Abstract

A convergent synthesis of the complex, doubly-branched pentasaccharide domain of the natural-product immunoadjuvant jujuboside A is described. The key step is a sterically-hindered glycosylation reaction between a branched trisaccharide trichloroacetimidate glycosyl donor and a disaccharide glycosyl acceptor. Conventional Lewis acids (TMSOTf, BF3·Et2O) were ineffective in this glycosylation, but B(C6F5)3 catalyzed the reaction successfully. Inherent complete diastereoselectivity for the undesired α-anomer was overcome by rational optimization with a nitrile solvent system (1:5 t-BuCN/CF3Ph) to provide flexible, effective access to the β-linked pentasaccharide.

Graphical Abstract

Immunoadjuvants are critical components of modern molecular vaccines that enhance or prolong the immune response to antigens with which they are coadministered.1 Several saponin natural products exhibit immunoadjuvant activity and the most frequently used are derived from the Quillaja saponaria tree.2 Purified fraction QS-21, which is a mixture of two isomeric saponins QS-21-Api and QS-21-Xyl,3 is particularly active and widely used. It has been investigated extensively in clinical vaccine development4 and is a component of the Mosquirix malaria vaccine.5 Although Quillaja saponaria extracts have been shown to be effective in various vaccine formulations, they have several drawbacks including dose-limiting toxicity and chemical instability.4e Thus, the development of new adjuvants with lower toxicity and higher chemical stability is of great therapeutic interest.6

Jujuboside A (1, Figure 1) is a promising natural product immunoadjuvant in this regard. Initial work by Yoshikawa demonstrated that, in mice immunized with ovalbumin, coadministration of jujuboside A increased antibody responses by >4-fold compared to no-adjuvant controls, approaching the increase observed with QS-21 (6.7-fold).7 In a subsequent study comparing the adjuvant and hemolytic activities of 47 saponins, jujuboside A showed higher adjuvant activity and much lower hemolytic activity than QS-21.8 This combination makes jujuboside A a promising adjuvant for further preclinical investigation. Thus, as a part of our long-standing program on saponin immunoadjuvants,6, 9 we launched synthetic efforts toward the first chemical synthesis of jujuboside A, which would then enable systematic structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies. Noting that the carbohydrate domain often plays a key role in saponin immunoadjuvant activity, we first sought to develop an efficient, flexible route to the complex, doubly-branched pentasaccharide of jujuboside A. Herein, we report the rapid, convergent synthesis of this pentasaccharide, leveraging B(C6F5)3-catalyzed Schmidt glycosylation to join hindered trisaccharide and disaccharide subunits.

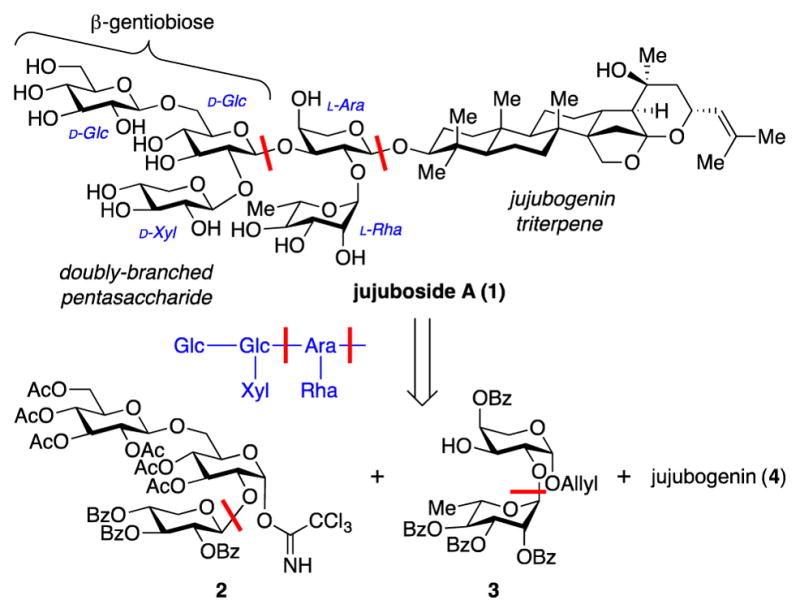

Figure 1.

Structure and retrosynthesis of the saponin immunoadjuvant jujuboside A (1).

Saponins often contain an oligosaccharide that is branched at a C2 position.10 Conventional synthetic approaches to such branched oligosaccharides use a temporary protecting group at C2 to facilitate the glycosylation reaction and control the stereochemistry of the newly formed glycosidic bond through neighboring group participation.11 This protecting group must then be removed to allow installation of the C2 branching saccharide. Although this strategy provides effective control of anomeric stereochemistry, it requires a linear synthesis. In contrast, direct coupling of glycan donors with a branching saccharide already installed at C2 would allow a more efficient and flexible convergent synthesis and facilitate SAR studies.

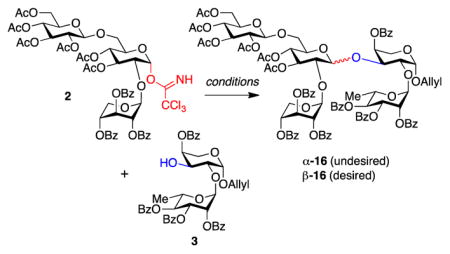

Our plan for assembly of the branched pentasaccharide domain of jujuboside (1) involved convergent coupling of a Glc-Glc-Xyl trisaccharide glycosyl donor 2 and Ara-Rha disaccharide glycosyl acceptor 3. The β-linked-diglucose fragment corresponds to commercially available β-gentiobiose. Thus, the trisaccharide and disaccharide subunits could each be assembled using a single glycosylation reaction. Although this strategy is highly convergent, the key trisaccharide–disaccharide coupling posed several challenges: 1) Both the trisaccharide donor 3 and disaccharide acceptor 2 are highly-substituted and sterically-hindered due to the C2 carbohydrate appendages. 2) Due to this same C2 carbohydrate appendage in glycosyl donor 3, the reaction would not benefit from neighboring group participation and, thus, obtaining the desired β-linkage could be challenging as coupling of hindered subunits is known to suffer from low yields and low β-selectivity, even with a C2 neighboring group.12 3) The glycosyl donor 3 has a C3-acetate, and electron-withdrawing substituents at this position are known to favor formation of α linkages.13

We noted that every glycosidic linkage in the jujuboside A pentasaccharide has a 1,2-trans configuration and, therefore, traditional neighboring group participation effects using ester protecting groups could be leveraged in the synthesis of the trisaccharide and disaccharide subunits.14 Thus, we focused on acetyl and benzoyl protecting groups to enable global deprotection at the completion of the synthesis. In addition to their efficiency in controlling the desired 1,2-trans relative stereochemistry, we envisioned that removal of these protecting groups under basic conditions would be orthogonal to the other functional groups present in the natural product.

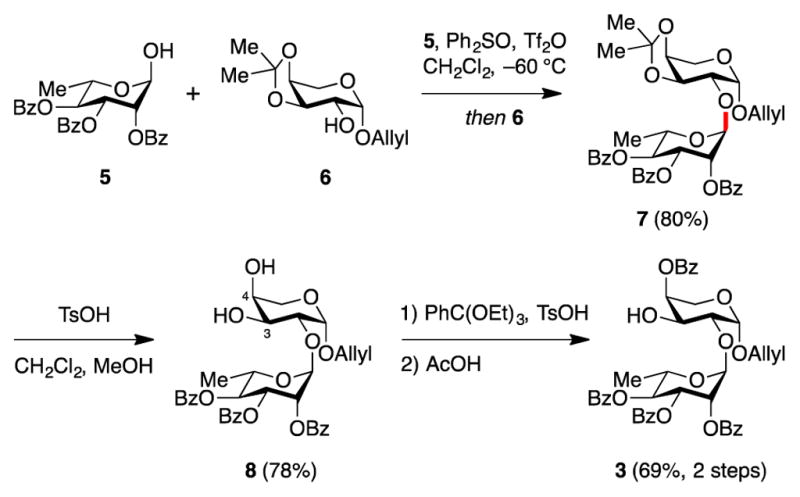

Access to the Ara-Rha disaccharide 3 was achieved using the dehydrative glycosylation method developed previously by our group.15 The hemiacetal of protected rhamnose 5 was activated with diphenylsulfoxide/triflic anhydride and reacted with glycosyl acceptor 6, both prepared as previously described,16 to deliver disaccharide 7 (Scheme 1). Removal of the acetonide protecting group under acidic conditions gave diol 8. Selective reprotection of the C4-hydroxyl of the arabinopyranose through formation of a mixed orthoester followed by selective hydrolysis17 provided protected disaccharide 3 with the arabinose C3-hydroxyl group available for use in the key convergent glycosylation reaction below.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of glycosyl acceptor disaccharide 3.

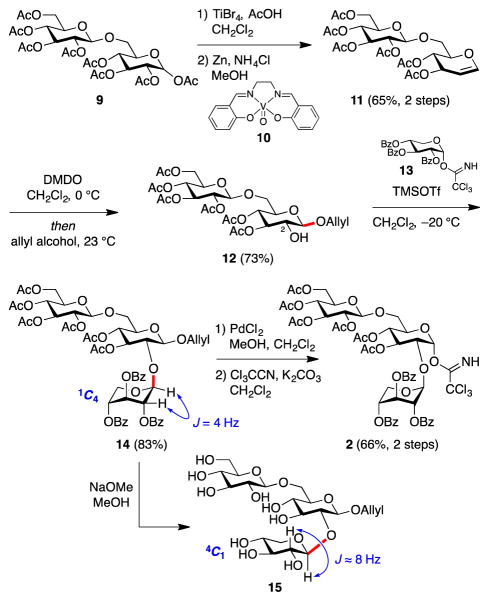

Assembly of Glc-Glc-Xyl trisaccharide subunit 2 began with preparation of glycal 11 (Scheme 2). Two procedures for conversion of β-gentiobiose octaacetate (9) to glycosylglucal 11 have been reported.18 In the first approach, AcOH/HBr is used to prepare the corresponding glycosyl bromide, which then undergoes elimination reaction to form the corresponding glucal.18a However, in our hands, this procedure gave the disaccharide glycosyl bromide intermediate in low yield and purity. In the second approach, treatment of β-gentiobiose octaacetate (9) with TiBr4 gave the desired glycosyl bromide intermediate in high purity and yield.18b However, subsequent elimination using Zn/Cu18b gave inconsistent results. As an alternative, we found that vanadium catalyst 10 combined with zinc as a stoichiometric reducing agent effected elimination to glucosylglucal 11 in good overall yield.19 Next, epoxidation of glycal 11 with DMDO20 followed by epoxide opening with allyl alcohol, furnished the disaccharide 12 with a free C2-hydroxyl group for further extension. Coupling of disaccharide 12 with trichloroacetimidate 13, prepared as previously described,21 gave trisaccharide 14 as a single anomer.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of glycosyl donor trisaccharide 2.

Detailed structural assignment using extensive NMR studies identified all three anomeric protons in trisaccharide 14, with H1–H2 coupling constants of 7.95, 7.69, and 4.00 Hz. The last coupling constant was too small for a typical β-linked glycosydic bond. However, xylose can exist in an alternative 1C4-conformation (via chair flip), which could explain this small coupling constant. This alternative conformation often results with ester protecting groups.22 Thus, to determine the stereochemistry of newly formed glycosidic bond unambiguously, we removed all acetate and benzoate protecting groups in trisaccharide 14 with NaOMe/MeOH. Analysis of the crude reaction product 15 using 1H- and 2D-NMR confirmed that all glycosidic linkages were, indeed, in the β-configuration (J = 8.01, 7.90, 7.77 Hz). Subsequently, deallylation of trisaccharide 14 using PdCl2,17 followed by trichloroacetimidate formation delivered trisaccharide donor 2.

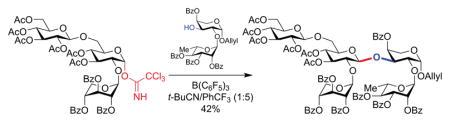

With disaccharide 3 and trisaccharide trichloroacetimidate 2 in hand, the stage was set for the key convergent coupling to form doubly-branched pentasaccharide 16 (Table 1). TMSOTf is often used as a Lewis acid in Schmidt glycosylations,23 but resulted only in decomposition of trichloroacetimidate 2 (entry 1). Another commonly used Lewis acid, BF3·OEt2,23 gave only trace amounts of the undesired α-anomer of pentasaccharide 16. In our group’s previous synthesis of the immunoadjuvant QS-21, we found that B(C6F5)3 was superior to BF3·OEt2 for sterically-hindered glycosylations.9b Indeed, with this catalyst, coupling of trisaccharide 2 and disaccharide 3 proceeded in good yield, albeit providing the undesired α-linked pentasaccharide α-16 as the sole product (entry 3).

Table 1.

Optimization of convergent glycosylation reaction to form pentasaccharide 16.a

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | reagent | solvent | temp (°C) | β: α | Yieldb (%) |

| 1 | TMSOTf | CH2Cl2 | −20 | – | 0c,d |

| 2 | BF3·OEt2 | CH2Cl2 | −20 | 0:1 | 7 |

| 3 | B(C6F5)3 | CH2Cl2 | 23 | 0:1 | 52 |

| 4 | HB(C6F5)4 | CH2Cl2 | −78 | – | 0c |

| 5 | HB(C6F5)4 | t-BuCN/CF3Phe | −78 | – | 0c |

| 6 | B(C6F5)3 | t-BuCN/CF3Phe | 23 | 1.2:1 | 81f |

| 7 | B(C6F5)3 | t-BuCN/CF3Phe | 0 | 1:1.2 | 25 |

Reactions were carried out with 0.01 mmol of trichloroimidate 2, 0.012 mmol of disaccharide 3 and 0.1 equiv of the activator reagent.

Combined yield for α-16 and β-16.

Decomposition of trichloroacetimidate 2 observed.

This reaction was also attempted at −78 °C, at 0 °C, and with the addition of 4 Å molecular sieves, leading in all cases to decomposition of tricholoroimidate 2.

1:5 ratio of t-BuCN/CF3Ph.

Desired anomer β-16 isolated in 42% yield.

The presence of an ester protecting group at the C3 position of hexose carbohydrate donors is known to favor formation of α-glycosides.13 Thus, the α-selectivity of our key glycosylation reaction is consistent with the presence of a C3-acetate in trisaccharide donor 2. However, Mukaiyama has reported that solvent and counteranion also have dramatic effects on the stereochemical outcome of glycosylations.24 In particular, combination of a t-BuCN/CF3Ph (1:5) solvent system and HB(C6F5)4 catalyst favored formation of β-glycosides. Unfortunately, use of HB(C6F5)4 in our key glycosylation reaction, resulted only in decomposition of trichloroacetimidate 2, in both CH2Cl2 and t-BuCN/CF3Ph (entries 4, 5).

Building upon our finding that reaction with B(C6F5)3 gave pentasaccharide α-16 in good yield but undesired α-selectivity (entry 3), we noted that nitrile-containing solvents are known to favor 1,2-trans β-selectivity in glycosylation reactions.25 The nitrile solvent is proposed to occupy the α-face of the oxocarbenium intermediate due to the anomeric effect, resulting in addition of nucleophiles from β-face. Accordingly, after some optimization, we discovered that the combination of B(C6F5)3 catalyst and t-BuCN/CF3Ph solvent system afforded pentasaccharide 16 in 81% combined yield and 1.2:1 α/β selectivity, overcoming the inherent complete stereopreference for the undesired α-anomer (entry 6). The desired β-anomer β-16 could then be isolated in serviceable 42% yield. Decreasing the temperature resulted in a slight erosion of β-selectivity and a significant decrease in yield (entry 7).

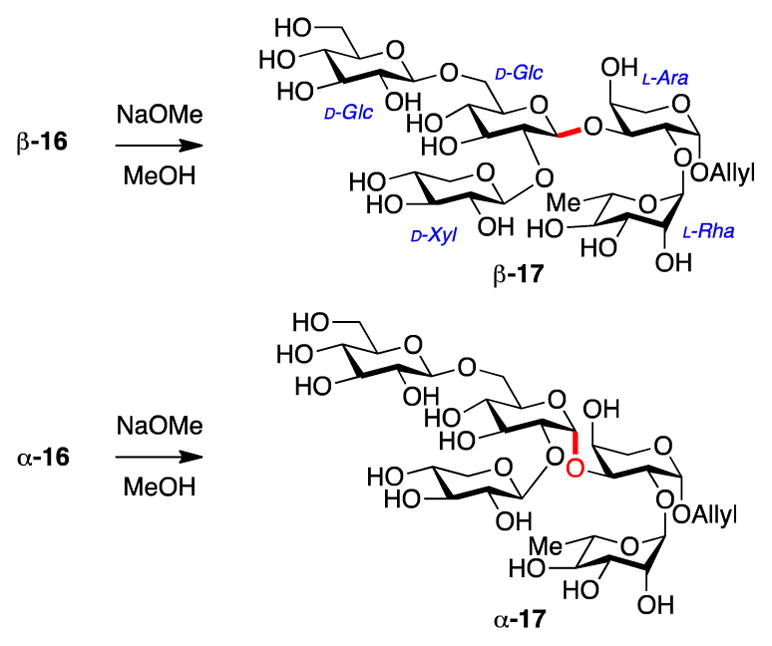

Stereochemical assignment of the newly formed glycosidic bond was accomplished by a similar strategy to that used above for trisaccharide 14. Thus, global deprotection of ester protecting groups in β-16 and α-16 gave pentasaccharides β-17 and α-17, respectively (Scheme 3). 1H-NMR and HSQC analysis of pentasaccharide β-17 identified three anomeric protons with large coupling constants (7.97, 7.81, 8.06 Hz), corresponding to the three β-linked glycosyl bonds. Two additional anomeric protons with small coupling constants (3.68, 1.69 Hz) were assigned to the α-linked arabinose and rhamnose anomeric protons. In contrast, pentasaccharide α-17 had only two anomeric protons with large coupling constants (7.94, 7.75 Hz), corresponding to β-linked terminal glucose and xylose anomeric centers. Three other anomeric protons with small coupling constants (3.69, 1.69, 0.96 Hz) were observed, consistent with an α-linkage at the newly formed glycosidic bond, in addition to the α-linked arabinose and rhamnose residues.

Scheme 3.

Global deprotection of pentasaccharides β-16 and α-16 for stereochemical assignment of newly-formed glycosidic bond.

In conclusion, we have successfully synthesized the complex, doubly-branched pentasaccharide domain of the immuno-adjuvant jujuboside A (1). Our highly convergent synthetic route gave pentasaccharide β-16 in a longest linear sequence of 7 steps and 11% overall yield (73% per step average). The trisaccharide (2) and disaccharide (3) subunits were constructed rapidly and late-stage convergent coupling using B(C6F5)3-catalyzed glycosylation in an optimized t-BuCN/CF3Ph nitrile solvent system overcame the steric hindrance and lack of neighboring group participation in the substrate system, providing effective access to the desired β-anomer. This sets the stage for synthesis of the triterpenoid core and coupling to this pentasaccharide to complete the natural product. Although the stereoselectivity of the key glycosylation step is modest, the highly convergent nature of this synthetic strategy is attractive for rapid generation of oligosaccharide analogues of jujuboside A for SAR studies in the future.

We thank Prof. Samuel Danishefsky and Dr. William Walkowicz for helpful discussions and Dr. G. Sukenick, Dr. H. Liu, H. Fang, and Dr. S. Rusli (MSKCC) for expert mass spectral analyses. Financial support from the NIH (R01 GM058833 to D.S.T. and D.Y.G. and P30 CA008748 to C. B. Thompson) is gratefully acknowledged.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Experimental procedures and analytical data for all new compounds. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Notes and references

- 1.McCluskie MJ, Weeratna RD. Curr Drug Targets Infect Disord. 2001;1:263–271. doi: 10.2174/1568005014605991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kensil CR, Patel U, Lennick M, Marciani D. J Immunol. 1991;146:431–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soltysik S, Bedore DA, Kensil CR. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;690:392–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb44041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Kennedy JS, Co M, Green S, Longtine K, Longtine J, O’Neill MA, Adams JP, Rothman AL, Yu Q, Johnson-Leva R, Pal R, Wang S, Lu S, Markham P. Vaccine. 2008;26:4420–4424. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.05.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Vandepapeliere P, Horsmans Y, Moris P, Van Mechelen M, Janssens M, Koutsoukos M, Van Belle P, Clement F, Hanon E, Wettendorff M, Garcon N, Leroux-Roels G. Vaccine. 2008;26:1375–1386. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Von Eschen K, Morrison R, Braun M, Ofori-Anyinam O, De Kock E, Pavithran P, Koutsoukos M, Moris P, Cain D, Dubois MC, Cohen J, Ballou WR. Hum Vaccin. 2009;5:475–482. doi: 10.4161/hv.8570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Vellas B, Black R, Thal LJ, Fox NC, Daniels M, McLennan G, Tompkins C, Leibman C, Pomfret M, Grundman M, Team ANS. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2009;6:144–151. doi: 10.2174/156720509787602852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Ragupathi G, Gardner JR, Livingston PO, Gin DY. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2011;10:463–470. doi: 10.1586/erv.11.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Van Braeckel E, Bourguignon P, Koutsoukos M, Clement F, Janssens M, Carletti I, Collard A, Demoitie MA, Voss G, Leroux-Roels G, McNally L. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:522–531. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Agnandji ST, Lell B, Soulanoudjingar SS, Fernandes JF, Abossolo BP, Conzelmann C, Methogo BG, Doucka Y, Flamen A, Mordmuller B, et al. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1863–1875. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The RTS Clinical Trials Partnership S. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001685. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernández-Tejada A, Tan DS, Gin DY. Acc Chem Res. 2016;49:1741–1756. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsuda H, Murakami T, Ikebata A, Yamahara J, Yoshikawa M. Chem Pharm Bull. 1999;47:1744–1748. doi: 10.1248/cpb.47.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oda K, Matsuda H, Murakami T, Katayama S, Ohgitani T, Yoshikawa M. Biol Chem. 2000;381:67–74. doi: 10.1515/BC.2000.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Wang P, Kim YJ, Navarro-Villalobos M, Rohde BD, Gin DY. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:3256–3257. doi: 10.1021/ja0422007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kim YJ, Wang PF, Navarro-Villalobos M, Rohde BD, Derryberry J, Gin DY. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:11906–11915. doi: 10.1021/ja062364i. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Deng K, Adams MM, Damani P, Livingston PO, Ragupathi G, Gin DY. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:6395–6398. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Deng K, Adams MM, Gin DY. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:5860–5861. doi: 10.1021/ja801008m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Adams MM, Damani P, Perl NR, Won A, Hong F, Livingston PO, Ragupathi G, Gin DY. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1939–1945. doi: 10.1021/ja9082842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Chea EK, Fernández-Tejada A, Damani P, Adams MM, Gardner JR, Livingston PO, Ragupathi G, Gin DY. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:13448–13457. doi: 10.1021/ja305121q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Fernández-Tejada A, Chea EK, George C, Pillarsetty N, Gardner JR, Livingston PO, Ragupathi G, Lewis JS, Tan DS, Gin DY. Nat Chem. 2014;6:635–643. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dinda B, Debnath S, Mohanta BC, Harigaya Y. Chem Biodivers. 2010;7:2327–2580. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200800070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang Y, Laval S, Yu B. Adv Carbohyd Chem Biochem. 2014;71:137–226. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800128-8.00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szpilman AM, Carreira EM. Org Lett. 2009;11:1305–1307. doi: 10.1021/ol9000735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Crich D, Yao QJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:8232–8236. doi: 10.1021/ja048070j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ustyuzhanina N, Komarova B, Zlotina N, Krylov V, Gerbst A, Tsvetkov Y, Nifantiev N. Synlett. 2006:921–923. [Google Scholar]; (c) Crich D, Picard S. J Org Chem. 2009;74:9576–9579. doi: 10.1021/jo902254w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Crich D, Sharma I. J Org Chem. 2010;75:8383–8391. doi: 10.1021/jo101453y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nukada T, Berces A, Zgierski MZ, Whitfield DM. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:13291–13295. [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Garcia BA, Poole JL, Gin DY. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:7597–7598. [Google Scholar]; (b) Garcia BA, Gin DY. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:4269–4279. [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Jeong PY, Jung M, Yim YH, Kim H, Park M, Hong EM, Lee W, Kim YH, Kim K, Paik YK. Nature. 2005;433:541–545. doi: 10.1038/nature03201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Finch P, Iskander GM, Siriwardena AH. Carbohydr Res. 1991;210:319–325. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bang SC, Seo HH, Yun HY, Jung SH. Chem Pharm Bull. 2007;55:1734–1739. doi: 10.1248/cpb.55.1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Tolstikov AG, Prokopenko OF, Yamilov RK, Tolstikov GA. Mendeleev Cummun. 1991;1:64–65. [Google Scholar]; (b) Franz AH, Wei YQ, Samoshin VV, Gross PH. J Org Chem. 2002;67:7662–7669. doi: 10.1021/jo0111661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stick RV, Stubbs KA, Tilbrook DMG, Watts AG. Aust J Chem. 2002;55:83–85. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halcomb RL, Danishefsky SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:6661–6666. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen LQ, Kong FZ. Carbohydr Res. 2002;337:2335–2341. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(02)00285-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lichtenthaler FW, Schneideradams T, Immel S. J Org Chem. 1994;59:6735–6738. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt RR, Jung KH. In: Preparative Carbohydrate Chemistry. Hanessian S, editor. Marcel Dekker; New York: 1997. p. 283. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jona H, Mandai H, Mukaiyama T. Chem Lett. 2001:426–427. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mulani SK, Hung WC, Ingle AB, Shiau KS, Mong KKT. Org Biomol Chem. 2014;12:1184–1197. doi: 10.1039/c3ob42129e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.