Abstract

Objectives:

The objective of this study is to present the outcomes of men undergoing implantation of artificial urinary sphincter, after treatment for prostate cancer and also to determine the effect of radiotherapy on continence outcomes after artificial urinary sphincter (AUS) implantation.

Materials and Methods:

A prospectively acquired database of all 184 patients having AUS insertion between 2002 and 2012 was reviewed, and demographic data, mode of prostate cancer treatment(s) before implantation, and outcome in terms of complete continence (pad free, leak free) were assessed. Statistical analysis was performed by Chi-squared and Fisher's exact tests.

Results:

A total of 58 (32%) men had bulbar AUS for urodynamically proven stress urinary incontinence consequent to treatment for prostate cancer in this period. Median follow-up post-AUS activation was 19 months (1–119). Forty-eight (83%) men had primary AUS insertion. Twenty-one (36%) men had radiotherapy as part of or as their sole treatment. Success rates were significantly higher in nonirradiated men having primary sphincter (89%) than in irradiated men (56%). Success rates were worse for men having revision AUS (40%), especially in irradiated men (33%).

Conclusion:

Radiotherapy as a treatment for prostate cancer was associated with significantly lower complete continence rates following AUS implantation.

Keywords: Artificial urinary sphincter, postprostatectomy incontinence, prostate cancer, radiotherapy

INTRODUCTION

Urinary incontinence following all modalities of prostate cancer treatment confers a significant socioeconomic burden worldwide.[1,2] This problem will only increase with the increasingly aged population. Advances in prostate cancer diagnostics mean that more men, in particular more elderly men are receiving this diagnosis. We are now treating an aging population that is more active and healthier than the traditional cohort of elderly patients. Most are functionally independent and have a longer life expectancy, and they expect and demand curative treatments for both their prostate cancer and the consequences of its treatment.[3,4,5,6]

The artificial urinary sphincter (AUS) remains the gold standard for the surgical treatment of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) in men.[7] Male SUI occurs in between 3% and 87% following treatment for prostate cancer, depending on the definition of incontinence used.[8,9,10,11] SUI is reported in 1.5%–72% of men following radical prostatectomy alone,[12,13] 0%–10% following high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU),[14,15] and 0%–14% following radiotherapy alone.[16]

There is controversy as to whether neoadjuvant or adjuvant radiotherapy adversely affects the functional outcome of the AUS in men who have had treatment for prostate cancer. Resnick et al. reported no significant difference in the odds of urinary incontinence between irradiated and nonirradiated patients 15 years posttreatment.[17] This is supported by Ravier et al.,[18] Sathianathen et al.,[19] and other studies showing similar findings.[20,21] Conflicting evidence was detailed in the studies by Pérez et al.[22] and Walsh et al.[23] who found worse continence rates in patients who received radiotherapy before AUS. Indeed, Bates et al.[8] in a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 949 patients concluded that persistent urinary incontinence is more common in men having radical prostatectomy and radiotherapy than those having radical prostatectomy alone.

We have assessed the outcomes and complications of men having bulbar AUS for SUI following treatment of prostate cancer to determine whether radiotherapy affects continence outcomes

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We have retrospectively reviewed our prospectively acquired database of all patients having an AUS insertion between the years 2002 and 2012. The dermographic data, mode of prostate cancer treatment(s) and continence outcomes following AUS implantation were assessed.

A total of 184 men had an AUS implanted in this period. Of these, 58 had bulbar AUS implanted for SUI consequent to the treatment of their prostate cancer. Of the 21 (36%) irradiated patients, 19 were treated initially with radical prostatectomy and 2 had external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) as sole therapy. Of the remaining 37 patients, 35 were treated solely with radical prostatectomy and 2 had HIFU.

All bulbar AUS implantations (primary and revision) in a uniform manner during the study period using proximal-mid bulbar extracorporeal cuff placement, iliac fossa extraperitoneal balloon placement, and subdartos pouch control pump location. No cuff size smaller than 4.0 cm was used and all had a 61–70 cm H2O pressure regulating balloon. Standard preoperative assessment was carried out for each patient including a midstream urine sample to exclude active infection as well as video-urodynamic assessment. All AUS were activated 6 weeks postoperatively (Do we have data on capacity, etc.).

Patients were followed up by a consultation 3 months postoperatively and annually thereafter. The initial consultation included a physical examination and evaluation of clinical outcomes in terms of continence and patient satisfaction. Complete continence was defined as being dry without the use of any pads (pad free, leak free) by both patient and clinician.

Statistical analyses were performed by Chi-squared and Fischer's exact tests. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

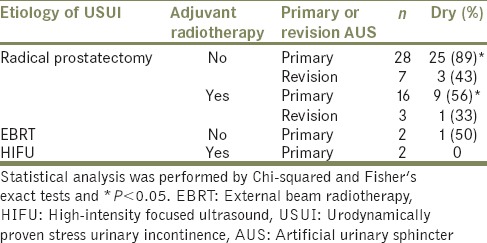

The median duration of follow-up post-AUS activation was 19 months (1–119). The patient cohort was divided into two groups: those having primary implantation of AUS versus those having a revision procedure [Table 1].

Table 1.

Outcomes in irradiated versus nonirradiated patients, in the primary and revision settings

A total of 48 (83%) patients had a primary bulbar AUS implantation during this period. Twenty-eight of these patients had had radical prostatectomy as their only prostate cancer treatment and 25 (89%) achieved complete continence following AUS implantation. Sixteen patients had their prostate cancer treated with adjuvant radiotherapy due to biochemical failure following radical prostatectomy and only 9 (56%) were completely continent following AUS implantation. This was a statistically significantly lower complete continence rate than in the nonirradiated group (P < 0.05) [Table 1].

Ten patients had a second bulbar AUS implanted as a revision procedure during the study period. Seven had their prostate cancer treated with radical prostatectomy alone. Three (43%) of these men achieved complete continence. Three men had adjuvant radiotherapy following radical prostatectomy for the treatment of their prostate cancer and only 1 (33%) was completely continent post-AUS implantation.

Two patients were treated with EBRT only. One (50%) was completely continent post-AUS insertion. Neither of the two patients treated with HIFU achieved continence.

DISCUSSION

Radiotherapy was associated with significantly lower complete continence rates in all AUS patients and primary AUS patients in particular. Repeat AUS implantation was associated with poorer continence outcomes than primary AUS implantation.

SUI following treatment for prostate cancer causes significant negative impact on quality of life (QOL). Implantation of a bulbar AUS is the gold standard treatment for SUI in this situation, providing high rates of long-term continence and acceptable morbidity. The effect of adjuvant radiotherapy on the outcomes of AUS implantation is still undecided. Several studies report conflicting results. While Jhavar et al. concluded that prior radiation did not alter AUS postoperative outcomes,[24] Suardi et al. reported that at 1 and 3 years after adjuvant radiotherapy, urinary continence recovery was 51% and 59% as opposed to 81% and 87% for those not receiving adjuvant radiotherapy.[25] This is confirmed in the reports of higher rates of persistent urinary incontinence post-AUS implantation in those men treated with adjuvant and neoadjuvant radiotherapy, with rates ranging from 5% to 48%.[19,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]

Radiation causes ischemic fibrosis of the urethra resulting in hypovascularity and subsequent tissue atrophy. As a consequence, irradiated patients exhibit a higher incidence of urethral stricture disease.[19,23] Sathianathen et al. reported a urethral stricture rate of 62.1% in irradiated patients compared with only 10.4% in the nonirradiated surgery only group.[19] If radiation is sufficient to cause ischemia and fibrosis in the region of the bladder neck, it does not require too much of an extension of thought and irradiation field for it to cause similar effects on the bladder – producing the adverse continence outcomes described in our and other studies and confirmed in Bates et al's meta-analysis.[8]

Persistent urinary incontinence following AUS implantation may not be consequent to persistent intrinsic sphincter deficiency secondary but due to bladder factors such as de novo detrusor overactivity, loss of compliance, or loss of capacity.[26,27,28] All which are known to occur following radiotherapy to the bladder. The variation in continence outcomes described in the literature is consequent to variation in radiotherapy dose and techniques, patient selection bias, and variation in the definition of continence, outcomes measures and follow-up.

High complication rates with AUS implantation in irradiated patients have been reported by Manunta et al., with 8 of 15 patients with pelvic radiation requiring further surgical intervention.[23] Other studies have also reported increased rates of postoperative complications and surgical revision rates after adjuvant radiotherapy.[8,27] Conversely, surgical revision rates are not uniformly low in nonirradiated patient cohorts. Reports vary widely, ranging from 5% to 40%.[2,23,28,29,30,31,32,33,34] The varying rates may well be due to small cohort numbers, incomplete data, and/or inconsistent follow-up particularly with patient satisfaction and QOL questionnaires. Certainly, the surgical revision rates reported for irradiated patients are consistently higher than those in nonirradiated patients. This is well demonstrated in Bates et al's meta-analysis of 15 studies, where the reported surgical revision rates in the irradiated group are 37.3% ± 6.1%, whereas those for the nonirradiated group were 19.8% ± 3.6% at 95% confidence intervals, respectively. Urethral atrophy accounted for 36.7% ± 10.9% and infection and erosion accounted for 52.3% ± 10.6% of surgical revisions.[8]

CONCLUSION

The bulbar AUS remains the gold standard for the treatment of postprostatectomy SUI making 89% of men with SUI following radical prostatectomy only dry on primary insertion. Results for men treated with both radical prostatectomy and radiotherapy are not as good, with only 56% of men becoming dry following AUS implantation. All men, regardless of their prostate cancer treatment modality, having repeat AUS implantation do not have as satisfactory continence outcomes as those having primary AUS implantation. Care should be taken when managing and counseling those who have received radiotherapy as well as surgery and those having repeat procedures.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Milsom I, Coyne KS, Nicholson S, Kvasz M, Chen CI, Wein AJ. Global prevalence and economic burden of urgency urinary incontinence: A systematic review. Eur Urol. 2014;65:79–95. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coyne KS, Wein A, Nicholson S, Kvasz M, Chen CI, Milsom I. Economic burden of urgency urinary incontinence in the United States: A systematic review. J Manag Care Pharm. 2014;20:130–40. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.2.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El Fegoun AB, Barret E, Prapotnich D, Soon S, Cathelineau X, Rozet F, et al. Focal therapy with high-intensity focused ultrasound for prostate cancer in the elderly. A feasibility study with 10 years follow-up. Int Braz J Urol. 2011;37:213–9. doi: 10.1590/s1677-55382011000200008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guillaumier S, McCartan N, Dickinson L, Fatola Y, Freeman H, Hindley R, et al. Does focal high-intensity focused ultrasound have a role in treating localized prostate cancer in the elderly? J Clin Onccol. 2015;33:7. Supplement 1. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Retornaz F, Seux V, Pauly V, Soubeyrand J. Geriatric assessment and care for older cancer inpatients admitted in acute care for elders unit. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;68:165–71. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ficarra V, Novara G, Rosen RC, Artibani W, Carroll PR, Costello A, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of studies reporting urinary continence recovery after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2012;62:405–17. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hussain M, Greenwell TJ, Venn SN, Mundy AR. The current role of the artificial urinary sphincter for the treatment of urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2005;174:418–24. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000165345.11199.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bates AS, Martin RM, Terry TR. Complications following artificial urinary sphincter placement after radical prostatectomy and radiotherapy: A meta-analysis. BJU Int. 2015;116:623–33. doi: 10.1111/bju.13048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gousse AE, Madjar S, Lambert MM, Fishman IJ. Artificial urinary sphincter for post-radical prostatectomy urinary incontinence: Long-term subjective results. J Urol. 2001;166:1755–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fowler FJ, Jr, Barry MJ, Lu-Yao G, Roman A, Wasson J, Wennberg JE. Patient-reported complications and follow-up treatment after radical prostatectomy. The National Medicare Experience: 1988-1990 (updated June 1993) Urology. 1993;42:622–9. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(93)90524-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steiner MS, Morton RA, Walsh PC. Impact of anatomical radical prostatectomy on urinary continence. J Urol. 1991;145:512–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38382-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Litwiller SE, Kim KB, Fone PD, White RW, Stone AR. Post-prostatectomy incontinence and the artificial urinary sphincter: A long-term study of patient satisfaction and criteria for success. J Urol. 1996;156:1975–80. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)65408-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stanford JL, Feng Z, Hamilton AS, Gilliland FD, Stephenson RA, Eley JW, et al. Urinary and sexual function after radical prostatectomy for clinically localized prostate cancer: The Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. JAMA. 2000;283:354–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.3.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uddin Ahmed H, Cathcart P, Chalasani V, Williams A, McCartan N, Freeman A, et al. Whole-gland salvage high-intensity focused ultrasound therapy for localized prostate cancer recurrence after external beam radiation therapy. Cancer. 2012;118:3071–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yap T, Ahmed HU, Hindley RG, Guillaumier S, McCartan N, Dickinson L, et al. The effects of focal therapy for prostate cancer on sexual function: A combined analysis of three prospective trials. Eur Urol. 2016;69:844–51. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lilleby W, Stensvold A, Dahl AA. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy to the pelvis and androgen deprivation in men with locally advanced prostate cancer: A study of adverse effects and their relation to quality of life. Prostate. 2013;73:1038–47. doi: 10.1002/pros.22651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Resnick MJ, Koyama T, Fan KH, Albertsen PC, Goodman M, Hamilton AS, et al. Long-term functional outcomes after treatment for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:436–45. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ravier E, Fassi-Fehri H, Crouzet S, Gelet A, Abid N, Martin X. Complications after artificial urinary sphincter implantation in patients with or without prior radiotherapy. BJU Int. 2015;115:300–7. doi: 10.1111/bju.12777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sathianathen NJ, McGuigan SM, Moon DA. Outcomes of artificial urinary sphincter implantation in the irradiated patient. BJU Int. 2014;113:636–41. doi: 10.1111/bju.12518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fridriksson Jí, Folkvaljon Y, Nilsson P, Robinson D, Franck-Lissbrant I, et al. Long-term adverse effects after curative radiotherapy and radical prostatectomy: Population-based nationwide register study. Scand J Urol. 2016;50:338–45. doi: 10.1080/21681805.2016.1194460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elliott DS, Barrett DM. Mayo clinic long-term analysis of the functional durability of the AMS 800 artificial urinary sphincter: A review of 323 cases. J Urol. 1998;159:1206–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pérez LM, Webster GD. Successful outcome of artificial urinary sphincters in men with post-prostatectomy urinary incontinence despite adverse implantation features. J Urol. 1992;148:1166–70. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36850-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walsh IK, Williams SG, Mahendra V, Nambirajan T, Stone AR. Artificial urinary sphincter implantation in the irradiated patient: Safety, efficacy and satisfaction. BJU Int. 2002;89:364–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-4096.2001.01759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jhavar S, Swanson G, Deb N, Littlejohn L, Pruszynski J, Machen G, et al. Durability of artificial urinary sphincter with prior radiation therapy. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2017;15:e175–80. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2016.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suardi N, Gallina A, Lista G, Gandaglia G, Abdollah F, Capitanio U, et al. Impact of adjuvant radiation therapy on urinary continence recovery after radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2014;65:546–51. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manunta A, Guillé F, Patard JJ, Lobel B. Artificial sphincter insertion after radiotherapy: Is it worthwhile? BJU Int. 2000;85:490–2. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lilleby W, Fosså SD, Waehre HR, Olsen DR. Long-term morbidity and quality of life in patients with localized prostate cancer undergoing definitive radiotherapy or radical prostatectomy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;43:735–43. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00475-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Emirdar V, Nayki U, Ertas IE, Nayki C, Kulhan M, Yildirim Y. Urodynamic assessment of short-term effects of pelvic radiotherapy on bladder function in patients with gynecologic cancers. Ginekol Pol. 2016;87:552–8. doi: 10.5603/GP.2016.0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai HH, Hsu EI, Teh BS, Butler EB, Boone TB. 13 years of experience with artificial urinary sphincter implantation at Baylor College of Medicine. J Urol. 2007;177:1021–5. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cambio AJ, Evans CP. Minimising postoperative incontinence following radical prostatectomy: Considerations and evidence. Eur Urol. 2006;50:903–13. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gomha MA, Boone TB. Artificial urinary sphincter for post-prostatectomy incontinence in men who had prior radiotherapy: A risk and outcome analysis. J Urol. 2002;167(2 Pt 1):591–6. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)69091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martins FE, Boyd SD. Artificial urinary sphincter in patients following major pelvic surgery and/or radiotherapy: Are they less favorable candidates? J Uro. 1995;18:1188–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raj GV, Peterson AC, Webster GD. Outcomes following erosions of the artificial urinary sphincter. J Urol. 2006;175:2186–90. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(06)00307-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aaronson DS, Elliott SP, McAninch JW. Transcorporal artificial urinary sphincter placement for incontinence in high-risk patients after treatment of prostate cancer. Urology. 2008;72:825–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.06.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]