Abstract

Optic gliomas are brain tumors characterized by slow growth, progressive loss of vision, and limited therapeutic options. Optic gliomas contain various amounts of myxoid matrix, which can represent most of the tumor mass. We sought to investigate biological function and protein structure of the myxoid matrix in optic gliomas to identify novel therapeutic targets. We reviewed histological features and clinical imaging properties, analyzed vasculature by immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy, and performed liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry on optic gliomas, which varied in the amount of myxoid matrix. We found that although subtypes of optic gliomas are indistinguishable on imaging, the microvascular network of pilomyxoid astrocytoma, a subtype of optic glioma with abundant myxoid matrix, is characterized by the presence of endothelium-free channels in the myxoid matrix. These tumors show normal perfusion by clinical imaging and lack histological evidence of hemorrhage organization or thrombosis. The myxoid matrix is composed predominantly of the proteoglycan versican and its linking protein, a vertebrate hyaluronan and proteoglycan link protein 1. We propose that pediatric optic gliomas can maintain blood supply without endothelial cells by using invertebrate-like channels, which we termed primitive myxoid vascularization. Enzymatic targeting of the proteoglycan versican/hyaluronan and proteoglycan link protein 1 rich myxoid matrix, which is in direct contact with circulating blood, can provide novel therapeutic avenues for optic gliomas of childhood.

Optic gliomas are low-grade astrocytic tumors of the optic pathway and occur predominantly in children and young adults. The factors driving the behavior of optic gliomas remain unknown. The genetic landscape of this tumor subtype is relatively homogeneous and insufficient to explain the diverse phenotypes and unpredictable clinical courses observed.1, 2 It is possible that the tumor microenvironment plays an important role in the development of optic gliomas, but in contrast to malignant gliomas, angiogenesis is not associated with poor outcomes. Optic gliomas typically grow slowly, and may lead to loss of vision, endocrine deficiencies, and neurological impairment. The role of surgery is limited because of the critical location and infiltrative growth pattern of optic gliomas. Other treatment modalities, including chemotherapy and radiation therapy, carry significant morbidity and often fail to provide tumor control. Optic gliomas are composed of two distinct histological subtypes, pilocytic astrocytoma (PA) and pilomyxoid astrocytoma (PMXA).3 Abundant bluish chondroid myxoid matrix, after hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, is characteristic of PMXA but not PA, and typically accounts for >50% of tumor volume. The biological role of the matrix protein composition or its effect on tumor growth and angiogenesis in PMXA is currently unknown. Interestingly, PAs are commonly diagnosed throughout the brain, whereas PMXAs arise almost exclusively in the optic tract, suggesting a role of optic tract microenvironment in the development of this particular subtype of low-grade gliomas. The prognostic significance of the myxoid matrix remains unknown, partially because of a large number of tumors with intermediate features containing some myxoid matrix but not fulfilling all the criteria for diagnosis of PMXA. The absence of clear prognostic value of pilomyxoid features recently led to changing the grade of PMXA from World Health Organization (WHO) grade II, and the current recommendation is not to assign a WHO grade.3

Endothelial cells are necessary for angiogenesis in vertebrates, but not in invertebrates.4 Hypoxia is a strong stimulator of angiogenesis in tumors and is driven largely by vascular endothelial growth factor A secretion. Vascular endothelial growth factor A mediates vasculogenesis by recruiting endothelial progenitors from circulating bone marrow–derived cells.5, 6 Vascular endothelial growth factor A–driven vascular proliferation is a hallmark of malignant gliomas and is associated with aggressive tumor behavior and poor survival.3 During evolution, three major types of circulatory system developed in metazoans: hemal, hemocoelic, and endothelial system. Although vertebrates have a closed endothelial circulatory system and endothelial cells represent a key element of vascular anatomy, the hemal and hemocoelic systems of invertebrates lack endothelial cells. The hemal system of invertebrates consists of a network of spaces lined by basement membranes internally and endodermal or mesodermal epithelial lining on the opposite side.7, 8 In the hemocoelic system, the hemal system opens to the coelomic cavity and blood freely circulates around the organs, which is frequently associated with disappearance of the coelomic epithelium.4, 7 The question of whether human tumors can develop alternative, invertebrate-like, mechanisms for obtaining blood supply led us to discover a biologically novel endothelium-independent mechanism of tumor vascularization distinct from the mechanism of conventional vertebrate angiogenesis.

Currently, there are no non-Nf1 murine models of optic glioma or pilomyxoid astrocytoma. Because of the inability of genomic analysis to explain the differences between pilocytic and pilomyxoid astrocytomas, we chose a proteomic-based approach to identify both structure and biology of the myxoid matrix. Herein, we show that pediatric optic pathway gliomas maintain their blood supply and neoplastic cell growth independent of endothelialized blood vessels. Using high-throughput proteomic analysis, we describe, for the first time, the protein structure of the myxoid matrix in optic gliomas and identify potential extracellular matrix targets for therapy of this disease.

Materials and Methods

Clinical Data and Imaging

Clinical information was obtained from the medical records on 120 patients diagnosed as having optic glioma at New York University between 1996 and 2014 after obtaining Institutional Review Board approval. Axial T2, precontrast, and post-contrast T1 weighted magnetic resonance images were reviewed by two investigators (R.J. and B.C.). Diameters, margins, heterogeneity, and percentage of the contrast enhancement, extent of edema, and presence or absence of susceptibility, cysts, necrosis, and hemorrhage were evaluated. Perfusion was evaluated where available. Because of the changes in imaging techniques, a complete set of comparable clinical imaging studies was available for 10 optic gliomas.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Histological features of the samples were evaluated by two neuropathologists (M.S. and D.Z.) using standard, clinical H&E staining. Following clinically approved protocols, the following antibodies were used for immunohistochemical analysis of 12 optic gliomas for which sufficient tissue was available: CD34, prediluted (catalog number 790-2927; Ventana Medical Systems, Tuscon, AZ); Erg, prediluted (catalog number 790-4576; Ventana Medical Systems); GLUT-1, prediluted (catalog number 355A-18; Cell Marque, Rocklin CA); CA-IX, prediluted (catalog number 379M-18; Cell Marque); and Ki-67, prediluted (catalog number 790-4286; Ventana Medical Systems). Microvascular density was assessed as described previously9 and presented as number of blood vessels per mm2. The proliferation rate was calculated as a ration of Ki-67–positive cells after 500 total tumor cells were counted. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. The principal statistical test was the t-test (two-tailed with unequal variance). We considered a value of P < 0.05 to be statistically significant. The Versican isoform V1 expression was confirmed using anti-Versican antibody (ab19345) from Abcam (Cambridge, MA) after heat-induced antigen retrieval (dilution, 1:100).

Electron Microscopy

Three optic pilomyxoid astrocytomas had tissue collected at the time of surgery for electron microscopy studies. Specimens for electron microscopy were fixed in phosphate-buffered 1% glutaraldehyde/4% paraformaldehyde, post-fixed in 1% osmium teroxide, and embedded in epoxy resin in a standard manner. Scout sections (1 μm thick) were stained with toluidine blue; thin (90 nm thick) sections were collected on open-slot collodion-coated grids, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined in a Zeiss EM900 electron microscope (ZEISS, Oberkochen, Germany) at 80 kilovolts. Sections were independently evaluated by two observers (J.J.R. and M.S.).

LC-MS and Data Analysis

Digestion of Tissue Samples

Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) was performed on 10 snap-frozen tumors previously collected by the New York University Brain Tissue Repository. Tissue samples were lysed by sonication in a solution containing 9 mol/L urea, 20 mmol/L Tris, pH 8, 0.2 mmol/L EDTA, and protease inhibitors (Complete tablet; Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Proteins were then reduced with dithiothreitol and alkylated with iodoacetamide before overnight digestion with trypsin at 37°C. The tryptic peptides were desalted using StageTips (Thermo Fischer Scientific, West Palm Beach, FL) and dried.

LC-MS

Each biological replicate was analyzed three times by LC–MS, using a Thermo Scientific EASY-nLC 1000 coupled to a Q Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). A self-packed 75-μm × 25-cm reversed-phase column (Reprosil C18; 3 μm; Dr. Maisch HPLC GmbH, Ammerbuch, Germany) was used for peptide separation. Peptides were eluted by a gradient of 3% to 30% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid over 180 minutes at a flow rate of 250 nL/minute at 45°C. The Q Exactive was operated in data-dependent mode with survey scans acquired at a resolution of 50,000 at m/z 400 (transient time, 256 milliseconds). Up to the top 10 most abundant precursors from the survey scan were selected with an isolation window of 1.6 Thomsons and fragmented by higher-energy collisional dissociation with normalized collision energies of 27. The maximum ion injection times for the survey scan and the MS/MS scans were 20 and 60 milliseconds, respectively, and the ion target value for both scan modes was set to 1,000,000.

Protein Identification

The raw files were processed using the MaxQuant computational proteomics platform version 1.2.7.0 (Max Planck Institute, Munich, Germany) for protein identification. The fragmentation spectra were used to search the UniProt human protein database (downloaded February 8, 2013) containing 87,647 protein sequences and allowing up to two missed tryptic cleavages. Carbamidomethylation of cysteine was set as a fixed modification, and oxidation of methionine and protein N-terminal acetylation were used as variable modifications for database searching. The precursor and fragment mass tolerances were set to 7 and 20 ppm, respectively. Both peptide and protein identifications were filtered at 1% false discovery rate based on decoy search using a database with the protein sequences reversed.

Proteomics Data Analysis

For each condition, there were three to four biological replicates and three technical replicates. The R package limma (www.bioconductor.org) was used to perform the following analysis. Raw spectral counts were normalized by the total number of counts per sample and then log2 transformed. Precision weights were calculated for each observation using the voom algorithm, and technical replicates were blocked. A linear model was fit to the data that took into account the interreplicate correlation, the precision weights, and the replicate blocking. limma uses the empirical Bayes method of readjusting the residual variances to increase statistical power for all parallel t-tests. Statistical significance is presented as a q value (ie, a P value that has been adjusted for multiple hypothesis testing). All genes with all positive fold changes and a q value of <0.05 were considered. limma is an open-source software package originally developed for microarray analysis and then later modified to handle RNA-sequencing counts data. It has been shown that the analogous nature of RNA-sequencing counts data and proteomics spectral counts data means that proteomics data sets can take advantage of the statistical tools developed for RNA-sequencing counts data.10

Bioinformatics Data Mining for Protein-Protein Interactions

Four databases were used to mine protein-protein interactions (PPIs): BioGRID, SPIKE, IntAct, and APID. IntAct also contains data from MINT. These databases were chosen for having purely evidence-based PPIs. REST APIs developed by PSICQUIC were queried using an in-house script (https://github.com/pambot/GEPPI, last accessed January 17, 2017) to form a network graph file (GLM format) of all PPIs between significantly regulated proteins, which was then imported into Cytoscape for visualization.

Results

Histological Subtypes of Optic Gliomas Are Indistinguishable by Imaging

To explore the role of the myxoid matrix and its contribution to optic glioma biology, we reviewed clinical and pathological data on a cohort of 120 patients with optic gliomas diagnosed at New York University Langone Medical Center from 1996 to 2014. By histology, 43 (36%) of the tumors were classified as PA (Figure 1, E and F) and 25 cases (21%) fit the WHO criteria for a PMXA (Figure 1, C and D).3 However, 52 cases (43%) could not be definitively classified as either PA or PMXA and were best classified as pilocytic astrocytoma with pilomyxoid features (PA/PMXA). PA/PMXA tumors showed various amounts of myxoid matrix present in the tumor. Furthermore, there was marked intratumoral heterogeneity, with some areas of a tumor showing morphological features of a PA and some of a PMXA. Because optic gliomas are rarely excised completely, there is a possibility of sampling bias that can influence the final histological diagnosis. Therefore, we sought to establish whether PA and PMXA can be distinguished by imaging. When comparing imaging properties of optic gliomas, for which complete comparable preoperative magnetic resonance imaging was available, we found that PA and PMXA are indistinguishable by imaging features (n = 5 per group). All optic gliomas had relatively well-defined margins and showed heterogeneous contrast enhancement, suggesting rich, but abnormally leaky, vasculature. Tumor necrosis was absent in all samples, indicating that neither hypoperfusion nor hypoxia was present (Figure 1, A and B).

Figure 1.

Imaging, histological, and immunophenotypic characteristics of optic gliomas and the microvascular network. A and B: Pilocytic astrocytoma (PA) and pilomyxoid astrocytoma (PMXA) are both well perfused and cannot be distinguished on imaging; however, they differ in the amount of the myxoid matrix and vascular density. PMXA (blue arrowhead; A) and PA (red arrowhead; B) are tumors of the optic tract. From left to right: Axial T2 and precontrast and post-contrast T1 weighted magnetic resonance images showing well-defined, T2 hyperintense, homogeneously enhancing PMXA involving the optic chiasm without any cyst formation or necrosis (A) and demonstrating well-defined PA involving the optic chiasm but with slightly heterogeneous nodular enhancement with multiple small cysts (B). C–F: Histological evaluation after hematoxylin and eosin staining shows abundant bluish myxoid matrix traversed by blood-filled channels in PMXA (arrows; C and D) but not PA (E and F). G–N: When evaluated by immunohistochemistry, channels in the myxoid matrix of PMXA (arrows) lack endothelial cells by CD34 (arrowheads, G) and Erg (arrowheads, H), markers, when compared to PA without myxoid matrix (arrowheads, I and J, respectively). However, by GLUT-1 stain, PMXA (K) and PA (M) both show good perfusion by nonendothelialized primitive myxoid vascularization channels (arrows in K) or by endothelialized blood vessels (arrowheads, M), respectively. Both tumor types lacked necrosis and were negative for hypoxia marker CA-IX (L and N), confirming equally efficient blood supply. n = 6 per group for all comparisons (G–N). Scale bar = 50 μm (C–N).

Pilocytic and Pilomyxoid Astrocytomas Show Different Microvascular Density but Similar Perfusion

To characterize the microvascular density of optic PA and PMXA on the tissue level, we performed histological and immunohistochemical analysis of six PAs and six PMXAs. We excluded all tumors that had mixed features (PA/PMXA) because of the high variability between different tissue blocks. Although our imaging analysis suggested equal blood supply and no hypoxia in both PAs and PMXAs, our histological analysis (Figure 1, C–F) and immunohistochemistry (Figure 1, G–N) demonstrated that PMXA tumors, in contrast to PAs, exhibited significantly lower microvascular density. This was defined by the presence of CD34-positive (8.1 versus 14.5 blood vessels/mm2; P < 0.002) (Figures 1, G and I, and 2A) and Erg-positive (7 versus 13.6 blood vessels/mm2; P = 0.003) (Figures 1, H and J, and 2B) endothelium-lined channels. However, when we evaluated the number of perfused blood vessels using GLUT-1, which highlights erythrocytes as well as brain endothelial cells, there was no difference in the number of perfused blood channels between PMXA and PA (15.4 versus 14.5 blood vessels/mm2) (Figures 1, K and M, and 2C). We defined a perfused blood vessel as a vascular channel filled with GLUT-1–positive erythrocytes, irrespective of the presence of the endothelium. Furthermore, PMXA and PA tumor subtypes demonstrated an absence of both necrosis on H&E staining and hypoxia by immunochemistry (Figure 1, L and N). In addition, both tumors displayed similar tumor cell proliferation rates by Ki-67 (Figure 2D). Together, these findings suggest equal functional perfusion of both tumor subtypes. Last, GLUT-1 immunohistochemistry (Figure 1K) highlighted large perfused channels within the myxoid matrix apparent on H&E staining (Figure 1, C and D). These channels maintained the shapes of blood vessels; however, they were completely devoid of endothelial cells (Figure 1, G and H). None of these channels showed histological signs of thrombus organization, fibrin thrombi, or hemosiderin deposition, suggesting that these were not recent or remote hemorrhages into a myxoid matrix. These channels were completely absent in all PAs, which in all cases showed endothelialized blood vessels (Figure 1, E and F). There are currently no patient-derived or genetically engineered murine models of PMXA, which precludes in vivo analysis of perfusion. However, in three PMXA patients, a tumor perfusion analysis was available, showing that areas of enhancement corresponded to increased blood volume, suggesting preserved perfusion in PMXA (Supplemental Figure S1), which is concordant with previous optic glioma imaging studies.11, 12

Figure 2.

Blood supply in pilomyxoid astrocytoma (PMXA) is maintained by endothelium-independent myxoid matrix (MYX). A–C: Microvascular density (presented as number of blood vessels per mm2) is markedly lower in PMXA when judged by the number of vascular channels positive for endothelial markers CD34 (A) and Erg (B); however, there is no difference when tumors are compared for the number of perfused blood vessels by GLUT-1, the marker of erythrocytes (C), suggesting equally well-perfused tumor tissue. D: In addition to the lack of hypoxia (Figure 1, L and N), the proliferation rate is similar in both groups of tumors. E–H: When PMXAs were evaluated by electron microscopy, erythrocytes (Ery) are identified within a framework of normal endothelium-lined blood vessels (red arrows; E), as well as transitional astrocyte (Ast)-lined channels (black arrows; F) and ultimately within the myxoid matrix (G and H). The red box in G is shown at higher magnification in H. Myxoid channels are devoid of endothelial lining and smooth muscle cells, whereas there is abundant fibrin (arrowheads), at the myxoid matrix-erythrocyte interface. Of note, fibrin fibers, which would suggest organizing hemorrhage, are not present in between erythrocytes. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 6 per group for all comparisons (A–D); n = 3 (E–H). ∗P < 0.005 (two-tailed t-test). Scale bars: 5 μm (E); 1 μm (F–H).

Vascular Channels in Pilomyxoid Astrocytomas Lack Endothelial Cells

Serial sectioning of PMXAs showed that erythrocytes are present in endothelialized blood vessels, which open into spaces surrounded by tumor astrocytes and finally only surrounded by the myxoid matrix (Figure 3). To confirm the absence of endothelial cells in these myxoid channels at the ultrastructural level, we performed electron microscopy and mapped the tumoral vascular network of three PMXAs for which tissue of sufficient quality was available for electron microscopy. We found that PMXAs have regular vertebrate blood vessels with endothelial lining (Figures 2E and 3) as well as channels completely lacking endothelial and smooth muscle cells (Figures 2G and 3). We observed neither myxoid channels partially lined by endothelial cells nor myxoid channels with isolated endothelial cells, confirming complete absence of endothelial cells within the myxoid matrix. Complete lack of endothelial cells by ultrastructural analysis also excludes a possibility of primitive endothelial cells or endothelial cell precursors that would lack CD34 or Erg expression. In addition, we identified a transitional zone between both types of blood channels, which was lined by glial cells in direct contact with erythrocytes (Figures 2F and 3). Channels in the myxoid matrix also lacked any ultrastructural evidence of basement membrane (Figure 2H), arguing against the secondary involution of the endothelial cell layer. The myxoid matrix contained fibrin fibers, which outlined the channel, generating a pseudomembrane in response to erythrocyte pressure on the matrix. These fibrin fibers were present only in the myxoid matrix, but not around normal blood vessels, intermediate channels, or tumor cells (Figure 2, E–G). Therefore, we concluded that fibrin in the myxoid matrix may have been extravasated from the blood because of the lack of an endothelial barrier. Fibrin extravasation from plasma into myxoid matrix may be a possible mechanism by which blood in myxoid channels does not develop fibrin microthrombi.

Figure 3.

Primitive myxoid vascularization and normal vasculature. A and B: Blood enters primitive myxoid vascularization (PMV) from a capillary (asterisk) lined by endothelium (dashed arrows) into space lacking endothelial lining but surrounded by glial (tumor) cells (red arrows). Boxed area in A is shown at higher magnification in B. See also Figure 2, E and F, for ultrastructural features. C–K: Serial sectioning shows continuity of the PMV channels and the transitional zone. Lower-power view (at level 3) showing critical elements of the pilomyxoid astrocytoma vasculature: endothelium-lined blood vessels (dashed arrow), tumor cells (red arrows), and two branches of a PMV channel (asterisks and dagger; C). Four consecutive sections (levels 1 to 4 from top to bottom) of the PMV channels; asterisks and daggers showing the connection (D and E), followed by separation of both channels (F–K). Blood is in close contact with glial tumor cells (red arrows) and nonendothelialized myxoid matrix (red arrowheads). Boxed areas in E, F, I, and J and shown at higher magnification in D, G, H, and K, respectively. No microthrombi are present. Scale bars = 50 μm (A–K).

Protein Composition of Myxoid Matrix in Optic Gliomas

When endothelial cells are not present, blood will coagulate instantly when in contact with tumor cells.13 However, myxoid matrix secreted by glioma cells does not trigger coagulation. To identify the biochemical composition of the myxoid matrix, we performed LC-MS without sample fractionation,14, 15 and for quantification, we used peptide spectral counts10 (Figure 4A). Proteomic analysis is superior to immunohistochemistry as it allows unbiased quantitative detection of peptides and proteins. We compared 10 optic glioma samples from non-neurofibromatosis type 1 patients in which sufficient frozen tumor tissue was available for analysis. Patients were sex, age, and BRAF status matched, but differed in final histological diagnosis: PA (n = 4), PMXA (n = 3), and tumors with intermediate pathological features (PA/PMXA, n = 3) (Figure 4, A and B). Clinical data are summarized in Figure 4B. The three groups of tumors differed in the amount of the myxoid matrix present on H&E staining (Figure 4C). In addition, their proteomic profiles separated them into three distinct subgroups by unsupervised analyses matching their histological classification. In total, we identified 5389 proteins, of which 188 were differentially expressed in the three groups (P < 0.05, Benjamini-Hochberg adjustment). Between PA and PMXA, we found that most of differentially expressed proteins (146/188) displayed a positive fold change (defined as increasing in PMXA relative to PA), and a minority (42/188) showed a negative fold change. The most abundant extracellular matrix protein with highest spectral count change between PA and PMXA and highest MS signal intensity and count of matched MS/MS spectra was a large chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan, versican (VCAN). VCAN is a versatile proteoglycan with numerous roles in vascular and tumor extracellular matrix biology.16, 17, 18 VCAN was identified as the most abundant protein based on total intensity and showed a 3.7-fold increase (Q = 0.000463). The versican molecular exists in at least four different isoforms generated by alternative splicing (V0, V1, V2, and V3). These isoforms differ in the size of the core protein and the number of attached chondroitin sulfate chains and cannot be reliably distinguished by LC-MS. Furthermore, these isoforms are present in different physiological and pathological states. To identify the specific VCAN isoform and confirm in the tissue sections that VCAN is produced directly by tumor cells, we performed immunohistochemistry. Immunohistochemical analysis confirmed VCAN isoform V116 is produced by glioma cells and secreted in the extracellular matrix (Figure 5). VCAN isoform V1 is expressed in brain as well as in some brain tumors. Expression of VCAN is critical for ocular development, and genetic defects in VCAN can cause autosomal dominant vitreoretinal degeneration (Wagner syndrome; Mendelian Inheritance in Man 143200) characterized by an empty vitreous cavity.19, 20, 21 VCAN interacts with link proteins [vertebrate hyaluronan and proteoglycan link protein 1 (HAPLN)] to bind hyaluronan and stabilize the extracellular matrix.16 The critical role of VCAN in eye development may be the reason why PMXA, which is characterized by massive abundance of myxoid matrix, originates almost exclusively in the optic pathway. In contrast, PA tumors can arise anywhere within the brain.

Figure 4.

Proteomic landscape of optic gliomas. A: Optic gliomas show distinct proteomic spectra that separate them into three groups: pilocytic astrocytoma (PA), pilomyxoid astrocytoma (PMXA), and intermediate PA/PMXA category. B: When comparing the top 10 relatively overexpressed and underexpressed proteins, PMXA and PA/PMXA are distinctly different from PA, including expression of versican (VCAN) and its paralog vertebrate hyaluronan and proteoglycan link protein 1 (HAPLN1). The top 10 most abundant proteins detected in optic gliomas, which are unchanged, are also shown. C and D: The amount of bluish myxoid matrix material present in optic gliomas on hematoxylin and eosin evaluation (C) strongly correlates with increased protein log-counts for VCAN and HAPLN1 obtained by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (D). With increase of these myxoid extracellular matrix proteins, there is also increase of apolipoprotein E (ApoE), which may represent a mechanism by which these channels avoid endothelial ingrowth. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (D). ∗q < 0.05, ∗∗q < 0.001, and ∗∗∗q < 0.0001. Original magnification, ×200 (C). F, female; M, male; Mut, BRAF V600E mutated; Nf1, neurofibromatosis type 1; Wt, wild type.

Figure 5.

Versican (VCAN) V1 expression in optic gliomas by immunohistochemistry. Strong expression of VCAN isoform V1 is present in pilomyxoid astrocytoma (PMXA; A and B), both in myxoid matrix (MYX; A) as well as in tumor cells (arrows), suggesting tumor cells are secreting VCAN into the extracellular space. Moderate expression is observed in pilocytic astrocytoma (PA)/PMXA (C), whereas little expression is detected in PA by immunohistochemistry (D). Scale bar = 50 μm (A–D).

The second most common protein identified was VCAN's paralog, HAPLN1 (Figure 4, B and D). HAPLN1 showed a 22-fold increase from the PA to the PMXA group (Q = 4.60 × 10−7). HAPLN1 (alias cartilage-linking protein 1) plays an important role stabilizing proteoglycan monomers with hyaluronic acid in the cartilage matrix. In contrast to brain-specific HAPLN2 and HAPLN4, HAPLN1 was not found to be expressed in the brain initially.22 However, the role of HAPLN1 is increasingly recognized as a part of the so-called perineuronal net protecting neurons.23 Furthermore, HAPLN1 is present in the eye.24 HAPLN1 and VCAN were the two most significantly positively regulated genes between PA and PMXA, according to protein spectral counts.

In addition, extracellular matrix protein 1, which is normally involved in enchondral bone formation and skin maintenance, also showed a significant 10-fold increase from the PA to the PMXA tumor group (Q = 0.000614), and inter-alpha–trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H1, which showed a fold change of 1.6 (Q = 0.00140), may play the role in carrying hyaluronan into this proteoglycan complex (Supplemental Figure S2).

In addition to PA and PMXA, our analysis included three optic gliomas with features of both PA and PMXA (PA/PMXA), clinically reported as pilocytic astrocytomas with pilomyxoid features. By proteomic spectra, these mixed tumors showed features intermediate between PA and PMXA. Based on levels of most abundant proteins, these mixed tumors appeared closer to the PMXA subgroup (Figure 4 and Supplemental Figure S2), suggesting that these tumors may clinically behave more like PMXA. Because our ultrastructural analysis identified no endothelial cells in the primitive myxoid channels, which would be expected to grow from the main endothelium-lined vascular network into the matrix, we sought to identify a potential antiangiogenic protein that could inhibit endothelial migration into the myxoid matrix of optic gliomas. For almost 40 years, vitreous has been known to display a strong inhibitory effect on neovascularization.25 Apolipoprotein E is known to be secreted into the vitreous by glial cells26 and has previously been shown to be a potent antiangiogenic factor.27 Apolipoprotein E was among the top five proteins identified by spectral counts in PMXA and showed a significant 2.7-fold increase (Q = 0.000626) from PA to PMXA tumors (Figure 4D).

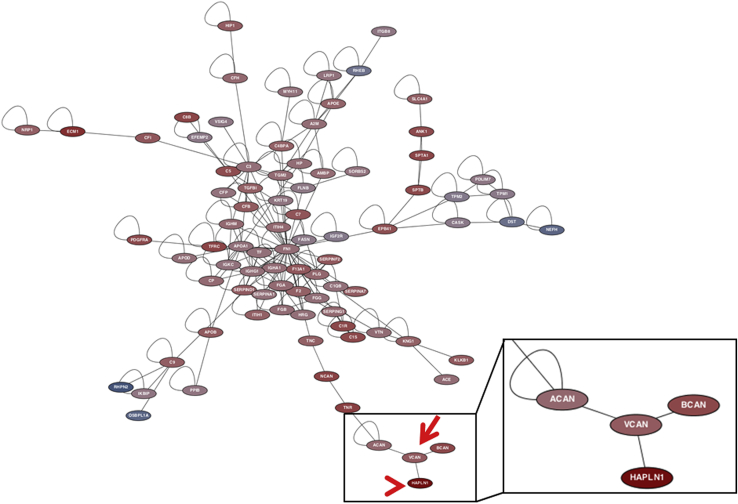

We hypothesized that the structural proteins identified by our analysis should have well-established interactions and form simple complexes. Four databases were used to assess PPIs28: BioGRID, SPIKE, APID, and IntAct, which also contains data from MINT.29, 30, 31, 32 These databases were chosen for having evidence-based PPIs. We found that the two most significant proteoglycans we identified, VCAN and HAPLN1, are part of a distinct and separate extracellular matrix regulation scheme (Figure 6), supporting our idea that the myxoid matrix structure generated by tumors is simple and composed of few components. These molecules cross-link to form a bioactive polymer that responds to biomechanical pressure of tumor tissue and circulating blood, analogous to cartilage response to mechanical pressure.33

Figure 6.

Protein-protein interactions network in optic gliomas. Protein-protein interactions database mining retrieved all experimentally derived pairs of protein interactions out of the list of differentially expressed proteins in our samples. A network graph was built with positive fold-changes [increasing in pilomyxoid astrocytoma (PMXA) relative to pilocytic astrocytoma (PA)] in red and negative (decreasing in PMXA relative to PA) fold changes in blue. Versican (VCAN; arrow) and vertebrate hyaluronan and proteoglycan link protein 1 (HAPLN1; arrowhead) have a well-established interaction and are part of a distinct branch of the proteoglycan family of proteins interacting with each other (boxed area). HAPLN1, which showed the highest increase between PA and PMXA, interacts with VCAN, which was the most abundant protein by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry.

Discussion

Herein, we show that optic gliomas can develop endothelium-independent channels reminiscent of those in invertebrates facilitated by a vitreous-like extracellular matrix. In vertebrate organisms, endothelial cells play the main role in physiological as well as pathological angiogenesis, including cancer. Neovascularization is a hallmark feature of human gliomas, and five distinct mechanisms have been described: i) vascular co-option, ii) angiogenesis, iii) vasculogenesis, iv) vascular mimicry, and last v) endothelial cell transdifferentiation.5 Our findings reveal a previously unrecognized mechanism characterized by tumors producing a glycosaminoglycan-rich extracellular matrix, which enables endothelium-free blood circulation. Prototypical pathological neovascularization in gliomas results in endothelial proliferation with tortuous and abnormally branching leaky vessels, leading to thrombosis, hypoxia, and necrosis. However, our human imaging and histology data suggest that primitive myxoid vascularization (PMV) lacks thrombosis and provides oxygen and nutrients at a level similar to endothelialized blood vessels in grade-matched astrocytic tumors. The blood exiting vascular spaces is somewhat reminiscent of a vascular mimicry, a phenomenon well documented previously in uveal melanoma and malignant glioma.34, 35 Several studies have also shown that in vascular mimicry, erythrocytes are in direct contact with tumor cells expressing anticoagulative endothelial and stem cell markers,36, 37 and that vascular mimicry channels are definitely anastomosed with the vasculature mainframe and they exhibit blood flow via imaging studies.38, 39, 40 Although our study lacks murine models that would allow conducting a similar analysis, these vascular mimicry studies provide strong evidence that nonendothelialized vascular channels in tumors can be connected to the vasculature with preserved blood flow. However, in contrast to vascular mimicry, where blood is solely in contact with tumor cells, PMV is facilitated by abundant myxoid matrix separating tumor cells from the blood. The massive amount of myxoid matrix is a characteristic feature of optic gliomas, largely responsible for the mass effect of the tumor and not present in other cancers; however, its biological function remained elusive. Our report suggests that it may play a critical role in blood supply.

Loss of endothelial cells is a strong trigger of coagulation cascade, and fibrin thrombi can be identified in tissues easily by histology or by electron microscopy. In vascular mimicry, which also lacks endothelial cells, the expression of anticoagulative factors has been clearly documented on tumor cells, allowing blood to flow freely by preventing tissue factor–mediated clotting.41 In the complete absence of endothelial cells, we observed direct contact of erythrocytes with the myxoid matrix by electron microscopy. However, we did not observe fibrin thrombi in the PMV channels, although we identified massive deposition of fibrin fibers in the myxoid matrix by electron microscopy. Because fibrin is a critical component of a blood clot, the lack of fibrin, which is absorbed by the myxoid matrix, may contribute to the lack of coagulation and preservation of the blood flow, although this will require further mechanistic evidence. Although hypercoagulation is a known paraneoplastic syndrome of many solid tumors, hypocoagulative properties of isocitrate dehydrogenase genes 1/2 mutant gliomas have recently been recognized.42

The timeline of the PMV evolution during tumor development remains unclear. PMXA contains a framework of normal blood vessels from which nonendothelialized channels branch out with short intermediate segments lined by tumor astrocytes. It is possible that PMV channels were originally lined by endothelial cells, which then regressed during tumor growth. Although we cannot exclude that loss of endothelium occurred after development of PMV channels, we did not observe any evidence of a basement membrane or partially lined channels that would suggest the presence of a preexisting or involuting endothelial layer. The lack of patient-derived orthotopic or genetically engineered mouse models of PMXA currently precludes mechanistic studies of optic glioma angiogenesis.

We identified VCAN as the major structural component of the myxoid matrix in optic gliomas. VCAN is a proteoglycan that belongs to the family of large aggregating chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans, hyalectins. The hyalectin family also includes aggrecan, present in cartilage; brevican and neurocan, which are prominent in the nervous system; and versican, which is mostly present in the soft tissues. VCAN has been shown to play a central role in extracellular matrix, such as elastic fiber assembly interacting with fibrilin and fibulin.16 The entanglement of absorbed fibrin observed in our study may represent a similar mechanism to maintain elasticity of the myxoid matrix in response to the blood pressure. The revealed complexity of optic glioma microenvironment and potential dependence on the myxoid matrix in addition to a combination of endothelialized and nonendothelialized blood vessels may be the reason why optic glioma cells do not grow well in vitro, precluding detailed cell culture studies. The development of murine models of optic glioma has also been challenging despite their well-understood genetics. There are currently no murine models of pilomyxoid astrocytoma or non-Nf1 models of optic glioma. One potential explanation is that the murine optic system microenvironment does not reflect that of humans or that different proteins are expressed during murine optic tract development.

Grading of pilomyxoid astrocytoma has recently been changed from WHO grade II with the recommendation not to assign the WHO grade, citing the insufficient evidence to establish prognostic significance of the pilomyxoid histology for poor outcome. This is in part because of relatively loose diagnostic criteria of pilomyxoid astrocytoma, resulting in a large number of tumors showing intermediate features. Our data indicate that tumors with mixed PA/PMXA features appear, at least on the proteomic level, closer to PMXA than to PA regardless of the underlying genetics. In future studies, pilomyxoid diagnosis may be better defined by the presence of VCAN than histological features alone.

Our findings are focused on optic gliomas, but myxoid matrix has long been observed in a variety of human cancers by pathologists.43 To explore whether similar structures are found in other tumors with abundant myxoid matrix, we reviewed histological sections of archival cases of clear cell carcinoma of the kidney, chordoid meningioma, well-differentiated chondrosarcoma, and chordoma. Histological analysis of these other tumor types exhibited similar channels lacking endothelial lining (Figure 7), suggesting that the primitive myxoid vascularization is not unique to optic pathway gliomas, but may represent a more common, previously unappreciated, biological phenomenon of the tumor microvasculature in cancer. However, further studies are necessary to identify structural proteins of the myxoid matrix in these non–central nervous system tumors.

Figure 7.

Primitive myxoid vascularization (PMV) in other tumors. In addition to optic gliomas, we observed PMV (arrows) in other tumors with abundant myxoid matrix, such as renal clear cell carcinoma (A), meningioma (B), chordoma (C), and chondrosarcoma (D), suggesting that endothelium-independent vascularization may be present in other neoplasms throughout the body and may represent more common biological phenomena. Scale bar = 50 μm (A–D).

Why tumors may develop endothelium-free channels during their growth remains unclear. One possible explanation as to why tumor cells revert to an evolutionary primitive mechanism is that this mechanism of blood supply allows the tumor to maintain blood supply by fewer endothelial cells in the tumor mass. With endothelial cells limited mostly to the larger vascular branches and diffusion of oxygen and nutrients from circulating blood through the acellular myxoid matrix directly to tumor cells, the primitive myxoid vascularization may provide cancer cells with a competitive advantage in access to nutrients and oxygen. Future animal studies are necessary to provide direct evidence of blood flow in PMV and to elucidate the mechanism of PMV development and biological function.

Last, our findings present a potential therapeutic avenue in optic gliomas by targeting the extracellular matrix. The myxoid matrix is in direct contact with blood with no intervening endothelium blood-brain barrier and is therefore readily accessible to blood circulating therapeutics. Targeting the PMV matrix with VCAN/HAPLN1 cleaving enzymes may provide novel avenues for therapy of optic gliomas. Directly targeting these matrix proteins has the potential to both decrease the tumor mass and its pressure on the brain/optic tract and enable chemotherapy and targeted agents to better reach tumor cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sarah Chiang for review and helpful suggestions and Martin Sellig for blinded review of electron microscopy images.

Footnotes

Supported by a grant from The Making Headway Foundation (to New York University), NIH grants P30 NS050276 and S10 RR027990 (T.A.N.), The Friedberg Charitable Foundation grant (M.S.), and NIH/National Cancer Institute grant R21NS074055 (D.Z.). The New York University Langone Human Specimen Resource Center, Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center, and Clinical and Translational Science Institute are supported in part by the Cancer Center Support grant P30CA016087 and the National Center for the Advancement of Translational Science, NIH grant UL 1 TR000038.

Disclosures: None declared.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2017.04.004.

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Figure S1.

Thirteen-year-old female with pilomyxoid astrocytoma of the optic chiasm. Post-contrast T1 weighted magnetic resonance (MR) image (A) showing areas of enhancement in the central part of the tumor with corresponding increased blood volume (arrow; B) [relative cerebral blood volume (rCBV) = 3.5 to 4.0] relative to the normal-appearing white matter, suggesting hyperperfusion on DSC T2* MR perfusion image. Hemorrhage or necrosis is not identified.

Supplemental Figure S2.

The top five proteins with increased spectral counts from pilocytic astrocytoma (PA) to pilomyxoid astrocytoma (PMXA) include versican (VCAN), vertebrate hyaluronan and proteoglycan link protein 1 (HAPLN1), apolipoprotein E (APOE), extracellular matrix protein 1 (ECM1), and inter-alpha–trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H1 (ITIH1). VCAN is the most abundant protein in the pilomyxoid astrocytomas; however, HAPLN1 shows the highest increase from PA to PMXA, suggesting the importance of the linking protein to assemble and maintain the myxoid matrix in optic gliomas. ITIH1 plays a critical role in bringing hyaluronic acid into the proteoglycan complex.

References

- 1.Rodriguez F.J., Ligon A.H., Horkayne-Szakaly I., Rushing E.J., Ligon K.L., Vena N., Garcia D.I., Cameron J.D., Eberhart C.G. BRAF duplications and MAPK pathway activation are frequent in gliomas of the optic nerve proper. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2012;71:789–794. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3182656ef8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodriguez F.J., Lim K.S., Bowers D., Eberhart C.G. Pathological and molecular advances in pediatric low-grade astrocytoma. Annu Rev Pathol. 2013;8:361–379. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020712-164009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Louis D.N., Ohgaki H., Wiestler O.D., Cavenee W.K., Ellison D.W., Figarella-Branger D., Perry A., Reifenberger G., von Deimling A. IARC Press; Lyon: 2016. WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munoz-Chapuli R. Evolution of angiogenesis. Int J Dev Biol. 2011;55:345–351. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.103212rm. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hardee M.E., Zagzag D. Mechanisms of glioma-associated neovascularization. Am J Pathol. 2012;181:1126–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carmeliet P., Jain R.K. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature. 2011;473:298–307. doi: 10.1038/nature10144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Munoz-Chapuli R., Carmona R., Guadix J.A., Macias D., Perez-Pomares J.M. The origin of the endothelial cells: an evo-devo approach for the invertebrate/vertebrate transition of the circulatory system. Evol Dev. 2005;7:351–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2005.05040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shigei T., Tsuru H., Ishikawa N., Yoshioka K. Absence of endothelium in invertebrate blood vessels: significance of endothelium and sympathetic nerve/medial smooth muscle in the vertebrate vascular system. Jpn J Pharmacol. 2001;87:253–260. doi: 10.1254/jjp.87.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.di Tomaso E., Snuderl M., Kamoun W.S., Duda D.G., Auluck P.K., Fazlollahi L., Andronesi O.C., Frosch M.P., Wen P.Y., Plotkin S.R., Hedley-Whyte E.T., Sorensen A.G., Batchelor T.T., Jain R.K. Glioblastoma recurrence after cediranib therapy in patients: lack of “rebound” revascularization as mode of escape. Cancer Res. 2011;71:19–28. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anders S., McCarthy D.J., Chen Y., Okoniewski M., Smyth G.K., Huber W., Robinson M.D. Count-based differential expression analysis of RNA sequencing data using R and Bioconductor. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:1765–1786. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vinhais S. Optic gliomas in children: a review on MR imaging findings. European Congress of Radiology. 2015 Poster ECR 2015/C-1676. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lémery-Magnin M. Perfusion weighted imaging in pediatric low grade glioma. European Congress of Radiology. 2015 Poster ECR2014/C-1270. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shoji M., Hancock W.W., Abe K., Micko C., Casper K.A., Baine R.M., Wilcox J.N., Danave I., Dillehay D.L., Matthews E., Contrino J., Morrissey J.H., Gordon S., Edgington T.S., Kudryk B., Kreutzer D.L., Rickles F.R. Activation of coagulation and angiogenesis in cancer: immunohistochemical localization in situ of clotting proteins and vascular endothelial growth factor in human cancer. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:399–411. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michalski A., Damoc E., Hauschild J.P., Lange O., Wieghaus A., Makarov A., Nagaraj N., Cox J., Mann M., Horning S. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics using Q Exactive, a high-performance benchtop quadrupole Orbitrap mass spectrometer. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10 doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.011015. M111.011015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cox J., Mann M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1367–1372. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wight T.N., Kinsella M.G., Evanko S.P., Potter-Perigo S., Merrilees M.J. Versican and the regulation of cell phenotype in disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1840:2441–2451. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu Y.J., La Pierre D.P., Wu J., Yee A.J., Yang B.B. The interaction of versican with its binding partners. Cell Res. 2005;15:483–494. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheng W., Wang G., Wang Y., Liang J., Wen J., Zheng P.S., Wu Y., Lee V., Slingerland J., Dumont D., Yang B.B. The roles of versican V1 and V2 isoforms in cell proliferation and apoptosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:1330–1340. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-04-0295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kloeckener-Gruissem B., Bartholdi D., Abdou M.T., Zimmermann D.R., Berger W. Identification of the genetic defect in the original Wagner syndrome family. Mol Vis. 2006;12:350–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyamoto T., Inoue H., Sakamoto Y., Kudo E., Naito T., Mikawa T., Mikawa Y., Isashiki Y., Osabe D., Shinohara S., Shiota H., Itakura M. Identification of a novel splice site mutation of the CSPG2 gene in a Japanese family with Wagner syndrome. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2726–2735. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mukhopadhyay A., Nikopoulos K., Maugeri A., de Brouwer A.P., van Nouhuys C.E., Boon C.J., Perveen R., Zegers H.A., Wittebol-Post D., van den Biesen P.R., van der Velde-Visser S.D., Brunner H.G., Black G.C., Hoyng C.B., Cremers F.P. Erosive vitreoretinopathy and wagner disease are caused by intronic mutations in CSPG2/Versican that result in an imbalance of splice variants. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:3565–3572. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spicer A.P., Joo A., Bowling R.A., Jr. A hyaluronan binding link protein gene family whose members are physically linked adjacent to chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan core protein genes: the missing links. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:21083–21091. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213100200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suttkus A., Rohn S., Weigel S., Glockner P., Arendt T., Morawski M. Aggrecan, link protein and tenascin-R are essential components of the perineuronal net to protect neurons against iron-induced oxidative stress. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1119. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishikawa M., Sawada Y., Yoshitomi T. Structure and function of the interphotoreceptor matrix surrounding retinal photoreceptor cells. Exp Eye Res. 2015;133:3–18. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Preis I., Langer R., Brem H., Folkman J. Inhibition of neovascularization by an extract derived from vitreous. Am J Ophthalmol. 1977;84:323–328. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(77)90672-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amaratunga A., Abraham C.R., Edwards R.B., Sandell J.H., Schreiber B.M., Fine R.E. Apolipoprotein E is synthesized in the retina by Muller glial cells, secreted into the vitreous, and rapidly transported into the optic nerve by retinal ganglion cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5628–5632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pencheva N., Tran H., Buss C., Huh D., Drobnjak M., Busam K., Tavazoie S.F. Convergent multi-miRNA targeting of ApoE drives LRP1/LRP8-dependent melanoma metastasis and angiogenesis. Cell. 2012;151:1068–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aranda B., Blankenburg H., Kerrien S., Brinkman F.S., Ceol A., Chautard E. PSICQUIC and PSISCORE: accessing and scoring molecular interactions. Nat Methods. 2011;8:528–529. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chatr-Aryamontri A., Breitkreutz B.J., Heinicke S., Boucher L., Winter A., Stark C., Nixon J., Ramage L., Kolas N., O'Donnell L., Reguly T., Breitkreutz A., Sellam A., Chen D., Chang C., Rust J., Livstone M., Oughtred R., Dolinski K., Tyers M. The BioGRID interaction database: 2013 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D816–D823. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hermjakob H., Montecchi-Palazzi L., Lewington C., Mudali S., Kerrien S., Orchard S., Vingron M., Roechert B., Roepstorff P., Valencia A., Margalit H., Armstrong J., Bairoch A., Cesareni G., Sherman D., Apweiler R. IntAct: an open source molecular interaction database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D452–D455. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paz A., Brownstein Z., Ber Y., Bialik S., David E., Sagir D., Ulitsky I., Elkon R., Kimchi A., Avraham K.B., Shiloh Y., Shamir R. SPIKE: a database of highly curated human signaling pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D793–D799. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prieto C., De Las Rivas J. APID: Agile Protein Interaction DataAnalyzer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W298–W302. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Responte D.J., Lee J.K., Hu J.C., Athanasiou K.A. Biomechanics-driven chondrogenesis: from embryo to adult. FASEB J. 2012;26:3614–3624. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-207241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hendrix M.J., Seftor E.A., Hess A.R., Seftor R.E. Vasculogenic mimicry and tumour-cell plasticity: lessons from melanoma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:411–421. doi: 10.1038/nrc1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El Hallani S., Boisselier B., Peglion F., Rousseau A., Colin C., Idbaih A., Marie Y., Mokhtari K., Thomas J.L., Eichmann A., Delattre J.Y., Maniotis A.J., Sanson M. A new alternative mechanism in glioblastoma vascularization: tubular vasculogenic mimicry. Brain. 2010;133:973–982. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dunleavey J.M., Dudley A.C. Vascular mimicry: concepts and implications for anti-angiogenic therapy. Curr Angiogenes. 2012;1:133–138. doi: 10.2174/2211552811201020133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spiliopoulos K., Peschos D., Batistatou A., Ntountas I., Agnantis N., Kitsos G. Vasculogenic mimicry: lessons from melanocytic tumors. In Vivo. 2015;29:309–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clarijs R., Otte-Holler I., Ruiter D.J., de Waal R.M. Presence of a fluid-conducting meshwork in xenografted cutaneous and primary human uveal melanoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:912–918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kobayashi H., Shirakawa K., Kawamoto S., Saga T., Sato N., Hiraga A., Watanabe I., Heike Y., Togashi K., Konishi J., Brechbiel M.W., Wakasugi H. Rapid accumulation and internalization of radiolabeled herceptin in an inflammatory breast cancer xenograft with vasculogenic mimicry predicted by the contrast-enhanced dynamic MRI with the macromolecular contrast agent G6-(1B4M-Gd)(256) Cancer Res. 2002;62:860–866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frenkel S., Barzel I., Levy J., Lin A.Y., Bartsch D.U., Majumdar D., Folberg R., Pe'er J. Demonstrating circulation in vasculogenic mimicry patterns of uveal melanoma by confocal indocyanine green angiography. Eye (Lond) 2008;22:948–952. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ruf W., Seftor E.A., Petrovan R.J., Weiss R.M., Gruman L.M., Margaryan N.V., Seftor R.E., Miyagi Y., Hendrix M.J. Differential role of tissue factor pathway inhibitors 1 and 2 in melanoma vasculogenic mimicry. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5381–5389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Unruh D., Schwarze S.R., Khoury L., Thomas C., Wu M., Chen L., Chen R., Liu Y., Schwartz M.A., Amidei C., Kumthekar P., Benjamin C.G., Song K., Dawson C., Rispoli J.M., Fatterpekar G., Golfinos J.G., Kondziolka D., Karajannis M., Pacione D., Zagzag D., McIntyre T., Snuderl M., Horbinski C. Mutant IDH1 and thrombosis in gliomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;132:917–930. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1620-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Willems S.M., Wiweger M., van Roggen J.F., Hogendoorn P.C. Running GAGs: myxoid matrix in tumor pathology revisited: what's in it for the pathologist? Virchows Arch. 2010;456:181–192. doi: 10.1007/s00428-009-0822-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]