Significance

The human pathogen Staphylococcus aureus forms biofilms in which cells are held together in clusters by an electrostatic net of extracellular DNA (eDNA). How eDNA is released from cells to form this net is unknown. We report the development of a genetic approach to identifying genes involved in eDNA release. This approach should be generally amenable to identifying genes involved in eDNA release by other biofilm-forming bacteria that aggregate in a DNA-containing matrix. The genes we identified in S. aureus provide fresh insights into how eDNA is released and provide potential therapeutic targets for drug development.

Keywords: Staphylococcus aureus, biofilm, eDNA, cyclic-di-AMP

Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus is a leading cause of both nosocomial and community-acquired infection. Biofilm formation at the site of infection reduces antimicrobial susceptibility and can lead to chronic infection. During biofilm formation, a subset of cells liberate cytoplasmic proteins and DNA, which are repurposed to form the extracellular matrix that binds the remaining cells together in large clusters. Using a strain that forms robust biofilms in vitro during growth under glucose supplementation, we carried out a genome-wide screen for genes involved in the release of extracellular DNA (eDNA). A high-density transposon insertion library was grown under biofilm-inducing conditions, and the relative frequency of insertions was compared between genomic DNA (gDNA) collected from cells in the biofilm and eDNA from the matrix. Transposon insertions into genes encoding functions necessary for eDNA release were identified by reduced representation in the eDNA. On direct testing, mutants of some of these genes exhibited markedly reduced levels of eDNA and a concomitant reduction in cell clustering. Among the genes with robust mutant phenotypes were gdpP, which encodes a phosphodiesterase that degrades the second messenger cyclic-di-AMP, and xdrA, the gene for a transcription factor that, as revealed by RNA-sequencing analysis, influences the expression of multiple genes, including many involved in cell wall homeostasis. Finally, we report that growth in biofilm-inducing medium lowers cyclic-di-AMP levels and does so in a manner that depends on the gdpP phosphodiesterase gene.

Biofilms are communities of microbial cells that are generally attached to a surface and are held together by an extracellular matrix. Matrix components are often produced by the cells that make up the biofilm and serve as a natural glue, connecting neighboring cells to one another. Biofilms formed by pathogens, including Staphylococcus, have been shown to contribute to the recalcitrance of infections, in part due to enhanced antibiotic tolerance conferred by the matrix itself, which can reduce penetration of antimicrobial agents (1, 2).

Bacteria use a variety of strategies to form biofilms, and even among Staphylococcus aureus, different strains use distinctive strategies. Antibiotic resistance appears to be linked to biofilm-formation, with methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) strains more likely to require the polysaccharide intercellular adhesin (PIA), whose production is governed by the ica operon, whereas methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strains most often form biofilms in a PIA-independent, glucose-dependent manner (3). Here, we report the identification of genes that are important for the release of extracellular DNA (eDNA) in biofilms formed by a strain of S. aureus [HG003, a virulent derivative of multilocus sequence type (MLST) ST8 strain NCTC8325 repaired for two regulatory genes; ref. 4], which is MSSA, but forms ica-independent biofilms similarly to MRSA strains.

We have shown that the major components of the biofilm matrix of HG003 are proteins and eDNA, which associate with the biofilm in a manner that depends on a drop in pH during growth in the presence of glucose (5, 6). Many of these proteins are cytoplasmic in origin and are thus moonlighting in their second role as components of the biofilm matrix (5). These moonlighting proteins do not depend on eDNA to remain associated with cells. The eDNA, however, requires the presence of matrix proteins to adhere to the cells, serving as an electrostatic net that holds cells together in large clumps (6). eDNA is a critical component of the matrix of the HG003 staphylococcal biofilm, because DNase I treatment of biofilm cells leads to a marked reduction in clumping and a partial reduction in biofilm biomass (6).

How components of the biofilm matrix are externalized remains to be fully understood. Lysis of a subset of cells seems a likely candidate, and mutants defective in autolysis have been found to have reduced biofilm formation ability in some PIA-independent strains (7). Other known mechanisms of eDNA release include prophage-mediated cell death (8), and lysis-independent methods such as vesicle formation (9) or specialized secretion (10). It is possible that one or more of these release mechanisms contributes to the externalization of S. aureus biofilm matrix components.

Here, we sought to identify genes required for the release of eDNA by using a comprehensive genome-wide transposon-sequencing approach. We took advantage of an earlier observation that the eDNA component of the biofilm matrix is released into the medium when the cells are suspended in a buffer at a higher pH (6). This method enabled us to separate eDNA in the matrix from genomic DNA (gDNA), which we extracted from cells in the biofilm. We report the identification of several genes in which transposon insertions were underrepresented in eDNA, compared with their occurrence in gDNA. Upon direct testing, mutants of some of these genes were markedly defective in eDNA release and cell clumping during biofilm formation. Among these genes were gdpP, which encodes a phosphodiesterase that acts on the second messenger cyclic-di-AMP, and xdrA, which encodes a transcription factor that had not previously been implicated in biofilm formation. We further show that growth under glucose supplementation, which is required for biofilm formation, lowers cyclic-di-AMP levels in wild-type cells but not in a gdpP mutant.

Results

Comprehensive Strategy for Identifying Genes Involved in eDNA Release.

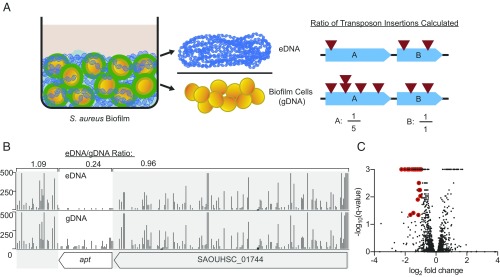

We used a high-density library of transposon insertions in a biofilm-proficient strain of S. aureus (11) to screen for those that impair release of eDNA and, hence, biofilm formation. Under biofilm-inducing conditions, extracellular complementation would mask insertions that fail to contribute eDNA because these mutants would be retained in the biofilm by virtue of the eDNA released by other cells in the population. To circumvent this problem, we took advantage of a prior observation that mature biofilms release their matrix, including the eDNA component, when the cells are suspended at a neutral pH (7.5) buffer (6). We therefore grew a biofilm using a mixed inoculum representing a highly saturated transposon library and proceeded to isolate eDNA recovered by neutralization of the biofilm environment. gDNA was then extracted from cells in the biofilm that had been freed from the eDNA, and the frequency of transposon insertion in or near various genes was compared between the two DNA samples. We reasoned that transposon insertions in genes involved in the release of eDNA would be underrepresented in eDNA compared with gDNA (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Identifying genes involved in eDNA release. (A) Strategy overview: Cells of the HG003 transposon library were grown under biofilm-inducing conditions and then separated into eDNA and biofilm cell fractions. DNA was extracted from the biofilm cells, representing gDNA. Sequencing reads from eDNA and gDNA then were mapped to the genome, and the ratios of transposon insertions in eDNA and gDNA was computed for each gene. Shown in the hypothetical example on the right, gene A has fewer transposon insertions in eDNA than in gDNA and is therefore potentially required for release of eDNA. In contrast, gene B is not required for eDNA release. Henceforth, we focused on genes in category A. (B) Shown here is an example of a gene (apt) underrepresented in reads per TA site in eDNA (Upper) compared with gDNA (Lower). The apt gene is flanked by regions of the chromosome highlighted in gray, which show little to no differential representation of reads. (C) Volcano plot showing all transposon screen results. The x axis displays log2-fold change, and the y axis displays the negative log10 of the q value (those genes with 0 q value were given a value of 0.001 for plotting purposes). Genes with log2-fold change ≤ −1 and q < 0.05, which did not appear to be essential based on the frequency of transposon insertions, are highlighted in red.

Identification of Transposon Insertions in Genes Underrepresented in eDNA.

Cells of the pooled mutant library were grown under biofilm-inducing conditions, and biofilms were harvested at 6 and 8 h. Preliminary studies had indicated that eDNA release is at its peak during this window (12). Because of the potential risk of population bottlenecks stemming from varying representation of the mutant library in different experiments, the experiment was repeated at both time points. eDNA and gDNA were isolated from biofilms, and sites of transposon insertions were sequenced and identified. The relative number of reads corresponding to each insertion was compared between the eDNA and gDNA samples (Fig. 1B). We identified 36 genes that possessed significantly more transposon insertions (q value of less than 0.05) in the gDNA than in the biofilm-associated eDNA (Fig. 1C), in one or more of the transposon construct categories (all, blunt, Perm, and other; Materials and Methods). These genes had, at minimum, a log2-fold change of less than or equal to −1, and did not appear to be essential (Table 1 and Dataset S1). In preliminary tests conducted to optimize conditions, which used a lower density transposon insertion library (13), eight of the genes listed in Table 1 (alsT, fmtA, ptsI, SAOUHSC_00034, recF, tcyA, ansA, and lpl2A) were also identified by using the same cutoff criteria.

Table 1.

Transposon insertions in genes underrepresented in eDNA

| Functional category | Locus tag | Gene | Product | Log2-FC |

| Transporter | SAOUHSC_01354 | alsT | Sodium:alanine symporter family protein | −1.8 |

| Transporter | SAOUHSC_01028 | ptsH | Phosphocarrier protein HPr | −1.7 |

| Transporter | SAOUHSC_01029 | ptsI | Phosphoenolpyruvate-protein phosphotransferase | −1.3 |

| Transporter | SAOUHSC_00420 | — | Sodium-dependent transporter | −1.3 |

| Transporter | SAOUHSC_00880 | yuiF | Putative amino acid transporter | −1.2 |

| Transporter | SAOUHSC_02699 | tcyA | Hypothetical protein, putative l-cystine ABC transporter | −1.2 |

| Transporter | SAOUHSC_00670 | pitA | Hypothetical protein, putative inorganic phosphate transporter | −1.1 |

| Transporter | SAOUHSC_03037 | vraE | Bacitracin transport system permease protein | −0.9* |

| Transporter | SAOUHSC_00636 | mntB | Iron (chelated)/manganese ABC transporter permease | −0.8* |

| Transcriptional regulator | SAOUHSC_01979 | xdrA | Transcriptional regulator | −1.8 |

| Transcriptional regulator | SAOUHSC_00620 | sarA | Accessory regulator A | −1.6* |

| Transcriptional regulator | SAOUHSC_01586 | srrA | DNA binding response regulator SrrA | −1.6 |

| Transcriptional regulator | SAOUHSC_00034 | — | Hypothetical protein, putative transcriptional repressor | −1.5 |

| Transcriptional regulator | SAOUHSC_01850 | ccpA | Catabolite control protein A | −1.0 |

| Transcriptional regulator | SAOUHSC_02273 | rex | Redox-sensing transcriptional repressor Rex | −0.9* |

| Glycolysis/TCA cycle | SAOUHSC_00798 | pgm | Phosphoglyceromutase | −1.4 |

| Glycolysis/TCA cycle | SAOUHSC_01042 | pdhC | Branched-chain alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase subunit E2 | −1.2 |

| Glycolysis/TCA cycle | SAOUHSC_01040 | pdhA | Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, E1 component subunit alpha | −1.1 |

| Glycolysis/TCA cycle | SAOUHSC_01041 | pdhB | Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, E1 component subunit beta | −0.9* |

| Nucleotide metabolism | SAOUHSC_01743 | apt | Adenine phosphoribosyltransferase | −2.0 |

| Nucleotide metabolism | SAOUHSC_00467 | purR | Purine operon repressor | −1.3 |

| Nucleotide metabolism | SAOUHSC_02353 | upp | Uracil phosphoribosyltransferase | −1.1 |

| ATP-synthase | SAOUHSC_02341 | atpD | F0F1 ATP synthase subunit beta | −1.1 |

| ATP-synthase | SAOUHSC_02346 | atpH | F0F1 ATP synthase subunit delta | −1.0 |

| ATP-synthase | SAOUHSC_02343 | atpG | F0F1 ATP synthase subunit gamma | −0.9* |

| Cell wall-related | SAOUHSC_00998 | fmtA | Methicillin resistance protein FmtA | −2.2 |

| Cell wall-related | SAOUHSC_01025 | — | Hypothetical protein | −1.5 |

| Other functions | ||||

| Cyclic-di-AMP | SAOUHSC_00015 | gdpP | Cyclic-di-AMP phosphodiesterase | −1.7 |

| Protein modification | SAOUHSC_00575 | lplA2 | Octanoyl-[GcvH]:protein N-octanoyltransferase | −1.4 |

| tRNA modification | SAOUHSC_03052 | gidA | tRNA uridine 5-carboxymethylaminomethyl modification enzyme | −1.3* |

| Uncharacterized | SAOUHSC_00755 | — | Hypothetical protein | −1.2 |

| Amino acid metabolism | SAOUHSC_01497 | ansA | l-Asparaginase | −1.0 |

| Uncharacterized | SAOUHSC_00014 | yybS | Hypothetical protein (just upstream of gdpP) | −1.0 |

| Uncharacterized | SAOUHSC_03047 | — | Hypothetical protein | −1.0 |

| Integrase/recombinase | SAOUHSC_03040 | — | Integrase/recombinase | −0.9* |

| DNA repair | SAOUHSC_00004 | recF | Recombination protein F | −0.8* |

Log2-FC, log2-fold change for the “All” comparison, which included all transposon constructs.

Indicates that the cutoff criteria were not satisfied in this comparison (see Dataset S1 for full results).

Several genes identified in this eDNA release screen are involved in nucleotide metabolism. These genes include apt and upp, which enable nucleotide salvage reactions, and purR, which encodes a repressor of de novo purine synthesis (14). Disruption of any of these three genes would lead to increased de novo nucleotide synthesis. We also identified another gene involved in purine nucleotide metabolism, gdpP, which encodes a phosphodiesterase that cleaves the second messenger cyclic-di-AMP (15). Additionally, members of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex pdhA, pdhB, and pdhC were identified, disruption of which could lead to an increase in pyruvate metabolism by pyruvate formate lyase (Pfl), thereby increasing cellular formate levels. Formate produced by Pfl is used to generate formyl-THF and methenyl-THF, both of which are precursors for purine metabolism.

A second category of genes was those involved in glycolysis and respiration, mutations of which would enhance anaerobic respiration and fermentation. These genes include those for components of ATP synthase, CcpA (16), Rex (17), and SrrA (18).

Finally, we note that our dataset also yielded genes that were overrepresented for transposon insertions in the eDNA, with a log2-fold change of greater than or equal to 1 (Dataset S2).

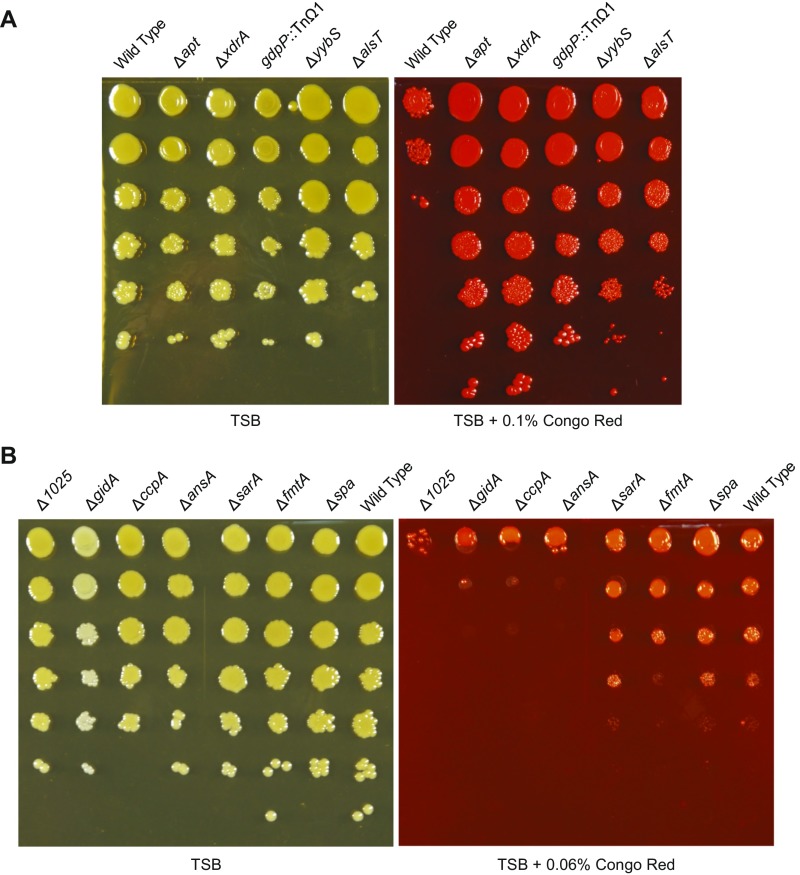

Mutants of Genes Underrepresented for Transposon Insertions Exhibit Reduced Levels of eDNA.

Next, we asked whether the genes identified in our screen are needed for the release of eDNA during biofilm formation when the mutants are grown individually in pure culture. We constructed null mutants for nine of these genes (∆yybS, ∆fmtA, ∆1025, ∆alsT, ∆ansA, ∆apt, ∆ccpA, ∆xdrA, ∆gidA) in the present work, and also used a previously generated mutant (∆sarA) (6). Additionally, a transposon insertion in an 11th gene, gdpP, was recovered by using a strategy described below.

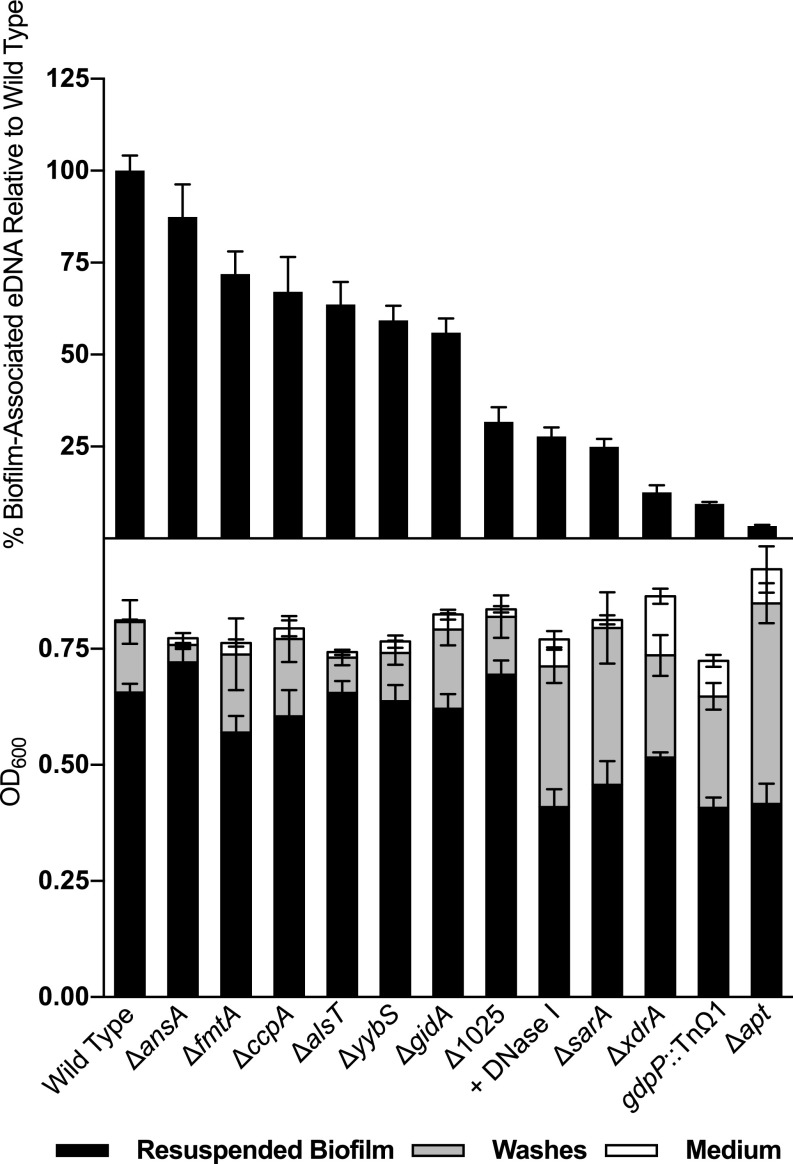

Quantitative measurements of eDNA released from these strains revealed that in mature (24 h) biofilms, wild-type HG003 released more eDNA than any of the deletion mutants, among which eDNA release varied widely (Fig. 2, Upper). In sum, we observed a slight reduction in eDNA levels in ∆ansA, ∆fmtA, ∆ccpA, ∆alsT, ∆yybS, and ∆gidA mutants, and comparatively large reductions in eDNA release by ∆1025, ∆sarA, ∆xdrA, ∆apt, and gdpP::TnΩ1 mutants. These large reductions were at or below the eDNA level observed following DNase I treatment of wild-type biofilms (Fig. 2, Upper).

Fig. 2.

Quantification of eDNA and biofilm formation by wild-type and mutant cells. Upper shows eDNA quantification normalized to wild-type HG003 levels, in order of increasingly severe effects on eDNA levels. Lower shows absolute biofilm quantification for biofilms collected 24 h after inoculation by the indicated mutants, or by HG003 with DNase I treatment. Significant differences were calculated with Student’s t test, comparing to wild type in each case. For eDNA, ∆ansA had a P ≤ 0.01, and all other strains had P ≤ 0.0001. For resuspended biofilm measurements, the reductions observed upon DNase I treatment, and for ∆sarA, ∆xdrA, gdpP::TnΩ1, and ∆apt, were significant, with P ≤ 0.0001.

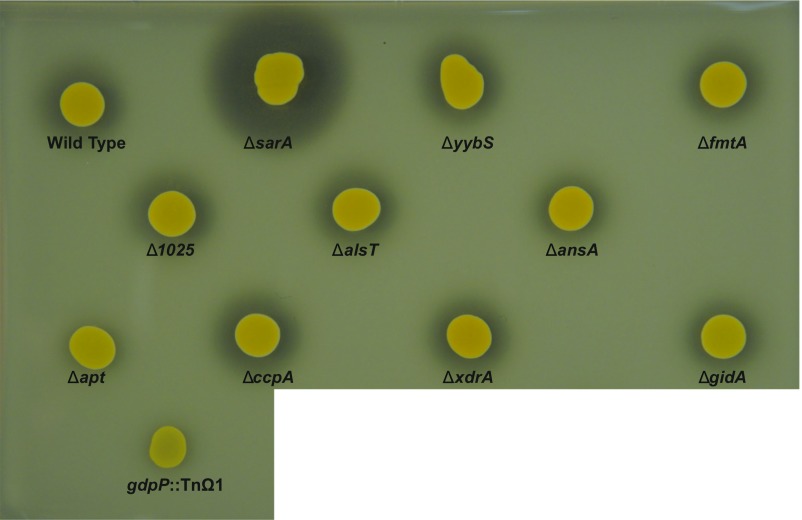

Previous studies have shown increased extracellular nuclease production in a ∆sarA mutant background, which contributes to reduced biofilm formation in this strain (19, 20). We spotted cultures of our mutant strains onto DNase test agar plates to determine whether enhanced extracellular nuclease levels could be the cause of the reduction in eDNA levels. Only the ∆sarA strain exhibited enhanced extracellular nuclease production (Fig. S1).

Fig. S1.

DNase test agar results for mutant strains. Overnight cultures of wild-type HG003 and its mutant derivatives were spotted onto DNase test agar, incubated overnight, flooded with 1 M HCl, and imaged.

Finally, we note that the 11 genes analyzed above represent only a portion of the genes identified in our genome-wide screen (Table 1). It will be interesting to see whether the as yet uncharacterized genes also play a role in eDNA release.

A gdpP Mutation in a Different Genetic Background Also Causes Reduced Levels of eDNA.

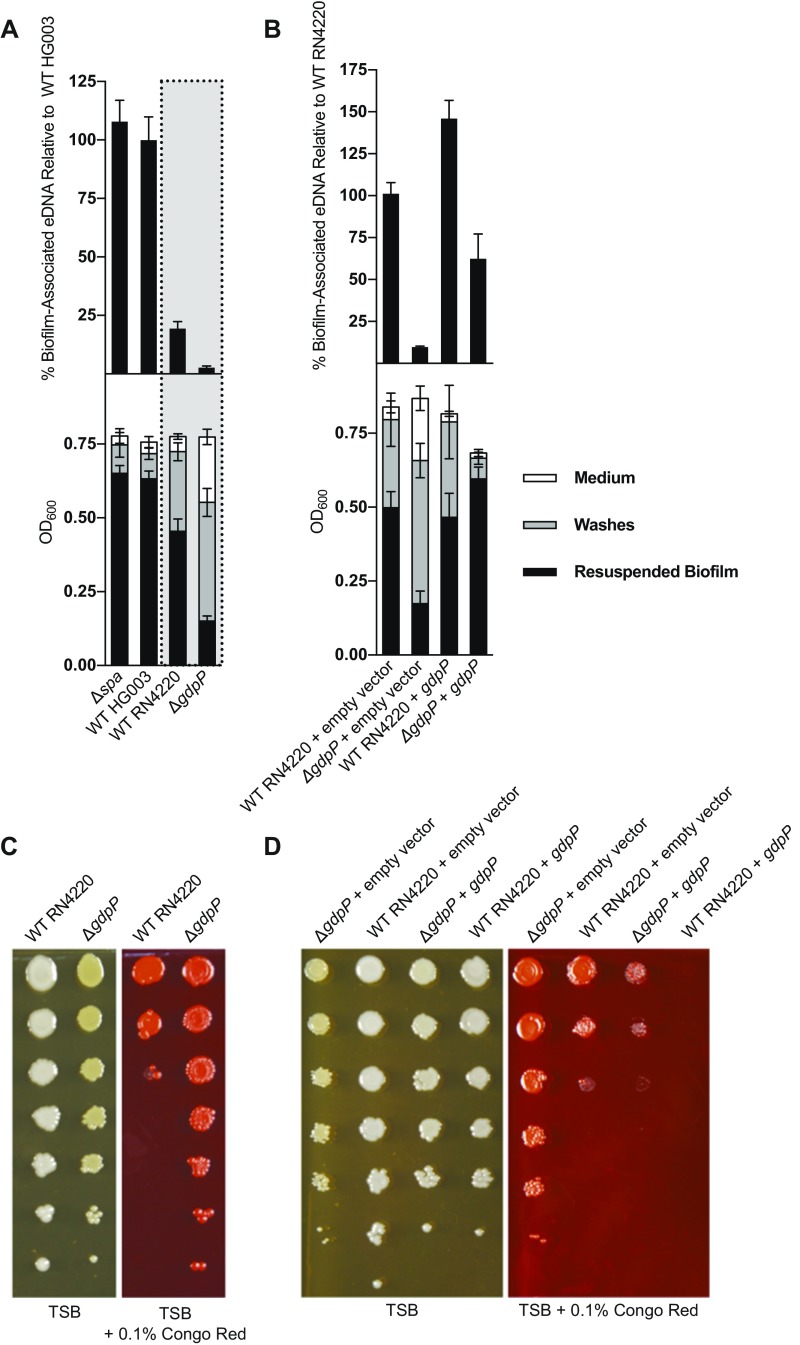

The gdpP gene was of special interest because of its role in controlling the levels of the second messenger cyclic-di-AMP, which could act as a signaling molecule to regulate biofilm formation. We therefore investigated the effect of a gdpP deletion mutation in a different genetic background. We used strain ANG1958 from the Gründling laboratory, which was constructed in the RN4220 strain background and also contains a ∆spa mutation (15). Although RN4220 is from the same parental NCTC8325 parental lineage as HG003 (4), it releases less eDNA during biofilm formation than does HG003 (Fig. S2A, Upper, gray box). Nonetheless, the ∆gdpP, ∆spa mutant released significantly less eDNA than did RN4220. The ∆spa mutation in RN4220 was likely not responsible for this effect, given that a ∆spa mutant (gdpP+) derivative of HG003 was unimpaired in eDNA release (Fig. S2A, Upper). We confirmed that the gdpP mutation was responsible for reducing eDNA levels by complementing both the transposon insertion mutation and the deletion mutation with a wild-type copy of gdpP under its native promoter. The complemented gdpP mutant strains showed markedly increased levels of eDNA over their parent strains (Fig. S2B, Upper for ANG1958 and Fig. S3A, Upper for gdpP::TnΩ1). We conclude that gdpP contributes to eDNA release and does so in two different genetic backgrounds.

Fig. S2.

eDNA, biofilm, and Congo red resistance in an RN4220 ∆gdpP∆spa mutant and complemented strain. (A) Upper shows eDNA quantification normalized to wild-type HG003 levels. Lower shows absolute biofilm quantification for biofilms collected 24 h after inoculation by the indicated mutants. The ∆spa mutant is a derivative of HG003. The wild-type strain within the gray box is RN4220. The ∆gdpP mutant, ANG1958, harbors ΔgdpP and Δspa and is derived from RN4220. For both eDNA and resuspended biofilm measurements, there was no significant difference between WT HG003 and ∆spa (P > 0.05), but reductions observed between WT HG003 and WT RN4220, and between WT RN4220 and ∆gdpP (for both eDNA and biofilm measurements) were significant, with P ≤ 0.0001. (B) Quantification of eDNA and biofilm for complemented ∆gdpP mutant. Upper shows eDNA quantification normalized to RN4220 + empty vector levels. Lower shows absolute biofilm quantification for biofilms collected 24 h after inoculation by the indicated strains. Empty vector (pASD145) confers erythromycin resistance, whereas the gdpP complementation plasmid (pASD135) is an erythromycin resistance-conferring plasmid with a copy of gdpP under native promoter control. eDNA measurements were significantly different between all strains tested, with P ≤ 0.0001. For resuspended biofilm measurements, there was no significant difference between WT RN4220 + empty vector and WT RN4220 + gdpP (P > 0.05), but the reduction observed between RN4220 + empty vector and ∆gdpP + empty vector, and the restored biofilm (comparing ∆gdpP + empty vector to ∆gdpP + ∆gdpP) were significant with P ≤ 0.0001. (C) Overnight cultures of RN4220 and ∆gdpP (ANG1958) were serially diluted, spotted onto agar plates with or without 0.1% Congo red, incubated overnight, and imaged. (D) Congo red resistance phenotypes with complementation constructs described above.

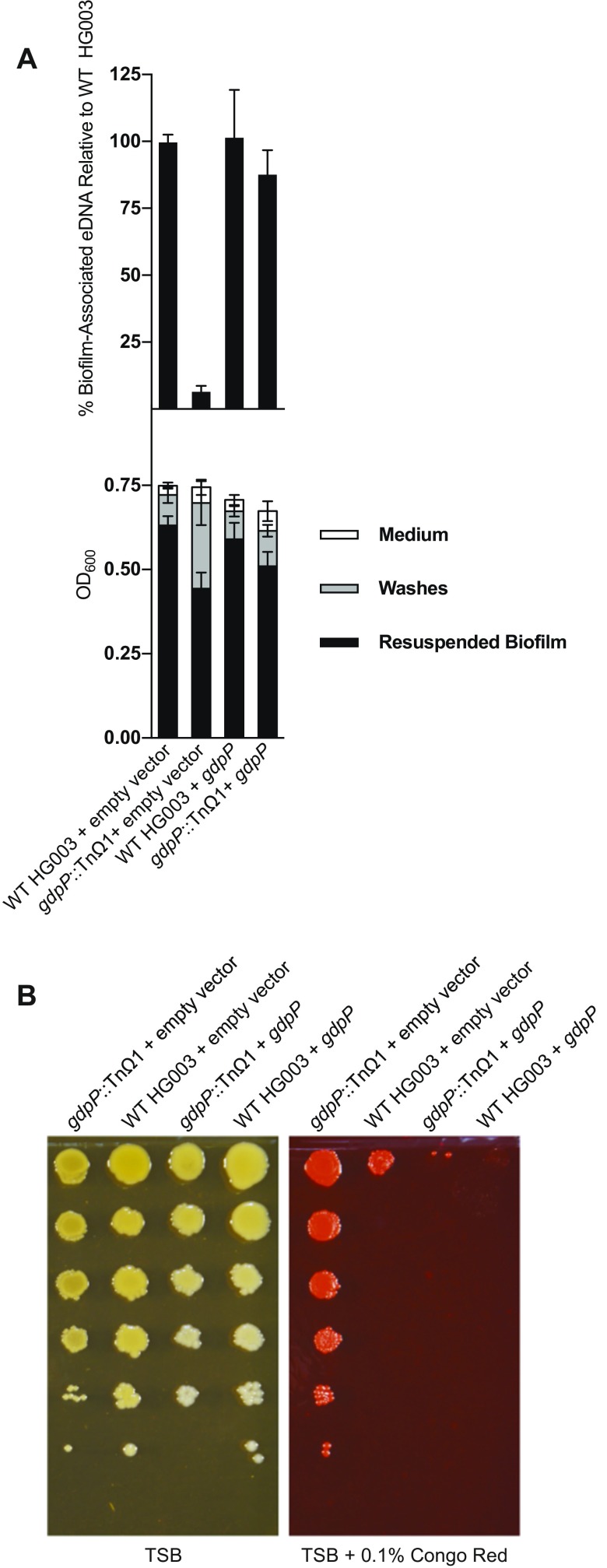

Fig. S3.

Complementation of gdpP::TnΩ1 strain. (A) Quantification of eDNA and biofilm mass for complemented gdpP::TnΩ1 mutant. Upper shows eDNA quantification normalized to HG003 + empty vector levels. Lower shows absolute biofilm quantification for biofilms collected 24 h after inoculation by the indicated strains. Empty vector (pASD132) confers chloramphenicol resistance, whereas the gdpP complementation plasmid (pASD133) is a chloramphenicol resistance-conferring plasmid with a copy of gdpP under native promoter control. The reduced eDNA observed between WT HG003 and gdpP::TnΩ1 with empty vector was significant (P ≤ 0.0001), as was the restored eDNA level observed upon complementation of gdpP (comparing gdpP::TnΩ1 + empty vector to gdpP::TnΩ1 + gdpP; P ≤ 0.0001). For resuspended biofilm measurements, the reduction observed between WT HG003 and gdpP::TnΩ1 with empty vector was significant (P ≤ 0.0001), and upon complementation of gdpP (comparing gdpP::TnΩ1 + empty vector to gdpP::TnΩ1 + gdpP), the biofilm level increase was also significant (P ≤ 0.01). (B) Congo red resistance phenotypes with complementation constructs described above.

Mutants with a Large Reduction in eDNA Are Impaired in Biofilm Formation.

Along with measuring the levels and representation of various insertion mutations in biofilm-associated eDNA, we quantified the ability of the individual mutants to form biofilms. As described, we grew various engineered null mutants under biofilm-inducing conditions, and compared the optical densities of the resuspended, washed biofilm, the recovered wash, and medium fractions (5). Only four mutants, ∆sarA, ∆xdrA, ∆apt, and gdpP::TnΩ1, were found to produce reduced levels of biofilm in monoculture (Fig. 2, Lower). Strains harboring ∆sarA, ∆xdrA, ∆apt, and gdpP::TnΩ1 exhibited the most severe impairment in eDNA release relative to the HG003 parental strain. This observation indicates that reduction below a threshold of ∼25% of the wild-type level of eDNA release is required to significantly reduce biofilm formation in HG003 under the conditions of our experiments. We also conclude that biofilm formation, as judged by the OD600 of washed biofilms, is only partially impaired even when eDNA is reduced to low levels. In particular, the ∆apt mutant released less than 2% of the amount of eDNA as that by the wild-type parental strain, but still formed a biofilm of 60% of the optical density of the wild-type biofilm–the same level that was seen with DNase I treatment (Fig. 2, Lower).

The ANG1958 ∆gdpP mutant also showed a partial reduction in biofilm formation relative to its parent RN4220 (Fig. S2A, Lower), and biofilm formation was restored by complementation (Fig. S2B, Lower).

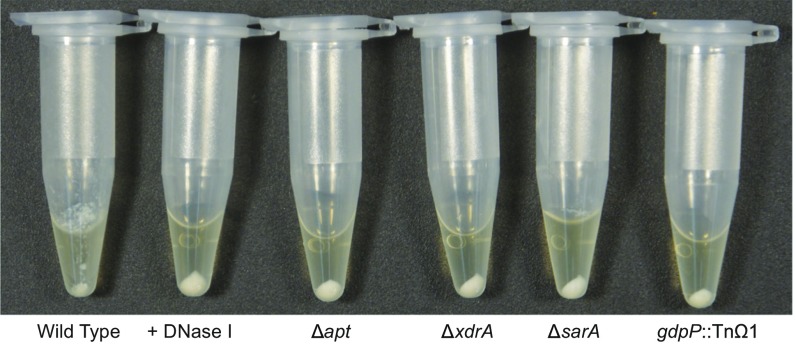

Cell Clumping Is Markedly Reduced in Low-eDNA Mutants.

Whereas reduced eDNA release only results in a modest reduction in biofilm formation, as inferred from turbidity measurements, it has a profound effect on cell clumping, as judged by microscopic examination of DNase I-treated biofilms (6). We therefore hypothesized that mutants that liberate reduced eDNA levels would similarly show a marked reduction in clumping. To investigate this hypothesis, mutants defective in eDNA release were grown under biofilm-inducing conditions, concentrated by centrifugation, and gently resuspended in a smaller volume of the remaining spent medium before imaging. During initial concentration of the cells, the wild-type cell pellet was notably more diffuse than the other pellets, which were compact (Fig. S4). This result is akin to the phenotype seen in traditional agglutination assays, in which agglutinated erythrocytes or yeast cells form diffuse pellets, whereas nonagglutinated cells form compact pellets (21, 22). Imaging revealed that the wild-type cells were in large clumps, whereas the mutant cells and DNase I-treated cells were in much smaller clumps (Fig. 3). Clumping was dramatically reduced for the four mutant derivatives of HG003 that were most reduced in eDNA release: ∆apt, gdpP::TnΩ1, ∆xdrA, and ∆sarA. These results are consistent with the idea that eDNA serves as an electrostatic net that links cells together in biofilm formation.

Fig. S4.

Wild-type strain shows more diffuse pellet following centrifugation of biofilm cells. Biofilms of wild-type HG003 and mutant derivatives most deficient in eDNA were grown (with the addition of DNase I in the indicated sample), resuspended in a subset of growth medium, briefly centrifuged to concentrate cells, and pellets were imaged.

Fig. 3.

Cell clumping is reduced in mutants with reduced eDNA. Twenty-four-hour biofilms were grown by using wild-type HG003 and mutant derivatives most deficient in eDNA release, cells were resuspended in spent medium and imaged. HG003 with DNase I treatment is shown for comparison. Scale bars in the lower right corner of DNase I images are 15 μm wide in the higher magnification image and 200 μm wide in the lower magnification image.

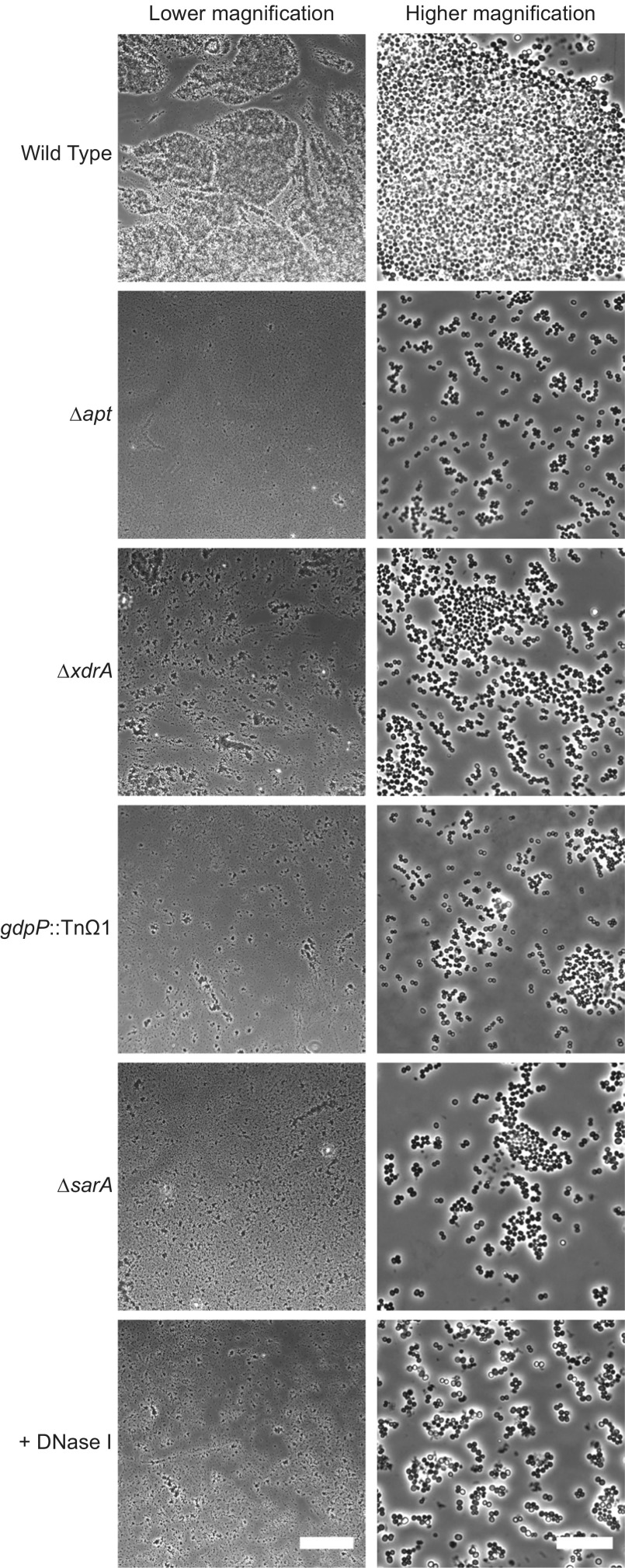

Resistance to Congo Red Is Enhanced in Mutants with Reduced eDNA.

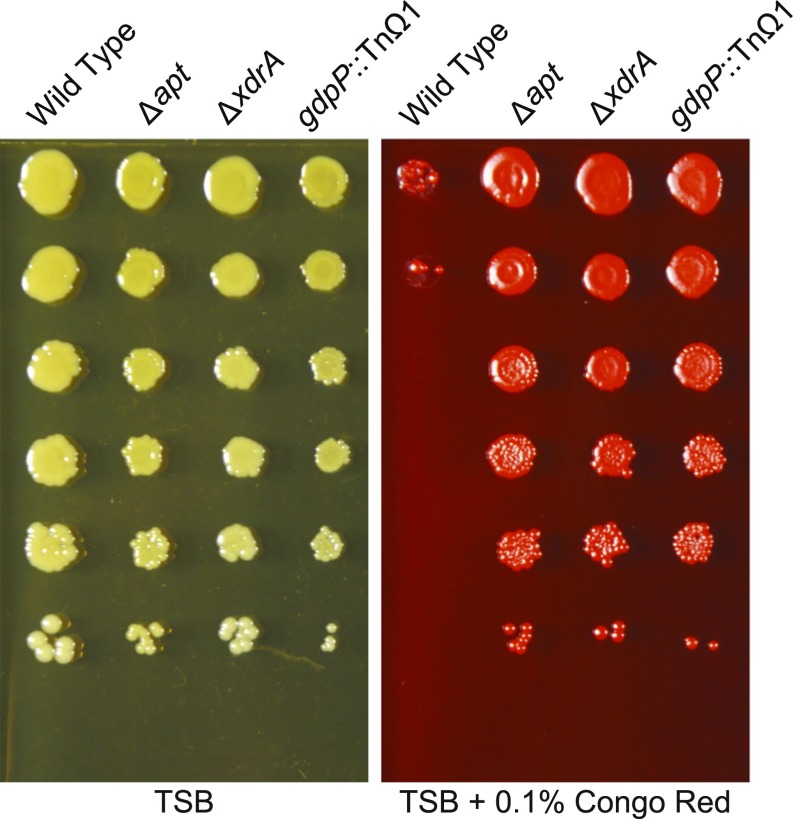

To investigate the possibility that the products of the genes identified in this study impair cell wall integrity, possibly resulting in cell lysis as a means for the release of eDNA, we investigated the sensitivity of the mutants to the dye Congo red. We found that wall teichoic acids protect S. aureus against lysis by Congo red and other dyes (23), and we reasoned that potential differences in the cell walls of eDNA-release defective mutant strains could alter Congo red susceptibility. Serial dilutions of wild-type HG003 and its mutant derivatives were spotted onto agar plates containing tryptic soy broth (TSB), with or without Congo red, and incubated overnight. Some mutants (∆spa, ∆fmtA, and ∆sarA) exhibited similar levels of sensitivity to Congo red as the wild type, or enhanced sensitivity (∆1025, ∆gidA, ∆ccpA, ∆ansA), whereas others showed a slight increase in Congo red resistance (∆yybS, ∆alsT) (Fig. S5). Interestingly, the three mutations causing the greatest defect in eDNA release (∆apt, gdpP::TnΩ1, and ∆xdrA) caused conspicuous resistance to Congo red (Fig. 4). These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that these genes, when functional, cause cell envelope alterations that impair cell wall integrity, presumably resulting in cell lysis.

Fig. S5.

Congo red phenotypes of additional mutant strains. Overnight cultures of wild-type HG003 and its mutant derivatives were serially diluted, spotted onto agar plates with or without 0.1% Congo red (A) or 0.06% Congo red (B), incubated overnight, and imaged.

Fig. 4.

Mutants with reduced eDNA display enhanced resistance to Congo red. Overnight cultures of the wild-type strain HG003 and its mutant derivatives were serially diluted, spotted onto agar plates with or without 0.1% Congo red, incubated overnight, and imaged.

The ∆gdpP mutant ANG1958 also exhibited resistance to Congo red compared with RN4220 (Fig. S2C) and in a manner that was reversed by complementation (Fig. S2D), as was the case for the gdpP::TnΩ1 strain (Fig. S3B).

Resistance to Congo Red Can Be Used To Isolate Insertions Mutations in gdpP.

The observation that certain mutants defective in eDNA release exhibited Congo red resistance provided a strategy for isolating additional mutants of the genes in this study. We determined that a Congo red concentration of 0.25% prevents growth of wild-type HG003 but allows strains with high Congo red resistance to survive. We then plated out the transposon insertion library on plates containing this high Congo red concentration and sequenced the sites of insertion by using random nested primer amplification. Among the insertions so identified were several in gdpP. One such insertion mutation, gdpP::TnΩ1, which harbored an insertion at the TA site located at codon 183 (TAC), was used in the experiments of Figs. 2–4 and Figs. S1 and S3–S6.

Fig. S6.

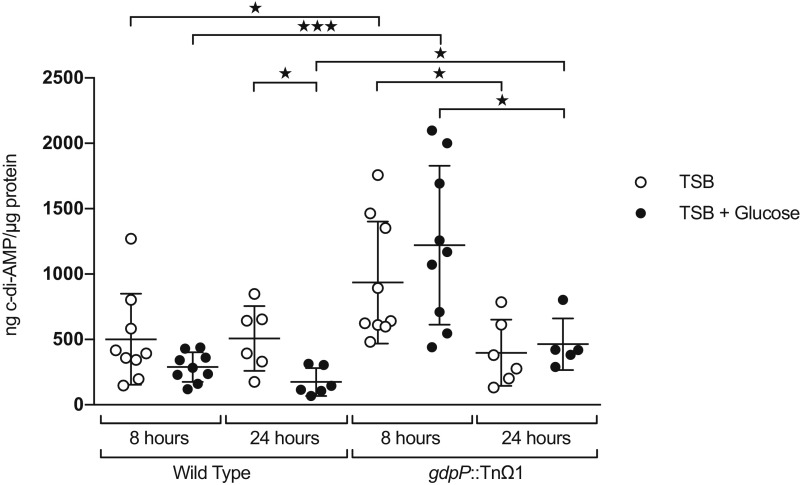

HPLC results for wild-type and gdpP::TnΩ1 strains, with and without added glucose. Biological and technical replicates of wild-type HG003 and gdpP::TnΩ1 grown in TSB with and without added glucose were analyzed for levels of cyclic-di-AMP after 8 and 24 h of growth. Significant differences were calculated with Student’s t test. ★P ≤ 0.05; ★★★P ≤ 0.001.

Growth Under Glucose Supplementation Lowers Cyclic-di-AMP Levels in a gdpP-Dependent Manner.

The discovery that gdpP is required for eDNA release prompted us to measure cyclic-di-AMP levels during biofilm formation by using HPLC. We carried out these measurements with wild-type (HG003) cells and gdpP::TnΩ1 mutant cells collected at 8 and 24 h after growth in biofilm-inducing medium that had or had not been supplemented with glucose (Fig. S6). The results show that the levels of cyclic-di-AMP were higher in wild-type cells grown in the absence of glucose or in gdpP mutant cells than in wild-type cells grown under biofilm-inducing conditions with glucose. These results together with those presented above are consistent with the hypothesis that eDNA release is triggered in part by a glucose-dependent drop in cyclic-di-AMP levels.

xdrA Influences the Expression of Genes Involved in Biofilm Formation and Virulence.

Another gene of particular interest from our genome-wide screen, xdrA, is known to encode a DNA-binding protein with an XRE-family helix-turn-helix domain that directly or indirectly activates the gene (spa) for protein A (24, 25). Given our observations that an ∆xdrA mutant is impaired in eDNA release and biofilm formation, and the fact that a ∆spa mutant was not defective in eDNA release (Fig. S2A; ref. 5), it was of interest to determine what other genes were influenced or regulated by xdrA during biofilm formation. Accordingly, we performed RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) on wild-type (HG003) cells and ∆xdrA mutant cells harvested during exponential phase in TSB medium, exponential phase in TSB adjusted to the low (5.5) pH characteristic of biofilm conditions, and early biofilm formation in TSB supplemented with glucose. We observed significant changes in transcript levels, both increases and decreases, for more than 100 genes when comparing the ∆xdrA mutant to wild-type cells. Consistent with previous reports, we saw a reduction in spa transcript levels in ∆xdrA mutant cells during exponential growth (25), and during biofilm formation and during growth at low pH. Only one other gene (the small RNA transcribed from a region downstream of SAOUHSC_00377) was similarly affected in all conditions tested. Strikingly, most of the genes that showed significant changes in transcript levels were differentially regulated under one or both of the biofilm-relevant conditions but not under conditions of exponential phase growth (Dataset S3).

To independently verify the results of RNA-seq, we performed quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) on the 11 genes whose expression was altered to the greatest extent during biofilm formation by the ∆xdrA mutation. Results of qRT-PCR confirmed the direction and magnitude of change in most cases (Table 2). Specifically, expression of spa, and an operon containing norB (which encodes an efflux pump; ref. 26), steT, ilvA, and ald, were reduced in the ∆xdrA mutant. Conversely, transcripts found in increased abundance in the deletion mutant included those encoded by the gene for δ-hemolysin (hld/RNA III); genes for the β-phenol soluble modulins (PSMβs); a putative cold shock gene, cspB; vraX, which encodes a protein that has not been well characterized but shown to be highly up-regulated during cell wall stress (27, 28); and genes for two hypothetical proteins, SAOUHSC_00560 and SAOUHSC_00141.

Table 2.

Verification of RNA-seq results by qRT-PCR

| Locus tag | Gene | Product | Fold change | |

| RNA-Seq | qRT-PCR | |||

| SAOUHSC_00069 | spa | IgG binding protein A | −41.7 | −79.4 ± 32.8 |

| SAOUHSC_01452 | ald | Alanine dehydrogenase | −32.6 | −16.1 ± 3.7 |

| SAOUHSC_01451 | ilvA | Threonine dehydratase | −21.8 | −37.7 ± 8.6 |

| SAOUHSC_01450 | steT | Amino acid permease | −16.8 | −20.3 ± 2.1 |

| SAOUHSC_01448 | norB | Drug resistance MFS transporter | −12.8 | −5.1 ± 0.1 |

| SAOUHSC_02260 | hld/ RNAIII | δ-hemolysin | 8.7 | 3.1 ± 0.2 |

| SAOUHSC_03045 | cspB | Cold shock protein | 5.8 | 1.2 ± 0.2 |

| SAOUHSC_01136 | psmβ | Phenol soluble modulin class beta | 6 | 4.9 ± 1.1 |

| SAOUHSC_00561 | vraX | Involved in cell wall stress | 5.3 | 1.8 ± 0.7 |

| SAOUHSC_00560 | — | Hypothetical protein | 4.5 | 1.2 ± 0.3 |

| SAOUHSC_00141 | — | Hypothetical protein | 6.1 | 8.5 ± 0.8 |

The ∆xdrA mutation altered the expression of several additional genes of interest. These genes include the transcriptional regulator lysR, which appeared to be down-regulated in an ∆xdrA mutant during biofilm formation, and tagG, encoding a wall teichoic acid synthesis protein, which was up-regulated. Transcripts of mgrA were also increased as measured by RNA-seq. MgrA is a regulator of autolytic activity known to directly repress norB (whose reduced transcription was also verified by qRT-PCR), and to activate abcA, a gene encoding an ATP-binding protein that confers enhanced resistance to cell wall-targeting antibiotics (29), and whose transcription was increased in the ∆xdrA mutant. Also up-regulated in the mutant strain were the genes for the α-phenol soluble modulins (PSMαs), which are cotranscribed and are located in the region between SAOUHSC_00411 and SAOUHSC_00412 (30). The agr operon was up-regulated in the ∆xdrA strain not only under biofilm-inducing conditions but also at low pH (as were the agr-regulated PSMαs, PSMβs, and RNAIII genes), increasing our confidence in this observation.

In addition to genes encoding known or suspected functions, we identified changes in the level of transcripts of several less well characterized genes (Dataset S3), including a small, noncoding RNA (sRNA), transcribed from a region downstream of SAOUHSC_00377, which is found in greater abundance in the ∆xdrA mutant when grown in all three conditions tested. The sRNA bears no extended sequence similarity to any other region of the genome (Sequence: UACAAAUUCCCGGUAACCAUUCCGGCUUCAUUCUCUUGAAGAAUGACAUAUUCUCAGCGUUUUAGCUGAAGGUCAGAUGAUACGUCAUCTGGCCUCUUUUU). It is conserved within S. aureus, but not found in other species as determined by National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) BLAST. This sRNA has been identified in previous large-scale transcriptome studies as Teg146 (31), Sau-63 (32), and JKD6008sRNA83 (33).

Discussion

The goal of this investigation was to identify genes involved in eDNA release during S. aureus biofilm formation. A challenge in identifying such genes is that eDNA becomes a community good that is shared by the population, and mutants with lesions in these genes would be predicted to be rescued by extracellular complementation. We therefore devised a strategy that allowed us to identify genes interrupted by transposon insertions, in which insertions were underrepresented in eDNA compared with gDNA contained within biofilm cells. This approach allowed us to screen a comprehensive library of transposon insertions, reasoning that mutant cells harboring such defects in eDNA externalization would be underrepresented in the eDNA recovered from the biofilm matrix (Fig. 1). The findings of this screen were then validated by showing that null mutants in genes so identified were impaired in the release of eDNA. These mutants varied widely in the extent of eDNA release impairment, with the most severely impaired mutants releasing eDNA at levels below a threshold needed for robust biofilm formation (Fig. 2). In particular, mutants of sarA, xdrA, apt, and gdpP had eDNA levels at or below those observed following DNase I treatment and were correspondingly impaired in biofilm formation. Mutation of sarA is known to cause overproduction of extracellular nucleases (19, 20), providing a simple explanation for its reduced eDNA phenotype but little insight into the mechanism governing eDNA release. The xdrA, apt, and gdpP mutations, in contrast, had little or no effect on nuclease secretion (Fig. S1), raising the possibility that one or more of these genes is directly involved in controlling eDNA release during biofilm formation.

We do not know the mechanism by which eDNA is released, but a simple possibility is that cells undergoing biofilm formation selectively lyse because of impaired cell envelope integrity, thereby releasing gDNA into the matrix. Interestingly, the mutants with the most severe reductions in eDNA release (∆xdrA, ∆apt, and gdpP::TnΩ1) exhibited enhanced resistance to Congo red (Fig. 4), which is known to induce lysis of mutants with cell envelope defects (23). Mutants that are impaired in lysis would therefore be expected to exhibit resistance to Congo red, and we speculate that the ∆xdrA, ∆apt, and gdpP::TnΩ1 mutants are defective in eDNA release because they maintain cell wall integrity under biofilm-inducing conditions. It should be noted, however, that this mechanism is evidently distinct from other known pathways of cell lysis; mutations in genes previously implicated in cell lysis [specifically ∆cidA (34), ∆aaa (35), and ∆atl (36, 37)] had little or no effect on eDNA release under our biofilm-inducing conditions (6).

The most intriguing gene to emerge from our study is gdpP, which encodes a phosphodiesterase that cleaves the second messenger cyclic-di-AMP (15). Deletion of gdpP (which elevates intracellular cyclic-di-AMP levels) has been shown to increase peptidoglycan cross-linking, enable survival without lipoteichoic acid, enhance resistance to cell envelope-targeting antibiotics, and promote acid tolerance in S. aureus (15, 38). High levels of cyclic-di-AMP have been linked to increased transcript levels of pbp4, a penicillin binding protein, which could explain the increase in peptidoglycan cross-linking (39). In B. subtilis, cyclic-di-AMP plays a role in peptidoglycan homeostasis and its depletion promotes cell lysis (40), suggesting that regulation of wall integrity may be a broadly conserved role for cyclic-di-AMP. Together with the findings of our investigation, this prior work suggests a model in which cyclic-di-AMP levels drop under biofilm-inducing conditions, impairing cell wall integrity and triggering cell lysis. In support of this model, we have shown that growth under glucose supplementation lowers cyclic-di-AMP levels and that a gdpP mutation leads to increased levels of the second messenger.

Our model offers a possible explanation for the role of apt, which encodes a purine salvage enzyme, adenine phosphoribosyltransferase. Deletion of apt (or of purR, also identified in our screen) would enhance de novo purine nucleotide synthesis, conceivably preventing the drop in cyclic-di-AMP levels. It will be interesting to see whether and how ∆apt influences cyclic-di-AMP levels under biofilm-inducing conditions.

Also of special interest is xdrA, which encodes a DNA-binding protein that binds the methicillin resistance mecA promoter region (24). Deletion of xdrA is known to increase resistance in several methicillin-resistant clinical isolates. Using RNA-seq, we found that deletion of xdrA increased expression of the agr quorum sensing system and the downstream PSM genes, which have been linked both to biofilm dispersal and stability (41–43). We also found higher expression levels of genes involved in cell envelope synthesis and stress response. It could be that the ∆xdrA strain induces the cell wall stress stimulon, as evidenced by higher vraX levels (27, 28), which in turn contributes to increased cell envelope strength and reduced lysis and, hence, reduced eDNA.

Interestingly, an sRNA was also found to be highly overexpressed in the ∆xdrA mutant. This sRNA has been found to show altered expression in a small colony variant of S. aureus isolated from a chronic osteomyelitis infection (32). Small colony variants of S. aureus have been found to have thick cell walls (44, 45), and this sRNA could additionally contribute to the reduced lysis phenotype we observe in ∆xdrA.

Together, our analysis identified xdrA as a transcriptional regulator that directly or indirectly modulates the expression of genes that control cell wall stability, quorum sensing, and biofilm dispersal under biofilm-inducing conditions. It will be of interest to see which genes under XdrA control are needed for eDNA release and whether they act upstream, downstream, or independently of cyclic-di-AMP.

In sum, we have identified previously unrecognized genes that contribute to eDNA release and biofilm formation. Our results implicate a reduction in cyclic-di-AMP levels in triggering eDNA release via impaired cell wall homoeostasis. The products of the genes that we have identified provide potential targets for future therapies designed to dissociate or prevent the formation of staphylococcal biofilms. Also, our strategy of identifying genes in which transposon insertions are underrepresented into eDNA could be applicable to identifying genes involved in the release of extracellular DNA in other biofilm-forming bacteria.

Materials and Methods

Strains and Growth Conditions.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table S1. S. aureus was maintained in tryptic soy broth (TSB; EMD Millipore) and on LB agar (BD). S. aureus biofilms were grown in TSB supplemented with 0.5% glucose (TSB-G). Escherichia coli DC10B was maintained in LB and on LB agar. Selection for drug-resistant strains was carried out by using 3 μg/mL tetracycline, 10 μg/mL erythromycin, or 10 μg/mL chloramphenicol for S. aureus, and 100 μg/mL ampicillin for E. coli.

Table S1.

Bacterial strains used in this work

| Name | Strain background | Genotype/description | Source |

| DC10B | E. coli DH10B | ∆dcm | 49 |

| HG003 | S. aureus NCTC 8325 (RN1) | agr+ tcaR+ rsbU+ | 4 |

| RN4220 | S. aureus NCTC8325-4 | Restriction-deficient derivative of NCTC 8325–4, agr tcaR rsbU, cured of three prophages | 55 |

| ANG1958/ SEJ1∆gdpP::kan | RN4220 | ∆SAOUHSC_00069 (∆spa) ∆SAOUHSC_00015 (∆gdpP)::kan | 15 |

| LCF78 | HG003 | ∆SAOUHSC_00069 (∆spa) | 5 |

| LCF48 | HG003 | ∆SAOUHSC_00620 (∆sarA) | 6 |

| ASD670 | HG003 | ∆SAOUHSC_00014 (∆yybS) | This study |

| ASD744 | HG003 | gdpP::TnΩ1 | This study |

| ASD464 | HG003 | ∆SAOUHSC_00998 (∆fmtA) | This study |

| ASD676 | HG003 | ∆SAOUHSC_01025 | This study |

| ASD465 | HG003 | ∆SAOUHSC_01354 (∆alsT) | This study |

| ASD672 | HG003 | ∆SAOUHSC_01497 (∆ansA) | This study |

| ASD466 | HG003 | ∆SAOUHSC_01743 (∆apt) | This study |

| ASD673 | HG003 | ∆SAOUHSC_01850 (∆ccpA) | This study |

| ASD448 | HG003 | ∆SAOUHSC_01979 (∆xdrA) | This study |

| ASD671 | HG003 | ∆SAOUHSC_03052 (∆gidA) | This study |

| ASD686 | ANG1958/ SEJ1∆gdpP::kan | + gdpP complementation construct pASD135 | This study |

| ASD696 | RN4220 | + gdpP complementation construct pASD135 | This study |

| ASD717 | ANG1958/ SEJ1∆gdpP::kan | + vector pASD145 | This study |

| ASD718 | RN4220 | + vector pASD145 | This study |

| ASD748 | gdpP::TnΩ1 | + gdpP complementation construct pASD133 | This study |

| ASD751 | HG003 | + gdpP complementation construct pASD133 | This study |

| ASD749 | gdpP::TnΩ1 | + vector pASD132 | This study |

| ASD734 | HG003 | + vector pASD132 | This study |

Transposon-Insertion Screen.

The transposon insertion experiment was performed by using an ultra-high density library in the HG003 strain background (11). A frozen aliquot of the library was added to a small volume of TSB. After 1 h of growth at 37 °C, this preculture was used to inoculate fresh TSB-G to an OD600 of 0.01. Three hundred milliliters of this culture was added to large volume dishes (no. 166508; ThermoFisher) and incubated statically at 37 °C for 6 or 8 h. The medium was aspirated, and the remaining adherent cells were resuspended in PBS at pH 7.5 by using pipetting and cell scrapers. Following a brief incubation in PBS, biofilm cells were pelleted by centrifugation for 10 min at 7,000 × g at 4 °C, and the supernatant was removed and filtered by using an Acrodisc 25-mm syringe filter with 0.2-μm HT Tuffryn membrane (PN 4192, Pall) or using a 0.22-μm filter system (431098, Corning). gDNA from the biofilm cells was extracted from the pelleted biofilm cells by using the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (A1120m Promega). eDNA from the matrix was precipitated from the supernatant by adding 1/10 of the supernatant volume of 3 M NaOAc at pH 5.0 and isopropanol to a final concentration of 30%. This mixture was incubated overnight at −20 °C and centrifuged for 15 min at 24,000 × g at 4 °C. The pellet was washed with 75% ice cold ethanol, air dried, and resuspended in 400 μL of water. Extracted eDNA and gDNA were then RNase treated by using 1 U RNase H (Roche) per ∼50 μg of gDNA or 5 μg of eDNA for 15 min at 37 °C. The DNAs were purified by extraction with phenol-chloroform and run over a DNA purification column (D4065, Zymo Research) according to manufacturer’s guidelines. Sample preparation for next generation sequencing and mapping of reads to TA sites were performed as described (11). Sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSEq 2500 at the Tufts University Core Facility.

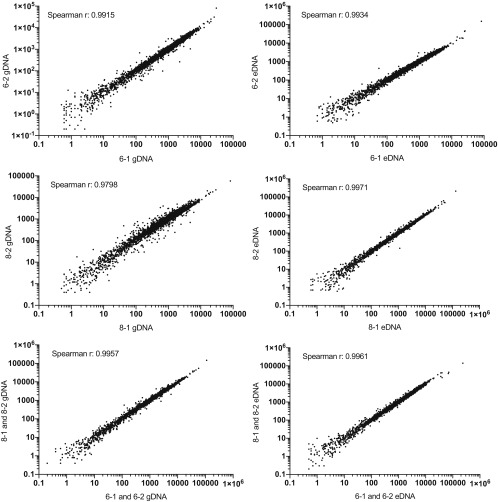

Sequence Analysis.

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were calculated by using read count per gene for the different replicates and time points (Fig. S7). Our final analysis compared results from 6-h and 8-h time points in combination, because we expected that eDNA release was occurring throughout this time period and wanted to capture any relevant genes, even those with a mild or delayed defect in eDNA release and to have enough insertions to calculate significance even in genes with few TA sites. Analysis of the transposon-sequencing data were performed by using TRANSIT (46). Resampling comparative analysis of eDNA to gDNA samples was performed with 10,000 permutations by using trimmed total reads normalization and LOESS genome positional bias correction. Genes of interest were identified as those with a log2-fold change of less than or equal to −1, a false discovery rate of less than 5% (q < 0.05), and a (number of normalized transposon counts)/(TA sites hit) greater than 1 for the count average across eDNA and gDNA. Because the library consisted of six transposon constructs, we ran our analysis on four promoter categories: all (all transposons), blunt (promoterless), Perm (weakest promoter), and other (outward-facing promoters) (11).

Fig. S7.

Correlation of replicates for transposon insertion experiment. Biological replicates for 6- and 8-h time points were compared for both biofilm gDNA and eDNA. In addition, 6-h samples were compared with 8-h samples. For each comparison, the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was calculated.

Strain Construction.

Strain SEJ1 gdpP::kan (ANG1958) was constructed in an RN4220 ∆spa background (15). Construction of unmarked deletion mutants in HG003 was performed essentially as described (6) by using pKFC or pKFT vectors (47). Plasmids pASD132 and pASD145 (empty vectors) were generated by using isothermal assembly of pCM29 (48) amplified with ASD226F and ASD226R-2 (for pASD132), or pAH9 (41) amplified by using ASD234F and ASD229R (for pASD145), to remove the fluorescent reporters. Plasmids pASD135 and pASD133 (gdpP complementation constructs) were generated by using isothermal assembly of the gdpP gene, the upstream gene, and their native promoter with a backbone. For both, gdpP was amplified with primers ASD227F-1 and ASD227R-1. For pASD133, the backbone was pCM29 digested with PstI and EcoRI, and for pASD135, the backbone was pAH9 amplified with ASD230F and ASD230R. Initial transformation of isothermal assembly products was done in E. coli DC10B (49). Plasmid sequences were confirmed and plasmids were transformed directly into HG003 with appropriate selection. See Table S2 for deletion construct details and Table S3 for primer sequences.

Table S2.

Deletion mutant construction details

| Strain | Background strain | Deleted gene | Construct | Primers (upstream flank) | Primers (downstream flank) | Primers (confirmation of construct) | Primers (confirmation in genome) |

| ASD670 | HG003 | ∆SAOUHSC_00014 (∆yybS) | pASD112 | ASD194_1, ASD194_2 | ASD194_3, ASD194_4 | LF019F, LF019R, ASD194_7, ASD194_8 | ASD194_5, ASD194_6 |

| ASD464 | HG003 | ∆SAOUHSC_00998 (∆fmtA) | pASD064 | ASD145_1, ASD145_2 | ASD145_3, ASD145_4 | LF019F, LF019R, ASD145_7, ASD145_8 | ASD145_5, ASD145_6 |

| ASD676 | HG003 | ∆SAOUHSC_01025 | pASD114 | ASD196_1, ASD196_2 | ASD196_3, ASD196_4 | LF019F, LF019R, ASD196_7, ASD196_8 | ASD196_5, ASD196_6 |

| ASD465 | HG003 | ∆SAOUHSC_01354 (∆alsT) | pASD065 | ASD146_1, ASD146_2 | ASD146_3, ASD146_4 | LF019F, LF019R, ASD148_7, ASD146_8 | ASD148_5, ASD146_6 |

| ASD672 | HG003 | ∆SAOUHSC_01497 (∆ansA) | pASD120 | ASD202_1, ASD202_2 | ASD202_3, ASD202_4 | LF019F, LF019R, ASD202_7, ASD202_8 | ASD202_5, ASD202_6 |

| ASD466 | HG003 | ∆SAOUHSC_01743 (∆apt) | pASD066 | ASD147_1, ASD147_2 | ASD147_3, ASD147_4 | LF019F, LF019R, ASD147_7, ASD147_8 | ASD147_5, ASD147_6 |

| ASD673 | HG003 | ∆SAOUHSC_01850 (∆ccpA) | pASD125 | ASD207_1, ASD207_2 | ASD207_3, ASD207_4 | LF019F, LF019R, ASD207_7, ASD207_8 | ASD207_5, ASD207_6 |

| ASD448 | HG003 | ∆SAOUHSC_01979 (∆xdrA) | pNMd1979 | 1979-P1, 1979-P2 | 1979-P3, 1979-P4 | LF019F, LF019R, 1979-P5 1979-P6 | 1979-P7, 1979-P8 |

| ASD671 | HG003 | ∆SAOUHSC_03052 (∆gidA) | pASD117 | ASD199_1, ASD199_2 | ASD199_3, ASD199_4 | LF019F, LF019R, ASD199_7, ASD199_8 | ASD199_5, ASD199_6 |

Table S3.

Primers table

| Purpose | Relevant gene | Primer Name | Primer Sequence |

| Strain construction | SAOUHSC_00014 (yybS) | ASD194_1 | TTGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTGAATTCTGATGTTATTGGTAGTCCTTTCGG |

| ASD194_2 | CCGATTCATTATTCCACCTCTATATTTTTAACTATAGCTATTATTTTAACCTCTTTAAT | ||

| ASD194_3 | ATAGAGGTGGAATAATGAATCGGC | ||

| ASD194_4 | GTCGACTCTAGAGGATCCCCGGGCTTTGTCACCCTCTGCAAGG | ||

| ASD194_5 | TGAGCATGTCGGTTATCATGG | ||

| ASD194_6 | ACGCGTCGTAATGTTGGATC | ||

| ASD194_7 | CGTGCCTGATAATGTTGGGC | ||

| ASD194_8 | TGGTTAACCCATTCGATGTGATC | ||

| SAOUHSC_00998 (fmtA) | ASD145_1 | TTGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTGAATTCGCAACTGCTAAAGCCTCATCAC | |

| ASD145_2 | TGTTATATCTTCTATATTAATTGATAATTGCCTCACAATGTATTCATTTTATATATTTAAATCG | ||

| ASD145_3 | CATTGTGAGGCAATTATCAATTAATATAGAAGATATAACATGTATATGGCATTAAG | ||

| ASD145_4 | GTCGACTCTAGAGGATCCCCGGGTGCATCAGAAGGCGTTAACCC | ||

| ASD145_5 | ATCAACTTCCTGTGCTTTTTGG | ||

| ASD145_6 | AACTTTGCAACATGGTGGCG | ||

| ASD145_7 | ACAAATGTTATGTCAAAGTTCCTTG | ||

| ASD145_8 | ACGCATGGACCAACGTATTCG | ||

| SAOUHSC_01025 | ASD196_1 | TTGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTGAATTCGATAGCAGACAATCGCTGCC | |

| ASD196_2 | AATGTTTAATAGATAGTACTTTTATAATGCTTTTAATATGTTCACCTCAAAATCATTATATATTAATCT | ||

| ASD196_3 | TTAAAAGCATTATAAAAGTACTATCTATTAAACATT | ||

| ASD196_4 | GTCGACTCTAGAGGATCCCCGGGCCCTTAATTTCTTGCGCACTTC | ||

| ASD196_5 | AATGATAGTTTCGCCGGCAC | ||

| ASD196_6 | GAAGATGCCTCACTTGCTGC | ||

| ASD196_7 | AGGAGAGGGATACATGCGC | ||

| ASD196_8 | CGCAAATTCCATAAGTCGCTTC | ||

| SAOUHSC_01354 (alsT) | ASD146_1 | TTGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTGAATTCGTGACAGTTTACTTAAACATCAAGAAG | |

| ASD146_2 | AATCGTTACATTAAAAATATAATAAACCCCTCGCATCCTCTAC | ||

| ASD146_3 | GAGGATGCGAGGGGTTTATTATATTTTTAATGTAACGATTCATTATATAAAAATCAAATAAACCC | ||

| ASD146_4 | GTCGACTCTAGAGGATCCCCGGGTTGATCAAGGTCATCTCATGC | ||

| ASD148_5 | ACATAGTTGCGCTTGAAGGTG | ||

| ASD146_6 | TACAGTAACGAAACGCCCGTG | ||

| ASD148_7 | CACATCGTATTGTAGCTGCACATG | ||

| ASD146_8 | TCGCTTTAATTTGAAAACCTCAGGG | ||

| SAOUHSC_01497 (ansA) | ASD202_1 | TTGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTGAATTCTGTGACTAAATCAGCTTCTTTTGC | |

| ASD202_2 | GTACATAGACCTTTTTATGTTACGTATTCAATATTTCCTCCTATATTTAATTTACCTAATTATGA | ||

| ASD202_3 | TGAATACGTAACATAAAAAGGTCTATGTAC | ||

| ASD202_4 | GTCGACTCTAGAGGATCCCCGGGCCATGCGGATTAAGTG | ||

| ASD202_5 | AAAGCCACGCAAATAAGCAAC | ||

| ASD202_6 | AAAGGAGGCCGAAACAATGC | ||

| ASD202_7 | GGTCAACTAGTTTTGCAAAGTCC | ||

| ASD202_8 | CAGGTGTAATTGCTGCAGGG | ||

| SAOUHSC_01743 (apt) | ASD147_1 | TTGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTGAATTCGCCGTTTCGATATACGCTTCAC | |

| ASD147_2 | CAATTTAGGAGGAAATATTATAAATAATATAATTTTATCAAATGAAATCCTTCATCAAATGTATAAGAACC | ||

| ASD147_3 | TGATAAAATTATATTATTTATAATATTTCCTCCTAAATTGCTCACGAC | ||

| ASD147_4 | GTCGACTCTAGAGGATCCCCGGGGGCTGCAGGTATGACGATGG | ||

| ASD147_5 | TGCACCAACCCAAGTATCGC | ||

| ASD147_6 | AATCATGCAAAAGGCTCCGC | ||

| ASD147_7 | CCGTCGACGATAAATATTTATCCTGTC | ||

| ASD147_8 | AAGATCGATTGATTCCAGCAAAG | ||

| SAOUHSC_01850 (ccpA) | ASD207_1 | TTGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTGAATTCGCTTCACATGGCATTATCAGTG | |

| ASD207_2 | GAATAAAACGTTTACAAGGAGGAAATTATTCACAAAATTAGGCATTCATCTAACG | ||

| ASD207_3 | AATTTCCTCCTTGTAAACGTTTTATTC | ||

| ASD207_4 | GTCGACTCTAGAGGATCCCCGGGTAAAAGAAGCTGGCCGTACG | ||

| ASD207_5 | ACCTAGAATTGCAACAGATGACG | ||

| ASD207_6 | AGGCCTAGGTGTTGAAGGAC | ||

| ASD207_7 | TTGGAGAGTCGTACCACGTG | ||

| ASD207_8 | GATTCACACATTTGTTGCTGAAATG | ||

| SAOUHSC_01979 (xdrA) | 1979-P1 | ACGGCCAGTGAATTCGAGCTCGGTACCCGGGGATCCTCGCTTGTTTGCTTGCATATGT | |

| 1979-P2 | CAAACAGAAAGGTAGATAACAGATCTAGGCCTATATACTTTTAATAAATA | ||

| 1979-P3 | TATTTATTAAAAGTATATAGGCCTAGATCTGTTATCTACCTTTCTGTTTG | ||

| 1979-P4 | AGGAAACAGCTATGACCATGATTACGCCAAGCTTATTGTGCGACAAGGATTGCGAT | ||

| 1979-P5 | TGACTCCTTTGTGACAACAT | ||

| 1979-P6 | TCAAATCTAGTGATTATGCAT | ||

| 1979-P7 | TGCTAATTTGCTAGAGAGTTGA | ||

| 1979-P8 | TCAGCCAACAAAGGGTACACA | ||

| SAOUHSC_03052 (gidA) | ASD199_1 | TTGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTGAATTCTCTAAATCGGCGCTCTCCAG | |

| ASD199_2 | GCTAGTAAGATATCAAATAAGGAGGTTTATATTATGACTGTAGAATGGTTAGCAGAAC | ||

| ASD199_3 | AATATAAACCTCCTTATTTGATATCTTACTAGC | ||

| ASD199_4 | GTCGACTCTAGAGGATCCCCGGGTCGCTCGAAGACAGATAGAGC | ||

| ASD199_5 | GCAACAACAGCCGTCTCTTC | ||

| ASD199_6 | ACATATGGCGCTAGAATGGC | ||

| ASD199_7 | ACGGAATACTTGGAAAACCAGC | ||

| ASD199_8 | TCGAGATTTGTTCTTTGGTGGAG | ||

| Plasmid construction | ASD226R-2 | AACAGCTATGACATGATTACGAATTTGCAGGCATGCAAGCTTTTAAAAAGCAAATATGAG | |

| ASD226F | TGCAGGCATGCAAGCTTTTAAAAAGCAAATATGAGCC | ||

| ASD227F-1 | TTTTTAAAAGCTTGCATGCCTGCAGCGTGCCTGATAATGTTGGGC | ||

| ASD227R-1 | AACAGCTATGACATGATTACGAATTCACTGGTACTTCTTTAACTTCACC | ||

| ASD229R | GAATTCACTGGCCGTCGTTTTACAAC | ||

| ASD230F | GAATTCGTAATCATGTCATAGCTGTTGTCATAGCTGTTTCCTGTGTG | ||

| ASD230R | CTGCAGGCATGCAAGCTTTTAAAAACACTGGCCGTCGTTTTACAAC | ||

| ASD234F | GTTGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTGAATTCGTCATAGCTGTTTCCTGTGTG | ||

| qRT-PCR | SAOUHSC_00069 (spa) | spa-F3 | TCAATTCGTAAACTAGGTGTAGGTATTGCA |

| spa-R3 | CAGCATTTGCAGCAGGTGTTA | ||

| SAOUHSC_00141 | yrhF-F | AGATCTTATCGTAAAGAATACGTGGGT | |

| yrhF-R | TCAACTTTACTCAAAACACCTGTCATAT | ||

| SAOUHSC_00560 | 560-F | TCGTAAATGA TGATAATCCAATACATAATGA | |

| 560-R | ATTTGACACTGGTTTGTCTCTAATGA | ||

| SAOUHSC_00561 (vraX) | vraX-F | GCGCACCAGTTTATGAAATTATAACCA | |

| vraX-R | ATCGTCTTGTAATAAAGAGAGCAATTTGA | ||

| SAOUHSC_01136 | 1136-F | ATGACTGGACTAGCAGAAGCAAT | |

| 1136-R | TACCTAGTAAACCCACACCGTTA | ||

| SAOUHSC_01448 (norB) | norB-F | AGGCACACCTGAAACTAAATCTAAAT | |

| norB-R | GTTACACCTAATTCTGATCCTTTAGT | ||

| SAOUHSC_01450 | 1450-F | TCCAGCTAACGTAGCAGCATTGT | |

| 1450-R | AGATGCGATTGCTATTGGTATTAACGA | ||

| SAOUHSC_01451 (ilvA) | ilvA-F | AAGGCATTATCGCAGCATCTGCT | |

| ilvA-R | TCAGGCATTACAATCGTTGCATCA | ||

| SAOUHSC_01452 (ald) | ald-F | ACTACTCTGAAGCACAACATGGT | |

| ald-R | TGCTGCTACTCCACCACCGA | ||

| SAOUHSC_01490 (hu) | hu-F | TTTACGTGCAGCACGTTCAC | |

| hu-R | AAAAAGAAGCTGGTTCAGCAGTAG | ||

| SAOUHSC_02260 (hld) | hid-F | ATTAAGGAAGGAGTGATTTCAATGGCA | |

| hid-R | TGAATTTGTTCACTGTGTCGATAATC | ||

| SAOUHSC_03045 (cspB) | cspB-F | AGGTTTTCTATATGAATAACGGTACAGTA | |

| cspB-R | TGTACGAATACGTCTCCGCCAT | ||

| Transposon mapping | Rnd1-ARB1 | GGCCACGCGTCGACTAGTACNNNNNNNNNNAGAG | |

| Rnd1-ARB2 | GGCCACGCGTCGACTAGTACNNNNNNNNNNACGCC | ||

| Rnd1-ARB3 | GGCCACGCGTCGACTAGTACNNNNNNNNNNGATAT | ||

| ASD249 Rnd1-Tn | ATGTAGTTACTCTCAATATAGACCGG | ||

| Rnd2-ARB | GGCCACGCGTCGACTAGTAC | ||

| ASD251 Rnd2-Tn | GGGGACTTATCATCCAACCTG | ||

| ASD252 | GGCATACGAAGACCACGC |

Quantitative Biofilm Assay.

Overnight cultures of S. aureus were grown in TSB and diluted 1:1,000 into fresh TSB-G. For strains containing pASD135 or pASD145, erythromycin was included. For strains containing pASD132 or pASD133, chloramphenicol was included. Two hundred-microliter aliquots of this inoculum were added in triplicate to wells of a Nunc MicroWell 96-well plate (no. 167008; ThermoFisher) and incubated statically at 37 °C for 24 h. The medium was then carefully removed, and biofilms were washed twice with 100 μL of PBS at pH 7.5. The washed biofilms were then resuspended in 200 μL of PBS at pH 7.5. The OD600 of these three fractions was then measured by using a Bio-Tek Synergy II plate reader (BioTek Instruments). Values from noninoculated wells with TSB-G or PBS alone were subtracted from inoculated well readings, and averages and SDs calculated. All biofilm assays were performed in triplicate a minimum of three times.

Quantitative eDNA Measurement.

Cells in 200 μL of biofilm-inducing medium were grown as described above, and the resuspended biofilm cells (following the wash step) were filtered by using 0.2-μm AcroPrep Advance 96-well filter plates (no. 8019; Pall). To measure eDNA, 100 μL of the filtered resuspension was then mixed with 100 μL of 2 μM SYTOX Green (no. S7020; ThermoFisher) solution in PBS to a final concentration of 1 μM in 200 μL (50). Fluorescence was measured by using a plate reader (Infinite 200 Pro, Tecan) with excitation and emission wavelengths of 465 nm and 510 nm, respectively, and the amount of eDNA present relative to wild-type HG003 was calculated.

DNase Test Agar Plating.

Overnight cultures were grown in TSB, and 10-μL aliquots were spotted onto DNase test agar plates (no. 263220; Difco). Plates were incubated at 37 °C overnight, flooded with 1 M HCl, and imaged.

Visualizing Cell Clumping.

Preparation of samples was performed as described (6). Following the centrifugation step to concentrate cells, pellets were imaged. Wild-type, DNase I-treated, and mutant cells were resuspended by using the same number of pipetting steps. Higher magnification images were taken with an Olympus BX61 microscope by using a 100×/1.3 N.A. objective, whereas lower magnification images were taken with a Leica DM5500 B microscope by using a 10×/0.3 N.A. objective.

Congo Red Assay.

Congo red susceptibility assays were performed by spotting 10-fold dilutions of overnight cultures onto TSB agar and TSB agar supplemented with 0.1% or 0.06% (wt/vol) Congo red, as indicated. For strains containing pASD135 or pASD145, erythromycin was included. For strains containing pASD132 or pASD133, chloramphenicol was included. Plates were incubated at 37 °C overnight and imaged.

Congo Red-Resistant Mutant Isolation.

Dilutions of the transposon insertion library from the initial transposon insertion screen were plated onto TSB agar supplemented with 0.25% (wt/vol) Congo red. Resistant mutants were isolated, and sites of insertion were determined by using random nested primer amplification with Rnd1 primers followed by Rnd2 primers, followed by sequencing (51). The specific site of insertion was determined by sequencing a PCR product amplified by using a gene-specific primer (ASD227-R-1) and a transposon-specific primer (ASD252). See Table S3 for primer sequences.

RNA Isolation.

Dilutions of overnight cultures (1:1,000) were used as the inoculum for all samples. Exponential-phase cultures were grown in shaking conditions at 37 °C to an OD600 of 0.5 in either TSB or TSB adjusted to pH 5.5. Biofilms were grown in static conditions at 37 °C in TSB-G for 6 h, medium was then removed and biofilm cells were scraped off in PBS without a wash step. Samples were collected by using the RNAprotect Bacteria Reagent (no. 76506; Qiagen) and snap frozen. RNA was isolated by adding 1 mL of TRIzol reagent (no. 1559026, ThermoFisher) to each sample and lysing cells by using a FastPrep (MP Biomedicals) for three 1-min pulses with 2- to 3-min incubations on ice in between. After lysis, 200 μL of chloroform was added to each sample, samples were vortexed for 1 min, incubated for 5 min at room temperature and centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 5 min. The top phase was then collected, 500 μL of isopropanol was added to it, samples were mixed by inverting, incubated 10 min at room temperature, and centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. Pellets were than washed with 500 μL of 75% ethanol, centrifuged at 18,000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C, and pellets were air dried and resuspended in 150 μL of water. These samples were then treated with DNase I (04716728001; Roche) according to manufacturer’s guidelines and purified by using the RNeasy RNA cleanup protocol (Qiagen).

RNA-Seq Library Preparation.

Throughout, RNA was either precipitated with 50% isopropanol, 150 mM sodium acetate pH 5.5, and 30 μg of GlycoBlue Coprecipitant (ThermoFisher) for 30 min at −80 °C or cleaned by using a Zymogen RNA Clean & Concentrator-5 as indicated, and RNA was excised from polyacrylamide gels by using the ZR small-RNA PAGE recovery kit (Zymogen). Samples for denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis were prepared by using Novex-TBE-Urea sample buffer (Life Technologies) and treated for 2 min at 80 °C.

For the sequencing library, total RNA (5–10 μg) was depleted of rRNA by using MICROBExpress (ThermoFisher). RNA depleted of rRNA was precipitated and resuspended into 40 μL of 10 mM Tris⋅HCl at pH 8.0. The RNA was fragmented by first heating the sample to 95 °C for 2 min and adding RNA fragmentation buffer (1×, ThermoFisher) for 1 min at 95 °C and quenched by adding RNA fragmentation stop buffer (ThermoFisher). Fragmented RNAs between 20 and 40 bp were isolated by size excision from a denaturing polyacrylamide gel (15%, TBE-Urea, 65 min., 200 V, Life Technologies). Size-selected fragments were dephosphorylated by using T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs), cleaned up, and ligated to 5′ adenylated and 3′-end blocked linker 1 (/5rApp/CTGTAGGCACCATCAAT/3ddc, IDT) by using T4 RNA ligase 2, truncated K227Q (New England Biolabs). The ligation was carried out at 25 °C for 2.5 h by using 5 pmol of dephosphorylated RNA in the presence of 25% PEG 8000 and Superase-In (ThermoFisher). Ligation products from 35 to 65 bp were excised after denaturing PAGE (10% TBE-Urea, 50 min, 200 V, Life Technologies). cDNA was prepared by reverse transcription of ligated RNA by using SuperScript III (Life Technologies) at 50 °C for 30 min with primer oCJ485 (/5Phos/AGATCGGAAGAGCGTCGTGTAGGGAAAGAGTGT/iSp18/CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATATTGATGGT, IDT) and isolated by size excision (10% TBE-Urea, 200 V, 80 min, Life Technologies). Single-stranded cDNA was circularized by using CircLigase (Illumina) at 60 °C for 2 h. cDNA was amplified by using Phusion DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) with primer o231 (CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGA, IDT) and indexing primer (AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCGGAAGAGCACACGTCTGAACTCCAGTCACNNNNNNCGACAGGTTCAGAGTTC, IDT). After 6–10 rounds of PCR amplification, the product was selected by size from a nondenaturing PAGE (8% TB, 45 min, 180 V, Life Technologies).

RNA-Seq and Data Analysis.

Sequencing was performed at the MIT BioMicro Center on a HiSEq 2000 with 50-bp single-end reads. FASTQ files of sequence data were processed by removing linker sequence, demultiplexing, and mapping to the NCTC 8325 genome (NCBI Reference Sequence: NC_007795.1) by using bowtie. The resulting SAM files were then imported into Geneious (in all cases, v. 9.0.5 was used), where expression levels were calculated. Identification of differentially expressed genes was also performed within Geneious, where transcripts were normalized by total count excluding upper quartile. This normalization method was chosen because of the variability in rRNA depletion from sample to sample. We used a cutoff of an absolute log2-fold change of greater than 1.5 and a confidence value of 10 or above (This value represents the negative log10 of the P value).

qRT-PCR.

cDNA was synthesized with 5 μg of RNA after DNase I treatment (see above) by using random hexamers (ThermoFisher) and SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (RT; Life Technologies) according to manufacturer’s guidelines. In negative control reactions, RT was omitted. Only samples with at least 10 cycles difference between samples with and without RT were analyzed. qRT-PCR was performed by using SYBR FAST Universal One-Step qRT-PCR Kit (KAPA Biosystems) with initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, 40 cycles: 95 °C for 15 s, 53 °C for 15 s, 72 °C for 20 s followed by melting curve analysis with 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 15 s, and a final temperature increase to 95 °C over 10 min. Primer pairs for genes tested are listed in Table S3. Data analysis was performed according to Pfaffl (52), with hu used for normalization (53).

HPLC.

Overnight cultures of S. aureus were grown in TSB and diluted 1:1,000 into fresh TSB or TSB-G. Cultures were grown with shaking at 37 °C for the durations indicated, and samples were prepared for analysis as described for c-di-GMP (54). Briefly, cell pellets were washed twice with cold molecular grade water (Corning). Cell pellets were then resuspended in 50 μL of molecular grade water containing 100 pg of c-di-GMP (used as an internal standard). Cells were lysed by using 14.1 μL of cold 70% perchloric acid (Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated on ice for 30 min. After incubation, the samples were centrifuged at 21,000 × g for 5 min. Supernatants were removed and neutralized with 32.8 μL of 2.5 M KHCO3 (Sigma Aldrich), whereas pellets were washed with acetone and used later for protein analysis. Once neutralized, samples were centrifuged at 21,000 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was then removed and stored at −80 °C until HPLC analysis. cyclic-di-AMP and ci-di-GMP standards (Sigma-Aldrich) were treated the same as the samples. Samples were run similar to c-di-GMP (51) on an Agilent 1100 HPLC-UV and peaks were quantified at 260 nm. Separation was carried out by using a reverse-phase C18 Targa column (2.1 × 40 mm; 5 μm) with a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min by using the following buffers and gradient: buffer A (10 mM of ammonium acetate in water) and buffer B (10 mM of ammonium acetate in methanol) for 0–9 min (99% buffer A, 1% buffer B), 9–14 min (15% buffer B), 14–19 min (25% buffer B), 19–26 min (90% buffer B), and 26–40 min (1% buffer B). Protein pellets were resuspended in 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 6 M urea, 0.05% SDS, and measured by using a BCA kit (Pierce). cyclic-di-AMP levels were normalized to protein amount.

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 7. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t tests were performed, and the levels of significance are indicated in the figure legends.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Gründling for strain ANG1958, MIT BioMicro Center for RNA-seq work, the Harvard Bauer Core for HPLC access, the Tufts University Core Facility for sequencing work and for access to their Galaxy server, and L. Foulston and V. Dengler for advice on the manuscript. Funding for this work was provided by NIH Grant P01-AI083214, an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Program Fellowship (to A.S.D.), by the Searle Scholars Program and the Sloan Research Fellowship (to G-W L.), and NIH Grant GM18568 (to R.L.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1704544114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Conlon BP. Staphylococcus aureus chronic and relapsing infections: Evidence of a role for persister cells: An investigation of persister cells, their formation and their role in S. aureus disease. BioEssays. 2014;36:991–996. doi: 10.1002/bies.201400080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stewart PS. 2015. Antimicrobial tolerance in biofilms. Microbiol Spectr 3, 10.1128/microbiolspec.MB-0010-2014.

- 3.McCarthy H, et al. Methicillin resistance and the biofilm phenotype in Staphylococcus aureus. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2015;5:1. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2015.00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herbert S, et al. Repair of global regulators in Staphylococcus aureus 8325 and comparative analysis with other clinical isolates. Infect Immun. 2010;78:2877–2889. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00088-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foulston L, Elsholz AK, DeFrancesco AS, Losick R. The extracellular matrix of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms comprises cytoplasmic proteins that associate with the cell surface in response to decreasing pH. MBio. 2014;5:e01667-14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01667-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dengler V, Foulston L, DeFrancesco AS, Losick R. An electrostatic net model for the role of extracellular DNA in biofilm formation by Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2015;197:3779–3787. doi: 10.1128/JB.00726-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boles BR, Thoendel M, Roth AJ, Horswill AR. Identification of genes involved in polysaccharide-independent Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Webb JS, et al. Cell death in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:4585–4592. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.15.4585-4592.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Renelli M, Matias V, Lo RY, Beveridge TJ. DNA-containing membrane vesicles of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 and their genetic transformation potential. Microbiology. 2004;150:2161–2169. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26841-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salgado-Pabón W, et al. Increased expression of the type IV secretion system in piliated Neisseria gonorrhoeae variants. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:1912–1920. doi: 10.1128/JB.01357-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santiago M, et al. A new platform for ultra-high density Staphylococcus aureus transposon libraries. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:252. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1361-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mann EE, et al. Modulation of eDNA release and degradation affects Staphylococcus aureus biofilm maturation. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5822. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valentino MD, et al. Genes contributing to Staphylococcus aureus fitness in abscess- and infection-related ecologies. MBio. 2014;5:e01729-14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01729-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weng M, Nagy PL, Zalkin H. Identification of the Bacillus subtilis pur operon repressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7455–7459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corrigan RM, Abbott JC, Burhenne H, Kaever V, Gründling A. c-di-AMP is a new second messenger in Staphylococcus aureus with a role in controlling cell size and envelope stress. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002217. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seidl K, et al. Effect of a glucose impulse on the CcpA regulon in Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:95. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pagels M, et al. Redox sensing by a Rex-family repressor is involved in the regulation of anaerobic gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 2010;76:1142–1161. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07105.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu Y, et al. Staphylococcus epidermidis SrrAB regulates bacterial growth and biofilm formation differently under oxic and microaerobic conditions. J Bacteriol. 2015;197:459–476. doi: 10.1128/JB.02231-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsang LH, Cassat JE, Shaw LN, Beenken KE, Smeltzer MS. Factors contributing to the biofilm-deficient phenotype of Staphylococcus aureus sarA mutants. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beenken KE, et al. Epistatic relationships between sarA and agr in Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rupp ME, Archer GL. Hemagglutination and adherence to plastic by Staphylococcus epidermidis. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4322–4327. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.10.4322-4327.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lipke PN, Wojciechowicz D, Kurjan J. AG α 1 is the structural gene for the Saccharomyces cerevisiae α-agglutinin, a cell surface glycoprotein involved in cell-cell interactions during mating. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:3155–3165. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.8.3155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suzuki T, et al. Wall teichoic acid protects Staphylococcus aureus from inhibition by Congo red and other dyes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:2143–2151. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ender M, Berger-Bächi B, McCallum N. A novel DNA-binding protein modulating methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCallum N, Hinds J, Ender M, Berger-Bächi B, Stutzmann Meier P. Transcriptional profiling of XdrA, a new regulator of spa transcription in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:5151–5164. doi: 10.1128/JB.00491-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Truong-Bolduc QC, Dunman PM, Strahilevitz J, Projan SJ, Hooper DC. MgrA is a multiple regulator of two new efflux pumps in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:2395–2405. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.7.2395-2405.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Utaida S, et al. Genome-wide transcriptional profiling of the response of Staphylococcus aureus to cell-wall-active antibiotics reveals a cell-wall-stress stimulon. Microbiology. 2003;149:2719–2732. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26426-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dengler V, Meier PS, Heusser R, Berger-Bächi B, McCallum N. Induction kinetics of the Staphylococcus aureus cell wall stress stimulon in response to different cell wall active antibiotics. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Truong-Bolduc QC, Hooper DC. The transcriptional regulators NorG and MgrA modulate resistance to both quinolones and β-lactams in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:2996–3005. doi: 10.1128/JB.01819-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang R, et al. Identification of novel cytolytic peptides as key virulence determinants for community-associated MRSA. Nat Med. 2007;13:1510–1514. doi: 10.1038/nm1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beaume M, et al. Cartography of methicillin-resistant S. aureus transcripts: Detection, orientation and temporal expression during growth phase and stress conditions. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10725. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abu-Qatouseh LF, et al. Identification of differentially expressed small non-protein-coding RNAs in Staphylococcus aureus displaying both the normal and the small-colony variant phenotype. J Mol Med (Berl) 2010;88:565–575. doi: 10.1007/s00109-010-0597-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Howden BP, et al. Analysis of the small RNA transcriptional response in multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus after antimicrobial exposure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:3864–3874. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00263-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rice KC, et al. The cidA murein hydrolase regulator contributes to DNA release and biofilm development in Staphylococcus aureus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:8113–8118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610226104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heilmann C, Hartleib J, Hussain MS, Peters G. The multifunctional Staphylococcus aureus autolysin aaa mediates adherence to immobilized fibrinogen and fibronectin. Infect Immun. 2005;73:4793–4802. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.8.4793-4802.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bose JL, Lehman MK, Fey PD, Bayles KW. Contribution of the Staphylococcus aureus Atl AM and GL murein hydrolase activities in cell division, autolysis, and biofilm formation. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42244. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mashruwala AA, Guchte AV, Boyd JM. Impaired respiration elicits SrrAB-dependent programmed cell lysis and biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus. eLife. 2017;6:6. doi: 10.7554/eLife.23845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]