Abstract

Hypothesis

Proinflammatory cytokine Interleukin (IL)-17A (IL-17A) is overexpressed in a subset of patients with lung cancer. We hypothesized that IL-17A promotes a pro-tumorigenic inflammatory phenotype, and inhibits anti-tumor immune responses.

Experimental Design

We generated bi-transgenic mice expressing a conditional IL-17A allele along with conditional KrasG12D and performed immune phenotyping of mouse lungs, survival analysis, and treatment studies with antibodies either blocking PD-1 or IL6, or depleting neutrophils. To support preclinical findings, we analyzed human gene expression datasets and immune profiled patient lung tumors.

Results

Tumors in IL-17:KrasG12D mice grew more rapidly, resulting in a significantly shorter survival as compared to KrasG12D. IL-6, G-CSF, MFG-E8, and CXCL1 were increased in the lungs of IL17:Kras mice. Time course analysis revealed that tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) were significantly elevated, and lymphocyte recruitment was significantly reduced in IL17:KrasG12D mice as compared to KrasG12D. In therapeutic studies PD-1 blockade was not effective in treating IL-17:KrasG12D tumors. In contrast, blocking IL-6 or depleting neutrophils with an anti-Ly-6G antibody in the IL17:KrasG12D tumors resulted in a clinical response associated with T cell activation. In tumors from lung cancer patients with KRAS mutation we found a correlation among higher levels of IL-17A and the colony stimulating factor (CSF3), and a significant correlation among high neutrophil and lower T cell numbers.

Conclusions

Here we show that an increase in a single cytokine, IL-17A, without additional mutations, can promote lung cancer growth by promoting inflammation, which contributes to resistance to PD-1 blockade and sensitizes tumors to cytokine/neutrophil depletion.

Keywords: cytokines, IL-17, neutrophils, MDSC, PD-1, checkpoint blockade, resistance

Introduction

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths world-wide. Targeted therapies are effective in a subset of lung cancers carrying specific mutations in genes such as EGFR or genetic fusions such as EML4-ALK, but there remains a need for therapies specific for KRAS mutant tumors, which constitute about 30% of all adenocarcinomas and are currently refractory to targeted therapies 1, 2. Activating mutations in KRAS are associated with smoking and resistance to EGFR inhibitors3–5. Smoking has been associated with not only initiation of lung cancer by the carcinogens it carries, but also the promotion of tumor development through inducing inflammation by activation of the NFκB pathway 6, 7. In preclinical models NFκB was shown to be required for Kras induced lung tumorigenesis 8.

The presence of cytokines and inflammatory cells in the lung microenvironment plays a crucial role in determining the outcome of the host anti-tumor response. Cytokines are released in response to cellular stress, injury, or infection, and stimulate the restoration of tissue homeostasis to restrict tumor development and progression. However, persistent cytokine secretion in the setting of unresolved inflammation can promote tumor cell growth, inhibit apoptosis, and drive tumor cell invasion and metastasis 9. Though the exact mechanisms by which inflammation or inflammatory cells regulate lung cancer growth is not clear, increases in certain components such as circulating IL-6 10 or a higher neutrophil to T cell ratio in lung tumors are associated with a poor prognosis in lung cancer 11, 12.

IL-17A is the prototypical member of the IL-17 family of pro-inflammatory cytokines. It is produced by Th17 cells, CD8 T cells, γδT cells, and Natural Killer (NK) cells in the tumor microenvironment 13. Interaction of IL-17 with its receptor, which is expressed on a variety of cell types including fibroblasts and tumor cells, causes secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, various chemokines, and metalloproteases 14–18. The inflammatory milieu can contribute to lung cancer growth by further production of tumor promoting cytokines, reduction in cytotoxic T cells, and development of myeloid derived suppressor cells 19. IL-17A and its receptors are expressed across different tumor types; however, their exact role in tumor development, progression, and response to therapeutic regimens is unclear. In melanoma, IL-17A serves as a tumor suppressor; IL-17A knockout mice are more susceptible to spontaneous melanoma development 20. In contrast, IL-17A knockout mice are protected from intestinal tumorigenesis in an Adeno Apcflox/+ model 16. Increased presence of IL-17A positive cells is associated with poor survival in NSCLC 21, 22. IL-17A was shown to be critical in Kras induced lung tumorigenesis in a mouse model lacking IL-17A that expressed Kras from the clara cell (CC10) promoter, though this mouse model develops tumors very rapidly 23.

While targeted therapies developed against mutant EGFR or EML4-ALK proteins are only effective in specific subsets of NSCLC patients 24, 25, immune checkpoint blockade treatments that activate host anti-tumor immunity are effective in about 20% of NSCLC patients across a variety of genotypes 26. Though tumor or myeloid cell PD-L1 expression or increased tumor mutational burden, which can potentially be detected by the immune cells as neo-antigens, are associated with a better response to PD-1 blockade treatment 27–29, other predictive biomarkers for response and resistance remain to be discovered. It also remains unclear whether cytokines or the immune cell context of tumors determines the efficacy of checkpoint blockade.

IL-17A is expressed at high levels in a subset of lung cancers 21. Interestingly, we observed that IL-17A could not be detected in Bronchoalveolar lavage fluids (BALFs) from immunocompetent mouse lung cancer models from previously described EGFRT790M L858R, EGFRDel19, KrasG12D, KrasG12D:Tp53 30–32. Of note, Kras mutant tumors in this study were induced after adenovirus administration, which results in fewer lung lesions compared to CC10-Cre induced mice 33, 34. To characterize the role of IL-17A in Kras mutant lung tumors, we developed a mouse model of chronic inflammation that more closely resembles human KRAS mutant lung cancer through expressing IL-17A constitutively in the lung epithelium and then introducing this allele into lox-stop-lox KrasG12D mutant mice. We found that the production of this single cytokine dramatically changed immune cell dynamics in the tumor microenvironment and promoted resistance to PD-1 blockade.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of the IL17 transgenic mice

The targeting vector has been modified from the original pCAGGS FLPe vector described 6. Tet inducible promoter used in the original manuscript has been replaced with CAG promoter and lox-stop-lox cassette, which allows the temporal/spatial control of gene expression. Human IL-17A cDNA plasmid (pCR2-IL17) was purchased from Open Biosystems. IL-17 cDNA has been cloned into the cloning site after the stop cassette. Until the stop cassette is removed by Cre recombinase, transgene is not expressed.35 After cloning targeting vector and Flippase expressing plasmid were co-electroporated into the v6.5 C57BL/6(F) x 129/sv(M) ES cells (Open Biosystems, Waltham, MA #MES 1402) with plasmid expressing FLP recombinase 36. These ES are engineered to allow single copy transgene insertion at the ColA1 locus. ES clones that carry the transgene are selected, expanded, and used to inject into C57BL/6 blastocysts, which gave rise to the chimeras. Chimeras were bred with wild type mice from BALB/cAnNCrl (Charles River) background to test germline transmission of the transgene. Transgene positive mice were bred with Kras mice (B6.129S4-Krastm4Tyj/J) obtained from Jackson laboratories) and expanded for experiments. Mice were maintained in mixed background strain (C57BL/6, BALB/cAnNCrl, and 129/sv) and were given Adenovirus carrying Cre recombinase at 5×10^6 titer (University of Iowa) at 6 weeks of age to induce tumors. All mouse experiments were performed with the animal protocol approved by Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Mouse treatment studies

Mice were treated with IL-6 antibody (Clone: MP5-20F3, BioXcell cat # BE0046), Ly-6G antibody (Clone: 1A8, BioXcell cat # BE0075-1), and PD-1 antibody (clone 1A12-37, diluted in saline, 200 μg/dose three times a week by intraperitoneal injections. MRI imaging was performed using Bruker Biospec 7 Tesla MRI machine at Lurie Family Imaging Center at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

Cell line studies

Mouse cell lines were established from lung tumor nodules from Kras p53 mice. Tumor tissue was minced and trypsinized, and cells were grown in RPMI1640 containing 10% FBS 38. Cells were sorted for epithelial marker-Epcam to obtain pure tumor cell population as previously described 39. Human A549 and H1792 cell lines were purchased from ATCC. Recombinant human and mouse IL-17 and anti-mouse IL-17RA antibodies were purchased from PeproTech (200-17 and 210-17) and R&D systems (MAB4481) respectively, and used at the doses indicated in the figure based on manufacturers’ instruction.

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) Fluid collection and ELISA

BAL fluid was collected by intratracheal injection of 1 milliliter of saline into the mice after euthanasia and aspiration. Fluid was centrifuged, cells and debris pelleted, and the supernatant frozen for subsequent analysis. Cytokine and chemokines were measured with ELISA kits according to the manufacturer’s protocols IL-6, G-CSF (BD), and MFG-E8 and CXCL1 (R&D)

Immune analysis for mouse samples

Processing of lung tissue, staining, and flow cytometry analysis were performed as previously described 40. Mice were euthanatized according to IACUC approved animal protocol, and lungs were perfused with cold 5mM EDTA after collecting BAL fluid. Lung lobes were shredded and incubated in dissociation buffer (100 units/ml of collagenase type IV) (Invitrogen), 10 μg/ml of DNase I (Roche), and 10% FBS in RPMI1640 medium for 45 minutes. After dissociation, red blood cells (RBC) were lysed with RBC lysis buffer (Gibco-10492), and cell suspensions were passed through 70 micron cell strainer to isolate single cells. The cell pellet was dissolved in 2% FCS in HBSS, stained with Live/dead stain (Life Technologies, #L34959) per the manufacturer’s instructions. Staining antibodies were used at 1:50 dilution and used for flow cytometry analysis. For intracellular cytokine staining, cells from whole lungs were fractionated over Ficoll-Paque (GE Healthcare) per the manufacturer’s instructions. Isolated mononuclear cells were stimulated with 50 ng/ml PMA (Sigma) and 500 ng/ml Ionomycin (Sigma) for 4 hours in the presence of Golgi plug (BD Biosciences). Fixation/permeabilization buffers (eBioscience) or BD Cytofix/Cytoperm buffers (BD Biosciences) were used for intracellular staining. Flow data acquisition was performed on a BD Canto II flow cytometer.

Gene expression analysis from the TCGA dataset

21 EGFR and 74 KRAS mutant samples were used for analysis from the TCGA dataset1. Log2 of the FKPM for CSF-3 and IL-6, and Log2 of FKPM+1 for IL-17A from the RNA sequencing data were used for comparisons.

Immunohistochemistry staining and quantification

Tissues were fixed overnight in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin (FFPE). Ki67 IHC was performed using staining kits for Ki67 (Vector #VP-K451) following the manufacturer’s protocol. IL-17 IHC was performed using Santa Cruz antibody (SC7927) at 1:50 dilution. For Ki67 staining, Ki67 foci from the images taken at 20x magnification were quantified; three images per mouse were used.

Cytokine analysis of patient serum samples

Serum samples were obtained from the Harvard/MGH Lung Cancer Study (LCS). The HLCS is a hospital-based ongoing case-control study initiated in 1992. All cases were histological-confirmed lung cancer patients from the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Cancer Center 41. Controls were recruited from two sources, including: 1) case-related controls, who were friends and spouses of lung cancer cases with no specific matching characteristics – all blood-related friends/spouses were excluded; and 2) case-unrelated controls who were friends and spouses of other hospital patients – primarily from the oncology and thoracic surgery units – out of convenience, for cases who do not have available controls.

Immune cell analysis of freshly resected patient non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC)

De-identified patient tumors were obtained under IRB approved DFCI protocols 02-180 and 11-104 from subjects providing informed consent for tissue collection. Biopsies were obtained during routine clinical procedures. Human tissue processing and staining were performed following the same procedures as with mouse tissues. All antibodies were used as recommended by the manufacturer 42.

RESULTS

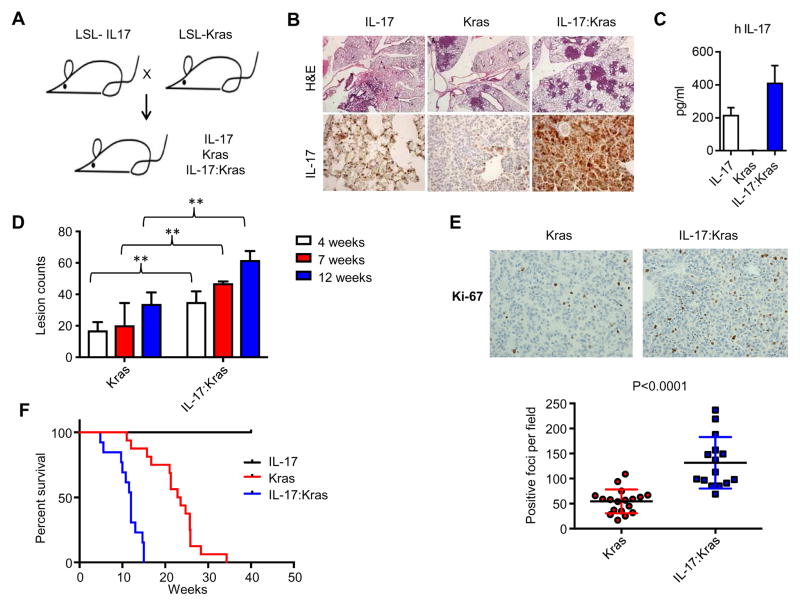

IL-17A promotes lung tumor growth through inducing production of IL-6

IL-17A is expressed in human lung tumors 21; however, IL-17A expression in diverse immunocompetent mouse models of lung cancer had not previously been assessed. We analyzed the IL-17A levels in the BALFs from a panel of lung GEMM models with comparable tumor burden. Interestingly, we did not detect IL-17A in the BALFs from adenovirally induced Kras driven (KrasG12D, KrasG12D: Tp53) or doxycycline-inducible EGFR driven (EGFRT790M L858R or EGFR del19)30–32 lung tumors by ELISA (not shown). To study the potential role of IL-17A in lung pathogenesis mechanistically, we generated a conditional IL-17A allele, hereinafter referred to as IL-17, that contains the coding region of human IL-17A after the floxed stop codon. Stop cassette was removed by adenovirus carrying Cre recombinase43 to induce IL-17 expression. We crossed IL-17 mice with the conditional KrasG12D mutant mice and induced the expression of both IL-17 and KrasG12D (IL-17:Kras) in mice at 5–6 weeks of age by intranasal Adeno Cre delivery (Figure 1A, Supplementary Figure 1). We confirmed IL-17 expression by immunohistochemistry on formalin fixed tissue and by ELISA in BALFs (Figure 1B, C). IL-17:Kras mice had accelerated lung cancer evidenced by increased tumor burden (Figure 1B and D). Tumor cells in IL-17:Kras lungs had a significantly higher proliferation index as compared to Kras alone (Figure 1E), indicating that IL-17 promotes tumor cell growth in mice. Supporting the histological findings, longitudinal analysis revealed significantly reduced survival for IL-17:Kras compared to Kras (median survival 12 vs 23.2 weeks, p<0.0001) (Figure 1F). To examine the direct effect of human IL-17 on mouse tumor cells, we first confirmed that Kras mutant lung cancer cells expressed the receptor for IL-17A. IL-17 is recognized by the homo or hetero dimers of IL-17 receptor A(RA) and IL-17RC 44. Three independent cell lines derived from murine Kras driven lung tumors were found to express IL-17RA (Supplementary Figure 2A) and responded to both recombinant human and mouse IL-17A by producing IL-6 and granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF). This induction was dependent on IL-17RA; when IL-17RA was blocked with antibodies, IL-6 and G-CSF upregulation were impaired (Supplementary Figure 2B). Both IL-6 and G-CSF induction by recombinant IL-17A was also confirmed in human Kras driven lung cancer cell lines A549 and H1792 (Supplementary Figure 2C).

Figure 1. Expression of IL-17 in Kras mutant mice promotes lung cancer growth.

A) Breeding scheme for the IL-17 and Kras mice. B) Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining and IL-17 immunohistochemistry. Scale bars show: 1mm for the H&E panels and 50um for IL-17 IHC panels. C) Human IL-17A levels in the BAL fluid from the mice detected by ELISA. IL-17 (n=4), Kras (n=4) and IL-17:Kras (n=4). D) Total lung lesion counts for mice at 4 weeks (Kras:n=3, IL-17: Kras:n=4), 7 weeks (Kras:n=4, IL-17:Kras:n=4), and 12 weeks 4 weeks (Kras:n=6, IL-17:Kras:n=4) after Adeno-Cre induction. E) Top: Representative Ki67 immunohistochemistry and bottom: quantification of Ki67 staining. Scale bars show 50um for Ki67 panels. n=6 for Kras and n=5 for IL-17:Kras mice. 3 images have been quantified per mice.

F) Kaplan Meier Survival curve for the IL-17, Kras, and IL-17:Kras mice. Mice were added to the graph either when they died or reached disease burden euthanasia criteria. N=10, 16, 13 for IL-17, Kras, and IL-17:Kras mice. Median survival for Kras: 23.2 for IL-17:Kras 11.2 p<0.0001.

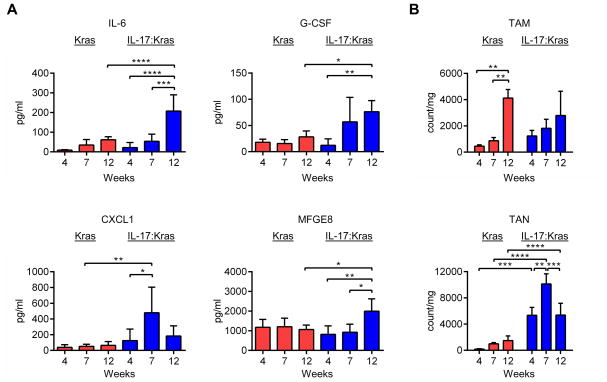

Elevation in IL-17 changes proinflammatory cytokine and cell profiles in Kras mutant lung tumors

IL-17 is an early proinflammatory cytokine that is responsible for initiating the inflammatory response by inducing the production of several other cytokines in the target cells 44. To understand how IL-17 affects the cytokine milieu in lungs, we measured the levels of cytokines with an ELISA. The proinflammatory cytokines IL-6, G-CSF, and MFG-E8, and chemokine CXCL1 were significantly elevated in the BALFs of IL-17:Kras mice as compared to Kras mice with the same disease burden (Supplementary Figure 3A, B-12 week timepoint). Time-course analysis of cytokines/chemokines revealed that as the tumors progressed, the proinflammatory cytokines were increased except for CXCL1, which peaked at week 7 (Figure 2A). To test whether the increase in the levels of proinflammatory cytokines and the patterns of cytokine elevation reflected the immune cell infiltration into the tumors, we analyzed the dynamics of immune cell types at 4, 7, and 12 weeks after tumor induction. These time points were determined based on the survival of double mutant mice. Correlating with the high levels of IL-6 and G-CSF, the counts of tumor associated neutrophils (TANs) were elevated in IL-17:Kras mice, making TANs the most dominant cell population. TAN counts were highest at 7 weeks after tumor induction (Figure 2B), correlating with CXCL1 production. CXCL1 can be produced by tumor cells as well as neutrophils themselves in a positive feedback loop 45, which may explain the observed pattern.

Figure 2. IL-17 modulates the lung cytokine and immune cell profiles.

A) Cytokine and chemokine (IL-6, G-CSF, CXCL1, and MFG-E8) analysis of BAL fluid at 4, 7, and 12 weeks in Kras and IL-17:Kras mice. n=4 at 4 weeks, n=4 at 7 weeks and n=5 at 12 weeks for Kras and IL-17:Kras mice both. B) Tumor associated macrophage (TAM) and tumor associated neutrophil (TAN) counts per mg of the lung tissue in Kras, IL-17:Kras mice. n=4 at 4 weeks, n=4 at 7 weeks and n=5 at 12 weeks for Kras and IL-17:Kras mice both.

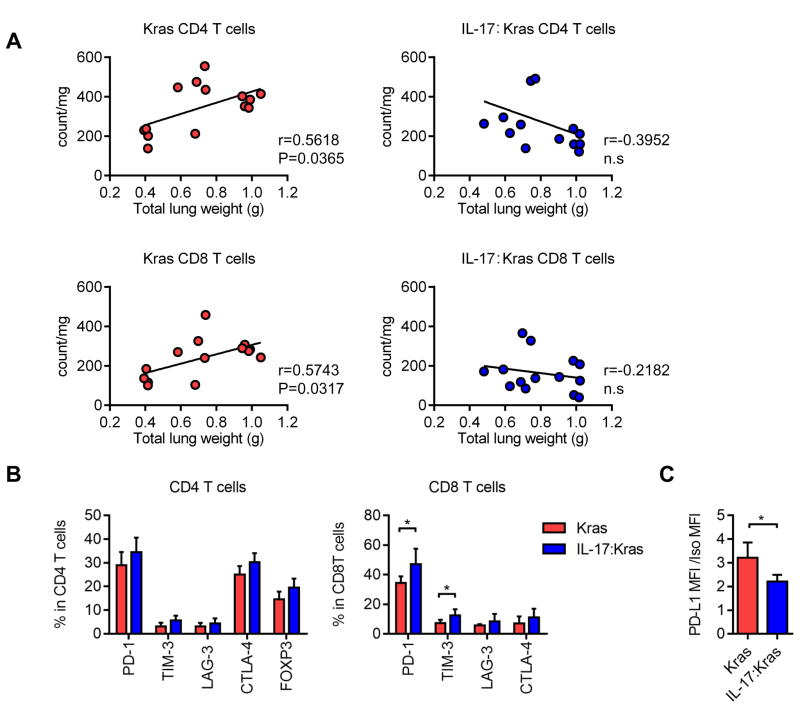

Neutrophil recruitment to tumors changes T cell counts and activation

Given the importance of adaptive immunity in suppressing growth of lung tumors, we next analyzed T cell counts and phenotypes in IL-17 expressing tumors. Analysis of tumor burden and CD8 and CD4 T cell counts in Kras and in IL-17:Kras mice revealed significant increases of CD4 and CD8 T cells with disease progression in Kras mutant mice. In contrast, IL-17:Kras mice did not show elevation but showed a trend towards decreased T cell counts with increased disease burden (Figure 3A). IL-17:Kras tumors had significantly fewer CD4 T cells, CD8 T cells, and B cells, and more TANs than Kras tumors at the same disease burden (lung weight) (Supplementary figure 3C). Counts of other cell types showed distinct patterns among Kras and IL-17:Kras mice at different time points. CD103 positive dendritic cell (CD103DC) counts were increased significantly between 4 and 12 weeks in Kras mice, while IL-17:Kras tumors showed significantly fewer CD103+DCs at 12 weeks compared to Kras tumors (Supplementary figure 4A). Eosinophil counts peaked at 7 weeks for Kras mutant tumors while other cell types did not show any significant changes (Supplementary figure 4A). We also performed direct correlations of counts of B and NK cells and disease burden. B cells counts and tumor burden had a significant positive correlation in Kras mice while IL-17:Kras mice did not show this trend. NK cell counts remained the same for Kras mice, while in IL-17:Kras mice they showed a negative correlation with disease burden (Supplementary figure 4B). These findings suggest that tumors do not have a static immune context and that cell composition is subject to change at different time points that correlate with changes in cytokines and chemokines.

Figure 3. T cell counts negatively correlate with disease burden in IL17 expressing mice and T cell express suppression markers.

A) Correlations of CD4 and CD8 T cell counts and total lung weights for Kras and IL-17:Kras mice. Kras:n=14, IL-17:Kras:n=14. B) Immune checkpoint receptor expression in CD4 and CD8 T cells from the Kras vs IL-17:Kras mice at the same tumor burden (Supplemental figure 3A, Kras:n=5 and IL-17:Kras:n=5). C) PD-L1 expression in the tumor cells from Kras vs IL-17:Kras mice at the same tumor burden (Supplemental figure 3A, Kras:n=5 and IL-17:Kras:n=5)

We also analyzed immune checkpoint receptor and ligand expression in the Kras and IL-17:Kras tumors at the same disease burden (Supplementary figure 3A). There was a significant increase in PD-1 and TIM-3 checkpoint receptor expression in the CD8 T cells of IL-17:Kras tumors at the 12-week time point (Figure 3B) as compared to Kras tumors. At this timepoint, tumor cell PD-L1 expression was significantly lower in the IL-17:Kras compared to Kras tumors (Figure 3C).

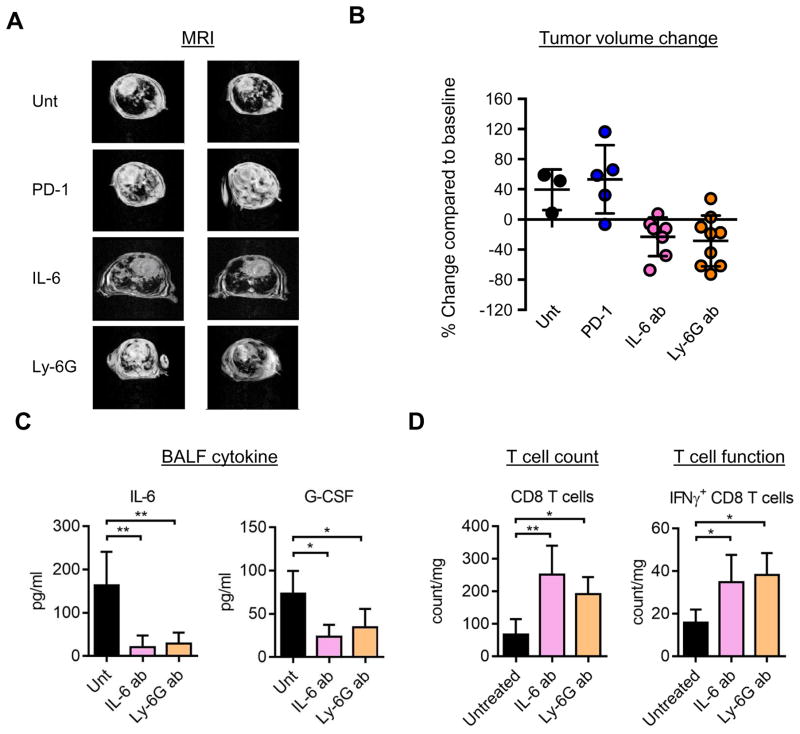

Neutrophil high IL-17:Kras tumors are resistant to immune-checkpoint blockade

Given that IL-6 is a tumor promoting cytokine and is involved in both recruiting tumor-promoting neutrophils 46 and driving tumor growth directly 47, we explored whether blockade of IL-6 or reducing neutrophil recruitment could inhibit tumor growth in our models. We treated IL-17:Kras mice with an IL-6 blocking antibody or a neutrophil depleting Ly-6G blocking antibody. IL-6 and Ly-6G blocking antibodies decreased the tumor burden significantly, as confirmed by MRI, at two weeks after treatment (Figure 4A and 4B; p=0.0086 and p=0.0107 for untreated vs IL-6 antibody and untreated vs Ly-6G antibody respectively). In contrast, tumors in IL-17:Kras mice did not respond to PD-1 blocking antibody (1A12) 37 (Figure 4A and Supplementary figure 5A). In longitudinal comparative studies, IL-17:Kras mice did significantly worse than Kras mice in response to PD-1 antibody (Supplementary Figure 5-mean response +24% vs +68% for Kras and IL-17:Kras respectively, n=10 for both groups, p=0.0005).

Figure 4. IL-17 high tumors are resistant to PD-1 immune checkpoint blockade but sensitive to IL-6 blockade or neutrophil depletion.

A) Left. Representative Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) images and Right: Quantification of MR images of mice untreated or treated with PD-1, IL-6 or Ly-6G blocking antibodies for 2 weeks. B) Quantification of MRI for treatments in A. Each data point represents a different mouse. C) Ki67 IHC on the lung tissue from IL-17:Kras mice either untreated or treated with IL-6 antibody, and quantification of IHC. p=0.02 for Ki67 counts between untreated and IL-6 antibody treated IL-17:Kras tumors. Each data point is from a different mouse lung tissue. D) Levels of IL-6 and G-CSF in the Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of IL-17:Kras mice untreated (n=4) or treated with IL-6 (n=5) or Ly-6G (n=5) antibodies for two weeks. E) CD8 T cell counts (left) and intracellular interferon gamma positive CD8 T cell counts per mg of lung for IL-17:Kras mice either untreated or treated with IL-6 or Ly-6G antibodies. Untreated (n=4), treated with anti-IL-6 treated:IL-6 ab (n=5) and anti-Ly-6G treated:Ly-6G ab (n=5).

To determine the mechanism of response to IL-6 or Ly-6G blocking antibodies, we analyzed the cytokines and T cells in mice treated with IL-6 or Ly-6G antibodies. Free IL-6 and G-CSF levels were reduced in the BALFs of treated mice (Figure 4C). There was also a significant increase in the total CD8 T cell counts, and an increase in CD8 T cells expressing interferon-gamma (IFN-g), a cytokine associated with T cell function (Figure 4D). Blocking IL-6 also led to a significant decrease in proliferation of the tumor cells (Supplementary Figure 5B and C). These data suggest expression of IL-17 is sufficient to change the immune microenvironment and that this change is dependent at least in part on IL-6 and immune suppressive neutrophils. Blocking either of these inhibitory pathways causes an enhanced anti-tumor immune response with increased T cell activation in the microenvironment, and suppression of tumor growth.

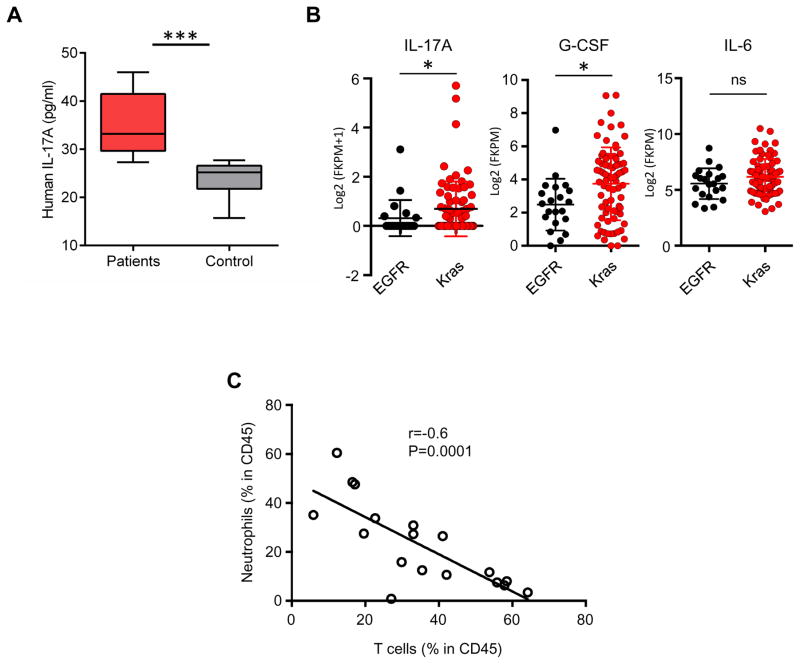

Kras mutant lung tumors express IL-17A, and Neutrophil counts are negatively correlated with T cell counts in patient NSCLC samples

To validate our preclinical findings, we first analyzed serum samples from lung cancer patients. Interestingly, serum samples from lung cancer patients had higher levels of IL-17A as compared to healthy controls (Figure 5A). Next, we studied the pro-inflammatory cytokines and myeloid cells in the context of non-small cell lung cancers with adenocarcinoma histology. In samples from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database1, KRAS mutant tumors, which are associated with smoking and inflammation displayed significantly higher levels of IL-17A and G-CSF as compared to EGFR mutant tumors (Figure 5B) (p=0.049 and 0.001, respectively). IL-6 levels were comparable in EGFR and KRAS mutant tumors, likely owing to the fact that IL-6 can be produced by several types of cells in the lung microenvironment 39. To further explore the relationship among neutrophils and T cells in human lung cancers, and the hypothesis that neutrophils limit anti-tumor T cell recruitment to tumor sites, we analyzed surgically resected NSCLC samples. As observed in the mouse studies, surgically resected patient lung tumors showed a significant negative correlation between the counts of tumor-associated neutrophils (CD45+ CD66b+) and T cells (CD45+ CD3+) or B cells (CD45+ CD19+) (shown as % of cells in total CD45+ cells) (r=−0.4333 p=0.0083 and r=−0.3699, p=0.0264, respectively calculated by linear regression analysis) (Figure 5C). Given the importance of T cell recruitment in lung tumor prognosis and response to checkpoint blockade treatments, identifying patients with high levels of neutrophil infiltration will be important to develop strategies to overcome barriers to anti-tumor T cell activity in the context of an immune microenvironment that is unlikely to be responsive to PD-1 blockade alone.

Figure 5. Lung cancer patients have increased serum IL-17. Increase in neutrophils is associated with decreased lymphocytes.

A) IL-17A levels in the sera of lung cancer patients and healthy controls n=10 for patients and 9 for control group. p=0.0003. B) Expression of IL17A, G-CSF (CSF3), and IL6 in EGFR and Kras mutant lung cancer samples from the TCGA dataset EGFR n=21, Kras n=75 samples 1. Expression of IL17A, CSF3, and IL6 were calculated from Log2 values of the RNA sequencing data. p=0.049, p=0.0103, and p=0.1546 for IL17A, G-CSF and IL-6 respectively. P values were calculated using Mann-Whitney test in graph-pad prism. C) Correlations of neutrophils (CD45+ CD66b+) vs T cells (CD45+ CD3+) in freshly resected patient NSCLC samples (Kras mutant) were calculated as % of immune cells in total CD45+ cells in all samples. p value was calculated by linear regression using graph-pad prism. n=35.

DISCUSSION

Our studies suggest that IL-17 is pro-tumorigenic by inducing the production of IL-6 and the recruitment of neutrophils in the tumor immune microenvironment. An increase in IL-17A is sufficient to change lung cytokine secretion and associated myeloid cell phenotypes, T cell function, and disease course. We found that the cytokine profile and myeloid cell counts changed over time, suggesting that tumor immune context is dynamic. Our findings support previous studies that showed a link between high neutrophil/T cell ratio in clinical samples and a poor prognosis of patients 48. Our studies suggest tumor associated neutrophils support lung cancer development and progression. Previous studies reported increased lung tumor metastasis with IL-17 expression in patients 49. We have not detected increased metastasis in this model, likely due to lack of additional tumor suppressor mutations, such as loss of Tp53 50.

Our analysis revealed an increase in circulating levels of IL-17A in human lung adenocarcinoma patients. We previously showed that mice compound deficient in granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), interleukin-3 (IL-3), and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) similarly develop a high incidence of lung adenocarcinomas within a background of chronic inflammation and infection 51. The IL-17 tumor promoting axis was activated in this lung carcinoma model.

We have previously demonstrated that oncogenic Kras:Lkb1 driven murine lung tumors are associated with a dense inflammatory infiltrate composed predominantly of neutrophils 39, and are resistant to PD-1 checkpoint blockade. Combined with this current study, these models suggest that the IL-17-neutrophil axis is important in lung cancer inflammation and in shaping the lung cancer immune microenvironment.

Response to PD-1 checkpoint blockade has been shown to be associated with PD-L1 expression, PD-1 positive T cell counts, or T cell presence in the tumor tissue 52. Previously we studied another mouse lung tumor model Kras:Lkb1 and showed that Lkb1 inactivation modulates the lung immune phenotype and promotes resistance to checkpoint blockade by inducing neutrophilic MDSCs 39. Our current study provides a unique example of oncogene/tumor suppressor mutation-independent phenotype associated with a single cytokine. Increased cytokine levels have been associated with resistance to targeted therapies. High IL-17 has been associated with resistance to VEGF inhibitors53, and IL-6 has been previously implicated in resistance to EGFR or MEK inhibitors 54, 55. Our findings suggest that IL-17 may also be a key molecule important in suppressing T cells and mediating resistance to PD-1 immune checkpoint blockade.

The primary role of IL-17 is to recruit and activate neutrophils during an infection 44, 56. IL-17 induces the production of proinflammatory cytokines from the stromal cells as well as tumor cells. We have shown that IL-17 induces IL-6 and G-GSF in lung tumor cells in the mouse, but the mechanism by which IL-17 is elevated in lung cancer patients remains unclear. Here we show that IL-17 contributes to lung tumor pathogenesis through coordinating a network of cellular and soluble factors that facilitate cell transformation and progression, while antagonizing protective anti-tumor lymphocyte cytotoxic function. These investigations will help identify novel host targets such as IL-17 itself or IL-17 induced chemokines or cytokines for cancer therapy, which may complement other efforts to develop lung cancer treatments based on tumor cell-intrinsic defects or activation of adaptive immunity against cancers by checkpoint blockade treatments. Future studies should focus on the mechanisms regulating the levels of cytokines such as genomic alterations, smoking history, and/or epigenetic modifications 57, and the impact of these mechanisms in mediating resistance to conventional chemotherapy and immunotherapies.

It remains to be determined whether the changes in the lung microenvironment of smokers also contribute to the increase in IL-17 and involve, at least in part, initiation of an infection response. Recent studies in an inflammatory colon cancer model suggests there are other sources of IL-17 such as γδT cells of the innate immune system that promote the chronic inflammatory state critical for infection-driven colon tumor development 58 and metastasis of breast tumors 17. Previous studies have also shown that nontypeable hemophilia influenza induces inflammation similar to chronic obstructive pulmonary (COPD) disease. It has been shown that this type of inflammation induced Th1 and Th17 cell recruitment in lung tumors in experimental systems 23. The microbiome of lung cancer patients may indeed be variable, causing differences in disease outcome and response to treatments, and may also possibly be associated with toxicities seen with immunotherapies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Harvard Medical School Rodent Pathology Core and Rod Bronson for tissue processing, Mei Zhang for immunohistochemistry, Dana-Farber flow cytometry core for help with flow cytometry, Kristen Labbe for administrative support, and Daryl Harmon for reading and editing the manuscript.

GRANT SUPPORT:

This work was supported by NIH/NCI P01 CA120964, 5R01CA163896-04, 1R01CA195740-01, 5R01CA140594-07, 5R01CA122794-10, and 5R01CA166480-04 grants to KK Wong. EA Akbay is supported by the International Association of the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) Young Investigator Award and the Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) Scholar Award RR160080. S. Koyama is supported by the Project for Cancer Research and Therapeutic Evolution (P-CREAT) from Japan Agency for Medical Research and development (AMED), the research grant of Mochida Foundation, Astellas Foundation and Suzuken Memorial Foundation. P.S.H. is supported by the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation, Starr Consortium for Cancer Research and NCI R01 CA 205150. GJ Freeman is supported by P50CA101942. P.S. Hammerman and K.K. Wong are supported by a Stand Up To Cancer - American Cancer Society Lung Cancer Dream Team Translational Research Grant (Grant Number: SU2CAACR-DT17-15). Stand Up To Cancer is a program of the Entertainment Industry Foundation. Research grants are administered by the American Association for Cancer Research, the scientific partner of SU2.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests:

GD is an employee of Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research and MJ is employee of MSD K.K. (subsidiary of Merck & Co in Tokyo Japan).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;511:543–550. doi: 10.1038/nature13385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Mello RA, Madureira P, Carvalho LS, et al. EGFR and KRAS mutations, and ALK fusions: current developments and personalized therapies for patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Pharmacogenomics. 2013;14:1765–1777. doi: 10.2217/pgs.13.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rekhtman N, Ang DC, Riely GJ, et al. KRAS mutations are associated with solid growth pattern and tumor-infiltrating leukocytes in lung adenocarcinoma. Modern pathology: an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 2013;26:1307–1319. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meng D, Yuan M, Li X, et al. Prognostic value of K-RAS mutations in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Lung cancer. 2013;81:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guan JL, Zhong WZ, An SJ, et al. KRAS mutation in patients with lung cancer: a predictor for poor prognosis but not for EGFR-TKIs or chemotherapy. Annals of surgical oncology. 2013;20:1381–1388. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2754-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takahashi H, Ogata H, Nishigaki R, et al. Tobacco smoke promotes lung tumorigenesis by triggering IKKbeta- and JNK1-dependent inflammation. Cancer cell. 2010;17:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ji H, Houghton AM, Mariani TJ, et al. K-ras activation generates an inflammatory response in lung tumors. Oncogene. 2006;25:2105–2112. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meylan E, Dooley AL, Feldser DM, et al. Requirement for NF-kappaB signalling in a mouse model of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2009;462:104–107. doi: 10.1038/nature08462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liao C, Yu Z, Guo W, et al. Prognostic value of circulating inflammatory factors in non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer biomarkers: section A of Disease markers. 2014;14:469–481. doi: 10.3233/CBM-140423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jafri SH, Shi R, Mills G. Advance lung cancer inflammation index (ALI) at diagnosis is a prognostic marker in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a retrospective review. BMC cancer. 2013;13:158. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomita M, Shimizu T, Ayabe T, et al. Elevated preoperative inflammatory markers based on neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and C-reactive protein predict poor survival in resected non-small cell lung cancer. Anticancer research. 2012;32:3535–3538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwakura Y, Ishigame H, Saijo S, et al. Functional specialization of interleukin-17 family members. Immunity. 2011;34:149–162. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lotti F, Jarrar AM, Pai RK, et al. Chemotherapy activates cancer-associated fibroblasts to maintain colorectal cancer-initiating cells by IL-17A. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2013;210:2851–2872. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma S, Cheng Q, Cai Y, et al. IL-17A produced by gammadelta T cells promotes tumor growth in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer research. 2014;74:1969–1982. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang K, Kim MK, Di Caro G, et al. Interleukin-17 receptor a signaling in transformed enterocytes promotes early colorectal tumorigenesis. Immunity. 2014;41:1052–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coffelt SB, Kersten K, Doornebal CW, et al. IL-17-producing gammadelta T cells and neutrophils conspire to promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2015;522:345–348. doi: 10.1038/nature14282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li L, Huang L, Vergis AL, et al. IL-17 produced by neutrophils regulates IFN-gamma-mediated neutrophil migration in mouse kidney ischemia-reperfusion injury. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2010;120:331–342. doi: 10.1172/JCI38702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colotta F, Allavena P, Sica A, et al. Cancer-related inflammation, the seventh hallmark of cancer: links to genetic instability. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1073–1081. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benchetrit F, Ciree A, Vives V, et al. Interleukin-17 inhibits tumor cell growth by means of a T-cell-dependent mechanism. Blood. 2002;99:2114–2121. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen X, Wan J, Liu J, et al. Increased IL-17-producing cells correlate with poor survival and lymphangiogenesis in NSCLC patients. Lung cancer. 2010;69:348–354. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu C, Hao K, Yu L, et al. Serum interleukin-17 as a diagnostic and prognostic marker for non-small cell lung cancer. Biomarkers: biochemical indicators of exposure, response, and susceptibility to chemicals. 2014;19:287–290. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2014.908954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang SH, Mirabolfathinejad SG, Katta H, et al. T helper 17 cells play a critical pathogenic role in lung cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:5664–5669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319051111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ji W, Choi CM, Rho JK, et al. Mechanisms of acquired resistance to EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitor in Korean patients with lung cancer. BMC cancer. 2013;13:606. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rothschild SI. Ceritinib-a second-generation ALK inhibitor overcoming resistance in ALK-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer. Translational lung cancer research. 2014;3:379–381. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2014.11.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2015;372:2018–2028. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patel SP, Kurzrock R. PD-L1 Expression as a Predictive Biomarker in Cancer Immunotherapy. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2015;14:847–856. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science. 2015;348:124–128. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herbst RS, Soria JC, Kowanetz M, et al. Predictive correlates of response to the anti-PD-L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature. 2014;515:563–567. doi: 10.1038/nature14011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ji H, Li D, Chen L, et al. The impact of human EGFR kinase domain mutations on lung tumorigenesis and in vivo sensitivity to EGFR-targeted therapies. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:485–495. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li D, Shimamura T, Ji H, et al. Bronchial and peripheral murine lung carcinomas induced by T790M-L858R mutant EGFR respond to HKI-272 and rapamycin combination therapy. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DuPage M, Dooley AL, Jacks T. Conditional mouse lung cancer models using adenoviral or lentiviral delivery of Cre recombinase. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1064–1072. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jackson EL, Willis N, Mercer K, et al. Analysis of lung tumor initiation and progression using conditional expression of oncogenic K-ras. Genes & development. 2001;15:3243–3248. doi: 10.1101/gad.943001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fisher GH, Wellen SL, Klimstra D, et al. Induction and apoptotic regression of lung adenocarcinomas by regulation of a K-Ras transgene in the presence and absence of tumor suppressor genes. Genes & development. 2001;15:3249–3262. doi: 10.1101/gad.947701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen Z, Sasaki T, Tan X, et al. Inhibition of ALK, PI3K/MEK, and HSP90 in murine lung adenocarcinoma induced by EML4-ALK fusion oncogene. Cancer research. 2010;70:9827–9836. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beard C, Hochedlinger K, Plath K, et al. Efficient method to generate single-copy transgenic mice by site-specific integration in embryonic stem cells. Genesis. 2006;44:23–28. doi: 10.1002/gene.20180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barber DL, Wherry EJ, Masopust D, et al. Restoring function in exhausted CD8 T cells during chronic viral infection. Nature. 2006;439:682–687. doi: 10.1038/nature04444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akbay EA, Pena CG, Ruder D, et al. Cooperation between p53 and the telomereprotecting shelterin component Pot1a in endometrial carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 2013;32:2211–2219. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koyama S, Akbay EA, Li YY, et al. STK11/LKB1 deficiency promotes neutrophil recruitment and proinflammatory cytokine production to suppress T cell activity in the lung tumor microenvironment. Cancer research. 2016 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akbay EA, Koyama S, Carretero J, et al. Activation of the PD-1 pathway contributes to immune escape in EGFR-driven lung tumors. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:1355–1363. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller DP, Liu G, De Vivo I, et al. Combinations of the variant genotypes of GSTP1, GSTM1, and p53 are associated with an increased lung cancer risk. Cancer research. 2002;62:2819–2823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koyama S, Akbay EA, Li YY, et al. Adaptive resistance to therapeutic PD-1 blockade is associated with upregulation of alternative immune checkpoints. Nature communications. 2016;7:10501. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tchaicha JH, Akbay EA, Altabef A, et al. Kinase domain activation of FGFR2 yields high-grade lung adenocarcinoma sensitive to a Pan-FGFR inhibitor in a mouse model of NSCLC. Cancer research. 2014;74:4676–4684. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miossec P, Kolls JK. Targeting IL-17 and TH17 cells in chronic inflammation. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2012;11:763–776. doi: 10.1038/nrd3794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fridlender ZG, Albelda SM. Tumor-associated neutrophils: friend or foe? Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:949–955. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fielding CA, McLoughlin RM, McLeod L, et al. IL-6 regulates neutrophil trafficking during acute inflammation via STAT3. Journal of immunology. 2008;181:2189–2195. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ancrile B, Lim KH, Counter CM. Oncogenic Ras-induced secretion of IL6 is required for tumorigenesis. Genes & development. 2007;21:1714–1719. doi: 10.1101/gad.1549407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takahashi Y, Kawamura M, Hato T, et al. Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio as a Prognostic Marker for Lung Adenocarcinoma After Complete Resection. World journal of surgery. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00268-015-3275-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li Q, Han Y, Fei G, et al. IL-17 promoted metastasis of non-small-cell lung cancer cells. Immunology letters. 2012;148:144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jackson EL, Olive KP, Tuveson DA, et al. The differential effects of mutant p53 alleles on advanced murine lung cancer. Cancer research. 2005;65:10280–10288. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dougan M, Li D, Neuberg D, et al. A dual role for the immune response in a mouse model of inflammation-associated lung cancer. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2011;121:2436–2446. doi: 10.1172/JCI44796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tumeh PC, Harview CL, Yearley JH, et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature. 2014;515:568–571. doi: 10.1038/nature13954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chung AS, Wu X, Zhuang G, et al. An interleukin-17-mediated paracrine network promotes tumor resistance to anti-angiogenic therapy. Nature medicine. 2013;19:1114–1123. doi: 10.1038/nm.3291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yao Z, Fenoglio S, Gao DC, et al. TGF-beta IL-6 axis mediates selective and adaptive mechanisms of resistance to molecular targeted therapy in lung cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:15535–15540. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009472107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lee HJ, Zhuang G, Cao Y, et al. Drug resistance via feedback activation of Stat3 in oncogene-addicted cancer cells. Cancer cell. 2014;26:207–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Taylor PR, Roy S, Leal SM, Jr, et al. Activation of neutrophils by autocrine IL-17A-IL-17RC interactions during fungal infection is regulated by IL-6, IL-23, RORgammat and dectin-2. Nature immunology. 2014;15:143–151. doi: 10.1038/ni.2797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Peng D, Kryczek I, Nagarsheth N, et al. Epigenetic silencing of TH1-type chemokines shapes tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nature. 2015;527:249–253. doi: 10.1038/nature15520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Housseau F, Wu S, Wick EC, et al. Redundant innate and adaptive sources of IL-17 production drive colon tumorigenesis. Cancer research. 2016 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.