Abstract

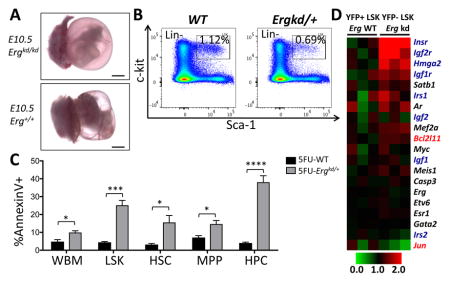

ERG, an ETS family transcription factor frequently overexpressed in human leukemia, has been implicated as a key regulator of hematopoietic stem cells. However, how ERG controls normal hematopoiesis, particularly at the stem and progenitor cell level, and how it contributes to leukemogenesis remain incompletely understood. Using homologous recombination, we generated an Erg knockdown allele (Ergkd) in which Erg expression can be conditionally restored by Cre recombinase. Ergkd/kd animals die at E10.5–E11.5 due to defects in endothelial and hematopoietic cells, but can be completely rescued by Tie2-Cre-mediated restoration of Erg in these cells. In Ergkd/+ mice, ~40% reduction in Erg dosage perturbs both fetal liver and bone marrow hematopoiesis by reducing the numbers of Lin−Sca-1+c-Kit+ (LSK) hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) and megakaryocytic progenitors. By genetic mosaic analysis, we find that Erg-restored HSPCs outcompete Ergkd/+ HSPCs for contribution to adult hematopoiesis in vivo. This defect is in part due to increased apoptosis of HSPCs with reduced Erg dosage, a phenotype that becomes more drastic during 5-FU-induced stress hematopoiesis. Expression analysis reveals that reduced Erg expression leads to changes in expression of a subset of ERG target genes involved in regulating survival of HSPCs, including increased expression of a pro-apoptotic regulator Bcl2l11 (Bim) and reduced expression of Jun. Collectively, our data demonstrate that ERG controls survival of HSPCs, a property that may be utilized by leukemic cells.

Keywords: Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), Transcription factors, Apoptosis, Leukemia, Hematopoietic progenitors, Animal Models

Graphical Abstract

Loss of Erg impairs fetal hematopoiesis (A; Scale bars = 1mm). Its reduced expression in adults leads to reduction in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell (HSPC) number (B), in part due to impaired survival of HSPCs, particularly during stress hematopoiesis (C; P values: *p≤0.05; ***p≤0.005; ****p≤0.001). At the molecular level, reduced Erg expression in HSPCs leads to upregulation of Bcl2l11 and IGF/insulin signaling-related genes, as well as downregulation of Jun (D).

Introduction

ERG is an ETS family transcription factor (TF) frequently involved in human cancers, including leukemia 1, prostate cancer 2 and Ewing’s sarcoma 3, 4. It functions as an oncogene through chromosomal translocations or overexpression. In human leukemia, ERG was initially thought to play a role in leukemogenesis based on the t(16;21) translocation in acute myeloid leukemia (AML), leading to formation of the FUS (TLS)-ERG fusion 5. In some cases of AML with this translocation, the leukemia exhibits features of acute megakaryoblastic leukemia 6. Besides aberrant expression due to chromosomal translocation, high levels of ERG are often observed in leukemias with adverse outcome. In AML with complex karyotypes, which confers a very poor prognosis 7, ERG is often overexpressed due to gene amplification 8. In lymphocytic leukemia, high expression of ERG in adult T-acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) also predicts adverse outcome 9. In addition to AML with chromosomal translocations and complex karyotypes, ~45% of AML patients have a normal karyotype without chromosomal aberrations [i.e., cytogenetically normal AML (CN-AML)] 10. In CN-AML cases, high ERG expression levels also correlate strongly with poor prognosis 10. Strikingly, CN-AML patients with both high ERG transcript levels and an FLT3-ITD (internal tandem duplications) have extremely poor prognoses, comparable to patients with AML displaying complex karyotypes 10. Taken together, these clinical data suggest that elevated ERG expression may play a significant role in leukemogenesis and contribute to an adverse prognosis. In animal models, forced expression of ERG in fetal hematopoietic progenitors promotes megakaryopoiesis and ERG alone acts as a potent oncogene in vivo leading to rapid onset of leukemia in mice 11. Overexpression of ERG in bone marrow (BM) hematopoietic progenitors induces development of lymphoid and erythro-megakaryocytic leukemia 12, 13. Transgenic expression of ERG also causes T-ALL in mice 14.

To study the role of ERG in hematopoiesis, a potential loss-of-function Erg mutant allele was generated through a forward-genetic approach (ENU mutagenesis) 15. Characterization of mice carrying this mutant allele (ErgMld2) displayed profound defects in definitive hematopoiesis, megakaryopoiesis, and hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) number in ErgMld2/+ adults 15. More recently, a conditional knockout allele of Erg revealed that ERG promotes the maintenance of HSCs by restricting their differentiation 16. However, the extent to which ERG employs any additional mechanisms to regulate hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) is uncertain. Here we describe an Erg knockdown allele (Ergkd) created by knockin of a floxed Stopper cassette into the Erg locus. This allele is also conditional for full rescue as excision of the Stopper restores Erg gene function. Analysis of this engineered mouse reveals a previously unappreciated role of ERG in maintaining survival of HSPCs.

Materials and Methods

Mice

The Ergkd allele was generated by conventional gene targeting procedures in CJ7 mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells. Correctly targeted ES clones were screened and confirmed by Southern blot analysis (Fig. S1A), and were injected into mouse blastocysts. Mx1-Cre 17, Tie2-Cre 18, Sox2-Cre 19, and Rosa26-L-S-L-YFP (R26Y) 20 mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (JAX). All animal procedures and protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Boston Children’s Hospital.

RT–PCR analysis

RNA was isolated from the indicated cell types and cDNA was synthesized using the iScript RT-PCR Kit (Bio-Rad, Berkeley, CA). For quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR), the QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) was used using a BioRad iCycler. Expression was calculated using the ΔCT method relative to GAPDH level.

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed and Western blot analysis was performed as described 21. Western blots were probed with Erg C-17 antibody (Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX) and anti-β-Actin antibody (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was used as a loading control.

Histology

Embryos and embryonic tissues were fixed in Bouin’s fixative or in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) using standard protocols. Whole-mount immunohistochemistry staining for yolk sacs using anti-PECAM monoclonal antibody MEC13.3 (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA) was performed as described 22.

Complete blood count (CBC)

Blood was collected with EDTA-coated capillaries (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) from adult mice by retro-orbital sinus bleeding. CBC was performed as described 23.

Flow cytometric analysis

BM, peripheral blood (PB), and fetal liver (FL) single cell suspensions were prepared and flow cytometry was performed as described 23, 24, using an Accuri C6 (BD Biosciences) or DXP11 analyzer (Cytek, Fremont, CA), or the FACSAria sorter as well. Sorting was performed using a FACSAria sorter (BD Biosciences). The following antibodies were used: CD41-FITC, Sca-1-FITC, Ter119-PE, CD45-PE, CD150-PE, Sca-1-PE, and c-kit-APC, as well as biotinylated B220, Mac-1, Gr-1, Ter-119, CD3e [i.e., lineage markers for BM, or for FL (without Mac-1)]; CD45, CD31, Ter119 (i.e., lineage markers for non-hematopoietic tissues), followed by streptavidin-PerCPCy5.5, Sca-1-APCcy7, c-kit-BV711, CD150-PE, CD48-APC. All antibodies were from eBioscience (San Diego, CA) or BD Pharmingen.

Apoptosis analysis

BM single cell suspensions were prepared and flow cytometry was performed as described 23, 24, using a FACSAria sorter (BD Biosciences). Cells were stained with AnnexinV-PEcy7 first. After washing, cells were stained with biotinylated lineage markers. After another washing, cells were stained with streptavidin-PerCP, Sca1-APCcy7, c-kit-BV711, CD150-PE, CD48-APC. After washing, cells were suspended in PBS with DAPI and subjected to flow cytometry analysis. For CD34/flt3 staining, after AnnexinV-PEcy7 staining, cells were washed and stained with CD34-eFluor660 and Flt3-PE first, followed by staining of lineage and streptavidin-PerCP, Sca1-APCcy7, c-kit-BV711.

Colony-forming assays

FL and BM colony forming assays in methylcellulose (MethoCult M3434, Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Megakaryocytic colony assays were performed using collagen-based medium (MegaCult, Stemcell Technologies) in the presence of 20 ng/ml TPO (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ).

Microarray Analyses

RNA was extracted using RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen). Samples were submitted to Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Microarray Core Facility for amplification, cDNA and cRNA synthesis and hybridization with Affymetrix MOE430_2 chips. The data were processed and analyzed as described 21 and have been deposited to Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession# GSE48600.

Statistical analysis

Student’s t-test was used. Data were reported as Mean ± S.E.M.

Results

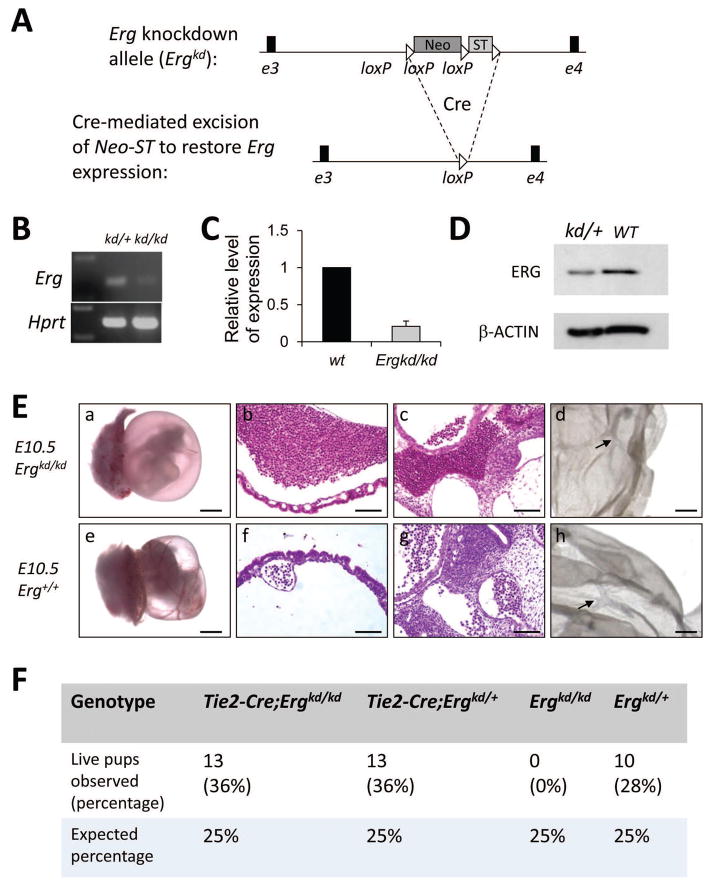

A novel Erg knockdown allele leads to ~80% reduction in Erg expression

We utilized a reverse-genetic approach to disrupt Erg expression by generating a knockdown allele (Ergkd) in which a floxed transcriptional Stopper cassette (ST), together with a Neomycin (Neo)-resistant cassette 21, was inserted in the intron between exons 3 and 4 of the Erg gene (Figs. 1A and S1A) 25. The insertion greatly impairs Erg expression. In yolk sac-derived hematopoietic cells from homozygous knockdown animals (Ergkd/kd), only trace amounts of Erg transcripts were detected by RT-PCR (Fig. 1B); qRT-PCR analysis of Erg transcripts from day-10 embryoid bodies (EBs) differentiated from Ergkd/kd ES cells demonstrated ~80% reduction in Erg transcripts, compared to wild type (WT) cells (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, we confirmed reduced ERG protein level in Ergkd/+ bone marrow (BM) cells by Western blot (Fig. 1D), indicating that Ergkd is a hypomorphic allele of Erg.

Figure 1. ERG plays essential roles in hematopoietic and endothelial cells during development.

(A) Schematic diagram showing design of the Ergkd allele. Cre-mediated excision of the floxed Neo-ST cassette (ST: transcriptional stopper) knocked-in to the Ergkd allele can lead to its restoration to WT Erg. (B) RT-PCR showing dramatic reduction in Erg transcripts in yolk sac-derived hematopoietic cells from Ergkd/kd embryos in comparison to Ergkd/+ embryos. Hprt expression level was used as the loading control. Note the Ergkd/kd (kd/kd) sample was slightly overloaded to show residual Erg transcript expressed from the Ergkd allele. (C) qRT-PCR showing ~80% reduction in Erg transcripts in day-10 EBs from Ergkd/kd ES cells compared to those from WT ES cells. (D) Western blot showing reduced ERG expression at the protein level in Ergkd/+ versus WT bone marrow cells; β-actin expression was used as the loading control. (E) E10.5 Ergkd/kd embryos (a) appeared much paler than WT embryos (e). Massive amount of blood cells leaked out from blood vessels within the yolk sac (b) and the embryo proper (c) of the Ergkd/kd animal, in comparison to the WT control (f–g), although its major vasculature appeared normal, as indicated by CD31 (PECAM-1) staining (d, compare to h, arrows indicate blood vessels). Scale bars = 1,000μm (a,e), 100μm (b,c,f,g), and 500μm (d,h), respectively. (F) Tie2-Cre leads to restoration of Erg expression in hematopoietic and endothelial cells and rescues the lethal phenotype of Ergkd/kd embryos; animals counted here were from crosses between Tie2-Cre;Ergkd/kd males and Ergkd/+ females (from 8 litters).

The requirement for ERG during development is restricted to hematopoietic and endothelial cells

All Ergkd/kd embryos died around E10.5–E11.5, apparently due to extensive hemorrhage (Fig. 1E). At E10.5, Ergkd/kd embryos and their yolk sacs appeared pale compared to their WT littermates (Fig. 1E, compare a to e). Most blood vessels within embryos and yolk sacs were nearly empty; numerous blood cells leaked from vessels and accumulated outside (Fig. 1E, b–c compare to f–g). Despite extensive hemorrhage, the major vasculature appeared normal as assessed by CD31 staining (Fig. 1E, compare d to h). Primitive hematopoiesis was also largely unperturbed, as primitive erythrocytes were quite abundant in Ergkd/kd embryos at this stage and were morphologically normal (Fig. 1E, b–c compare to f–g).

In the Ergkd allele, Cre-mediated excision of the floxed Neo-ST restores Erg expression (Fig. 1A). Therefore, the reversibility of the mutant allele permits assignment of the cell type(s) in which loss of ERG leads to the embryonic lethal phenotype. We first interbred Ergkd to Sox2-Cre, which expresses Cre in the developing embryo, and not in the placenta 19. We found all Sox2-Cre;Ergkd/kd animals were normal as adults (data not shown), suggesting that the embryonic lethal phenotype in Ergkd/kd mice is not caused by a defect in Ergkd/kd placenta. Since the major defect in Ergkd/kd mice appeared to reside in the hematopoietic and endothelial system, we next asked whether Tie2-Cre 18, which restricts Cre expression to these two cell lineages, could rescue the early lethal phenotype. This was indeed the case and Tie2-Cre;Ergkd/kd mice survived as adults. In intercrosses of Tie2-Cre;Ergkd/kd and Ergkd/+ mice, all surviving Ergkd/kd mice carried Tie2-Cre (Fig. 1F), suggesting that Tie2-Cre-mediated restoration of Erg expression in hematopoietic and endothelial cells is essential for rescue of the lethal phenotype. To confirm that Tie2-Cre-mediated recombination is restricted to endothelial and hematopoietic cells, we bred Tie2-Cre mice to mice carrying a conditional Cre reporter, Rosa26-LSL-YFP (R26Y) 20. Cre-mediated excision of a ST cassette in this reporter leads to constitutive expression of YFP from the Rosa26 locus. In rescued Tie2-Cre;Ergkd/kd;R26Y adults, we found that the majority (>90%) of cells in hematopoietic organs, specifically in BM or spleen, were YFP+; in contrast, in mammary glands or prostates, only lineage positive cells (Lin+, including CD45+ leukocytes, CD31+ endothelial cells, and Ter119+ erythrocytes) were YFP+ (Fig. S1B), thus confirming the specificity of Tie2-Cre-mediated rescue.

These rescue experiments suggest that the major defects during development in Ergkd/kd embryos lie in the endothelial and hematopoietic cells. Since Erg expression remains disrupted in all other non-endothelial/hematopoietic cells in Tie2-Cre;Ergkd/kd mice, ERG may not be critically required in these cell types/tissues. However, this conclusion does not preclude functions of ERG in them that may be compensated by other ETS family TFs upon Erg-loss.

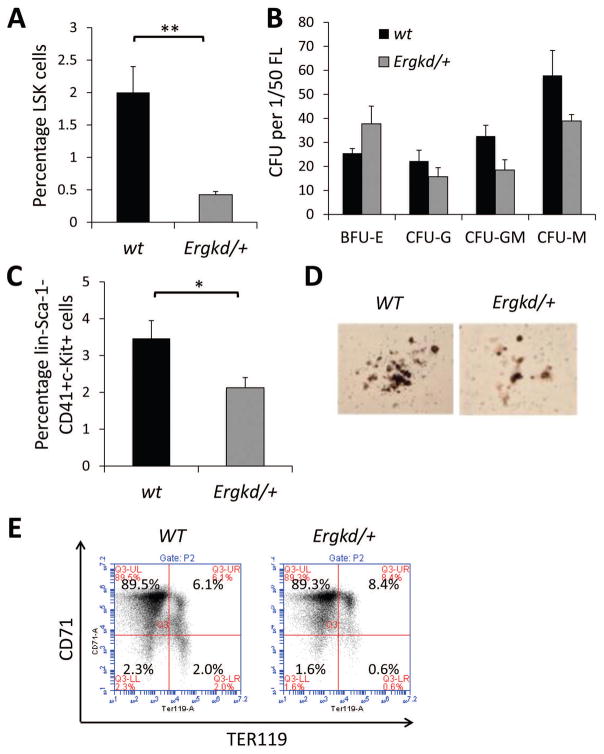

Reduced Erg dosage perturbs fetal liver hematopoiesis

As all Ergkd/kd embryos die before E11.5, we analyzed fetal liver (FL) definitive hematopoiesis in Ergkd/+ embryos (~60% of the WT Erg level) at mid-gestation (E12.5–E13.5). Even in Ergkd/+ FLs, we observed a significant reduction in the percentage of fetal HSPCs within the Lin−Sca-1+c-kit+ (LSK) gate (Fig. 2A), and a slight reduction in the number of myeloid colonies (Fig. 2B). Moreover, we observed a significant reduction in the percentage of fetal megakaryocytic progenitors (MPs) (Lin−Sca-1−c-kit+CD41+) in E12.5 Ergkd/+ FLs compared to WT FLs (Fig. 2C). In megakaryocytic colony-forming assays, we observed that acetylcholine+ megakaryocytic colonies of E12.5 Ergkd/+ FL cells were smaller in size compared to WTs (Fig. 2D). In contrast, erythropoiesis in Ergkd/+ FLs appeared largely normal as assessed by CD71 and TER119 (Fig. 2E) staining and by colony-forming assays (BFU-E, Fig. 2B). Taken together, we conclude that reduced Erg expression during development impairs FL definitive hematopoiesis, including megakaryopoiesis, but does not appear to significantly affect erythropoiesis.

Figure 2. Fetal hematopoiesis is perturbed upon ~40% reduction in the Erg level.

(A) FACS analysis showing a significant reduction in the percentage of HSPCs in the LSK gate in E12.5 Ergkd/+ fetal livers (FLs) compared to that of their WT littermates. (B) Hematopoietic colony analysis of E12.5 FLs showing slight reduction in myeloid colony formation [CFG-G (granulocyte), CFU-GM (granulocyte, macrophage), CFU-M (macrophage)], and no significant change in erythroid colony formation (BFU-E) in Ergkd/+ mice compared to WTs. (C) FACS analysis showing a reduction of Lin-Sca-1−c-kit+CD41+ megakaryocytic progenitors (MPs) in Ergkd/+ E12.5 FLs compared to WTs. (D) Mega-Cult megakaryocytic colony-forming assay showing less acetylcholine+ megakaryocytes (large brown cells) in megakaryocytic colonies formed from Ergkd/+ E12.5 FL cells compared to WTs (magnification, 40x). (E) FACS analysis based on CD71 and TER119 staining in mid-gestation FLs showing largely normal erythropoiesis in Ergkd/+ mice compared to WT controls. Data represent mean ± SEM. P values: *p≤0.05; **p≤0.01.

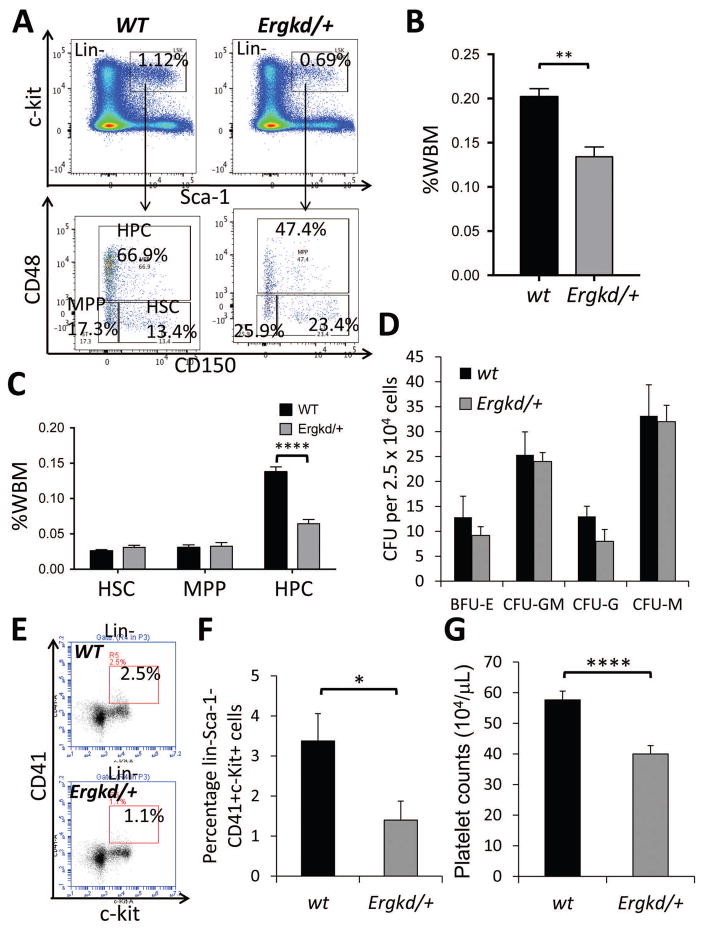

Reduced Erg dosage perturbs adult hematopoiesis

Although adult Ergkd/+ mice appeared normal, they were smaller than WT littermates at younger ages (data not shown). In adult mice derived from Ergkd/+ and WT crosses, the ratio of Ergkd/+:WT progeny was 0.76:1 (expected ratio 1:1), suggesting loss of some Ergkd/+ animals during development. We analyzed BM of adult mice and found that BM from Ergkd/+ mice also contained a significantly smaller HSPC population in the LSK gate than that of WT mice (Fig. 3A–B). We analyzed HSPC subpopulations within the LSK gate based on the SLAM markers 26, and found that the reduced LSK HSPC population was mainly due to a signification reduction in the restricted hematopoietic progenitor (HPC, CD48+) subpopulation in the Ergkd/+ BM (Fig. 3A,C). Although percentages of the hematopoietic stem cell (HSC, CD150+CD48−) and multipotent hematopoietic progenitor (MPP, CD150−CD48−) subsets within the LSK gate were both increased proportionally (Fig. 3A), their percentages based on the whole BM (WBM) were not significantly altered (Fig. 3C). We also analyzed the LSK subpopulations based on the CD34 and Flt3 staining 27; we found that the percentages (based on the LSK gate) of more differentiated short-term HSC (ST-HSC, CD34+Flt3−) and multipotent progenitor (MPP, CD34+Flt3+) subpopulations were both reduced in the Ergkd/+ BM, whereas those of the long-term HSC (LT-HSC, CD34−Flt3−) subpopulation were increased, compared to those in the WT BM (Fig. S2A–B). BM colony assay revealed that Ergkd/+ animals formed slightly less myeloid and erythroid colonies compared to WTs (Fig. 3D). Moreover, the percentage of MPs in Ergkd/+ BM was significantly reduced (Fig. 3E–F). Consistent with this, Ergkd/+ adult mice exhibited significantly reduced platelet counts (Fig. 3G and Table S1), although their red blood cell (RBC) and white blood cell (WBC) counts were similar to those of WT mice (Table S1). These data indicate that ~40% reduction in the Erg dosage perturbs the HSPC and megakaryocytic compartments of BM hematopoiesis.

Figure 3. Adult hematopoiesis is perturbed upon ~40% reduction in the Erg level.

(A) FACS analysis showing changes in the percentage of LSK cells, as well as the HSC, MPP and HPC subsets of LSK cells in the bone marrow (BM) of Ergkd/+ mice compared to WTs. Percentages of LSK cells were shown as percentages of lineage-negative (Lin-) cells. (B) Quantification of BM LSK cells in Ergkd/+ animals compared to WTs. Percentages of LSK cells here were shown as percentages of whole bone marrow (WBM) cells. (C) Quantification of the percentage of HSC, MPP and HPC subsets within the WBM in Ergkd/+ animals compared to WTs. (D) Hematopoietic colony analysis of BM samples. (E) FACS analysis showing a reduction in the percentage of Lin-Sca-1−c-kit+CD41+ MPs in the BM of Ergkd/+ mice compared to WTs. (F) Quantification of BM MPs in Ergkd/+ animals compared WTs for E. (G) CBC analysis demonstrated significantly reduced platelet counts in Ergkd/+ adult mice compared to WT controls. Data represent mean ± SEM. P values: *p≤0.05; **p≤0.01; ****p≤0.001.

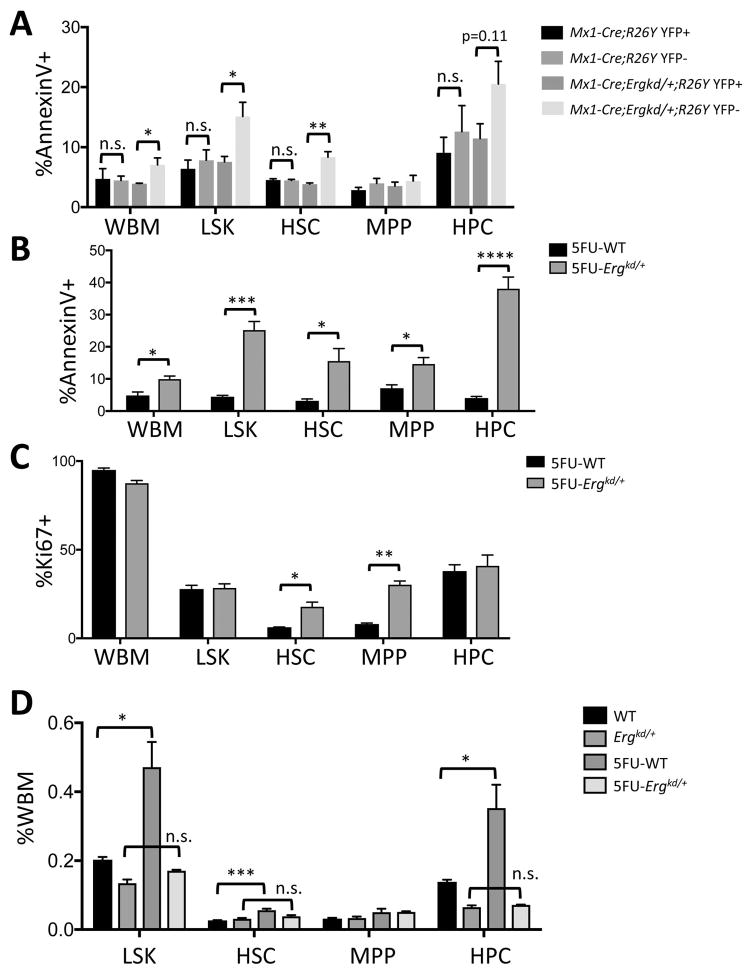

Reduced Erg dosage affects survival and proliferation of HSPCs

We measured apoptosis (by Annexin V staining) and proliferation (by Ki67 staining) of WBM and HSPC (within the LSK gate) populations, as well as HSPC subpopulations based on CD48/CD150 staining (i.e., HSC, MPP, HPC) in Ergkd/+ and WT adult mice. We found that compared to WT mice, the LSK, HSC and HPC compartments in the Ergkd/+ mice contained significantly more apoptotic cells (Fig. 4A); in addition, both the LSK and HPC compartments in the Ergkd/+ mice contained significantly less proliferative cells (Fig. 4B). Further analysis of cell cycle status revealed that within the LSK and HPC compartments of Ergkd/+ adult mice, significantly more cells were at the G0 stage, whereas significantly less cells were at the G1 stage, when compared to those of WT mice (Fig. 4C). Together, these data suggest that at the steady state, reduced Erg dosage largely affects BM hematopoietic progenitors (i.e., HPCs), leading to their reduced survival and proliferation.

Figure 4. Reduced Erg dosage affects survival and proliferation of HSPCs.

(A–B) Summaries of FACS data showing percentages of Annexin V+ apoptotic cells (A) and Ki67+ proliferating cells (B) in each indicated population. (C) Summary of FACS-based cell cycle analysis data for each indicated BM hematopoietic cell subpopulation. Data represent mean ± SEM. P values: *p≤0.05; **p≤0.01; ***p≤0.005; ****p≤0.001.

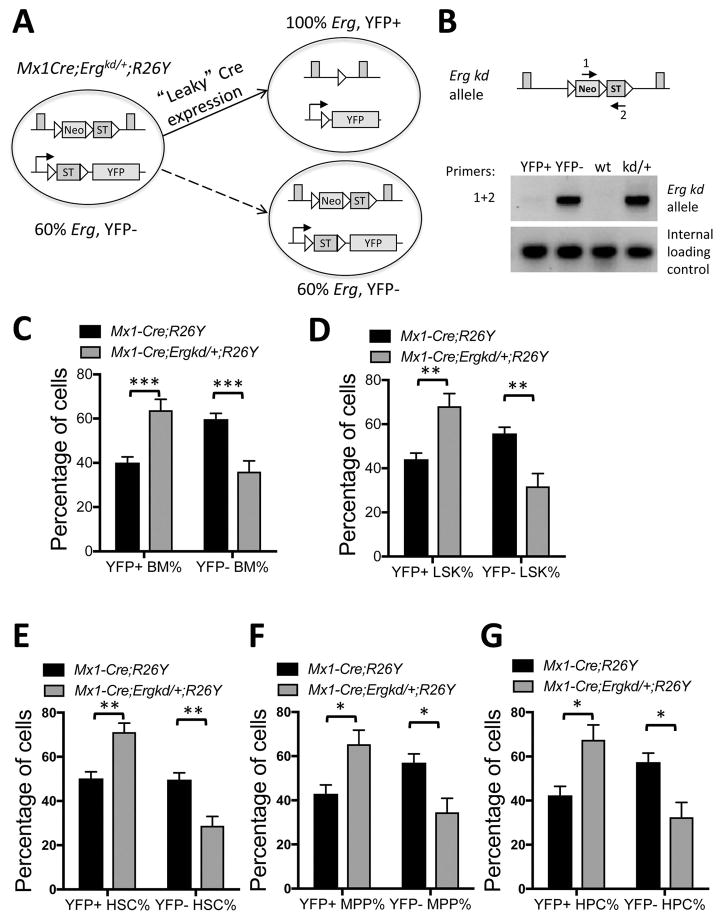

Ergkd/+ HSPCs fail to compete with Erg-restored HSPCs in vivo

To determine whether restoration of Erg expression to the WT level rescues the hematopoietic defect of Ergkd/+ adult mice, we performed a genetic mosaic analysis in Mx1-Cre;Ergkd/+;R26Y mice (compared to Mx1-Cre;R26Y control mice). Even without administration of pI-pC, Mx1-Cre exhibits leaky Cre expression in the hematopoietic system (Fig. 5). We reasoned that leaky Cre expression in Mx1-Cre;Ergkd/+;R26Y mice would lead to restoration of Erg in a subset of hematopoietic cells. These cells should be YFP+ due to Cre-mediated activation of the YFP reporter together with restoration of Erg, whereas YFP− cells in the same animal should remain Ergkd/+; these two cell populations would compete in vivo (Fig. 5A). To confirm restoration of the Erg allele in YFP+ cells, we sorted YFP+ and YFP− BM cells from Mx1-Cre;Ergkd/+;R26Y mice and performed PCR for their genomic DNA to determine whether the Neo-ST cassette in the Ergkd allele was deleted by Mx1-Cre. While we observed a strong PCR signal from the YFP− population, we only detected a trace PCR signal from the YFP+ population (Fig. 5B), suggesting YFP+ BM cells were largely Erg-restored (i.e., with Neo-ST deletion). Next we analyzed the percentages of YFP+ and YFP− populations in BM and peripheral blood of Mx1-Cre;Ergkd/+;R26Y mice and Mx1-Cre;R26Y control mice. In BM of Mx1-Cre;Ergkd/+;R26Y mice, we found that the percentages of the YFP− (Ergkd/+) cells in the WBM cells, LSK HSPCs, and Lin− BM cells were all significantly reduced compared to those in BM of Mx1-Cre;R26Y control mice (Figs. 5C–D and Fig. S3A); the percentages of YFP− cells in all HSPC subpopulations were also reduced in Mx1-Cre;Ergkd/+;R26Y mice compared to those in Mx1-Cre;R26Y mice (Fig. 5E–G). Furthermore, we also found the percentages of YFP− PB cells were reduced, but with less statistical significance (Fig. S3B). The percentages of YFP− BM cells, in particular, YFP− LSK cells were further reduced so that in aged (>1.5 year) Mx1-Cre;Ergkd/+;R26Y mice, the majority of BM cells and LSK cells were YFP+ (Fig. S3C). Together, these data suggest that YFP− BM hematopoietic cells with ~40% reduction in the Erg dosage were outcompeted by YFP+ cells with a WT level of Erg, in particularly in the LSK compartment.

Figure 5. Ergkd/+ HSPCs were outcompeted by Erg-restored HSPCs in the same animal.

(A) Schematic diagram showing Cre-mediated restoration of Erg and simultaneous activation of the conditional YFP reporter in the same cell leading to formation of YFP+ Erg-restored cells from YFP− Ergkd/+ cells. (B) PCR analysis (primers 1+2) of genomic DNAs of YFP+ and YFP− BM cells sorted from the same Mx1-Cre;Ergkd/+;R26Y mouse showing deletion of the Neo-ST cassette in the YFP+ BM cells (thus Erg restored to WT). Genomic DNAs from WT and Ergkd/+ mice were used as controls for the PCR reaction. (C–G) Quantification of percentages of YFP+ (Erg-restored) and YFP− (Erg-kd) WBM cells (C), LSK cells (D), HSCs (E), MPPs (F) and HPCs (G) from Mx1-Cre;R26Y control mice and Mx1-Cre;Ergkd/+;R26Y experimental mice. Data represent mean ± SEM. P values: *p≤0.05; **p≤0.01; ***p≤0.005.

Reduced Erg dosage impairs survival of proliferating HSPCs

We measured percentages of Annexin V+ apoptotic cells in BM from Mx1-Cre;Ergkd/+;R26Y and Mx1-Cre;R26Y adult mice (Fig. S4). Within the same Mx1-Cre;Ergkd/+;R26Y mice, we observed more apoptotic cells in the YFP− (thus, Ergkd/+) LSK, HSC, and HPC (to a lessor degree for HPC) compartments, compared to the YFP+ (thus, Erg-restored) LSK, HSC and HPC compartments (Fig. 6A). In contrast, we did not observe such differences when comparing the YFP− and YFP+ subsets within the Mx1-Cre;R26Y control mice, suggesting increased apoptosis of HSPCs within these subsets with reduced Erg dosage (Fig. 6A).

Figure 6. Reduced Erg dosage impaired survival of proliferating HSPCs.

(A) Quantification of percentages of Annexin V+ apoptotic cells in YFP+ and YFP− WBM, LSK, HSC, MPP and HPC subsets from Mx1-Cre;R26Y control mice and Mx1-Cre;Ergkd/+;R26Y experimental mice. (B–C) Quantification of percentages of Annexin V+ apoptotic cells (B) and Ki67+ proliferating cells (C) in WBM, LSK, HSC, MPP and HPC subsets from Ergkd/+ and WT mice 15 days after 5-FU treatment. (D) Quantification of percentages of LSK, HSC, MPP and HPC subsets in WBM from Ergkd/+ and WT mice 15 days after 5-FU treatment. Data represent mean ± SEM. P values: *p≤0.05; **p≤0.01; ***p≤0.005; ****p≤0.001.

To obtain further support for the effect of reduced Erg dosage on the survival of HSPCs, we treated Ergkd/+ and WT mice with 5-FU to induce stress hematopoiesis. Fifteen days after 5-FU injection (i.e., recovery stage), we analyzed their BM compartments and observed significantly more apoptotic cells in the WBM and LSK HSPC populations, as well as in all the LSK subpopulations, from Ergkd/+ mice compared to those from WT controls (Fig. 6B). In addition, we also found that the HSC and MPP subpopulations from the recovering Ergkd/+ mice contained more proliferating cells compared to those of WT mice (Fig. 6C). The increased proliferation of Ergkd/+ HSCs and MPPs during the recovery phase may reflect a compensatory mechanism for increased loss of Ergkd/+ hematopoietic cells from apoptosis. Due to 5-FU-induced stress hematopoiesis, HSCs are driven into cell cycle to repopulate the hematopoietic system, leading to recovery of the LSK HSPCs and expansion of almost all LSK subpopulations (in particular, HSC and HPC subsets, Fig. 6D compare WT to 5FU-WT). In contrast, we observed that Ergkd/+ mice exhibited a severe defect in the recovery of their LSK HSPCs and LSK subpopulations after 5-FU treatment (Fig. 6D, compare Ergkd/+ to 5FU-Ergkd/+), apparently due to their dramatically increased apoptosis. Together, data from both systems support a role of ERG in supporting survival of proliferating HSPCs.

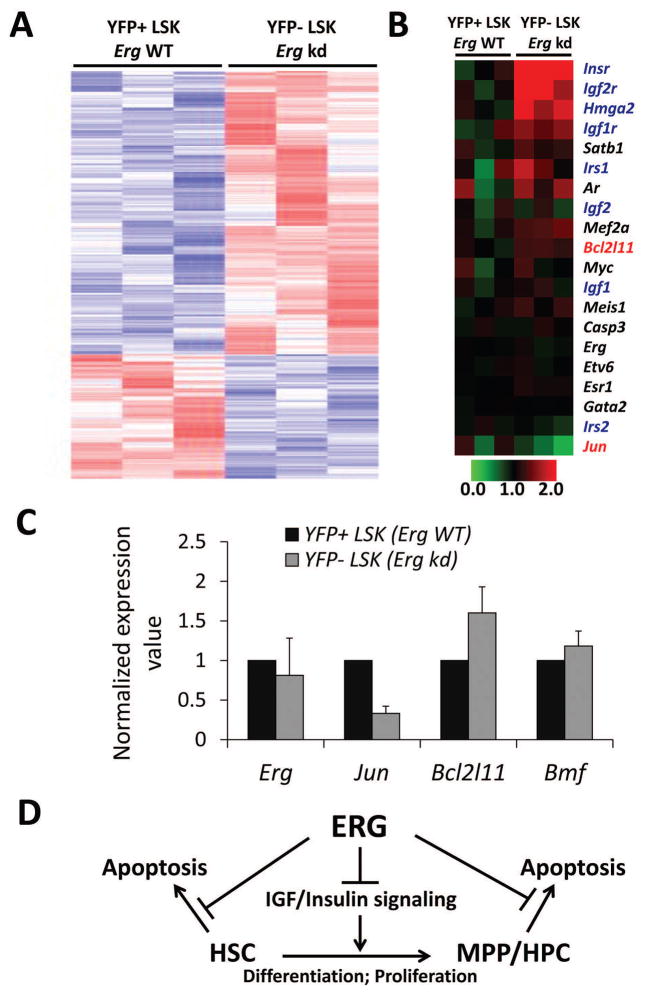

ERG controls expression of a subset of target genes involved in regulating HSPC survival

To identify defects in Ergkd/+ HSPCs at the molecular level, we sorted YFP+ (Erg-restored) and YFP− (Ergkd/+) LSK cells from Mx1-Cre;Ergkd/+;R26Y mice and performed microarray expression profiling. Potential target genes of ERG were studied recently by ChIP-seq analysis in HPC7 cells 28. We integrated our expression data with this ChIP-seq dataset and identified several hundreds of ERG ChIP-seq targets that exhibited differential expression in YFP+ and YFP− LSK cells from Mx1-Cre;Ergkd/+;R26Y mice. Among these genes, about two-thirds exhibited downregulation upon restoration of Erg expression (in YFP+ LSK cells), and about one-third exhibited upregulation (Fig. 7A). Among top downregulated genes, we observed Bcl2l11 (also known as Bim), which encodes for a BH3-only pro-apoptotic member of the Bcl-2 family (Fig. 7B). Of note, loss of Bcl2l11 (or Bmf, encoding another BH3-only pro-apoptotic protein) was shown previously to lead to increased survival and engraftment of HSCs 29. We also found that several genes related to IGF/insulin signaling were downregulated upon restoration of Erg expression (Fig. 7B). Consistent with this, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) 30 revealed significant enrichment of gene sets related to IGF/insulin signaling in Erg-restored LSKs (Fig. S5A). Among top upregulated genes (upon restoration of Erg expression), we observed Jun (Figs. 7B and S5B), which was shown to be important for hematopoietic progenitor survival 31. By qRT-PCR analysis of YFP+ and YFP− LSK cells sorted from Mx1-Cre;Ergkd/+;R26Y mice, we confirmed higher expression of Bcl2l11 in YFP− Ergkd/+ LSK cells than in YFP+ Erg-restored LSK cells; we also observed a slight upregulation of Bmf and profound downregulation of Jun in YFP− Ergkd/+ LSK cells (Fig. 7C). To determine whether expression levels of these three genes exhibited a similar trend in the other two Erg loss-of-function mouse models, we queried their corresponding microarray expression profiling data and confirmed upregulation of Bcl2l11 and Bmf and downregulation of Jun in ErgMld2/+ LSK cells 15 and/or Erg+/− LT-HSCs 16, compared to their corresponding WT controls (Fig. S5C–D). Collectively, these data suggest that in HSPCs, ERG positively regulates expression of its target gene Jun and represses expression of pro-apoptotic genes such as Bcl2l11 and possibly also Bmf.

Figure 7. Microarray analysis and validation of select target genes of ERG.

(A) Heatmap (red to white to blue indicate highest to intermediate to lowest expression level) showing differential expression of potential target genes of ERG (based on ChIP-seq from 28) in YFP+ and YFP− LSK cells sorted from the same Mx1-Cre;Ergkd/+;R26Y mouse. (B) Heatmap showing differential expression of select ERG target genes as in A. Genes related to apoptosis are marked in red; genes involved in IGF/insulin signaling are marked in dark blue. Expression values were normalized to the mean of those of Erg-WT samples (=1). (C) qRT-PCR validation showing reduced expression of Jun and increased expression of Bcl2l11 and Bmf in YFP− LSK cells, compared to YFP+ LSK cells (=1) from the same Mx1-Cre;Ergkd/+;R26Y mouse. (D) Schematic diagram showing multiple roles of ERG in regulating HSPCs.

Discussion

Through characterization of a rescuable Erg knockdown allele, we demonstrated critical roles of ERG in endothelial and hematopoietic cells during development. These include requirements in definitive hematopoiesis and megakaryopoiesis, and in controlling the number and survival of HSPCs. Previously it was reported that knockdown of Erg in mouse ES cells or in zebrafish embryos failed to exhibit a hematopoietic defect 32, 33. We suspect that primitive rather than definitive hematopoiesis was studied in these experiments. Given that ERG is largely dispensable at this early stage of hematopoiesis, the observed results can be explained. In adults, a role of ERG in maintaining survival of proliferating HSPCs has been established here by genetic mosaic analysis and analysis of 5-FU-induced stress hematopoiesis. This function of ERG may be in part mediated by target genes such as Bcl2l11 and Jun, which are negatively and positively regulated by ERG, respectively. Loss-of-function studies of Bcl2l11 (Bim) and Bmf have demonstrated important roles of these BH3-only pro-apoptotic proteins in limiting survival of HSPCs 29, 34. Interestingly, by mining a recently published microarray dataset for ERG-induced leukemia 35, we found that expression of both Bcl2l11 and Bmf was reduced compared to that of WT controls in leukemic cells from ERG-transgenic mice 35 (Fig. S5E), suggesting ectopic expression of ERG may contribute to leukemogenesis by enhancing survival of leukemic cells. JUN is one of the 121 genes in a recently defined human HSC-related signature derived from CD34+CD38− cord blood cells and is downregulated upon differentiation to progenitors and lineage-positive cells 36. The precise role of its product, c-Jun, in HSCs has not been defined 37. Interestingly, loss of Jun expression in fetuses led to increased apoptosis of fetal liver hematopoietic cells, suggesting c-Jun may play a key role in maintaining survival of hematopoietic progenitors 31, a function similar to that of ERG revealed from this study.

In this study, we also observed upregulation of many genes in the IGF/insulin pathways in HSPCs with reduced Erg dosage (Fig. 6B). Although IGF/IGF1R signaling is not essential for adult hematopoiesis [38, 39, and Y.X and Z.L., unpublished observation], uncontrolled activation of this pathway can lead to increased activation, proliferation and eventual exhaustion of HSCs 38. Recent studies that employed a conditional knockout model of Erg revealed that total loss of ERG dramatically accelerated differentiation of HSCs. Therefore, a key role of ERG in hematopoiesis may relate to maintenance of HSCs by restricting their differentiation 16. Erg-loss in HSPCs may lead to elevated activation of IGF/IGF1R signaling, which may cause exhaustion of HSCs and in part account for accelerated differentiation of HSCs associated with Erg knockout. Overall, our data, together with those from other groups, demonstrate that ERG plays multiple essential roles in HSPCs, and maintains a proper balance between differentiation, proliferation and survival (Fig. 7D). Although ERG may be dispensable for leukemic transformation 16, its expression may yet contribute to leukemogenesis in part by promoting survival of leukemic cells.

Conclusion

The role of ERG, an ETS family transcription factor, in regulating hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells remains inadequately defined. By utilizing an engineered allele of the Erg gene that leads to reduced ERG protein expression, we unveil a previously unappreciated role of ERG in maintaining survival of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, in particular during stress hematopoiesis. This ERG function is mediated in part by activating Jun and by repressing Bcl2l11, two of its target genes, and can be potentially utilized by leukemic cells to increase their survival.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grants support: This work was supported by NIH grant R01 HL107663 (to Z.L.), AACR-Aflac, Incorporated Career Development Award for Pediatric Cancer Research (10-20-10-LI, to Z.L.), and BWH Startup Fund (to Z.L.). This work was also supported in part by a Center of Excellence in Molecular Hematology award from NIDDK (to S.H.O.) and by grant from DOD (PC060492, to S.H.O.). S.H.O. is an Investigator of HHMI. M.L.K was a MD-Fellow of the Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds. J.-H.K is supported by the Emmy Noether-Programme from the DFG (KL-2374/2-1) and the German Cancer Aid (DKH-109251).

We thank Drs. Luwei Tao and Douglas Linn for analyzing YFP expression in mammary glands and prostates, Dr. Maaike van Bragt for help with microarray sample preparation, and Drs. Grigoriy Losyev and Yiling Qiu for flow cytometry. This work was supported by NIH grant R01 HL107663 (to Z.L.), AACR-Aflac, Incorporated Career Development Award for Pediatric Cancer Research (10-20-10-LI, to Z.L.), and BWH Startup Fund (to Z.L.). This work was also supported in part by a Center of Excellence in Molecular Hematology award from NIDDK (to S.H.O.) and by grant from DOD (PC060492, to S.H.O.). S.H.O. is an Investigator of HHMI. M.L.K was a MD-Fellow of the Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds. J.-H.K is supported by the Emmy Noether-Programme from the DFG (KL-2374/2-1) and the German Cancer Aid (DKH-109251).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Authorship Contributions

Ying Xie: Collection and/or assembly of data, Data analysis and interpretation, Manuscript writing

Mia Lee Koch: Collection and/or assembly of data, Data analysis and interpretation, Financial support, Manuscript writing

Xin Zhang: Collection and/or assembly of data

Melanie J. Hamblen: Collection and/or assembly of data

Frank J. Godinho: Collection and/or assembly of data

Yuko Fujiwara: Collection and/or assembly of data

Huafeng Xie: Other (technical support for flow cytometric analysis of HSPC subsets)

Jan-Henning Klusmann: Conception and design, Financial support

Stuart H. Orkin: Conception and design, Financial support

Zhe Li: Conception and design, Financial support, Collection and/or assembly of data, Data analysis and interpretation, Manuscript writing, Final approval of manuscript

References

- 1.Martens JH. Acute myeloid leukemia: a central role for the ETS factor ERG. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2011;43:1413–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tomlins SA, Rhodes DR, Perner S, et al. Recurrent fusion of TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor genes in prostate cancer. Science. 2005;310:644–648. doi: 10.1126/science.1117679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zucman J, Melot T, Desmaze C, et al. Combinatorial generation of variable fusion proteins in the Ewing family of tumours. Embo J. 1993;12:4481–4487. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06137.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ginsberg JP, de Alava E, Ladanyi M, et al. EWS-FLI1 and EWS-ERG gene fusions are associated with similar clinical phenotypes in Ewing’s sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1809–1814. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.6.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shimizu K, Ichikawa H, Tojo A, et al. An ets-related gene, ERG, is rearranged in human myeloid leukemia with t(16;21) chromosomal translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:10280–10284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dastugue N, Lafage-Pochitaloff M, Pages MP, et al. Cytogenetic profile of childhood and adult megakaryoblastic leukemia (M7): a study of the Groupe Francais de Cytogenetique Hematologique (GFCH) Blood. 2002;100:618–626. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byrd JC, Mrozek K, Dodge RK, et al. Pretreatment cytogenetic abnormalities are predictive of induction success, cumulative incidence of relapse, and overall survival in adult patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia: results from Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 8461) Blood. 2002;100:4325–4336. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baldus CD, Liyanarachchi S, Mrozek K, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia with complex karyotypes and abnormal chromosome 21: Amplification discloses overexpression of APP, ETS2, and ERG genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3915–3920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400272101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baldus CD, Burmeister T, Martus P, et al. High expression of the ETS transcription factor ERG predicts adverse outcome in acute T-lymphoblastic leukemia in adults. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4714–4720. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Metzeler KH, Dufour A, Benthaus T, et al. ERG Expression Is an Independent Prognostic Factor and Allows Refined Risk Stratification in Cytogenetically Normal Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Comprehensive Analysis of ERG, MN1, and BAALC Transcript Levels Using Oligonucleotide Microarrays. J Clin Oncol. 2009 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salek-Ardakani S, Smooha G, de Boer J, et al. ERG is a megakaryocytic oncogene. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4665–4673. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsuzuki S, Taguchi O, Seto M. Promotion and maintenance of leukemia by ERG. Blood. 2011;117:3858–3868. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-320515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carmichael CL, Metcalf D, Henley KJ, et al. Hematopoietic overexpression of the transcription factor Erg induces lymphoid and erythro-megakaryocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:15437–15442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213454109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thoms JA, Birger Y, Foster S, et al. ERG promotes T-acute lymphoblastic leukemia and is transcriptionally regulated in leukemic cells by a stem cell enhancer. Blood. 2011;117:7079–7089. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-317990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loughran SJ, Kruse EA, Hacking DF, et al. The transcription factor Erg is essential for definitive hematopoiesis and the function of adult hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:810–819. doi: 10.1038/ni.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knudsen KJ, Rehn M, Hasemann MS, et al. ERG promotes the maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells by restricting their differentiation. Genes Dev. 2015;29:1915–1929. doi: 10.1101/gad.268409.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuhn R, Schwenk F, Aguet M, et al. Inducible gene targeting in mice. Science. 1995;269:1427–1429. doi: 10.1126/science.7660125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kisanuki YY, Hammer RE, Miyazaki J, et al. Tie2-Cre transgenic mice: a new model for endothelial cell-lineage analysis in vivo. Dev Biol. 2001;230:230–242. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayashi S, Lewis P, Pevny L, et al. Efficient gene modulation in mouse epiblast using a Sox2Cre transgenic mouse strain. Mech Dev. 2002;119(Suppl 1):S97–S101. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(03)00099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Srinivas S, Watanabe T, Lin CS, et al. Cre reporter strains produced by targeted insertion of EYFP and ECFP into the ROSA26 locus. BMC Dev Biol. 2001;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Z, Tognon CE, Godinho FJ, et al. ETV6-NTRK3 fusion oncogene initiates breast cancer from committed mammary progenitors via activation of AP1 complex. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:542–558. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Visvader JE, Fujiwara Y, Orkin SH. Unsuspected role for the T-cell leukemia protein SCL/tal-1 in vascular development. Genes Dev. 1998;12:473–479. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.4.473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Z, Godinho FJ, Klusmann JH, et al. Developmental stage-selective effect of somatically mutated leukemogenic transcription factor GATA1. Nat Genet. 2005;37:613–619. doi: 10.1038/ng1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klusmann JH, Godinho FJ, Heitmann K, et al. Developmental stage-specific interplay of GATA1 and IGF signaling in fetal megakaryopoiesis and leukemogenesis. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1659–1672. doi: 10.1101/gad.1903410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baena E, Shao Z, Linn DE, et al. ETV1 directs androgen metabolism and confers aggressive prostate cancer in targeted mice and patients. Genes Dev. 2013;27:683–698. doi: 10.1101/gad.211011.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oguro H, Ding L, Morrison SJ. SLAM family markers resolve functionally distinct subpopulations of hematopoietic stem cells and multipotent progenitors. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:102–116. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang L, Bryder D, Adolfsson J, et al. Identification of Lin(−)Sca1(+)kit(+)CD34(+)Flt3- short-term hematopoietic stem cells capable of rapidly reconstituting and rescuing myeloablated transplant recipients. Blood. 2005;105:2717–2723. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson NK, Foster SD, Wang X, et al. Combinatorial Transcriptional Control In Blood Stem/Progenitor Cells: Genome-wide Analysis of Ten Major Transcriptional Regulators. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:532–544. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Labi V, Bertele D, Woess C, et al. Haematopoietic stem cell survival and transplantation efficacy is limited by the BH3-only proteins Bim and Bmf. EMBO Mol Med. 2013;5:122–136. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201201235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eferl R, Sibilia M, Hilberg F, et al. Functions of c-Jun in liver and heart development. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:1049–1061. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.5.1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nikolova-Krstevski V, Yuan L, Le Bras A, et al. ERG is required for the differentiation of embryonic stem cells along the endothelial lineage. BMC Dev Biol. 2009;9:72. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-9-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu F, Patient R. Genome-wide analysis of the zebrafish ETS family identifies three genes required for hemangioblast differentiation or angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2008;103:1147–1154. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.179713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herold MJ, Stuchbery R, Merino D, et al. Impact of conditional deletion of the pro-apoptotic BCL-2 family member BIM in mice. Cell death & disease. 2014;5:e1446. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldberg L, Tijssen MR, Birger Y, et al. Genome-scale expression and transcription factor binding profiles reveal therapeutic targets in transgenic ERG myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2013;122:2694–2703. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-477133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eppert K, Takenaka K, Lechman ER, et al. Stem cell gene expression programs influence clinical outcome in human leukemia. Nat Med. 2011;17:1086–1093. doi: 10.1038/nm.2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Behrens A, Sibilia M, David JP, et al. Impaired postnatal hepatocyte proliferation and liver regeneration in mice lacking c-jun in the liver. Embo J. 2002;21:1782–1790. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.7.1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Venkatraman A, He XC, Thorvaldsen JL, et al. Maternal imprinting at the H19-Igf2 locus maintains adult haematopoietic stem cell quiescence. Nature. 2013;500:345–349. doi: 10.1038/nature12303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xie J, Chen X, Zheng J, et al. IGF-IR determines the fates of BCR/ABL leukemia. Journal of hematology & oncology. 2015;8:3. doi: 10.1186/s13045-015-0106-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.