Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to explore perceptions of patients with rheumatic diseases treated with subcutaneous (SC) biological drugs on the impact on daily life and satisfaction with current therapy, including preferred attributes.

Methods

A survey was developed ad hoc by four rheumatologists and three patients, including Likert questions on the impact of disease and treatment on daily life and preferred attributes of treatment. Rheumatologists from 50 participating centers were instructed to handout the survey to 20 consecutive patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), axial spondyloarthritis (ax-SpA), or psoriatic arthritis (PsA) receiving SC biological drugs. Patients responded to the survey at home and sent it to a central facility by prepaid mail.

Results

A total of 592 patients returned the survey (response rate: 59.2%), 51.4% of whom had RA, 23.8% had ax-SpA, and 19.6% had PsA. Patients reported moderate-to-severe impact of their disease on their quality of life (QoL) (51.9%), work/daily activities (49.2%), emotional well-being (41.0%), personal relationships (26.0%), and close relatives’ life (32.3%); 30%–50% patients reported seldom/never being inquired about these aspects by their rheumatologists. Treatment attributes ranked as most important were the normalization of QoL (43.6%) and the relief from symptoms (35.2%). The satisfaction with their current antirheumatic therapy was high (>80% were “satisfied” or “very satisfied”), despite moderate/severe impact of disease.

Conclusion

Patients with rheumatic diseases on SC biological therapy perceive a high disease impact on different aspects of daily life, despite being highly satisfied with their treatment; the perception is that physicians do not frequently address personal problems. Normalization of QoL is the most important attribute of therapies to patients.

Keywords: rheumatic diseases, quality of life, emotional well-being, biological drugs, patient’s satisfaction

Introduction

Rheumatic diseases are among the most common chronic diseases, being a major cause of disability in developed countries and consuming a large amount of health care and social resources.1,2 Rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriatic arthritis (PsA), and axial spondyloarthritis (ax-SpA) have a chronic course, requiring lifelong management and causing a negative impact on quality of life (QoL).3,4 QoL in rheumatic diseases is determined not only by clinical symptoms but also by physical and social functioning.5,6 In turn, impaired health-related QoL and physical function are directly related to the socioeconomic impact of the disease.7 In addition, rheumatic diseases impact highly on emotional well-being, fact frequently overseen by rheumatologists.8 For these reasons, assessing the QoL and its determinants as well as the impact of disease and treatment on patients’ daily life is important.

The availability of biological therapies has proven enormous benefits in attaining a better disease control and, consequently, improving the functional capacity and QoL of patients with RA, PsA, and ax-SpA.9–11 However, the efficacy of these drugs is still limited and the percentage of patients achieving a normal QoL is still insufficient.9–11 Although validated instruments are available to measure different aspects of QoL, information directly obtained from patients through surveys can give complementary information on aspects that validated questionnaires do not usually address. With the aim of exploring patients’ perceptions on the burden of rheumatic diseases in their daily life and their expectations and satisfaction with the antirheumatic therapy, we implemented a survey to patients with rheumatic diseases treated with subcutaneous (SC) biological drugs.

Methods

RHEU-LIFE was a survey launched in September and October 2015. Patients were eligible if they were adults with a diagnosis of one of the three target diseases, namely RA, ax-SpA, and PsA, and were being treated with SC biological drugs at the time of the survey and at least since the last medical appointment, and were able to understand and respond the survey in the opinion of the treating rheumatologist. Patients being prescribed a first biological drug as of the survey date were not eligible. Rheumatologists from 50 participating centers were instructed to handout a printed survey to the first 20 consecutive patients attending their outpatient clinics who fulfilled the selection criteria, regardless of age, gender, disease severity, or duration of disease.

Patients received a closed envelope with the printed survey, and a cover letter explaining its purpose and clarifying the anonymous and voluntary nature of the survey. Patients were instructed to respond at home and to return the completed form directly to a central facility by prepaid mail. No reminders were sent to patients, and no clinical data were collected by physicians from patients’ clinical records.

The questions included in the survey were developed by four rheumatologists and reviewed and discussed in full by three patient representatives from the Spanish umbrella association of arthritis patients, Coordinadora Nacional de Artritis (ConArtritis), ensuring the appropriateness of the questions and the language used. The final survey contained 54 multiple-choice items exploring the following aspects: perception on the impact of disease on daily life, sources of information on disease and treatments, expectations from medications, satisfaction with current treatment and with specific features of treatment, and some logistical aspects on dispensation of their SC medication and follow-up.

The impact of disease on daily life was explored through different aspects: QoL in general, emotional well-being, work or daily activities, personal relationships, and family life. For each of these aspects, patients selected one of the four closed options: “no impact”, “mild”, “moderate”, and “severe impact”. Patients were also requested to respond how frequently their treating physicians discussed the above-mentioned topics with them (response categories: “always or nearly always”, “frequently”, “only sometimes”, and “never or seldom”). With regard to what patients expect from treatments, patients were requested to rank the importance, from 1 (the most important) to 5 (the less important), of the following attributes: control of symptoms, tolerability, speed of action, easiness of use, and normalization of QoL. For each attribute, patients were requested to rate the level of satisfaction with their current therapy (response categories: “very satisfied”, “satisfied”, “neutral [neither satisfied nor unsatisfied]”, “unsatisfied”, or “very unsatisfied”). The whole content of the survey is provided as Supplementary material.

Ethical considerations

The survey and the working procedures were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Gregorio Marañón University Hospital, Madrid, Spain, and by the Spanish association of patients with arthritis, ConArtritis. The survey included an instruction page for patients in which the anonymous and voluntary nature of the survey was described. Thus, return of completed questionnaires was considered implied consent to participate.

Statistical considerations

Due to the exploratory nature of the study, no formal hypothesis or prespecified sample size was set and no imputation was made for missing values. Quantitative variables are expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD), or median and interquartile range (IQR) if data were not distributed normally; qualitative variables are described as absolute and relative frequencies.

The influence of by age, gender, diagnosis, duration of the disease (>10 or <10 years), and source of care (self-care versus support from others) on perceived impact of disease was analyzed by chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests. Comparisons of several subgroups were made using the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test. The association of variables to perceived impact was analyzed with multivariate logistic regression, and results presented as odd ratio with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). In the models, the dependent variables were dichotomized responses of the items (“severe/moderate” versus “mild/none”) and the explanatory variables included age (in quartiles), gender, diagnosis (RA, PsA, and ax-SpA), disease duration (above or below the median), and source of care (support from others versus self-care). Given the descriptive nature of the results, no multiplicity adjustments were made. A P-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was done using the SPSS program Version 18.0.0.

Results

Response rate and sample description

The survey was handed to 1,000 patients and was returned by 592 (response rate 59.2%). The mean age of the respondents was 41.7 years (SD 13.1), and 57.6% of them were females. The highest educational level achieved by the respondents was university or higher in 23.0%, technical studies in 13.6%, and elementary school in 54.8%; 8.3% referred no formal studies. Regarding work-related variables, 42.5% were actively working, 13.0% were housekeepers, 20.3% were retired, 7.0% were unemployed, and 14.2% were on sick leave (2.7% temporal leave, 9.5% permanent leave due to their rheumatic disease, and 1.9% leave due to other reasons). The distribution of rheumatic diseases was 304 RA (51.4%), 141 ax-SpA (23.8%), and 116 PsA (19.6%); thirty-one patients (5.2%) did not identify their disease. The median disease duration was 10 years (P25–75: 5–18). The SC biological drug was the first biological drug for 60.4% of the patients, the second for 26.1% of the patients, and the third or successive for 13.5% of the patients.

Impact of the rheumatic disease in daily life

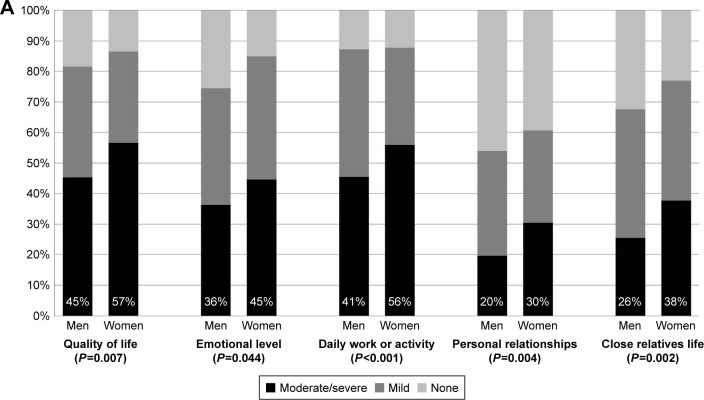

Table 1A shows the perceived impact of the rheumatic disease on different spheres of daily life. QoL and daily work or activity were the items on which patients described the highest perceived impact, with ~50% of patients reporting moderate-to-severe impact. The impact on the different spheres did not differ significantly by diagnosis. Females tended to perceive higher levels of impact than males in all spheres (P<0.05 for all the comparisons; Figure 1A). Similarly, patients with the duration of disease above the median (≥10 years; Figure 1B) and older patients reported higher levels of perceived impact than their counterparts. Finally, those whom others cared for reported higher impact of disease on personal relationships and on close relatives’ lives than those who took care of themselves (Figure 1C).

Table 1.

Perceived impact of the rheumatic disease on daily life domains and associated variables

| (A) Percentage of patients responding to “how much do you consider your rheumatic disease impacts your…?”

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | |

| Quality of life (n=569) (%) | 15.6 | 32.5 | 32.2 | 19.7 |

| Emotional well-being (n=571) (%) | 19.3 | 39.8 | 26.6 | 14.4 |

| Daily work or activities (n=565) (%) | 16.3 | 34.5 | 28.0 | 21.2 |

| Personal relationships (n=570) (%) | 41.8 | 32.3 | 17.2 | 8.8 |

| Family (close relatives) life (n=570) (%) | 27.2 | 40.5 | 20.2 | 12.1 |

| (B) Multivariable analysis of factors associated to perceived impact (“moderate/severe” versus “none/mild”) on different aspects of daily life

| ||

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Quality of life | ||

| Age (per quartile increase) | 1.30 (1.08–1.58) | 0.006 |

| Female gender (versus male) | 1.62 (1.07–2.47) | 0.024 |

| PsA (versus RA) | 1.76 (1.04–2.97) | 0.034 |

| Disease duration ≥10 years (versus <10 years) | 1.72 (1.14–2.59) | 0.009 |

| Emotional well-being | ||

| Female gender (versus male) | 1.74 (1.14–2.67) | 0.024 |

| PsA (versus RA) | 1.66 (0.99–2.77) | 0.055 |

| Disease duration ≥10 years (versus <10 years) | 1.87 (1.24–2.87) | 0.003 |

| Daily work or activities | ||

| Age (per quartile increase) | 1.29 (1.07–1.56) | 0.009 |

| Female gender (versus male) | 1.91 (1.25–2.90) | 0.003 |

| Axial SpA (versus RA) | 1.61 (0.97–2.66) | 0.066 |

| Disease duration ≥10 years (versus <10 years) | 1.53 (1.02–2.31) | 0.041 |

| Personal relationships | ||

| Female gender (versus male) | 1.90 (1.61–3.11) | 0.003 |

| Axial SpA (versus RA) | 1.74 (0.98–3.09) | 0.060 |

| PsA (versus RA) | 1.73 (0.97–3.10) | 0.065 |

| Disease duration ≥10 years (versus <10 years) | 1.93 (1.19–3.12) | 0.008 |

| Care from others (versus only self-care) | 1.37 (1.08–1.74) | 0.010 |

| Family (close relatives) life | ||

| Age (per quartile increase) | 1.20 (0.97–1.47) | 0.092 |

| Female gender (versus male) | 2.01 (1.28–3.29) | 0.003 |

| Disease duration ≥10 years (versus <10 years) | 2.01 (1.27–3.12) | 0.003 |

| Care from others (versus only self-care) | 1.57 (1.25–1.98) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SpA, spondyloarthritis.

Figure 1.

Perceived impact of rheumatic disease, by gender (A), disease duration (B), and source of care (C).

Note: Bottom numbers in bars represent the percentage of patients reporting that their rheumatic disease has a moderate-to-severe impact on different aspects of daily life.

The resulting models of factors associated with perceived impact are displayed in Table 1B. Female gender and disease duration were associated with “severely/moderately” perceived impact on all daily life spheres. Older age and diagnosis (PsA or SpA versus RA) were associated with worse perception in several spheres, and care by others was associated with impact on patients’ personal relationships and close relatives’ lives.

The vast majority of patients agreed that, during the medical interview, their rheumatologists inquire them always or frequently about their symptoms (95.8%) and about their QoL (75.7%). However, rheumatologists much rarely inquired about emotional well-being, work or daily activities, or personal relationships (Table 2).

Table 2.

Rheumatologists’ behavior as perceived by patients

| Always/nearly always | Frequently | Only sometimes | Never/seldom ever | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inquires about my symptoms (n=539) (%) | 77.2 | 18.6 | 3.3 | 0.9 |

| Inquires about how my disease affects my quality of life (n=526) (%) | 50.0 | 25.7 | 16.2 | 8.2 |

| Inquires about how my disease affects my emotional well-being (n=519) (%) | 37.4 | 24.3 | 17.5 | 20.8 |

| Inquires about how my disease affects my daily work or activities (n=520) (%) | 43.7 | 24.8 | 17.7 | 13.8 |

| Inquires about how my disease affects my personal relationships (n=513) (%) | 32.0 | 18.5 | 18.9 | 30.6 |

Note: Frequency with which rheumatologists inquire patients about different aspects of their lives during clinical visits.

Satisfaction with their current therapy and treatment attributes preferred by patients

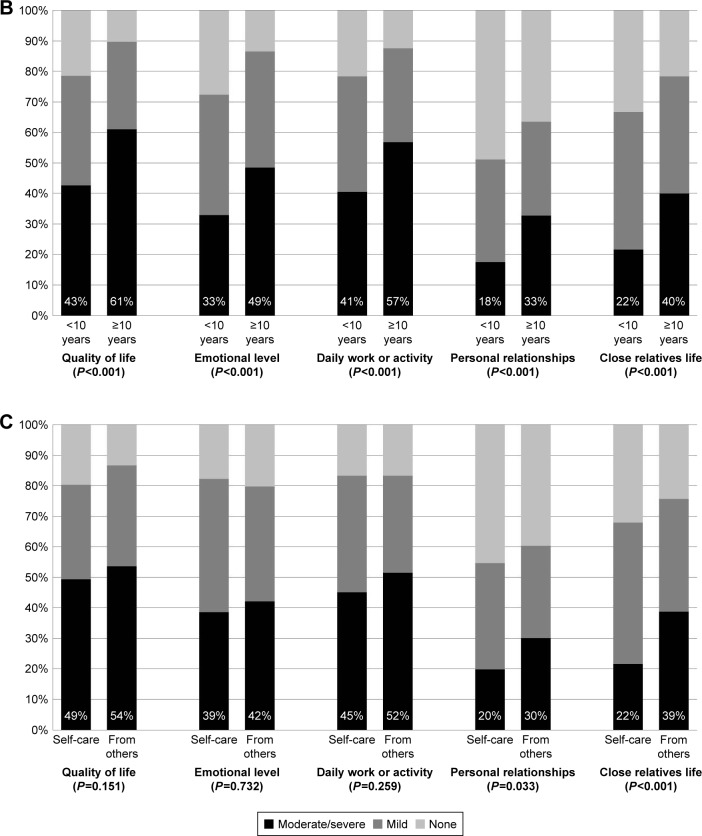

The attribute most frequently mentioned as the most important for patients (more frequently ranked as 1) was that the medication helped normalizing QoL (43.6%), followed by the control of symptoms (35.2%); other attributes were mentioned less frequently (Figure 2). Gender and diagnosis did not show an association with the attribute raking. Also, there were no differences in the preferred attributes with regard to the number of biological drugs administered previously (first, second, and third or successive) (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Patients’ attribution of importance to each treatment feature.

Note: Results are expressed in percentage of respondents.

Abbreviation: QoL, quality of life.

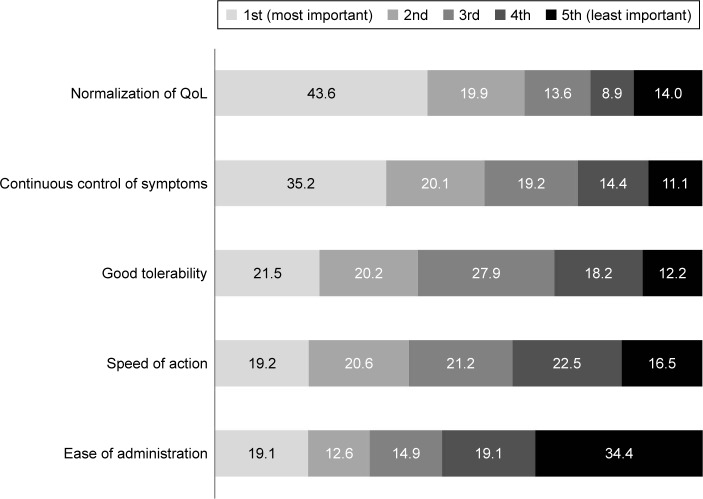

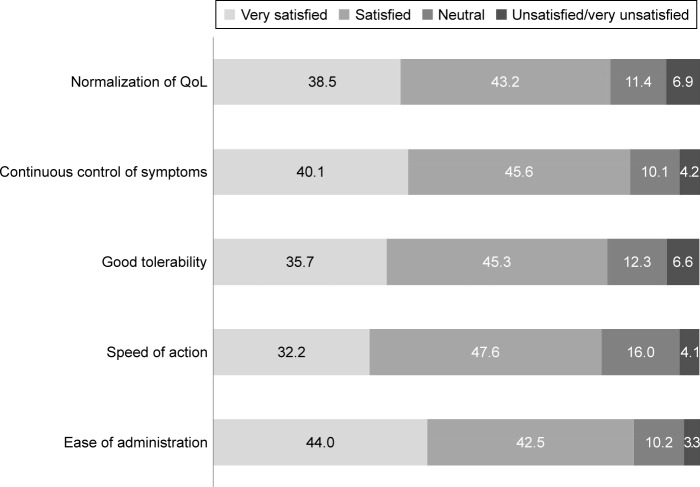

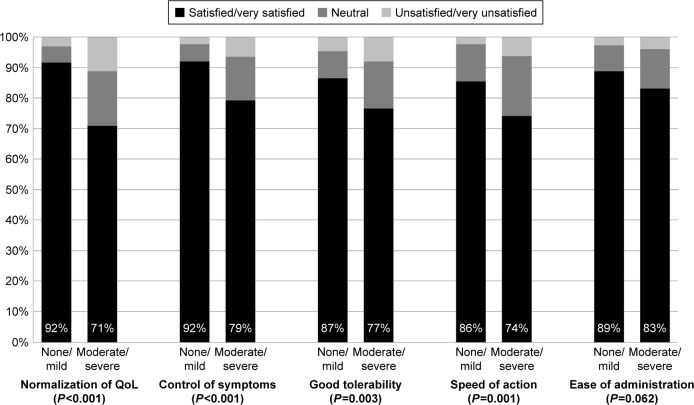

Overall, patients reported to be highly satisfied with their current antirheumatic therapy, with >80% being satisfied or very satisfied with each of the abovementioned attributes (Figure 3); and only ~5% reporting “unsatisfied” or “very unsatisfied”. Similar figures were seen for males and females. The percentage of patients satisfied was higher among those patients perceiving none or mild impact of disease than among those perceiving moderate-to-severe impact (Figure 4); however, the level of satisfaction with treatment was not low among patients with moderate-to-severe impact of disease, with >70% reporting being satisfied or very satisfied (Figure 4). The percentage of patients satisfied or very satisfied was higher among those patients treated with the first SC biological drug than among those treated with the second, third, or successive drugs for the normalization of QoL (85.7, 76.8, and 72.0%, respectively, P=0.007), the control of symptoms (87.8, 84.2, and 78.4%, respectively, P=0.097), and speed of action (83.5, 74.2, and 73.2%, respectively, P=0.046) and similar for the tolerability and easiness of administration.

Figure 3.

Patients’ satisfaction with current antirheumatic therapy.

Notes: Bars represent the percentage of patients into each category for the different features. Note that, for space reasons, the categories “unsatisfied” and “very unsatisfied” have been combined in the figure.

Abbreviation: QoL, quality of life.

Figure 4.

Patients’ satisfaction with current antirheumatic therapy, by the perception on impact on quality of life (moderate/severe versus none/mild).

Note: Bottom numbers in bars represent the percentage of patients reporting being satisfied or very satisfied with each treatment aspect.

Abbreviation: QoL, quality of life.

Discussion

Rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases have been ranked as the second largest contributor to years lived with global disability,12 and rheumatic patients exhibit an impaired QoL compared to the general population and other chronic conditions.3,4 Our results contribute by adding patients’ perspective on how the disease impacts not only QoL but also emotional well-being, daily activities, their relationships, and the lives of their families, topics that, they report, are not frequently discussed with their treating physicians. From the multivariable models, we conclude that several differences exist with regard to age, gender, and the disease itself. Also, patients who need care from others acknowledge the impact of their disease in their close relatives. Patients prefer that drug therapies contribute to normalize QoL and control clinical symptoms over tolerability or easiness of administration, which also arise as important therapy attributes, and express a high level of satisfaction with their current therapies.

Advanced age and female gender were associated with “moderate-to-severe” perceived impact on all daily life spheres. This was also found using the EuroQol 5D (EQ-5D) utility index in a recent study on patients with different rheumatic diseases from rheumatology outpatient clinics.13 Several studies have described a poorer response to pharmacological treatments of females than males with RA14,15 or SpA.16,17 Similarly, male gender has been found to be predictive for both response (BASDAI 50, ASAS 20, and ASAS 40) and treatment continuation in ax-SpA.16,17 While this can contribute to reduce QoL in females with regard to males, it has also been hypothesized that female patients score higher on subjective measures of disease activity specific to musculoskeletal performance, probably due to a general tendency toward reporting poorer scores in questionnaires.17 Our finding that older patients and those with longer disease duration perceive higher impact of their rheumatic disease on daily life is congruent with previous reports.13 Also, our finding of a 14.2% of patients in sick leave is in line with the high proportion of patients describing moderate/severe impairment of QoL, emotional well-being, and work/daily activities, and it is not surprising in a sample of patients treated with biological drugs, with a median disease duration self-reported of 10 years.

In the RHEU-LIFE survey, patients acknowledge the impact of their disease on their personal relationships and on their close relatives’ lives; moreover, those who need support from others for their care rated worse in all items. Successful self-management interventions in patients with chronic illnesses require an integrated approach with implication not only of the patient and the health professional but also from the patient social environment: family, friends, and colleagues.18–20 Self-management support might be hampered by patients’ circumstances, such as depression, and also by poor physician communication or low family support.21 In this regard, patients’ responses to this survey show that, during clinical visits, physicians focus their questions on clinical symptoms, but a significant percentage never, or only sometimes, ask their patients about how the disease affects their emotional well-being or their personal relationships, when these are aspects of daily life that patients have debilitated. The journey toward patient-centered health care models that integrate the perspectives and preferences of patients into the delivery of health care entails an effective patient–physician partnership taking into account the individual patients values, needs, and life context (eg, home life, job, and family relationships) for decisions.22

Our survey also shows that the attributes of treatment most valued by patients – normalization of QoL and control of symptoms – are consistent with regarding QoL as a major target and patients’ preferences might be affected by this view. Notably, patients were satisfied with their medications even if they had serious impact of their diseases on their lives. This may indicate, on one hand, that medications are efficacious to relief symptoms and to improve QoL, but on the other hand, it could also indicate that patients get accustomed to living with certain degree of symptoms and QoL impairment. Thus, setting expectations and objectives with patients is important and can contribute toward achieving better clinical outcomes.

Our study has several limitations. No clinical data were collected from clinical charts, so that “objective” activity could not be tested against perceived impact. Also, previous or current specific treatments were not recorded so that we could not study the effect of these on responses. In addition, the survey was distributed to patients treated with SC biological drugs, what could be a selected group of severe patients, what precludes a generalization of our results to the more general population of patients with rheumatic diseases. The consecutive sampling of patients could also lead to a selection of more severe patients. Nevertheless, this is the group of patients who can be more disrupted by the rheumatic disease and in which implementing specific actions can be more efficient. We also need taking into account that, as a survey, it did not follow a formal validation process as validated questionnaires use to follow. Although this is a limitation, the validity of the information obtained lays on the fact that the content was generated with and reviewed by patients and the survey responds to what patients thought was important for them. Finally, as the survey was anonymous, the characteristics of the patients who did not respond to the survey are unknown, and because the survey was carried out in Spain, the results might not be generalizable to patients from different countries or cultures.

Conclusion

With all these limitations, perceptions from patients are always relevant for a patient-centered approach in health care. In this context, surveys like the present provide valuable additional information to that provided by clinical studies. Outpatients with rheumatic diseases under treatment with SC biological drugs describe a strong negative impact of their disease on different spheres of their daily life and in their relatives, but some of these topics are not addressed by the treating physician during clinical appointments. Consistent with the impact of patients’ perceive, they consider the improvement of QoL and the relief from symptoms as the most important attributes of therapies and show a high degree of satisfaction with the treatments they follow, which suggests that drugs are efficacious but also that patients get accustomed to tolerate certain disease burden. Addressing all these aspects from a comprehensive perspective is important for a patient-centered approach aiming to reduce the impact of the rheumatic diseases on patients’ daily life.

Acknowledgments

The RHEU-LIFE survey was reviewed and endorsed by the Spanish Association of Patients with Arthritis (Coordinadora Nacional de Artritis; ConArtritis) and funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme of Spain, a subsidiary of Merck & Co, Kenilworth, NJ, USA. The following health care professionals contributed to the RHEU-LIFE project by inviting patients to participate and explaining and handing the survey to their patients (in alphabetical order): Pilar Ahijado Guzmán (Hospital Infanta Elena, Madrid), Javier Alegre López (Hospital Universitario de Burgos), Andrés Ariza Hernández (Hospital General de Ciudad Real), Emilia Aznar (Hospital Lozano Blesa, Zaragoza), Joaquín Belzunegui (Hospital Universitario de Donostia, San Sebastián), Daniel Batista Perdomo (Hospital Insular, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria), Juan Carlos Bermell Serrano (Hospital Virgen de la Luz, Cuenca), Pilar Bernabeu (Hospital San Juan, Alicante), María Bonet (Hospital l’Alt Penedés, Vilafranca), Vanesa Calvo del Río (Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander), Benita Cardona Natta (Hospital Mateu Orfila, Menorca), Carmen Carrasco Cubero (Hospital Universitario Infanta Cristina, Badajoz), Natalia Casasnovas Pons (Centro de Salud Canal Salat, Menorca), Iván Castellvi (Hospital l’Alt Penedés, Vilafranca), Rosa Castillo Montalvo (Hospital Universitario de Guadalajara), Virginia Coret Cagigal (Hospital Carlos Haya, Málaga), Ana Cruz Valenciano (Hospital Severo Ochoa, Madrid), Carlos Fernández López (Hospital Universitario A Coruña), Fernando Gamero Ruiz (Hospital Virgen del Puerto, Plasencia), Blanca García (Hospital San Jorge, Huesca), Rosa García Portales (Hospital Virgen de la Victoria, Málaga), Javier R Godo (Especialista en Reumatología, Madrid), Antonio Gómez (Hospital Parc Taulí, Sabadell), Amparo Gómez Cañadas (Hospital Mutua de Terrassa), Silvia Iniesta Escolano (Hospital del Mar, Barcelona), Ana María Jiménez (Hospital Infanta Sofía, Madrid), Cristina Lerín Lozano (Hospital Manacor, Mallorca), Juan José Lerma (Hospital General de Castellón), María López Lasanta (Hospital Vall d’Hebrón, Barcelona), Pilar Morales Garrido (Hospital Virgen de las Nieves, Granada), Estefanía Moreno (Hospital l’Alt Penedés, Vilafranca), María José Moreno (Hospital Rafael Méndez, Lorca), Jose Antonio Mosquera (Complejo Hospitalario de Pontevedra), Alejandro Muñoz Jiménez (Hospital Virgen del Rocío, Sevilla), Cristóbal Núñez-Cornejo (Hospital Universitario La Fe, Valencia), Alejandro Olivé (Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol, Barcelona), Carmen Ordás Calvo (Hospital de Cabueñes, Gijón), Rafaela Ortega Castro (Hospital Reina Sofía, Córdoba), Fred Antón Pagés (Hospital Río Carrión, Palencia), Eva Pérez Pampín (Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Santiago de Compostela), Lucía Pantoja Zarza (Hospital del Bierzo, León), Manuel Riesco Díaz (Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez, Huelva), Fernando Rodríguez (Hospital Santa Lucía, Cartagena), Sergio Rodríguez Montero (Hospital Nuestra Señora de Valme, Sevilla), Ana Rubial (Hospital de Txagorrituxu, Alava), Carmen Rusiñol (Hospital Mútua de Terrassa), Celia Saura Demur (Hospital Clinic, Barcelona), Beatriz Tejera Segura (Hospital Universitario La Laguna, Tenerife), Carlos Tomás (Hospital Mora d’Ebre, Tarragona), Carmelo Tornero (Hospital Morales Meseguer, Murcia), Pilar Trenor (Hospital Clínico de Valencia), Larissa Valor (Hospital Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Madrid), and Amparo Ybáñez (Hospital Dr Peset, Valencia).

Footnotes

Disclosure

MJA and LC-C are full employees at Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD) of Spain. The rest of the authors received honoraria from MSD, Spain, as advisors for the design, implementation, and data interpretation of the survey. CMG has received honoraria for lectures for MSD, Spain. EB-G has served as a consultant for BMS, Roche, and MSD, Spain, and has received honoraria for lectures or educational presentations for Abbvie, UCB, Roche, Pfizer, and BMS. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Badley EM, Rasooly I, Webster GK. Relative importance of musculoskeletal disorders as a cause of chronic health problems, disability, and health care utilization: findings from the 1990 Ontario Health Survey. J Rheumatol. 1994;21(3):505–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yelin E, Callahan LF. The economic cost and social and psychological impact of musculoskeletal conditions. National Arthritis Data Work Groups. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38(10):1351–1362. doi: 10.1002/art.1780381002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alonso J, Ferrer M, Gandek B, et al. IQOLA Project Group Health-related quality of life associated with chronic conditions in eight countries: results from the International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) Project. Qual Life Res. 2004;13(2):283–298. doi: 10.1023/b:qure.0000018472.46236.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sprangers MA, de Regt EB, Andries F, et al. Which chronic conditions are associated with better or poorer quality of life? J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(9):895–907. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00204-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kvien TK, Uhlig T. Quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2005;34(5):333–341. doi: 10.1080/03009740500327727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salaffi F, Carotti M, Gasparini S, Intorcia M, Grassi W. The health-related quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and psoriatic arthritis: a comparison with a selected sample of healthy people. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:25. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ara RM, Packham JC, Haywood KL. The direct healthcare costs associated with ankylosing spondylitis patients attending a UK secondary care rheumatology unit. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47(1):68–71. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anyfanti P, Gavriilaki E, Pyrpasopoulou A, et al. Depression, anxiety, and quality of life in a large cohort of patients with rheumatic diseases: common, yet under treated. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35(3):733–739. doi: 10.1007/s10067-014-2677-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Machado MA, Barbosa MM, Almeida AM, et al. Treatment of ankylosing spondylitis with TNF blockers: a meta-analysis. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33(9):2199–2213. doi: 10.1007/s00296-013-2772-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh JA, Christensen R, Wells GA, et al. A network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of biologics for rheumatoid arthritis: a Cochrane overview. CMAJ. 2009;181(11):787–796. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ash Z, Gaujoux-Viala C, Gossec L, et al. A systematic literature review of drug therapies for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis: current evidence and meta-analysis informing the EULAR recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(3):319–326. doi: 10.1136/ard.2011.150995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2163–2196. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anyfanti P, Triantafyllou A, Panagopoulos P, et al. Predictors of impaired quality of life in patients with rheumatic diseases. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35(7):1705–1711. doi: 10.1007/s10067-015-3155-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jawaheer D, Olsen J, Hetland ML. Sex differences in response to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in early and established rheumatoid arthritis – results from the DANBIO registry. J Rheumatol. 2012;39(1):46–53. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hyrich KL, Watson KD, Silman AJ, Symmons DP, British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register Predictors of response to anti-TNF-alpha therapy among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45(12):1558–1565. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arends S, Brouwer E, van der Veer E, et al. Baseline predictors of response and discontinuation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha blocking therapy in ankylosing spondylitis: a prospective longitudinal observational cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13(3):R94. doi: 10.1186/ar3369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glintborg B, Ostergaard M, Krogh NS, Dreyer L, Kristensen HL, Hetland ML. Predictors of treatment response and drug continuation in 842 patients with ankylosing spondylitis treated with anti-tumour necrosis factor: results from 8 years’ surveillance in the Danish nationwide DANBIO registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(11):2002–2008. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.124446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barlow J, Wright C, Sheasby J, Turner A, Hainsworth J. Self-management approaches for people with chronic conditions: a review. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48(2):177–187. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holman H, Lorig K. Patient self-management: a key to effectiveness and efficiency in care of chronic disease. Public Health Rep. 2004;119(3):239–243. doi: 10.1016/j.phr.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carryer J, Budge C, Hansen C, Gibbs K. Providing and receiving self-management support for chronic illness: patients’ and health practitioners’ assessments. J Prim Health Care. 2010;2(2):124–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jerant AF, von Friederichs-Fitzwater MM, Moore M. Patients’ perceived barriers to active self-management of chronic conditions. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57(3):300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Voshaar MJ, Nota I, van de Laar MA, van den Bemt BJ. Patient-centred care in established rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2015;29(4–5):643–663. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]