Abstract

Background and Objectives

There is evidence that anxiety sensitivity (AS) plays a role in the maintenance of smoking, yet there is little understanding of how AS interplays with other affective symptomatology variables that are also related to smoking, such as dysphoria. Therefore, the current cross-sectional study evaluated the interactive effects of AS and dysphoria on emotion regulatory cognitions, including smoking negative affect reduction expectancies, perceived barriers for cessation, and smoking-specific experiential avoidance.

Method

A total of 448 adult treatment-seeking daily smokers, who responded to study advertisements, were recruited to participate in a smoking cessation treatment trial (47.8% female; Mage = 37.2, SD =13.5). The current study utilized self-report baseline data from trial participants.

Results

After accounting for covariates, simple slope analyses revealed that AS was positively related to negative affect reduction expectancies (β = .03, p =.01), perceived barriers to cessation (β =.22, p = .002), and smoking avoidance and inflexibility (β =.07, p = .04), among smokers with lower (versus higher) levels of dysphoria.

Conclusions

The current findings suggest that higher levels of dysphoria may mitigate the relation between AS and emotion regulatory cognitions of smoking.

Scientific Significance

The current findings highlight the unique and additive clinical relevance of AS and dysphoria regarding emotion regulatory smoking cognitions that may impede quit success.

Keywords: Anxiety Sensitivity, Dysphoria, Smoking, Emotion Regulation

Background and Objectives

Cigarette smoking co-occurs with psychiatric disorders at an exceedingly higher rate than among individuals without mental illness.1 Specifically, depressive and anxiety syndromes –commonly referred to as emotional disorders – are among the disorders that are frequently comorbid with smoking.2 The co-occurrence of these emotional disorders and smoking significantly increases the risk of smoking cessation failure,3 heightens severity of tobacco withdrawal,4 and contributes to maladaptive cognitive beliefs and cognitive-affective reactions to tobacco use.5 However, the underlying mechanisms linking emotional symptomatology and smoking are not well understood.

One means of elucidating the mechanisms linking emotional symptomatology and smoking is to investigate the role of transdiagnostic emotional vulnerability factors.6 Anxiety sensitivity (AS), or the tendency to fear anxiety-related sensations,7 is a transdiagnostic construct involved in the etiology and maintenance of anxiety disorders (e.g., panic and social anxiety) and other emotional disorders (e.g., depression and PTSD).8 AS also statistically accounts for the relation of emotional disorders with tobacco dependence, perceived barriers to cessation, and severity of problematic symptoms while quitting.9 Additionally, high AS is related to greater odds of early smoking lapse10 and relapse.11

While it is clear that AS plays a role in the maintenance of smoking, there is little understanding of how AS interplays with others affective symptomatology variables that are also related to smoking. One such consideration is the interplay of AS and dysphoria. Dysphoria—a symptom cluster of depression that is characterized by anhedonia, sadness, psychomotor disturbance, worthlessness, worry, and cognitive difficulty12—is associated with numerous aspects of smoking behavior, including greater levels of dependence, smoking rate, and negative affect reduction smoking motives,13 as well as perceived barriers to cessation,14 and smoking-specific experiential avoidance.14

Dysphoria is generally related to depressed affect and highly correlated with specific dimensions of depressed affect, such as anhedonia—another core dimension of depression.15. Indeed, in a sample of smokers who had successfully quit following smoking cessation treatment, participants characterized by high levels of AS, who also endorsed greater anhedonic symptoms, reported more severe nicotine withdrawal symptoms of restlessness and frustration across the first two weeks of their quit attempt.16 The primary aim of the current investigation is to further extend past work by examining the interaction of AS with dysphoric symptoms as it relates more broadly to additional smoking processes. Consistent with previous work, we theorize that AS may interact with dysphoria to significantly increase emotion regulatory smoking cognitions, including smoking negative affect reduction expectancies, perceived barriers for cessation, and smoking-specific experiential avoidance. Indeed, an interaction between AS and dysphoria may produce a synergetic effect to exacerbate maladaptive cognitions for the emotion regulatory properties of smoking. For example, an individual high in AS is likely to fear the negative consequences of aversive stimuli17 and cope with the corresponding emotional distress through escape/avoidance-oriented tactics,18 such as smoking. Similarly, smokers high in dysphoria may be more prone to relieve negative affective symptoms by smoking.19 Therefore, smokers higher in AS who also have higher co-occurring levels of dysphoria may be more prone to utilize smoking as a means to regulate their negative affect symptoms, hold stronger beliefs about difficulties in quitting, and have a greater desire to quit because they are apt to be cognitively and affectively reactive to aversive emotional states.6

Together, the present investigation examined the interactive effects of AS and dysphoria on smoking negative affect reduction expectancies, perceived barriers for cessation, and smoking-specific experiential avoidance. It was hypothesized that AS and dysphoria would demonstrate a significant interaction, such that the strength of the relation between AS symptoms and emotion regulatory cognitions of smoking would vary depending on the level of dysphoria. Based on prior research, higher levels of AS and co-occurring dysphoric symptoms were expected to be associated with greater emotion regulatory cognitions of smoking.

Method

Participants

Participants included 448 adult smokers (47.8% female; Mage = 37.2, SD =13.5) who responded to study advertisements (e.g., flyers, newspaper ads, radio announcements). In terms of ethnic background, 85.7% of participants identified as Caucasian, 8.3% identified as African-American, 2.5% identified as Hispanic, 0.9% identified as Asian, and 2.5% identified as “other.” Participants reported smoking an average of 16.6 cigarettes per day (SD = 9.9), smoking their first cigarette at 14.8 years of age (SD = 3.4), and initiating regular (daily) smoking at 17.4 years of age (SD = 3.7). The average score on the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence20 was 5.1 (SD =2.3), indicating moderate levels of tobacco dependence.

As determined by the baseline Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders-Non-Patient Version (SCID-I/NP21), 45.0% of the sample met criteria for current (past year) Axis I psychopathology. Among participants with current psychopathology, the average number of diagnoses per participant was 1.4 (SD = .49).

Participants were excluded based on the following criteria: (1) past month use of pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation; (2) limited mental competency and inability to provide informed, voluntary, written consent; (3) endorsement of current or past psychotic-spectrum symptoms via structured interview screening; and (4) current suicidal risk so severe as to warrant immediate treatment.

Predictor Variables

Anxiety Sensitivity Index-III (ASI-3).22

The ASI-3 is an 18-item self-report measure, based in part upon the original Anxiety Sensitivity Index (ASI),11 of the sensitivity to, and fear of the potential negative consequences of anxiety-related symptoms and sensations. Respondents are asked to indicate, on a 5-point Likert-type scale (0 = "very little" to 4 = "very much"), the degree to which they are concerned about these possible negative consequences. In the present study, we utilized the total ASI-3 score (Cronbach's alpha = .90).

Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (IDAS)12 Dysphoria subscale

The IDAS is a 64-item self-report instrument that assesses distinct affect symptom dimensions within the past two weeks. Items are answered on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all” to “extremely.” The IDAS subscales show strong internal consistency, convergent and discriminant validity with psychiatric diagnoses and self-report measures, and short-term retest reliability (r = 0.79) with both community and psychiatric patient samples.12 In the present study, we employed the 10-item dysphoria subscale (e.g., ‘‘I felt depressed;’’ Cronbach’s alpha = .92).

Criterion Variables

Smoking Consequences Questionnaire (SCQ).23

The SCQ is a 50-item self-report measure on which respondents indicate, on a 10-point Likert-type scale (0 = completely unlikely to 10 = completely likely), an individual’s expectancies about cigarette smoking. The SCQ includes four subscales: positive reinforcement (15 items; e.g., “I enjoy the taste sensations while smoking”), negative reinforcement/negative affect reduction (12 items; e.g., “Smoking helps me calm down when I feel nervous”), negative consequences (18 items; e.g., “The more I smoke, the more I risk my health”), and appetite control (5 items; e.g., Smoking helps me control my weight”). The SCQ and its constituent factors have excellent psychometric properties.23 Extant research provides evidence for unique clinical utility of the SCQ-NR subscale. Indeed, the SCQ-NR incrementally relates to psychological vulnerabilities that may contribute to problematic smoking and greater quit difficulty beyond the other SCQ subscales.24 Therefore, we elected to focus solely on the SCQ-NR in the current study (Cronbach alpha =.87).

Barriers to Cessation Scale (BCS).25

The BCS assessed perceived barriers, or specific stressors, associated with smoking cessation (e.g., ‘Having strong feelings such as anger, or feeling upset when you are with other people’). The BCS is a 19-item measure on which respondents indicate, on a 4-point Likert-style scale (0 = “not a barrier” to 3 = “large barrier”), the extent to which they identify with each of the identified perceived barriers to cessation. Researchers report good internal consistency regarding the total score, and good content and predictive validity of the measure.25 The total score was utilized and this scale demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.88).

Avoidance and Inflexibility Scale (AIS).26

The AIS is a 13-item self-reported measure of smoking-specific experiential avoidance. Respondents rate how they respond to difficult thoughts that encourage smoking (e.g., “I need a cigarette”), difficult feelings that encourage smoking (e.g., stress, fatigue, boredom), and bodily sensations that encourage smoking (e.g., “physical cravings or withdrawal symptoms”). Example items include “How likely is it you will smoke in response to [thoughts/feelings/sensations]?” and “How important is getting rid of [thoughts/feelings/sensations]?” Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all to 5 = Very much), with higher scores reflecting greater levels of smoking-specific experiential avoidance (possible range 13–65). The AIS has displayed good reliability and validity in past work.27 In the present study, the AIS total score was used (Cronbach’s α = .92).

Descriptive Variables and Covariates

Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND).20

This instrument is a well-established six-item scale designed to assess gradations in tobacco dependence. This measure exhibits good internal consistency, high degrees of test-retest reliability,28 and positive relations with key smoking variables (e.g., salivary cotinine20). The FTND demonstrated typical-range internal consistency among the present study sample (Cronbach's alpha = .60). The FTND was used to describe overall levels of nicotine dependence within the current sample.

Smoking History Questionnaire (SHQ).29

The SHQ is a self-report questionnaire used to assess smoking history and pattern (e.g. smoking rate, age of onset of initiation). It has been successfully used in previous studies as a measure of smoking history.30 The present study utilized the following variables from the SHQ: average number of cigarettes smoked per day during the last week (smoking rate), age of onset of first cigarette, and age at onset of regular (daily) cigarette smoking.

Demographics Questionnaire

Demographic data used for descriptive purposes included gender, age, and race. Gender was also used as a covariate in all analyses.

Structured Clinical Interview-Non-Patient Version for DSM-IV (SCID-N/P).21

Diagnostic assessments were performed using the SCID-N/P. The interviews were administered by a trained staff member and supervised by independent doctoral-level psychologists. All interviews were audio-taped and the reliability of a random selection of approximately 12.5% of interviews were checked (MJZ) for accuracy; no cases of diagnostic coding disagreement were noted. Two variables were derived from the SCID interviews: 1) presence/absence of current Axis I disorder (0 = absent, 1 = present); and 2) presence/absence of current non-alcohol substance abuse/dependence (0 = absent, 1 = present).

Medical History Form

Current and lifetime medical illnesses and current use of prescribed medication were assessed using a medical history checklist. As in past work,14 for current and lifetime medical illnesses, a composite variable was computed for the present study as an index of tobacco-related medical illnesses, which was used as a covariate in all models. Items in which participants indicated having ever been diagnosed (respiratory disease, asthma, heart problems, and hypertension, all coded 0 = no, 1 = yes) were summed to create a total score (observed range from 0–4), with greater scores reflecting the presence of multiple markers of tobacco-related medical illnesses.

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT).31

The AUDIT is a 10-item self-report measure developed to identify individuals with problematic drinking. Its scores range from 0 to 30, with higher scores reflecting more problematic drinking. The AUDIT’s psychometric properties are well documented. In the current investigation, the AUDIT total score internal consistency was good (Cronbach’s α = .89).

The Big Five Inventory (BFI).32

This self-report measure assesses the Big Five personality traits (i.e., extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness). Participants rate a series of phrases corresponding to the adjectives considered to be markers of the five personality domains. The questionnaire has 44 items rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = disagree strongly to 5 = agree strongly) based on the degree to which the phrase applies. The present study used the neuroticism subscale of the Big Five Inventory (e.g., “is depressed, blue”) to index individuals’ tendency to experience negative mood states (Cronbach α = .89).

Procedure

Interested participants, who also met the initial requirements during a telephone screen, were scheduled to come in for a structured clinical interview to assess the presence or absence of any Axis I condition (N = 582). Individuals who were deemed eligible after the screening/interview process were then scheduled for a baseline appointment to complete various demographic, smoking, anxiety, and substance use assessments. Following written informed consent, participants were interviewed using the SCID-I/NP and completed a computerized self-report battery. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Vermont and Florida State University (clinicaltrials.gov # NCT01753141). The current study is based on secondary analyses of baseline (pre-treatment) data for a subset of the sample which was selected on the basis of complete data for all studied variables (N = 448).

Analytic Strategy

First, a series of zero-order correlations were conducted to examine associations between study variables. To test the main and interactive effects of AS and dysphoria on emotion regulatory cognitions of smoking, a Generalized Linear Modeling (GLM) in Proc GLM (SAS 9.4) was employed. Specifically, three hierarchical regression analyses were conducted. In the first step of each model, gender, tobacco-related medical illness, baseline levels of neuroticism, smoking rate, alcohol problems, SCID-based current non-alcohol substance abuse/dependence, and SCID-based current Axis 1 disorder (other than substance abuse/dependence) were entered as covariates. Next, AS and dysphoria were entered (second step). Finally, the interaction term between AS and dysphoria was entered at the third step. Continuous variables were grand mean centered. Three separate GLM models were conducted with (1) smoking negative affect reduction expectancies, (2) perceived barriers to cessation, and (3) smoking avoidance and inflexibility. Standardized beta coefficient estimates and respective significance levels within each model were reported.

Results

Descriptive data

Descriptive data and correlations of the study variables included are presented in Table 1. AS and dysphoria were positively significantly correlated with smoking negative affect reduction expectancies, perceived barriers to cessation, and smoking-specific experiential avoidance.

Table 1.

Zero-order correlations among theoretically-relevant variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | Mean (or n) |

SD (or %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender (% Female) | 1 | .27** | −.11* | −.11* | .002 | .20** | −.03 | .11* | .09 | .19** | .23** | .18** | 214 | 47.8 |

| 2. Neuroticism | 1 | .12** | −.001 | .004 | .41** | .06 | .63** | .53** | .37** | .33** | .21** | 22.84 | 6.73 | |

| 3. AUDIT | 1 | −.07 | −.10* | .09 | .15** | .22** | .19** | .15** | .07 | .03 | 6.11 | 6.00 | ||

| 4. CPD | 1 | .03 | .03 | .003 | .05 | .05 | .10* | .08 | .16** | 16.62 | 10.01 | |||

| 5. Medical Problems | 1 | .08 | −.07 | −.03 | .02 | −.10* | .01 | .05 | .37 | .62 | ||||

| 6. Axis I Disorder | 1 | .08 | .44** | .37** | .19** | .18** | .15** | 164 | 36.5 | |||||

| 7. Non-alc-abuse | 1 | .11* | .14** | .05 | .04 | −.01 | 38 | 8.5 | ||||||

| 8. Dysphoria | 1 | .61** | .39** | .41** | .31** | 18.99 | 7.56 | |||||||

| 9. AS | 1 | .27** | .31** | .24** | 14.76 | 11.97 | ||||||||

| 10. SCQnr | 1 | .51** | .46** | 5.66 | 1.79 | |||||||||

| 11. Perceived BCS | 1 | .58** | 24.93 | 11.11 | ||||||||||

| 12. AIS | 1 | 45.04 | 10.78 |

Note. N=448;

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Gender (0=male; 1=female);

Neuroticism = Big Five Inventory– Neuroticism subscale1; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test – total score2; CPD = Number of cigarettes per day during past week per the Smoking History Questionnaire3; Medical Problems = Tobacco-related medical illnesses per the Medical Screening Questionnaire; Axis I Disorder = Current Axis I disorder(other than substance abuse problems) per the Structured Clinical Interview—Non-Patient Version for DSM-IV (0=no; 1=yes)4; Non-alc-abuse = Current non-alcohol substance abuse/dependence diagnosis per the Structured Clinical Interview—Non-Patient Version for DSM-IV (0=no; 1=yes)4; Dysphoria= Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (IDAS) Dysphoria subscale5; AS= Anxiety Sensitivity Index-III – total score6; SCQnr,= The negative affect reduction subscale of Smoking Consequences Questionnaire7; BCS= Barriers to Cessation Scale8; AIS= Avoidance and Inflexibility Scale.9

GLM analyses

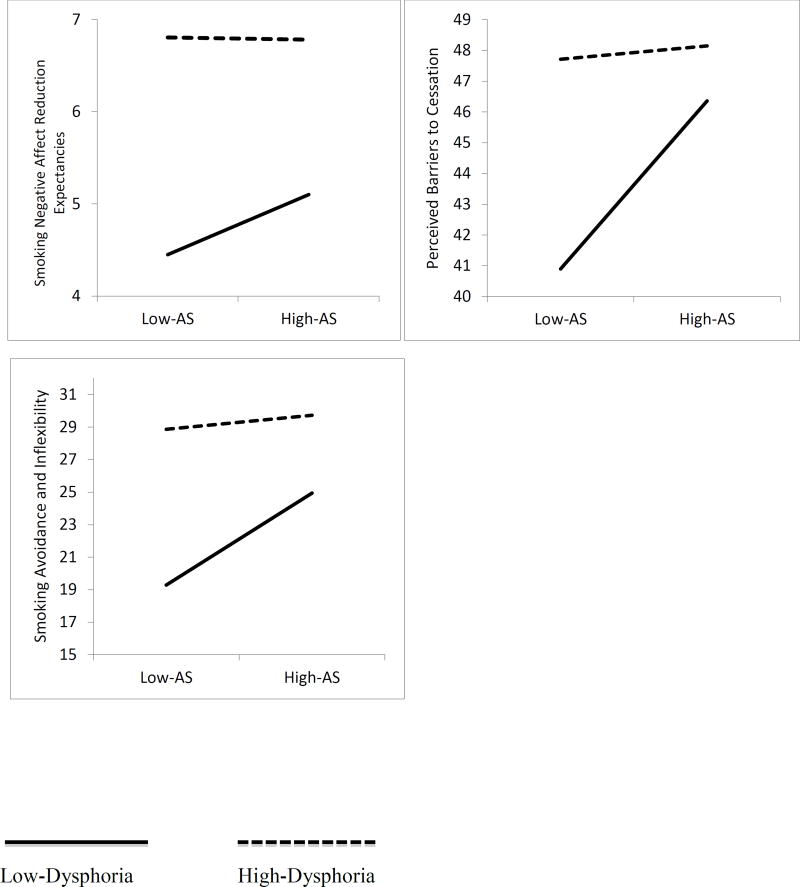

In terms of negative affect reduction expectancies, covariates entered at the first step accounted for a significant amount of variance (R2 = .19, F(7, 441) = 15.6, p <.001); gender, tobacco-related medical illness, neuroticism, smoking rate, and alcohol problems were significant predictors (β = 0.13, p = 0.005; β = .31, p <.001, β = 0.12, p = .007; β = 0.12, p = 0.003; β = 0.03, p = 0.02, respectively). At step two, only dysphoria was a significant predictor (β = .23, p < .001). At the third step, the interaction was significant (β = −.34, p = 0.03; Table 2). Simple slope analyses revealed that AS was positively related to negative affect reduction expectancies among smokers with lower (versus higher) levels of dysphoria (β = .03, p = .01). See Figure 1.

Table 2.

Main and Interactive Effects of anxiety sensitivity and dysphoria for the criterion variables.

| Smoking Negative Affect Reduction Expectancies | ||||

|

| ||||

| β | T | p | R2 Change | |

| Step 1 | ||||

| Gender | .13 | 2.82 | .005 | |

| Neuroticism | .31 | 6.42 | <.001 | |

| AUDIT | .12 | 2.72 | .007 | |

| CPD | .12 | 2.98 | .003 | |

| Medical Problems | −.10 | −2.35 | .02 | |

| Axis I Disorder | .03 | .71 | .47 | .19*** |

| Non-alc-abuse | .00 | .17 | .85 | |

| Step 2 | ||||

| Dysphoria | .23 | 3.78 | <.001 | |

| AS | .01 | .16 | .86 | .03*** |

| Step 3 | ||||

| Dysphoria * AS | −.34 | −2.11 | .03 | <.01* |

|

| ||||

| Perceived Barriers to Cessation | ||||

|

| ||||

| β | t | p | R2 Change | |

| Step 1 | ||||

| Gender | .17 | 3.81 | <.001 | |

| Neuroticism | .26 | 5.40 | <.001 | |

| AUDIT | .06 | 1.42 | .15 | |

| CPD | .10 | 2.33 | .02 | |

| Medical Problems | .01 | .14 | .88 | |

| Axis I Disorder | .02 | .53 | .59 | .14*** |

| Non-alc-abuse | .02 | .41 | .67 | |

| Step 2 | ||||

| Dysphoria | .33 | 5.45 | <.001 | |

| AS | .07 | 1.29 | .19 | .08*** |

| Step 3 | ||||

| Dysphoria * AS | −.42 | −2.64 | .01 | .01** |

|

| ||||

| Smoking-specific Experiential Avoidance | ||||

|

| ||||

| β | t | p | R2 Change | |

| Step 1 | ||||

| Gender | .15 | 3.18 | .002 | |

| Neuroticism | .14 | 2.87 | .004 | |

| AUDIT | .05 | 1.09 | .27 | |

| CPD | .17 | 3.89 | <.001 | |

| Medical Problems | .05 | 1.13 | .25 | |

| Axis I Disorder | .05 | 1.00 | .31 | .10*** |

| Non-alc-abuse | .03 | .71 | .47 | |

| Step 2 | ||||

| Dysphoria | .28 | 4.37 | <.001 | |

| AS | .08 | 1.45 | .14 | .06*** |

| Step 3 | ||||

| Dysphoria * AS | −.35 | −2.11 | .03 | .01* |

Note. N=448;

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Gender (0=male; 1=female);

Neuroticism = Big Five Inventory– Neuroticism subscale1; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test – total score2; CPD = Number of cigarettes per day during past week per the Smoking History Questionnaire3; Medical Problems = Tobacco-related medical illnesses per the Medical Screening Questionnaire; Axis I Disorder = Current Axis I disorder (other than substance abuse problems) per the Structured Clinical Interview—Non-Patient Version for DSM-IV (0=no; 1=yes)4; Non-alc-abuse = Current non-alcohol substance abuse/dependence diagnosis per the Structured Clinical Interview—Non-Patient Version for DSM-IV (0=no; 1=yes)4; Dysphoria= Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (IDAS) Dysphoria subscale5; AS= Anxiety Sensitivity Index-III – total score.6

Figure 1.

Plotting the interactive effects of dysphoria and anxiety sensitivity for dependent variables.

In terms of perceived barriers to cessation, covariates entered at the first step accounted for a significant amount of variance (R2 = .18, F (7, 441) = 14.4, p < .001); gender, neuroticism, and smoking rate were significant predictors (β = .17, p < .001; β = 0.26, p < .001, β = 0.10, p = 0.02, respectively). Only dysphoria accounted for a significant amount of variance at the second step (β = .49, p < .001). At the third step, the interaction term for dysphoria and AS also was significant (β = −.42, p = .01; Table 2). Simple slope analyses revealed that AS was positively related to perceived barriers to cessation among individuals with lower (versus higher) levels of dysphoria (β =.22, p = .002). See Figure 1.

In terms of smoking avoidance and inflexibility, covariates entered at the first step of the hierarchical regression accounted for a significant amount of variance (R2 = .04, F(7, 441) = 2.9, p < .001); gender, neuroticism, and smoking rate were significant predictors (β =.15, p = .002, β =.14, p =.004, β =.17, p < .001, respectively). Dysphoria accounted for a significant amount of variance at the second step (β = .28, p < .001). At the third step, the interaction term for smoking rate was significant (β = −.35, p = 0.03; Table 2). Simple slope analyses revealed that AS was positively related to smoking avoidance and inflexibility among individuals with lower (versus higher) levels of dysphoria (β =.07, p = .04). See Figure 1.

Conclusions

Results indicated a significant interaction between AS and dysphoria in regard to the studied smoking emotion regulatory cognitions; however, the form of the interaction was different than what we predicted. Namely, the association between AS and the studied emotion regulatory cognitions of smoking were positive across levels of AS for those with lower dysphoria, but not higher dysphoria. The observed effects were evident after accounting for gender, tobacco-related medical illness, neuroticism, smoking rate, alcohol consumption, current non-alcohol substance abuse/dependence, and current Axis I disorders and consistent across all three smoking emotion regulatory cognitions examined in this study.

The current findings suggest that higher levels of dysphoria may mitigate the relation between AS and emotion regulatory cognitions of smoking. Specifically, across each emotion regulatory cognition, smokers with higher levels of dysphoria endorsed the highest smoking use for negative affect reduction properties, perceived barriers to cessation, and smoking-specific experiential avoidance across both low and high AS levels. While AS was positively associated with the outcomes among low-dysphoria smokers, emotion regulatory cognitions about smoking did not differ across lower and higher AS for smokers with higher dysphoria. It is possible that when dysphoria is higher, smokers may experience emotional inertia that is often associated with depressive symptoms,33 and therefore, the role of AS on emotion regulatory cognitions is blunted. That is, dysphoria may be such a potent precipitant of negative thoughts about quitting, beliefs that smoking reduces negative affect, and the tendency to respond to negative thoughts with quitting, that concomitant AS does not further impact these cognitive processes. Indeed, inspection of the parameter estimates for the magnitude of association with outcomes in the model including both AS and dysphoria (but excluding the interaction) show much greater effect sizes for dysphoria than AS, which was a non-significant correlate in these models. At lower levels of dysphoria, however, this same pattern is not evident and the subtle risk that AS carries for such maladaptive smoking-related emotional cognition may be expressed. These data collectively highlight that emotion risk candidates interplay in complex ways in relation to emotion regulatory cognitions of smoking.

Although not a primary aim of the investigation, it is noteworthy that AS and dysphoria were related, but distinct constructs. Indeed, these constructs shared approximately 37% of variance. This finding suggests that these two constructs, although they may overlap, are distinct and should be considered individually in empirical work.

The current findings suggest there is apt clinical utility in addressing dysphoria and AS in order to change emotion regulatory cognitions of smoking. For example, smokers with elevations in dysphoria may require targeted strategies to improve their symptoms in order to change emotion regulatory cognitions of smoking and behavior. Likewise, addressing AS, even when dysphoria symptoms are low, may facilitate improved emotion regulatory cognitions of smoking. There are numerous therapeutic tactics to address these emotion regulatory cognitions in smoking cessation programming, including but not limited to, behavioral activation,34 AS reduction,35 and exercise enhancement.36 Future work may benefit from exploring how these therapeutic tactics can change dysphoria and AS in combination to improve emotion regulatory cognitions of smoking, such as motives for smoking, withdrawal symptoms during quitting, quit attempts, and self-efficacy for quitting, and facilitate improvements in reducing smoking behavior. Examining these relations in the context of a treatment outcome study would provide novel insight for the directionality and stability of these relations.

There are a number of study caveats. First, given the cross-sectional nature of these data, the directionality of the observed effects are not known. It is possible that heightened AS exacerbates dysphoric symptoms over time. To illustrate, it may be that heightened AS may diminish over time in the presence of intensified dysphoric symptoms that result from heightened AS. Subsequently, dysphoric symptom severity may become the principal vulnerability factor impacting smoking-specific emotion regulatory cognitions. Future work could focus on the impact of AS on dysphoric symptoms over time to further disentangle their relations and impact on one another. Second, our sample consisted of community-recruited, treatment-seeking daily cigarette smokers with moderate levels of tobacco dependence. Third, the sample was largely comprised of a relatively homogenous group of treatment-seeking smokers, and therefore, it will be important for future studies to recruit a more ethnically/racially diverse sample of smokers. Lastly, this study is based on secondary analyses of baseline data for a subset of the sample, which should be considered when interpreting the results.

Overall, the present study serves as an initial investigation into the interplay between AS and dysphoria in relation to emotion regulatory smoking cognitions. Future work is needed to explore the extent to which the interactive effects of AS and dysphoria relate to other smoking processes and quit behavior (e.g., cessation outcome).

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by National Institute of Mental Health Grant (RO1-MH076629-01A1) awarded to Michael J. Zvolensky at the University of Houston, Houston, TX, and Norman B. Schmidt at Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

References

- 1.Ziedonis D, Hitsman B, Beckham JC, et al. Tobacco use and cessation in psychiatric disorders: National Institute of Mental Health report. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10(12):1691–1715. doi: 10.1080/14622200802443569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant BF, Hasin DS, Chou SP, Stinson FS, Dawson DA. Nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders in the United States: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61(11):1107–1115. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piper ME, Cook JW, Schlam TR, Jorenby DE, Baker TB. Anxiety diagnoses in smokers seeking cessation treatment: Relations with tobacco dependence, withdrawal, outcome and response to treatment. Addiction. 2011;106(2):418–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03173.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piper ME, Smith SS, Schlam TR, et al. Psychiatric disorders in smokers seeking treatment for tobacco dependence: Relations with tobacco dependence and cessation. Journal Of Consulting And Clinical Psychology. 2010;78(1):13. doi: 10.1037/a0018065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vujanovic AA, Marshall EC, Gibson LE, Zvolensky MJ. Cognitive–affective characteristics of smokers with and without posttraumatic stress disorder and panic psychopathology. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(5):419–425. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leventhal AM, Zvolensky MJ. Anxiety, depression, and cigarette smoking: A transdiagnostic vulnerability framework to understanding emotion-smoking comorbidity. Psychological Bulletin. 2015 doi: 10.1037/bul0000003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reiss S, McNally RJ. Expectancy model of fear-Theoretical issues in behavior therapy (pp. 107–121) In: Reiss S, Bootsin RR, editors. Theoretical issues in behavior therapy. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1985. pp. 107–121. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt NB, Zvolensky MJ, Maner JK. Anxiety sensitivity: Prospective prediction of panic attacks and Axis I pathology. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2006;40(8):691–699. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zvolensky MJ, Farris SG, Leventhal AM, Schmidt NB. Anxiety sensitivity mediates relations between emotional disorders and smoking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28(3):912. doi: 10.1037/a0037450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown RA, Kahler CW, Zvolensky MJ, Lejuez CW, Ramsey SE. Anxiety sensitivity: Relationship to negative affect smoking and smoking cessation in smokers with past major depressive disorder. Addictive Behaviors. 2001;26(6):887–899. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reiss S, Peterson RA, Gursky DM, McNally RJ. Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency and the prediction of fearfulness. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1986;24:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(86)90143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watson D, O'Hara MW, Kotov R, et al. Development and validation of the Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (IDAS) Psychological Assessment. 2007;19(3):253–268. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leventhal AM, Zvolensky MJ, Schmidt NB. Smoking-related correlates of depressive symptom dimensions in treatment-seeking smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2011;13(8):668–676. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buckner JD, Farris SG, Zvolensky MJ, et al. Dysphoria and smoking among treatment seeking smokers: the role of smoking-related inflexibility/avoidance. American Journal Of Drug & Alcohol Abuse. 2015;41(1):45–51. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2014.927472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Covinsky KE, Cenzer IS, Yaffe K, O'Brien S, Blazer DG. Dysphoria and anhedonia as risk factors for disability or death in older persons: implications for the assessment of geriatric depression. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2014 Jun;22(6):606–613. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langdon KJ, Leventhal AM, Stewart S, Rosenfield D, Steeves D, Zvolensky MJ. Anhedonia and anxiety sensitivity: Prospective relationships to nicotine withdrawal symptoms during smoking cessation. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2013;74(3):469. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McNally RJ. Anxiety sensitivity and panic disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;52(10):938–946. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01475-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zvolensky MJ, Forsyth JP. Anxiety sensitivity dimensions in the prediction of body vigilance and emotional avoidance. Cognitive Therapy & Research. 2002;26(4):449. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hughes JR, Gust SW, Skoog K, Keenan RM, Fenwick JW. Symptoms of tobacco withdrawal: A replication and extension. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;48(1):52–59. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810250054007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström K-O. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: A revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction to Alcohol and Other Drugs. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorders, research version, non-patient edition (SCIDI/NP) New York, NY: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor S, Zvolensky MJ, Cox BJ, et al. Robust dimensions of anxiety sensitivity: Development and initial validation of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index-3. Psychological Assessment. 2007;19(2):176–188. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brandon TH, Baker TB. The Smoking Consequences Questionnaire: The subjective expected utility of smoking in college students. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;3(3):484–491. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson KA, Zvolensky MJ, Marshall EC, Gonzalez A, Abrams K, Vujanovic AA. Linkages between cigarette smoking outcome expectancies and negative emotional vulnerability. Addict Behav. 2008 Nov;33(11):1416–1424. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macnee CL, Talsma A. Development and testing of the barriers to cessation scale. Nursing Research. 1995;44(4):214–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gifford EV, Kohlenberg BK, Hayes SC, Antonuccio DO, Piasecki MP, Palm K. Association for Advancement of Behavior Therapy. Reno, NV: Nov, 2002. Combining Bupropion SR with acceptance based behavioral therapy for smoking cessation. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farris SG, Zvolensky MJ, DiBello AM, Schmidt NB. Validation of the Avoidance and Inflexibility Scale (AIS) among treatment-seeking smokers. Psychological Assessment. 2015;27(2):467–477. doi: 10.1037/pas0000059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pomerleau CS, Carton SM, Lutzke ML, Flessland KA, Pomerleau OF. Reliability of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire and the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence. Addictive Behaviors. 1994;191(1):33–39. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)90049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Strong DR. Distress tolerance and duration of past smoking cessation attempts. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002 Feb;111(1):180–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zvolensky MJ, Lejuez C, Kahler CW, Brown RA. Nonclinical panic attack history and smoking cessation: An initial examination. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29(4):825–830. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, De La Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption--II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.John OP, Srivastava S. The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In: Pervin LA, John OP, editors. Handbook of personality: Theory and research. 2. New York: Guilford; 1999. pp. 102–138. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brose A, Schmiedek F, Koval P, Kuppens P. Emotional inertia contributes to depressive symptoms beyond perseverative thinking. Cognition & Emotion. 2015;29(3):527–538. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2014.916252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.MacPherson L, Tull MT, Matusiewicz AK, et al. Randomized controlled trial of behavioral activation smoking cessation treatment for smokers with elevated depressive symptoms. Journal Of Consulting And Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:55–61. doi: 10.1037/a0017939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zvolensky MJ, Bogiaizian D, Salazar PL, Farris SG, Bakhshaie J. An anxiety sensitivity reduction smoking cessation program for Spanish-speaking smokers. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2014;21:350–363. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smits JAJ, Zvolensky MJ, Davis ML, et al. The efficacy of vigorous-intensity exercise as an aid to smoking cessation in adults with high anxiety sensitivity: A randomized controlled trial. Psychosomatic Medicine. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000264. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]