Abstract

The palmaris longus muscle is the most superficial muscle of the volar forearm which demonstrates significant anatomical variance. A reversed palmaris longus muscle is one such variant. Here we discuss two cases in which reversed palmaris longus was postulated as a cause of wrist discomfort.

Keywords: Reversed palmaris longus, nerve compression, wrist pain

Introduction

The palmaris longus (PL) muscle is the most superficial muscle of the volar compartment of the forearm. It has been suggested that its original role may have been in flexion of the metacarpo-phalangeal joints, but that phylogenetic regression now restricts its function to that of an ancillary wrist flexor [1,2]. The muscle shows significant anatomical variance, with described variations including agenesis, hypertrophy, duplication, bifid and accessory slips, in addition to variations in its origin and insertions [3].

A reversed palmaris longus (RPL) muscle, where the belly lies in the distal forearm and the tendon in the proximal forearm, was first described in anatomical literature in 1916 [4] and other cases have since been identified since, although this particular anomaly accounts for only a relatively small proportion of the anatomical variations observed [5–9].

It is recognised in the medical literature that variations of PL muscle anatomy can result in symptomatic conditions involving pain or peripheral nerve compression [10,11]. Although RPL is usually detected as an incidental finding on MRI imaging [8], it has been occasionally identified as a cause of activity-related median or ulnar nerve compression [10,11]. It has not previously been reported as a cause of muscular pain, however, it has been hypothesised that hypertrophy of the muscle belly of the reversed PL (as a result of repetitive movements) can potentiate effort-related compartment syndrome due to the unforgiving nature of the ante-brachial fascia [12]. Here we discuss two cases in which RPL was postulated as a potential cause of muscular discomfort.

Patient 1

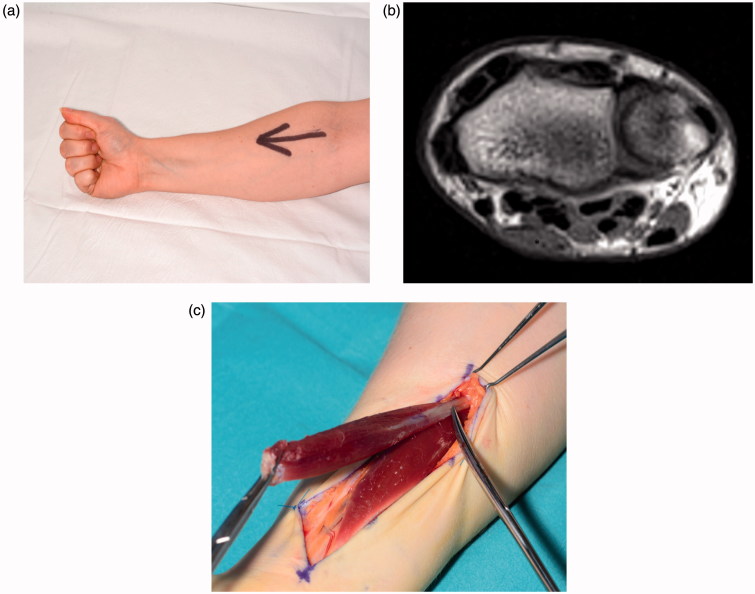

A 30-year old right-handed female competitive weight-lifter presented with a six month history of pain and swelling in the right volar forearm. In the early stages, the symptoms were precipitated by an intense of weight-lifting, and the discomfort lasted for several hours afterwards. However, symptoms became increasingly frequent and were now troublesome during lighter activities such as horse-riding and writing. There were no symptoms of paraesthesia. The patient had no significant past medical history, but was undergoing investigation for right shoulder pain. Clinical examination revealed a visible swelling in the right volar forearm (Figure 1(a)), which co-located with the site of the discomfort. The swelling was absent on the left side. Resisted wrist flexion provoked pain. Examination of the median nerve was unremarkable. An MRI scan of the forearm was initially reported as unremarkable, but request was made for review of the images, and a RPL was identified (Figure 1(b)). Initial management included a period of rest and splintage, and treatment with ice and topical and oral anti-inflammatories. However, symptoms worsened, and a decision was made to excise the palmaris muscle belly. The operation was carried out uneventfully under general anaesthetic, and a sizeable palmaris longus muscle belly was identified and excised through a longitudinal incision (Figure 1(c)). Post-operative progress was good, with no wound-healing problems, and on review at three months the patient reported complete resolution of her discomfort on writing and horse-riding. She had not returned to competitive weight-lifting because of ongoing right shoulder pain due to a SLAP tear for which she was awaiting operative intervention.

Figure 1.

(a) Visible swelling in the right distal volar forearm on clinical examination; (b) An axial section of an MRI scan clearly demonstrating a superficial muscle belly at the level of the distal radio-ulnar joint in keeping with a reversed palmaris longus (*); (c) A sizeable reversed palmaris longus muscle belly in right distal volar forearm.

Patient 2

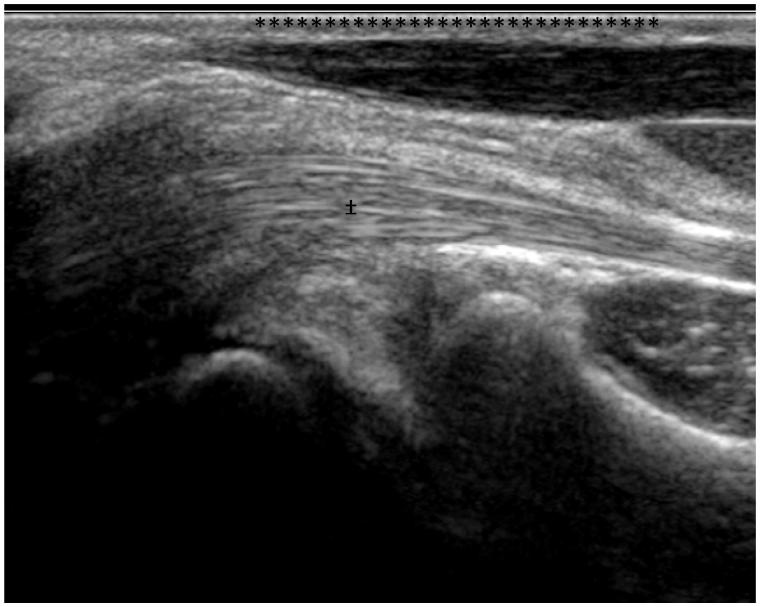

A 17-year-old right handed student, a keen sportsman, presented with acute pain and swelling at the right volar wrist which had developed following a routine upper body work-out at the gym. The pain had settled temporarily following a period of wrist splintage and a course of oral anti-inflammatory medication, but it now recurred acutely during each gym session. There was no discomfort between times, and no symptoms of paraesthesia. Clinical examination revealed a prominence of the muscles in the volar forearm, but this appeared symmetrical with the left side. Examination of the median nerve was unremarkable. An USS-scan was requested, which demonstrated a reversed palmaris muscle at the site of the discomfort (Figure 2) and identified no other potential causes of the pain.

Figure 2.

A longitudinal section of an ultra-sound clearly demonstrating a reversed palmaris longus muscle belly (*) lying onto of the flexor retinaculum. The deep flexor tendons (‡) and radial carpal joint lie inferiorly.

Again, operative treatment was discussed. Under general anaesthetic, a large distal palmaris muscle belly was identified and excised through a longitudinal incision. Healing was uneventful, other than a transient paraesthesia in the median nerve distribution. The patient re- commenced strengthening exercises at the gym six weeks post-operatively and reported complete resolution of his previous discomfort.

Discussion

The PL muscle shows significant anatomical variation, with unilateral agenesis accounting for the most common variant, in approximately 2% to 25% of the population [13–15]. A diverse collection of other anatomical variants (including accessory PL, tripleheaded PL, duplicate or bifid PL, reversed PL, multiple anomalous insertions at the wrist) are found in approximately 9% of the population [15]. It is important for the hand surgeon to be aware of the anatomical variants of the PL to prevent intra-operative confusion and to allow appropriate intervention in the event of clinical symptomatology.

The RPL muscle belly lies within the distal volar forearm, where it is usually an incidental finding on imaging or during operative exploration [8,9]. However, on occasion, especially if oedematous or inflamed, the RPL can cause symptomatic compression of the median nerve, usually with effort-related symptoms [16]. In such cases, surgical excision has been shown to provide immediate long-term relief of symptoms. More rarely, variations of RPL extending into Guyon’s canal can result in the compression of the ulnar nerve [9,11], again with relief of symptoms on surgical excision [11].

The two cases presented here occurred in high-level sportspeople. Unlike the findings of other reported cased of RPL [5,6,8,11,14–16], our patients did not complain of paraesthesia. Instead they had non-specific symptoms of pain and swelling of the volar aspect of the distal forearm. We believe that hypertrophy of the RPL muscle belly within the unyielding ante-brachial fascia resulted in an effort-related compartment syndrome, as with other muscles within the forearm [12]. Similar to the aforementioned reported cases, surgical intervention resulted in total resolution of symptoms in both of our patients. This highlights the benefits of early identification and surgical intervention.

Interestingly, we also operated on a third patient with radiological evidence of a RPL, however intra-operatively they were found not to possess this. We have not identified in the literature any other cases of false positive reports of RPL. In this patient the site of discomfort was localised at the level of the wrist rather than in the distal forearm of the other two patients. We hypothesised that in this patient, the distal belly of the RPL muscle may have inserted into the flexor retinaculum or from the flexor carpi radialis tendon, as has previously been described [14]. However, as surgical exploration was negative for any abnormality, we concluded retrospectively that the ultrasound findings might represent resolving haematoma from an unrecognised trauma. We note that other groups have reported the occurrence of false negatives on MRI imaging due to RPL muscle belly being of similar tissue density to the other muscle bellies in the forearm [8], and we experienced a similar issue in Patient 1.

Conclusion

The palmaris longus muscle is a useful surgical landmark in the forearm, and a potential source of tendon graft to the reconstructive surgeon. It is important for the surgeon to be aware both of the normal PL anatomy and of the anatomical variations that can arise. It should be remembered that these anatomical variations may be symptomatic, and that a high index of clinical suspicion should be used in combination with imaging techniques.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Mark Twoon, MB ChB, is an academic Foundation year one trainee at St John?s Hospital, Livingston, Scotland.

Christopher David Jones, MBBS, is a ST3 Plastic surgical trainee at St John?s Hospital, Livingston, Scotland.

Jon Foley, MB ChB, is a Consultant radiologist at St John?s Hospital, Livingston, Scotland.

Dominique Davidson, FRCS (Plas), is a Consultant Plastic and Hand Surgeon at St John's Hospital, Livingston, Scotland.

References

- 1.McMinn RMH, editor. Last’s anatomy: regional and applied. 9th ed London (UK): Churchill Livingstone; 1994. p. 89. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeybek A, Gurunluoglu R, Cavdar S, et al. . A clinical reminder: a palmaris longus muscle variation. Ann Plast Surg. 1998;41:224–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackhouse KM, Churchill DD.. Anomalous palmaris longus muscle producing carpal tunnel-like compression. Hand 1975;7:22–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrison JT. A palmaris longus muscle with a reversed belly forming an accessory flexor muscle of the little finger. J Anat Physiol 1916;50:324–326. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Depuydt KH, Schuurman AH, Kon M.. Reversed palmaris longus muscle causing effort-related median nerve compression. J Hand Surg Br. 1998;23:117–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bencteux P, Simonet J, el Ayoubi L, et al. . Symptomatic palmaris longus muscle variation with MRI and surgical correlation: report of a single case. Surg Radiol Anat. 2001;23:273–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yildiz M, Sener M, Aynaci O.. Three-headed reversed palmaris longus muscle: a case report and review of the literature. Surg Radiol Anat. 2000;22:217–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schuurman AH, van Gils AP.. Reversed palmaris longus muscle on MRI: report of four cases. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:1242–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogun TC, Karalezli N, Ogun CO.. The concomitant presence of two anomalous muscles in the forearm. Hand (N Y). 2007;2:120–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Still J, Kleinert H.. Anomalous muscles and nerve entrapment in the wrist and hand. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1973;52: 394–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Regan PJ, Roberts JO, Bailey BN.. Ulnar nerve compression caused by a reversed palmaris longus muscle. J Hand Surg Br. 1988;13:406–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martens MA, Moeyersoons JP.. Acute and recurrent effort-related compartment syndrome in sports. Sports Med. 1990;9:62–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reimann AF, Daseler EH, Anson BJ, et al. . The palmaris longus muscle and tendon: a study of 1600 extremeties. Anat Rec. 1944;89:495–505. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Acikel C, Ulkur E, Karagoz H, Celikoz B.. Effort-related compression of median and ulnar nerves as a result of reversed three-headed and hypertrophied palmaris longus muscle with extension of Guyon’s canal. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2007;41:45–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park MJ, Namdari S, Yao J.. Anatomic variations of the palmaris longus muscle. Am J Orthop. 2010;39:89–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murabit A, Gnarra M, Mohamed A. Reversed palmaris longus muscle: anatomical variant – case report and literature review. Can J Plast Surg. 2013;21:55–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]