980s.39 During the past 30 years, many hundreds of patients have been treated in various organs within the anatomical field of the head and neck. Photofrin as well as meso-tetraphenyl chlorine (mTHPC) and ALA have been employed by different investigators in many hundreds of studies.40 Indications for PDT in these cancers have been classified into:

Treatment with curative intent applicable for those with an early cancer41 42 43

Treatment of locally advanced cases where the aim is to offer patients a better quality of existence within the limited lifespan that they have44

Use as a neoadjuvant therapy and intraoperatively as an aid to a more complete resection

Treatment of local recurrence

Clinical studies have been conducted using principally Photofrinorm mTHPC (Foscan). The dose and methodology for each of these have been standardized and are well documented in the literature.45 46

Lung Cancer

Lung cancer claims nearly 1.4 million deaths per year globally,38 and surgical resection is established as its primary treatment; the long awaited use of surgery for lung cancer materialized in 1933 by Graham and Singer.47 Over the next 25 years, with a growing understanding of the oncological aspects of lung cancer, a rational attitude of selection of patients was adopted. Although surgery is considered the first modality of treatment, it can only be offered to a minority; at most, 20% of cases have cancer found early enough to offer 70% long-term survival. In effect, at presentation, between 80 and 85% of patients with lung cancer are in an advanced stage of the disease and unsuitable for surgery.

In recent years, apart from radiotherapy and chemotherapy (which are standard treatment), several other therapies, including PDT, have entered into the arena of lung cancer treatment. The objectives of PDT in lung cancer are to achieve one or more of the following: downstage the tumor, effectively acting as a neoadjuvant therapy48 49 50 51; provide a good palliation with added survival benefit in advanced diseases52 53; offer complete response for a long period in early cases54 55 56 57; treat local recurrence.57

For 70 to 80% of treated patients, PDT confers a significant improvement of exercise tolerance with parallel increase in ventilation, represented by forced vital capacity and forced expiratory volume in 1 second values and elimination of hemoptysis.58 59

In cases with early cancer, the aim of treatment is to destruct the cancer at its in situ stage of development, coupled with a long-term complete response and clearance. Review of the literature shows that between 60 and 70% of patient with early (stage 1a) cancer survive 5 years or more.

The discovery of in situ endobronchial cancer and early detection of the local recurrence are greatly assisted by autofluorescence bronchoscopy, which can provide localization of the lesion in cases where the lesion may not be visible by the usual white light bronchoscopy.60 61 62

Over 95% of PDTs in lung cancer are performed bronchoscopically for central-type lung cancer and usually for non–small cell lung cancer histology. Bronchoscopic PDT is performed in the usual two steps, that is, systemic presensitization followed by an interval of illumination using the bronchoscope's instrumental channel to accommodate the laser delivery fiber. Bronchoscopic PDT uses Photofrin (porfimer sodium) or equivalent porphyrin-derived formulations.

PDT is also used for peripheral lung cancer, for which there is limited experience. In such cases, the illumination is performed using imaging methods to localize the tumor.63 An alternative method is to use a thoracoscope to visualize the tumor and place the light delivery fiber under direct vision.64

Barrett's Esophagus and Esophageal Cancer

Barrett's esophagus refers to a condition where a variable length of the normal squamous cell mucosa of the lower esophagus, above the esophagogastric junction, is covered by columnar cell mucosa of gastric and/or intestinal-type mucosa (metaplastic mucosa). Such metaplastic mucosa is subject to dysplastic changes, which are graded as high, moderate, and low. There is a general consensus that patients with Barrett's esophagus, particularly those with high-grade dysplasia (HGD), are at risk of developing cancer. The most important issue is the relationship between HGD and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, which has been debated for almost 25 years with no sign of it abating. Many, including the senior author of this article, believe that some 40% of HGDs are already an early cancer or are found concomitantly with a cancer.65 66 67 There are also issues related to interobserver variation of diagnosis of HGD versus carcinoma in situ, as well as the liability of biopsy samples being representative of the whole metaplastic extent.68 69 We and several other surgical teams believe that in patients with long segment (>10 cm) metaplastic mucosa, particularly those with a stricture, surgery should receive serious consideration.65 66 67

Some surgeons and several patients consider that the risk of surgery with its morbidity and mortality is prohibitive to their acceptance of radical operation. In such cases, interventional endoscopy methods are an alternative treatment option. PDT, with its good track record and several hundreds of publications based on clinical trials, occupies a prominent if not the most prominent place among endoscopic methods. Used alone or with other minimally invasive methods, such as endoscopic mucosal resection, PDT has been shown to eliminate Barrett's mucosa, destroy the HGD, and potentially reduce the rate of progression to adenocarcinoma.70 71 72

Cancer of the Esophagus

Cancer of the esophagus affects over 450,000 individuals per year worldwide with 400,000 deaths.73 Over 50% of cases are surgically unresectable at diagnosis, and 80% are oncologically at a stage for which surgery cannot be undertaken with curative intent. Surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy are the standard therapies. For an early stage 1 cancer, surgical resection can achieve a 70 to 75% 5-year or greater survival.74 75

McCaughan et al used PDT for cancer of the esophagus in 1983.76 Since then, PDT has been employed in many thousands of patients for early and locally advanced stages of cancers. PDT is used in esophageal cancer for patients with locally advanced intraluminal tumors. These bulky, locally obstructive tumors cause serious symptoms. The aim of PDT is the relief of dysphagia, amelioration of nutrition, and improvement of quality of life. These objectives are achieved in the majority of PDT-treated cases.77 78 79 80 PDT is also used in patients with early mucosal tumors unsuitable for surgery. Long-term survival of 5 or more years is achieved in 50 to 60%.81 82

League II

There are four types of cancer within this league: cholangiocarcinomas, malignant pleural mesotheliomas, brain tumors, and urologic (prostate and bladder) tumors.

Cholangiocarcinoma

Cholangiocarcinoma is attended by distressing symptoms and overall poor outcome irrespective of therapy because of difficulty in diagnosing the condition in an early stage of its development. The natural history of the disease is a gradual deterioration of liver function and death by hepatic failure or cholangitis caused by biliary obstruction.

Surgery is the treatment of choice in early stages of the disease and can be accompanied by long survival or cure in 20 to 30% of cases.83 Chemoradiation is used as an adjunct to surgery.

In 1991, McCaughan et al advocated the use of PDT for the extrahepatic biliary system,84 and in 1998 Ortner et al published the first series of nine patients showing that PDT was effective in restoring biliary drainage and improving quality of life in patients with nonresectable cholangiocarcinomas who had previous insertion of stent.85 Since then, several studies have been conducted, all based on the use of a plastic or metal stent in combination with PDT. In clinical trials, different authors have shown better quality of life and longer survival of patients who received PDT combined with stent versus those having stent alone.86 87 88 89 Photofrin (porfimer sodium) has been used by the majority of investigators. However, meso-tetra-hydroxyphenyl chlorine (Foscan) has also been employed.88

Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma

Malignant pleural mesothelioma is a tumor that affects the pleural membrane of the lung. It grows slowly but relentlessly to encase the lung with a rigid crust of cancer, restricting pulmonary ventilation leading to respiratory failure and death. Surgery, in one form or another, is an ingredient of treatment. In its simplest form, surgery provides drainage of fluid (pleural effusion). Its most complex format is the operation known as extrapleural pneumonectomy within a chemoradiation protocol of a trimodality treatment,90 91 which has high mortality and morbidity but a better survival outcome. An alternative to extensive extrapleural pneumonectomy is the lung-sparing surgery of radical pleurectomy with adjuvant radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy with cytoreductive operation (decortication) added as local therapy.92 PDT in malignant pleural mesothelioma has been tried since the early 1990s and is still facing several challenges such as finding a suitable PS and an optimal method of illumination within the thoracic cavity and light dosimetry.93 Review of the literature indicates 13 clinical publications concerned with a total of 298 patients.94 The main PS used for malignant pleural mesothelioma is Photofrin (porfimer sodium). In recent years, radical pleurectomy combined with intracavitary Photofrin PDT has shown encouraging results.95

Brain Tumors

Brain tumors are rare, with an incidence of ∼6/100,000 persons, and are responsible for 3% of all cancer deaths.38 Without treatment, the survival averages < 40 weeks; with surgery and chemoradiation, there is improvement to about 52 weeks.96 PDT for brain tumors started in the1980s,97 and despite considerable preclinical and clinical research, many challenges remain due to the histologic differences and patterns of infiltration of neoplastic cells within the mass of normal cells; lack of a PS, which is endowed with specific ability to localize in the tumor; and lack of appropriate light and delivery devices suitable for brain tissue, which also match the absorption band of the specific PS.

Some of these issues are currently subject to investigation.98 99 100 101 102 Current clinical practice and research are focused on optimization of light and PS characteristics and dose parameters,101 102 use of PDT as an adjunct to surgery and/or radiotherapy to mop up residual tumor and treat recurrent lesions,103 use of PDT associated with/or in combination with surgery, and fluorescence diagnosis and fluorescence-guided surgery using the principle of PDR.104 105 106

Urologic Cancer

Prostate Cancer

Surgery, radiotherapy, and external beam radiotherapy or brachytherapy schedule, chemotherapy, and hormones are the standard primary treatments for prostate cancer. They are used individually, in concert, or in sequence depending on several factors including tumor characteristics, age, lifestyle, and patient choice.107 Patient participation in decision making is particularly important in prostate cancer, because some of the treatments may result in unwanted effects such as incontinence and erectile dysfunction not compatible with the patient's expectation of posttreatment quality of life. These factors are relevant in relation to the emergence of several focal therapy methods.107 108 109 PDT, as one of several focal therapies, has the distinct advantage in being cancer-specific and target-oriented. Many of the focal therapy methods rely on image guidance and operate on the basic principle of indiscriminate destruction of the image of the tumor and the visual impression of the lesion.110 Although PDT does need image-guided localization for illumination, it has an additional inherent guidance mechanism that is wavelength-specific to seek, find, and destroy the cancer. Some issues, however, have adversely affected the move from preclinical advances to the clinical practice of PDT for prostate cancer, namely appropriate PS, suitable light and its delivery device, and assessing the result of therapy. These require coordinated preclinical and clinical research.

At a clinical level, three types of PS have been explored and investigated in pilot and phase I and II trials: mTHPC/Foscan,111 112 motexafin lutetium,113 and vascular-targeted PS, TOOKAD.114 115 TOOKAD is currently the focus of attention and continuing clinical trials in several centers. Preliminary results are encouraging both in respect to localization of the PS in the prostate gland, its short administration–illumination interval, and the lack of skin photosensitivity reaction.

Bladder Cancer

The “niche” indication of PDT in bladder cancer is superficial transitional cell cancer (TCC) and carcinoma in situ (CIS) and began with the use of HPD in the 1980s.116 The use of Photofrin was then followed for patients with widespread refractory TCCs and CISs.117 118 With the availability of the ALA prodrug, the topical intravesical method was employed for whole (inner) bladder PDT in patients with widespread bladder TCC and CIS, thus avoiding the inconvenience of systemic photosensitization.119 The response rates for systemic and topical methods were similar, with 50 to 60% complete response for a duration of ∼3 years. In recent years, the diagnosis of TCC and CIS has been potentiated by the use of photodiagnosis using ALA- (or its derivatives) assisted fluorescence cystoscopy.120

League III

There are four cancers in this league: gynecologic cancers, breast cancer, cancer of the pancreas, and intraperitoneal cancers.

Gynecologic Cancers

Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia

Cervical cancer is the second most common cancer in women and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia is its precursor. The condition is directly related to some types of human papilloma virus infection; therefore, the assessment of any method of therapy should consider the effect on elimination of the virus as well. Standard therapies for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia are cold knife conization, loop electrosurgery, thermal laser, and cryotherapy. Short term, these treatments are satisfactory but have inconveniences such as pain, postoperative bleeding, and sequelae including stricture, cervical insufficiency, infertility, and difficulty of natural delivery. PDT has been used as an alternative treatment. Photofrin and topical ALA and its derivative hexaminolevulinate have been used successfully by several clinicians with favorable results.121 122 123 PDT results at short term are comparable with cold knife conization (91 and 100%, respectively). Similar results are obtained in relation to human papillomavirus clearance. However, PDT is not attended by the complications and the sequelae of conization and other standard treatments, and it can be repeated.

Vulvar Intraepithelial Neoplasia

Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia is a precancerous skin lesion of the vulva and is attended by symptoms of discomfort, local irritation, pruritus, and interference with sexual function. Standard treatments are thermal (CO2) laser and application of 5-fluouracil and/or imiquimod (imunoresponse modifier). The treatment of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia with PDT is currently being investigated, and topical ALA PDT is the most frequently used method. Improvement with relief of symptoms is reported in nearly 90% of patients,124 125 126 but recurrence rates are as high as 90%, which means repeat treatment will be required.124 After multiple sessions, ALA PDT can achieve long-term results lasting several months and years in some 60% of patients. Although other systemic PSs have been used in a small number of patients,127 the results are not consistent or sufficiently reproducible and there is the inconvenience of skin photosensitivity.

Ovarian Cancer

The standard treatment for many ovarian cancers is maximal cytoreductive surgery and chemotherapy. Fluorescence ALA visualization techniques (photodiagnosis) is helpful in the staging as well as in monitoring the effects of laparoscopic treatment.128 The method can also detect disseminated microfoci during surgery. The effectiveness of PDT with Photofrin and ALA in treating ovarian cancer has been evaluated in two studies.129 130 These were focused, however, more of the nature of feasibility rather than for evaluation of efficacy.

Breast Cancer

Despite a considerable amount of laboratory preclinical ex vivo and in vivo animal work, PDT in breast cancer has not moved to the clinical arena. The search for an appropriate PS, its matching light, and optimal methodology goes on. There are, nevertheless, some pilot studies on chest wall recurrence of breast cancer.131 132 133 134 In such cases, it is important to assess the extent of the lesion both in surface area and the depth of invasion. It is also necessary to take into account previous radiotherapy and make appropriate provision for the skin resurfacing of the area necrosed by PDT. The clinical work at this time is in the domain of experimentation and salvage.

Pancreatic Cancer

Some 20% of patients with adenocarcinoma, the main pancreatic cancer cell type, may be diagnosed at an early stage. Surgery has a potential 25 to 30% 5-year survival.135 The other 80% of patients have either metastases or locally advanced inoperable disease at presentation. Theoretically, PDT can debulk large locally advanced tumors and eradicate smaller ones. Most of the current knowledge is derived from laboratory and experimental in vivo animal work. A handful of patients treated within experimental protocols convey useful practical information. However, there are several challenges in applying PDT to pancreatic cancer. These include appropriate PS, light parameters, and method of access for illumination and the appropriate devices.

Considerable laboratory and preclinical studies are needed to align the required parameters. In two studies in a small number of patients, the PS was verteporfin and percutaneous computed tomography or endoscopic ultrasonography provided access for illumination.136 137

Intra-abdominal Photodynamic Therapy

The abdominal cavity accommodates many organs and structures, each of which can be the seat of a malignant tumor. The geometry of the abdominal cavity and its peritoneal lining is such that many neoplasms will be disseminated transcoelomically to other organs. Production of fluid (effusion) as exudate or transudate will also assist the malignant cell to navigate and disseminate through the abdominal cavity. In many such circumstances, PDT can theoretically assist surgery in the process of debulking as well as destruction of macro- and microfoci. Initial feasibility work has been performed in the 1990s.138 However, numerous issues require preclinical work, some of which are in progress at the present.

The tools of PDT for such a venture are the development of a PS with specific targeting capabilities and high ratio of localization in the tumor as compared with normal structures and the design of devices to uniformly distribute light to the outer layer of the organs without deep structural damage to healthy tissues. Recent developments in nanotechnology and advances in the manufacturing of optical fabrics are two areas that will assist progress in this domain.139 140 141 142

Morbidity and Mortality of Photodynamic Therapy

PDT-related mortality is extremely rare and usually follows an accidental overzealous illumination or lack of appreciation of the anatomical or pathologic area of the treated target. The morbidity of PDT should be considered for systemic and topical PDT separately.

Systemic PDT

The commonest unwanted effect of systemic PDT is the photosensitivity skin reaction, which in one review was reported to occur in 4 to 28% of cases.143 However, the rate is variable and depends on the type of PS, the experience of the PDT team, and the number of procedures undertaken by a team. Inflammation/ulceration at the site of IV administration due to extravasation of the PS is rare to nonexistent in expert hands. Hemorrhage in the case of infiltration by tumor of a blood vessel wall followed by PDT necrotic erosion is occasionally reported, which is more a matter of accident or miscalculated light dose. Perforation of a tubular structure or a body cavity due to overdosed illumination is also rare (less than 2%). Stricture of tubular organs due to scarring can occur in 6% of esophageal cases but usually yields with dilatation.

Complications in specific sites include hemorrhage in vascular lesions, respiratory complications in tracheobronchial PDT, and pain in upper gastrointestinal PDT.

Topical PDT

Pain is the commonest complication of topical PDT and is much more prominent when ALA is used in skin conditions affecting external genitalia (for example, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia). There are various ways to reduce the intensity of pain but in some extensive lesions, local or even general anesthetic may have to be considered. Ulceration, followed by scarring, can occur in some cases. Rarely, infection can occur in an ulcerating wound.

On the whole, most of the complications of PDT are avoidable and preventable. Complications in specific sites require the attention of an appropriate specialist related to the site.

Conclusion

The science of PDT has been around for over 100 years, and its clinical practice for cancer treatment has been in existence at least for 35 years. During the past 20 years, the science of PDT has taken a giant leap, far outstripping clinical application. It is unfortunate that PDT's clinical progress has not been as dramatic as its science. Much of the science of PDT in biology, photobiology, and chemistry departments of universities across the world is in fact a continuation of PDR, and it is unrealistic to consider that more than a few will ever reach clinical practice.

Clinical PDT initially began by following the footprints established through earlier laboratory and experimental work. Serious clinical studies in the 1980s were undertaken in common cancers, particularly those that most frequently occur, and in cases in which the illumination was technically easily performed. This fact is reflected in the current review, which places them in PDT league I. The methodology of PDT in all of the cancers in this league is well established and well tried and tested.

PDT in many of the cancers of leagues II and III is shown to be safe and effective in achieving its objective. However, the methodology and consistency of results require more work to increase their use.

What does PDT offer the surgeon?

PDT is a safe and effective cancer modality treatment whose technique can easily be mastered by a specialist surgeon.

In several cancers, PDT can be undertaken by endoscopic methods and is a routine undertaking for many surgeons. In the event of any complications, surgeons, by reason of training, are in a position to deal with the complications effectively.

In patients with precancerous lesions, where surgery might involve a prohibitively risky undertaking, PDT can be an option and achieve long-lasting clearance.

In patients with an early localized cancer, PDT can achieve long-term complete clearance amounting to a cure. Examples of these are presented throughout this review.

In patients with locally advanced disease with symptoms related to the volume of the tumor, PDT can be used for palliation and in some cases can confer a survival benefit.

PDT can be used together with other standard treatments including surgery.

Fluorescence imaging, which is part and parcel of PDR, can assist the surgeon to pick up residual tumor or to outline neoplastic infiltration at the margin of resection, thus ensuring a complete excision.

Based on this review and upon personal experience, we believe that future progress in clinical PDT must consider it within the multimodal cancer treatment methods and not as a monotherapy, which thus far has mostly been the case.

The medical profession has not been very welcoming in recent years in acknowledging the usefulness of PDT, partially because of financial constraints. By including PDT within a multimodality setting, we believe it will be easier to develop protocols of studies/clinical trials to the benefit of many cancer patients.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge the help and patience of Mrs. Janet Melvin in the production of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Raab O. Uber die Wirkung Fluorecierenden Stoffe auf Infusorien. Z Biol. 1904;30:524–546. [Google Scholar]

- 2.von Tappeiner H, Odlabauer J A. Uber die Wirkung der photodynamischen (fluorescierenden) Stoffe auf Protozoen und Enzyne. Dtsch Arch Klin Med. 1904;80:427–487. [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Tappeiner H, Jesionek H. Therapetische Versuche mit fluoreszierenden Stoffen. Munch Med Wochenschr. 1903;50:2042–2044. [Google Scholar]

- 4.von Tappeiner J H. Zur Behand lung der Hautcarcinome mit fluoreszierenden Stoffen. Dtsch Arch Klin Med. 1905;82:223–226. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moghissi K, Stringer M R, Dixon K. Fluorescence photodiagnosis in clinical practice. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2008;5(4):235–237. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krammer B, Malik Z, Pottier R, Stepp H. London, UK: RSC Publication; 2006. Principles of ALA-based FD; p. 51. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eljamel M S. Fluorescence image-guided surgery of brain tumors: explained step-by-step. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2008;5(4):260–263. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lipson R L, Baldes E J, Olsen A M. Hematoporphyrin derivative: a new aid for endoscopic detection of malignant disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1961;42:623–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lipson R L, Baldes E J, Gray M J. Hematoporphyrin derivative for detection and management of cancer. Cancer. 1967;20(12):2255–2257. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196712)20:12<2255::aid-cncr2820201229>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dougherty T J, Kaufman J E, Goldfarb A, Weishaupt K R, Boyle D, Mittleman A. Photoradiation therapy for the treatment of malignant tumors. Cancer Res. 1978;38(8):2628–2635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kessel D Dougherty T J eds. Porphyrin Photosensitisers New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1981 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kennedy J C, Pottier R H. Endogenous protoporphyrin IX, a clinically useful photosensitizer for photodynamic therapy. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1992;14(4):275–292. doi: 10.1016/1011-1344(92)85108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allison R R, Downie G H, Cuenca R, Hu X H, Childs C J, Sibata C H. Photosensitizers in clinical PDT. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2004;1(1):27–42. doi: 10.1016/S1572-1000(04)00007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mang T S. Lasers and light sources for PDT: past, present and future. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2004;1(1):43–48. doi: 10.1016/S1572-1000(04)00012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castano A P, Demidova T N, Hamblin M R. Mechanisms in photodynamic therapy: part two-cellular signaling, cell metabolism and modes of cell death. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2005;2(1):1–23. doi: 10.1016/S1572-1000(05)00030-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oleinick N L, Nieminen A L, Chiu S M. Norwood, MA: Artec House; 2008. Cell killing by photodynamic therapy; pp. 115–133. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allison R R, Moghissi K. Oncologic photodynamic therapy: clinical strategies that modulate mechanisms of action. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2013;10(4):331–341. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2013.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Firczuk M, Nowis D, Gołąb J. PDT-induced inflammatory and host responses. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2011;10(5):653–663. doi: 10.1039/c0pp00308e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garg A D, Nowis D, Golab J, Agostinis P. Photodynamic therapy: illuminating the road from cell death towards anti-tumour immunity. Apoptosis. 2010;15(9):1050–1071. doi: 10.1007/s10495-010-0479-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ethirajan M, Saenz C, Gupta A, Norwood, MA: Artec House; 2008. Photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy and imaging; pp. 13–39. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang Z. Photodynamic therapy in China: over 25 years of unique clinical experience. Part One—History and domestic photosensitizers. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2006;3(1):3–10. doi: 10.1016/S1572-1000(06)00009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandell J L, Zhu T C. A review of in-vivo optical properties of human tissues and its impact on PDT. J Biophotonics. 2011;4(11–12):773–787. doi: 10.1002/jbio.201100062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fodor L, Elman M, Ullmann Y. London, UK: Springer-Verlag Publishers; 2011. Light tissue interaction. In: Aesthetic Applications of Intense Pulsed Light. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fayter D, Corbett M, Heirs M, Fox D, Eastwood A. A systematic review of photodynamic therapy in the treatment of pre-cancerous skin conditions, Barrett's oesophagus and cancers of the biliary tract, brain, head and neck, lung, oesophagus and skin. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14(37):1–288. doi: 10.3310/hta14370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao F, Bai Y, Ma S R, Liu F, Li Z S. Systematic review: photodynamic therapy for unresectable cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2010;17(2):125–131. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0109-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang I, Bauer B, Andersson-Engels S, Svanberg S, Svanberg K. Photodynamic therapy utilising topical delta-aminolevulinic acid in non-melanoma skin malignancies of the eyelid and the periocular skin. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1999;77(2):182–188. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.1999.770213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loncaster J, Swindell R, Slevin F, Sheridan L, Allan D, Allan E. Efficacy of photodynamic therapy as a treatment for Gorlin syndrome-related basal cell carcinomas. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2009;21(6):502–508. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braathen L R, Szeimies R M, Basset-Seguin N. et al. Guidelines on the use of photodynamic therapy for nonmelanoma skin cancer: an international consensus. International Society for Photodynamic Therapy in Dermatology, 2005. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(1):125–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morton C Szeimies R M Sidoroff A et al. European Dermatology Forum Guidelines on topical photodynamic therapy Eur J Dermatol 2015; June 12 (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kennedy J C, Pottier R H, Pross D C. Photodynamic therapy with endogenous protoporphyrin IX: basic principles and present clinical experience. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1990;6(1–2):143–148. doi: 10.1016/1011-1344(90)85083-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piacquadio D J, Chen D M, Farber H F. et al. Photodynamic therapy with aminolevulinic acid topical solution and visible blue light in the treatment of multiple actinic keratoses of the face and scalp: investigator-blinded, phase 3, multicenter trials. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140(1):41–46. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morton C, Horn M, Leman J. et al. Comparison of topical methyl aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy with cryotherapy or fluorouracil for treatment of squamous cell carcinoma in situ: results of a multicenter randomized trial. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142(6):729–735. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.6.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morton C A, Whitehurst C, Moseley H, McColl J H, Moore J V, Mackie R M. Comparison of photodynamic therapy with cryotherapy in the treatment of Bowen's disease. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135(5):766–771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salim A, Leman J A, McColl J H, Chapman R, Morton C A. Randomized comparison of photodynamic therapy with topical 5-fluorouracil in Bowen's disease. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148(3):539–543. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Basset-Seguin N, Ibbotson S H, Emtestam L. et al. Topical methyl aminolaevulinate photodynamic therapy versus cryotherapy for superficial basal cell carcinoma: a 5 year randomized trial. Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18(5):547–553. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2008.0472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeitouni N C, Shieh S, Oseroff A R. Laser and photodynamic therapy in the management of cutaneous malignancies. Clin Dermatol. 2001;19(3):328–338. doi: 10.1016/s0738-081x(01)00170-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Szeimies R M, Ibbotson S, Murrell D F. et al. A clinical study comparing methyl aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy and surgery in small superficial basal cell carcinoma (8–20 mm), with a 12-month follow-up. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22(11):1302–1311. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jemal A, Bray F, Center M M, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keller G S, Doiron D R, Fischer G U. Photodynamic therapy in otorhinolaryngology-head and neck surgery. Arch Otolaryngol. 1985;111(11):758–761. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1985.00800130090012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Biel M A. Photodynamic therapy of head and neck cancers. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;635:281–293. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-697-9_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.von Beckerath M P, Reizenstein J A, Berner A L. et al. Outcome of primary treatment of early laryngeal malignancies using photodynamic therapy. Acta Otolaryngol. 2014;134(8):852–858. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2014.906748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ikeda H, Tobita T, Ohba S, Uehara M, Asahina I. Treatment outcome of Photofrin-based photodynamic therapy for T1 and T2 oral squamous cell carcinoma and dysplasia. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2013;10(3):229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Visscher S A, Melchers L J, Dijkstra P U. et al. mTHPC-mediated photodynamic therapy of early stage oral squamous cell carcinoma: a comparison to surgical treatment. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(9):3076–3082. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Biel M. Advances in photodynamic therapy for the treatment of head and neck cancers. Lasers Surg Med. 2006;38(5):349–355. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Allison R R, Sibata C, Gay H. PDT for cancers of the head and neck. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2009;6(1):1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Green B, Cobb A R, Hopper C. Photodynamic therapy in the management of lesions of the head and neck. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;51(4):283–287. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Graham E A, Singer J J. Successful removal of an entire lung for carcinoma of the bronchus. JAMA. 1933;101:13–17. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kato H, Konaka C, Ono J. et al. Preoperative laser photodynamic therapy in combination with operation in lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1985;90(3):420–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Okunaka T, Hiyoshi T, Furukawa K. et al. Lung cancers treated with photodynamic therapy and surgery. Diagn Ther Endosc. 1999;5(3):155–160. doi: 10.1155/DTE.5.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ross P Jr, Grecula J, Bekaii-Saab T, Villalona-Calero M, Otterson G, Magro C. Incorporation of photodynamic therapy as an induction modality in non-small cell lung cancer. Lasers Surg Med. 2006;38(10):881–889. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Akopov A, Rusanov A, Gerasin A, Kazakov N, Urtenova M, Chistyakov I. Preoperative endobronchial photodynamic therapy improves resectability in initially irresectable (inoperable) locally advanced non small cell lung cancer. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2014;11(3):259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.LoCicero J III, Metzdorff M, Almgren C. Photodynamic therapy in the palliation of late stage obstructing non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 1990;98(1):97–100. doi: 10.1378/chest.98.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weimann T J Diaz-Jimenez J P Moghissi K et al. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) with Photofrin is effective in the palliation of obstructive endobronchial lung cancer; results of two randomized trials (abstract) Paper presented at: Proceedings of the 34th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology; May 16–19, 1998; Los Angeles, CA

- 54.Ono R, Ikeda S, Suemasu K. Hematoporphyrin derivative photodynamic therapy in roentgenographically occult carcinoma of the tracheobronchial tree. Cancer. 1992;69(7):1696–1701. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920401)69:7<1696::aid-cncr2820690709>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Edell E S, Cortese D A. Photodynamic therapy in the management of early superficial squamous cell carcinoma as an alternative to surgical resection. Chest. 1992;102(5):1319–1322. doi: 10.1378/chest.102.5.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kato H. Photodynamic therapy for lung cancer—a review of 19 years' experience. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1998;42(2):96–99. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(97)00128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moghissi K, Dixon K, Thorpe J A, Stringer M, Oxtoby C. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) in early central lung cancer: a treatment option for patients ineligible for surgical resection. Thorax. 2007;62(5):391–395. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.061143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCaughan J S Jr, Williams T E. Photodynamic therapy for endobronchial malignant disease: a prospective fourteen-year study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1997;114(6):940–946, discussion 946–947. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(97)70008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moghissi K, Dixon K, Stringer M, Freeman T, Thorpe A, Brown S. The place of bronchoscopic photodynamic therapy in advanced unresectable lung cancer: experience of 100 cases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1999;15(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(98)00295-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lam S, Macaulay C, Leriche J C, Ikeda N, Palcic B. Early localization of bronchogenic carcinoma. Diagn Ther Endosc. 1994;1(2):75–78. doi: 10.1155/DTE.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Horvath T A, Hirano T, Horvathova M D. et al. Autofluorescence (safe) bronchoscopy and p21/ki-67 immunostaining related to carcinogenesis. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2004;1(1):13–22. doi: 10.1016/S1572-1000(04)00005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moghissi K, Dixon K, Stringer M R. Current indications and future perspective of fluorescence bronchoscopy: a review study. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2008;5(4):238–246. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Okunaka T, Kato H, Tsutsui H, Ishizumi T, Ichinose S, Kuroiwa Y. Photodynamic therapy for peripheral lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2004;43(1):77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2003.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moghissi K, Dixon K, Thorpe J A. A method for video-assisted thoracoscopic photodynamic therapy (VAT-PDT) Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2003;2(3):373–375. doi: 10.1016/S1569-9293(03)00073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.DeMeester T R, Attwood S E, Smyrk T C, Therkildsen D H, Hinder R A. Surgical therapy in Barrett's esophagus. Ann Surg. 1990;212(4):528–540, discussion 540–542. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199010000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moghissi K, Sharpe D A, Pender D. Adenocarcinoma and Barrett's oesophagus. A clinico-pathological study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1993;7(3):126–131. doi: 10.1016/1010-7940(93)90034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sujendran V, Sica G, Warren B, Maynard N. Oesophagectomy remains the gold standard for treatment of high-grade dysplasia in Barrett's oesophagus. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005;28(5):763–766. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Downs-Kelly E, Mendelin J E, Bennett A E. et al. Poor interobserver agreement in the distinction of high-grade dysplasia and adenocarcinoma in pretreatment Barrett's esophagus biopsies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(9):2333–2340, quiz 2341. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.El Hallani S, Guillaud M, Korbelik J, Marginean E C. Evaluation of quantitative digital pathology in the assessment of Barrett esophagus-associated dysplasia. Am J Clin Pathol. 2015;144(1):151–164. doi: 10.1309/AJCPK0Y1MMFSJDKU. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Overholt B F, Wang K K, Burdick J S. et al. Five-year efficacy and safety of photodynamic therapy with Photofrin in Barrett's high-grade dysplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66(3):460–468. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Oliphant Z, Snow A, Knight H, Barr H, Almond L M. Endoscopic resection with or without mucosal ablation of high grade dysplasia and early oesophageal adenocarcinoma—long term follow up from a regional UK centre. Int J Surg. 2014;12(11):1148–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thorpe J A, Moghissi K. Photofrin PDT for Barrett's oesophagus with high-grade dysplasia. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2008;5(1):36–37. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.American Cancer Society . Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2011. Global Cancer Facts & Figures. 2nd ed. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Moghissi K. Surgical resection for stage I cancer of the oesophagus and cardia. Br J Surg. 1992;79(9):935–937. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800790927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Berry M F, Zeyer-Brunner J, Castleberry A W. et al. Treatment modalities for T1N0 esophageal cancers: a comparative analysis of local therapy versus surgical resection. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8(6):796–802. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182897bf1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McCaughan J S Jr, Guy J T, Hawley P. et al. Hematoporphyrin-derivative and photoradiation therapy of malignant tumors. Lasers Surg Med. 1983;3(3):199–209. doi: 10.1002/lsm.1900030302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.McCaughan J S Jr Ellison E C Guy J T et al. Photodynamic therapy for esophageal malignancy: a prospective twelve-year study Ann Thorac Surg 19966241005–1009., discussion 1009–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Moghissi K, Dixon K, Thorpe J A, Stringer M, Moore P J. The role of photodynamic therapy (PDT) in inoperable oesophageal cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2000;17(2):95–100. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(99)00350-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Maier A, Tomaselli F, Gebhard F, Rehak P, Smolle J, Smolle-Jüttner F M. Palliation of advanced esophageal carcinoma by photodynamic therapy and irradiation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69(4):1006–1009. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)01440-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Moghissi K. Where does photodynamic therapy fit in the esophageal cancer treatment jigsaw puzzle? J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10 02:S52–S55. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sibille A, Lambert R, Souquet J C, Sabben G, Descos F. Long-term survival after photodynamic therapy for esophageal cancer. Gastroenterology. 1995;108(2):337–344. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Moghissi K, Dixon K, Stringer M, Thorpe J A. Photofrin PDT for early stage oesophageal cancer: long term results in 40 patients and literature review. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2009;6(3–4):159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2009.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nakeeb A Pitt H A Sohn T A et al. Cholangiocarcinoma. A spectrum of intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal tumors Ann Surg 19962244463–473., discussion 473–475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.McCaughan J S Jr, Mertens B F, Cho C, Barabash R D, Payton H W. Photodynamic therapy to treat tumors of the extrahepatic biliary ducts. A case report. Arch Surg. 1991;126(1):111–113. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1991.01410250119022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ortner M A, Liebetruth J, Schreiber S. et al. Photodynamic therapy of nonresectable cholangiocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 1998;114(3):536–542. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70537-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ortner M E, Caca K, Berr F. et al. Successful photodynamic therapy for nonresectable cholangiocarcinoma: a randomized prospective study. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(5):1355–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kahaleh M, Mishra R, Shami V M. et al. Unresectable cholangiocarcinoma: comparison of survival in biliary stenting alone versus stenting with photodynamic therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(3):290–297. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kniebühler G, Pongratz T, Betz C S. et al. Photodynamic therapy for cholangiocarcinoma using low dose mTHPC (Foscan(®)) Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2013;10(3):220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lu Y Liu L Wu J C et al. Efficacy and safety of photodynamic therapy for unresectable cholangiocarcinoma: a meta-analysis Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2015; June 9 (Epub ahead of print); doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2014.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sugarbaker D J, Wolf A S, Chirieac L R. et al. Clinical and pathological features of three-year survivors of malignant pleural mesothelioma following extrapleural pneumonectomy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;40(2):298–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sugarbaker D J, Richards W G, Bueno R. Extrapleural pneumonectomy in the treatment of epithelioid malignant pleural mesothelioma: novel prognostic implications of combined N1 and N2 nodal involvement based on experience in 529 patients. Ann Surg. 2014;260(4):577–580, discussion 580–582. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Friedberg J S. Photodynamic therapy for malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10 02:S75–S79. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Moghissi K, Dixon K. Photodynamic therapy in the management of malignant pleural mesothelioma: a review. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2005;2(2):135–147. doi: 10.1016/S1572-1000(05)00059-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Moghissi K Photodynamic therapy within global treatment of cancers for thoracic oncology Royal Society of Chemistry Publication. In press [Google Scholar]

- 95.Friedberg J S Culligan M J Mick R et al. Radical pleurectomy and intraoperative photodynamic therapy for malignant pleural mesothelioma Ann Thorac Surg 20129351658–1665., discussion 1665–1667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Eljamel M S. Boston, MA, and London, UK: Artech House; 2008. PDT for brain cancer; pp. 495–505. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Perria C, Capuzzo T, Cavagnaro G. et al. Fast attempts at the photodynamic treatment of human gliomas. J Neurosurg Sci. 1980;24(3–4):119–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kaye A H, Morstyn G, Brownbill D. Adjuvant high-dose photoradiation therapy in the treatment of cerebral glioma: a phase 1–2 study. J Neurosurg. 1987;67(4):500–505. doi: 10.3171/jns.1987.67.4.0500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Stylli S S, Kaye A H, MacGregor L, Howes M, Rajendra P. Photodynamic therapy of high grade glioma—long term survival. J Clin Neurosci. 2005;12(4):389–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Marks P V, Belchetz P E, Saxena A. et al. Effect of photodynamic therapy on recurrent pituitary adenomas: clinical phase I/II trial—an early report. Br J Neurosurg. 2000;14(4):317–325. doi: 10.1080/026886900417298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Eljamel M S. Photodynamic assisted surgical resection and treatment of malignant brain tumours technique, technology and clinical application. Photodiagn Photodyn Ther. 2004;1(1):93–98. doi: 10.1016/S1572-1000(04)00014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kostron H. Photodynamic diagnosis and therapy and the brain. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;635:261–280. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-697-9_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Muller P, Wilson B. Photodynamic therapy of brain tumours: postoperative “field fractionation”. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1991;9(1):117–119. doi: 10.1016/1011-1344(91)80009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Stummer W Pichlmeier U Meinel T Wiestler O D Zanella F Reulen H J; ALA-Glioma Study Group. Fluorescence-guided surgery with 5-aminolevulinic acid for resection of malignant glioma: a randomised controlled multicentre phase III trial Lancet Oncol 200675392–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Stummer W, Novotny A, Stepp H, Goetz C, Bise K, Reulen H J. Fluorescence-guided resection of glioblastoma multiforme by using 5-aminolevulinic acid-induced porphyrins: a prospective study in 52 consecutive patients. J Neurosurg. 2000;93(6):1003–1013. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.6.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Eljamel M S, Goodman C, Moseley H. ALA and Photofrin fluorescence-guided resection and repetitive PDT in glioblastoma multiforme: a single centre phase III randomised controlled trial. Lasers Med Sci. 2008;23(4):361–367. doi: 10.1007/s10103-007-0494-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Moore C M, Pendse D, Emberton M. Photodynamic therapy for prostate cancer—a review of current status and future promise. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2009;6(1):18–30. doi: 10.1038/ncpuro1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Eggener S E, Coleman J A. Focal treatment of prostate cancer with vascular-targeted photodynamic therapy. ScientificWorldJournal. 2008;8:963–973. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2008.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]