Abstract

Background

Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) catalyzes the rate-limiting step of tryptophan (Trp) degradation via the kynurenine (Kyn) pathway, which inhibits the proliferation of T cells and induces the apoptosis of T cells, leading to immune tolerance. Therefore, IDO has been considered as the most important mechanism for tumor cells to escape from immune response. Previous studies suggested that IDO might be involved in the progression of tumor and resistance to chemotherapy. Several preclinical and clinical studies have proven that IDO inhibitors can regulate IDO-mediated tumor immune escape and potentiate the effect of chemotherapy. Thus, the present study investigated the correlation between the clinical parameters, responses to chemotherapy, and IDO activity to provide a theoretical basis for the clinical application of IDO inhibitors to improve the suppression status and poor prognosis in cancer patients.

Methods

The serum concentrations of Trp and Kyn were measured by high-performance liquid chromatography in 252 patients with stage IIIB or IV non-small-cell lung cancer, and 55 healthy controls. The IDO activity was determined by calculating the serum Kyn-to-Trp (Kyn/Trp) ratio.

Results

The IDO activity was significantly higher in the lung cancer patients than in the controls (median 0.0389 interquartile range [0.0178–0.0741] vs 0.0111 [0.0091–0.0133], respectively; P<0.0001). In addition, patients with adenocarcinoma had higher IDO activity than patients with nonadenocarcinoma (0.0449 [0.0189–0.0779] vs 0.0245 [0.0155–0.0563], respectively; P=0.006). Furthermore, patients with stage IIIB disease had higher IDO activity than patients with stage IV disease (0.0225 [0.0158–0.0595] vs 0.0445 [0.0190–0.0757], respectively; P=0.012). The most meaningful discovery was that there was a significant difference between the partial response (PR) patients and the stable disease (SD) and progressive disease (PD) patients (0.0240 [0.0155–0.0381] vs 0.0652 [0.0390–0.0831] vs 0.0868 [0.0209–0.0993], respectively, P<0.0001).

Conclusion

IDO activity was increased in lung cancer patients. Higher IDO activity correlated with histological types and disease stages of lung cancer patients, induced the cancer cells’ resistance to chemotherapy, and decreased the efficacy of chemotherapy.

Keywords: advanced non-small-cell lung cancer; indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; immune escape; chemotherapy response; tumor immunotherapy

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide.1 Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) comprises ~85% of all lung cancer patients.2 Among patients with NSCLC, ~70% present with locally advanced nonresectable disease (stage IIIB)3 or metastatic disease (stage IV),4 which means that these patients will have a median survival time of 4–5 months since diagnosis and only 10% of them will survive for 1 year.5,6 For patients with advanced-stage NSCLC, chemotherapy with a platinum doublet offers the median overall survival (OS) of 10 months.7 Recent introduction of molecularly targeted therapies for NSCLC resulted in clinically meaningful OS improvements. However, only selected patients whose tumors exhibit specific oncogene addiction can benefit from the targeted therapies.8 Unfortunately, almost all patients eventually acquire resistance to targeted therapies.9–11 Therefore, lung cancer remains a disease with dismal prognosis, and novel therapies focused on new target are urgently needed.

In tumor immunology, the basic function of the host immune system is to differentiate between normal cells and cancer cells to protect the body from the damage caused by the cancer cells.12 T cells play a key role in cell-mediated immunity. During the immune response, however, some of the transformed cancer cells employ several immune evasion strategies to generate an immunosuppressive microenvironment to overcome the immune response, resulting in tumor progression.13–17 The most important mechanism of immune tolerance by which cancer cells escape the immune system is to diminish local tryptophan (Trp) by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO).18,19

IDO is a key enzyme that catalyzes the initial and rate-limiting steps in the Trp degradation along the kynurenine (Kyn) pathway to form Kyn, which is converted into several metabolites through downstream enzymes.20 For many years, IDO has been known as an innate defense mechanism, limiting the growth of viruses, bacteria, and intracellular pathogens by consuming Trp in the local microenvironment.21,22 IDO activity can be quantified by measuring the serum Kyn-to-Trp (Kyn/Trp) ratio using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) because Kyn is the first product formed through catabolizing Trp, which is tightly regulated by IDO. Therefore, a high Kyn/Trp ratio reflects an enhanced IDO activity.23–26

Increased expression of IDO has been observed in wide range of types of human solid tumors, such as colorectal, breast, ovarian, and lung cancers and melanoma,27–31 as well as in hematological malignancies, including acute myeloid leukemia32 and lymphoma.33 Within the tumor microenvironment, constitutive expression of IDO, which is expressed by cancer cells as well as by some tumor infiltrating cells, for example, dendritic cells (DCs),18,27,34,35 can be detected in the peritumoral stroma and in tumor-draining lymph nodes.34,36 IDO induces peripheral immunotolerance and immunosuppression by the following mechanisms: 1) reducing the local concentration of Trp and starving T cells from the important amino acid, resulting in the inhibition of T-cell proliferation,37–39 2) producing immunomodulatory toxic metabolites, such as Kyn (kynurenic acid [Kyna]), which efficiently suppress the function of T cells, render T cells more sensitive to apoptosis, and promote the differentiation of naive T cells into regulatory T cells (Tregs) that can directly inhibit the host immune response,18,20,27,40–42 and 3) secreting immunosuppressive cytokines, such as IL-10 and TGF-β, to protect tumor form host immunity.43,44 To date, a large number of studies have shown that high expression of IDO is predictive of shorten survival in a variety of human malignancies, including solid tumors (lung,34,45,46 colorectal,47–49 endometrial,50,51 ovarian,52–55 hepatocellular,56 and breast57–60 cancers, malignant melanoma,61,62 gynecological,63 cervical,64,65 esophageal,66–68 and pancreatic ductal69 cancers, osteosarcoma,70 and brain cancer71) and various hematological tumors, such as myeloma,72 leukemia,73–77 and lymphoma.33,78–80

In several preclinical studies, the IDO-blocking agent 1-methyl-Trp (1-MT) has shown remarkable ability to inhibit IDO activity and cooperate with cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents in inhibiting the growth of cancer cells in animal models.81,82

Although the above studies suggest critical relationship between IDO and disease progression in cancer, there have been no studies focusing on the relationship among the activity of IDO, clinical parameters, and response to chemotherapy in patients with stage IIIB or IV NSCLC. The present study measured the serum concentrations of Trp and Kyn by HPLC and estimated the IDO activity in advanced NSCLC patients. The object of our study is to clarify the correlation between the status of suppression in lung cancer patients and the clinical characteristics as well as the response to chemotherapy of the selected patients so that we can improve the poor prognosis of these patients.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

A total of 252 patients, of whom 155 were men and 97 were women, were enrolled at our institutions from May 2015 to September 2016. The main inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) cytologically or histologically confirmed primary NSCLC; 2) stage IIIB or IV according to the seventh TNM stage classification system; 3) no anticancer treatment before the enrollment of the study, including surgery, chemotherapy, target agents, and immunotherapy; 4) patients with a computed tomography (CT) or positron-emission tomography (PET) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of evaluable primary lesions before the first cycle and third cycle of chemotherapy; and 5) Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) scale of 60 and 100 and requirement of adequate organ, bone marrow, liver, and renal functions. The main exclusion criteria are as follows: 1) autoimmune disease, viral hepatitis, or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS); 2) pregnant women; and 3) the other types of carcinoma. Histological types were classified according to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria. The study subjects also included 55 healthy blood donors serving as a control group (32 men and 23 women). Healthy subjects with recent infection, immune system disease, and malignant tumors were excluded. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shandong Cancer Hospital, who deemed written informed consent unnecessary as the experiments did not violate relevant rules of experimental ethics.

Treatment schedule

The chemotherapy regimens were used according to the histological types. Treatment schedules consisted of at least two cycles of pemetrexed (500 mg/m2) combined with cisplatin (75 mg/m2) or carboplatin (AUC =5–6) or nedaplatin (80 mg/m2) or lobaplatin (50 mg/m2); docetaxel (75 mg/m2) combined with cisplatin or carboplatin or nedaplatin; gemcitabine (1,250 mg/m2) combined with cisplatin or carboplatin or nedaplatin or lobaplatin; and etoposide (100 mg/m2) combined with cisplatin. Among them, some patients with lung adenocarcinoma were administered with bevacizumab (15 mg/kg) combined with chemotherapy agents.

Evaluation of response concerning the primary site

All the patients are required to have imaging examinations for the primary sites before the first cycle and third cycle of chemotherapy. Tumor responses were assessed as follows: complete response (CR) for the primary lesion was defined as the complete disappearance of all measurable and assessable target lesions for >4 weeks; partial response (PR) was defined as at least 30% decrease in the sum of diameters of target lesions; progressive disease (PD) was defined as a ≥20% enlargement of the tumor or the appearance of a new tumor lesion; and stable disease (SD) was defined as neither sufficient shrinkage to qualify for PR nor sufficient increase to qualify for PD.

Measurements of serum Trp and Kyn

For the patients with advanced NSCLC, venous blood samples were collected from peripheral vein after at least 12 hours of fasting before the first cycle of chemotherapy. For the healthy subjects, blood samples were collected from peripheral vein after at least 12 hours of fasting. Blood samples were centrifuged, and the separated serum samples were deep frozen and stored at -80°C immediately until further analysis. After thawing at room temperature, 200 µL of samples were acidified with 200 µL perchloric acid. Then, the samples were centrifuged for 10 minutes (10,000 rpm, 4°C), and the supernatants were centrifuged under the same conditions again for the purpose of removing precipitated proteins completely. Analyses were separated by an isocratic elution of the injected samples. Eluted Trp and Kyn was subjected to HPLC (Shimadzu LC-20A HPLC system: C18 reverse-phase column) and quantified fluorometrically (Shimadzu RF-20A fluorescence detector). Concentrations of Trp and Kyn were determined by HPLC as previously described.54 To estimate the IDO activity, the Kyn/Trp ratio was calculated.83

Statistical analysis

All continuous variables were assessed for normality of the distribution using the P–P plot. For the data that fitted normal distribution, it was presented as the mean value and standard deviation and analyzed by independent-samples t-test or one-way ANOVA. In case of skewed distributions, the median and interquartile ranges (IQRs, 25th–75th percentile) were presented and statistical analysis was performed using the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test or Mann–Whitney U test. Spearman rank correlation analysis was applied to assess correlations. P<0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Analyses were performed using the software package, version 23.0 for Windows (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Clinical characteristics

A group of 252 cytologically or histologically proven NSCLC patients with a mean age of 57.9±10.4 years and 55 healthy subjects with a mean age of 60.1±10.5 years was evaluated. The clinical characteristics of the subjects are listed in Table 1. No age and gender differences were observed between healthy controls and lung cancer patients (P>0.05). Among the patients, 54 patients were diagnosed at stage IIIB and 198 patients were diagnosed at stage IV. A total of 185 patients had lung adenocarcinoma, and the others had nonadenocarcinoma (52 squamous cell carcinoma, 8 large cell carcinoma, 4 atypical carcinoid, and 3 adenosquamous cell carcinoma). As for the response to chemotherapy, no one reached CR, 122 patients reached PR and 109 patients had SD, whereas 21 patients progressed after two cycles of chemotherapy.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer and healthy controls

| Characteristics | Patients | %a | Controls | % | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 252 | 55 | |||

| Sex | 0.647 (ns) | ||||

| Male | 155 | 61.5 | 32 | 58.2 | |

| Female | 97 | 38.5 | 23 | 41.8 | |

| Age (years) | 57.9±10.4b | 60.1±10.5b | 0.072 (ns) | ||

| Smoking status | |||||

| Former/current smoker | 128 | 50.8 | |||

| Never smoker | 124 | 49.2 | |||

| KPS scale | |||||

| ≥80 | 240 | 95.2 | |||

| <80 | 12 | 4.8 | |||

| Stage | |||||

| Stage IIIB | 54 | 21.4 | |||

| Stage IV | 198 | 78.6 | |||

| Histological type | |||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 185 | 73.4 | |||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 52 | 20.6 | |||

| Large cell carcinoma | 8 | 3.2 | |||

| Atypical carcinoid | 4 | 1.6 | |||

| Adenosquamous cell carcinoma | 3 | 1.2 | |||

| Response to chemotherapy | |||||

| PR | 122 | 48.4 | |||

| SD | 109 | 43.3 | |||

| PD | 21 | 8.3 |

Notes:

The proportion of the numbers in the total patients.

Mean ± standard deviation.

Abbreviations: KPS, Karnofsky Performance Status; ns, not significant; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

Serum Trp and Kyn and IDO activity in patients and controls

The serum concentrations of Trp and Kyn and the IDO activity are presented in Table 2. Trp concentrations in patients were significantly lower compared to those in healthy individuals (P<0.0001). Lung cancer patients had significantly higher Kyn concentrations (P<0.0001) and IDO activity (P<0.0001) than healthy controls.

Table 2.

Serum concentrations of Trp and Kyn and IDO activity in patients and controls

| Variables | Patients | Controls | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trp (µmol/L) | 27.637 (16.966–42.217)a | 33.142 (28.614–47.527) | <0.0001 |

| Kyn (µmol/L) | 1.018 (0.760–1.356) | 0.411 (0.355–0.468) | <0.0001 |

| IDO activity | 0.0389 (0.0178–0.0741) | 0.0111 (0.0091–0.0133) | <0.0001 |

Notes:

Median and IQR (25th–75th).

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; Kyn, kynurenine; IDO, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; Trp, tryptophan.

Correlation of serum Trp and Kyn and IDO activity with clinical characteristics

Patients with lung adenocarcinoma had significantly lower concentration of Trp (P=0.017) and higher IDO activity (P=0.006) with slightly higher concentration of Kyn but not significantly different (P=0.268) than the patients with nonadenocarcinoma (Table 3). However, we did not explore the difference between the patients with nonadenocarcinoma due to the limited sample size. Interestingly, comparing patients with stage IIIB disease, significant decreases in serum concentrations of Trp (P=0.018) and increases in IDO activity (P=0.012) were found in patients with stage IV disease, whereas the Kyn concentration did not reach statistical significance (Table 4).

Table 3.

Serum concentrations of Trp and Kyn and IDO activity in the different groups of histological types

| Variables | Adenocarcinoma | Nonadenocarcinoma | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trp (µmol/L) | 25.072 (15.792–39.224)a | 32.059 (20.385–45.862) | 0.017 |

| Kyn (µmol/L) | 1.033 (0.762–1.400) | 0.929 (0.738–1.282) | 0.268 |

| IDO activity | 0.0449 (0.0189–0.0779) | 0.0245 (0.0155–0.0563) | 0.006 |

Notes:

Median and IQR (25th–75th).

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; Kyn, kynurenine; IDO, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; Trp, tryptophan.

Table 4.

Serum concentrations of Trp and Kyn and IDO activity in the different groups of disease stages

| Variables | Stage IIIB | Stage IV | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trp (µmol/L) | 33.051 (21.123–47.946)a | 26.320 (16.097–39.211) | 0.018 |

| Kyn (µmol/L) | 0.924 (0.747–1.258) | 1.041 (0.762–1.403) | 0.223 |

| IDO activity | 0.0225 (0.0158–0.0595) | 0.0445 (0.0190–0.0757) | 0.012 |

Notes:

Median and IQR (25th–75th).

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; Kyn, kynurenine; IDO, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; Trp, tryptophan.

We also explored the differences between the smoking status and KPS scale with the concentrations of Trp and Kyn and IDO activity; no significant differences were observed. In addition, no correlation between patient’s age and concentrations of Trp or Kyn as well as the IDO activity was observed.

Correlation of serum Trp and Kyn and IDO activity with responses to chemotherapy

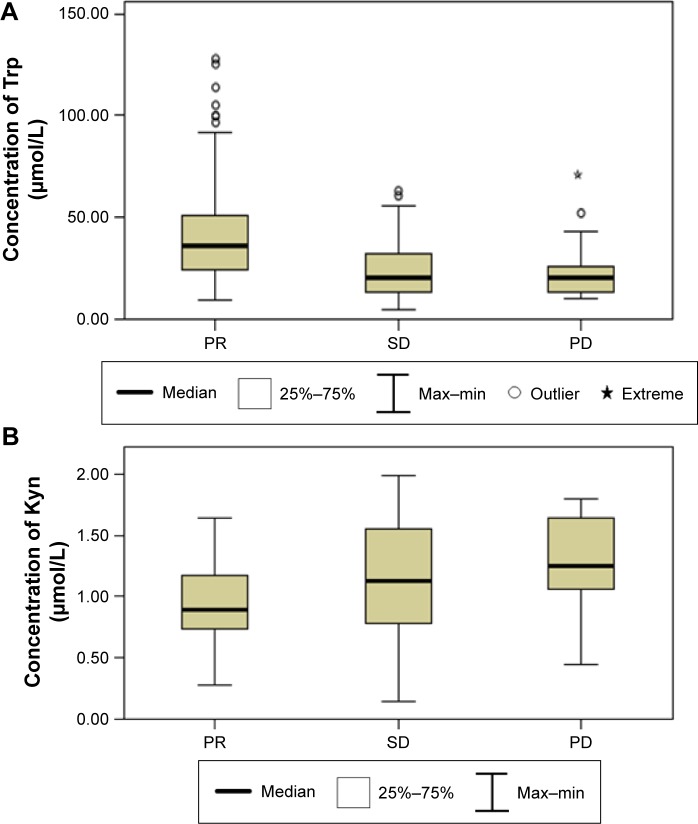

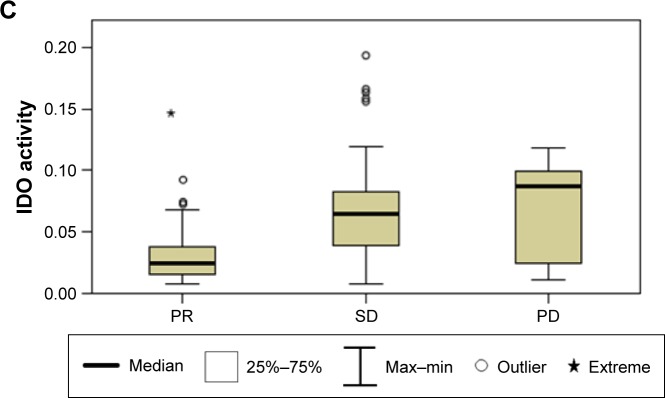

The PR patients had significantly lower concentrations of Trp with significantly higher concentrations of Kyn, resulting in higher IDO activity compared to the SD patients (P<0.0001) and PD patients (P<0.0001). However, there are no differences between the SD patients and the PD patients concerning the concentrations of Trp and Kyn and IDO activity (Table 5 and Figure 1).

Table 5.

Serum concentrations of Trp and Kyn and IDO activity in the different groups of responses to chemotherapy

| Variables | PR | SD | PD | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trp (µmol/L) | 35.536 (923.858–51.308)a | 19.941 (13.082–32.171) | 20.287 (12.987–28.646) | <0.0001 |

| Kyn (µmol/L) | 0.889 (0.730–1.176) | 1.124 (0.783–1.554) | 1.252 (0.914–1.654) | <0.0001 |

| IDO activity | 0.0240 (0.0155–0.0381) | 0.0652 (0.0390–0.0831) | 0.0868 (0.0209–0.0993) | <0.0001 |

Notes:

Median and IQR (25th–75th).

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; Kyn, kynurenine; IDO, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; Trp, tryptophan.

Figure 1.

Comparison of serum concentrations of Trp (A) and Kyn (B) and IDO activity (C) between PR patients, SD patients, and PD patients.

Notes: (A) Serum Trp level in PR patients vs SD patients (P<0.0001) and PR patients vs PD patients (P<0.0001). (B) Serum Kyn level in PR patients vs SD patients (P<0.0001) and PR patients vs PD patients (P<0.0001). (C) Serum IDO activity in PR patients vs SD patients (P<0.0001) and PR patients vs PD patients (P<0.0001).

Abbreviations: Kyn, kynurenine; IDO, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; Max, maximum; Min, minimum; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; Trp, tryptophan.

Discussion

Our study, for the first time, measured the pretreatment serum concentrations of Trp and Kyn by HPLC and estimated the activity of IDO through calculating Kyn/Trp ratio in patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC. This study showed an accelerated Trp catabolism in NSCLC patients than in healthy controls, which was consistent with previous observations in lung cancer,45,84,85 gynecologic cancer,86 breast cancer,87 malignant melanoma,61 colorectal cancer,49 thyroid cancer,88 leukemia,75,76 esophageal cancer,66,89 and ovarian cancer.90 There are several explanations for this result. The most important reason is that the IDO expressed constitutively by cancer cells and some other cells starve T cells from the important amino acid, Trp, causing them to be incapable of performing an appropriate immune response.18 The other potential reason for this phenomenon is that patients with cancer reduce dietary intake of this essential amino acid, whereas the cancer cells still consume Trp in the tumor microenvironment to protect them from the immunosurveillance.

Sagan et al91 found that Kyna level in the serum of patients with adenocarcinoma was significantly higher than that in the serum of patients with squamous cell cancer (P<0.05). Kyna is the end-stage product of the transamination side branch in the Kyn pathway.18,92,93 Therefore, the level of Kyna can reflect the activity of Kyn pathway; in other words, it can reflect the activity of IDO. Previous studies have shown that lung adenocarcinoma is characterized by more aggressive development, resulting in poorer prognosis compared to other histological types of NSCLC.94–96 This characteristic of invasiveness of lung adenocarcinoma may be attributed to the properties of the tumor itself, as well as to impaired antitumor immune response.97,98 Supporting the above theory, our data showed that the degradation of Trp and high level of IDO activity were observed in patients with adenocarcinoma than in patients with nonadenocarcinoma.

We also found that patients with metastatic lung cancer had significantly higher IDO activity than those with locally advanced lung cancer. Similarly, Suzuki et al45 reported that an increased IDO activity was discovered in advanced stages of lung cancer than in early stages of lung cancer. However, Karanikas et al46 found no significant correlation between disease stages and mRNA IDO expression by tumor tissues in 28 patients with NSCLC. This conflict may be partially attributed to the different sample sizes and methods to assess IDO expression or activity between these studies. Our results were also consistent with previous studies, which found that high expression of IDO has been associated with high frequencies of metastasis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma,56 endometrial tumors,51 and colorectal cancer.47 These results indicate that IDO activity is enhanced in patients with a larger tumor burden.

Our study discovered that there was a significant difference between the PR patients and the SD and PD patients, whereas no significant difference was found between the SD patients and the PD patients. Previous studies81 suggested that IDO might be associated with resistance to chemotherapeutic agents, which was consistent with another report showing that IDO was involved in paclitaxel resistance in ovarian cancer.52

Consequently, IDO may serve as an important target for anticancer agents. To our knowledge, several small-molecule IDO inhibitors, such as 1-MT, show effective antitumor activity in animal models, especially when they are combined with cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents, such as platinum compounds, taxane derivatives, and cyclophosphamide. The IDO inhibitors reactivate the T cells by suppressing the consumption of Trp and the production of Kyn to block the immune escape without increased toxicity.81,82,99,100 Furthermore, 1-MT has been evaluated in clinical trials to disrupt tumor tolerance in cancer patients to improve the immunosuppression status and postpone the growth of the tumor.101

Study limitations

However, there are several limitations of the present study, which should be discussed. First, the small sample size might impair the effectiveness of our results and a more robust sample size may have improved the power to detect significant differences between the levels of Trp and Kyn and IDO activity and the clinical parameters as well as the response to chemotherapy. Second, we did not examine the concentrations of the Trp and Kyn and IDO activity after standard treatment. Therefore, we cannot figure out whether IDO activity changed by chemotherapy. In addition, this study did not perform survival analysis. As a result, we cannot give the conclusion whether levels of Trp and Kyn and IDO activity can serve as prognostic factors for stage IIIB or IV NSCLC patients.

Conclusion

The present study presented that patients with stage IIIB or IV NSCLC had lower serum concentration of Trp and higher serum concentration of Kyn, resulting in more enhanced IDO activity than healthy controls, and that increased IDO activity related to the histological types and disease stages. The most important discovery of our study was that IDO activity differed significantly between the PR patients and the SD and PD patients. The result suggested that patients with an increased immunosuppression status induced by higher IDO activity might decrease the efficacy of chemotherapy. Taken together with previous studies, the combined treatment of IDO inhibitor and chemotherapy is effective in improving the immunosup-pression status and has potential clinical prospect.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Govindan R, Page N, Morgensztern D, et al. Changing epidemiology of small-cell lung cancer in the United States over the last 30 years: analysis of the surveillance, epidemiologic, and end results database. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(28):4539–4544. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.4859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auperin A, Le Pechoux C, Rolland E, et al. Meta-analysis of concomitant versus sequential radiochemotherapy in locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(13):2181–2190. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Besse B, Adjei A, Baas P, et al. 2nd ESMO Consensus Conference on Lung Cancer: non-small-cell lung cancer first-line/second and further lines of treatment in advanced disease. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(8):1475–1484. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Page DB, Bourla AB, Daniyan A, et al. Tumor immunology and cancer immunotherapy: summary of the 2014 SITC primer. J Immunother Cancer. 2015;3:25. doi: 10.1186/2051-1426-2-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schreiber RD, Old LJ, Smyth MJ. Cancer immunoediting: integrating immunity’s roles in cancer suppression and promotion. Science. 2011;331(6024):1565–1570. doi: 10.1126/science.1203486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scagliotti GV, Parikh P, von Pawel J, et al. Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(21):3543–3551. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackman DM, Miller VA, Cioffredi LA, et al. Impact of epidermal growth factor receptor and KRAS mutations on clinical outcomes in previously untreated non-small celllung cancer patients: results of an online tumor registry of clinical trials. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(16):5267–5273. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sica A, Saccani A, Bottazzi B, et al. Autocrine production of IL-10 mediates defective IL-12 production and NF-kappa B activation in tumor-associated macrophages. J Immunol. 2000;164(2):762–767. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobayashi S, Boggon TJ, Dayaram T, et al. EGFR mutation and resistance of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(8):786–792. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Awad MM, Katayama R, McTigue M, et al. Acquired resistance to crizotinib from a mutation in CD74eROS1. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(25):2395e2401. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies M. New modalities of cancer treatment for NSCLC: focus on immunotherapy. Cancer Manag Res. 2014;6:63–75. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S57550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zou W. Immunosuppressive networks in the tumor environment and their therapeutic relevance. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(4):263–274. doi: 10.1038/nrc1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zou W. Regulatory T cells, tumor immunity and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6(4):295–307. doi: 10.1038/nri1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rabinovich GA, Gabrilovich D, Sotomayor EM. Immunosuppressive strategies that are mediated by tumor cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:267–296. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunn GP, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. The three Es of cancer immunoediting. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:329–360. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Germenis AE, Karanikas V. Immunoepigenetics: the unseen side of cancer immunoediting. Immunol Cell Biol. 2007;85(1):55–59. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munn DH, Mellor AL. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and tumor-induced tolerance. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(5):1147–1154. doi: 10.1172/JCI31178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prendergast GC. Immune escape as a fundamental trait of cancer: focus on IDO. Oncogene. 2008;27(28):3889–3900. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takikawa O, Yoshida R, Kido R, Hayaishi O. Tryptophan degradation in mice initiated by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. J Biol Chem. 1986;261(8):3648–3653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfefferkorn ER. Interferon gamma blocks the growth of Toxoplasma gondii in human fibroblasts by inducing the host cells to degrade tryptophan. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81(3):908–912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.3.908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ozaki Y, Edelstein MP, Duch DS. Induction of indoleamine 2,3- dioxygenase: a mechanism of the antitumor activity of interferon gamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(4):1242–1246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.4.1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schefold JC, Zeden JP, Fotopoulou C, et al. Increased indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) activity and elevated serum levels of tryptophan catabolites in patients with chronic kidney disease: a possible link between chronic inflammation and uraemic symptoms. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(6):1901–1908. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pawlak K, Brzosko S, Mysliwiec M, Pawlak D. Kynurenine, quinolinic acid – the new factors linked to carotid atherosclerosis in patients with end-stage renal disease. Atherosclerosis. 2009;204(2):561–566. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kato A, Suzuki Y, Suda T, et al. Relationship between an increased serum kynurenine/tryptophan ratio and atherosclerotic parameters in hemodialysis patients. Hemodial Int. 2010;14(4):418–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2010.00464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laich A, Neurauter G, Widner B, Fuchs D. More rapid method for simultaneous measurement of tryptophan and kynurenine by HPLC. Clin Chem. 2002;48(3):579–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uyttenhove C, Pilotte L, Theate I, et al. Evidence for a tumoral immune resistance mechanism based on tryptophan degradation by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Nat Med. 2003;9(10):1269–1274. doi: 10.1038/nm934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim JW, Nam KH, Ahn SH, et al. Prognostic implications of immunosuppressive protein expression in tumors as well as immune cell infiltration within the tumor microenvironment in gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19(1):42–52. doi: 10.1007/s10120-014-0440-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Theate I, van Baren N, Pilotte L, et al. Extensive profiling of the expression of the indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 protein in normal and tumoral human tissues. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3(2):161–172. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chevolet I, Speeckaert R, Haspeslagh M, et al. Peritumoral indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression in melanoma: an early marker of resistance to immune control? Br J Dermatol. 2014;171(5):987–995. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vanderstraeten A, Luyten C, Verbist G, Tuyaerts S, Amant F. Mapping the immunosuppressive environment in uterine tumors: implications for immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2014;63(6):545–557. doi: 10.1007/s00262-014-1537-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arpinati M, Curti A. Immunotherapy in acute myeloid leukemia. Immunotherapy. 2014;6(1):95–106. doi: 10.2217/imt.13.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choe JY, Yun JY, Jeon YK, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) is frequently expressed in stromal cells of Hodgkin lymphoma and is associated with adverse clinical features: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:335. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Astigiano S, Morandi B, Costa R, et al. Eosinophil granulocytes account for indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-mediated immune escape in human non-small cell lung cancer. Neoplasia. 2005;7(4):390–396. doi: 10.1593/neo.04658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mellor A, Munn D. IDO expression by dendritic cells: tolerance and tryptophan catabolism. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4(10):762–774. doi: 10.1038/nri1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Friberg M, Jennings R, Alsarraj M, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase contributes to tumor cell evasion of T cell-mediated rejection. Int J Cancer. 2002;101(2):151–155. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mellor AL, Munn DH. Tryptophan catabolism and T-cell tolerance: immunosuppression by starvation? Immunol Today. 1999;20(10):469–473. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(99)01520-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Munn DH, Shafzadeh E, Attwood JT, Bondarev I, Pashine A, Mellor AL. Inhibition of T cell proliferation by macrophage tryptophan catabolism. J Exp Med. 1999;189(9):1363–1372. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.9.1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hwu P, Du MX, Lapointe R, Do M, Taylor MW, Young HA. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase production by human dendritic cells results in the inhibition of T cell proliferation. J Immunol. 2000;164(7):3596–3599. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.7.3596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Curti A, Pandolfi S, Valzasina B, et al. Modulation of tryptophan catabolism by human leukemic cells results in the conversion of CD25- into CD25+ T regulatory cells. Blood. 2007;109(7):2871–2877. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-036863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen W, Liang X, Peterson AJ, Munn DH, Blazar BR. The indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase pathway is essential for human plasmacytoid dendritic cell-induced adaptive T regulatory cell generation. J Immunol. 2008;181(8):5396–5404. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chung DJ, Rossi M, Romano E, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-expressing mature human monocyte-derived dendritic cells expand potent autologous regulatory T cells. Blood. 2009;114(3):555–563. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-191197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dubinett S, Sharma S. Towards effective immunotherapy for lung cancer: simultaneous targeting of tumor-initiating cells and immune pathways in the tumor microenvironment. Immunotherapy. 2009;1(5):721–725. doi: 10.2217/imt.09.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Halak BK, Maguire HC, Jr, Lattime EC. Tumor-induced interleukin-10 inhibits type 1 immune responses directed at a tumor antigen as well as a non-tumor antigen present at the tumor site. Cancer Res. 1999;59(4):911–917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suzuki Y, Suda T, Furuhashi K, et al. Increased serum kynurenine/tryptophan ratio correlates with disease progression in lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2010;67(3):361–365. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karanikas V, Zamanakou M, Kerenidi T, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) expression in lung cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6(8):1258–1262. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.8.4446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brandacher G, Perathoner A, Ladurner R, et al. Prognostic value of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression in colorectal cancer: effect on tumor-infiltrating T cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(4):1144–1151. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weiss G, Kronberger P, Conrad F, Bodner E, Wachter H, Reibnegger G. Neopterin and prognosis in patients with adenocarcinoma of the colon. Cancer Res. 1993;53(2):260–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang A, Fuchs D, Winder B, Glover C, Henderson DC, Allen-Mersh TG. Serum tryptophan decrease correlates with immune activation and impaired quality of life in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2002;86(11):1691–1696. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ino K, Yoshida N, Kajiyama H, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase is a novel prognostic indicator for endometrial cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(11):1555–1561. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ino K, Yamamoto E, Shibata K, et al. Inverse correlation between tumoral indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression and tumor-infltrating lymphocytes in endometrial cancer: its association with disease progression and survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2310–2317. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Okamoto A, Nikaido T, Ochiai K, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase serves as a marker of poor prognosis in gene expression profiles of serous ovarian cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(16):6030–6039. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takao M, Okamoto A, Nikaido T, et al. Increased synthesis of indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase protein is positively associated with impaired survival in patients with serous-type, but not with other types of, ovarian cancer. Oncol Rep. 2007;17(6):1333–1339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reibnegger G, Hetzel H, Fuchs D, et al. Clinical significance of neopterin for prognosis and follow-up in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 1987;47(18):4977–4981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Inaba T, Ino K, Kajiyama H, et al. Role of the immunosuppressive enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in the progression of ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;115(2):185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pan K, Wang H, Chen MS, et al. Expression and prognosis role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008;134(11):1247–1253. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0395-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Murr C, Bergant A, Widschwendter M, Heim K, Schrocksnadel H, Fuches D. Neopterin is an independent prognostic variable in females with breast cancer. Clin Chem. 1999;45(11):1998–2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen JY, Li CF, Kuo CC, Tsai KK, Hou MF, Hung WC. Cancer/stroma interplay via cyclooxygenase-2 and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase promotes breast cancer progression. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16(4):410. doi: 10.1186/s13058-014-0410-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yu J, Du W, Yan F, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells suppress antitumor immune responses through IDO expression and correlate with lymph node metastasis in patients with breast cancer. J Immunol. 2013;190(7):3783–3797. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yu J, Sun J, Wang SE, et al. Upregulated expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in primary breast cancer correlates with increase of infiltrated regulatory T cells in situ and lymph node metastasis. Clin Dev Immunol. 2011;2011:469135. doi: 10.1155/2011/469135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weinlich G, Murr C, Richardsen L, Winkler C, Fuchs D. Decreased serum tryptophan concentration predicts poor prognosis in malignant melanoma patients. Dermatology. 2007;214(1):8–14. doi: 10.1159/000096906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Speeckaert R, Vermaelen K, van Geel N, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, a new prognostic marker in sentinel lymph nodes of melanoma patients. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(13):2004–2011. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schroecksnadel K, Winkler C, Fuith LC, Fuchs D. Tryptophan degradation inpatients with gynecological cancer correlates with immune activation. Cancer Lett. 2005;223(2):323–329. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reibnegger GJ, Bichler AH, Dapunt O, et al. Neopterin as a prognostic indicator in patients with carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Cancer Res. 1986;46(2):950–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Inaba T, Ino K, Kajiyama H, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression predicts impaired survival of invasive cervical cancer patients treated with radical hysterectomy. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;117(3):423–428. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu J, Lu G, Tang F, Liu Y, Cui G. Localization of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in human esophageal squamous cell carcinomas. Virchows Arch. 2009;455(5):441–448. doi: 10.1007/s00428-009-0846-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang G, Liu WL, Zhang L, et al. Involvement of indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase in impairing tumor-infiltrating CD8 T-cell functions in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Dev Immunol. 2011;2011:384726. doi: 10.1155/2011/384726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jia Y, Wang H, Wang Y, et al. Low expression of Bin1, along with high expression of IDO in tumor tissue and draining lymph nodes, are predictors of poor prognosis for esophageal squamous cell cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2015;137(5):1095–1106. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Witkiewicz A, Williams TK, Cozzitorto J, et al. Expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma recruits regulatory T cells to avoid immune detection. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206(5):849–854. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Urakawa H, Nishida Y, Nakashima H, Shimoyama Y, Nakamura S, Ishiguro N. Prognostic value of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression in high grade osteosarcoma. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2009;26(8):1005–1012. doi: 10.1007/s10585-009-9290-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wainwright DA, Balyasnikova IV, Chang AL, et al. IDO expression in brain tumors increases the recruitment of regulatory T cells and negatively impacts survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(22):6110–6121. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bonanno G, Mariotti A, Procoli A, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) activity correlates with immune system abnormalities in multiple myeloma. J Transl Med. 2012;10:247. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-10-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chamuleau ME, van de Loosdrecht AA, Hess CJ, et al. High INDO (indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase) mRNA level in blasts of acute myeloid leukemic patients predicts poor clinical outcome. Haematologica. 2008;93(12):1894–1898. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Folgiero V, Goffredo BM, Filippini P, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) activity in leukemia blasts correlates with poor outcome in childhood acute myeloid leukemia. Oncotarget. 2014;5(8):2052–2064. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Corm S, Berthon C, Imbenotte M, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activity of acute myeloid leukemia cells can be measured from patients’ sera by HPLC and is inducible by IFN-gamma. Leuk Res. 2009;33(3):490–494. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hoshi M, Ito H, Fujigaki H, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase is highly expressed in human adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma and chemotherapy changes tryptophan catabolism in serum and reduced activity. Leuk Res. 2009;33(1):39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Masaki A, Ishida T, Maeda Y, et al. Prognostic significance of trypto-phan catabolism in adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(12):2830–2839. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yoshikawa T, Hara T, Tsurumi H, et al. Serum concentration of L-kynurenine predicts the clinical outcome of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. Eur J Haematol. 2010;84(4):304–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2009.01393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ninomiya S, Hara T, Tsurumi H, et al. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in tumor tissue indicates prognosis in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. Ann Hematol. 2011;90(4):409–416. doi: 10.1007/s00277-010-1093-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liu XQ, Lu K, Feng LL, et al. Upregulated expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma correlates with increase of infiltrated regulatory T cells. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013;55:405–414. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.804917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Muller AJ, Du Hadaway JB, Donover PS, Sutanto-Ward E, Prendergast GC. Inhibition of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, an immunoregulatory target of the cancer suppression gene Bin1, potentiates cancer chemotherapy. Nat Med. 2005;11(3):312–319. doi: 10.1038/nm1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hou DY, Muller AJ, Sharma MD, et al. Inhibition of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in dendritic cells by stereoisomers of 1-methyl-tryptophan correlates with antitumor responses. Cancer Res. 2007;67(2):792–801. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Huber C, Batchelor JR, Fuchs D, et al. Immune response-associated production of neopterin. Release from macrophages primarily under control of interferon-gamma. J Exp Med. 1984;160(1):310–316. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.1.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Engin AB, Ozkan Y, Fuchs D, Yardim-Akaydin S. Increased tryptophan degradation in patients with bronchus carcinoma. Eur J Cancer Care. 2010;19(6):803–808. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Xie Q, Wang L, Zhu B, Wang Y, Gu J, Chen Z. The expression and significance of indoleamine -2,3-dioxygenase in non-small cell lung cancer cell. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi. 2008;11(1):115–119. doi: 10.3779/j.issn.1009-3419.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.de Jong RA, Nijman HW, Boezen HM, et al. Serum tryptophan and kynurenine concentrations as parameters for indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activity in patients with endometrial, ovarian, and vulvar cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2011;21:1320–1327. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31822017fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lyon DE, Walter JM, Starkweather AR, Schubert CM, McCain NL. Tryptophan degradation in women with breast cancer: a pilot study. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:156. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sakurai K, Fujisaki S, Nagashima S, et al. Study of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression in patients of thyroid cancer. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2011;38(12):1927–1929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sakurai K, Enomoto K, Amano S, et al. Study of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression in patients of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2004;31(11):1780–1782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sperner-Unterweger B, Neurauter G, Klieber M, et al. Enhanced tryptophan degradation in patients with ovarian carcinoma correlates with several serum soluble immune activation markers. Immunobiology. 2011;216(3):296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sagan D, Kocki T, Kocki J, Sxumilo J. Serum kynurenic acid: possible association with invasiveness of non-small cell lung cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(9):4241–4244. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.9.4741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Munn DH, Sharma MD, Hou D, et al. Expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase by plasmacytoid dendritic cells in tumor-draining lymph nodes. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:280–290. doi: 10.1172/JCI21583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mellor AL, Keskin DB, Johnson T, Chandler P, Munn DH. Cells expressing indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase inhibit T cell responses. J Immunol. 2002;168(8):3771–3776. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.8.3771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cooke DT, Nguyen DV, Yang Y, et al. Survival comparison of adenosquamous, squamous cell, and adenocarcinoma of the lung after lobectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90(3):943–948. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Maeda R, Yoshida J, Ishii G, et al. Risk factors for tumor recurrence in patients with early-stage (stage I and II) non-small cell lung cancer: patient selection criteria for adjuvant chemotherapy according to the 7th edition TNM classification. Chest. 2011;140:1494–1502. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-3279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tomaszek SC, Kim Y, Cassivi SD, et al. Bronchial resection margin length and clinical outcome in non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;40(5):1151–1156. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2011.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dai F, Liu L, Che G, et al. The number and microlocalization of tumor-associated immune cells are associated with patient’s survival time in non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:220. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Watanabe K, Emoto N, Hamano E, et al. Genome structure-based screening identified epigenetically silenced microRNA associated with invasiveness in non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 2011;130(11):2580–2590. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ou X, Cai S, Liu P, et al. Enhancement of dendritic cell-tumor fusion vaccine potency by indoleamine-pyrrole 2,3-dioxygenase inhibitor, 1-MT. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2008;134(5):525–533. doi: 10.1007/s00432-007-0315-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zeng J, Cai S, Yi Y, et al. Prevention of spontaneous tumor development in a ret transgenic mouse model by ret peptide vaccination with indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase inhibitor 1-methyl tryptophan. Cancer Res. 2009;69(9):3963–3970. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Jackson E, Minton SE, Ismail-Khan R, et al. A Phase I Study of 1-Methyl-D-Tryptophan in Combination with Docetaxel in Metastatic Solid Tumors; 2012 ASCO Annual Meeting; 2012. [Accessed June 21, 2017]. suppl; abstr TPS2620. Available from: http://meetinglibrary.asco.org/content/95284-114. [Google Scholar]