We read with interest the work by Halmos et al1 in which they describe the effects of dietary FODMAP (Fermentable Oligo-, Di- and Mono- saccharides And Polyols) restriction in patients with IBS on the intestinal microbiota. They showed that low FODMAP intake was associated with reduced total bacterial and lower relative abundance of butyrate-producing Clostridium cluster XIVa, changes that are generally considered unfavourable.2 Therefore, they discourage long-term dietary FODMAP restriction, a suggestion also supported by the recent work of McIntosh and colleagues who noticed unfavourable changes in both microbiota and metabolome of patients with IBS who were on a low FODMAP diet.3 Although low FODMAP intake reduces GI symptoms in almost 75% of patients with IBS, the effects of this diet on the intestinal microbiota might be disadvantageous in the long run.

Combining these observations with the important role for the intestinal microbiota in IBS pathogenesis,4 we report here faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) as an alternative to FODMAP restriction in patients with IBS. We applied FMT in 12 refractory IBS patients (Rome III criteria) with intermittent diarrhoea and severe bloating, and mapped the associated microbiota changes after therapy 5 6 (see online supplementary file). In our cohort, the median disease duration was 14.5 years (5–40) and patients (8/12 female) had undergone at least three conventional treatment attempts prior to inclusion (see online supplementary table S1). Consecutive faecal samples were collected from the last seven patients for microbiome analyses.

gutjnl-2016-312513supp001.pdf (87KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2016-312513supp002.pdf (34.8KB, pdf)

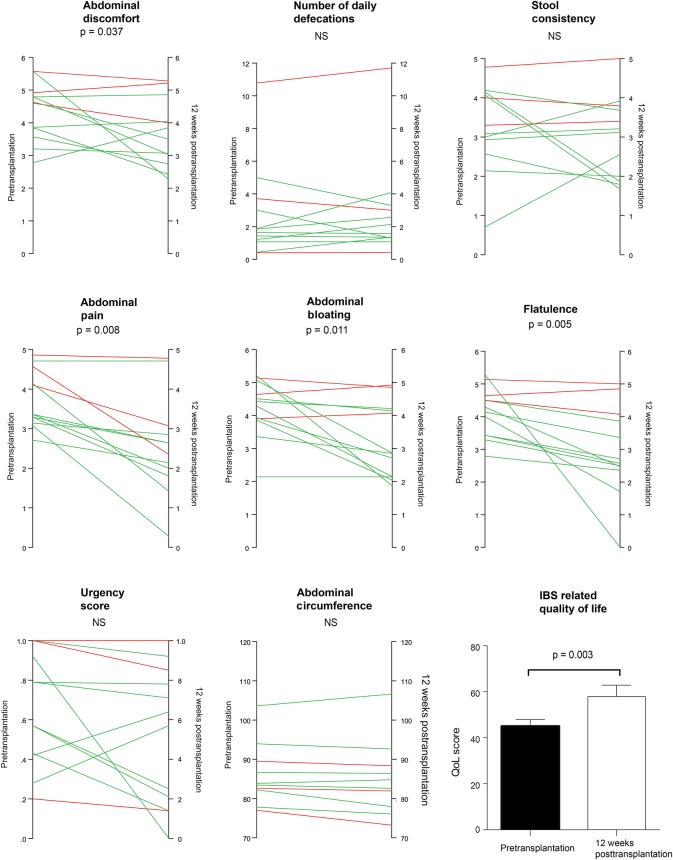

In this study nine patients (75%) met the primary endpoint being: ‘adequate relief of global IBS symptoms and abdominal bloating’, 12 weeks after FMT. A significant reduction in general abdominal discomfort (−21%), abdominal pain (−26%), bloating (−35%) and flatulence (−37%) was reported. The overall quality of life also improved significantly (+12.9%) (see online supplementary tables S2 and S3, figure 1). Responders were followed up and 7/9 (78%) still reported significant relief of IBS symptoms after a period of 1 year, suggesting long-lasting effects of FMT.

Figure 1.

Changes in specific IBS-related symptoms at week 12 post-FMT. Lines in green represent responders to the FMT, lines in red represent non-responders. Wilcoxon's signed ranks test. FMT, faecal microbiota transplantation.

gutjnl-2016-312513supp003.pdf (45.4KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2016-312513supp004.pdf (42.3KB, pdf)

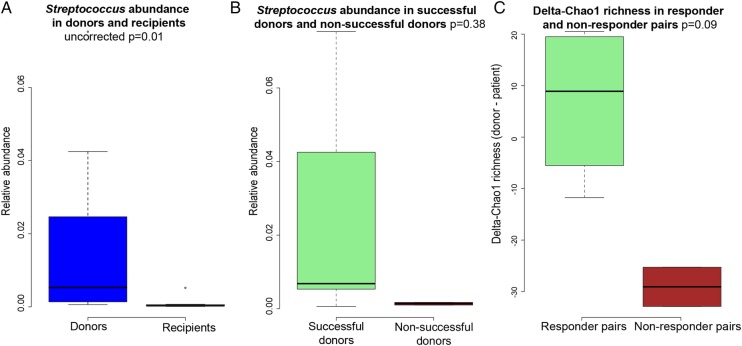

Microbiota analysis showed no community differences between patients and donors and no difference in microbial dissimilarity between patient–donor responders and non-responder pairs at baseline. However, we observed a trend of higher Streptococcus counts in donors compared with patients (uncorrected p=0.011) and successful donors tended to have higher baseline counts of Streptococcus compared with non-successful donors (figure 2). Interestingly, we also observed a trend of higher enrichment potential in responders compared with non-responders (figure 2). In line with earlier observations in IBD, the median number of successfully transferred phylotypes was also higher in responders (n=6) versus non-responders (n=2.5) (not significant).7

Figure 2.

Baseline microbial differences between donors and patients and microbial differences according to the response to treatment. (A) The observed tendency for higher Streptococcus counts at baseline in donors compared with patients (uncorrected p=0.011). (B) The trend for higher baseline counts of Streptococcus in successful donors compared with non-successful donors. (C) The differences in delta richness (donor minus patient) values between patients with IBS responding to the FMT versus non-responders (Chao1 richness: p=0.095). FMT, faecal microbiota transplantation.

With this open-label FMT study in patients with IBS, we found a similar response rate as for the low-FODMAP diet. Interestingly, positive effects on IBS-related symptoms seem to be linked to changes in the intestinal microbiota due to FMT. This study suggests FMT as a possible treatment option for IBS and supports correlations between abnormalities in the intestinal microbiota and IBS.

The main limitation of our study is its design as an open-label trial. Of note, however, placebo response rates in similar IBS patient cohorts are reported to be approximately 37.5%, which is considerably lower than the response rate of 75% that we report here.8 Nonetheless, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, addressing also microbial changes, are necessary to provide clear answers about the applicability of FMT in IBS and are currently on-going both in our centre (NCT02299973) and elsewhere (NCT02092402; NCT02154867).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Saskia Van Damme, Thalita Van Hulle, Jolien De Keukelaere, Joris Van Caenegem, Jen Vandevijver, Kimberley Claus, Tine De Lepeleire, Saskia Verhofstede, Petra Premereur, Leen Rymenans and Chloe Verspecht for technical support.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Marie Joossens at @JoossensM

Contributors: Study concept and design: TH, MDV, DDL, MJ, and JR. Acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: TH, DDL, MJ, JW, JB, and JR. Drafting of the manuscript: TH and MJ. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Statistical analysis: TH, JW, and MJ. Obtained funding: DL, MDV, MJ, BV, JB, HVB, DDL and JR. Administrative, technical or material support: TH, JB, MJ, HVB, BV, JR, and DL. Study supervision: DDL, MDV, BV, and JR. Final approval of manuscript as submitted: all authors. Guarantors of the article: DDL and JR.

Funding: TH, MJ, DL, BV and JW are supported by fellowships from the Research Foundation—Flanders (FWO).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Ethical Committee University Hospital Ghent.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data are available to TH, MJ, JR and DL.

References

- 1.Halmos EP, Christophersen CT, Bird AR, et al. Diets that differ in their FODMAP content alter the colonic luminal microenvironment. Gut 2015;64:93–100. 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Le Chatelier E, Nielsen T, Qin J, et al. Richness of human gut microbiome correlates with metabolic markers. Nature 2013;500:541–6. 10.1038/nature12506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McIntosh K, Reed DE, Schneider T, et al. FODMAPs alter symptoms and the metabolome of patients with IBS: a randomised controlled trial. Gut 2016; Published Online First 14 March 2016. 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-311339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simrén M, Barbara G, Flint HJ, et al. Intestinal microbiota in functional bowel disorders: a Rome foundation report. Gut 2013;62:159–76. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ringel-Kulka T, Benson AK, Carroll IM, et al. Molecular characterization of the intestinal microbiota in patients with and without abdominal bloating. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2016;310:G417–26. 10.1152/ajpgi.00044.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeffery IB, O'Toole PW, Öhman L, et al. An irritable bowel syndrome subtype defined by species-specific alterations in faecal microbiota. Gut 2012;61:997–1006. 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vermeire S, Joossens M, Verbeke K, et al. Donor species richness determines faecal microbiota transplantation success in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohn Colitis 2016;10:387–94. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah E, Pimentel M. Placebo effect in clinical trial design for irritable bowel syndrome. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2014;20:163–70. 10.5056/jnm.2014.20.2.163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

gutjnl-2016-312513supp001.pdf (87KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2016-312513supp002.pdf (34.8KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2016-312513supp003.pdf (45.4KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2016-312513supp004.pdf (42.3KB, pdf)