Significance

Unresolved endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress corresponds with various chronic diseases, such as hepatic steatosis and diabetes. Although cellular zinc deficiency has been implicated in causing ER stress, the effect of disturbed zinc homeostasis on hepatic ER stress and a role for zinc during stress are unclear. This study reveals that ER stress increases hepatic zinc accumulation via enhanced expression of metal transporter ZIP14. Unfolded protein response-activated transcription factors ATF4 and ATF6α regulate Zip14 expression in hepatocytes. During ER stress, ZIP14-mediated zinc transport is critical for preventing prolonged apoptotic cell death and steatosis, thus leading to hepatic cellular adaptation to ER stress. These results highlight the importance of normal zinc transport for adaptation to ER stress and to reduce disease risk.

Keywords: unfolded protein response, p-eIF2α/ATF4/CHOP pathway, apoptosis, steatosis, zinc metabolism

Abstract

Extensive endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress damages the liver, causing apoptosis and steatosis despite the activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR). Restriction of zinc from cells can induce ER stress, indicating that zinc is essential to maintain normal ER function. However, a role for zinc during hepatic ER stress is largely unknown despite important roles in metabolic disorders, including obesity and nonalcoholic liver disease. We have explored a role for the metal transporter ZIP14 during pharmacologically and high-fat diet–induced ER stress using Zip14−/− (KO) mice, which exhibit impaired hepatic zinc uptake. Here, we report that ZIP14-mediated hepatic zinc uptake is critical for adaptation to ER stress, preventing sustained apoptosis and steatosis. Impaired hepatic zinc uptake in Zip14 KO mice during ER stress coincides with greater expression of proapoptotic proteins. ER stress-induced Zip14 KO mice show greater levels of hepatic steatosis due to higher expression of genes involved in de novo fatty acid synthesis, which are suppressed in ER stress-induced WT mice. During ER stress, the UPR-activated transcription factors ATF4 and ATF6α transcriptionally up-regulate Zip14 expression. We propose ZIP14 mediates zinc transport into hepatocytes to inhibit protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) activity, which acts to suppress apoptosis and steatosis associated with hepatic ER stress. Zip14 KO mice showed greater hepatic PTP1B activity during ER stress. These results show the importance of zinc trafficking and functional ZIP14 transporter activity for adaptation to ER stress associated with chronic metabolic disorders.

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a cellular organelle where appropriate folding, assembly, and modification of proteins occur (1). Normal ER function can be compromised by pharmacological stimuli, such as tunicamycin (TM) or thapsigargin (2, 3), and by physiological stimuli, such as a high-fat diet (HFD), viral infection, oxidative stress, or chronic alcohol consumption (4–8). Perturbed ER function is collectively defined as ER stress. When ER stress occurs, mammalian cells activate the unfolded protein response (UPR), which comprises three discrete signaling pathways: the activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) branch, the inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1) branch, and the dsRNA-activated protein kinase R-like ER kinase (PERK) branch (9). These pathways act to relieve the protein burden of the ER by reducing translation through mRNA decay (10) and by enhancing protein-folding capacity through the expression of ER chaperones, including 78-kDa glucose-regulated protein (GRP78/BiP) and 94-kDa glucose-regulated protein (GRP94) (11). Cells survive if ER function is recovered through the activation of these adaptation pathways. However, if components of the UPR are compromised or ER stress is too severe, the UPR leads cells to apoptotic cell death via PERK-mediated phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) (12). Phosphorylated eIF2α (p-eIF2α) selectively enhances translation of activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) mRNA, which leads to up-regulation of C/EBP-homologous protein (CHOP), a transcription factor that induces expression of apoptosis-associated components. Thus, enhanced activation of the p-eIF2α/ATF4/CHOP pathway is a hallmark of maladaptation against ER stress. Sustained apoptosis from ER stress influences numerous pathological conditions, including diabetes and obesity (8, 13). In the liver, apoptosis disrupts homeostasis of lipid regulation, causing hepatic steatosis (14).

Zinc is an essential mineral required for normal cellular functions playing catalytic, structural, and regulatory roles (15). To maintain zinc homeostasis, mammalian cells use 24 known zinc transporters that tightly control the trafficking of zinc in and out of cells and subcellular organelles. These transporters are within two families: ZnT (Zinc Transporter; SLC30) and ZIP (Zrt-, Irt-like protein; SLC39) (16–18). Physiological stimuli have been shown to regulate the expression and function of some of these transporters. Ablation of some of these transporters results in zinc dyshomeostasis and metabolic defects. Ablation of Zip14 (Slc39a14) in mice leads to a phenotype that includes endotoxemia, hyperinsulinemia, increased body fat, and impaired hepatic insulin receptor trafficking (19–21). Zinc and zinc transporters have been implicated in ER stress and the UPR. Zinc deficiency may induce or exacerbate ER stress and apoptosis. In yeast and some mammalian cells, the UPR was activated by zinc restriction (22, 23). A rat model of alcoholic liver disease created by zinc deficiency was shown to trigger ER stress-induced apoptosis (24). We reported that consumption of a zinc-deficient diet by mice exacerbated ER stress-induced apoptosis and hepatic steatosis during TM-induced ER stress (25). Those recent studies showed that zinc can modulate the proapoptotic p-eIF2α/ATF4/CHOP pathway during ER stress. A number of zinc transporters have also been associated with ER stress and the UPR. Administration of TM altered expression of numerous zinc transporter genes in mouse liver, including ZnT3, ZnT5, ZnT7, Zip13, and Zip14 (23). In other vertebrate cells, knockdown (KD) of ZnT3, ZnT5, ZnT7, and Zip13 induced or potentiated ER stress (26–28). The role for ZIP14 in ER stress has not been defined.

In the present study, we explored a role of ZIP14 during pharmacologically, HFD-induced ER stress using a Zip14−/− (KO) mouse model, which exhibits impaired hepatic zinc uptake. We report that during UPR activation, ATF4 and ATF6α transcriptionally regulate Zip14 expression and that ZIP14-mediated hepatic zinc accumulation is critical for adaptation to ER stress by preventing sustained apoptosis and steatosis. We propose that ZIP14-mediated zinc transport suppresses protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) activity, which may contribute to overcoming ER stress.

Results

TM Administration Alters Hepatic Zinc Homeostasis and Zinc Transporter Expression, Particularly ZIP14.

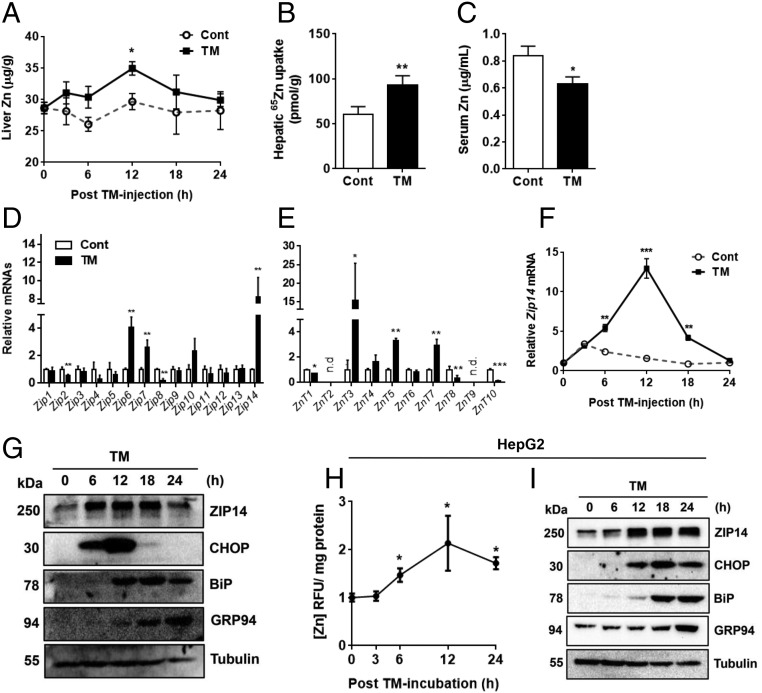

First, to define the effect of ER stress on zinc homeostasis, TM, a potent ER stress inducer, was injected i.p. into mice to induce systemic ER stress. TM is a compound that blocks N-glycosylation of newly synthesized protein. As measured by atomic absorption spectrophotometry, TM-injected mice showed significantly higher hepatic zinc concentrations, along with hypozincemia, compared with vehicle-injected mice (Fig. 1 A and C). At 12 h after administration, liver zinc concentrations of the TM group were ∼15% higher than liver zinc concentrations of the control group. Administration of 65Zn by gavage confirmed markedly increased zinc uptake by the liver after administration of TM (∼1.6-fold) (Fig. 1B). No difference in zinc uptake was observed 12 h after administration of TM in tissues that are known to be highly affected by ER stress: the pancreas, kidney, and white adipose tissue (Fig. S1 B–D; WT). Therefore, the liver was our focus of further experiments. Because zinc homeostasis is maintained by zinc transporter activity, we examined expression of 24 known zinc transporter genes in the liver. The primer/probe sequences of genes are provided in Table S1. Among ZIP family transporters, Zip14 expression was most highly up-regulated by TM (∼8.2-fold) (Fig. 1D). Among ZnT family transporters, ZnT3 mRNA expression was markedly increased after administration of TM (∼15-fold) (Fig. 1E). However, ZnT3 has a low hepatic abundance (16), and was not further evaluated. ZIP14 mRNA and protein peaked at 12 h after administration of TM (Fig. 1 F and G), which coincided with maximum zinc accumulation (Fig. 1A). The increased hepatic zinc concentration and ZIP14 expression were also observed in mice injected with another ER stress inducer, thapsigargin, an inhibitor of ER Ca2+-ATPase (Fig. S2 A and B). Because liver tissue is composed of multiple cell types, we used human hepatoma HepG2 cells to support the in vivo studies. To measure total cellular zinc level in HepG2 hepatocytes, cell lysates were incubated with the zinc fluorophore FluoZin3-AM. Intensity of fluorescence represents the total cellular labile zinc concentration. Consistent with data from the liver of TM-treated mice, TM treatment significantly increased fluorescence (∼2.1-fold after 12 h) (Fig. 1H), which coincided with increased ZIP14 expression (Fig. 1I).

Fig. 1.

TM-mediated ER stress increases hepatic zinc uptake and ZIP14. Hepatic Zn concentration (A) and 65Zn uptake (B) in mice (n = 3–4) are shown after administration of TM (2 mg/kg) or vehicle. (C) Serum Zn concentration in mice (n = 3–4) 18 h after administration of TM (2 mg/kg) or vehicle. Relative expression of members of the ZIP family (D) and ZnT family transporter (E) genes in the liver of mice (n = 3–4) are shown after administration of TM (2 mg/kg) or vehicle for 12 h. Time-dependent expression of Zip14 mRNA (n = 3–4) (F) and immunoblot analysis of ZIP14 and markers of ER stress (G) in liver lysates (n = 3–4, pooled samples) are shown after administration of TM or vehicle for the indicated times. (H) Total cellular Zn concentrations in HepG2 cells were determined by measurement of fluorescence after incubation with FluoZin3-AM (5 μM) following treatment with TM (1 μg/mL) or vehicle (n = 5). RFU, relative fluorescent unit. (I) Immunoblot analysis of ZIP14 and markers of ER stress in lysates of HepG2 cells after TM (1 μg/mL) or vehicle treatment. All data are represented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Cont, control.

Fig. S1.

Measurement of 65Zn uptake in plasma (A), pancreas (B), kidney (C), and white adipose tissue (WAT) (D) of WT and Zip14 KO mice (n = 3–4) is shown 12 h after administration of TM (2 mg/kg) or vehicle. Concentration of nonheme iron (E) and manganese (F) in livers of WT and Zip14 KO mice (n = 3–4) is shown 12 h after administration of TM (2 mg/kg) or vehicle. All data are represented as mean ± SD. Labeled means without a common letter differ significantly (P < 0.05). Cont, control.

Table S1.

List of primers and probes used for qPCR analysis

| Gene | Sense | Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

| Mouse | ||

| Grp78 | Forward | TTCTGCCATGGTTCTCACTAAA |

| Grp78 | Reverse | TTGTCGCTGGGCATCATT |

| Grp78 | Probe | AGACTGCTGAGGCGTATTTGGGAA |

| Chop | Forward | CAGCGACAGAGCCAGAATAA |

| Chop | Reverse | CAGGTGTGGTGGTGTATGAA |

| Chop | Probe | TGAGGAGAGAGTGTTCCAGAAGGAAGT |

| Chrebp | Forward | CTGGGGACCTAAACAGGAGC |

| Chrebp | Reverse | GAAGCCACCCTATAGCTCCC |

| Acc | Forward | TGACAGACTGATCGCAGAGAAAG |

| Acc | Reverse | TGGAGAGCCCCACACACA |

| Scd1 | Forward | CCGGAGACCCCTTAGATCGA |

| Scd1 | Reverse | TAGCCTGTAAAAGATTTCTGCAAACC |

| Cd36 | Forward | TGGAGCTGTTATTGGTGCAG |

| Cd36 | Reverse | TGGGTTTTGCACATCAAAGA |

| Fabp | Forward | GCTGCGGCTGCTGTATGA |

| Fabp | Reverse | CACCGGCCTTCTCCATGA |

| Pparα | Forward | CTGCAGAGCAACCATCCAGAT |

| Pparα | Reverse | GCCGAAGGTCCACCATTTT |

| Cpt1α | Forward | TGGCATCATCACTGGTGTGTT |

| Cpt1α | Reverse | GTCTAGGGTCCGATTGATCTTTG |

| Acox1 | Forward | GCCCAACTGTGACTTCCATC |

| Acox1 | Reverse | GCCAGGACTATCGCATGATT |

| Apoe | Forward | GCTGGGTGCAGACGCTTT |

| Apoe | Reverse | TGCCGTCAGTTCTTGTGTGACT |

| Apob | Forward | CGTGGGCTCCAGCATTCTA |

| Apob | Reverse | TCACCAGTCATTTCTGCCTTTG |

| Human | ||

| Zip14 (hnRNA) | Forward | TCCAAGTCTGCAGTGGTGTT |

| Zip14 (hnRNA) | Reverse | ACAATTGGGCCTCACCCAT |

| Zip14 (ChIP) | Forward | TTCCGGAGGCAGGAGGA |

| Zip14 (ChIP) | Reverse | CAGCTTAGCCGGTGCGT |

Fig. S2.

(A) Hepatic Zn concentration in mice (n = 3) 6 h after administration of thapsigargin (TG; 1 mg/kg) or vehicle. (B) Immunoblot analysis of ZIP14 and BiP in liver lysates (n = 3) 6 h after administration of TG (1 mg/kg) or vehicle. All data are represented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05.

Zip14 KO Mice Display Impaired Hepatic Zinc Uptake and Higher Apoptosis During TM-Induced ER Stress.

Next, we examined a potential role of ZIP14 during ER stress because increased hepatic ZIP14 expression and zinc accumulation after TM coincided with a marked reduction of CHOP expression (Fig. 1G). To test the hypothesis that ZIP14-mediated zinc uptake is critical to suppress apoptosis, we used conventional Zip14−/− (KO) mice (Fig. 2A). During steady-state conditions, the liver of Zip14 KO mice did not show any indices of UPR activation (Fig. S3). Following TM, Zip14 KO mice exhibited less significant change in hepatic zinc uptake, whereas WT mice displayed significant zinc accumulation (Fig. 2B). Measurement of radioactivity after 65Zn administration by gavage also showed impaired zinc uptake in Zip14 KO mice during ER stress (Fig. 2C). Expression of UPR pathway components, including proapoptotic pathway proteins (p-eIF2α, ATF4, and CHOP) and adaptation pathway proteins (BiP and GRP94), was examined. WT mice showed a marked reduction of proapoptotic protein expression 24 h after administration of TM, whereas Zip14 KO mice displayed sustained expression (Fig. 2D). TUNEL assays of liver sections showed a significantly greater number of TUNEL-positive cells in Zip14 KO mice (∼2.3-fold), indicating that the KO mice had a greater level of apoptosis after TM administration (Fig. 2E). Serum alanine aminotransferase activity, a common marker for liver damage, was also greater in Zip14 KO mice after administration of TM (∼2.5-fold) (Fig. 2F). Furthermore, Zip14 KO mice expressed significantly less GRP94 than WT mice (∼0.6-fold) (Fig. 2D), which may indicate an impaired protein folding function.

Fig. 2.

ZIP14 KO mice show greater ER stress-induced apoptosis. (A) Immunoblot analysis of ZIP14 from liver lysates of WT and Zip14−/− (KO) mice 12 h after administration of TM (2 mg/kg) or vehicle. Hepatic Zn concentration (B) and 65Zn uptake (C) in WT and Zip14 KO mice (n = 3–4) are shown after administration of TM (2 mg/kg) or vehicle. (D) Immunoblot analysis of ER stress markers from liver lysates of WT and Zip14 KO mice (n = 3–4, pooled samples) after administration of TM (2 mg/kg). Individual blots (24 h after TM, n = 4) were quantified using digital densitometry to determine relative protein abundance. (E) Representative images of TUNEL assays of liver sections of WT and Zip14 KO mice 24 h after administration of TM (2 mg/kg) or vehicle. TUNEL-positive cells in fields were quantified. (Magnification: 40×.) (Scale bars: 25 μm.) (F) Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activity of WT and Zip14 KO mice 24 h after administration of TM (2 mg/kg) or vehicle (n = 3–4). n.d., not detected. All data are represented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05. Labeled means without a common letter differ significantly (P < 0.05).

Fig. S3.

(A) Relative expression of BiP and Chop in livers of WT and Zip14 KO mice (n = 3). (B) Immunoblot analysis of ZIP14 and ER stress markers in liver lysates of WT and Zip14 KO mice (n = 3). All data are represented as mean ± SD.

To test if there is a direct effect of zinc in the HepG2 hepatocytes, we knocked down Zip14 with siRNA and then supplemented zinc acetate along with pyrithione, a zinc ionophore. Pyrithione was added to improve zinc access under Zip14 KD conditions. The efficiency of Zip14 KD using siRNA transfection was ∼90% (Fig. S4A). TM-treated Zip14 KD cells showed an ∼24% lower cellular zinc level compared with TM-treated control cells, as measured by FluoZin3-AM (Fig. 3A, first four bars). To establish an optimal level of zinc supplementation, we treated cells with zinc acetate, ranging from 2.5 to 20 μM. A maximal level of cellular zinc was obtained with TM-treated Zip14 KD cells when 5 μM zinc acetate was added along with pyrithione (Fig. 3A). Thus, 5 μM zinc acetate was used subsequently to test the effects of zinc supplementation. Higher expression of ATF4 (∼2.6-fold) and CHOP (∼1.8-fold) and lower expression of GRP94 (∼0.4-fold) were observed in Zip14 KD cells after TM treatment (Fig. 3B, lanes 3 and 4). In response to TM, zinc-supplemented Zip14 KD cells expressed markedly reduced ATF4 (∼34%) and CHOP (∼50%) proteins compared with non–zinc-supplemented Zip14 KD cells (Fig. 3B, lanes 4 and 6). In addition, expression of GRP94 was increased (∼1.6-fold) after zinc supplementation of the cells. TM treatment increased p-eIF2α expression, which was reduced after zinc supplementation in Zip14 KD cells (Fig. 3B). The lower cell viability shown in TM-treated Zip14 KD cells (Fig. 3C) was eliminated by zinc supplementation (Fig. 3D).

Fig. S4.

Relative expression of Zip14 (A), Atf4 (B), and Atf6α (C) mRNAs in HepG2 hepatocytes transfected with the indicated siRNAs. Csi, control siRNA.

Fig. 3.

Supplementation with zinc rescues ER stress-induced apoptosis in Zip14 KD hepatocytes. (A) Total cellular Zn concentrations were determined by measurement of fluorescence after incubation with FluoZin3-AM (5 μM). HepG2 cells were treated with the indicated dose of zinc acetate and/or pyrithione (50 μM) for 30 min, which was followed by TM (1 μg/mL) or vehicle treatment for 12 h. (B) Immunoblot analysis of ZIP14 and ER stress markers from cell lysates. Zip14 siRNA-transfected or control siRNA-transfected HepG2 cells were incubated for 30 min with zinc acetate (5 μM) and pyrithione (50 μM), which was followed by a 24-h incubation with TM (1 μg/mL) or vehicle. Individual blots (lanes 3–6, n = 3) were quantified using digital densitometry to determine relative protein abundance. (C and D) Cell viability was measured using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay. (C) Zip14 siRNA-transfected or control siRNA-transfected HepG2 cells were treated with TM (1 μg/mL) for 1 d or 2 d. (D) Cells were pretreated with zinc acetate (5 μM) and pyrithione (50 μM) for 30 min before TM (1 μg/mL) treatment for 18 h. All data are represented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05. Labeled means without a common letter differ significantly (P < 0.05). Csi, control siRNA.

Zip14 KO Mice Show a Greater Level of Hepatic Steatosis During TM-Induced ER Stress.

Prolonged ER stress in the liver has been linked to the occurrence of hepatic steatosis. Greater levels of lipid droplet accumulation in Zip14 KO mice were observed with H&E staining of the liver sections after administration of TM (∼1.9-fold) (Fig. 4A). Quantification of triglyceride (TG) accumulation in the liver supported this observation (Fig. 4B). Because hepatic lipid homeostasis is mainly maintained by four mechanisms, namely, de novo fatty acid (FA) synthesis, FA oxidation, FA uptake into the liver, and lipoprotein secretion, we measured expression of genes involved in these pathways in the Zip14 KO mice to elucidate which mechanism(s) led to severe steatosis. With TM administration, genes involved in de novo FA synthesis, such as Srebp1c, Acc, Fasn, and Scd1, were significantly suppressed in WT mice by ∼60%, ∼85%, and ∼74%, respectively (Fig. 4C). In contrast, expression of Srebp1c, Acc, Fasn, and Scd1 in TM-treated Zip14 KO mice was ∼2.5-fold, ∼2.2-fold, ∼3.2-fold, and ∼fourfold greater, respectively, than in TM-treated WT mice, indicating that FA synthesis in Zip14 KO mice was enhanced during the stress. In the same setting, there were no significant differences in expression of genes involved in FA oxidation, FA uptake, and lipoprotein secretion (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

Zip14 KO mice exhibit a greater level of hepatic TG accumulation after TM-induced ER stress. (A) Representative images of H&E-stained liver sections of WT and Zip14 KO mice 24 h after administration of TM (2 mg/kg) or vehicle. The lipid droplet area in the field was measured. (Magnification: 10×.) (Scale bars: 100 μm.) (B) Liver TG levels of WT and Zip14 KO mice were measured 24 h after administration of TM (2 mg/kg) or vehicle (n = 3–4). Relative expression of genes that regulate FA synthesis (C) and FA β-oxidation, FA uptake, and lipoprotein secretion (D) were measured in livers of WT and Zip14 KO mice 12 h after administration of TM (2 mg/kg) or vehicle (n = 3–4). All data are represented as mean ± SD. Labeled means without a common letter differ significantly (P < 0.05).

HFD-Mediated ER Stress Is Exacerbated in Zip14 KO Mice.

Feeding an HFD has been used to trigger ER stress in rodents and provides a model with high physiological relevance (8). Thus, we analyzed indices of ER stress after feeding mice with an HFD (60 kcal% fat) or chow diet (12 kcal% fat). After 16 wk, body weights of HFD-fed mice increased 10.2 ± 2.6 g, whereas chow-fed mice gained 2.8 ± 0.2 g. Both genotypes gained weight at the same rate during HFD feeding. WT mice showed enhanced ZIP14 expression after the HFD (Fig. 5 A and B). Hepatic zinc concentrations in HFD-fed WT mice were ∼17% higher compared with chow-fed WT mice, indicating that an HFD increases zinc uptake (Fig. 5C). However, zinc levels in HFD-fed Zip14 KO mice were unchanged, indicating that ZIP14 facilitates hepatic zinc accumulation. Although Zip9 mRNA expression was also increased by the HFD (Fig. 5A), its hepatic abundance is known to be low (16); thus, it is unlikely that ZIP9 contributes markedly to hepatic zinc uptake. This conclusion is also supported by showing that hepatic zinc does not increase due to HFD consumption in Zip14 KO mice (Fig. 5C). Both genotypes showed elevated expression of UPR components, including p-eIF2α, ATF4, CHOP, BiP, and GPR94, indicating UPR activation in response to the HFD (Fig. 5D). However, HFD-fed Zip14 KO mice expressed greater levels of proapoptotic signatures, including p-eIF2α, ATF4, and CHOP, compared with HFD-fed WT mice, indicating that ablation of Zip14 worsens ER stress-associated apoptosis in this setting. Expression of ATF4 and CHOP was ∼3.7-fold and ∼3.2-fold greater, respectively, in Zip14 KO mice. Of particular note is the similarity of these results to the results attained with TM-induced ER stress. Specifically, the HFD-fed Zip14 KO mice expressed a lower level of GRP94 than HFD-fed WT mice (∼0.6-fold). Hepatic TG accumulation after the HFD tended to be higher in Zip14 KO mice (Fig. 5E). Moreover, this observation coincided with significantly higher mRNA expression of Srebp1c (∼1.7-fold), Fasn (∼1.8-fold), and Scd1 (∼1.9-fold) (Fig. 5F), suggesting a greater level of FA synthesis led to more hepatic TG accumulation in the Zip14 KO mice.

Fig. 5.

HFD-fed Zip14 KO mice show greater hepatic ER stress-induced apoptosis and TG accumulation. Mice were fed the HFD or a chow diet for 16 wk. (A) Relative gene expression of members of the ZIP family transporter in WT mice (n = 4). (B) Immunoblot analysis of ZIP14 from liver lysates of WT and KO mice. (C) Hepatic Zn concentration of WT and Zip14 KO mice (n = 4). (D) Immunoblot analysis of ER stress markers from liver lysates of WT and KO mice (n = 4, pooled samples used). Individual blots (HFD, n = 4) were quantified using digital densitometry to determine relative protein abundance. (E) Liver TG levels were quantified in WT and Zip14 KO mice (n = 4). (F) Relative expression of genes that regulate FA synthesis were measured in livers of WT and Zip14 KO mice (n = 4). All data are represented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05. Labeled means without a common letter differ significantly (P < 0.05).

Increased PTP1B Activity Is Observed in Zip14 KO Mice During ER Stress.

As a possible mechanism underlying the increased ER stress in Zip14 KO mice, we focused on PTP1B, an enzyme that has been implicated in ER stress. PTP1B expression was increased in ER stress induced by TM and the HFD, and deletion of the protein in vivo and in vitro significantly reduced ER stress-associated apoptosis and steatosis (29–31). Because zinc is a known inhibitor of PTP1B activity (32, 33), we hypothesized that Zip14 KO would exhibit increased PTP1B activity during ER stress due to impaired zinc uptake, and thus disrupt adaptation to ER stress. Consistent with previous reports (30, 31), expression of proapoptotic proteins was significantly decreased in TM-treated Ptp1b KD cells compared with TM-treated control cells (Fig. 6A). ATF4 and CHOP expression was reduced by ∼42% and ∼30%, respectively, in the Ptp1b KD condition. This finding was supported by markedly higher cell viability in Ptp1b KD cells after TM challenge (Fig. 6B). At steady state, Zip14 KO mice expressed less PTP1B protein than WT mice (∼0.6-fold), but PTP1B activity was comparable (Fig. 6 C and D). Following TM administration, hepatic PTP1B expression was increased in both genotypes (Fig. 6C, TM). However, PTP1B activity was significantly greater in Zip14 KO mouse liver (∼1.7-fold) (Fig. 6D). The same pattern was observed in HFD-fed mice. PTP1B activity was significantly greater in the liver of Zip14 KO mice compared with WT mice (∼1.5-fold), although the amount of protein expression was not different (Fig. 6 E and F). In HepG2 hepatocytes, Zip14 siRNA KD did not alter PTP1B protein levels (Fig. 6G). In contrast, PTP1B activity was increased in the hepatocytes following Zip14 siRNA KD and TM treatment, but it was significantly reduced with zinc supplementation (Fig. 6H). These data demonstrate a direct effect of zinc on PTP1B activity in this setting. Collectively, these data suggest that normal hepatocytes suppress PTP1B activity during ER stress by regulating cellular zinc availability via ZIP14 induction. Impaired zinc uptake in the KO mice or by siRNA KD disturbs these events. A model underlying ZIP14-mediated adaptation and defense against ER stress is presented in Fig. 6I.

Fig. 6.

ZIP14 is required to suppress hepatic PTP1B activity after TM administration and the HFD. Immunoblot analysis of PTP1B and ER stress markers (A) and measurement of cell viability using the MTT assay (B) in HepG2 hepatocytes transfected with Ptp1b siRNA or control siRNA are shown. Cells were treated with TM (1 μg/mL) or vehicle for 24 h. In A, individual blots (TM, n = 3) were quantified using digital densitometry to determine relative protein abundance. Immunoblot analysis of PTP1B protein (C) and measurement of PTP1B activity (D) in livers of WT and Zip14 KO mice are shown 12 h after administration of TM (2 mg/kg) or vehicle (n = 3–4, pooled samples used for C). Analysis of PTP1B protein (E) and measurement of PTP1B activity (F) in livers of WT and Zip14 KO mice fed with HFD or chow for 16 wk (n = 4, pooled samples used for E) are shown. Immunoblot analysis of PTP1B protein (G) and measurement of PTP1B activity (H) in HepG2 hepatocytes transfected with Zip14 siRNA or control siRNA are shown. Cells were pretreated with zinc acetate (5 μM) and pyrithione (50 μM) for 30 min before TM (1 μg/mL) treatment for 12 h. (I) Proposed model for ZIP14-mediated zinc transport and inhibition of PTP1B activity. All data are represented as mean ± SD. Labeled means without a common letter differ significantly (P < 0.05).

Zip14 Is Transcriptionally Regulated by ATF4 and ATF6α During TM Treatment.

Because we observed an induction of Zip14 during TM- and HFD-induced ER stress, our next focus was to identify transcription factor(s) that regulate Zip14. For efficient gene manipulation, we performed in vitro experiments using HepG2 hepatocytes. During TM treatment, Zip14 mRNA was increased in a dose-dependent manner, and treatment with actinomycin D, a transcription inhibitor, suppressed induction, indicating that Zip14 induction by TM is regulated at the transcriptional level (Fig. 7A). Transcriptional regulation was supported by the time-dependent increases in Zip14 mRNA and heterogeneous nuclear RNA. Both exhibited similar expression patterns following TM treatment (Fig. 7B). Global gene expression screening data provided clues regarding the potential Zip14-regulating transcription factors ATF4 and ATF6α (34, 35). ATF4 and ATF6α have been shown to have a strong binding affinity to the cAMP-response element (CRE) sequence [TGACGT(C/A)(G/A)] (Fig. 7C). Matinspector software analysis revealed that the Zip14 promoter has a potential binding site for both ATF4 and ATF6α at −94 to −89, which matches with a core motif of CRE, and was conserved in mice and humans (Fig. 7D). To test the expression of Zip14 under ATF4-KD or ATF6α-KD conditions, HepG2 hepatocytes were transfected with either Atf4 or Atf6α siRNA (Fig. S4 B and C). KD of Atf4 resulted in significantly reduced Zip14 induction at both 6 h and 24 h after TM treatment (Fig. 7E), whereas KD of Atf6α reduced induction only at 24 h after TM treatment (Fig. 7G). To ensure actual binding of transcription factors to the potential binding site of the Zip14 promoter, we conducted ChIP-PCR. Detection of DNA enrichment revealed high ATF4 DNA binding 6 h after TM treatment. Binding was reduced thereafter (Fig. 7F). However, enhanced binding of ATF6α was only detected 24 h after TM treatment (Fig. 7H). Western blotting showed that ATF4 expression was induced until 12 h after TM treatment, and was then decreased at 24 h (Fig. 7I). This finding suggests a time-dependent regulation by ATF4 and ATF6α in which ATF4 first binds to the Zip14 promoter due to increased expression and higher binding affinity and ATF6α then binds to the promoter after ATF4 expression is decreased.

Fig. 7.

Zip14 is transcriptionally regulated by ATF4 and ATF6α in a time-dependent manner during TM treatment. (A) Relative expression of Zip14 mRNA in HepG2 cells treated with TM (1 μg/mL) and/or actinomycin D (Act D; 2 μg/mL) for 12 h. (B) Relative expression of Zip14 mRNA and heterogeneous nuclear RNA (hnRNA) in HepG2 cells treated with TM (1 μg/mL) or vehicle. (C) Consensus motif of CRE and binding motifs of ATF4 and ATF6. (D) Sequence of mouse and human Zip14 promoter regions (from −120 to +1). Identical nucleotides are indicated by an asterisk. The TGACG sequence (from −94 to −89) is marked by a box. Relative expression of Zip14 mRNA in TM-treated HepG2 cells (1 μg/mL) after transfection with control siRNA, Atf4 siRNA (E), or Atf6α siRNA (G) is shown. Enrichment of DNA bound to ATF4 antibody (F) or ATF6α antibody (H) was measured by quantitative real-time PCR after ChIP assays in TM-treated HepG2 cells (1 μg/mL). Nonspecific rabbit IgG antibody was used as a negative control. (I) Immunoblot analysis of ATF4 and full-length and cleaved ATF6α in TM-treated HepG2 cells (1 μg/mL). All data are represented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Discussion

In this report, we demonstrate that TM- and HFD-induced ER stress triggers ZIP14-mediated zinc accumulation in mouse liver. Both routes to ER stress yield remarkably comparable results (Figs. 2 and 5). This event is critical for adaptation to ER stress by preventing prolonged apoptosis and steatosis, possibly via inhibition of PTP1B activity. During TM-induced ER stress, Zip14 up-regulation in HepG2 hepatocytes is modulated at the transcriptional level by the UPR-activated transcription factors ATF4 and ATF6α. These findings are summarized in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Role of ZIP14-mediated zinc transport in ER stress adaptation. Based on the data in this report, we propose a cycle where ER stress sequentially increases expression of ATF4 and ATF6α. The transcription factors increase transcription of Zip14, leading to increased ZIP14 in hepatocytes. Enhanced transporter activity increases intracellular zinc concentration, leading to inhibition of PTP1B activity.

During ER stress, cellular metabolism is largely altered by activation of UPR pathways in an effort to restore ER homeostasis. This activation includes enhancing expression of proteins that help the ER folding function, such as ER chaperones, and reducing translation of mRNA to reduce cellular protein burden (11). Several lines of evidence indicate that ER stress also alters the metabolism of some metals. For example, mice injected with TM have been shown to exhibit hypoferremia and iron sequestration in the spleen and liver (36). Regarding zinc metabolism and ER stress adaptation, it has been shown recently in mice that TM administration alters hepatic gene expression of multiple zinc transporters (23). That observation is supported by our present study, in which ZIP14-mediated hepatic zinc uptake was observed, along with hypozincemia, after TM and thapsigargin treatments (Fig. 1 A–C and Fig. S2A), demonstrating that acute ER stress induction alters zinc metabolism. We focused on the liver because no difference in zinc uptake was observed in the pancreas, kidney or white adipose tissue, which are known to be highly affected by ER stress (Fig. S1 B–D).

We also examined ER stress with an HFD model, which is more physiologically relevant. It was previously demonstrated that 16 wk of HFD feeding to mice induces ER stress in the liver (8). The HFD also produced ZIP14-mediated hepatic zinc accumulation in WT mice, whereas Zip14 KO mice did not accumulate zinc during that time period (Fig. 5C). The impaired hepatic zinc uptake of Zip14 KO mice possibly produced a greater signature of ER stress-induced apoptosis and steatosis, which is consistent with the TM-induced ER stress model (Fig. 5 D–F). Phenotypic changes in Zip14 KO mice, such as hepatic zinc accumulation and steatosis, are remarkably similar in those two models. However, the magnitude of change is relatively marginal in the HFD model compared with TM model. This difference may be caused by the chronic vs. acute nature of these two models of ER stress. The HFD is a well-known model of the metabolic syndrome, causing insulin resistance or glucose insensitivity (37). Our recent report has shown that HFD-fed (6 wk) Zip14 KO mice do not develop a disturbed metabolic phenotype, such as hepatic insulin resistance or glucose insensitivity (20), indicating that the impaired stress adaptation of Zip14 KO mice is probably not influenced by glucose stress, which is a known cause of ER stress (38).

Our first question regarding the zinc, ZIP14, and ER stress relationship was whether the increased hepatic zinc uptake after ER stress would be a factor in stress adaptation. In the sense that ER function is dependent on zinc availability to provide zinc for incorporation into and folding of zinc metalloproteins (39), increased zinc may play a role in the restoration of ER homeostasis. In support of that notion, it has been shown that a supply of zinc to the early secretory pathway via ZnT5, ZnT6, and ZnT7 is essential for helping protein folding via zinc incorporation into alkaline phosphatases, which are zinc metalloproteins (40, 41). The importance of an adequate zinc supply for protein folding was illustrated when TM-induced ER stress was exacerbated during zinc-deficient conditions in ZnT5−/−/ZnT7−/− cells (26). In contrast, some metals may exhibit toxicity when their cellular concentrations are elevated and can aggravate processes such as ER stress. For example, excessive accumulation of manganese (42–44), cadmium (45–47), and fluoride (48) induces ER stress and UPR activation. Here, we found that ZIP14-mediated zinc uptake was critical for adaptation to ER stress, because Zip14 KO mice displayed greater apoptosis (Figs. 2 D and E and 5D). The demonstration of impaired GRP94 expression in ER stress-induced Zip14 KO mice (Figs. 2D and 5D) supports the notion that GRP94 is a critical factor that supports recovery of ER homeostasis. Although ZIP14 can contribute to uptake of manganese and non–transferrin-bound iron under certain circumstances (49, 50), the hepatic concentration of these metals after TM administration was comparable between WT and Zip14 KO mice (Fig. S1 E and F). In support, in vitro supplementation with zinc rescued Zip14 KD HepG2 hepatocytes from ER stress-induced apoptosis (Fig. 3 B and D), demonstrating a direct effect of zinc. Because prolonged apoptosis causes many pathogenic disorders, suppression of the p-eIF2α/ATF4/CHOP pathway can be a therapeutic target. Our data collectively demonstrate that ZIP14-mediated hepatic zinc uptake also influences this pathway and provides a mechanism by which apoptosis is suppressed.

Our next focus was to elucidate a direct target for zinc. Here, we propose that zinc influences the p-eIF2α/ATF4/CHOP pathway through suppression of the activity of PTP1B. Various pathways, including the pathways for insulin and leptin signaling, are regulated by PTP1B, and dysregulation of PTP1B activity was demonstrated to contribute to the pathogenesis of various diseases, such as cancer and diabetes (51). Therefore, there has been a significant effort to develop a PTP1B inhibitor as a drug target (52). PTP1B has been implicated in ER stress (53). Liver-specific Ptp1b−/− mice showed decreased activation of the p-eIF2α/ATF4/CHOP pathway, along with reduced indices of metabolic syndrome, during TM- and HFD-induced ER stress (30, 31). Consequently, our data (Fig. 6 A and B) are consistent with the data from TM-treated Ptp1b KD hepatocytes. Zinc is a known inhibitor of PTP1B through physical binding to the enzyme (32). We previously reported that overexpression of ZIP14 in AML12 hepatocytes suppressed PTP1B activity (33). Based on these reports, we hypothesized that ER stress-induced mice increase hepatic ZIP14 expression to enhance zinc uptake for suppression of PTP1B activity. Zip14 KO mice showed significantly elevated PTP1B activity, whereas activity in WT mice remained unchanged after TM- and HFD-induced ER stress (Fig. 6 D and F), possibly due to impaired hepatic zinc uptake. In vitro, a direct effect of zinc on PTP1B activity inhibition was demonstrated using zinc supplementation, where the greater PTP1B activity in TM-treated Zip14 KD cells was reversed by zinc supplementation (Fig. 6H). These data are consistent with our previous study, where increased PTP1B activity was observed in mice fed a zinc-deficient diet compared with mice fed a zinc-adequate diet during TM challenge (25).

Disrupted hepatic lipid homeostasis is another hallmark of unresolved ER stress. This defect has been observed in cells with compromised UPR function. Genetic ablations of UPR components, including ATF6α, IRE1α, and eIF2α, result in the development of hepatic steatosis (14, 54, 55). Loss of ATF4 increased free cholesterol in rodent liver (35), and liver-specific deletion of XBP1 produced hypocholesterolemia and hypotriglyceridemia (56). Similar to these observations, the liver of Zip14 KO mice showed potentiated TG accumulation after TM administration due to enhanced FA synthesis (Fig. 4). Zinc-mediated PTP1B activity suppression may mechanistically explain these data because liver-specific Ptp1b−/− mice showed diminished hepatic FA synthesis and TG storage during HFD feeding (30), which is consistent with the ER stress-induced TG accumulation we showed in Zip14 KO mice.

UPR activation induces a variety of genes involved in protein folding, degradation, and trafficking to restore ER homeostasis via transcription factors, such as ATF6α, ATF4, and XBP-1 (12). We propose that one arm of UPR pathway activation is to modulate zinc trafficking, based on our finding that Zip14 is a transcriptional target of ATF4 and ATF6α (Fig. 7 E–H). ATF4 and ATF6α have a significant binding affinity for the CRE consensus sequence (57–59). We found that the Zip14 promoter has a CRE-like sequence, and demonstrated here that both ATF4 and ATF6α bound to the CRE-like sequence after TM treatment in a time-dependent manner, leading to Zip14 mRNA increases through increased transcription (Fig. 7). Our data agree with the observations from global transcriptional profiling, which showed significantly reduced Zip14 mRNA levels after TM treatment in liver-specific Atf4−/− mice (35) and in Atf6α−/− fibroblasts (34). ATF4 and ATF6α regulation of Zip14 suggests that these events lead to increased cellular zinc availability through ZIP14-mediated zinc transport. Of note is that the Zip14 promoter lacks the sequence required for the liver-specific transcription factor CREBH, which is needed for induction of hepcidin by ER stress (36). Limited evidence indicates that UPR components regulate expression of other zinc transporter genes. XBP-1–mediated hZnT5 up-regulation during ER stress occurs via direct binding to that promoter (26). In addition, ZnT5−/−/ZnT7−/− cells displayed an exacerbated ER stress response (26). Similarly, KD of Zip7, Zip13, and ZnT3 in cells induced ER stress and higher cell death, indicating the importance of normal zinc homeostasis for ER stress adaptation (27, 28, 60).

In conclusion, we demonstrate that ZIP14-mediated hepatic zinc uptake plays an important role in suppressing ER stress-induced apoptosis and hepatic steatosis (Fig. 8). ZIP14 displayed a protective effect against ER stress by influencing the proapoptotic p-eIF2α/ATF4/CHOP pathway and de novo FA synthesis through zinc-mediated inhibition of PTP1B activity. Deletion of Zip14 produced a phenotype presenting with hepatic lipid accumulation during ER stress. In addition, we demonstrated that Zip14 is transcriptionally regulated by ATF4 and ATF6α. The present findings document the importance of functional zinc transporter for adaptation to ER stress.

Materials and Methods

Mice and Diets.

Development and characterization of the murine Zip14−/− (KO) mice have been described previously (19). A colony of Zip14+/− heterozygotes on the C57BL/6/129S5 background was used to produce KO and Zip14+/+ (WT) mice. The mice were backcrossed on a mixed 129S5 and C57BL/6 background. Mice had free access to a chow diet (Teklad 7912; Harlan) and tap water, and were maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle. The same response to treatments was seen in both male and female mice in pilot experiments. Young adult (8–16 wk of age) male WT and KO mice were used for TM experiments. To model HFD-induced ER stress, WT and KO mice were fed either the chow diet (17 kcal% fat) containing 63 mg of zinc per kilogram as ZnO or an HFD (60 kcal% fat, D12492; Research Diets) containing 39 mg of zinc per kilogram as ZnCO3 for 16 wk.

Treatments.

ER stress was induced by i.p. administration of TM (Sigma) or thapsigargin (Sigma) dissolved in 1% DMSO/150 mM glucose at 2 mg/kg of body weight (TM) or 1 mg/kg of body weight (thapsigargin), respectively. To assess zinc absorption and tissue distribution, 65Zn (2 μCi; PerkinElmer) was given to mice by oral gavage 3 h before euthanasia. Accumulated 65Zn in tissue and plasma was measured by gamma scintillation spectrometry. Mice were anesthetized by isoflurane for injections and euthanasia by cardiac puncture. All mice were killed between 9:00 AM and 10:00 AM. Collected tissues were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. All animal protocols were approved by the University of Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Western Blot Analysis.

Tissue samples or cells were homogenized in radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Thermo Fisher) using Bullet Blender (Next Advance). Proteins were then separated by SDS/PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Polyclonal rabbit antibody against ZIP14 was raised in-house as described previously (61). Purchased antibodies were BiP, CHOP, and phosphorylated eIF2α (Ser52) (all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology); ATF4, GRP94, and PTP1B (all from Cell Signaling); ATF6 (Novus Bio); and tubulin (Abcam). Immunoreactivity was visualized by ECL reagents (Thermo Fisher). Immunoblots for ATF4, CHOP, and GRP94 were quantified using densitometry.

Statistical Analyses.

Results are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was analyzed using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software). Comparisons between two groups were conducted by the Student’s t test, and comparisons among multiple groups were conducted using ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

SI Materials and Methods

Biochemical Analyses.

Tissue and serum zinc concentrations were measured using flame atomic absorption spectrophotometry as described previously (19). Hepatic nonheme iron concentrations were analyzed colorimetrically (62). Serum alanine aminotransferase activity was measured using a colorimetric end-point assay (33). Liver TGs were measured using a colorimetric assay (BioVision Research) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cell Culture and siRNA KD.

Human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line HepG2 (American Type Culture Collection) was maintained in Dulbecco’s Modification of Eagle’s Medium (Corning) supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Sigma). Cells were maintained at 37 °C in 5% CO2. HiPerFect transfection reagent (Qiagen) was used to transfect siRNA for human Zip14 (4392420; Thermo Fisher), Atf4 (SI03018345; Qiagen), Atf6 (115887; Ambion), Ptp1b (13348; Cell Signaling), or negative control siRNA (Dharmacon) into cells at a final concentration of 5 nM according to each manufacturer’s instructions. The efficiency of KD was detected using quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) and immunoblotting. Cells were then treated with TM (1 μg/mL, unless specifically indicated otherwise) or vehicle (DMSO) to induce ER stress. In zinc supplementation experiments, zinc acetate (2.5–20 μM; Sigma) and pyrithione (2-mercaptopyridine N-oxide sodium salt, 50 µM; Sigma) were added to the culture medium for 30 min. To measure the total cellular zinc level, cells were sonicated to disrupt all cellular membranes, and the lysates were then incubated with the zinc fluorophore FluoZin3-AM (Invitrogen).

qPCR.

Total RNA from tissue samples or cells was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Ambion) and was homogenized using Bullet Blender (Next Advance). Isolated RNA was treated with Turbo DNA-free reagent (Ambion) to prevent DNA contamination. To determine mRNA expression, qPCR was performed using EXPRESS One-Step SuperScript Mix (Invitrogen). Amplification values were normalized to a value of TATA-binding protein (TBP) mRNA. The primer/probe sequences of genes involved in ER stress and lipid homeostasis are provided in the Table S1. The primer/probe sequences for zinc transporters have been provided previously (33).

In experiments detecting the transcriptional activity of Zip14, primers spanning the exon 5 and intron 5 junction of Zip14 were designed to measure unspliced heterogeneous nuclear RNA (hnRNA). The hnRNA was quantified by qPCR using SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems). The primer sequences used are provided in Table S1. The reaction conditions for PCR were 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 60 s, and a final cycle at 60 °C for 1 min. Melting curves were obtained after PCR to ensure only a single product was amplified.

Histological Analyses.

Collected liver tissues were embedded in paraffin after being fixed in 10% formalin, and were then sectioned to 4 μm in thickness. For histological analysis, the liver sections were stained with H&E. Lipid droplet areas in H&E-stained images were quantified using ImageJ software (National Institute of Mental Health). To detect apoptotic cells in the liver sections, an In Situ Apoptosis Detection Assay Kit (Abcam) was used following the manufacturer’s instructions.

PTP1B Assay.

Activity of PTP1B was analyzed as described previously (33), with slight modifications. To briefly describe the process, liver tissues or cells were homogenized in Hepes buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor mixture (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Obtained total lysates were centrifuged at 13,000 × g at 4 °C, and the supernatant was incubated with PTP1B-specific substrate (ELEF-pY-MDYE-NH2; AnaSpec) for 30 min at 30 °C. The inorganic phosphate level released during the incubation was measured using a colorimetric phosphate assay (Biovision). Assay values were normalized by total protein concentration.

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-Diphenyltetrazolium Bromide Assay.

The 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay in TM-treated HepG2 cells was performed using the MTT Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (Cayman Chemical) according to the manufacturer’s manual.

ChIP Assay.

ChIP assays were performed as described previously (63), with slight modifications. Briefly, TM or vehicle-treated HepG2 cells were cross-linked with 1.1% (vol/vol) formaldehyde for 10 min, followed by addition of 0.125 M glycine to stop cross-linking. Cells were lysed with nuclei swelling buffer [5 mM piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid) buffer (pH 8.0), 85 mM KCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40] and centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was then discarded. The pellet (nuclei) was resuspended in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer, followed by sonication using a BioRuptor (Diagenode) for 15 min (15 cycles of 30 s on and 30 s off on high power) to produce 200- to 500-bp DNA fragments. DNA fragment size after sonication was ensured by electrophoresis using a 1.6% agarose gel. Target DNA bound with protein was immunoprecipitated with ChIP-grade ATF6α antibody (Novus Bio) or ATF4 antibody (Cell Signaling). Thereafter, cross-link reagents and protein were removed. DNA was analyzed by qPCR with primers designed to detect the Zip14 promoter-binding site spanning potential ATF6α- or ATF4-binding sites or another downstream region that did not include the putative binding sites. The Zip14 promoter primers used are provided in Table S1.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH Grant R01DK94244 and the Boston Family Endowment of the University of Florida Foundation (to R.J.C.). M.-H.K. is an Alumni Graduate Fellow of the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1704012114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ellgaard L, Helenius A. Quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:181–191. doi: 10.1038/nrm1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nair S, et al. Toxicogenomics of endoplasmic reticulum stress inducer tunicamycin in the small intestine and liver of Nrf2 knockout and C57BL/6J mice. Toxicol Lett. 2007;168:21–39. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang X, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress induced by tunicamycin and thapsigargin protects against transient ischemic brain injury: Involvement of PARK2-dependent mitophagy. Autophagy. 2014;10:1801–1813. doi: 10.4161/auto.32136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ji C, Kaplowitz N. Betaine decreases hyperhomocysteinemia, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and liver injury in alcohol-fed mice. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1488–1499. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00276-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang K, Kaufman RJ. From endoplasmic-reticulum stress to the inflammatory response. Nature. 2008;454:455–462. doi: 10.1038/nature07203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li J, et al. Accumulation of endoplasmic reticulum stress and lipogenesis in the liver through generational effects of high fat diets. J Hepatol. 2012;56:900–907. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang K. Integration of ER stress, oxidative stress and the inflammatory response in health and disease. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2010;3:33–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ozcan U, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress links obesity, insulin action, and type 2 diabetes. Science. 2004;306:457–461. doi: 10.1126/science.1103160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schröder M, Kaufman RJ. ER stress and the unfolded protein response. Mutat Res. 2005;569:29–63. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.06.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baird TD, Wek RC. Eukaryotic initiation factor 2 phosphorylation and translational control in metabolism. Adv Nutr. 2012;3:307–321. doi: 10.3945/an.112.002113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walter P, Ron D. The unfolded protein response: From stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science. 2011;334:1081–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.1209038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rutkowski DT, et al. Adaptation to ER stress is mediated by differential stabilities of pro-survival and pro-apoptotic mRNAs and proteins. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshida H. ER stress and diseases. FEBS J. 2007;274:630–658. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rutkowski DT, et al. UPR pathways combine to prevent hepatic steatosis caused by ER stress-mediated suppression of transcriptional master regulators. Dev Cell. 2008;15:829–840. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King JC, Cousins RJ. Zinc. In: Shilis ME, editor. Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease. 11th Ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore: 2014. pp. 189–205. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kambe T, Tsuji T, Hashimoto A, Itsumura N. The physiological, biochemical, and molecular roles of zinc transporters in zinc homeostasis and metabolism. Physiol Rev. 2015;95:749–784. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00035.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeong J, Eide DJ. The SLC39 family of zinc transporters. Mol Aspects Med. 2013;34:612–619. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lichten LA, Cousins RJ. Mammalian zinc transporters: Nutritional and physiologic regulation. Annu Rev Nutr. 2009;29:153–176. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-033009-083312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aydemir TB, et al. Zinc transporter ZIP14 functions in hepatic zinc, iron and glucose homeostasis during the innate immune response (endotoxemia) PLoS One. 2012;7:e48679. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aydemir TB, Troche C, Kim MH, Cousins RJ. Hepatic ZIP14-mediated zinc transport contributes to endosomal insulin receptor trafficking and glucose metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:23939–23951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.748632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Troche C, Aydemir TB, Cousins RJ. Zinc transporter Slc39a14 regulates inflammatory signaling associated with hypertrophic adiposity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2016;310:E258–E268. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00421.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ellis CD, et al. Zinc and the Msc2 zinc transporter protein are required for endoplasmic reticulum function. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:325–335. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200401157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Homma K, et al. SOD1 as a molecular switch for initiating the homeostatic ER stress response under zinc deficiency. Mol Cell. 2013;52:75–86. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun Q, et al. Zinc deficiency mediates alcohol-induced apoptotic cell death in the liver of rats through activating ER and mitochondrial cell death pathways. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2015;308:G757–G766. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00442.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim MH, Aydemir TB, Cousins RJ. Dietary zinc regulates apoptosis through the phosphorylated eukaryotic initiation factor 2α/activating transcription factor-4/C/EBP-homologous protein pathway during pharmacologically induced endoplasmic reticulum stress in livers of mice. J Nutr. 2016;146:2180–2186. doi: 10.3945/jn.116.237495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishihara K, et al. Zinc transport complexes contribute to the homeostatic maintenance of secretory pathway function in vertebrate cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17743–17750. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602470200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeong J, et al. Promotion of vesicular zinc efflux by ZIP13 and its implications for spondylocheiro dysplastic Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:E3530–E3538. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211775110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurita H, Okuda R, Yokoo K, Inden M, Hozumi I. Protective roles of SLC30A3 against endoplasmic reticulum stress via ERK1/2 activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;479:853–859. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.09.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gu F, et al. Protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B potentiates IRE1 signaling during endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:49689–49693. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400261200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delibegovic M, et al. Liver-specific deletion of protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) improves metabolic syndrome and attenuates diet-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress. Diabetes. 2009;58:590–599. doi: 10.2337/db08-0913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agouni A, et al. Liver-specific deletion of protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) 1B improves obesity- and pharmacologically induced endoplasmic reticulum stress. Biochem J. 2011;438:369–378. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bellomo E, Massarotti A, Hogstrand C, Maret W. Zinc ions modulate protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B activity. Metallomics. 2014;6:1229–1239. doi: 10.1039/c4mt00086b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aydemir TB, Sitren HS, Cousins RJ. The zinc transporter Zip14 influences c-Met phosphorylation and hepatocyte proliferation during liver regeneration in mice. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1536–1546.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu J, et al. ATF6alpha optimizes long-term endoplasmic reticulum function to protect cells from chronic stress. Dev Cell. 2007;13:351–364. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fusakio ME, et al. Transcription factor ATF4 directs basal and stress-induced gene expression in the unfolded protein response and cholesterol metabolism in the liver. Mol Biol Cell. 2016;27:1536–1551. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E16-01-0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vecchi C, et al. ER stress controls iron metabolism through induction of hepcidin. Science. 2009;325:877–880. doi: 10.1126/science.1176639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buettner R, Schölmerich J, Bollheimer LC. High-fat diets: Modeling the metabolic disorders of human obesity in rodents. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:798–808. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee AS. The glucose-regulated proteins: Stress induction and clinical applications. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26:504–510. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01908-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eide DJ. Zinc transporters and the cellular trafficking of zinc. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:711–722. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suzuki T, et al. Zinc transporters, ZnT5 and ZnT7, are required for the activation of alkaline phosphatases, zinc-requiring enzymes that are glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored to the cytoplasmic membrane. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:637–643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411247200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suzuki T, et al. Two different zinc transport complexes of cation diffusion facilitator proteins localized in the secretory pathway operate to activate alkaline phosphatases in vertebrate cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30956–30962. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506902200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chun HS, Lee H, Son JH. Manganese induces endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and activates multiple caspases in nigral dopaminergic neuronal cells, SN4741. Neurosci Lett. 2001;316:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02341-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oubrahim H, Chock PB, Stadtman ER. Manganese(II) induces apoptotic cell death in NIH3T3 cells via a caspase-12-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:20135–20138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200226200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seo YA, Li Y, Wessling-Resnick M. Iron depletion increases manganese uptake and potentiates apoptosis through ER stress. Neurotoxicology. 2013;38:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hiramatsu N, et al. Rapid, transient induction of ER stress in the liver and kidney after acute exposure to heavy metal: Evidence from transgenic sensor mice. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:2055–2059. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Biagioli M, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and alteration in calcium homeostasis are involved in cadmium-induced apoptosis. Cell Calcium. 2008;43:184–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kitamura M, Hiramatsu N. The oxidative stress: Endoplasmic reticulum stress axis in cadmium toxicity. Biometals. 2010;23:941–950. doi: 10.1007/s10534-010-9296-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kubota K, et al. Fluoride induces endoplasmic reticulum stress in ameloblasts responsible for dental enamel formation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:23194–23202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503288200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liuzzi JP, Aydemir F, Nam H, Knutson MD, Cousins RJ. Zip14 (Slc39a14) mediates non-transferrin-bound iron uptake into cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13612–13617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606424103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pinilla-Tenas JJ, et al. Zip14 is a complex broad-scope metal-ion transporter whose functional properties support roles in the cellular uptake of zinc and nontransferrin-bound iron. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;301:C862–C871. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00479.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zabolotny JM, et al. PTP1B regulates leptin signal transduction in vivo. Dev Cell. 2002;2:489–495. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00148-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang S, Zhang ZY. PTP1B as a drug target: Recent developments in PTP1B inhibitor discovery. Drug Discov Today. 2007;12:373–381. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Popov D. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the on site function of resident PTP1B. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;422:535–538. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yamamoto K, et al. Induction of liver steatosis and lipid droplet formation in ATF6alpha-knockout mice burdened with pharmacological endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:2975–2986. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-02-0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang K, et al. The unfolded protein response transducer IRE1α prevents ER stress-induced hepatic steatosis. EMBO J. 2011;30:1357–1375. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee AH, Scapa EF, Cohen DE, Glimcher LH. Regulation of hepatic lipogenesis by the transcription factor XBP1. Science. 2008;320:1492–1496. doi: 10.1126/science.1158042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang Y, et al. Activation of ATF6 and an ATF6 DNA binding site by the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27013–27020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003322200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koyanagi S, et al. cAMP-response element (CRE)-mediated transcription by activating transcription factor-4 (ATF4) is essential for circadian expression of the Period2 gene. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:32416–32423. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.258970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Luo S, Baumeister P, Yang S, Abcouwer SF, Lee AS. Induction of Grp78/BiP by translational block: Activation of the Grp78 promoter by ATF4 through and upstream ATF/CRE site independent of the endoplasmic reticulum stress elements. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:37375–37385. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303619200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ohashi W, et al. Zinc transporter SLC39A7/ZIP7 promotes intestinal epithelial self-renewal by resolving ER stress. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1006349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liuzzi JP, et al. Interleukin-6 regulates the zinc transporter Zip14 in liver and contributes to the hypozincemia of the acute-phase response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:6843–6848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502257102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rebouche CJ, Wilcox CL, Widness JA. Microanalysis of non-heme iron in animal tissues. J Biochem Biophys Methods. 2004;58:239–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jbbm.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xie L, Collins JF. Transcription factors Sp1 and Hif2α mediate induction of the copper-transporting ATPase (Atp7a) gene in intestinal epithelial cells during hypoxia. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:23943–23952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.489500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]