Introduction

Primary cerebral hemiatrophy refers to a condition in which there is atrophy or hypoplasia of one cerebral hemisphere due to a prenatal and ongoing cause [1]. These patients present with seizure disorder, mental retardation and hemiparesis [2, 3]. The pathological process shows a generalized shrinkage of the affected cerebral hemisphere with all lobes involved. The affected hemisphere has the same convolutional pattern as on the normal side but the gyri are smaller and sulci wider on the affected side [3]. The cortical mantle may be half the thickness, the ipsilateral pyramidal tract is small and the cerebral vessels are unusually small [2, 4]. The midline and the falx attachment are shifted to the same side. The calvaria shows compensatory hypertrophy [1, 3]. In short, it is a hemisphere in miniature. We report the CT findings in two unusual cases of cerebral hemiatrophy that have reported in service hospitals in last 5 years.

Case no 1

A 5-year-old male boy reported with an attack of generalized seizure. There was no history suggestive of any head injury. There was no history of birth asphyxia. Clinical examination revealed evidence of mental retardation. Hemiparesis of right side was evident. No cutaneous manifestation like nevus was present. CT scan of head (Figs 1 a & b) revealed reduced size of gyri with widened sulci on the left cerebral hemisphere. Ipsilateral displacement of the midline structures like falx and third ventricle was seen. The left lateral ventricle was minimally widened than the right side. Left sided bony calvarium and mastoid air cells showed mild enlargement in size. The posterior fossa structures were normal. There was no evidence of any focal lesion or scarring suggesting old injury or infarction.

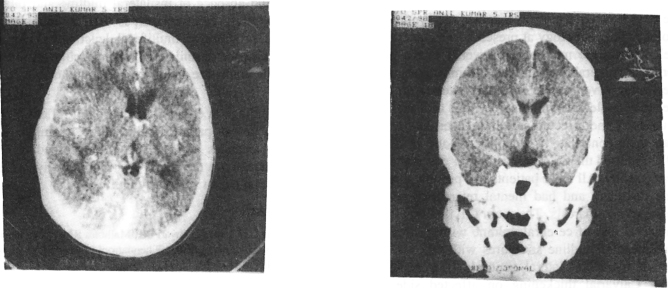

Fig. 1a & b.

The axial 1 (a) and coronal 1 (b) images showing cerebral hemiatrophy involving the left cerebral hemisphere with compensatory calvarial changes. Note the displacement of the falx attachment

Case no 2

A 19-year-old male reported with history of recurrent attacks of generalised clonic tonic seizures from first year of life for which he was on treatment. There was no history of head injury in infancy and no history of birth trauma or birth asphyxia. Clinical examination revealed hemiparesis involving the right side. No nevus like cutaneous manifestation was seen. The patient had mild mental retardation. EEG showed epileptic activity from a left-sided focus with secondary generalization. CT scan of head (Fig 2 a & b) revealed reduced size of the gyri with widened sulci on the left cerebral hemisphere with ipsilateral displacement of the midline structures. The falx attachment was also displaced to the left. The left lateral ventricle was minimally dilated. The calvarium, base of skull and mastoid air cells showed compensatory enlargement in size. The posterior fossa structures were normal. There was no focal lesion in either hemisphere. There was no ulegyria (scarring) or agyria in either hemisphere.

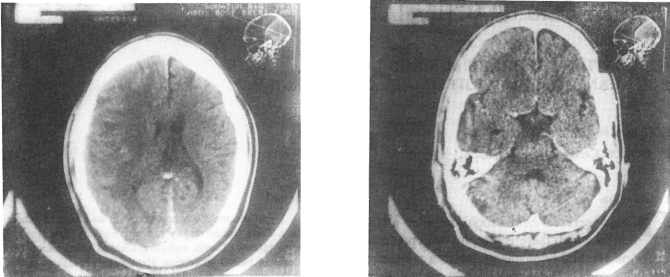

Fig. 2a & b.

The axial 2 (a) and coronal 2 (b) images showing cerebral hemiatrophy involving the left cerebral hemisphere. Note the displacement of the falx attachment with normal posterior fossa.

Discussion

So far just over a dozen cases of primary cerebral hemiatrophy have been described [1]. The early accounts of this condition are unsatisfactory. For the most part the condition was accepted as being due to birth trauma and hypoxia. Josephy in 1945 [1, 4] was the first to adequately put together the syndrome pathology. The pathology at present is speculative. As is well known, the microscopic layer 3 of the cerebral cortex is vulnerable to anoxia. But in primary atrophy the lesion is very extensive and extends far beyond the area of selective vulnerability. It is as if the cortical neurons of the affected side have been less endowed than their contralateral side [2]. Jacoby et al [3] in 1977 reported the CT findings in four cases of cerebral hemiatrophy. All these patients had presented with seizure disorders and had mental retardation with evidence of hemiparesis. The main CT findings included unilateral loss of cerebral volume with ipsilateral displacement of midline structures with falx and dilatation of ipsilateral lateral ventricle (features of atrophy). Calvarial thickening on affected side (likely compensatory) was seen. All these features are seen in both our cases. He emphasized that the coexistent calvarial thickening and the displacement of the falx attachment indicate that the process began before or during the greatest growth of the calvarium. Most of these cases live into the adult life, the oldest reported being 69 years [1, 2, 4]. In few cases the hemiparesis was of infantile type, in some others the hemiparesis was noticed after some childhood illness.

The differential diagnoses primarily include hemiatrophy due to trauma in infancy, Sturge-Weber syndrome and progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy. Sturge-Weber Syndrome (encephaltrigeminal angiomatosis) represents cerebral atrophy associated with leptomeningeal angioma [3]. The patients have seizure disorders, mental retardation and hemiparesis. The distinguishing features are presence of port-wine facial nevus and intracranial calcification and absence of ipsilateral midline and falx attachment shift. Midline shift is seen in late atrophic stage of progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy but the absence of unilateral calvarial changes and decrease in brain size helps to differentiate this condition.

CT findings in cerebral hemiatrophy reflect the underlying gross pathological changes. Compensatory calvarial changes indicate that the observed cerebral abnormalities are the result of atrophic or hypoplastic process that began very early in life.

REFERENCES

- 1.Satija L, Kumar A, Tiwari PK, Malhotra RM. Imaging diagnosis of primary cerebral hemiatrophy. Journal of Applied Medicine. 1994;7(7):541. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson RG. Agenesis anomalies of other brain structures. In: Vinken JP, Bruyen GW, Klawans HL, eds. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, Amsterdam Elsevier Science Publishers. 1987;50:204–206. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacoby CG, Go RT, Hahn FJ. Computed tomography in cerebral hemiatrophy. AJR. 1977;129:5–7. doi: 10.2214/ajr.129.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Josephy J. Cerebral Hemiatrophy (Diffuse sclerotic type of Schob) J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1945;4:250–261. [Google Scholar]