Abstract

Introduction

Optimal treatment of inflammatory bowel disease requires specialized health care. Patients frequently travel long distances to obtain care for inflammatory bowel disease, which may hinder regular care and affect outcomes adversely.

Methods

This study included patients with established CD or UC receiving care at a single referral center between January 2005 and August 2016. Distance to our healthcare center from the zip code of residence was determined for each patient and classified into quartiles. Our primary outcome was need for IBD-related surgery with secondary outcomes being need for biologic and immunomodulator therapy. Logistic regression models adjusting for relevant covariates examined the independent association between travel distance and patient outcomes.

Results

Our study included 2,136 patients with IBD (1,197 CD, 939 UC) among just over half were women (52%) and the mean age was 41 years. The mean distance from our hospital was 2.5 miles, 8.8 miles, 22.0 miles, and 50.8 miles for the first (most proximal) through fourth (most distant) respectively. We observed a statistically significant and meaningful higher risk among patients in the most distant quartile in the need for immunomodulator use (OR 1.69, 95% CI 1.29–2.22), biological therapy (OR 2.19, 95% CI 1.69–2.85) and surgery (OR 2.44, 95% CI 1.80 – 3.32). Differences remained significant on multivariable analysis and by type of IBD.

Conclusion

Greater distance to referral healthcare center was associated with increased risk for needing IBD-related surgery in patients with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis.

Keywords: travel distance, inflammatory bowel disease, surgery, biologics, immunomodulators

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) comprising Crohn’s disease (CD) and Ulcerative Colitis (UC) affect an estimated 1.6 million individuals in the United States with as many as 70,000 new patients diagnosed each year.1 They are complex, relapsing-remitting diseases frequently leading to hospitalizations, surgery, and permanent bowel damage. Advances in therapeutics have increased the number of treatment options, expanding the armamentarium from broad conventional immunomodulator therapy to targeted biologics and small molecules including monoclonal antibodies to tumor necrosis factor α (anti-TNF) and gut-specific mucosal integrins.2, 3 However, this has also resulted in care for IBD becoming increasingly complex and specialized with evolution towards therapeutic paradigms that suggest better outcomes with adoption of upfront biologic therapy early on in disease course and in combination with a conventional immunomodulators.4, 5

Several studies have examined the impact of specialist care on outcomes of patients with IBD.6, 7 Care at a high IBD volume hospital is associated with lower post-operative mortality among patients undergoing surgery.8, 9 Among hospitalized patients with UC, gastroenterologist care was associated with lower mortality for up to 1 year after the initial hospitalization compared to admissions under internists and general practitioners.6 Even in a tertiary referral center, care by gastroenterologists specializing in IBD resulted in superior post-hospitalization outcomes and earlier access to IBD-related surgical interventions.7 The impact of barrier to effective care may extend even prior to the diagnosis of IBD where a delay may reduce response to medical therapy, increase risk of fibrostenosis and need for surgery.10, 11

A delay in receiving effective therapy may not be solely due to patient behavior or physician expertise, but could also be determined by barriers to access quality IBD care. One such factor that may hinder access to specialist IBD care may be the physical distance from such facilities. Prior studies examining the impact of distance from a hospital have focused on medical or surgical emergencies, demonstrating that in three-quarters of such studies, there existed a “distance decay” relationship with worse outcomes in patients living further away from the site of care.12 One can envision that distance from care may also be relevant in diseases like IBD that are beset by unpredictable flares, requires periodic clinical and endoscopic evaluation to ensure remission, and rely on long-term adherence to therapy that requires a regular patient-provider relationship. Consequently, we performed this study with aim of examining the impact of distance from area of residence to a referral IBD center on the need for surgery and biologic therapy in patients with CD and UC.

METHODS

Study population

The study cohort consisted of patients recruited for the Prospective Registry in IBD Study at Massachusetts General Hospital (PRISM). This prospective cohort is an ongoing registry of patients that is open to all adult patients with an established diagnosis of IBD who received longitudinal care at the Massachusetts General Hospital. Upon provision of informed consent, all patients completed an enrollment interview with a study research coordinator where demographics, disease characteristics, and history of medical and surgical treatments were obtained. All information was confirmed by medical record review.

Covariates and Outcomes

Our main exposure of interest was distance from zip code of residence to our hospital (MGH). The zip code was obtained from the residential address field of the electronic medical record and distance calculated using a distance calculator (https://www.zip-codes.com/distance_calculator.asp). This distance was modeled in quartiles with the higher quartiles increasingly further away from the hospital. Other covariates obtained include gender, age at enrollment and at diagnosis, disease duration, and smoking status. Disease location and behavior in CD and extent in UC were classified according to the Montreal classification.13 We also obtained information on education and employment status. Patients reporting a Bachelor’s degree or higher were considered “highly educated”. Engagement in employment was defined as performing paid work or being a student.

Our primary outcome was need for IBD-related surgery. Our secondary outcomes were need for biologic (infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, golimumab, natalizumab, or vedolizumab) therapy or immunomodulators (azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, methotrexate).

Statistical analysis

All analysis was performed using Stata 13.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Continuous variables were summarized using means and standard deviations while categorical variables were expressed as proportions and compared using the chi-square test. We first performed univariate analysis examining the association between distance quartiles and each of our study outcomes. Subsequently, multivariable models were constructed adjusting for disease-specific covariates including duration of disease, behavior and extent of involvement, education, and employment status. A p-value <0.05 in this analysis was considered to indicate independent statistical significance. Various sensitivity analyses were performed, excluding patients residing more than 25 miles and 50 miles away to minimize the potential for bias introduced by a referral population. Approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Massachusetts General Hospital.

RESULTS

Study cohort

Our cohort included 2,136 patients with IBD (1,197 CD, 939 UC) with a mean age of 41 years. Just over half (52%) were women. After excluding patients who lived more than 100 miles away from our hospital (likely representing a referral population) (n=112), we included 2,024 patients in our final analysis. The patients excluded from the study were similar to the final cohort in age and sex, type of IBD and paid work, but were more likely to have CD and be highly educated compared to included patients. Dividing the cohort into quartiles based on proximity, the mean distance from zip code of residence to our hospital was 2.5 miles (±1.4), 8.8 miles (±2.6), 22.0 miles (±5.0), and 50.8 miles (±16.5) for the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th quartiles respectively. There were no differences in sex, type of IBD, location or behavior of CD, perianal involvement, and extent of UC between patients living near or far from our hospital (Table 1). Patients with a greater distance to the hospital were slightly older, were diagnosed with IBD at an older age, had a longer duration of disease, and were more likely to have a history of smoking. They were also less likely to be doing paid work or have a Bachelor’s degree or higher.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics

| Quartile 1 (n=469) |

Quartile 2 (n=526) |

Quartile 3 (n=563) |

Quartile 4 (n=466) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female, n(%) | 248 (52.9) | 278 (52.9) | 287 (51.0) | 241 (51.7) | 0.909 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 35.1 (±12.8) | 42.3 (±16.1) | 43.0 (±14.9) | 42.2 (±15.0) | 0.044 |

| Age at diagnosis, mean (SD) | 25.4 (±12.1) | 30.8 (±14.6) | 30.3 (+14.3) | 30.0 (±14.3) | 0.023 |

| Duration disease, mean (SD) | 9.6 (±9.0) | 11.3 (±12.1) | 12.6 (±11.9) | 11.9 (±11.2) | <0.001 |

| Smoking, n(%) | 0.001 | ||||

| Never | 341 (74.5) | 326 (63.8) | 353 (63.7) | 278 (61.1) | |

| Former | 96 (20.96) | 142 (27.8) | 164 (29.6) | 143 (31.4) | |

| Current | 21 (4.6) | 43 (8.4) | 37 (6.7) | 34 (7.5) | |

| High level education, n(%) | 394 (87.56) | 354 (69.01) | 345 (63.7) | 260 (58.2) | <0.001 |

| Working, n(%) | 409 (88.9) | 403 (77.7) | 418 (75.3) | 352 (77.9) | <0.001 |

| IBD type, n(%) | 0.157 | ||||

| CD | 243 (51.8) | 285 (54.2) | 326 (57.9) | 269 (57.7) | |

| UC | 226 (48.2) | 241 (45.8) | 237 (42.1) | 197 (42.3) | |

| CD location, n(%) | 0.801 | ||||

| TI (L1) | 57 (25.8) | 61 (24.0) | 75 (25.7) | 61 (26.0) | |

| Colon (L2) | 53 (24.0) | 70 (27.6) | 73 (25.0) | 55 (23.4) | |

| Ileocolon (L3) | 111 (50.23) | 122 (48.0) | 144 (49.3) | 117 (49.8) | |

| Upper GI (L4) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.9) | |

| CD behavior, n(%) | 0.060 | ||||

| Inflammatory (B1) | 129 (57.6) | 135 (50.9) | 136 (45.6) | 108 (44.4) | |

| Stricturing (B2) | 39 (17.4) | 58 (21.9) | 62 (20.8) | 60 (24.7) | |

| Penetrating (B3) | 56 (25.0) | 72 (27.2) | 100 (33.6) | 75 (30.9) | |

| CD perianal disease, n(%) | 55 (24.6) | 70 (26.4) | 79 (26.5) | 65 (26.8) | 0.946 |

| UC extent, n(%) | 0.425 | ||||

| Limited colitis | 88 (44.4) | 103 (47.9) | 104 (49.5) | 67 (41.6) | |

| Pancolitis | 110 (55.6) | 112 (52.1) | 106 (50.5) | 94 (58.4) |

The mean distance from our hospital was 2.5 miles, 8.8 miles, 22.0 miles, and 50.8 miles for the first (most proximal) through fourth (most distant) respectively.

Distance from hospital and disease outcomes

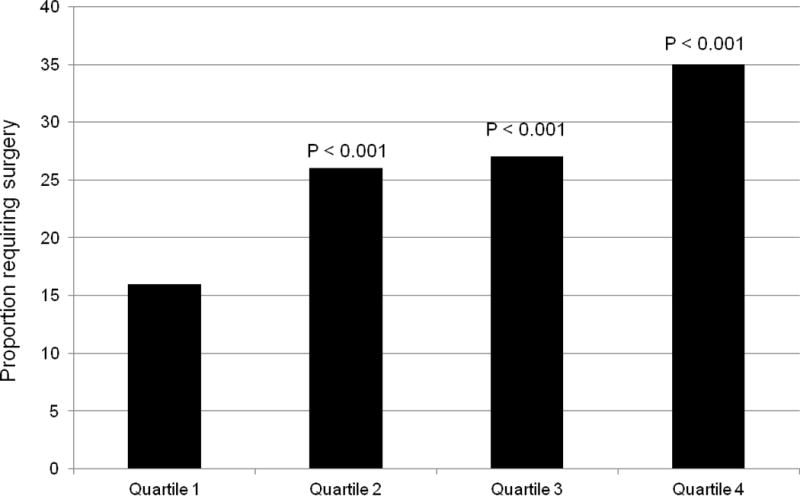

Patients living in the most distant quartile were significantly more likely to need IBD-related surgery than those living closer to the hospital (OR 2.44, 95% CI 1.80 – 3.32) (Table 2) (Figure 1). A dose-response relationship was seen with progressively greater likelihood for surgery in quartile 2 (OR 1.68, 95% CI 1.23 – 2.28) and 3 (OR 1.94, 95% CI 1.44 – 2.62). A similar relationship was also noted in biologic therapy where patients in the most distant quartile had a two-fold increase in need in comparison with patients living near the hospital (OR 2.19, 95% CI 1.69–2.85). For immunomodulator use, a significantly elevated odds ratio was noted only among patients in the most distant quartile compared to those living the closest (OR 1.69, 95% CI 1.29–2.22); no effect was noted in the 2nd and 3rd quartiles.

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of impact of travel distance on need for IBD-related surgery, biologic, and immunomodulator use

| Outcome | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Need for surgery (q1=reference) | |||

| Quartile 1 | 1.00 | Reference | |

| Quartile 2 | 1.68 | 1.23 – 2.28 | 0.001 |

| Quartile 3 | 1.94 | 1.44 – 2.62 | <0.001 |

| Quartile 4 | 2.44 | 1.80 – 3.32 | <0.001 |

| Need biologic therapy (q1=reference) | |||

| Quartile 1 | 1.00 | Reference | |

| Quartile 2 | 1.10 | 0.85 – 1.41 | 0.486 |

| Quartile 3 | 1.51 | 1.18 – 1.94 | 0.001 |

| Quartile 4 | 2.19 | 1.69 – 2.85 | <0.001 |

| Need immunomodulator therapy (q1=reference) | |||

| Quartile 1 | 1.00 | Reference | |

| Quartile 2 | 0.82 | 0.64 – 1.06 | 0.130 |

| Quartile 3 | 1.20 | 0.93 – 1.54 | 0.158 |

| Quartile 4 | 1.69 | 1.29 – 2.22 | <0.001 |

Figure 1. Relationship between distance from hospital and need for surgery in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases.

The mean distance from our hospital was 2.5 miles, 8.8 miles, 22.0 miles, and 50.8 miles for the first (most proximal) through fourth (most distant) respectively.

These findings remained significant on our multivariable analysis. Each progressively further quartile was associated with a greater need for surgery in all IBD patients adjusting for age, type of IBD, duration of disease and engagement in paid employment. Patients residing in the most distant quartile were two-times as likely to need surgery as those residing closest to the hospital (OR 1.98, 95% CI 1.36–2.89). This relationship also persisted in the need for biologic therapy (Q4 vs. Q1: OR 2.18, 95% CI 1.60–2.97), and for the most distant quartile – the need for immunomodulator therapy (Q4 vs. Q1; OR 1.61, 95% CI 1.19–2.21). Similar results were obtained when distance from the hospital was modeled as a continuous variable with each 10 mile increase in distance being associated with an increased risk for surgery (OR 1.09, 95% CI 1.03 – 1.16, p=0.004) and biologic therapy (OR 1.14, 95% CI 1.08 – 1.20, p<0.001).

Subgroup Analysis

We performed subgroup analysis by type of IBD. In CD, additionally adjusting for the perianal involvement, disease location and behavior, higher quartiles of distance was associated with an increasing likelihood of surgery and biologic therapy (Table 3). For example, patients living in the most distant quartile had a two-fold increase in need for surgery (OR 1.75, 95% CI 1.04 – 2.97) and biologic therapy (OR 2.40, 95% CI 1.54 – 3.75). A similar effect was also noted in UC, additionally adjusting for disease extent. There was a three-fold greater need for surgery (OR 3.31, 95% CI 1.34 – 8.88) and two-fold increase in biologic therapy (OR 2.02, 95% CI 1.22 – 3.33) between the most distant and closest quartiles.

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis of impact of travel distance on need for IBD-related surgery, biologic, and immunomodulator use

| Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Crohn’s disease* | OR (95%CI) | p-value | OR (95%CI) | p-value | OR (95%CI) | p-value |

| Need surgery | 1.47 (0.88–2.48) | 0.143 | 1.31 (0.79–2.17) | 0.304 | 1.75 (1.04–2.97) | 0.036 |

| Need biologics | 1.29 (0.84–1.97) | 0.240 | 1.61 (1.05–2.46) | 0.029 | 2.40 (1.54–3.75) | <0.001 |

| Need immunomodulator | 0.72 (0.47–1.12) | 0.144 | 0.84 (0.54–1.30) | 0.431 | 1.24 (0.78–1.97) | 0.367 |

|

| ||||||

| Ulcerative colitis** | OR (95%CI) | p-value | OR (95%CI) | p-value | OR (95%CI) | p-value |

|

| ||||||

| Need surgery | 2.75 (1.12–6.77) | 0.028 | 2.07 (0.82–5.26) | 0.122 | 3.31 (1.34–8.22) | 0.010 |

| Need biologics | 1.24 (0.76–2.03) | 0.380 | 2.02 (1.23–3.31) | 0.005 | 2.02 (1.22–3.33) | 0.006 |

| Need immunomodulator | 0.89 (0.57–1.38) | 0.596 | 1.54 (0.98–2.43) | 0.061 | 1.96 (1.22–3.16) | 0.005 |

Quartile 1 is the reference quartile.

Adjusted for perianal disease, CD location and behavior

Adjusted for UC extent

Sensitivity Analysis

To further minimize referral bias where patients with more aggressive disease are referred to us for specialized care, we performed sensitivity analysis excluding patients who lived 50 miles or more from our hospital. This showed a similar effect on multivariable analysis as with our primary analysis. All three outcomes remained statistically significant with an increasing likelihood of surgery (OR 1.82, 95% 1.20 – 2.79), biologic therapy (OR 2.55, 95% CI 1.78 – 3.65) and immunomodulator therapy (OR 1.76, 95% CI 1.22 – 2.54) between the most distant and closest quartiles.

DISCUSSION

Treatment of IBD is complex and increasingly specialized. With expansion of the number of treatment options, therapeutic drug monitoring, and recognition of more robust treatment goals such as early attainment of mucosal healing, management of IBD increasingly requires close and frequent contact between the patient and the treatment team, with dynamic alterations of therapeutic strategies. However, physical access to specialized healthcare is not always easy and patients frequently have to travel long distances to receive such care, which in turn, may impact initiation and optimization of medical therapy. The impact of travel distance from a referral IBD hospital on patients’ outcomes has not been examined previously. In a study from a single referral center, we demonstrated that greater distance from specialized care was associated with a higher risk for IBD-related surgery, and need for biologic or immunomodulator therapy. Our findings were robust to a range of assumptions of distances travelled excluding referral patients, and on adjustment for various disease related characteristics.

A few prior studies have examined the impact of specialized care on patients with IBD.6, 8, 9, 14 Murthy et al. assessed the impact of gastroenterologist care and observed a three to four-fold lower mortality among hospitalized UC patients when under the care of a gastroenterologist.6 A similar result was seen in studies assessing the impact of hospital volume on outcomes of IBD-related hospitalizations. IBD patients undergoing surgery at high IBD volume admission centers had lower in-hospital and postoperative mortality.8, 9, 15 Even within a single referral hospital, implementation of specialized IBD care pathway and dedicated care by a gastroenterologist specializing in IBD was associated with higher rates of remission at 3 months and facilitated early surgical intervention.7 Equivalent results were observed in studies assessing the influence of specialized care in other diseases.16–20 Thus overall, evidence suggests that the best outcomes in IBD may be obtained in specialized setting, particularly for patients at risk for more severe disease or requiring complex, multidisciplinary care.

The impact of travel distance on patient outcomes has been examined before for other indications and elegantly summarized in a systematic review by Kelly et al.12 Over three-quarters of the examined studies demonstrated a distance-decay association with worse outcomes in individuals living further away from healthcare facilities. In our study, distance from the referral hospital was associated with greater need for surgery, immunomodulator, and biologic therapy. Greater travel distance may impact need for surgery in patients with IBD by impeding early initiation of effective treatment. Though in our study, the findings for biologic or immunomodulator therapy may be inverse to what one may expect, with patients residing close to the hospital more likely to be initiated on biologic therapy, this may not capture the effect of timing of initiating of such therapy. While there is robust data supporting the efficacy of biologic therapy in reducing surgery and hospitalizations in IBD, the timing of initiation of such therapy appears to be key. Prior studies have demonstrated that delayed initiation of biologic or immunomodulator therapy, particularly after chronic bowel damage and fibrostenosing complications has set in may not result in an optimal benefit.21–25 Longer distance from the hospital may also affect patient adherence to treatment by impeding a robust patient-provider relationship which exerts an strong influence on adherence to recommendations.26–28 Non-adherence in turn, has been associated with worse outcomes in IBD.29 Longer distance may also interfere with ongoing monitoring using serologic markers, endoscopies and drug levels, thereby not allowing optimization of therapy.

We readily acknowledge a few sources of bias that may influence interpretation of our study results. First, it is possible that patients residing furthest away from hospital are referred to us for more severe disease. This is unlikely to be the sole explanation for our findings for a few reasons. First, our findings remained significant on restricting travel distances to within 25 or 50 miles, and it is unlikely that patients within this proximal vicinity are referral cases alone. Second, at our center, patients are recruited into our patient registry after the third visit (often later) to our offices, and are not one-time consultation referrals. A third limitation is that we did not have information on the duration of disease at immunomodulator or biologic initiation. It is important for future studies to be able to address for this and account for delay in initiation of effective treatment. We also acknowledge some limitations in our study. While we focused on a hard-endpoint of surgery that contributes significant weight to disease damage indices like the Lemann index, it is important to also examine additional endpoints such as early attainment of mucosal healing using ‘treat-to-target’ strategies.

There are a few implications to our findings. Several studies have proposed centralization of health care services to improve outcomes, minimize regional differences in the quality of care, and reduce costs.30, 31 However, often centralized high volume centers offering specialized care are necessarily located in large metropolitan centers, leading to increased travel distance (and consequently, reduced access) for patients residing in less populated areas further away.32 As demonstrated in our study, this increased travel distance may result in worse patient outcomes or reduce the benefit of getting specialized care. While it may be logistically difficult for most of complex IBD care to be restricted to a few specialized centers, it is of greater importance to define what components of specialized IBD care are associated with improved patient outcomes and to replicate such care in the community. The development of quality metrics by professional societies and organizations33–35 is an important step in that regard. Education of care-providers at all levels, from gastroenterologists to primary care physicians, mid-level providers, and nurses including those specializing in IBD would also help provide optimal high-quality IBD-care to all patients. Another solution to overcome the challenge of physical distance may be wider use of technology to deliver specialized care through telemedicine. Several models exist demonstrating the feasibility and value of such care for providing both patient care and provider education. Efficient delivery of high-quality specialized IBD care attains particular importance with rising IBD-related healthcare costs. Early, effective therapy that decreases likelihood of disease damage is important in reducing IBD-related costs over the lifetime of a patient.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that greater distance from a referral IBD hospital was associated with greater need for IBD-related surgery, immunomodulator, and biologic therapy. There is need for further studies to determine how specialized IBD care may be provided in a de-centralized way to optimize patient outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Source of funding: This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (P30 DK043351) to the Center for Study of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Ananthakrishnan is supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (K23 DK097142).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Ananthakrishnan has served on scientific advisory boards for Abbvie, Takeda, and Merck.

References

- 1.Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America. The facts about Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Accessed: November 2016 http://www.ccfa.org/assets/pdfs/updatedibdfactbook.pdf.

- 2.Bernstein CN. Treatment of IBD: where we are and where we are going. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:114–26. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grevenitis P, Thomas A, Lodhia N. Medical Therapy for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Surg Clin North Am. 2015;95:1159–82. vi. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moss AC, Kim KJ, Fernandez-Becker N, et al. Impact of concomitant immunomodulator use on long-term outcomes in patients receiving scheduled maintenance infliximab. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1413–20. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0856-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ward MG, Irving PM, Sparrow MP. How should immunomodulators be optimized when used as combination therapy with anti-tumor necrosis factor agents in the management of inflammatory bowel disease? World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:11331–42. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i40.11331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murthy SK, Steinhart AH, Tinmouth J, et al. Impact of gastroenterologist care on health outcomes of hospitalised ulcerative colitis patients. Gut. 2012;61:1410–6. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Law CC, Sasidharan S, Rodrigues R, et al. Impact of Specialized Inpatient IBD Care on Outcomes of IBD Hospitalizations: A Cohort Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:2149–57. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ananthakrishnan AN, McGinley EL, Binion DG. Does it matter where you are hospitalized for inflammatory bowel disease? A nationwide analysis of hospital volume. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2789–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaplan GG, McCarthy EP, Ayanian JZ, et al. Impact of hospital volume on postoperative morbidity and mortality following a colectomy for ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:680–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moon CM, Jung SA, Kim SE, et al. Clinical Factors and Disease Course Related to Diagnostic Delay in Korean Crohn’s Disease Patients: Results from the CONNECT Study. PLoS One. 2015;2010:e0144390. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schoepfer AM, Dehlavi MA, Fournier N, et al. Diagnostic delay in Crohn’s disease is associated with a complicated disease course and increased operation rate. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1744–53. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.248. quiz 1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelly C, Hulme C, Farragher T, et al. Are differences in travel time or distance to healthcare for adults in global north countries associated with an impact on health outcomes? A systematic review. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e013059. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, et al. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19(Suppl A):5A–36A. doi: 10.1155/2005/269076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen GC, Nugent Z, Shaw S, et al. Outcomes of patients with Crohn’s disease improved from 1988 to 2008 and were associated with increased specialist care. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:90–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen GC, Steinhart AH. Nationwide patterns of hospitalizations to centers with high volume of admissions for inflammatory bowel disease and their impact on mortality. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1688–94. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richardson AJ, Pang TC, Johnston E, et al. The volume effect in liver surgery–a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:1984–96. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2314-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buettner S, Gani F, Amini N, et al. The relative effect of hospital and surgeon volume on failure to rescue among patients undergoing liver resection for cancer. Surgery. 2016;159:1004–12. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salz T, Sandler RS. The effect of hospital and surgeon volume on outcomes for rectal cancer surgery. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1185–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vernooij F, Heintz P, Witteveen E, et al. The outcomes of ovarian cancer treatment are better when provided by gynecologic oncologists and in specialized hospitals: a systematic review. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105:801–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giede KC, Kieser K, Dodge J, et al. Who should operate on patients with ovarian cancer? An evidence-based review. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;99:447–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma C, Beilman CL, Huang VW, et al. Anti-TNF Therapy Within 2 Years of Crohn’s Disease Diagnosis Improves Patient Outcomes: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:870–9. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walters TD, Kim MO, Denson LA, et al. Increased effectiveness of early therapy with anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha vs an immunomodulator in children with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:383–91. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gonzalez-Lama Y, Suarez C, Gonzalez-Partida I, et al. Timing of Thiopurine or Anti-TNF Initiation Is Associated with the Risk of Major Abdominal Surgery in Crohn’s Disease: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:55–60. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kariyawasam VC, Selinger CP, Katelaris PH, et al. Early use of thiopurines or methotrexate reduces major abdominal and perianal surgery in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1382–90. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schreiber S, Colombel JF, Bloomfield R, et al. Increased response and remission rates in short-duration Crohn’s disease with subcutaneous certolizumab pegol: an analysis of PRECiSE 2 randomized maintenance trial data. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1574–82. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bristow RE, Chang J, Ziogas A, et al. Spatial analysis of adherence to treatment guidelines for advanced-stage ovarian cancer and the impact of race and socioeconomic status. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;134:60–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.03.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plevinsky JM, Greenley RN, Fishman LN. Self-management in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: strategies, outcomes, and integration into clinical care. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2016;9:259–67. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S106302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sewitch MJ, Abrahamowicz M, Barkun A, et al. Patient nonadherence to medication in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1535–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herman ML, Kane SV. Treatment Nonadherence in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Identification, Scope, and Management Strategies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:2979–84. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhattarai N, McMeekin P, Price C, et al. Economic evaluations on centralisation of specialised healthcare services: a systematic review of methods. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011214. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kobayashi D, Otsubo T, Imanaka Y. The effect of centralization of health care services on travel time and its equality. Health Policy. 2015;119:298–306. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Halm EA, Lee C, Chassin MR. Is volume related to outcome in health care? A systematic review and methodologic critique of the literature. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:511–20. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-6-200209170-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siegel CA, Allen JI, Melmed GY. Translating improved quality of care into an improved quality of life for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:908–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shah R, Hou JK. Approaches to improve quality of care in inflammatory bowel diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:9281–5. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i28.9281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.American Gastroenterology Association. Accessed: Novemebr 2016 Available form: URL: http://www.gastro.org/practice-management/measures/2016_AGA_Measures_-_IBD.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.