Abstract

Objective:

Surgical management of giant skull osteomas Osteomas are benign, generally slow growing, bone forming tumors limited to the craniofacial and jaw bones.

Materials and Methods:

A retrospective review of all cases of osteoma diagnosed from 2009 to 2013 treated in our hospital. The data collected included age at diagnosis, gender, lesion location, size, presenting and duration of symptoms, treatment, complication and outcome.

Results:

During our study period there were 15 cases that were treated surgically. Their mean age was 42 years (range: 15–65 years) and all of our patients were female. The average duration of symptoms was 3 years and size varying from 4 cm to 12 cm. Eight patients complained of headache, whereas 6 patients complained about esthetics, and 1 patient presented with proptosis. The tumor was excised by cutting the base of the tumor and then residual tumor was grinded using a round head cutting bar. Osteoma was removed with esthetically acceptable appearance.

Conclusion:

There were no major complications during operative and postoperative period. Although osteomas are usually slow growing but surgery is usually performed due to esthetic reasons. It is important to plan an appropriate surgical approach that minimizes any damage to the adjacent structures.

Keywords: Craniectomy, giant osteoma, histopathology

Introduction

Osteomas are the most common of the primary benign bone tumors of the skull and facial structures. They can be subdivided into bone surface tumors (or exostoses) that primarily involve the cranial vault, mandible, and external auditory canal and the more common sino-orbital (or paranasal sinus) osteomas that arise from bones that define the paranasal sinuses, nasal cavity, and orbit.[1,2] Osteomas are mainly asymptomatic and account for 0.43% of tumor in the general population with an incidental finding on 1% of plain radiographs and on 3% of computed tomography (CT) scans.[1]

Osteomas have a tendency to grow slowly and therefore these tumors are usually asymptomatic. Tumor size, location, and extension determine the clinical manifestations. These solid nodular schlerotic lesion usually arise from the outer table and are usually < 10 mm but lesions larger than 30 mm in diameter are considered giant tumors.[3,4]

The aim of this study is to retrospectively evaluate patients who had giant skull osteomas and to analyze the clinical, radiological, and surgical aspects of these lesions.

Materials and Methods

Patient population

Between 2009 and 2013, 15 consecutive patients with giant osteomas were treated surgically in our department. The patient population consisted of adult female patients ranging in age from 15 to 65 years (mean 42 years) with giant cranial osteomas involving the cranial vault and some with extension into the paranasal sinuses or orbital wall.

Imaging features

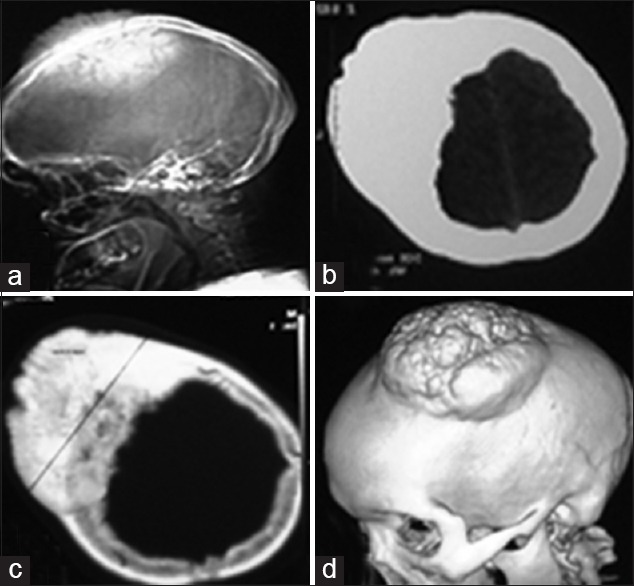

All patients underwent neurological and radiological evaluation in the preoperative period, including: Plain radiographs; head CT scans; and also three-dimensional (3D) cranial CT [Figure 1]. The thickness and dimensions of each osteoma were measured along with the origin and its extension.

Figure 1.

(a) Plain lateral radiograph showing osteoma in the frontoparietal region. (b) Non contrast computed tomography (CT) scan section showing hyperdense area on the right frontoparietal bone. (c) CT scan bone window showing excessive bone hyperthropy. (d) Three dimensional reconstruction showing giant osteoma on left parietal region

Results

Patient characteristics and tumor features

Fifteen patients underwent surgical excision for giant osteomas of the skull during 4 years period. The study population consisted of 15 women with median age of 42 years (range: 15–65 years). None of these patients were known to have Gardner syndrome. Frontal portion of the skull was the most common primary site (60%), followed by frontoparietal (13%) and temporoparietal (6%) concomitantly making it impossible to determine a single site of origin. There was one each with temporal and occipital osteoma. Four patients had orbital roof involvement and two others had infiltration into the sphenoid sinus [Table 1].

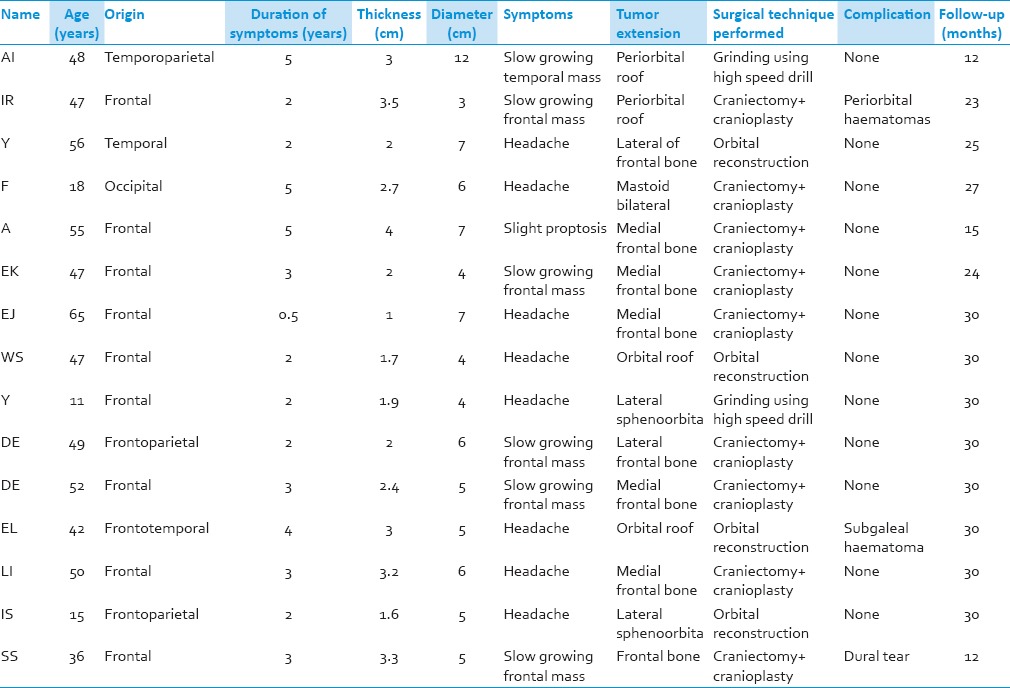

Table 1.

Summary of patient characteristic and tumor features

Operative findings

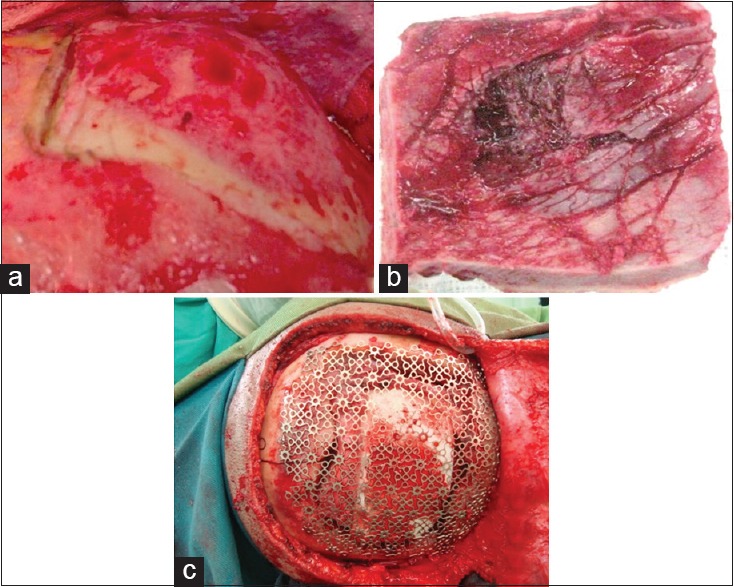

Surgery was performed in all patients under general anethesia. The type of surgery selected was based on location, tumor size, extension and relationship to underlying brain tissue, duramater, and involvement of paranasal or orbital structures. Removal of the bone mass was done via craniectomy and followed by cranioplasty using methyl methacrylate or titanium mesh [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

(a) Large osteoma in the right frontal bone. (b) Photograph showing the osteoma that was completely resected. (c) Titanium mesh applied over the resected bone

In patients with sino-orbital extension, a malleable retractor was placed under the orbital roof to prevent the drill or osteotome from damaging the orbital contents. The sinuses were successfully cleaned and exenterated of mucosal lining. The sinuses were routinely covered with a pericranial flap to isolate them from the epidural space. Once the osteoma was removed, cranial and/or orbital reconstruction was initiated. In some cases total resection was not achieved due to important nearby structures. In these cases we performed grinding of the skull with a round head cutting bar. There were no major complications during the intraoperative period with only one dural tear from 15 patients. This was due to the adherent dura attached with the large tumor. We found dural tear in 1 patient during surgery and we performed duroplasty.

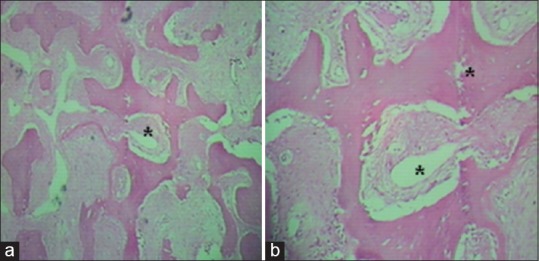

Pathological findings

Sections of the bone showed a solid tumor composed of compact osteoid lamina without marrow components. The tumor consisted of homogeneous bony structures with the cortical substance. There was no nuclear atypia noted nor any abnormality in the surrounding bone and soft tissue. Histopathology report revealed compact trabeculae of lamellar bone with a variable amount of osteoid and prominent cement lines consistent with osteoma [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

(a) Histopathologic image of osteoma (H and E, ×10) showing dense lamellae with organized haversian canals (*) and (b) the intratrabecular stroma contains osteoblasts, fibroblasts, and giant cells, with no hematopoietic cells

Postoperative follow-up

All patients received antibiotics routinely for at least 3 days after the operation to prevent skin infection. The patients were monitored for hemodynamic changes and possible cerebrospinal fluid leaks secondary to dural tear. CT scans were performed in the early postoperative period as a routine procedure. Complications such as hemorrhage, ocular disturbance, loss of vision, or cerebrospinal fluid fistulas were not seen in our series. Mild postoperative periorbital ecchymosis and subgaleal hematoma was noted in 1 patient each which was managed conservatively and fully resolved. None of the patients had any postoperative morbidity and the physical examination results were normal in all patients at the end of the follow-up period. No recurrence or residual osseous tumor was observed on plain radiographs and CT scans in any patient during this period.

Most of our patients had headache (8 patients, 53%) followed by esthetic complaint of a large slowly growing mass on their skull (40%) and one patient complained of proptosis (7%). The median duration of the preoperative tumor growth period, from the time the osteoma was perceivable by the patient was 3 years (range: 6 months and 5 years). The mean diameter of the osteomas was 10 cm (range: 3–12 cm).

Discussion

Osteomas have a predilection for the head and neck region which includes the facial bones, skull, and mandible and is the most common benign tumour of the sinonasal tract.[5] Osteomas are slow growing tumours consisting entirely of well differentiated bone. They are subdivided in ivory and mature types depending on the proportions of dense and cancellous bone. Ivory osteomas are composed of dense, mature, lamellar bone with little fibrous stroma. Mature osteomas are composed of large trabeculae of mature, lamellar bone with more abundant fibrous stroma and may or may not have osteoblastic rimming. Tumors with both ivory and mature features are described as mixed type.[2]

Haddad et al. have classified cranial osteomas into four types: Intraparenchymal; dural; skull base; and skull vault. Intraparenchymal osteomas have no connection to dura or bone, are the rarest type. Dural osteomas have no bony attachment, arise mainly from the falx, are asymptomatic and are often incidental findings on plain radiographs. Skull base osteomas are most common in the frontal sinus, but may also occur in the ethmoid air cells, maxillary and sphenoid sinuses, the maxilla and mandible and occasionally arise in the temporal bone. They are rarely symptomatic but may be the cause of headaches, orbital invasion and deformity, pneumocephalus, rhinorrhea, meningitis and abscess. Skull vault osteomas may arise from the outer table (exostotic) or inner table (enostotic), and are usually asymptomatic.[4]

The pathogenesis of osteomas is controversial. Three theories were identified, namely embryologic, infectious and traumatic. In the embriologic theory, it is assumed that osteomas originate from periostal embryologic cells or embryologic cartilage cells at the junction of cranial vault bones. Infections as tuberculosis, syphilis and sinus drainage disfunction supports infectious theory. In the traumatic theory, a head trauma is usually found in patient's history. In 30% of osteoma cases, history of head trauma is found. According to some authors, posttraumatic physiological changes and inflammation may trigger metaplastic processes of osteogenic cells.[6,7] In all of our case, there was no trauma and infection.

It has also been reported that imaging of the osteomas can be achieved by traditional radiography or CT scan. The use of CT scanning with 3D reconstruction makes it possible to achieve a better visualization and more precise localization. On a CT scan osteomas may present as demarcated and hyperdense outgrowths of the bone as seen in our series. Axial, coronal and sagital scans together demonstrate the exact dimension of osteomas.[8]

The growth rate of an osteoma is very slow, from 12 to 30 years according to reported series, even though after incomplete excision, relapse may occur after 2–8 years.[1] The median duration of the preoperative tumor growth period in our cases was 3 years. Osteomas are treated by surgical resection or clinical follow-up. Its surgical indication depends upon several factors amongst which the extension volume, symptomatology and complications are most important. When small and asymptomatic they are submitted to conservative treatment, clinically monitored and followed-up with CT, and in cases of constant pain, neurological symptoms and extension to adjacent structure or esthetic alterations, the surgical approach is indicated.[1,4] The treatment generally consists of en bloc resection or grinding of the tumor using a high-speed drill. For large orbitocranial osteomas, combining the craniotomy with an orbitotomy makes a single-stage radical excision possible.[1]

Conclusion

Osteomas are benign lesions which are generally asymptomatic but for symptomatic lesions, surgical removal is the treatment of choice. The adhesion of the surrounding brain tissue and vascular structures should be taken into consideration during the radical excision of the large sized tumors.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Secer HI, Gonul E, Izci Y. Surgical management and outcome of large orbitocranial osteomas. J Neurosurg. 2008;109:472–7. doi: 10.3171/JNS/2008/109/9/0472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McHugh JB, Mukherji SK, Lucas DR. Sino-orbital osteoma: A clinicopathologic study of 45 surgically treated cases with emphasis on tumors with osteoblastoma-like features. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1587–93. doi: 10.5858/133.10.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erten F, Hasturk AE, Pak I, Sokmen O. Giant occipital osteoid osteoma mimicking calcified meningioma. Neurosciences (Riyadh) 2011;16:363–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haddad FS, Haddad GF, Zaatari G. Cranial osteomas: Their classification and management. Report on a giant osteoma and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 1997;48:143–7. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(96)00485-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu SC, Su WF, Nieh S, Lin DS, Chu YH. Lingual osteoma. J Med Sci. 2010;30:97–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shigehara H, Honda Y, Kishi K, Sugimoto T. Radiographic and morphologic studies of multiple miliary osteomas of cadaver skin. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;86:121–5. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cece H, Yildiz S, Iynen I, Karakas O, Karakas E, Dogan F. A rare case of petrous apex osteoma. J Pak Med Assoc. 2012;62:608–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castelino RL, Babu SG, Shetty SR, Rao KA. Multiple craniofacial osetomas: An isolated case. Arch Orofac Sci. 2011;6:32–6. [Google Scholar]