Introduction

Lung abscess is a suppurative necrotizing collection occurring within the lung parenchyma. Symptoms of lung abscess include productive cough, fever, weight loss, putrid sputum and leukocytosis. Most lung abscesses are caused by mixed bacterial flora. Anaerobes are causative organism in 90% of lung abscesses, whereas aerobes often coexist in upto 50% of patients. Typically chest radiograph reveals a solitary cavitary lesion measuring around 4.0 cm in diameter with an air fluid level. Among the complications are progression to a chronic stage, empyema, hemoptysis, metastatic abscesses and bronchopleural fistula (BPF). Treatment of lung abscess is primarily medical consisting of an appropriate antibiotic regimen and chest physiotherapy. Surgery is reserved for unresponsive patients or those with complications. We report a case of lung abscess that ruptured into chest wall through a transpleural fistulous communication. This is a very rare event, which was diagnosed by imaging modalities and successfully treated by antibiotics. Interestingly this fistulous communication persisted even six months after treatment.

Case Report

A 22 year young soldier was admitted on 14 August 98' with history of high fever, cough and chest pain of 20 days duration. He noticed a swelling in left upper chest wall two days prior to admission. He was healthy until approximately 20 days prior to presentation, when he developed sudden onset high swinging fever with chills and drenching sweats. Simultaneously he developed cough with expectoration. Initially he had scanty mucopurulent expectoration but later about a week prior to admission he developed foul smelling expectoration 70–80 ml/day. Two days prior to admission he developed pleuritic pain and swelling in left upper chest wall near left anterior axillary fold. He complained of occasional shortness of breath at that time but denied any history of hemoptysis. He denied any significant past medical history. He also denied alcohol or illicit drug use. He had been a non-smoker. He was unmarried and was not exposed to commercial sexual workers.

Physical examination revealed an averagely built young man. There was no respiratory distress and he could lie down comfortably. There was no anaemia, cyanosis, or clubbing, and there were no distended veins, jugular venous pressure was not raised. BP 120/70 mm Hg (no pulsus paradoxus); pulse 96/min, respiratory rate 22/min. There was no hepatomegaly or edema of feet. Examination of chest showed trachea was shifted to right there was fullness of left supraclavicular, infraclavicular and axillary regions. A crepitus was appreciated on palpation of the swollen region. Percussion note was dull in left infraclavicular and axillary regions. Breath sounds were markedly diminished in intensity in the areas mentioned. Vocal fremitus and vocal resonance were decreased in these areas. Coarse crepitations and pleural rub were also heard in these regions. The heart sounds were normally heard with no gallop or murmur. Other systems were essentially normal.

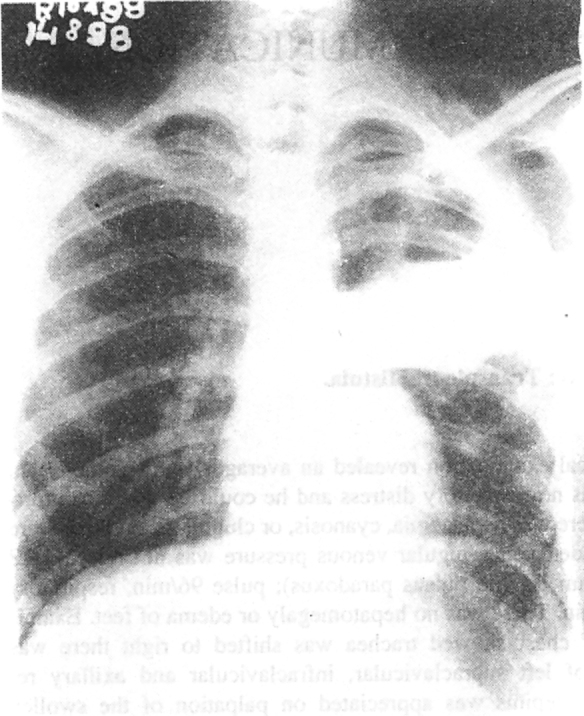

Investigations revealed a haemoglobin value of 9.1 gm/dl, a total leukocyte count of 16,400/cmm with polymorphonuclear leukocytosis (P-84%, L-12%, E-3%, and M-1%), and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 58mm/h (Wintrobe). Serum biochemistry values were normal. The chest radiograph showed a thick walled cavitary lesion in left upper and mid zones with a horizontal fluid level extending outside the bony cage and presence of air in soft tissues (Fig 1). The left costophrenic angle was not obliterated. The lateral radiograph showed dual air fluid level in the region of anterior segment of left upper lobe. A CT scan of chest revealed thick irregular walled cavitary lesion in anterior segment of left upper lobe extending and communicating with a chest wall abscess (Fig 2). Ultrasonography revealed an intrapulmonary well defined echogenic collection, which also contained air. In addition there was to and fro movement of air between chest wall abscess and lung abscess best appreciated during respiration and with probe pressure. Pleural collection was not appreciated. Sputum Gram stain revealed Gram positive cocci in short chains and bunches. Sputum smear was negative for acid fast bacilli and fungi. Culture of sputum grew Staphylococcus aureus. Needle aspirate of chest wall abscess also grew Staphylococcus aureus.

Fig. 1.

The chest radiograph posteroanterior view showing a thick walled cavitary lesion in left upper and mid zones with a horizontal fluid level extending outside the bony cage. An air fluid level is present in soft tissues. The left costophrenic angle is not obliterated

Fig. 2.

CT scan of chest showing thick irregular walled cavitary lesion in anterior segment of left upper lobe extending and communicating with a chest wall abscess. Multiple side pockets are demonstrable adjacent to main cavity.

The patient was treated with injectable penicillin, cloxacillin, metronidazole, and gentamicin alongwith postural drainage. He showed complete recovery with residual cystic lesion in left upper zone. He was sent on a spell of sick leave for six weeks. Review after sick leave showed persistence of cystic lesion in left upper zone. In addition the crepitus was also persisting in left infraclavicular region. This suggested a pocket of air in the chest wall having a communication with the lung. A CT thorax repeated at this stage confirmed presence of a residual cystic lesion in lung at the site of lung abscess and an air containing space in the chest wall at the site of initial chest wall abscess. These two spaces were communicating with each other through a fistulous tract (Fig 3). The pleural cavity did not contain air or fluid. This fistulous tract was delineated by fluroscopic guided injection of non-ionic contrast in the chest wall air-containing pocket and subsequent visualization of the intraparenchymal cyst alongwith connecting bronchi. Thus demonstrating a transpleural fistulous communication between lung abscess and the residual cavity in chest wall-a rare sequel of ruptured lung abscess.

Fig. 3.

A CT thorax showing a residual cystic lesion in lung and an air containing space in the chest wall. These two spaces are communicating with a chest wall abscess. Multiple side pockets are demonstrable adjacent to main cavity.

Discussion

This was a case of ruptured pyogenic lung abscess complicated by a transpleural fistulous communication with a chest wall abscess cavity, which was very well demonstrated by ultrasonography and CT scan of chest. Lung abscess associated with Staphylococcus aureus, gram-negative bacilli, and anaerobic bacteria from the oral cavity is not usually associated with upper-lobe lesions as in this case. He expectorated foul smelling sputum, suggesting that anaerobic bacteria were present in addition to Staphylococcus aureus which was cultured from sputum and needle aspirate. Mycobacterium tuberculosis has a predilection for the upper lobes, also such fistulae are more commonly seen with tuberculosis. But sputum AFB smear and Mycobacterium tuberculosis culture were negative in this case. Furthermore he improved with antibiotics without exhibiting antituberculosis drugs.

BPF had been recognized as a relatively common complication of lung abscess, especially in the pre-antibiotic era. However chest wall abscess is a very rare complication of lung abscess. Still rarer is the fistulous communication between lung abscess and chest wall without soiling the pleural cavity as in this case. This kind of persistent communication is probably not reported earlier to the best of our knowledge. BPF and empyema necessitatis are usually reported with tuberculosis [1, 2]. But suppurative lung infections due to anaerobic and pyogenic bacteria are usually diagnosed prior to extension through the chest wall. Diagnostic procedures should then be pursued, especially if a routine chest film suggests a fistula [3].

Sometimes it is very difficult to differentiate a peripheral lung abscess from a loculated pyopneumothorax with conventional radiography as happened in this case. Pathogenesis and presentation of both pleural empyema and lung abscess are indistinguishable especially so if air fluid level is present. Patients having BPF present with signs and symptoms of a hydro pneumothorax, dyspnea, chest pain, fever, and a change in sputum quantity and/or character. Typically, the expectorated material is thinner, yellower, and more plentiful in a certain body position, while less plentiful in others. Bronchography and a fistulogram were investigations of choice in earlier days for the diagnosis [2, 3]. In present case no such history of BPF was forthcoming and the clinico-radiological picture suggested a peripheral lung abscess or a loculated pyopneumothorax. Chest wall abscess with absent cough impulse and absent pleural reaction further confused the issue. We feel that the pleural inflammation sealed both visceral and parietal pleura, thus pus tracked directly out to the chest wall without soiling the pleural cavity. The pathogenesis of this transpleural fistula is same as of BPF, outcome may be a shade better in former since there is less risk of flooding the opposite healthy lung.

With newer modalities of radiological investigations like Ultrasonography and CT scan, it is now possible to differentiate between a peripheral lung abscess and loculated pyopneumothorax. With ultrasonic examination during hyperventilation, asymmetric motion of the proximal (chest wall-parietal pleura) and distal (visceral pleura-lung) interface occurs when the process is in pleural space. Whereas if the process is in lung parenchyma proximal and distal interfaces (anterior and posterior walls of the cavity) move symmetrically [4]. CT scan of chest is the preferred method in differentiating pyopneumothorax from lung abscess [5]. With CT scanning, a pyopneumothorax is characterised by unequal fluid levels on positional scanning. The space has a smooth regular margin that is sharply defined without side pockets. Appearance of cavity often changes with variations in patient's position. In contrast, a lung abscess is typically round with irregular, thick wall and has an air fluid level of equal length in all positions. When patient's position is changed, the shape of the cavity and of the mass do not change. Frequently, multiple side pockets are demonstrable adjacent to main cavity (Fig. 2). Also large empyema displaces adjacent lung whereas lung abscess does not [5]. Sometimes above criteria are insufficient to make such a distinction whence contrast enhanced CT is often useful. Demonstration of vessel within a lesion is usually seen in parenchymal rather than in pleural lesion. Most lung abscesses enhance whereas most pleural lesions show minimal or no enhancement [6].

Bronchopleural fistula is best managed by preventing it altogether. It has become less prevalent with advances in chemotherapy and improvement in surgical techniques. In contrast to the benefits of surgery seen with BPF, the role of surgery is uncertain in the management of a pleurocutaneous fistula [7]. Poulos et al demonstrated Klebsiella pneumoniae right lower lobe lung abscess which dissected through the chest wall to produce a subcutaneous mass, producing a dome shaped lesion above the right hemidiaphragm on chest radiograph that resolved immediately with surgical drainage [8]. The present case was managed conservatively with antibiotics without any surgical intervention. Surgery probably could have obliterated the persistent transpleural fistulous tract.

REFERENCES

- 1.Iseman MD, Madsen LA. Chronic tuberculous empyema with bronchopleural fistula resulting in treatment failure and progressive drug resistance. Chest. 1991;100:124–127. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.1.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson TM, McCann W, Davey WN. Tuberculous bronchopleural fistula. AM Rev Respir Dis. 1973;107:30–41. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1973.107.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woodruff W. The recognition and treatment of bronchopleural fistula. Am J Surg. 1941;54:236–251. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adams FV, Kolodny E. M-mode ultrasonic localisation and identification of fluid containing pulmonary cysts. Chest. 1979;75:330–333. doi: 10.1378/chest.75.3.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pugatch RD, Spirn PW. Radiology of the pleura. Clin Chest Med. 1985;6:17–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bressler EL, Francis IR, Glazer GM, Gross BH. Bolus contrast medium enhancement for distinguishing pleural from parenchymal lung disease CT features. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1987;11:436–440. doi: 10.1097/00004728-198705000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butt AA, Pankey GA, Figuero JE. A drainage chest wall abscess. Infect Med. 1997;14(12):935–938. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poulos J, Johnson SR, Conrad P, Montero J, Vesely DL. Dome-shaped lesion on chest radiograph: retroperitoneal abscess dissecting through the posterior chest wall. South Med J. 1994;87(1):77–80. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199401000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]