Abstract

Sterile Alpha Motif and HD Domain Protein 1 (SAMHD1) is a unique enzyme that has important roles in nucleic acid metabolism, viral restriction, and the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases and cancer. Although much attention has been focused on its dNTP triphosphohydrolase activity in viral restriction and disease, SAMHD1 also binds to single-stranded RNA and DNA. Here we utilize a UV crosslinking method using 5-bromodeoxyuridine-substituted oligonucleotides coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) to identify the binding site for single-stranded nucleic acids (ssNA) on SAMHD1. Mapping cross-linked amino acids on the surface of existing crystal structures demonstrated that the ssNA binding site lies largely along the dimer-dimer interface, sterically blocking the formation of the homotetramer required for dNTPase activity. Surprisingly, the disordered C-terminus of SAMHD1 (residues 583–626) was also implicated in ssNA binding. An interaction between this region and ssNA was confirmed in binding studies using the purified SAMHD1 583–626 peptide. Despite a recent report that SAMHD1 possesses polyribonucleotide phosphorylase activity, we did not detect any such activity in the presence of inorganic phosphate, indicating that nucleic acid binding is unrelated to this proposed activity. These data suggest an antagonistic regulatory mechanism where the mutually exclusive oligomeric state requirements for ssNA binding and dNTP hydrolase activity modulate these two functions of SAMHD1 within the cell.

Graphical abstract

Interest in Sterile Alpha Motif and HD Domain Protein 1 (SAMHD1) was initially sparked by the observation that mutations at this locus cause Aicardi-Goutières Syndrome (AGS)1, an autoimmune disease known to result from disrupted nucleic acid metabolism2. Further studies found that SAMHD1 is also a potent restriction factor of HIV-1 infection in macrophages and dendritic cells3,4, bolstering the connection between SAMHD1 and immune responses. The first inkling of its mechanism came from the discovery that the HD domain of SAMHD1 has GTP-dependent dNTP triphosphohydrolase activity, capable of catalyzing the hydrolysis of all four canonical dNTPs to the deoxynucleoside and triphosphate5,6. Subsequent biochemical studies elucidated a complicated activation mechanism where the binding of activating nucleoside triphosphates to two activator sites on each monomer (A1 and A2) drives formation of the active dNTPase tetramer7,8. Remarkably, the activated form of SAMHD1 has twelve bound nucleotides: four dNTPs at each of its four catalytic sites and eight activating nucleotides bound to A1 and A2 activator sites8. Several crystallographic studies of the isolated HD domain from SAMHD1, including structures of the apo dimer5 and various dNTP-bound tetramers9,10, support this activation mechanism.

The dNTPase activity of SAMHD1 is widely believed to result in restriction of DNA viruses and retroviruses by depleting the dNTP pools required for viral DNA synthesis, particularly in resting immune cells that do not carry out host DNA replication11,12. SAMHD1 has also been shown to inhibit the replication of endogenous human LINE-1 retroelements via a mechanism that requires an intact dNTP hydrolase active site13,14. It is speculated that the constitutive production of interferon alpha in a AGS patients stems from an immune reaction to intracellular retroelement replication intermediates, providing a plausible mechanistic link between SAMHD1 dysfunction and autoimmunity2.

In addition to its dNTP hydrolase activity, it has been reported by two groups that SAMHD1 has single-stranded (ss) DNA or RNA exonuclease activity15,16. Ryoo et al. reported that the restriction of HIV-1 infection by SAMHD1 stems from an active site-dependent RNA exonuclease activity rather than dNTP pool depletion16. However, recent work in our laboratory showed that no DNA or RNA exonuclease activity could be attributed to the SAMHD1 active site17, consistent with several earlier reports5,18. Subsequent work by Ryoo et al has asserted that the discrepant results arise from SAMHD1 having a polyribonucleotide phosphorylase activity rather than a conventional hydrolytic ribonuclease activity (i.e. inorganic phosphate is the nucleophile rather than water)19. An understanding of possible additional functions of SAMHD1 is important because it has been reported that dNTPase deficient mutants are still capable of restricting infection of HIV-116.

The structural basis and biological function of the ssNA binding activity of SAMHD1 remains enigmatic. Despite the availability of many structures and sequences of HD proteins for structural and phylogenetic comparison, little insight into the nucleic acid binding site is provided. To address this shortcoming, we used photochemical crosslinking20 of SAMHD1 to 5-bromodeoxyuridine-containing ssDNA to identify the nucleic acid binding site of full-length human SAMHD1 using mass spectrometry. The crosslinking results indicate that ssDNA binding prevents the formation of SAMHD1 tetramers by binding to the dimer-dimer interface on free monomers and dimers thereby inhibiting the dNTPase activity of the enzyme. Further, we were unable to measure any polyribonucleotide phosphorylase activity in the presence of phosphate and ssRNA, indicting that the SAMHD1 complexes with ssNA do not possess such an activity. In light of this mechanism of ssNA binding, possible cellular functions are considered.

METHODS

Oligonucleotides

The BrdU-containing DNA oligonucleotide was ordered from Eurofins. All other DNA oligonucleotides were obtained from IDT. The FAM-labeled RNA 40mer was obtained from IDT, and the unlabeled RNA 90mer was produced by in vitro transcription with T7 RNA polymerase. For the sequences of all DNA and RNA used, see Supplementary Table S1.

Cloning and Purification of SAMHD1 Variants

The SAMHD1 variant constructs were generated by QuikChange Mutagenesis of the published bacterial expression plasmid8. All mutations were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Unless otherwise noted, proteins were expressed as N-terminal His10 fusions in E. Coli, purified with Ni-NTA affinity resin, cleaved from the tag with PreScission Protease, and further purified by Mono S cation exchange chromatography, as described previously8.

A C-terminal peptide corresponding to residues 583–626 of SAMHD1 was generated by polymerase chain amplification, followed by ligation into pGEX-6p-1 to generate a plasmid for the expression of GST fusion proteins. The pGEX-6p-1 plasmids were transformed into BL21DE3 E. Coli, grown at 37 °C to an OD of 0.5, reduced to 22 °C, and induced with 0.25 mM IPTG, grown for an additional 24 hours, and the pellets isolated by centrifugation. The cells were lysed as described previously8, then purified by glutathione sepharose affinity resin. The GST tag was cleaved by treatment with PreScission Protease, the free tag and protease were removed by glutathione sepharose resin, purified by Superdex-200 size exclusion chromatography, and the pure peptide was concentrated using a 3 kDa MWCO centrifugal concentrator. The peptide was stored at −80 °C in buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 10% glycerol.

UV Crosslinking

The crosslinking reactions were carried out on ice in 1 cm by 1 cm quartz cuvettes on a UV transilluminator equipped with 6 USHIO 8W UV-B (306 nm) lamps. The buffer consisted of 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, and 1 mM EDTA, with 1 mM MgCl2 substituted for EDTA in reactions with nucleotides. The protein and BrdU DNA were added to a final concentration of 5 µM each. For analytical reactions, the solution was exposed to UV light for a given period of time, then quenched by removal and dilution into SDS loading buffer. For the preparative scale reactions, a 1 mL volume reaction was exposed to UV light for 2 minutes, then prepared for mass spectrometry analysis.

Trypsin Digestion

The UV-crosslinked samples (or uncrosslinked controls) were adjusted to 1 M urea, reduced with 5 mM DTT at 55 °C for 30 minutes, cooled to room temperature and alkylated with 14 mM iodoacetamide for 1 hour in the dark, then quenched with 10 mM DTT for 15 minutes at room temperature in the dark. To 360 µg of SAMHD1, 10 µg of trypsin was added and the reaction was incubated at 37 °C overnight.

Fe3+-IDA Enrichment of Crosslinked Peptides

Fe3+-IDA resin was prepared from uncharged IDA resin (Bio-Rad) as described previously21. The tryptic peptides from above were diluted five-fold in 100 mM acetic acid, then run through 2 mL of Fe3+-IDA resin. The flow-through was run through the resin an additional two times to ensure complete binding, and the resin was washed in turn with 10 mL of: 100 mM acetic acid, 3:1 100 mM acetic acid:acetonitrile, 1:1 100 mM acetic acid:acetonitrile, 1:3 100 mM acetic acid:acetonitrile. The DNA-crosslinked peptides were eluted from the resin with 10 mL elutions of: pH 10.5 aqueous NH4OH, 1:1 pH 10.5 aqueous NH4OH:acetonitrile, and twice more with pH 10.5 aqueous NH4OH. The elutions were pooled and evaporated to dryness.

Nuclease Digestion of DNA-Peptide Conjugates

The eluted DNA-peptide and free DNA species from the Fe3+-IDA resin were resuspended in 0.5 mL of buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 0.5 mM TCEP. To this solution 2 µg of phosphodiesterase I from Crotalus adamanteus venom (USB), 5 U of shrimp alkaline phosphatase (NEB), and 10 U of Turbo DNase (Ambion) were added and the reaction was incubated at 37 °C overnight. The solution was then evaporated to dryness.

Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Methods

The dried nuclease digestion was desalted using C18 cleanup columns containing 8 mg of C-18 resin (Pierce), according the manufacturer instructions. The eluted sample was evaporated to dryness, resuspended in 10% acetonitrile in water with 0.1% formic acid, and analyzed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. The LC/MS analysis was performed on a Dionex Ultimate 3000 UHPLC with an Agilent Polaris C18 100 × 2 mm column coupled to a Thermo Scientific Q-Exactive orbitrap mass spectrometer. A gradient of 0.1% formic acid in water to 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile was used. The mass spectrometer was run with a Top-10 data-dependent acquisition in positive ion mode. The normalized collision energy was set to 27%, which resulted in robust fragmentation of the peptide bonds and consistent cleavage of the glycosidic bond in the crosslinked nucleotides, leaving a uracil modification in the fragment ions.

Mass Spectrometry Data Analysis

The raw mass spectrometry data was analyzed with Thermo Scientific Proteome Discoverer. The software was set to search for tryptic peptides of the recombinant SAMHD1 (containing an additional GPH tripeptide at the N-terminus), with a variable acetyl modification on the N-terminus and a static carbamidomethyl modification on cysteine residues. Up to two missed cleavages were allowed to account for decrease cleavage efficiency due to nearby crosslinked oligonucleotides. To identify crosslinked peptides, variable modifications corresponding to the dUpdT dinucleotide (530.10501 Da) or dUpdTpdT trinucleotide (834.15104 Da) were included. We did not observe any nucleoside or tetranucleotide modifications. Spectra with a parent ion mass corresponding to dinucleotide or trinucleotide-modified peptide were manually inspected to identify fragment ions containing a uracil modification (110.01162 Da). Where applicable, these peaks were manually annotated on the spectra.

Gel Electrophoresis of SAMHD1-DNA Complexes

The SAMHD1-crosslinked and peptide-crosslinked BrdU DNA were separated from the free BrdU DNA on Bio-Rad TGX 4–20% acrylamide gels run in Tris-Glycine-SDS buffer. In the case of 32P-labeled samples, the gels were dried and exposed to storage phosphor screen overnight. The relative quantity of DNA in the free, peptide-crosslinked, and SAMHD1-crosslinked bands was quantified by densitometry with ImageJ22. For silver stained gels, the previously published procedure was followed8.

Determination of Oligomeric State

To measure the relative levels of the monomeric, dimer, and tetrameric forms of SAMHD1, samples were crosslinked with glutaraldehyde, run on denaturing Novex bis-tris 4–12% acrylamide gels, and visualized with silver staining. This published procedure has been shown to agree well with analytical ultracentrifugation measurements of SAMHD1 oligomers8. The relative quantity of monomer, dimer, and tetramer were quantified by densitometry with ImageJ22.

DNA Binding Measurements by Fluorescence Anisotropy

The binding of SAMHD1 to fluorescein (FAM)-labeled oligonucleotides was monitored through fluorescence anisotropy, as described previously17. The buffer was 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA to stay consistent. Unless otherwise noted in the text, the concentration of oligonucleotide was fixed at 50 nM. The data were fit to a quadratic binding equation to account for ligand depletion17. No corrections for changes in the fluorescence intensity of the fluorophore labels were required based on the emission spectra of free and bound oligonucleotides. Previous studies have established that labeled and unlabeled oligonucleotides bind competitively and with similar C0.5 values17.

Melting Temperatures for Mutant and Wild-type SAMHD1

SAMHD1 or variants (5 µM) in 50 mM HEPES-HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, and 1 mM EDTA were placed in sealed quartz cuvettes and the fluorescence (280 nm excitation, 330 and 350 nm emission) was recorded as the sample was heated from 20 to 85 °C (2°C/min). The ratio of the emission at 350 nm to 330 nm was plotted as a function of temperature. The data were fit to a sigmoidal curve and the melt temperature was determined from the mid-point of the thermal transition.

dNTPase Activity Measurements of Mutant Proteins

For the wild-type and mutant proteins, the dNTP hydrolase measurements were made by RP-C18 TLC with 3H-labeled dGTP. The conditions were 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dGTP, and 0.5 µM SAMHD1. The dGTP hydrolase rates were determined as described previously8, and normalized to the wild-type enzyme measured at the same time.

Polynucleotide Phosphorylase Activity Measurements

To assess for the presence of a 3’-5’ phosphorolysis activity of SAMHD1, a ssRNA 20mer was labeled with 32P on the 5’ end. Reactions were performed in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, with the addition of phosphate (as K2HPO4, pH 7.5) using 1 µM ssRNA 20mer and 0.5 µM SAMHD1. As a positive control, a reaction with 0.1 µM human polyribonucleotide phosphorylase was conducted using the same substrate and buffers (Sigma-Aldrich). The reactions were quenched at the indicated times by addition of one volume of formamide loading buffer, and the products were resolved by electrophoresis using a urea denaturing 20% polyacrylamide gel with detection by autoradiography. To confirm full-activity of the enzyme, parallel dNTPase activity measurements were made as described above under identical buffer conditions using the same SAMHD1 concentration with 1 mM 8-[3H] dGTP.

To directly assess whether phosphate is utilized in the degradation of RNA, we also carried out reactions in a buffer containing radiolabeled 32P inorganic phosphate (10 mM total phosphate, specific radioactivity = 100 mCi/mmol), 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 5 µM SAMHD1 or 1 µM polynucleotide phosphorylase and 1 mg/mL of unlabeled poly(A) RNA (Sigma-Aldrich). At indicated times over an 8h period, reactions were quenched by spotting 1 µL on a PEI-Cellulose TLC plate. The plates were developed in 1 M LiCl to separate the product nucleoside diphosphate from the phosphate substrate, dried, and visualized by autoradiography.

RESULTS

5-Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) Crosslinking Method

In previous studies of SAMHD1 binding to ssDNA, we found that ~60nt were required for highest affinity binding17. Accordingly, we designed a 59nt ssDNA containing thymidine and four BrdU bases evenly spaced throughout the sequence (BrdU-DNA). Upon irradiation with UV light, BrdU is excited to a triplet state which undergoes a radical-mediated reaction with nearby aromatic amino acids, ultimately forming a protein-DNA covalent bond 23.

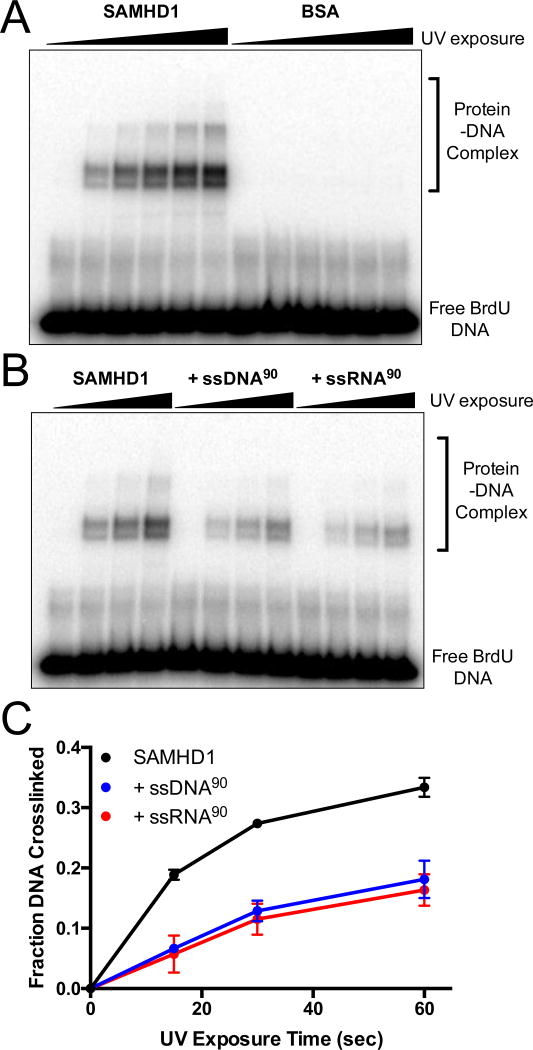

To confirm the specificity of this reaction, crosslinking was carried out with BrdU-DNA in the presence of SAMHD1 or BSA. BSA is an appropriate negative control because it has a similar amino acid composition and molecular weight of the SAMHD1 monomer, but does not have nucleic acid binding activity. When the BrdU-DNA is 5’-labeled with 32P, the free DNA and SAMHD1-crosslinked DNA are easily visualized by phosphorimaging after separation using SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1A). With increasing UV irradiation, a substantial fraction (~30%) of the total DNA migrated in cross-linked complexes with SAMHD1, while no crosslinking was observed with the BSA control protein using the same UV exposure time. Similar results were obtained using unlabeled oligonucleotide and silver staining to directly visualize the free protein and protein-DNA complex (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 1. Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) specifically crosslinks SAMHD1.

(A) SAMHD1 or BSA (5 µM) and 32P-labeled BrdU-DNA (5 µM) were mixed, exposed to UV light for 0 to 2 minutes, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. (B) SAMHD1 (5 µM) and 32P-labeled BrdU DNA (5 µM) were UV irradiated in the presence or absence of unlabeled competitor ssDNA or ssRNA 90mer (5 µM), and analyzed by SDS PAGE. (C) Densitometry of the bands for the free DNA and DNA-SAMHD1 complexes in (B) was used to calculate the fraction of BrdU DNA crosslinked to SAMHD1.

To further establish the specificity of crosslinking, UV exposure of SAMHD1 with 32P-BrdU-DNA was performed in the presence of an equal concentration of unlabeled 90mer competitor ssDNA or ssRNA (Fig. 1B). Both ssDNA and ssRNA efficiently competed with 32P-BrdU-DNA for binding to SAMHD1 as revealed by reduced levels of crosslinking over time (Fig. 1C). These results are consistent with our previous studies indicating that ssDNA and ssRNA share the same binding site on SAMHD117. Thus, BrdU-containing ssDNA binds to the same region of SAMHD1 as native single-stranded nucleic acids.

High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry of SAMHD1-Nucleic Acid Complexes

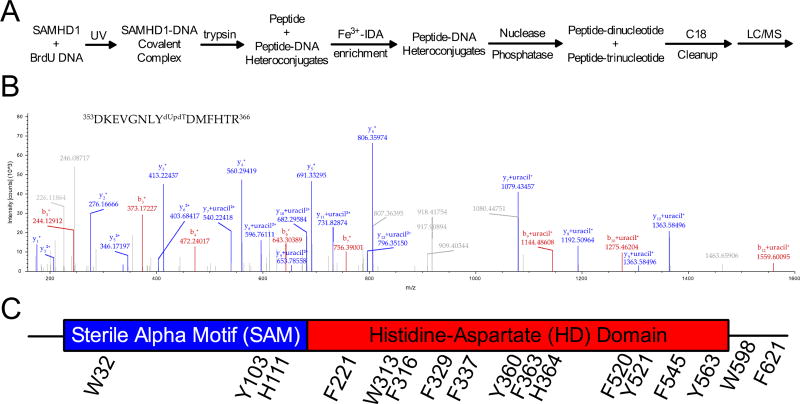

In order to identify the amino acids of SAMHD1 that become cross-linked to BrdU-DNA, and thus are in the proximity of the nucleic acid binding site, we used mass spectrometry-based proteomics (Fig. 2A). In this approach, a reaction of SAMHD1 and BrdU-DNA was exposed to UV light and digested with trypsin to yield peptides and peptide-DNA heteroconjugates. An Fe3+-IDA column was used to select for DNA-crosslinked peptides by taking advantage of the high-affinity of phosphates for Fe3+ ions21,24. The isolated peptide-DNA heteroconjugates were digested with nucleases and phosphatase to yield peptides with di- (dUpdT) or tri-nucleotides (dUpdTpdT) at the original site of crosslinking. Subsequent analysis by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry resulted in high quality, readily interpretable spectra. An example is shown in Fig. 2B, and the entirety of the spectra are provided and assigned in the Mass Spectrometry Supplement.

Figure 2. Mass spectrometry for the identification of BrdU crosslinks to SAMHD1.

(A) A schematic for mass spectrometry sample preparation. (B) A representative MS2 spectrum from a cross-linked peptide. The parent ion m/z corresponded to the shown peptide with an attached dUpdT dinucleotide and the shown fragment ions unambiguously identify Y360 as the crosslinked residue. Upon fragmentation, b and y ions of the peptide were observed, and the di- or trinucleotide modification fragmented to uracil. (C) All of the cross-linked amino acids observed in the mass spectrometry studies are shown on the linear domain architecture of SAMHD1.

Overall, 17 sites of crosslinking could be unambiguously identified based on the parent ion mass and the presence of uracil (the fragmentation product of the original di- or tri-nucleotide) in the b and y fragment ions. Nearly all of the crosslinks fell within the structured region of the HD domain (Fig. 2C). Two additional cross-linked amino acids (W598 and F621) were located in the disordered C-terminus (see below) and two were identified in the linker region between the HD and SAM domains (Y103, H111). In addition, a single site of crosslinking was identified in the amino terminal region of the SAM domain (W32). Since there are no structures of the full-length enzyme, it is not possible to know whether the site in the SAM domain is near the other sites of crosslinking in three-dimensional space. Nevertheless, we have shown that deletion of the entire SAM domain had little effect on ssNA binding17, which at the very least indicates a non-essential interaction with this domain. We cannot eliminate the possibility that crosslinking of highly exposed aromatic groups in flexible regions of the protein may occur adventitiously after crosslinking to the groups in the structured region of the HD domain (however, see below for C-terminus binding).

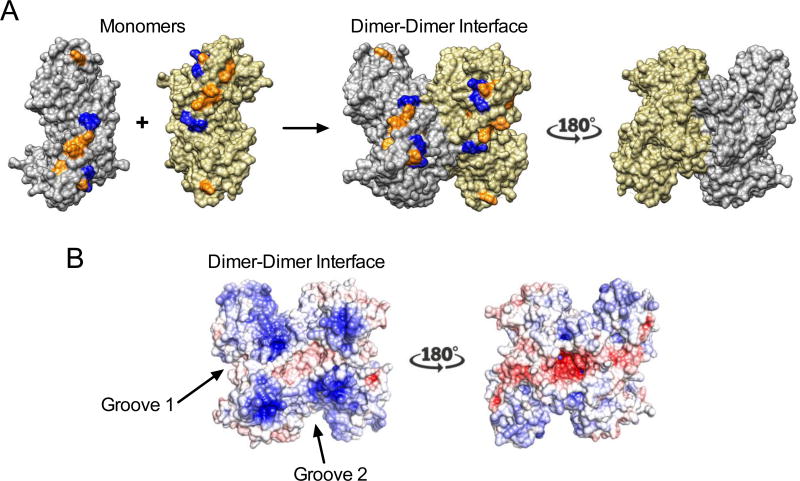

Mapping the Cross-linked Sites

Mapping the sites of crosslinking onto the dimer crystal structure of the SAMHD1 HD domain (PDB 3U1N) reveals that most are exposed aromatic groups that cluster at the dimer-dimer interface (orange residues in Fig. 3A)25. Consistent with the lack of crosslinking to BSA, specificity is evident because there are numerous surface aromatic amino acids on the solvent-exposed faces of the tetramer that showed no labeling (see Supplementary Fig. S2). Binding of ssNA at the dimer-dimer interface provides a structural explanation for our previous findings that (i) RNA binding inhibits dNTPase activity, and (ii) high dNTP concentrations that promote tetramerization inhibit ssNA binding17.

Figure 3. Structural analysis of the BrdU cross-linked regions.

(A) Cross-linked aromatic amino acids (orange) are mapped onto the crystal structure of SAMHD1 (PDB 3U1N): F221, W313, F316, F337, Y360, H364, F520, F545, Y563. The Arg residues that have been mutated in this study are shown in blue (R333, K336, R371, R372). (B) Electrostatic surface potential of the HD domain dimer shown using the same two views in (A). The potential was obtained from Poisson-Boltzmann (PB) electrostatics calculations using the APBS tool in Chimera25. The two grooves that are flanked by the crosslinking sites in the monomers and dimer are indicated.

Since SAMHD1 exists as a ~1:2 mixture of monomers and dimers under the conditions of the crosslinking experiment8, the results do not provide a readout of whether ssNA binds to monomer, dimer or both forms of SAMHD1. However, our previous AFM and biochemical studies determined that a 57nt ssDNA can accommodate two SAMHD1 monomers17. Thus, two monomers could bind to the 59nt DNA used in the crosslinking studies, or alternatively, a preformed dimer. The second alternative is most probable because the dimer is more abundant under the conditions of the current study8 and there would be an entropic advantage for dimer binding as opposed to two monomers.

We mapped the electrostatic surface potential onto the dimer structure (PDB 3U1N) and found that the cross-linked aromatic amino acids cluster near grooves with positive charge potential (blue surfaces, Fig. 3B), which provides a compatible electrostatic environment for binding the polyanionic backbone of ssNA. Two plausible grooves for the binding of nucleic acids are indicated. One of the grooves exists in each monomer (groove 1, Fig. 3B), but the second groove is created upon dimer formation (groove 2, Fig. 3B), suggesting that the sites that flank groove 2 may only be crosslinked in the nucleic acid-bound dimer.

Biochemical Validation of Crosslinking Sites

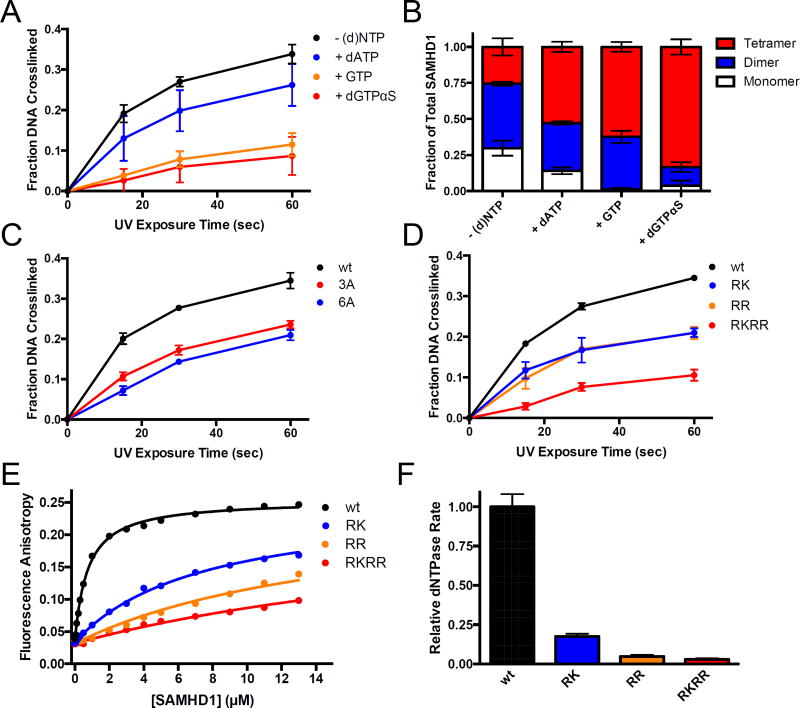

To further confirm that ssNA binds specifically at the dimer-dimer interface, we performed the crosslinking reaction between BrdU-DNA and SAMHD1 in the presence of nucleotides (dATP, GTP, dGTPαS) that are known to induce varying amounts of tetramer and quantified the complexes after various times of UV irradiation using SDS-PAGE (Fig. 4A, Supplementary Fig. S3A)8. Based on our previous work, dATP is known to have little effect on oligomerization, but guanine nucleoside triphosphates are expected to promote tetramerization, with dGTPαS being most potent because it can bind to the A1 and A2 activator sites as well as the catalytic site8,17. The UV crosslinking results in Figure 4A using dATP, GTP and dGTPαS match these expectations closely.

Figure 4. Biochemical validation of the mass spectrometry crosslinking results.

(A) BrdU crosslinking reactions were performed with SAMHD1 in the presence of dATP, GTP, or dGTPαS to induce oligomerization (1 mM each) and the fraction of total DNA crosslinked to SAMHD1 was quantified. (B) The oligomeric state of SAMHD1 under the conditions in (A) was assessed by glutaraldehyde crosslinking and quantified by densitometry. (C) BrdU crosslinking reactions were performed with wild-type SAMHD1, or the 3A and 6A alanine mutants (see text) and the fraction of the total DNA cross-linked to the protein was quantified. (D) BrdU crosslinking reactions with wild-type SAMHD1 or the indicated glutamate charge-reversal mutants RK, RR, and RKRR (see text). The fraction of the total DNA cross-linked to the protein at each time point was quantified by densitometry. (E) Increasing anisotropy of a fluorescein-labeled dT60 DNA oligonucleotide as a function of added wt or mutant SAMHD1. (F) The normalized dNTP hydrolase activity of wt SAMHD1 and the indicated mutants was determined using 1 mM dGTP as the substrate.

We also used our glutaraldehyde protein crosslinking method8 to measure the relative amounts of SAMHD1 monomer, dimer, and tetramer in the presence of each nucleotide (Supplementary Fig. S3B). As previously observed, the amount of tetramer increases from ~25% of total SAMHD1 without any added nucleotides to ~85% in the presence of 1 mM dGTPαS (Fig. 4B). By comparing the BrdU crosslinking efficiency with level of tetramer present (i.e Fig. 4A and 4B), it is clearly apparent that BrdU crosslinking is anti-correlated with tetramer formation. Thus, we conclude that the tetrameric form of SAMHD1 does not bind ssNA.

To confirm the sites of crosslinking directly, we generated mutant SAMHD1 proteins in which three (F337A, Y360A, Y521A; “3A”) or six (F329A, F337A, Y360A, H364A, Y521A, F545A; “6A”) of the cross-linked aromatic amino acids were replaced with an alanine residue that is not susceptible to BrdU crosslinking. Both the 3A and 6A proteins showed significantly less UV crosslinking with BrdU ssDNA, confirming the dimer interface as the target of ssNA binding (Fig. 4C, Supplementary Fig. S3C). Importantly, the loss of BrdU crosslinking was not attributable to gross destabilization of SAMHD1 by the mutations because the mutants were still able to dimerize in response to nucleotides (Supplementary Fig. S3D). In addition, we performed thermal melting assays by monitoring changes in tryptophan fluorescence to demonstrate that the 3A and 6A mutants were equally, or in some cases, even more stable than the wild-type enzyme in the absence of nucleotides (Supplementary Fig. 4A). As expected, the 3A and 6A proteins were not able to form tetramers in response to dGTPαS, because hydrophobic packing interactions at the interface have been disrupted26.

Charge Reversal Mutations at the Dimer-Dimer Interface Decrease ssNA Affinity

We noted that two patches of positively charged amino acids were in the vicinity of the cross-linked sites, suggesting that these residues might interact with the anionic phosphodiester backbone of nucleic acids (Fig. 3A, blue residues). To evaluate the contribution of these residues to ssNA binding, we generated the R333E/K336E (“RK”), R371E/R372E (“RR”), or R333E/K336E/R371E/R372E (“RKRR”) charge reversal mutations. As expected, the crosslinking between BrdU-DNA and these mutants was significantly compromised, with the most dramatic effect being observed for the quadruple mutant (Fig. 4D, Supplementary Fig. S3E). Because these mutations replace one surface charge with another, they are not expected to have a significant destabilizing effect on protein structure. This was confirmed in thermal melting assays where the RK, RR, RKRR, and wild-type proteins showed similar melting profiles (Supplementary Fig. S4B). Thus, these residues likely interact electrostatically with ssNA and further validate the location of the ssNA binding site delineated by UV crosslinking and mass spectrometry.

To directly measure the nucleic acid binding of the RK, RR, and RKRR variants, fluorescence anisotropy titrations were performed with 5’ fluorescein-labeled dT60 ssDNA (FAM-dT60). Competition binding experiments and electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) have previously established that the affinity of FAM-labeled ssNA’s measured in fluorescence anisotropy assays matches that of unlabeled DNA and that the fluorescence of the FAM label was not quenched by protein binding17. As expected from the BrdU crosslinking results, the mutations caused a graded decrease in the binding affinity for ssDNA, with the quadruple mutation again showing the most significant effect (Fig. 4E). The concentration of SAMHD1 required for half-maximal binding (C0.5), increased in the range 10 to 40-fold for these mutations: C0.5 = 0.7 ± 0.1 µM for wild-type SAMHD1; 7.6 ± 0.4 µM for RK; 15 ± 1 µM for RR and 30 ± 2 µM for RKRR. As expected, the dNTP hydrolase activity of the charge-reversal mutations is also significantly decreased (Fig. 4F). As above with the 3A and 6A mutations, glutaraldehyde crosslinking studies showed that these mutants were significantly compromised in their abilities to form tetramer, as expected from their location at the dimer-dimer interface (Supplementary Fig. S3F). Thus, the binding site mutations recapitulate the effects of ssNA binding.

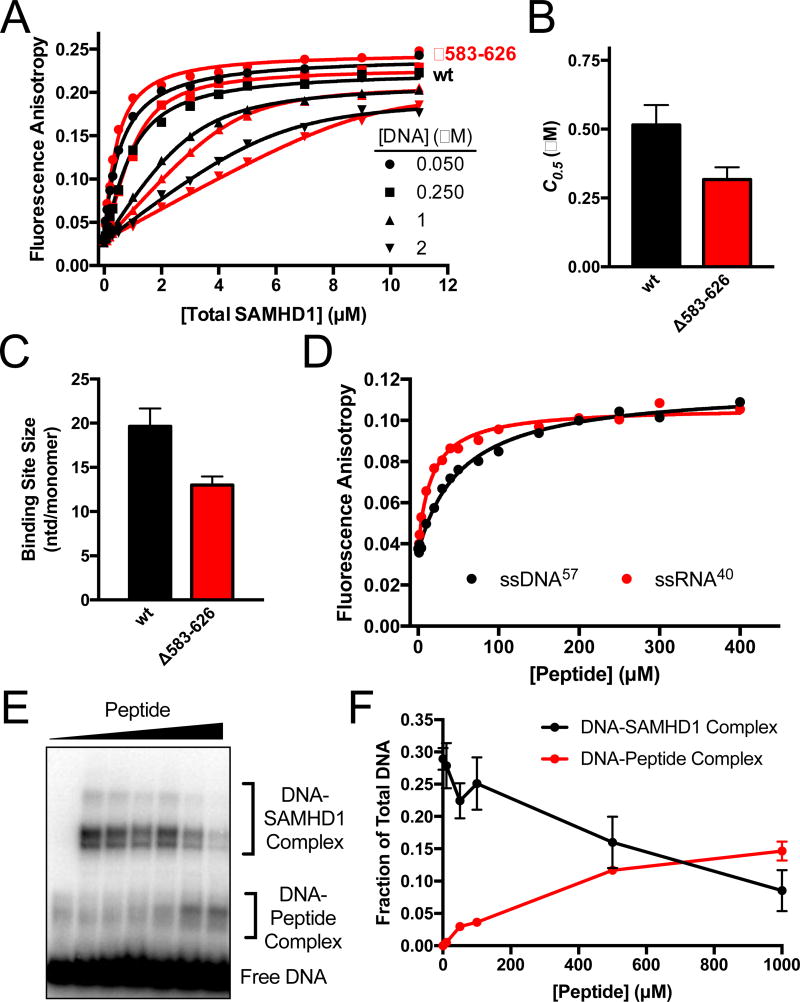

Disordered C-Terminus of SAMHD1 Binds ssDNA and RNA

In addition to the interactions between ssNA and the structured HD domain, we were intrigued that two cross-linked amino acids were identified in the unstructured C-terminus (W598, F621)(Fig. 2C). The C-terminal residues 583–626 are not observed in the crystal structure of the apo-SAMHD1 dimer (PDB ID 3U1N)5, and this region is also largely absent in the electron density maps for the nucleotide-bound tetramer (PDB code 4BZC)9. Although crosslinking of two aromatic groups in a flexible tail could occur adventitiously after tethering to the structured region of the protein (i.e. entropic facilitation), we investigated whether a truncated form of SAMHD1 lacking the residues 583–626 might have a different binding affinity using fluorescence anisotropy measurements of binding to FAM-dT60 ssNA (Fig. 5A). The data were globally fit using a variable-stoichiometry quadratic binding equation17, which allowed for the determination of the binding affinity and an estimation of monomer binding site size in nucleotides (nt) (Fig. 5A). Despite the observed UV crosslinking to two aromatic residues in the C terminal region, the ssNA binding affinity for Δ583–626 was similar to the wild-type protein [C0.5 (wt) = 0.50 ± 0.1 µM; C0.5 (Δ583–626) = 0.30 ± 0.04 µM] (Fig. 5B). However, the apparent binding site size decreased from 20 ± 2 nt/monomer for the wild-type to 13 ± 1 nt/monomer for Δ583–626, suggesting an effect of the tail on the spacing of bound SAMHD1 on single strand nucleic acids (Fig. 5C). The deletion of residues 583–626 had essentially no effect on the capacity of SAMHD1 to oligomerize and caused only a modest two-fold reduction in the dNTP hydrolase rate, confirming that this region is not essential for the enzymatic dNTPase function of SAMHD1 (Supplementary Fig. S5A, B). The observance of crosslinking of ssNA to the tail unambiguously establishes that the two entities are in proximity, but the absence of a measurable effect of the C-terminal truncation on ssNA binding suggests that the crosslinking may arise from weak or dynamic interactions of the flexible tail with the bound nucleic acid.

Figure 5. The disordered C-Terminus of SAMHD1 binds ssNA.

(A) Fluorescence anisotropy titrations of the fluorescein-labeled dT60 with wt and Δ583–626 SAMHD1 as a function of DNA concentration. The data were fit to a variable stoichiometry quadratic binding equation17. (B) Comparisons of the concentrations of wt and Δ583–626 SAMHD1 required for half-maximal DNA binding (C0.5). (C) Comparison of the calculated binding site sizes of wt SAMHD1 and Δ583–626 SAMHD1. The sizes are indicated as nt/monomer. (D) Fluorescence anisotropy increases of FAM-dT60 and FAM-ssRNA40 upon binding of a peptide consisting of residues 582–626 of SAMHD. (E) BrdU crosslinking reactions were performed with fixed concentrations of BrdU DNA (5 µM) and SAMHD1 (5 µM), and variable concentrations (0 to 1 mM) of the 582–626 SAMHD1 peptide. (F) Quantification of the DNA-SAMHD1 and DNA-peptide complexes from (F) by densitometry.

The 582–626 peptide consists of an equal number of positively charged (Lys + Arg) and negatively charged (Asp + Glu) amino acids, making it unlikely that the observed binding is driven by gratuitous non-specific electrostatic interactions. To directly test whether the 582–626 peptide has a measurable binding affinity for single-stranded nucleic acids, the isolated 582–626 peptide was expressed, purified, and its binding to the FAM-dT60 ssDNA was measured using fluorescence anisotropy methods (KD of 54 ± 5 µM) (Fig. 5D, black). To confirm that these results were also applicable to single-stranded RNA ligands (ssRNA), the fluorescence anisotropy titrations were repeated with a fluorescein-labeled ssRNA 40mer (Fig. 5E). The binding affinity to ssRNA was about 4-fold greater than ssDNA with KD = 17 ± 2 µM for the isolated 582–626 peptide. Of note, full-length SAMHD1 also has a higher binding affinity for ssRNA17, indicating that both the isolated tail and the HD domain share this preference. The binding of a disordered region to ssRNA has precedent in the structure of the Tobacco Mosaic Virus binding to its RNA genome, but in this case the interaction is strongly mediated by positively-charged amino acids27. We further discuss the possible implications of nucleic acid binding to the C-terminal region in the Discussion.

In a final assessment of the functional properties of the isolated C-terminal tail we tested whether the 582–626 peptide could competitively inhibit UV crosslinking of wt SAMHD1 to BrdU-DNA. Standard BrdU-DNA UV crosslinking reactions were performed using SAMHD1 in the presence of increasing concentrations of the peptide. As anticipated for competitive binding, as the peptide concentration was increased, the UV cross-linked complex between SAMHD1 and ssDNA decreased and a new band appeared corresponding to a cross-linked complex between the peptide and BrdU-DNA (Fig. 5F). We conclude that the isolated free peptide (i) binds ssNA, (ii) disrupts ssNA complexes with full-length SAMHD1, and (iii) becomes crosslinked to the BrdU-DNA in the same manner as when attached to the SAMHD1 protein.

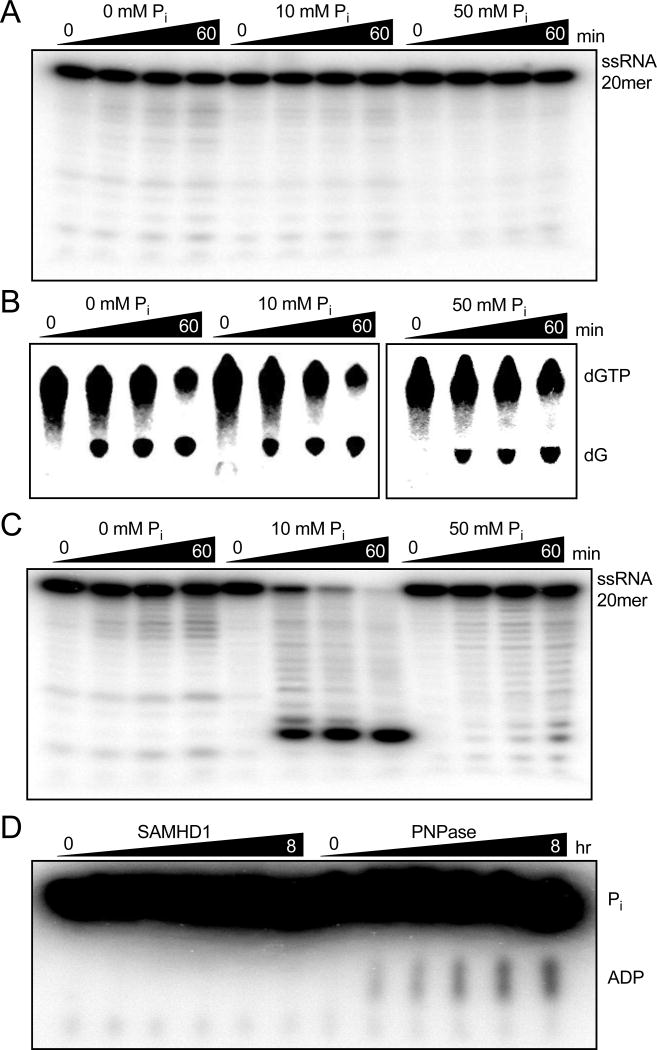

Is ssRNA Binding Associated with a Polyribonucleotide Phosphorylase Activity of SAMHD1?

There have been conflicting reports that SAMHD1 possesses 3’-5’ exonuclease activity5,15–18,28. Moreover, a recent study has reported the detection of a polyribonucleotide phosphorylase activity of the enzyme in the presence of inorganic phosphate19. Although the ssNA binding site described above does not cluster near the known SAMD1 active site, which is consistent with our previous finding that SAMHD1 has neither nuclease or ribonuclease activity17, we felt compelled to investigate whether the newly proposed phosphorylase activity could be detected.

To test for phosphorylase activity, recombinant full-length SAMHD1 was extensively purified by sequential Ni-NTA affinity, cation exchange, and hydrophobic interaction chromotagraphy, as described previously17. In parallel reactions, the purified enzyme was tested for (i) dGTPase activity, and (ii) exoribonuclease or phosphorylase activity using a 5’ 32P-labeled ssRNA 20mer substrate in reactions containing Tris buffer supplemented with increasing amounts of inorganic phosphate. Ribonuclease or phosphorylase activity was virtually undetectable in the presence of zero to 50 mM inorganic phosphate (both activities would result in the accumulation of 3’-truncated oligonucleotide products; Fig. 6A). In contrast, the dGTPase reactions showed robust activity in all buffer conditions tested as judged by resolving the 8-[3H] guanine nucleoside product from the 8-[3H] dGTP substrate by reversed-phase TLC (Fig. 6B). As we previously reported, the trace ribonuclease activity cannot be attributed to SAMHD1 because mutation of the essential active site residues His206 and Asp207 (H206A/D207A) showed an identical activity, which we attribute to trace contamination by a 3′-5′ exonuclease (Supplementary Fig. S6A)17. As a positive control, human polynucleotide phosphorylase was tested under the same conditions and showed substantial degradation of the 5’-32P-labeled RNA in the presence of phosphate (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6. SAMHD1 does not posses hydrolytic or phosphorolytic RNase Activity.

(A) Reactions of 5’ 32P-labeled ssRNA 20mer (1 µM) and SAMHD1 (0.5 µM) were carried out in Tris/KCl/MgCl2 buffer supplemented with the indicated concentration of phosphate and degradation products were resolved by denaturing PAGE. (B) Reactions of 3H-dGTP (1 mM) and SAMHD1 (0.5 µM) carried out under the same conditions as above and the products were resolved by RP-TLC. (C) Reactions were prepared as in (A) but with 0.1 µM human polynucleotide phosphorylase as a positive control. Robust phosphorolytic activity is observed with 10 mM Pi, but is inhibited by high concentrations of Pi as previously reported54 (D) Reactions prepared with Tris/KCl/MgCl2 buffer, 32Pi (10 mM), poly(A) RNA (1 mg/mL), and SAMHD1 (5 µM) or the positive control enzyme human polynucleotide phosphorylase (1 µM) were carried out and the ADP product was resolved from Pi by PEI-Cellulose TLC.

We also employed an orthogonal assay method to confirm that SAMHD1 does not use a phosphate nucleophile to degrade RNA by performing reactions with radioactive 32Pi and unlabeled poly(A) ssRNA (Fig. 6C). In this assay, attack of the radiolabeled phosphate nucleophile at the phosphodiester backbone of the ssRNA substrate should produce a labeled adenine nucleotide diphosphate and an unlabeled n-1 oligonucleotide product. Using PEI-cellulose thin layer chromatography to separate the ADP product from the inorganic phosphate substrate, purified human polyribonucleotide phosphorylase showed a time-dependent increase in radioactive ADP resulting from phosphorolysis of the RNA by 32Pi (Fig. 6D). However, no products were observed even after eight-hours incubation of 0.5 µM SAMHD1 with 50 mM 32Pi and 1 mg/mL poly(A) ssRNA (Fig. 6D).

DISCUSSION

Functional Possibilities for Single-Strand Nucleic Acid Binding by SAMHD1

It is quite paradoxical that cells produce a potent enzyme capable of indiscriminately degrading all dNTPs to nucleoside and tripolyphosphate products. When nucleoside triphosphohydrolase activity is thermodynamically linked with hydrolysis of PPPi to 3Pi by cellular triphophosphatases, the overall process is exergonic and can only be reversed with great energetic expense by the cell29. Thus, it would be expected that the activity of SAMHD1 would be regulated at multiple levels. The possible functional roles for nucleic acid binding by SAMHD1 in cells remain poorly understood and the discussion below is intended to summarize the possibilities in the context of our in vitro findings. We consider distinct scenarios in non-dividing and dividing cells because of the large differences in dNTP pool levels in these cell types.

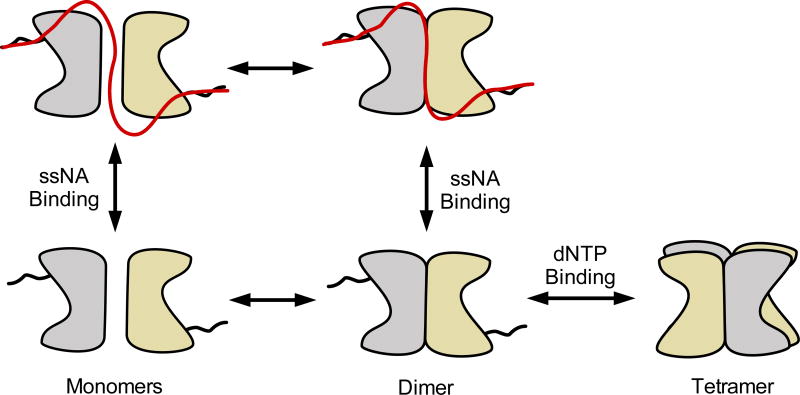

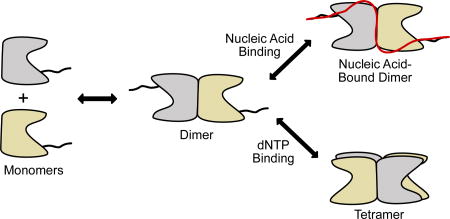

On the basis of these results and previous work17, a model for the interaction of SAMHD1 with single-stranded nucleic acids is proposed (Fig. 7). The underlying facet of the model is that ssNA can bind to both monomer and dimer forms of SAMHD1, but not to nucleotide-activated tetramers. A functional unit for nucleic acid binding consisting of two monomers (or a dimer) is consistent with the previous observation that (i) the binding affinity of SAMHD1 for ssDNA/ssRNA increases with ssNA length until two monomers (one dimer) can be accommodated (>40–50 nt) and, (ii) the major bound form in AFM images has the size of a dimer17. We therefore propose that SAMHD1 dimers serve as the regulatory branch point of its activities: if two dimers bind dNTPs at the A2 activator sites and catalytic sites they will form a dNTPase-competent tetramer, but if ssNA binds to SAMHD1, the complex is pulled into a terminal dimer form that has no dNTPase activity8,30.

Figure 7. Model for antagonistic binding of ssNA and dNTPs to SAMHD1.

SAMHD1 exists primarily as monomers and dimers in solution in the absence of nucleotides. The binding site includes the dimer-dimer interface of the structured HD domain, two positively charged binding grooves (see Fig. 3), and the disordered C-terminus. Binding of ssNA at the dimer-dimer interface prevents tetramer formation. High concentrations of dNTPs competitively shift the equilibrium to the dNTPase-active tetramer form. Although SAMHD1 binds both ssDNA and ssRNA, only the RNA binding activity is likely to be relevant to HIV infection.

There is precedent for regulation of human antiviral restriction factors and HD domain dNTPases by binding to single-stranded nucleic acids. A notable example is the HIV-1 restriction factor APOBEC3G DNA cytidine deaminase (A3G), which is known to aggregate in catalytically inactive high molecular weight complexes with ribonucleic acids31. Like SAMHD1, A3G still retains restriction activity against HIV when its enzymatic activity is abolished by mutagenesis32,33 and it is known to bind both ssRNA and ssDNA with modest affinity. The current view is that A3G binds single strand HIV RNA when co-packaged within the viron where it slowly adopts a high-affinity oligomeric state that can block reverse transcription34. Single strand nucleic acid-mediated regulation of HD domain dNTPase activity has been previously observed with the E. coli dGTP triphosphohydrolase (ecGTPH), an HD domain homolog of SAMHD1 with a hexameric oligomeric state and a different dNTP specificity35,36. However, in the case of ecGTPH, ssNA binding was shown to activate the triphosphohydrolase activity36. Our model suggesting that SAMHD1 can bind single strand nucleic acids in cells is also strongly supported by cellular fluorescence cross-correlation microscopy experiments where SAMHD1 complexes with single-stranded DNA and RNA have been detected in human cells37.

In the case of non-dividing cells, where SAMHD1 is highly expressed and dNTP pools are low11,38,39, the enzyme is in the appropriate environment to bind single-stranded nucleic acids according to our findings. Consistent with this impoverished dNTP pool environment, it has been reported that HIV RNA immunoprecipitates with SAMHD1 in infected macrophages16. It is unclear whether this involves specificity for structural or sequence attributes of HIV nucleic acid, interactions with other binding proteins, or whether SAMHD1 nonspecifically associates with RNA when it is highly expressed and dNTP pools are low. The reported interaction with HIV RNA is somewhat enigmatic given that the preponderance of available data indicates that SAMHD1 is nuclear localized40,41. Indeed, the nuclear localization of SAMHD1 is better suited for inhibition of endogenous retroelement replication13,14. This may have relevance because one of the hallmarks of AGS is chronic interferon α production induced by dysregulated LINE element expression or continuous DNA damage2.

In addition to a potential role in viral restriction in terminally differentiated immune cells, single strand nucleic acid binding by SAMHD1 might also serve a physiological role in host nucleotide homeostasis42,43. A key question is how reversible regulation would be obtained in the presence of high concentrations of nucleic acids and dNTPs in the nucleus? Specificity for single stranded nucleic acids is expected to be facilitated by the genome architecture of mammalian cells that consists of duplex DNA compacted into the form of chromatin, which is not expected to bind SAMHD1. The transient generation of single-stranded regions of DNA (and RNA) during DNA replication or transcription, could then provide opportunities for SAMHD1 to interact with either ssDNA or RNA. Although SAMHD1 is minimally expressed in early S phase in dividing cells42, it still persists at low levels and a function for ssDNA binding can be speculated based on the model in Figure 7: upon binding to single-stranded DNA generated at origins of replication during S phase, SAMHD1’s dNTP hydrolase activity would be down regulated, leading to an increase in local dNTP pool levels required for DNA replication. Regulation by such a mechanism would involve competitive effects between the local dNTP pool and ssDNA concentrations. Although cellular mRNA is also single-stranded, and would be expected to constitutively inhibit SAMHD1, such interactions may be inhibited by RNA secondary structure, binding of other proteins that possess greater affinity than SAMHD1 or other mechanisms that make mRNA generally less accessible. All of these possibilities require further experimentation to confirm their viability.

Additional roles for SAMHD1 in cancer and DNA repair have been suggested and some of these functions indicate a potential role for nucleic acid binding44. Inactivating mutations in the SAMHD1 gene, epigenetic silencing marks, and targeted knock-out of the enzyme have been associated with increased cellular proliferation43, reduced apoptosis43, as well as B cell lymphoma and other cancers44–46. Since it is generally accepted that transformed cells show dysregulated dNTP metabolism as compared with their normal counterparts47, it is not surprising that cancer-associated mutants of SAMHD1 generally show reduced dNTPase activity in vitro46. The fact that SAMHD1 has been found to co-localize with 53bp1 at double-stranded DNA breaks suggests a further possible role in DNA repair and connection to oncogenesis44. Although the mechanism for recruitment of SAMHD1 to dsDNA breaks is unknown, the binding to resected ssDNA ends at sites of damage is one plausible mechanism. The recruitment could result from the direct binding of SAMHD1 to the damaged DNA, which could also be facilitated by additional protein-protein interactions.

Functions of the Carboxyl Terminal Tail of SAMHD1

The carboxyl terminal tail of SAMHD1 has been of significant interest since it was discovered that Thr592 was phosphorylated by cyclin dependent kinase48,49. However, the function of the tail has remained mysterious because phosphorylation or phosphomimetic mutation at this site has little effect on the in vitro dNTPase activity of the enzyme and we previously found no difference in the ssNA binding affinity of the T592E mutant17. Furthermore, removal of tail residues 582–626 in this study had no effect on nucleic acid binding and a mild effect on the dNTPase activity (Fig. 5B and Supplementary Fig. S5A). Nevertheless, the T592E mutation largely suppresses the restriction activity of SAMHD1 with only a mild effect on dNTP pool levels, possibly suggesting a function of the tail that is unrelated to dNTPase activity48–51. In this regard, our crosslinking results demonstrating proximity of ssNA with the tail are intriguing. It seems most probable that the interaction of nucleic acids with the flexible tail are transient and dynamic and therefore contribute little to the observed ssNA binding affinity, which is consistent with the weak but measureable affinities of the isolated tail with ssDNA and ssRNA (Fig. 5D). In the context of the full-length protein, it is also possible that the contribution of the tail to ssNA binding affinity is antagonized by competitive binding of the tail to the protein.

SAMHD1 is not a Polyribonucleotide Phosphorylase

Despite using the best methods available, we have not been able to experimentally link the nucleic acid binding activity of SAMHD1 with any exonuclease or polynucleotide phosphorylase activities. With respect to polyribonucletide phosphorylase activity, there are no HD domain proteins yet identified which possess this function despite the wide ranging activities of this superfamily of enzymes in biology52. Instead, PNPase activity is confined to a separate superfamily of proteins that are characterized by low Km values for the phosphate substrate (700 µM) and larger kcat values (~ 1 s−1)53. These kinetic parameters for a true PNPase are vastly superior to the previously reported PNPase activity of SAMHD119. We conclude from the studies described here and previously that SAMHD1 has no detectable exonuclease or PNPase activities.

Conclusion

The elucidation of the interfacial binding site of ssDNA and ssRNA on SAMHD1 supports the in vitro data previously obtained17, is consistent with a lack of nuclease or phosphorylase activity associated with the SAMHD1 active site17, and suggests a possible regulatory role for single-stranded nucleic acids in nucleotide homeostasis, viral infection and DNA repair processes. The model outlined here, and the nucleic acid binding-deficient mutants that have been generated, will facilitate cellular studies of the role of this activity in the context of viral restriction, dNTP pool homeostasis, and DNA repair.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01-GM056834 (J.T.S.), R01-GM103853 (N.N.B.), and T32-GM008763. K.J.S. was supported by the American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship 14PRE 20380664.

Footnotes

One supplemental table, six supplemental figures, and an appendix of annotated mass spectra. The sequences of all oligonucleotides used in this study (Table S1); a protein-stained gel showing the presence of DNA-protein crosslinked complexes (Figure S1), a representation of the crosslinked and uncrosslinked amino acids on the surface of SAMHD1 (Figure S2), BrdU crosslinking and oligomeric state determination of SAMHD1 variants (Figure S3), tryptophan fluorescence thermal melt curves of SAMHD1 variants (Figure S4), assessment of the dNTPase activity and oligomerization of Δ583–626 SAMHD1 (Figure S5), validation of the lack of ribonuclease activity from SAMHD1 using H206A/D207A SAMHD1 (Figure S6). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Rice GI, Bond J, Asipu A, Brunette RL, Manfield IW, Carr IM, Fuller JC, Jackson RM, Lamb T, Briggs TA, Ali M, Gornall H, Couthard LR, Aeby A, Attard-Montalto SP, Bertini E, Bodemer C, Brockmann K, Brueton LA, Corry PC, Desguerre I, Fazzi E, Cazorla AG, Gener B, Hamel BCJ, Heiberg A, Hunter M, van der Knaap MS, Kumar R, Lagae L, Landrieu PG, Lourenco CM, Marom D, McDermott MF, van der Merwe W, Orcesi S, Prendiville JS, Rasmussen M, Shalev SA, Soler DM, Shinawi M, Spiegel R, Tan TY, Vanderver A, Wakeling EL, Wassmer E, Whittaker E, Lebon P, Stetson DB, Bonthron DT, Crow YJ. Mutations involved in Aicardi-Goutières syndrome implicate SAMHD1 as regulator of the innate immune response. Nat Genet. 2009;41:829–832. doi: 10.1038/ng.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crow YJ, Manel N. Aicardi-Goutières syndrome and the type I interferonopathies. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:429–440. doi: 10.1038/nri3850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laguette N, Sobhian B, Casartelli N, Ringeard M, Chable-Bessia C, Ségéral E, Yatim A, Emiliani S, Schwartz O, Benkirane M. SAMHD1 is the dendritic- and myeloid-cell-specific HIV-1 restriction factor counteracted by Vpx. Nature. 2011;474:654–657. doi: 10.1038/nature10117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hrecka K, Hao C, Gierszewska M, Swanson SK, Kesik-Brodacka M, Srivastava S, Florens L, Washburn MP, Skowronski J. Vpx relieves inhibition of HIV-1 infection of macrophages mediated by the SAMHD1 protein. Nature. 2011;474:658–661. doi: 10.1038/nature10195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldstone DC, Ennis-Adeniran V, Hedden JJ, Groom HCT, Rice GI, Christodoulou E, Walker PA, Kelly G, Haire LF, Yap MW, de Carvalho LPS, Stoye JP, Crow YJ, Taylor IA, Webb M. HIV-1 restriction factor SAMHD1 is a deoxynucleoside triphosphate triphosphohydrolase. Nature. 2011;480:379–382. doi: 10.1038/nature10623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Powell RD, Holland PJ, Hollis T, Perrino FW. Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome gene and HIV-1 restriction factor SAMHD1 is a dGTP-regulated deoxynucleotide triphosphohydrolase. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:43596–43600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C111.317628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan J, Kaur S, DeLucia M, Hao C, Mehrens J, Wang C, Golczak M, Palczewski K, Gronenborn AM, Ahn J, Skowronski J. Tetramerization of SAMHD1 is required for biological activity and inhibition of HIV infection. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:10406–10417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.443796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hansen EC, Seamon KJ, Cravens SL, Stivers JT. GTP activator and dNTP substrates of HIV-1 restriction factor SAMHD1 generate a long-lived activated state. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E1843–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401706111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ji X, Wu Y, Yan J, Mehrens J, Yang H, DeLucia M, Hao C, Gronenborn AM, Skowronski J, Ahn J, Xiong Y. Mechanism of allosteric activation of SAMHD1 by dGTP. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:1304–1309. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ji X, Tang C, Zhao Q, Wang W, Xiong Y. Structural basis of cellular dNTP regulation by SAMHD1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E4305–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1412289111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lahouassa H, Daddacha W, Hofmann H, Ayinde D, Logue EC, Dragin L, Bloch N, Maudet C, Bertrand M, Gramberg T, Pancino G, Priet S, Canard B, Laguette N, Benkirane M, Transy C, Landau NR, Kim B, Margottin-Goguet F. SAMHD1 restricts the replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by depleting the intracellular pool of deoxynucleoside triphosphates. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:223–228. doi: 10.1038/ni.2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim ET, White TE, Brandariz-Nuñez A, Diaz-Griffero F, Weitzman MD. SAMHD1 restricts herpes simplex virus 1 in macrophages by limiting DNA replication. J Virol. 2013;87:12949–12956. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02291-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu S, Li J, Xu F, Mei S, Le Duff Y, Yin L, Pang X, Cen S, Jin Q, Liang C, Guo F. SAMHD1 Inhibits LINE-1 Retrotransposition by Promoting Stress Granule Formation. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005367. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao K, Du J, Han X, Goodier JL, Li P, Zhou X, Wei W, Evans SL, Li L, Zhang W, Cheung LE, Wang G, Kazazian HH, Yu X-F. Modulation of LINE-1 and Alu/SVA retrotransposition by Aicardi-Goutières syndrome-related SAMHD1. Cell Rep. 2013;4:1108–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beloglazova N, Flick R, Tchigvintsev A, Brown G, Popovic A, Nocek B, Yakunin AF. Nuclease activity of the human SAMHD1 protein implicated in the Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome and HIV-1 restriction. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:8101–8110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.431148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryoo J, Choi J, Oh C, Kim S, Seo M, Kim S-Y, Seo D, Kim J, White TE, Brandariz-Nuñez A, Diaz-Griffero F, Yun C-H, Hollenbaugh JA, Kim B, Baek D, Ahn K. The ribonuclease activity of SAMHD1 is required for HIV-1 restriction. Nat Med. 2014;20:936–941. doi: 10.1038/nm.3626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seamon KJ, Sun Z, Shlyakhtenko LS, Lyubchenko YL, Stivers JT. SAMHD1 is a single-stranded nucleic acid binding protein with no active site-associated nuclease activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:6486–6499. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goncalves A, Karayel E, Rice GI, Bennett KL, Crow YJ, Superti-Furga G, Bürckstümmer T. SAMHD1 is a nucleic-acid binding protein that is mislocalized due to aicardi-goutières syndrome-associated mutations. Hum Mutat. 2012;33:1116–1122. doi: 10.1002/humu.22087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ryoo J, Hwang S-Y, Choi J, Oh C, Ahn K. SAMHD1, the Aicardi-Goutières syndrome gene and retroviral restriction factor, is a phosphorolytic ribonuclease rather than a hydrolytic ribonuclease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;477:977–981. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin SY, Riggs AD. Photochemical attachment of lac repressor to bromodeoxyuridine-substituted lac operator by ultraviolet radiation. PNAS. 1974;71:947–951. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.3.947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stensballe A, Andersen S, Jensen ON. Characterization of phosphoproteins from electrophoretic gels by nanoscale Fe(III) affinity chromatography with off-line mass spectrometry analysis. Proteomics. 2001;1:207–222. doi: 10.1002/1615-9861(200102)1:2<207::AID-PROT207>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Meth. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dietz TM, Koch TH. Photochemical coupling of 5-bromouracil to tryptophan, tyrosine and histidine, peptide-like derivatives in aqueous fluid solution. Photochem. Photobiol. 1987;46:971–978. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1987.tb04879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andersson L, Porath J. Isolation of phosphoproteins by immobilized metal (Fe3+) affinity chromatography. Anal Biochem. 1986;154:250–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(86)90523-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brandariz-Nuñez A, Valle-Casuso JC, White TE, Nguyen L, Bhattacharya A, Wang Z, Demeler B, Amie S, Knowlton C, Kim B, Ivanov DN, Diaz-Griffero F. Contribution of oligomerization to the anti-HIV-1 properties of SAMHD1. Retrovirology. 2013;10:131. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-10-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holmes KC. Protein-RNA interactions during TMV assembly. J. Supramol. Struct. 1979;12:305–320. doi: 10.1002/jss.400120304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Welbourn S, Strebel K. Low dNTP levels are necessary but may not be sufficient for lentiviral restriction by SAMHD1. Virology. 2016;488:271–277. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kohn G, Delvaux D, Lakaye B, Servais A-C, Scholer G, Fillet M, Elias B, Derochette J-M, Crommen J, Wins P, Bettendorff L. High inorganic triphosphatase activities in bacteria and mammalian cells: identification of the enzymes involved. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e43879. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seamon KJ, Hansen EC, Kadina AP, Kashemirov BA, McKenna CE, Bumpus NN, Stivers JT. Small Molecule Inhibition of SAMHD1 dNTPase by Tetramer Destabilization. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:9822–9825. doi: 10.1021/ja5035717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gallois-Montbrun S, Kramer B, Swanson CM, Byers H, Lynham S, Ward M, Malim MH. Antiviral protein APOBEC3G localizes to ribonucleoprotein complexes found in P bodies and stress granules. J Virol. 2007;81:2165–2178. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02287-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iwatani Y, Chan DSB, Wang F, Maynard KS, Sugiura W, Gronenborn AM, Rouzina I, Williams MC, Musier-Forsyth K, Levin JG. Deaminase-independent inhibition of HIV-1 reverse transcription by APOBEC3G. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:7096–7108. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adolph MB, Webb J, Chelico L. Retroviral restriction factor APOBEC3G delays the initiation of DNA synthesis by HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e64196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chaurasiya KR, McCauley MJ, Wang W, Qualley DF, Wu T, Kitamura S, Geertsema H, Chan DSB, Hertz A, Iwatani Y, Levin JG, Musier-Forsyth K, Rouzina I, Williams MC. Oligomerization transforms human APOBEC3G from an efficient enzyme to a slowly dissociating nucleic acid-binding protein. Nature Chem. 2014;6:28–33. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seto D, Bhatnagar SK, Bessman MJ. The purification and properties of deoxyguanosine triphosphate triphosphohydrolase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:1494–1499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singh D, Gawel D, Itsko M, Hochkoeppler A, Krahn JM, London RE, Schaaper RM. Structure of Escherichia coli dGTP triphosphohydrolase: a hexameric enzyme with DNA effector molecules. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:10418–10429. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.636936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tüngler V, Staroske W, Kind B, Dobrick M, Kretschmer S, Schmidt F, Krug C, Lorenz M, Chara O, Schwille P, Lee-Kirsch MA. Single-stranded nucleic acids promote SAMHD1 complex formation. J. Mol. Med. 2013;91:759–770. doi: 10.1007/s00109-013-0995-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gavegnano C, Kennedy EM, Kim B, Schinazi RF. The Impact of Macrophage Nucleotide Pools on HIV-1 Reverse Transcription, Viral Replication, and the Development of Novel Antiviral Agents. Mol Biol Int. 2012;2012:625983–8. doi: 10.1155/2012/625983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hansen EC, Ransom M, Hesselberth JR, Hosmane NN, Capoferri AA, Bruner KM, Pollack RA, Zhang H, Drummond MB, Siliciano JM, Siliciano R, Stivers JT. Diverse fates of uracilated HIV-1 DNA during infection of myeloid lineage cells. Elife. 2016;5:37333. doi: 10.7554/eLife.18447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baldauf H-M, Pan X, Erikson E, Schmidt S, Daddacha W, Burggraf M, Schenkova K, Ambiel I, Wabnitz G, Gramberg T, Panitz S, Flory E, Landau NR, Sertel S, Rutsch F, Lasitschka F, Kim B, König R, Fackler OT, Keppler OT. SAMHD1 restricts HIV-1 infection in resting CD4(+) T cells. Nat Med. 2012;18:1682–1687. doi: 10.1038/nm.2964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schaller T, Pollpeter D, Apolonia L, Goujon C, Malim MH. Nuclear import of SAMHD1 is mediated by a classical karyopherin a/ 1 dependent pathway and confers sensitivity to VpxMAC induced ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. Retrovirology. 2014;11:1–16. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-11-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Franzolin E, Pontarin G, Rampazzo C, Miazzi C, Ferraro P, Palumbo E, Reichard P, Bianchi V. The deoxynucleotide triphosphohydrolase SAMHD1 is a major regulator of DNA precursor pools in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:14272–14277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312033110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bonifati S, Daly MB, St Gelais C, Kim SH, Hollenbaugh JA, Shepard C, Kennedy EM, Kim D-H, Schinazi RF, Kim B, Wu L. SAMHD1 controls cell cycle status, apoptosis and HIV-1 infection in monocytic THP-1 cells. Virology. 2016;495:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clifford R, Louis T, Robbe P, Ackroyd S, Burns A, Timbs AT, Wright Colopy G, Dreau H, Sigaux F, Judde JG, Rotger M, Telenti A, Lin Y-L, Pasero P, Maelfait J, Titsias M, Cohen DR, Henderson SJ, Ross MT, Bentley D, Hillmen P, Pettitt A, Rehwinkel J, Knight SJL, Taylor JC, Crow YJ, Benkirane M, Schuh A. SAMHD1 is mutated recurrently in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and is involved in response to DNA damage. Blood. 2014;123:1021–1031. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-490847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang J-L, Lu F-Z, Shen X-Y, Wu Y, Zhao L-T. SAMHD1 is down regulated in lung cancer by methylation and inhibits tumor cell proliferation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;455:229–233. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.10.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rentoft M, Lindell K, Tran P, Chabes AL, Buckland RJ, Watt DL, Marjavaara L, Nilsson AK, Melin B, Trygg J, Johansson E, Chabes A. Heterozygous colon cancer-associated mutations of SAMHD1 have functional significance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:4723–4728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1519128113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gandhi VV, Samuels DC. A review comparing deoxyribonucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) concentrations in the mitochondrial and cytoplasmic compartments of normal and transformed cells. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2011;30:317–339. doi: 10.1080/15257770.2011.586955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cribier A, Descours B, Valadão ALC, Laguette N, Benkirane M. Phosphorylation of SAMHD1 by cyclin A2/CDK1 regulates its restriction activity toward HIV-1. Cell Rep. 2013;3:1036–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.White TE, Brandariz-Nuñez A, Valle-Casuso JC, Amie S, Nguyen LA, Kim B, Tuzova M, Diaz-Griffero F. The retroviral restriction ability of SAMHD1, but not its deoxynucleotide triphosphohydrolase activity, is regulated by phosphorylation. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:441–451. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tang C, Ji X, Wu L, Xiong Y. Impaired dNTPase Activity of SAMHD1 by Phosphomimetic Mutation of T592. J Biol Chem. 2015;290 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.677435. jbc.M115.677435–26359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arnold LH, Groom HCT, Kunzelmann S, Schwefel D, Caswell SJ, Ordonez P, Mann MC, Rueschenbaum S, Goldstone DC, Pennell S, Howell SA, Stoye JP, Webb M, Taylor IA, Bishop KN. Phospho-dependent Regulation of SAMHD1 Oligomerisation Couples Catalysis and Restriction. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1005194. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aravind L, Koonin EV. The HD domain defines a new superfamily of metal-dependent phosphohydrolases. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23:469–472. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01293-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Godefroy T, Cohn M, Grunberg-Manago M. Kinetics of polymerization and phosphorolysis reactions of E. coli polynucleotide phosphorylase. Role of oligonucleotides in polymerization. Eur. J. Biochem. 1970;12:236–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1970.tb00843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Portnoy V, Palnizky G, Yehudai-Resheff S, Glaser F, Schuster G. Analysis of the human polynucleotide phosphorylase (PNPase) reveals differences in RNA binding and response to phosphate compared to its bacterial and chloroplast counterparts. RNA. 2008;14:297–309. doi: 10.1261/rna.698108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.