Abstract

Two novel oxazole-thiazole containing cyclic hexapeptides, bistratamides M (1) and N (2) have been isolated from the marine ascidian Lissoclinum bistratum (L. bistratum) collected in Raja Ampat (Papua Bar, Indonesia). The planar structure of 1 and 2 was assigned on the basis of extensive 1D and 2D NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry. The absolute configuration of the amino acid residues in 1 and 2 was determined by the application of the Marfey’s and advanced Marfey’s methods after ozonolysis followed by acid-catalyzed hydrolysis. The interaction between zinc (II) and the naturally known bistratamide K (3), a cyclic hexapeptide isolated from a different specimen of Lissoclinum bistratum, was monitored by 1H and 13C NMR. The results obtained are consistent with the proposal that these peptides are biosynthesized for binding to metal ions. Compounds 1 and 2 display moderate cytotoxicity against four human tumor cell lines with GI50 values in the micromolar range.

Keywords: cytotoxic, sponge, Lissoclinum bistratum, cyclic hexapeptides, bistratamides, Zn complex

1. Introduction

Ascidians of the genus Lissoclinum are a rich source of cyclic peptides, many of which incorporate modified amino acid residues containing thiazole, oxazole, thiazoline, or oxazoline rings. Examples reported in the literature include the hexapeptides bistratamides A–J [1,2,3], cycloxazoline [4] (also known as westiellamide) [5], the heptapeptides nairaiamides A and B [6], and lissoclinamides 4 and 5 [7], and the octapeptides patellamides A–C [8] and tawicyclamides A and B [9].

The symbiotic microbial origin of the cyclic peptides isolated from specimens of the genus Lissoclinum has been proposed based on the fact that similar structures have been discovered from cyanobacteria [10]. Ascidians harbor an obligate symbiont, Prochloron sp., a cyanobacterium that photosynthesizes nutrients for the sea squirt, which is thought to be involved in the biosynthesis of the cyclic peptides as secondary metabolites [11]. This hypothesis has been confirmed for the case of the patellamides [12] and an efficient method for the in vivo production of this type of cyclic peptide has also been described [13].

Some of these azole-based cyclic peptides and their synthetic derivatives have shown antibacterial, antiviral, or cytotoxic activities, along with metal binding properties. In fact, the concentration of metal ions such as Cu2+ and Zn2+ in ascidian cells has been found to reach values over 104 times those detected in the surrounding sea water [14]. The necessary structural and stereochemical features to facilitate metal complexation along with the biological relevance of the metal ions and their possible role in the assembly of cyclic peptides in the marine environment have been proposed [15]. Moreover, the former biological activities could be attributable to the conformational constraints imposed by the heterocycles and their ability to bind metals or intercalate into DNA. Particularly, the antitumor activities and the potential to act as metal ion chelators have made these azole-based cyclic peptides attractive targets for total synthesis and biological evaluation [16].

As part of our ongoing efforts to find novel antitumor agents from marine organisms and specifically from ascidians [17,18], a detailed biological investigation of a specimen of L. bistratum collected by hand off the coast of Raja Ampat Islands, Indonesia, showed that its organic extract displayed cytotoxic activity against the human tumor cell lines A-549 (lung), HT-29 (colon), MDA-MB-231 (breast) and PSN1 (pancreas). Bioassay-guided fractionation of the active organic extract resulted in the isolation of two new cyclic hexapeptides, bistratamides M (1) and N (2), which show significant cytotoxicity towards different human cancer cells.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Isolation and Structure Elucidation

A specimen of the marine ascidian L. bistratum was extracted several times using CH2Cl2/MeOH (1:1). The extract was subsequently fractionated by vacuum flash chromatography (VFC) on a Lichoprep RP-18 column using a gradient mixture of H2O, MeOH and CH2Cl2 with decreasing polarity. Bioassay-guided isolation using the previously described human tumour cell lines yielded a very active fraction (eluted with 100% MeOH) that was subjected to reversed-phase HPLC to yield 1 and 2 (Figure 1).

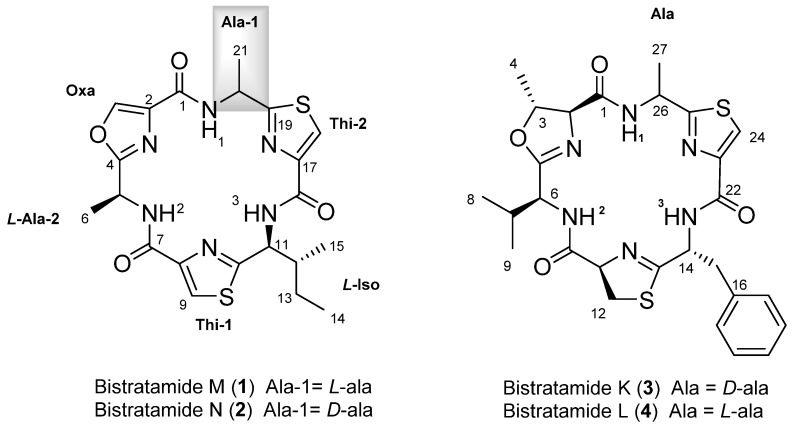

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of compounds 1–4.

Bistratamide M (1) was obtained as a colourless amorphous solid with a molecular formula C21H24N6O4S2 (13 degrees of unsaturation) determined by the [M + H]+ ion peak at m/z 489.1405, detected in its (+)-HRESI-TOFMS. The hexapeptide structure of 1 was suggested by the six nitrogen atoms present in its molecular formula along with the six sp2 carbon signals between δC 159.4 and 171.6 observed in its 13C NMR spectrum (Table 1). The presence of only three amide NH signals at δH 8.42, 8.64, and 8.69, along with three singlet aromatic protons at δH 8.12, 8.22, and 8.27, observed in the 1H NMR spectrum of 1, suggested the existence of three cyclically-modified amino acids.

Table 1.

NMR data of 1 and 2 in CDCl3 (500 MHz for 1H and 125 MHz for 13C).

| No. | Bistratamide M (1) | Bistratamide N (2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| δC, Type | δH Mult, (J in Hz) | δC, Type | δH Mult, (J in Hz) | |

| 1 | 159.7, C | - | 159.0, C | - |

| 2 | 135.5, C | - | 135.6, C | - |

| 3 | 141.9, CH | 8.27, s | 141.5, CH | 8.23, s |

| 4 | 164.3, C | - | 164.6, C | - |

| 5 | 44.2, CH | 5.38, m | 44.1, CH | 5.37, m |

| 6 | 19.9, CH3 | 1.72, d (7.1) | 20.8, CH3 | 1.72, d (6.8) |

| 7 | 159.4, C | - | 159.5, C | - |

| 8 | 149.2, C | - | 149.1, C | - |

| 9 | 123.0, CH | 8.12, s | 123.3, CH | 8.12, s |

| 10 | 167.1, C | - | 167.9, C | - |

| 11 | 55.3, CH | 5.44, m | 54.9, CH | 5.54, m |

| 12 | 40.1, CH | 2.18, m | 41.5, CH | 2.09, m |

| 13 | 26.3, CH2 | 1.63, m; 1.24, m | 25.6, CH2 | 1.67, m; 1.32, m |

| 14 | 11.5, CH3 | 1.01, t (7.4) | 11.6, CH3 | 1.02, t (7.4) |

| 15 | 14.5, CH3 | 0.87, d (6.8) | 15.1, CH3 | 0.97, d (6.8) |

| 16 | 159.8, C | - | 159.8, C | - |

| 17 | 148.2, C | - | 148.6, C | - |

| 18 | 125.0, CH | 8.22, s | 124.3, CH | 8.17, s |

| 19 | 171.6, C | - | 171.0, C | - |

| 20 | 48.2, CH | 5.40, m | 47.7, CH | 5.46, m |

| 21 | 23.9, CH3 | 1.74, d (6.9) | 24.8, CH3 | 1.75, d (6.7) |

| NH-1 | - | 8.69, d (5.7) | - | 8.71, d (6.5) |

| NH-2 | - | 8.64, d (7.2) | - | 8.65, d (7.3) |

| NH-3 | - | 8.42, d (8.0) | - | 8.46, d (9.0) |

2D NMR experiments of 1, including COSY, TOCSY, and edited HSQC, allowed us to identify their amino acid residues. Thus, the diagnostic methyl groups at δH 1.72 (d, 7.1)/δC 19.9 and δH 1.74 (d, 6.9)/δC 23.9 were indicative of the presence of two alanines, while the spin system δH 8.42 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, NH), 5.44 (m, 1H)/2.18 (m, 1H)/1.63, 1.24 (m, 2H)/1.01 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H), and 0.87 (d, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H) showed the existence of an isoleucine residue. Additionally, the proton and carbon NMR aromatic signals at δH 8.12 (s, 1H)/δC 123.0 and at δH 8.22 (s, 1H)/δC 125.0 suggested the occurrence of two thiazole rings while those at δH 8.27 (s, 1H)/δC 141.9 indicated the existence of an oxazole moiety. These rings are the result of the condensation of two cysteines and one serine residue, respectively (Table 1). The former assignments accounted for 12 of the 13 unsaturation degrees required by the molecular formula, so the cyclic nature of this hexapeptide was deduced from the remaining unsaturation.

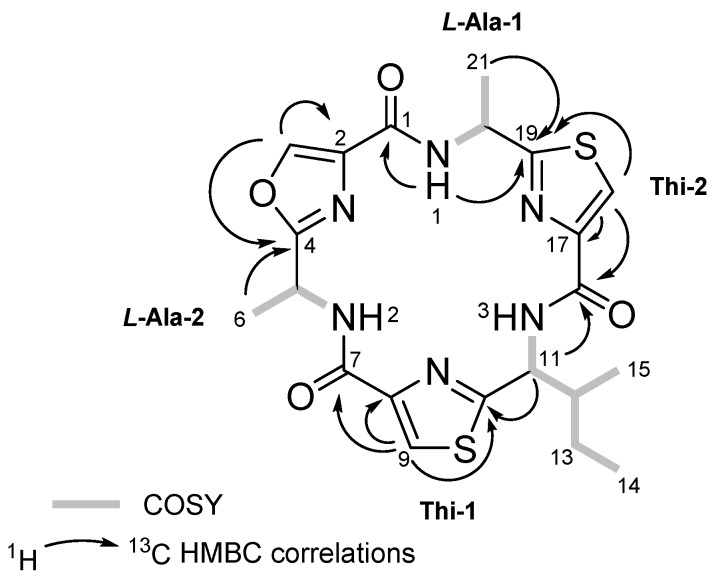

The long range proton and carbon correlations observed in the HMBC experiment of 1 from each of the amide NH protons allowed to us to establish not only the amino acid sequence of this cyclic peptide but also to confirm the presence of the thiazole and oxazole rings. Thus, the HMBC correlations from the alanine amide NH proton at δH 8.69 (NH-1) to C-19 at δC 171.6, corresponding to the thiazole-2 ring, and to carbonyl C-1 at δC 159.7, corresponding to the oxazole ring, allowed us to locate the first alanine residue (Ala-1) between the thiazole (Thi-2) and oxazole rings. The location of the isoleucine residue between the two thiazole rings was deduced from the long range correlations from its α-proton at δH 5.44 (H-11) to C-10 at δC 167.1 and to C-16 at δH 159.8, assigned to the thiazole-1 and thiazole-2 aromatic rings, respectively. Finally, the HMBC correlation between the oxazole aromatic proton at δH 8.27 (H-3) to C-2 at δC 135.5 and to C-4 at δC 164.3 of the oxazole ring and this in turn to H-6 at δH 1.72 of the second alanine established the link between Ala-2 and the oxazole ring (Figure 2). Following the established nomenclature used for the family of cyclic hexapeptides isolated from L. bistratum, compound 1 was named as bistratamide M.

Figure 2.

COSY correlations (displayed by bold bonds) and key HMBC (arrows) in 1 and 2.

To complete the structure of 1, the absolute configuration of the amino acids was established via acid hydrolysis of the product obtained by ozonolysis of 1 followed by derivatization with Marfey’s reagent and posterior analysis by HPLC. Thus, the HPLC analysis of l-FDAA (Marfey’s method) for the alanines [19] and l-FDAA and d-FDAA derivatives for the isoleucine (advanced Marfey’s method) [20,21] showed that 1 contains two l-alanine and one l-isoleucine residues.

Bistratamide N (2) was obtained as colourless amorphous solid. Its molecular formula, C21H24N6O4S2, determined by (+)-HRESI-TOFMS, proved to be the same as 1. Moreover, the proton and carbon NMR chemical shifts of both compounds were very similar, suggesting that 2 contained the same residues but different stereochemistry for at least one of the amino acid residues. Analysis of the HMBC data of 2, showing similar HMBC correlations to those of 1, displayed the same amino acid sequence as in its isomer 1. Indeed, the long range correlations between the first alanine methyl protons at δH 1.75 (H-21) to C-19 at δC 171.0 and this in turn to the aromatic proton at δC 8.17 (H-18) of the thiazole (Thi-2) linked the first alaline residue to the thiazole ring. The HMBC correlations from the isoleucine α-proton at δH 5.54 (H-11) to C-16 (δC 159.8) and C-10 (δC 167.9) confirmed the location of the isoleucine between the two thiazole rings. Additionally, HMBC correlations from the oxazole aromatic proton at δH 8.23 (H-3) to C-2 (δC 135.6) and C-4 (δC 164.6) and this, in turn, to H-6 (δH 1.72), of the second alanine, completed the sequence assignment. The absolute configuration of 2 was obtained in a similar way as for 1. Compound 2 was submitted to ozonolysis, followed by acid hydrolysis and derivatization with Marfey’s reagent l-FDAA (Marfey’s method) for the alanines, and l-FDAA and d-FDAA for the isoleucine (advanced Marfeýs method). HPLC-MS analysis of the resulting derivatives showed the presence of l- and d-alanine and l-isoleucine. Thus, an additional problem in this case was to establish the exact position of each alanine residue in compound 2. Taking into account that acid hydrolysis of this type of cyclic peptides, using 6N HCl at 110 °C, means that the oxazole rings will be cleaved whilst the thiazole rings remain intact, compound 2 was subjected to these hydrolytic conditions [22]. HPLC separation of the resulting acid hydrolysates followed by analysis using Marfey’s method showed the presence of l-alanine instead of d-alanine. Consequently, we deduced that the alanine residue linked to the oxazole ring has the L configuration, while the alanine linked to the thiazole ring in 2 must have the D configuration.

The proton and chemical shifts of bistratamides M and N (1 and 2) are similar to those of the reported for dolastatin E which was isolated from the sea hare Dolabella auricularia. They differ in one of the heterocycle rings: the second thiazole ring (Thi-2) in 1 and 2 is replaced by a thiazoline moiety in dolastatin E. However, the absolute stereochemistry of the aminoacid residues in dolastatin E was not determined [23].

2.2. Interaction Studies of Zinc (II) with Bistratamide K

The extremely low level of biologically-available essential metals in the marine environment suggests that marine organisms have developed unique mechanisms for their acquisition, retention, and utilization. Little is known about these mechanisms, but it has been suggested that secondary metabolites may play a vital role. Many marine secondary metabolites contain functional groups that can complex metals, but there is a lack of evidence as to whether this occurs in vivo [24]. Furthermore, an improved understanding of the role of metal ions is required not only for studying the mechanism of enzymatic catalysis by metalloenzymes, but also because transition metal ions play an important role in pathophysiological processes and the perturbation of zinc-finger binding. As such, small peptides such as the bistratamides are very useful model compounds for the study of complex formation.

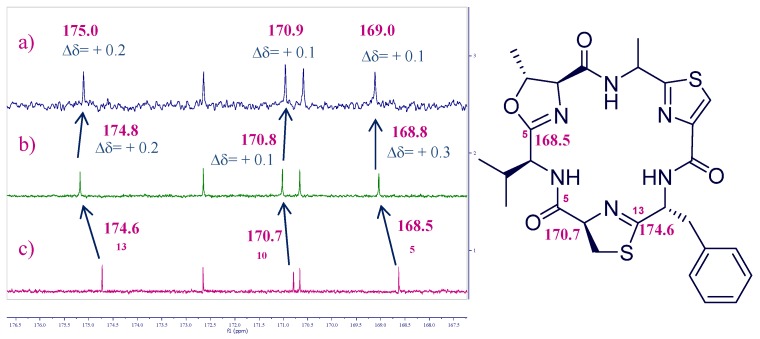

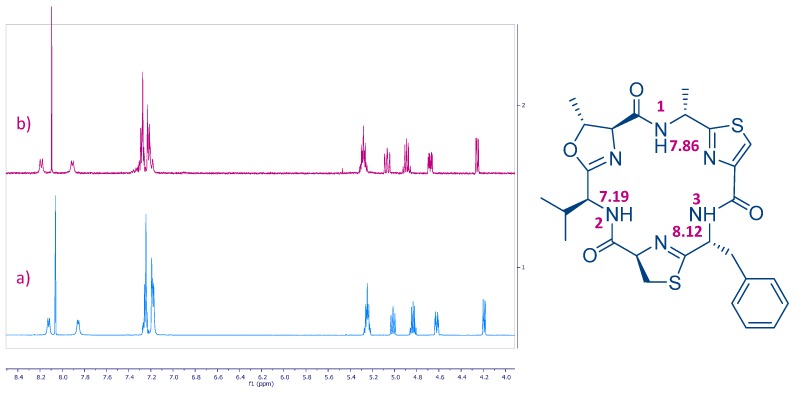

Azole-based cyclic peptides found in ascidians of the genus Lissoclinum have a high propensity to chelate metal ions. Although there are many studies on metal binding of azole-based cyclic octapeptides, those related to cyclic hexapeptides [25,26] are less common [27]. In order to study the chelating properties of this type of oxazole-thiazole cyclic hexapeptides, we focused our attention on bistratamide K (3), also isolated by our research group at PharmaMar in a reasonable amount along with its l-alanine isomer, bistratamide L (4) (Figure 1), from another specimen of Lissoclinum of the same expedition [28]. Initial trials of the interactions of copper (II) and lithium with 3 were unsuccessful. However, interesting results were obtained when we tested the interaction of Zn (II) with 3. The Zn (II)-binding behaviour of 3 was studied in CD3CN by adding a ZnCl2 solution to a solution of the peptide in a NMR tube and analysis of the resulting 13C and 1H NMR spectra. Spectral changes were observed in the carbon chemical shifts of the 13C NMR spectra of 3 after addition of 2 and 4 equivalents of ZnCl2. The downfield carbon chemical shifts at positions C-5 (δC 168.5), C-10 (δC 170.7) and C-13 (δC 174.6) suggested that these positions are involved in the zinc binding of 3 (Figure 3). However, no changes were observed in the corresponding 1H NMR spectrum (Figure 4), which seems to indicate that none of the amide nitrogen atoms is bound to the metal (the corresponding NH proton chemical shift signals neither moved nor disappeared).

Figure 3.

Partial 13C NMR spectra of compound 3 after addition of a ZnCl2 solution: (a) 4 equiv.; (b) 2 equiv.; and (c) 0 equiv. in CD3CN.

Figure 4.

Partial 1H NMR spectra of (a) compound 3 and (b) after addition of a 4 equiv. ZnCl2 solution in CD3CN.

This result contrasts to that obtained by Comba et al. in the coordination studies of Cu2+ ions with westiellamide, a similar cyclic hexapeptide, and three synthetic analogues [29]. Their corresponding mononuclear complexes showed Nhet-Namide-Nhet binding sites and each Cu2+ ion was coordinated by three nitrogen atoms of the macrocycle, two of the nitrogen donors originating from azole rings and the third one from an NH amide group. The coordination sphere was completed by solvent molecules. In our case, deprotonation of the amide nitrogen donor is not observed and so, the Zn2+ ion is not coordinated by an amide nitrogen atom. The changes seen in positions C-5, C-10, and C-13 are in agreement with the studies carried out with Gahan et al., whereby the K+ complex of the cyclic octapeptide ascidiacyclamide showed that the potassium ion was bound to the two nitrogen atoms of the thiazole rings and to the oxygen center of the adjacent amide groups [30].

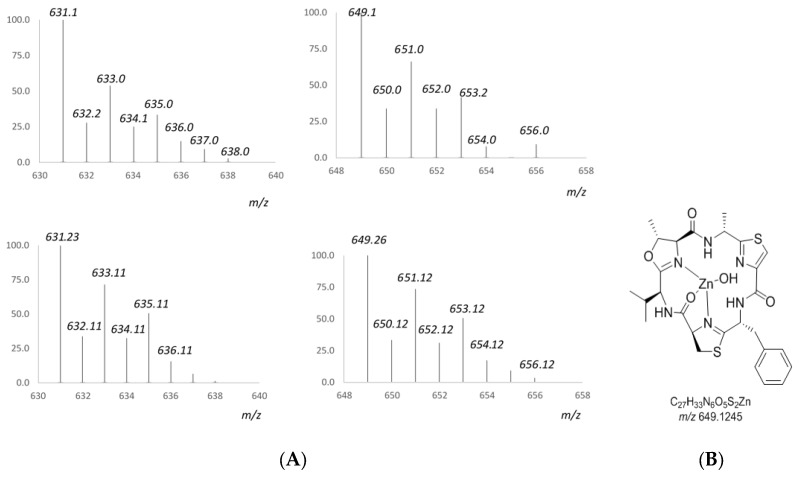

A further study of the zinc complex of 3 by mass spectrometry was carried out in order to ascertain its structure. Analysis of isotope patterns were employed to assign the components of the complex. The main cluster ions detected in the (+)-ESI-TOF mass spectrum of 3 (see Supplementary Materials) after addition of 4 equiv. of Zn2+ along with the corresponding calculated isotopic patterns are displayed in Figure 5. Thus, the ion cluster observed at m/z 649 was assigned to a mononuclear Zn2+ complex of 3 which is further coordinated to an OH group. The loss of 18 units, giving the ion cluster detected at m/z 631 as the base peak, could be due to the loss of a molecule of water.

Figure 5.

(A) Experimental (top) and calculated (bottom) isotopic clusters of compound 3 after addition of a 4 equiv. ZnCl2 solution detected in its (+)-ESI-TOFMS. (B) Structure proposal for a mononuclear Zn2+ complex of 3.

Cell proliferation assays against the human tumor cell lines MDA-MB-231 (breast), HT-29 (colon), NSLC A-549 (lung), and PSN1 (pancreas), and showed that both 1 and 2 exhibit moderate cytotoxic activity with GI50 values in the micromolar range (Table 2). As a positive standard the antitumor compound doxorubicin was also tested in parallel following an identical procedure and the results are included in Table 2. These cytotoxic activity values are similar to those reported for cyclic hexapeptides bistratamides E–J. Interestingly, it has been found that cyclic peptides containing two thiazole rings instead of one thiazole and one oxazole ring display higher activity [3,31]. In order to get some insights into the mechanism of action of the cytotoxic activity of these compounds, a further study was performed. Compounds 1 and 2 were tested in the enzymatic Topoisomerase 1 (Top1) assay using human recombinant enzyme as described in the experimental section, and failed to show any hint of inhibition even at the highest concentration tested (100 μM).

Table 2.

Cytotoxic activity data (μM) of 1 and 2.

| Compound | Cell Line | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast | Colon | Lung | Pancreas | ||

| MDA-MB-231 | HT-29 | NSLC A-549 | PSN1 | ||

| Bistratamide M (1) | GI50 | 18 | 16.0 | 9.1 | 9.8 |

| TGI | >20.0 | >20.0 | >20.0 | >20.0 | |

| LC50 | >20.0 | >20.0 | >20.0 | >20.0 | |

| Bistratamide N (2) | GI50 | >20.0 | 13.0 | 11.0 | 15.0 |

| TGI | >20.0 | >20 | >20.0 | >20.0 | |

| LC50 | >20.0 | >20 | >20.0 | >20.0 | |

| Doxorubicin | GI50 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| TGI | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.5 | |

| LC50 | 2.4 | >17.2 | >17.2 | 3.1 | |

GI50, compound concentration that produces 50% inhibition on cell growth as compared to control cells; TGI, compound concentration that produces total growth inhibition as compared to control cells, and LC50, compound concentration that produces 50% cell death as compared to control cells.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Experimental Procedures

Optical rotations were determined using a Jasco P-1020 polarimeter (Oklahoma City, OK, USA). UV spectra were performed using an Agilent 8453 UV-VIS spectrometer (Santa Clara, CA, USA). IR spectra were obtained with a Perkin-Elmer Spectrum 100 FT-IR spectrometer (Waltham, MA, USA) with ATR sampling. NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian “Unity 500” spectrometer (Palo Alto, CA, USA) at 500/125 MHz (1H/13C). Chemical shifts were reported in ppm using residual CDCl3 (δ 7.26 ppm for 1H and 77.0 ppm for 13C) and CD3CN (δ 1.96 ppm for 1H, and 118.3 and 1.8 ppm for 13C) as an internal reference. (+)-ESIMS were recorded using an Agilent 1100 Series LC/MSD spectrometer. High-resolution mass spectroscopy (HRMS) was performed with an Agilent 6230 TOF LC/MS system using the ESI-MS technique.

3.2. Animal Material

The ascidian Lissoclinum bistratum was collected by hand and traditional scuba diving in Raja Ampat Islands (Papua Bar, Indonesia) (00° 33.353′ S/130° 41.156′ E) at depths ranging between 1 and 8 m in April 2007 and frozen immediately after collection. A voucher specimen (ORMA48136) is deposited at PharmaMar.

3.3. Extraction and Isolation

A specimen of Lissoclinum bistratum (75 g) was triturated and exhaustively extracted with CH3OH:CH2Cl2 (50:50, 3 × 500 mL). The combined extracts were concentrated to yield a crude mass of 2.6 g that was subjected to VLC on Lichroprep RP-18 (Merck KGaA, Kenilworth, NJ, USA) with a stepped gradient from H2O to CH3OH and then CH2Cl2. The fraction eluting with CH3OH (351 mg) was subjected to semi-preparative HPLC (Waters XBridge C18, 5 μm, 10 × 150 mm, gradient from 33 to 73% CH3CN in H2O with 0.1% TFA in 20 min, flow: 5 mL/min, UV detection, Milford, MA, USA) to yield 1 (6 mg, retention time: 15.1 min) and 2 (3.4 mg, retention time: 9.5 min).

Bistratamide M (1): Compound 1 was isolated as an amorphous, colorless solid; [α] −40.2 (c 1.4, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax 202 nm; IR (ATR) νmax 3396, 2969, 2932, 1678, 1604, 1496, 1208, 1142, 845, 802, 726 cm−1; 1H NMR (500 MHz) and 13C NMR (125 MHz) see Table 1; (+)-HRESI-TOFMS m/z 489.1405 [M + H]+ (calcd. for C21H25N6O4S2, m/z 489.1373).

Bistratamide N (2): Compound 2 was isolated as an amorphous, colorless solid; [α] −9.6 (c 1.1, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax 202 nm; IR (ATR) νmax 3395, 2969, 2932, 1678, 1604, 1541, 1496, 1208, 1143, 845, 803, 726 cm−1; 1H NMR (500 MHz) and 13C NMR (125 MHz) see Table 1; (+)-HRESI-TOFMS m/z 489.1383 [M + H]+ (calcd. for C21H25N6O4S2, m/z 489.1373).

3.4. Absolute Configuration

Bistratamides M (1) (0.2 mg, 0.4 mmoL) and N (2) (0.2 mg, 0.4 mmoL) were dissolved in dry CH2Cl2 (3 mL), and a stream of ozone in oxygen was bubbled through each solution for 5 min. After solvent removal under vacuum, the resulting crude products were hydrolyzed in 0.5 mL of 6 N HCl at 110 °C for 18 h. Excess aqueous HCl was removed under a N2 stream and 100 μL of H2O, 0.4 mg of 1-fluoro-2,4-dinitrophenyl-5-l-alaninamide (l-FDAA, Marfey’s reagent) in 100 μL of acetone and 1 M NaHCO3 (40 μL) was added to the dry hydrolysates. The resulting mixtures were heated at 40 °C for 1 h. Then, the reaction mixtures were cooled to 23 °C, quenched by addition of 2 N HCl (100 μL), dried, and dissolved in H2O (660 μL). Each aliquot was then subjected to reversed-phase LC/MS (column: Waters Symmetry, 150 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm; mobile phase, CH3CN + 0.04% TFA/H2O + 0.04% TFA; flow rate, 0.8 mL/min) using a linear gradient (20–50% CH3CN over 30 min). The retention times and ESIMS product ions (tR in min, m/z [M + H]+) of the l-FDAA mono-derivatized amino acids in the hydrolysates of 1 and 2 were established as l-Ala (14.1, 342.2) in 1 and l-Ala (14.3, 342.2) and d-Ala (16.8, 342.2) in 2.

Advanced Marfey’s analysis of isoleucine standard: To 0.3 mg (2.2 mmoL) of a 1:1 mixture of l-Ile and d-allo-Ile standards (Sigma I2877) was added a 1:1 racemic mixture of 0.2 mg of 1-fluoro-2,4-dinitrophenyl-5-l-alaninamide (l-FDAA) in 50 μL of acetone, 0.2 mg of 1-fluoro-2,4-dinitrophenyl-5-d-alaninamide (d-FDAA) in 50 μL of acetone, and 1 M NaHCO3 (40 μL), and the mixture was heated at 40 °C for 1 h. After that time, the mixtures were cooled to 23 °C, quenched by addition of 2 N HCl (100 μL), dried, and dissolved in H2O (660 μL) to obtain the four stereoisomers of isoleucine. Analysis of the retention times of the derivatized amino acids (tR in min), using LC (Phenomenex Lux Cellulose-4 column, 250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm, 100 Å; mobile phase, CH3CN containing 0.1% TFA; flow rate, 1 mL/min using an isocratic gradient (35% CH3CN over 50 min)), were l-FDAA-l-Ile (33.9), l-FDAA-d-allo-Ile (36.0), d-FDAA-l-Ile (31.4) (equivalent to l-FDAA-d-Ile), and d-FDAA-d-allo-Ile, (27.9) (equivalent to l-FDAA-l-allo-Ile). Comparison of tR of the Ile unit in the hydrolysates of 1 and 2 (33.9) with the l/d-FDAA-derivatized amino acid standards, showed the configuration of Ile to be L in both cases.

3.5. Titration of Bistratamide K (3)

Three milligrams of Bistratamide K was dissolved in CD3CN (0.75 mL) and titrated by adding 0.2 by 0.2 equiv. of ZnCl2 in CD3CN until reaching a total of 4 equiv. NMR experiments were carried out after each 0.2 equiv. were added.

3.6. Biological Assays

The cytotoxic activity of compounds 1 and 2 was tested against NSLC A-549 human lung carcinoma cells, MDA-MB-231 human breast adenocarcinoma cells, HT-29 human colorectal carcinoma cells, and PSN1 (human pancreatic carcinoma cells). The concentration giving 50% inhibition of cell growth (GI50) was calculated according to the procedure described in the literature [32]. Cell survival was estimated using the National Cancer Institute (NCI) algorithm [33]. Three dose response parameters were calculated for 1 and 2.

The activity of human topoisomerase I was determined based on the increase in fluorescence of a commercial dye (“H19”, Profoldin, Westborough, MA, USA) when interacting with DNA and the higher number of interaction points present in supercoiled DNA with respect to relaxed DNA. Therefore, the activity of the enzyme causes a decrease of fluorescence intensity when the probe is added. The enzyme reaction is performed in a final volume of 20 μL in 384 black wells. Compounds 1 and 2, at twice their final concentrations, were mixed with 50 pM recombinant human topoisomerase I (Profoldin, Westborough, MA, USA) in 10 μL of 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0 with 150 mM sodium chloride, 3 mM magnesium chloride and 5% (v/v) glycerol and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Then, reaction was started by the addition of 10 μL of supercoiled DNA (Profoldin, Westborough, MA, USA) at 25 μg/mL in the same buffer and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Finally, the reaction was stopped by the addition of 30 μL of H19 dye in its commercial buffer to reach the dye concentration recommended by the vendor. After 1 h at room temperature the degree of conversion from supercoiled to relaxed DNA was determined by monitoring fluorescence intensity (excitation at 485 nm, emission at 535 nm) in a microtiter plate reader. Final compound concentration covered a range from 100 to 0.2 μM following 10 serials of 1:2 dilutions. IC50 values were calculated by fitting the results to a typical four parameters logistic curve by nonlinear regression analysis.

4. Conclusions

In summary, we have isolated two novel cyclic hexapeptides from the ascidian Lissoclinum bistratum, and bistratamides M (1) and N (2). NMR and MS analysis and Marfey’s method were used for the determination of their planar structures and absolute configurations and they are characterized by the presence of oxazole and thiazole rings. These cyclic peptides showed moderate cytotoxic activity against four human tumor cell lines. In addition, a study of the interaction of Zn2+ with another cyclic hexapeptide, bistratamide K (3), isolated from the same organism indicated the formation of a mononuclear Zn2+complex of 3 as shown by NMR and confirmed by ESI-TOFMS experiments. These results help provide further understanding of the relationships between metals and the azole-based cyclic peptides found in ascidians [29].

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the help of our PharmaMar colleagues, Elena Gomez for her excellent technical assistance, Carlos de Eguilior and Santiago Bueno for collecting the marine samples, Juan M Dominguez for the design of the biological assays, and Simon Munt for revision of the manuscript. We also thank Xavier Turón, CEAB (Centro de Estudios Avanzados de Blanes, Spain) for determining taxonomy. We also acknowledge Ardimis Arban, Edison Munaf, Abdi Dharma, and the University of Andalas for the Research Collaboration Agreement for the collection of the samples in Indonesia. The present research was partially supported by grant RTC-2016-4611-1 from Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at www.mdpi.com/1660-3397/15/7/209/s1, Figures S1–S26: NMR spectra of bistratamides M, N, and K; Figure S27: Key HMBC of bistratamide K; Figures S28–S31: Analysis by Marfey’s method; Figures S32 and S33: NMR spectra data of bistratamide K after addition of ZnCl2 solutions; Figure S34: (+)-ESI-TOFMS of bistratamide K after addition of 4 equiv. ZnCl2 solution; Table S1: NMR data of bistratamides M, N, and K.

Author Contributions

Carlos Urda contributed to the extraction, isolation, identification and Marfey’s experiments. Rogelio Fernández performed the NMR experiments and contributed to the elucidation of the structures. Jaime Rodríguez and Carlos Jiménez conceived the studies on the coordination of zinc (II), analyzed the data, and prepared part of the manuscript. Marta Pérez revised and corrected the data and Carmen Cuevas revised the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Degnan B.M., Hawkins C.J., Lavin M.F., McCaffrey E.J., Parry D.L., Watters D.J. Novel Cytotoxic Compounds from the Ascidian Lissoclinum bistratum. J. Med. Chem. 1989;32:1354–1359. doi: 10.1021/jm00126a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mark P.F., Gisela P.C., Gina B.C., Ireland C.M. Bistratamides C and D. Two new oxazole-containing cyclic hexapeptides isolated from a Philippine Lissoclinum bistratum ascidian. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:6671–6675. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perez L.J., Faulkner D.J. Bistratamides E–J, Modified Cyclic Hexapeptides from the Philippines Ascidian Lissoclinum bistratum. J. Nat. Prod. 2003;66:247–250. doi: 10.1021/np0204601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hambley T.W., Hawkins C.J., Lavin M.F., Van den Brenk A., Watters D.J. Cycloxazoline: A cytotoxic cyclic hexapeptide from the ascidian Lissoclinum bistratum. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:341–348. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4020(01)88146-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prinsep M.R., Moore R.E., Levine I.A., Patterson G.M. Westiellamide, a bistratamide-related cyclic peptide from the blue-green alga Westiellopsis prolifica. J. Nat. Prod. 1992;55:140–142. doi: 10.1021/np50079a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foster M.P., Ireland C.M. Nairaiamides A and B. Two Novel Di-Proline Heptapeptides Isolated from a Fijian Lissoclinum bistratum Ascidian. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:2871–2874. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)60468-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmitz F.J., Ksebati M.B., Chang J.S., Wang J.L., Hossain M.B., van der Helm D., Engel M.H., Serban A., Silfer J.A. Cyclic Peptides from the Ascidian Lissoclinurn patella: Conformational Analysis of Patellamide D by X-ray Analysis and Molecular Modeling. J. Org. Chem. 1989;54:3463–3472. doi: 10.1021/jo00275a036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ireland C.M., Durso A.R., Newman R.A., Hacker M.P. Antineoplastic Cyclic Peptides from the Marine Tunicate Lissoclinurn patella. J. Org. Chem. 1982;47:1807–1811. doi: 10.1021/jo00349a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDonald L.A., Foster M.P., Phillips D.R., Ireland C.M. Tawicyclamides A and B, New Cyclic Peptides from the Ascidian Lissoclinum patella: Studies on the Solution- and Solid-state Conformation. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:4616–4624. doi: 10.1021/jo00043a017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crawford J.M., Clardy J. Bacterial symbionts and natural products. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:7559–7566. doi: 10.1039/c1cc11574j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewin R., Chang L. Prochloron: A Microbial Enigma. Chapman and Hall; New York, NY, USA: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Milne B.F., Long P.F., Starcevic A., Hranueli D., Jaspars M. Spontaneity in the patellamide biosynthetic pathway. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2006;4:631–638. doi: 10.1039/b515938e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Houssen W.E., Bent A.F., McEwan A.R., Pieiller N., Tabudravu J., Koehnke J., Mann G., Adaba R.I., Thomas L., Hawas U.W., et al. An Efficient Method for the In Vitro Production of Azol(in)e-Based Cyclic Peptides. Angew. Chem. 2014;53:14171–14174. doi: 10.1002/anie.201408082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Comba P., Dovalil N., Gahan L.R., Hanson G.R., Westphal M. Cyclic peptide marine metabolites and CuII. Dalton Trans. 2014;43:1935–1956. doi: 10.1039/C3DT52664J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bertram A., Pattenden G. Marine metabolites: Metal binding and metal complexes of azole-based cyclic peptides of marine origin. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2007;24:18–30. doi: 10.1039/b612600f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bertram A., Maulucci N., New O.M., Mohd Nor S.M., Pattenden G. Synthesis of libraries of thiazole, oxazole and imidazole-based cyclic peptides from azole-based amino acids. A new synthetic approach to bistratamides and didmolamides. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007;5:1541–1553. doi: 10.1039/b701999h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia A., Lenis L.A., Jiménez C., Debitus C., Quiñoá E., Riguera R. The Occurrence of the Human Glycoconjugate C2-α-d-Mannosylpyranosyl-l-tryptophan in Marine Ascidians. Org. Lett. 2000;2:2765–2767. doi: 10.1021/ol0061384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiménez C., Quiñoá E., Castedo L., Riguera R. Epidioxy Sterols from the Tunicates Dendrodoa grossularia and Ascidiella aspersa and the Gastropoda Aplysia depilans and Aplysia punctata. J. Nat. Prod. 1986;49:905–909. doi: 10.1021/np50047a023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marfey P. Determination of d-amino acids. II. Use of a bifunctional reagent, 1,5-difluoro-2,4-dinitrobenzene. Carlsberg Res. Commun. 1984;49:591–596. doi: 10.1007/BF02908688. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harada K., Fujii K., Hayashi K., Suzuki M., Ikai Y., Oka H. Application of d,l-FDLA derivatization to determination of absolute configuration of constituent amino acids in peptide by advanced Marfey’s method. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:3001–3004. doi: 10.1016/0040-4039(96)00484-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Urda C., Pérez M., Rodríguez J., Jiménez C., Cuevas C., Fernández R. Pembamide, a N-methylated linear peptide from a sponge Cribrochalina sp. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016;57:3239–3242. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2016.05.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banker R., Carmeli S. Tenuecyclamides A–D, Cyclic Hexapeptides from the Cyanobacterium Nostoc spongiaeforme var. tenue. J. Nat. Prod. 1998;61:1248–1251. doi: 10.1021/np980138j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ojika M., Nemoto T., Nakamura M., Yamada K. Dolastatin E, a new cyclic hexapeptide isolated from the sea hare Dolabella auricularia . Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:5057–5058. doi: 10.1016/00404-0399(50)0922Y-. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Michael J.P., Pattenden G. Marine Metabolites and Metal Ion Chelation: The Facts and the Fantasies. Angew. Chem. 1993;32:1–23. doi: 10.1002/anie.199300013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ngyen H., Orlamuender M., Pretzel D., Agricola I., Sternberg U., Reissmann S. Transition metal complexes of a cyclic pseudo hexapeptide: Synthesis, complex formation and catalytic activities. J. Pept. Sci. 2008;14:1010–1021. doi: 10.1002/psc.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Comba P., Eisenschmidt A., Gahan L.R., Hanson G.R., Mehrkens N., Westphal M. Dinuclear ZnII and mixed CuII–ZnII complexes of artificial patellamides as phosphatase models. Dalton Trans. 2016;45:18931–18945. doi: 10.1039/C6DT03787A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Comba P., Dovalil N., Haberhauer G., Hanson G.R., Kato Y., Taura T.J. Complex formation and stability of westiellamide derivatives with copper (II) Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2010;15:1129–1135. doi: 10.1007/s00775-010-0673-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Urda C., Gómez E., Reyes F., García-Cerezo A., Tanaka J., de Eguilior C., Bueno S., Cuevas C. Bistratamides K-N, Four New Thiazole-containing Cyclic Hexapeptides from the Ascidian Lissoclinum bistratum; Proceedings of 14th Symposium on Marine Natural Product/8th European Conference on Marine Natural Products, La Toja Island; Galicia, Spain. 15–20 September 2013; p. 184/p. 249. The 1D (1H and 13C NMR) and 2D (COSY, HSQC, HMBC) NMR spectra of bistratamide K (3) along with its proton and carbon chemical shifts data and a figure displaying the key HMBC correlations are enclosed in the supporting material. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Comba P., Gahan L.R., Haberhauer G., Hanson G.R., Noble C.J., Seibold B., van den Brenk A.L. Copper (II) Coordination Chemistry of Westiellamide and Its Imidazole, Oxazole, and Thiazole Analogues. Chem. A Eur. J. 2008;14:4393–4403. doi: 10.1002/chem.200701778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van den Brenk A.L., Fairlie D.P., Gahan L.R., Hanson G.R., Hambley T.W. A novel potassium-binding hydrolysis product of ascidiacyclamide: A cyclic octapeptide isolated from the ascidian Lissoclinum patelIa. Inorg. Chem. 1996;35:1095–1110. doi: 10.1021/ic9504755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grøndahl L., Sokolenko N., Abbenante G., Fairlie D.P., Hanson G.R., Gahan L.R. Interaction of zinc (II) with the cyclic octapeptides, cyclo[Ile(Oxn)-d-Val(Thz)]2 and ascidiacyclamide, a cyclic peptide from Lissoclinum patella. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1999:1227–1234. doi: 10.1039/a808836e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skehan P., Storeng R., Scudiero D., Monks A., McMahon J., Vistica D., Warren J.T., Bokesch H., Kenney S., Boyd M.R. New Colorimetric Cytotoxicity Assay for Anticancer-Drug Screening. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1990;82:1107–1112. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.13.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shoemaker R.H. The NCI60 human tumour cell line anticancer drug screen. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:813–823. doi: 10.1038/nrc1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.