Abstract

The objectives of this study were to assess within-person hypotheses regarding temporal cognition-pain associations: 1) do morning pain flares predict changes in two afternoon adaptive and maladaptive pain-related cognitions, and 2) do these changes in afternoon cognitions predict changes in end-of-day pain reports, which in turn, carry over to predict next morning pain in individuals with fibromyalgia. Two hundred twenty individuals with fibromyalgia completed electronic assessments of pain intensity, pain catastrophizing, and pain coping efficacy three times a day for three weeks. Multilevel structural equation modeling established that afternoon catastrophizing and coping efficacy were parallel mediators linking late morning with end-of-day pain reports (controlling for afternoon pain), in line with prediction. Catastrophizing was a stronger mediator than coping efficacy. Moreover, afternoon cognitions and end-of-day pain reports served as sequential mediators of the relation between same-day and next-day morning pain. These findings align with assertions of cognitive-behavioral theories of pain that pain flares predict changes in pain both adaptive and maladaptive cognitions, which in turn, predict further changes in pain.

Keywords: chronic pain, fibromyalgia, pain cognitions, catastrophizing, pain coping efficacy, daily process methodology, multilevel structural equation modeling

Chronic pain is a prevalent problem associated with significant psychological, social, and physical disability (Becker et al., 1997; McWilliams et al., 2004). Prevailing models posit that how individuals think about their pain plays a critical role in the pain experience (Turk, 2002). Indeed, individuals who respond to pain flares with more thoughts that emphasize their capacity to effectively manage pain and fewer thoughts that focus on their negative experience of pain report less pain than their counterparts with less adaptive cognitive patterns (Gatchel et al., 2007; Quartana et al., 2009). The most commonly studied maladaptive pain cognition is catastrophizing, which is characterized by magnification of the threat associated with pain, helplessness in the face of pain, and preoccupation with pain (Quartana et al., 2009). In contrast, a commonly studied adaptive pain cognition is the perception that one is able to cope with the pain (pain coping efficacy) (Jackson et al., 2014). Most research regarding the role of cognitions in chronic pain has employed one-time assessments to examine the pain-cognition link (Arnstein, 2000; Härkäpää, 1991; Härkäpää et al., 1991; Sullivan et al., 2001). For example, among individuals with chronic pain, pain coping efficacy predicts lower pain intensity (Arnstein, 2000) and catastrophizing predicts higher pain intensity (Flor et al., 1993). Less empirical attention has been paid to exploring whether adaptive and maladaptive pain cognitions play distinct roles in the dynamics of within-day pain.

Diary methods enable the evaluation of temporally-ordered within-person experiences to test whether pain cognitions dampen or enhance the daily pain cycle. The few diary studies of individuals with chronic pain that have examined the links between pain and subsequent pain cognitions, or between pain cognitions and subsequent pain, report patterns similar to those found in cross-sectional work. For example, end-of-day reports of elevations in one day’s pain coping efficacy predict lower levels of next-day pain (Keefe et al., 1997), and morning reports of elevations in pain catastrophizing predict higher pain six hours later (Holtzman & DeLongis, 2007). The limited data available also demonstrate that pain elevations predict subsequent elevations in maladaptive pain-related cognitions, e.g., days of higher than usual pain are associated with greater next-day catastrophizing (Sturgeon & Zautra, 2013). However, no studies have tested whether pain-related cognitions mediate the pain process by examining multiple time points within a day. Focusing on within-day relations allows for elaboration of the links between pain and cognitions without the confounding effects of sleep (Stone et al., 1997).

The majority of diary studies have focused on maladaptive cognitions, especially catastrophizing (e.g., Sturgeon & Zautra, 2013). Yet there is reason to predict that adaptive and maladaptive pain cognitions represent inversely-related but separable constructs and may operate as distinct mediators in the pain process. One within-day analysis, for example, found that among individuals with chronic back pain, both morning pain control and catastrophizing significantly predicted end-of-day pain reports, controlling for morning pain (Grant et al., 2002). No within-person studies to our knowledge have determined whether adaptive and maladaptive pain cognitions represent distinct mediators in the pain process throughout a day, information that can point to one means of promoting treatment efficiency.

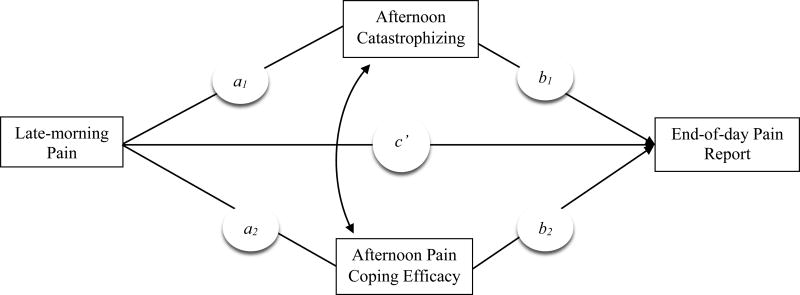

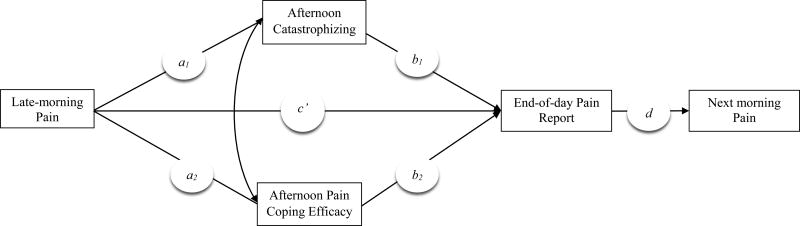

We examined whether adaptive and maladaptive pain-related cognitions assessed in the afternoon served as parallel mediators linking daily late-morning pain with end-of-day pain reports (see Figure 1), among individuals with fibromyalgia (FM), a condition characterized by widespread pain, fatigue, and nonrestorative sleep (Mease, 2005). Because they have been established as predictors of within-person changes in pain, we included pain coping efficacy as an adaptive cognition associated with decreases in pain (Keefe et al., 1997) and catastrophizing as a maladaptive cognition associated with increases in pain (Holtzman & DeLongis, 2007). On days of high morning pain, individuals were expected to report higher than their usual levels of catastrophizing and lower levels of pain coping efficacy in the afternoon, which in turn, were expected to predict higher than their usual pain at the end of the day. We also evaluated the relative strength of catastrophizing and pain coping efficacy in the daily pain process. In addition, we examined whether the impact of cognitions on end-of-day pain reports would extend to the next morning. We assessed these carry-over effects using a model that tested whether afternoon cognitions and end-of-day pain reports served as sequential mediators of the relation between late-morning pain on one day to next-morning pain (see Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Model depicting the hypothesized relations among late-morning pain, afternoon pain cognitions, and the end-of-day pain report. The path coefficients (a1, a2, b1, b2, c') estimate the strength of the predicted associations among variables. The curved arrow represents covariation between the afternoon catastrophizing and pain coping efficacy.

Figure 2.

Model depicting the hypothesized relations among late-morning pain, afternoon pain cognitions, the end-of-day pain report, and next-morning pain. The path coefficients (a1, a2, b1, b2, c', d) estimate the strength of the predicted associations among variables. The curved arrow represents covariation between the afternoon catastrophizing and pain coping efficacy.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited in the Phoenix metropolitan area from print and online advertisements, physician referrals, and FM support groups to participate in a randomized controlled trial evaluating “mind-body” treatments for FM. Data for this study were drawn from the pre-intervention assessment of participants in the trial, prior to randomization. To be eligible for participation, individuals had to: 1) be aged 18–72, 2) be English-speaking; 3) meet the American College of Rheumatology diagnostic criteria for FM (Wolfe et al., 1990); and 4) agree to be randomized into a treatment condition. Individuals were excluded from participation if they reported: 1) a physician-diagnosed autoimmune disorder, 2) physician-diagnosed neuropathic pain, 3) involvement in pain-related litigation, 4) major surgery scheduled within the study window of 4–5 months, 5) current participation in another research study or clinical trial for pain or depression, 6) current engagement in psychosocial treatment for pain or depression; or 7) comorbid medical or psychological conditions that would seriously limit their involvement in the study procedures (e.g., psychotic disorder, severe cognitive impairment). Two hundred and seventy two individuals were enrolled into the study, of whom, 52 withdrew or were unable to be scheduled for study visits prior to diary data collection. Thus, 220 participants provided diary data. Independent samples t-tests and Chi-Squared tests of independence comparing those who withdrew from those who did not revealed that individuals who withdrew were more likely to be unemployed that those who remained in the study (χ2 = 6.15, p = .01). There were no other significant differences between those who did and did not withdraw on age, gender, ethnicity, education, income, or initial pain rating (ps > .25).

Procedure

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Arizona State University. Interested individuals were first screened for eligibility by telephone, and then were consented and underwent a tender point exam conducted during a home visit by a research nurse. The description of the intervention in the consent process included no specific details regarding treatment. Rather, participants were informed that they would be randomly assigned to one of three types of groups, each of which addressed different aspects of the problems people with FM experience. The tender point exam (Okifuji et al., 1997) determined whether the participants met diagnostic criteria for FM (i.e., pain on at least 11 of 18 tender points) and were therefore eligible for the study.

As part of the pre-intervention assessment, participants completed electronic daily diaries that included assessment of their daily physical and psychological experiences. Participants were provided with a mobile phone and trained by a research assistant to use the phone to complete electronic diaries. Participants were prompted to complete the diary reports four times per day for up to 21 days via an automated phone system that called the participant: 1) each morning 30 minutes following his/her specified wake-up time for the morning interview, which assessed sleep quality only; 2) at 11:00 a.m. for the late morning interview; 3) at 4:00 p.m. for the afternoon interview; and 4) at 7:00 p.m. for the end-of-day interview. The Interactive Voice Response system (Telesage SmartQ software version 5.4.79), administered by the Informatics Core at University of Connecticut Health Center Clinical Research Center, delivered audio-recorded questions and recorded participants’ responses through use of the phone keypad. If the participant missed the call, he/she could call the system within 2.5 hours to complete the assessment. The average time interval between afternoon and end-of-day calls across 3374 observations was 3 h, 24 min (SD = 1 h, 5 min), indicating that there was a meaningful temporal lag between these assessments. Participants’ completion of diary calls was monitored by research team members, and individuals were contacted if they failed to complete assessments across two consecutive days to remedy any potential issues. Participants were encouraged to call laboratory staff immediately if a problem occurred with the phone system. Participants were compensated $2/day for each of the 21 days they completed, with a bonus of $1/day for rates of completion > 50%. Data were drawn from the late morning, afternoon, and end-of-day reports for the current study. In addition to pain and cognition variables reported in the current study, participants were also asked in their diary calls about fatigue, physical functioning, positive and negative affect, positive and negative daily events, depression symptoms, and interpersonal interactions.

Measures

Pain

Pain intensity was measured on a widely-used 101-point numerical rating scale (Jensen et al., 1986) in the late morning and end-of-day reports, permitting evaluation of within-day changes in pain. Participants rated their level of pain (i.e., “What was your overall level of pain?”) on a 101-point scale (0 =“no pain”; 100 =“pain as bad as it can be”). The 1-item scale has been shown to be equal or superior to other rating scales assessing pain in terms of validity and reliability (Jensen et al., 1986). Participants rated their overall level of pain in the past two to three hours for the late morning assessment and for the entire day at the end-of-day report. Because the end-of-day assessment references the entire day, end-of-day pain report is meant to signal an approximation of end-of-day pain.

Pain Cognitions

Participants were instructed to report the degree to which they experienced specific cognitions in the past two to three hours on a five-point scale that ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (completely). Catastrophizing was assessed with the item “You felt your pain was so bad you couldn’t stand it anymore,” from the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (Sullivan et al., 1995). Pain coping efficacy was assessed with the item “You coped effectively with your pain,” which was developed based on two items from the Coping Strategies Questionnaire (Affleck et al., 1992; Keefe et al., 1997; Rosenstiel & Keefe, 1983; Stone & Neale, 1984). The original two items tapped the extent to which individuals felt they could control their pain or decrease their pain based on their coping efforts.

Covariates

Afternoon pain and fatigue were assessed as potential covariates. Both were measured in the afternoon assessment of the diaries. Participants rated their level of fatigue (pain) for the past two to three hours (i.e., “What was your overall level of fatigue (pain)?”) on a 101-point scale (0 =“no fatigue (pain)”; 100 =“fatigue (pain) as bad as it can be”) (Jensen et al., 1986).

Missing Data

During the 21-day assessment period, participants completed an average of 17.90 days (SD = 4.42) of late-morning pain ratings; 16.93 days (SD = 4.93) of afternoon pain, catastrophizing, and pain coping efficacy ratings; and 17.23 days (SD = 4.82) of end-of-day pain ratings. Overall, participants completed 11,469 out of a total of 13,860 possible observations (83% completion rate).

To assess the model assumption that data were missing at random, we conducted independent samples t-tests to determine whether afternoon diary values of potentially influential variables (i.e., pain, fatigue) predicted a missing vs. non-missing value for the end-of-day pain report. Higher afternoon pain was related to greater rates of missingness at the end-of-day time point (t (3732) = 2.45, p = .01), whereas fatigue was not (t (3732) = 1.54, p = .12). Thus, afternoon pain was included in the model as a covariate to account for this effect.

Data Analytic Strategy

The study data had a two-level hierarchical structure: the first level was diary day (within-person), which was nested within the second level, individuals (between-person). Thus, a multilevel data analytic strategy, multilevel structural equation modeling (MSEM; Jensen et al., 1986; Preacher et al., 2010), was employed to test study hypotheses. Full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimator was used to estimate direct and mediated models. This estimation routine separates the total variance into two orthogonal components: within-person and between-person. These two components are modeled simultaneously to produce unbiased parameter estimates and standard errors. FIML via an accelerated equation modeling algorithm procedure used in Mplus version 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 1999–2012) is robust to missing data, non-normality, and unbalanced cluster sizes in data (Muthén & Asparouhov, 2008; Preacher et al., 2010). Although Mplus models both within- and between-person effects, the focus of the current paper is on the within-person relations; thus, only the within-person results are reported.

MSEM was employed to estimate the hypothesized models using Mplus version 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 1999–2012). First, a parallel mediation model was estimated in a multilevel framework to test: 1) the relations between late morning pain and both afternoon catastrophizing and pain coping efficacy (paths a1 and a2, respectively, in Figure 1); and 2) the relations between afternoon catastrophizing and pain coping efficacy and the end-of-day pain report (paths b1 and b2, respectively, in Figure 1). Afternoon pain was included as a covariate of end-of-day pain report, and was modeled to covary with the purported mediators, i.e., catastrophizing and coping efficacy. The models were tested according to the recommendations provided by Preacher and colleagues (Preacher et al., 2010). Consistent with the MSEM approach, all paths were specified to have random intercepts and fixed slopes with one exception; the relation between ratings of late morning pain and the end-of-day pain report was specified to have a random intercept and random slope. The mediating (indirect) effects of each cognition were calculated by taking the product of the coefficients of the a and b paths (Krull & MacKinnon, 2001). The distributions of the ab paths are asymmetrical and vary according to the correlations between the a and b paths; therefore, asymmetric confidence limits for the indirect effects of each mediator were computed using RMediation (Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2011), which accounts for the correlations between the a and b paths (Kenny et al., 2003).

Finally, analyses tested the extent to which same-day afternoon pain-related cognitions carried over to predict next-morning pain via the end-of-day pain report. An additional path (d; see Figure 2), from end-of-day pain report to next morning pain was added to the original model. Thus, two pathways with two sequential mediators of the relation between same-day and next-day morning pain were proposed: 1) afternoon catastrophizing and end-of-day pain report, and 2) afternoon pain coping efficacy and end-of-day pain report. The cognitive sequential mediational chains for catastrophizing and pain coping efficacy were tested in the same model. Indirect effects were estimated using Mplus by taking the product of the coefficients of the a, b, and d paths.

Results

Demographics, Intraclass Correlations, and Intercorrelations

Sample demographics are displayed in Table 1. The means, standard deviations, intraclass correlations, and intercorrelations at the within-person level of the diary variables are depicted in Table 2. Intraclass correlations for diary variables ranged from r = .42 to .54, indicating that both between-person and within-person differences accounted for substantial variance in diary measures. Intercorrelations among diary measures yielded expected patterns. Late-morning pain was positively correlated with levels of catastrophizing and inversely correlated with levels of pain coping efficacy in the afternoon. Additionally, afternoon catastrophizing was positively correlated with the end-of-day pain report and afternoon pain coping efficacy was inversely correlated with the end-of-day pain report.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics

| Entire Sample N = 220 |

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Sample Characteristics | |

| Age [M (SD)] | 51.25 (11.02) |

| Female | 88.6% |

| Income [M] | $25 – 30K |

| Employed | 51.9% |

| Caucasian | 78.4% |

| Education [M] | 1–3 years college |

| Married | 47.7% |

Table 2.

Means, intraclass correlations (ICC), and within-person intercorrelations of daily variables

| Intercorrelations | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Measures | M (SD) | ICC | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1. Morning Pain (0–100) | 48.94 (17.61) | .49 | - | .31 | −.19 | .41 | .45 |

| 2. Afternoon Catastrophizing (1–5) | 2.17 (1.12) | .51 | - | −.33 | .48 | .41 | |

| 3. Afternoon Pain Coping Efficacy (1–5) | 3.32 (1.10) | .42 | - | −.34 | −.27 | ||

| 4. Afternoon Pain (0–100) | 53.03 (23.04) | .51 | - | .54 | |||

| 4. Evening Pain (0–100) | 54.06 (18.23) | .54 | - | ||||

Note. Correlations were estimated via Maximum Likelihood in a Two-level Random Coefficient Model in Mplus version 7.

All correlations are significant at p < .01

Test of Within-day Mediation Model

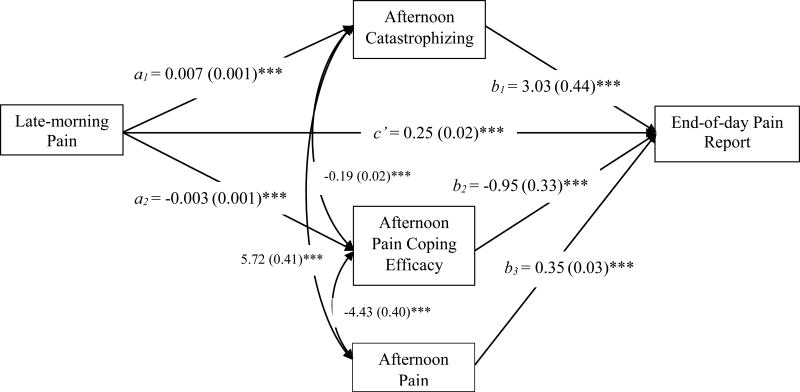

The next analysis employed a multilevel structural two-mediator model to estimate: 1) the relations between late-morning pain and both catastrophizing and pain coping efficacy (paths a1 and a2 in Figure 1); 2) the relations between catastrophizing and pain coping efficacy and the end-of-day pain report (paths b1 and b2 in Figure 1); and 3) the roles of the afternoon catastrophizing and pain coping efficacy as statistical mediators of the relation between late-morning pain and the end-of-day pain report. The results are presented in Figure 3. Consistent with prediction, at the within-person level, higher than usual late-morning pain predicted greater than usual catastrophizing (a1 path) and less than usual pain coping efficacy (a2 path) in the afternoon. Moreover, increased afternoon catastrophizing predicted a higher end-of-day pain report (b1 path), and increased afternoon pain coping efficacy predicted a lower end-of-day pain report (b2 path). Both catastrophizing and pain coping efficacy partially mediated the link between late-morning pain and the end-of-day pain report controlling for afternoon pain (a1b1 = 0.021 [SE = 0.004], 95% confidence interval [0.013, 0.031]; a2b2 = 0.003 [SE = 0.002], 95% confidence interval [0.001, 0.006]). The catastrophizing indirect pathway was stronger than the pain coping efficacy pathway: a contrast parameter created to compare the strength of the indirect paths of catastrophizing and pain coping efficacy was significant (a1b1– a2b2 = 0.017 [SE 0.004], p < .001). Of note, there was a significant direct effect of late-morning pain on the end-of-day pain report (c’ = 0.25, [SE = 0.02], p < .001), indicating that catastrophizing and pain coping efficacy only partially mediated the late-morning pain-end-of-day pain report association

Figure 3.

The parameter estimates and standard errors (in parentheses) of the direct effects of within-person mediation model of afternoon catastrophizing and pain coping efficacy as the mediators between morning and the end-of-day pain report, controlling for afternoon pain are reported in the figure. The curved arrows represent covariation between afternoon catastrophizing, pain coping efficacy, and pain. The indirect effects were as follows: a1b1 = 0.021, SE = 0.004, p < 0.001, asymmetric CI = [0.013, 0.031]; a2b2 = 0.003, SE = 0.002, p < 0.001, asymmetric CI = [0.001, 0.006]. ***p < .001.

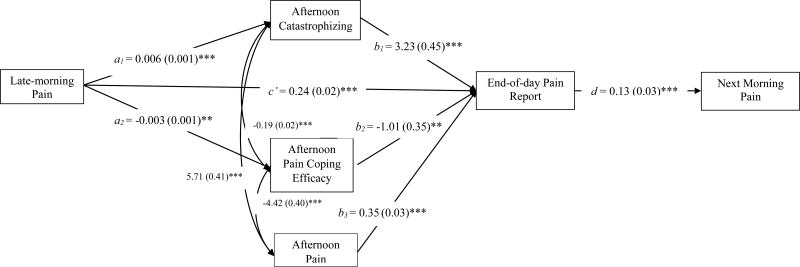

Test of Sequential Mediation Model: Same-day to Next-day Morning Pain

Next-day analyses are presented in Figure 4. As expected, today’s end-of-day pain report predicted next morning pain (d path). The mediational chain from today’s morning pain to afternoon cognitions to end-of day pain to next-morning’s pain was significant for catastrophizing (a1b1d = 0.002 [SE = 0.001] p = .001), and marginally significant for pain coping efficacy (a2b2d < 0.001 [SE < 0.001] p = .09). These lagged findings suggest that pain-related cognitions carry over to predict next morning pain.

Figure 4.

The parameter estimates and standard errors (in parentheses) of the direct effects of within-person mediation model of afternoon catastrophizing and pain coping efficacy as the mediators between morning and the end-of-day pain report, controlling for afternoon pain are reported in the figure. The curved arrows represent covariation between afternoon catastrophizing, pain coping efficacy, and pain. The indirect effects were as follows: a1b1d = 0.002, SE = 0.001, p = 0.001; a2b2d < 0.001, SE < 0.001, p = 0.09. ***p < .001, ** p < .01.

Discussion

Cognitive-behavioral theories of pain assert that: 1) pain can elicit changes in an individual’s thinking about pain in the form of more maladaptive and less adaptive appraisals of the pain and the individual’s capacity to cope with it (Cohen et al., 1995; Cohen & Wills, 1985; Thorn & Dixon, 2007; Turk, 2002), and 2) maladaptive thinking about pain can lead to subsequent increases in pain (Turk, 2002). The current study tested these assertions by examining within-day links between late-morning pain, afternoon pain-related cognitions, and end-of-day pain as well as next-morning pain, in individuals with FM. The findings were consistent with predictions. When individuals’ reacted to morning pain flares with more than usual afternoon catastrophizing and less than usual pain coping efficacy, their ratings of end-of-day pain were elevated. Of note, catastrophizing was a stronger mediator of the within-day relation between morning and end-of-day pain report than was pain coping efficacy. Moreover, pain cognitions served as mediators in the chain linking same-day with next-day morning pain.

The current findings among individuals with FM align with the well-documented cross-sectional links between pain and pain-related cognitions among individuals with chronic pain (e.g., Arnstein, 2000; Härkäpää, 1991; Härkäpää et al., 1991; Sullivan et al., 2001). They also add to the growing literature that draws on diary-based methods to focus on the interplay between pain and cognitions within each individual’s experience. Other within-person studies of individuals with chronic pain have observed that morning pain flares predict increased end-of-day maladaptive thinking (e.g., Holtzman & Delongis, 2007), and that daily reports of increases in maladaptive thoughts (e.g., catastrophizing) and decreases in adaptive thoughts (e.g., pain self-efficacy) predict greater pain both concurrently and subsequently (Grant et al., 2002; Holtzman & DeLongis, 2007; Keefe et al., 1997; Sturgeon & Zautra, 2013). Because ideas about the causal nature of links between pain and cognitions are central to the theory underlying cognitive-behavioral approaches to understanding the pain process and treating chronic pain, many may assume that this pathway of mediation been demonstrated previously. However, the current findings are the first to show a temporally-ordered mediating role for pain cognitions in the link between morning and end-of-day pain, and carryover effects to next-day pain. Although these effects were modest in magnitude, accounting for even small influences on daily pain exacerbations could be quite meaningful when accrued over a lifetime of managing chronic pain.

Additionally, these results complement limited cross-sectional (Evers et al., 2001) and within-person (Grant et al., 2002) evidence suggesting that adaptive and maladaptive cognitions play distinct roles in the pain process. Our study is the first to demonstrate these independent roles in the within-day daily pain cycle. Catastrophizing and pain coping efficacy were related at the within-person level (r = −.19), indicating that they share about 3.6% of their variance and suggesting that they are largely distinct; they are not simply two ends of the same continuum. Put differently, even when individuals tend to react with intense negative thoughts in reaction to pain, they may be able to concurrently sustain their level of positive thoughts. Future efforts should focus on replication as single item measures of catastrophizing and pain coping efficacy used here to reduce participant burden may not fully express the multidimensional nature of these constructs.

The more robust mediating role of catastrophizing relative to pain coping efficacy on the within-day pain process may have relevance for targeting clinical efforts. If daily pain intensity is the primary intervention target, our results suggest that focusing psychotherapy on restructuring and reducing maladaptive pain cognitions including catastrophizing may be the most effective strategy to interrupt the daily pain process, especially if the intervention is time-limited. Nevertheless, the weaker yet still significant role of adaptive cognitions represents a viable target for treatment and should not be overlooked. Work in individuals with pain due to chronic illness suggests that in addition to affecting pain outcomes, adaptive cognitions independently predict a number of beneficial changes in psychological health (e.g., positive mood, optimism, and active coping) compared to maladaptive cognitions, and thus could contribute to better adjustment to pain and overall quality of life (Evers et al., 2001). Future randomized controlled trials evaluating CBT for pain should examine these questions utilizing diary data to measure both within- and between-person changes in cognitive mechanisms of change (e.g., Davis et al., 2015).

This study has some important limitations that constrain interpretation of the findings. First, because the data are correlational, no conclusions can be made about causal links between pain and cognitions. Second, the study sample was comprised of treatment-seeking individuals with FM who were predominantly female, Caucasian, and middle-aged; thus, findings cannot be generalized to individuals with other chronic pain conditions, or to those who are male, not seeking treatment, or more ethnically diverse. Third, all assessments were based on self-reports. Using objective measures, such as assessment of physiological indices would permit a more comprehensive evaluation of the links between daily pain and cognitions. Fourth, the end-of-day pain report was measured at 7:00 PM, which enabled diary data collection near a common time before all participants retired for the night. However, many participants likely stayed awake after this phone call, leaving nighttime pain unmeasured. Additionally, end-of-day pain was assessed by asking participants to rate their overall level of pain for the entire day, rather than only for the evening hours. Hence, in the within-day analyses, the timeframe of the end-of-day pain report had temporal overlap with the morning pain assessment. We addressed this potential bias in two ways. First, we employed a covariate approach, both by modeling a direct path from morning to end-of-day pain, and by controlling for the path between afternoon pain and end-of-day pain. Thus, we statistically adjusted for the variance in end-of-day pain reports that were accounted for by morning and afternoon pain in within-day analyses. Second, we demonstrated the carry-over effect of pain-related catastrophizing to next-morning pain, assessments with no temporal overlap. Nonetheless, an ideal approach would include assessment of an identical time frame across all assessments. Finally, catastrophizing and pain coping efficacy did not fully account for the link between late morning and the end-of-day pain report. Many additional adaptive and maladaptive pain cognitions are likely involved in the daily pain process. Diary studies have identified other pain cognitions with links to pain, e.g., pain control (Grant et al., 2002). A number of additional possible mediators of the within-day pain cycle can be drawn from evidence from other within-day analyses of chronic pain. For example, on a daily basis, pain predicts changes in affect (Zautra et al., 2001), physical activity level (Taylor et al., 2013), social functioning (Sturgeon & Zautra, 2015), and behaviors (e.g., relaxation (Keefe et al., 1997), pursuit of meaningful goals (Affleck et al., 1998), and praying and hoping (Grant et al., 2002)), which in turn, may influence subsequent pain. Elaborating the multiple mechanisms that exacerbate or diminish daily pain is essential to the development of the most efficient and effective interventions for FM and other chronic pain conditions.

Limitations notwithstanding, this study also had some notable strengths. First, the multiple within-day reports of pain and cognitions over a three-week time period reduced recall error and bias and produced reliable estimates of the within-day covariation between these variables. Second, capturing three consecutive time points within-day and examining carry-over effects to next-day offered the opportunity to examine temporal precedence to elucidate the theorized reciprocal relation between pain and cognitions throughout the course of a day and over days. Third, covarying afternoon pain and its link with end-of-day pain highlights a mediating role for afternoon cognitions in the daily pain process distinct from current pain experience. Fourth, examining both adaptive and maladaptive cognitions in the same model offered a better approximation of real-time multidimensional cognitive responses to a pain flare. Finally, participants also showed good adherence to completing the diary calls, resulting in relatively few missing data.

In conclusion, both adaptive and maladaptive pain cognitions (i.e., catastrophizing and pain coping efficacy) mediate the relation between late morning pain flares and end-of-day pain, and next-morning pain among individuals with FM pain. These findings are in line with cognitive-behavioral treatment models, which target change in pain cognitions as a means of bolstering functional health among pain patients.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: Funded by NIAMS grant 5R01AR053245, PI: Dr. Davis. Dr. Taylor was supported by a VA OAA Fellowship TPP 21-027. Dr. Yeung was supported by a NIAAA Fellowship T32AA013526.

The contents do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Abbreviations

- FM

fibromyalgia

- MSEM

multilevel structural equation modeling

- FIML

full information maximum likelihood

- CBT

cognitive-behavioral therapy

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Affleck G, Tennen H, Urrows S, Higgins P, Abeles M, Hall C, Newton C. Fibromyalgia and women's pursuit of personal goals: a daily process analysis. Health Psychology. 1998;17(1):40. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Affleck G, Urrows S, Tennen H, Higgins P. Daily coping with pain from rheumatoid arthritis: patterns and correlates. Pain. 1992;51(2):221–229. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90263-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnstein P. The mediation of disability by self efficacy in different samples of chronic pain patients. Disability and Rehabilitation: An International, Multidisciplinary Journal. 2000;22(17):794–801. doi: 10.1080/09638280050200296. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09638280050200296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker N, Thomsen AB, Olsen AK, Sjøgren P, Bech P, Eriksen J. Pain epidemiology and health related quality of life in chronic non-malignant pain patients referred to a Danish multidisciplinary pain center. Pain. 1997;73(3):393–400. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00126-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kessler RC, Gordon LU. Strategies for measuring stress in studies of psychiatric and physical disorders. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological bulletin. 1985;98(2):310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MC, Zautra AJ, Wolf LD, Tennen H, Yeung EW. Mindfulness and cognitive–behavioral interventions for chronic pain: Differential effects on daily pain reactivity and stress reactivity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015;83(1):24–35. doi: 10.1037/a0038200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehde DM, Dillworth TM, Turner JA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for individuals with chronic pain: efficacy, innovations, and directions for research. American Psychologist. 2014;69(2):153. doi: 10.1037/a0035747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers AW, Kraaimaat FW, van Lankveld W, Jongen PJ, Jacobs JW, Bijlsma JW. Beyond unfavorable thinking: the illness cognition questionnaire for chronic diseases. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69(6):1026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flor H, Behle DJ, Birbaumer N. Assessment of pain-related cognitions in chronic pain patients. Behaviour research and therapy. 1993;31(1):63–73. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(93)90044-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatchel RJ, Peng YB, Peters ML, Fuchs PN, Turk DC. The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: scientific advances and future directions. Psychological bulletin. 2007;133(4):581. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George SZ, Zeppieri G, Cere AL, Cere MR, Borut MS, Hodges MJ, Robinson ME. A randomized trial of behavioral physical therapy interventions for acute and sub-acute low back pain ( NCT00373867) Pain. 2008;140(1):145–157. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant LD, Long BC, Willms JD. Women’s adaptation to chronic back pain: Daily appraisals and coping strategies, personal characteristics and perceived spousal responses. Journal of Health Psychology. 2002;7(5):545–563. doi: 10.1177/1359105302007005675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Härkäpää K. Relationships of psychological distress and health locus of control beliefs with the use of cognitive and behavioral coping strategies in low back pain patients. The Clinical journal of pain. 1991;7(4):275–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Härkäpää K, Järvikoski A, Mellin G, Hurri H, Luoma J. Health locus of control beliefs and psychological distress as predictors for treatment outcome in low-back pain patients: Results of a 3-month follow-up of a controlled intervention study. Pain. 1991;46(1):35–41. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90031-R. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0304-3959(91)90031-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzman S, DeLongis A. One day at a time: The impact of daily satisfaction with spouse responses on pain, negative affect and catastrophizing among individuals with rheumatoid arthritis. Pain. 2007;131(1):202–213. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson T, Wang Y, Wang Y, Fan H. Self-efficacy and chronic pain outcomes: A meta-analytic review. The Journal of Pain. 2014;15(8):800–814. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MP, Karoly P, Braver S. The measurement of clinical pain intensity: a comparison of six methods. Pain. 1986;27(1):117–126. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(86)90228-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe FJ, Affleck G, Lefebvre JC, Starr K, Caldwell DS, Tennen H. Pain coping strategies and coping efficacy in rheumatoid arthritis: a daily process analysis. Pain. 1997;69(1):35–42. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(96)03246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Korchmaros JD, Bolger N. Lower level mediation in multilevel models. Psychological methods. 2003;8(2):115. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.8.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krull JL, MacKinnon DP. Multilevel modeling of individual and group level mediated effects. Multivariate behavioral research. 2001;36(2):249–277. doi: 10.1207/S15327906MBR3602_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams LA, Goodwin RD, Cox BJ. Depression and anxiety associated with three pain conditions: results from a nationally representative sample. Pain. 2004;111(1):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mease P. Fibromyalgia syndrome: review of clinical presentation, pathogenesis, outcome measures, and treatment. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2005;75:6–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Asparouhov T. Growth mixture modeling: Analysis with non-Gaussian random effects. Longitudinal data analysis. 2008:143–165. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1999–2012. [Google Scholar]

- Okifuji A, Turk D, Sinclair J, Starz T, Marcus D. A standardized manual tender point survey. I. Development and determination of a threshold point for the identification of positive tender points in fibromyalgia syndrome. The Journal of rheumatology. 1997;24(2):377–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Zyphur MJ, Zhang Z. A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological methods. 2010;15(3):209. doi: 10.1037/a0020141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quartana PJ, Campbell CM, Edwards RR. Pain catastrophizing: a critical review. Expert review of neurotherapeutics. 2009;9(5):745–758. doi: 10.1586/ERN.09.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstiel AK, Keefe FJ. The use of coping strategies in chronic low back pain patients: relationship to patient characteristics and current adjustment. Pain. 1983;17(1):33–44. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(83)90125-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone AA, Broderick JE, Porter LS, Kaell AT. The experience of rheumatoid arthritis pain and fatigue: examining momentary reports and correlates over one week. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1997;10(3):185–193. doi: 10.1002/art.1790100306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone AA, Neale JM. New measure of daily coping: Development and preliminary results. Journal of personality and social psychology. 1984;46(4):892. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.46.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturgeon JA, Zautra AJ. State and trait pain catastrophizing and emotional health in rheumatoid arthritis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2013;45(1):69–77. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9408-z. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12160-012-9408-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturgeon JA, Zautra AJ. Social pain and physical pain: shared paths to resilience. Pain Manag. 2015 doi: 10.2217/pmt.15.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan MJ, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychological assessment. 1995;7(4):524. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan MJ, Thorn B, Haythornthwaite JA, Keefe F, Martin M, Bradley LA, Lefebvre JC. Theoretical perspectives on the relation between catastrophizing and pain. The Clinical journal of pain. 2001;17(1):52–64. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200103000-00008. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00002508-200103000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SS, Davis MC, Zautra AJ. Relationship status and quality moderate daily pain-related changes in physical disability, affect, and cognitions in women with chronic pain. Pain. 2013;154(1):147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.10.004. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorn BE, Dixon KE. Coping with chronic illness and disability: Theoretical, empirical, and clinical aspects. Springer Science + Business Media; New York, NY: 2007. Coping with chronic pain: A stress-appraisal coping model; pp. 313–335. [Google Scholar]

- Tofighi D, MacKinnon DP. RMediation: An R package for mediation analysis confidence intervals. Behavior Research Methods. 2011;43(3):692–700. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0076-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turk DC. A cognitive-behavioral perspective on treatment of chronic pain patients. In: Turk DC, Gatchel RJ, editors. Psychological approaches to pain management: A practitioners handbook. 2. New York, Ny: Guilford; 2002. pp. 138–158. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, Bennett RM, Bombardier C, Goldenberg DL, Clark P. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1990;33(2):160–172. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zautra A, Smith B, Affleck G, Tennen H. Examinations of chronic pain and affect relationships: applications of a dynamic model of affect. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69(5):786. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.5.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]