Abstract

Stakeholder engagement is an emerging field with little evidence to inform best practices. Guidelines are needed to improve the quality of research on stakeholder engagement through more intentional planning, evaluation and reporting. We developed a preliminary framework for planning, evaluating and reporting stakeholder engagement, informed by published conceptual models and recommendations and then refined through our own stakeholder engagement experience. Our proposed exploratory framework highlights contexts and processes to be addressed in planning stakeholder engagement, and potential immediate, intermediate and long-term outcomes that warrant evaluation. We use this framework to illustrate both the minimum information needed for reporting stakeholder-engaged research and the comprehensive detail needed for reporting research on stakeholder engagement.

Keywords: : conceptual model, dissemination, evaluation, reporting, stakeholder-engaged, stakeholder engagement, transparency

Stakeholder engagement in research aims to improve research quality through the incorporation of multiple perspectives beyond the traditional research team in the planning and execution of studies. In this context, stakeholders can be defined as “an individual or group who is responsible for or affected by health- and healthcare-related decisions that can be informed by research evidence” [1]. While there is growing financial and theoretical support for stakeholder engagement, the actual impact of such engagement has not been well established. Systematic reviews have found that data on the impact of stakeholder engagement are generally qualitative and limited [2,3], and advancing this literature is hindered by lack of consensus regarding terminology and concepts for reporting stakeholder engagement processes and outcomes [2,3]. Thus, there is a need to build the evidence surrounding stakeholder engagement, but no clear, unified roadmap to guide researchers seeking to do so.

To strengthen the emerging literature on stakeholder engagement, we propose that there is a need to first distinguish between two related but distinct areas of inquiry: research that aims to address questions while engaging stakeholders (stakeholder-engaged research) and research that aims to address questions about engaging stakeholders (research on stakeholder engagement). The latter – studies that specifically document and evaluate stakeholder engagement processes – aim to study the methods of engaging stakeholders. Such work is needed to document the impact of stakeholder engagement and provide guidance on best practices. In contrast, the former – studies that incorporate stakeholders while completing other aims – use stakeholder engagement in their research but do not seek to directly advance the methodology of stakeholder engagement. Thus in a given study, the research objective determines whether the work is research on stakeholder engagement or stakeholder-engaged research. Investigators reporting stakeholder-engaged research must describe their stakeholder engagement methods clearly and concisely, as is expected for reporting any research method. Investigators reporting research on stakeholder engagement must provide even greater detail, given that stakeholder engagement is the object of their study rather than a tool for conducting the study.

To improve stakeholder engagement, multiple frameworks for conceptualizing, planning and/or evaluating stakeholder engagement have been proposed, focusing to different degrees on processes of engagement, potential impacts of engagement and underlying values of engagement [1–24]. These studies offer valuable insights into stakeholder engagement, but none provide a comprehensive framework to guide researchers through the full process of planning, evaluating and reporting stakeholder engagement. Several of these publications highlight proposed ‘best practices’ for stakeholder engagement. For example, the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute Patient and Family Engagement Rubric emphasizes six engagement principles in planning stakeholder engagement: reciprocal relationships, co-learning, partnerships, transparency, honesty and trust [4]. As another example, Hoffman et al. emphasized five best practices of stakeholder engagement for comparative effectiveness studies: balanced representation (through attention to the number and participation of different stakeholders), stakeholder's acceptance of roles, use of expert facilitators, building connection among stakeholders and sustained engagement [5]. These two lists highlight important concepts in stakeholder engagement, but also illustrate issues with this literature: multiple partially overlapping recommendations across different sources; different terms used for the same or overlapping concepts (reciprocal relationships vs stakeholder's acceptance of roles); and lists containing values to strive for (trust) versus actionable advice (expert facilitation). Additionally, such best practices publications are often most relevant for planning stakeholder-engaged research and may omit discussion of evaluating or reporting stakeholder engagement. Overall, articles addressing best practices identify many key concepts specific to planning stakeholder engagement. None provide explicit guidance on reporting and evaluating the stakeholder engagement process itself. Thus, we attempted to synthesize key insights from this emerging literature on stakeholder engagement to strengthen the planning, evaluating and reporting of stakeholder engagement.

Another set of publications have sought to evaluate the impact of stakeholder engagement, aligning more closely with research on stakeholder engagement. These authors provide valuable summaries of theoretical impacts of stakeholder engagement, and illustrate the paucity of data about these impacts. For example, Esmail et al. offer a synthesis of hypothetical impact of stakeholder engagement and the limited qualitative and quantitative assessments of these impacts [2]. Such impacts range from better quality research and increased uptake of results to patient empowerment and moral obligation [2]. As another example, Lavallee et al. focus on evaluating stakeholder engagement through six meta-criteria: trust, respect, fairness, legitimacy, competence and accountability [6]. As with published best practice guidelines, these proposed sets of criteria for evaluating stakeholder engagement include partially overlapping lists, different terms representing similar or partially overlapping concepts (moral obligation vs fairness), and a mix of values (trust) and objective outcomes (increased uptake of results). Thus, these and other evaluation studies offer valuable catalogs of potential impacts of stakeholder engagement, but may be difficult to use to guide planning, evaluation and reporting without further synthesis.

Finally, there are a limited number of studies with specific recommendations on reporting stakeholder engagement. Concannon et al. published a seven-item questionnaire with the goal of improving quality and content of reporting on stakeholder engagement [3]. Questions include: “what type of stakeholders were engaged?”; “how was balance of stakeholder perspectives considered?”; and “what was the intensity, methods and modes of engagement?” [3]. These questions cover aspects of stakeholder engagement necessary for communicating about stakeholder engagement, but omit other topics that may be needed to advance research on stakeholder engagement, such as the contexts of engagement, methodologic changes due to stakeholders and the stakeholder experience. Additionally, authors may not be able to answer all of these questions at the time of publication, as assessing the impact of engagement on uptake of findings may require observation after dissemination efforts. Guise et al. published a checklist for planning and reporting stakeholder engagement for the purpose of prioritizing research topics [7]. While being valuable for this specific purpose, the checklist is less well suited to other types of stakeholder-engaged research or to research on stakeholder engagement. Altogether, these prior studies identified important concepts for planning and examining stakeholder engagement, but the variation in focus (planning vs evaluating vs reporting) and terminology necessitate further synthesis for those seeking guidance from this prior work. In particular, while prior work establishes the need for high-quality research on stakeholder engagement [2,3], the few available reporting guidelines [3,7] are most relevant for strengthening stakeholder-engaged research.

To accelerate the development of generalized knowledge regarding stakeholder engagement, the objective of this work was to develop a comprehensive framework of concepts relevant to stakeholder engagement planning, evaluation and reporting, and to illustrate different evaluation and reporting needs for research on stakeholder engagement as compared with stakeholder-engaged research. Drawing from prior work [1–24] and subsequently refined through our experience, we propose a conceptual model illustrating the hypothesized impacts of stakeholder engagement. To provide guidance for those planning, evaluating and reporting both types of research, we then propose a framework for planning and reporting both stakeholder-engaged research and research on stakeholder engagement. To help distinguish between describing stakeholder-engaged research and reporting research on stakeholder engagement, we applied this framework to our experience engaging stakeholders, offering both a minimal report of our stakeholder-engaged research and a comprehensive report of our research on stakeholder engagement. In this way, we aim to advance the rigor and transparency of stakeholder engagement to more rapidly improve best practices in the field.

Methods

Conceptual model

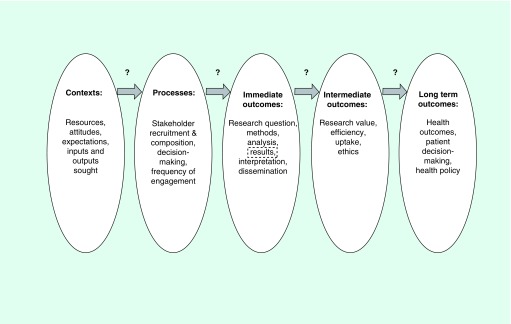

We developed a conceptual model of the potential impact of stakeholder engagement (Figure 1) based on synthesis of prior work [1–24]. This model illustrates the hypothesized relationship between contexts (resources or decisions external to but informing engagement process), processes (actions of actual engagement) and outcomes of stakeholder engagement. Proposed outcomes drawn from prior work were further divided into immediate (related to the specific project), intermediate (related to the research output) and long-term goals (related to health decisions and health outcomes) of the engagement process. This model suggests that impact on long-term outcomes must be achieved through impact on immediate and intermediate outcomes to attribute the long-term outcomes to the stakeholder engagement process. For example, stakeholder engagement might ultimately allow patients to make more informed decisions (long-term outcomes), but we hypothesize that this will occur via an intermediate outcome (e.g., improved uptake of research), which would in turn occur through an immediate outcome (e.g., changes in the research question or methodology). Within the model, we highlight the different focus on stakeholder-engaged research (dashed box) compared with research on stakeholder engagement (question marks).

Figure 1. . Conceptual model for understanding impact of stakeholder engagement and differentiating stakeholder-engaged research from research on stakeholder engagement.

Dashed box (- - -) indicates the focus on stakeholder-engaged research, which is the result of the study being informed by stakeholders. Question marks (?) indicate the focus of research on stakeholder engagement, which is the relationship between the contexts, processes and outcomes of stakeholder engagement. Please see Table 1 for additional detail on topics/concepts within the model.

Preliminary reporting framework development

Building on the broad categories of contexts, processes and outcomes in our conceptual model, we synthesized prior work on best practices, evaluation and reporting [1–24] identified through a targeted review to develop a preliminary framework for planning, evaluating and reporting both research on stakeholder engagement and stakeholder-engaged research. We then refined this framework through the process of planning, evaluating and reporting our stakeholder engagement experience, resulting in the proposed framework (Table 1).

Table 1. . Contexts, processes and outcomes for planning, evaluating and reporting stakeholder engagement.

| Topic | Subtopic | Planning stakeholder-engaged research and research on stakeholder engagement | Minimum reporting (stakeholder-engaged research) | Comprehensive reporting (research on stakeholder engagement) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1. Contexts† | ||||

| Resources available |

Funding, time, expertise of researchers and stakeholders, training for researchers and stakeholders |

X |

|

X |

| Attitudes and expectations |

Commitment to and attitudes toward engagement from researchers and stakeholders |

X |

|

X |

| Desired input from stakeholders |

Values, knowledge and experience sought |

X |

X |

X |

| Desired goals of engagement |

Decisions to be deliberated with stakeholders and goals of engagement |

X |

X |

X |

|

2. Processes† | ||||

| Stakeholder recruitment |

Identification and outreach to potential stakeholders; recruitment rate |

X |

X |

X |

| Stakeholder composition |

Diversity, composition |

X |

X |

X |

| Setting expectations |

How expectations were communicated; introductions; stakeholder understanding of roles and expectations; agenda-setting for specific meetings; establishment of reciprocal relationships; establishment of power sharing |

X |

|

X |

| Decision making |

Structured decision making, use of appropriate quantitative/qualitative methods, use of facilitators; stakeholder experience of decision making |

X |

|

X |

| Frequency and duration of engagement |

Timing, duration, method, frequency, flexibility and methods of interactions Options for stakeholder-initiated interaction Ongoing/sustained engagement vs more limited engagement |

X |

X |

X |

| Representativeness |

Balanced representation and participation Group decision making |

X |

|

X |

| Co-learning |

Two-way sharing of information and background to allow meaningful contribution and conversation; use of written or visual materials; avoiding jargon |

X |

|

X |

| Valuing stakeholder contribution |

Thoughtful and transparent requests for time commitment; financial compensation |

X |

|

X |

| Transparency |

Transparent engagement processes and rationale Feedback given to stakeholders about their input and impact Final products for dissemination shared |

X |

|

X |

|

3. Outcomes | ||||

| Immediate outcomes:‡ | X | |||

| – Changes in project scope | Defining/prioritizing topic, question, hypotheses, intervention, outcomes to be measured | X | X | |

| – Changes in project methods | Design, methods, recruitment, data collection | X | X | |

| – Changes in interpretation | Analysis, interpretation, synthesis; anticipating alternative interpretation or controversy | X | X | |

| – Changes in dissemination plans |

Content and method of distribution |

|

X |

X |

| – Changes in future directions |

Follow-up projects, collaborations, funding |

|

X |

X |

| – Changes in future engagement |

Researcher knowledge, capacity, commitment to engagement; Continued/new stakeholder involvement |

|

X |

X |

| – Stakeholder satisfaction |

Satisfaction, continued involvement |

|

|

X |

| Intermediate outcomes:‡ | X | X | ||

| – Value of evidence generated | Quality, applicability, alignment with stakeholder priorities, alignment with stakeholder decision making | § | ||

| – Efficiency of research efforts | Improved recruitment, retention, inclusivity. Improved data collection procedures. Timeliness of publication and dissemination | § | ||

| – Uptake of research | Improved translation, dissemination and uptake, potentially through increased perceived legitimacy/accountability; increased relevance/quality and/or increased attention to dissemination activities | § | ||

| – Improved ethics of research | Design/process more appropriate, inclusive, sensitive and ethical | § | ||

| – Empowerment of patients/stakeholders |

Stakeholder participant attitudes or actions suggesting increased engagement and efficacy with research and/or healthcare system |

|

|

§ |

| Creation/sustaining of partnerships |

Creating and maintaining partnerships with stakeholders, facilitating stakeholder engagement in ongoing/future work |

|

|

§ |

| Long-term outcomes:‡ | X | X | ||

| – Improved patient decision making | Improvement in ability of data to answer questions informing patient's decisions | § | ||

| – Improved clinical/health policy decision making | Improvement in ability of data to answer questions informing clinician or policy-maker's decisions | § | ||

| – Improved health outcomes | Improvement in patient-centered health outcomes | § | ||

| – Improved culture of research | Improved accountability, inclusivity, trust, ethics | § | ||

†When relevant, consider distinguishing between planned and actual contexts, processes and outcomes, particularly for research on stakeholder engagement.

‡Planning efforts for both stakeholder-engaged research and research on stakeholder engagement should consider the evaluation of immediate, intermediate and long-term outcomes, even if not all are evaluated.

§In research on stakeholder engagement, not every intermediate and long-term outcome will be assessed, but the full range of outcomes should be considered for assessment. We recommend acknowledging missing outcomes or groups of outcomes to increase transparency and interpretability.

X: Indicates topic/subtopic relevant to the specified level of planning or reporting stakeholder engagement.

Within this framework, we indicate minimum reporting guidelines for stakeholder-engaged research, incorporating elements reflecting most frequently discussed as best practices and also reviewing previously published reporting guidelines [3,7]. We contrast this with more comprehensive reporting guidelines for research on stakeholder engagement, built upon previously proposed best practices and hypothesized impacts. Of note, both types of research involve attention to the full range of contexts, processes and outcomes during planning and engagement, and those reporting stakeholder-engaged research may wish to review the comprehensive list to determine if additional elements might be relevant to report for their project.

Application of framework for reporting stakeholder engagement

We conducted stakeholder-engaged research to examine the experience of families referred for subspecialty care. The results of this work were published separately [25]. In Box 1, we provide an example of the minimum reporting recommended by our framework for this stakeholder-engaged research. While conducting this stakeholder-engaged research, we also performed research on stakeholder engagement by examining whether our stakeholder engagement achieved specific process and outcome goals. Compared with our stakeholder-engaged research (which examined family experience with subspecialty care), this research on stakeholder engagement had a separate purpose (examining stakeholder engagement processes and outcomes). In the following methods and results sections, we applied the recommendations for comprehensive reporting for this research on stakeholder engagement, such that this reporting can be contrasted with more minimal reporting in Box 1.

Box 1. Example of minimum reporting for stakeholder-engaged research.

Composition/recruitment

Through recommended practices for stakeholder engagement, we assembled a stakeholder advisory group of six individuals, with equal representation of patients/parents and providers/payers/administrators. Stakeholders were identified through networking, and recruited through individual outreach and meetings

Input desired/goals of engagement

The purpose of the stakeholder advisory group was to incorporate a range of experiences in the planning and execution of our study to optimize interpretability and relevance of findings. Stakeholders were consulted specifically on decisions relating to developing the interview guide, recruiting participants, interpreting results and disseminating findings

Frequency/duration

The stakeholder group met in person every 3–6 months throughout the study period, with interval email communication between meetings

Immediate outcomes

The stakeholder group refined the interview guide and informed participant recruitment. During analysis, they reviewed and refined the preliminary codebook derived from the first five interviews as well as the themes, tables and conceptual models derived from analysis of the complete set of interviews. Stakeholders also provided guidance on dissemination and future directions at the conclusion of the study. The stakeholder group provided over 90 specific recommendations, with nearly two-thirds of these recommendations related to methods, and the remainder related to interpretation of results and dissemination of findings

Research on processes & immediate outcomes of stakeholder engagement

To advance our understanding of the impact of stakeholder engagement, our objective was to examine process measures and immediate outcomes.

Context

In the context of an overall research agenda of examining and improving access to pediatric subspecialty care, we planned to engage a team of stakeholders to inform a qualitative examination of family experiences of subspecialty care referrals, and to guide subsequent research efforts. For the qualitative project (the results of which are reported elsewhere [26]), objectives for this team of stakeholders included refining research questions, designing research methods, interview guides and analysis plans, reviewing and interpreting results, planning dissemination and prioritizing future research activities. Informed by best practices of stakeholder engagement [4,5], we sought to incorporate the values, knowledge and experiences of a range of stakeholders, including patients, caregivers, physicians, payers and administrators, which required assembly of a new team of stakeholders. The primary investigator was new to stakeholder engagement, and guided by a senior investigator with significant experience in stakeholder engagement and community-based participatory research. External funding and dedicated time were available for this effort.

Processes

We identified and recruited six individuals to represent identified stakeholder groups and maintain a balance of patient representatives (patients/parents) and system representatives (physicians, payers and administrators). We identified potential stakeholders through personal networks, including recommended contacts from clinical and research colleagues. After identification of these individuals, we began relationship building, first through an individual face-to-face or telephone meeting with the principal investigator (PI). If the potential stakeholder wished to continue relationship building at the conclusion of this meeting, we further explained the stakeholder role and invited the potential stakeholder to join the team.

Once the complete stakeholder team was identified, we sought to further clarify expectations with written materials (including a welcome letter, a summary of the research project and a summary of stakeholder roles and responsibilities). We aimed to develop these written materials in a way that was inclusive of the varied backgrounds of the stakeholders. These materials addressed the crucial value of each individual's experience; the expected frequency and duration of meeting (every 3–4 months for at least 2–3 years); additional methods of communication; and initial and long-term goals. These materials were distributed via email with an invitation to dialog about these materials, and we began the process of scheduling our first group face-to-face meeting at that time as well. Out of respect for stakeholder's competing obligations, we offered the option of telephone or video conference participation at meetings, and also intermittently held smaller meetings or one-on-one meetings to accommodate scheduling conflicts. We offered reimbursement for parking. Additional project-specific materials were distributed prior to the first meeting to allow stakeholders to engage with, form opinions on and ask questions prior to meeting. We identified specific decisions to be made in an agenda which was also precirculated.

At our first meeting, we revisited expectations and invited further dialog on roles and expectations. Through initial introductions, we encouraged each stakeholder to describe their personal experience and expertise after advising each stakeholder to decide about their comfort level sharing any personal or sensitive information. When necessary, we provided brief didactic orientation to specific topics (e.g., general research ethics, the overall research topic and the nature of qualitative research) to promote full participation. We stimulated co-learning by encouraging stakeholders to ask questions and to share their personal experiences and expertise. We addressed decisions preidentified on the agenda as well as any additional concerns or decisions raised by the stakeholders. A research team member was dedicated to recording all comments and recommendations in a log. The PI then reviewed each item of the log after meetings while making appropriate modifications, recorded modifications to improve accountability and provided feedback to the stakeholder team to improve transparency. Feedback was given via email and at subsequent meetings about actions taken in response to stakeholder recommendations as well as the rationale for any recommendations that were not incorporated into the research plan. Recommendations provided by stakeholders between group meetings (through emails or one-on-one meetings) were also entered into this log. After the initial meeting, we continued meetings every 3–6 months through similar processes, with email updates between meetings. During meetings, stakeholders ultimately provided input on research objectives, methods, interview guides, emerging codes in qualitative analysis and the final codebook, preliminary results and tables and the manuscript itself. Stakeholder input was also sought on additional dissemination opportunities and future directions.

Evaluation

We planned our evaluation to examine processes and immediate outcomes. Our primary assessment was through the log of stakeholder recommendations recorded during group meetings and with any interval communication. We also performed a stakeholder survey (Supplementary Appendix) after the first year of stakeholder engagement to further evaluate our stakeholder engagement. Through this evaluation, we aimed to examine process measures (balanced composition, clear roles/expectations, appropriate frequency of engagement, representativeness, co-learning, valuing stakeholder contributions and transparency) and immediate outcomes (impact on methods and interpretation and stakeholder satisfaction). The Institutional Review Board determined that this evaluation of stakeholder engagement was exempt from ethical approval.

Results

Research on stakeholder engagement

Evaluation of processes

Reflecting upon our own stakeholder engagement through the lens of the framework in Table 1, we implemented our planned processes in a way that achieved balanced stakeholder participation, clear roles/expectations, appropriate frequency of engagement, co-learning, transparency and valued stakeholders. Below, we report our evaluation of specific aspects of the stakeholder engagement process.

To evaluate stakeholder recruitment and stakeholder group composition, we assessed recruitment rates and the balance of stakeholders in the group. All potential stakeholders who were invited to participate agreed to join the stakeholder team. We achieved a balanced composition of our stakeholder group, with three patient representatives (two parents and one 18-year-old patient) and three system representatives (one payer, one physician and one administrator).

To evaluate stakeholders’ understanding of their roles, stakeholders were asked to describe their role in an open ended question on the stakeholder survey. Most used the word ‘advisor,’ with some also describing themselves as ‘contributor’ and another elaborating “my role is to add the parent component to the discussion” (parent/patient stakeholder). Stakeholders also were asked to describe their experience compared with their expectations. Many commented that they did not have clear expectations at the start of their participation, with additional comments including “I wasn't sure what to expect. I agreed to participate because I felt that I could be an asset by contributing my expertise and knowledge…” (provider/system stakeholder) and “Having never experienced this role before, I would say I did not know what to expect. I expected to learn, and have. I expected to contribute, and I have” (parent/patient stakeholder).

To assess frequency of engagement, we determined the number of recommendations from stakeholders at meetings and via emails, and assessed stakeholder satisfaction with frequency of contact. Three face-to-face meetings were held during the first year, with meetings scheduled to allow for maximal stakeholder attendance. One-to-two participants joined each meeting via teleconference. Multiple email updates were sent by the PI throughout the first year. Face-to-face meetings yielded the majority of stakeholder recommendations (Table 2). In our stakeholder survey, respondents liked the frequency of in-person meetings and email updates, although one respondent expressed interest in more interval email updates.

Table 2. . Source, mode, topic and outcome of recommendations made by stakeholders in our stakeholder experience.

| Stakeholder recommendation characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Stakeholder making recommendation: | |

| – Parent | 32 (35) |

| – Patient | 8 (9) |

| – Payer | 12 (13) |

| – Provider | 23 (25) |

| – Administrator | 8 (9) |

| – Multiple members/group |

8 (9) |

| Mode of communication: | |

| 11 (12) | |

| – Meetings |

80 (88) |

| Aspect of research informed: | |

| – Methods | |

| Interview guide | 36 (40) |

| Other (sampling, recruitment): | 23 (25) |

| – Results/interpretation | 16 (18) |

| – Dissemination | 4 (4) |

| – Future directions/hypotheses |

12 (13) |

| Incorporated into research: | |

| – Yes | 70 (77) |

| – No | 5 (5) |

| – Future recommendation | 16 (18) |

To assess representativeness of engagement across different types of stakeholders, we examined the volume of recommendations made by each stakeholder. All participants provided multiple concrete recommendations to modify the study (Table 2), with balanced representation of stakeholder voices: 44% of recommendations came from patient representatives, while 47% came from system representatives.

To assess co-learning, we asked stakeholders if they felt they received adequate information to participate comfortably, and if they felt they contributed as much as they desired. In our stakeholder survey, respondents agreed that they had received all of the information they wanted to receive, and that they had been able to share all of the comments and advice that they wished to share.

To evaluate our success at valuing stakeholder contributions, we examined stakeholder attendance at meetings, as a measure of whether they felt their time and contributions were valued. Meeting times were identified after requesting availability from all stakeholders. Stakeholder attendance at scheduled meetings was high, with accommodations such as multiple meetings and video conferences made to allow greater engagement. Ultimately, only one stakeholder was unable to attend one scheduled meeting time after alternative options were explored.

To evaluate transparency, we asked stakeholders in our survey whether the research team had adequately responded to their feedback. In our stakeholder survey, all respondents reported that the research team had responded adequately to their feedback/recommendations. Part of this response, we believe, was due to our practice of emailing stakeholders after meetings with a summary of the modifications made to the research based on their recommendations. The impact of this transparency was noted in additional comments on the stakeholder survey: “I feel like my contributions have been validated and deemed useful during our meetings” (provider/system stakeholder) and “You do a really great job at encouraging input, more importantly, you use it” (parent/patient stakeholder).

Evaluation of immediate outcomes

Stakeholders provided 91 concrete recommendations to improve the research project during the first year (Table 2). Nearly two-thirds of stakeholder recommendations related to changes in project methods. Of these, 60% were recommendations to refine the interview guide to improve clarity of questions, relevance of findings or interpretability of results. Additional recommendations regarding methods included specific guidance that informed sampling and recruitment. Of all recommendations, 18% informed result interpretation, 4% addressed translation and dissemination at the conclusion of analysis and 13% were future directions or follow-on hypotheses. Altogether, 77% of recommendations were incorporated into the research plan and 5% were unable to be incorporated. The remaining 18% related to dissemination activities or future research activities that are pending or ongoing.

At the conclusion of the first study guided by this stakeholder group, the stakeholders continue to be engaged and ready to inform additional activities. In our stakeholder survey, respondents reported overall satisfaction, stating “I am just grateful that I am bringing the parents voice to the discussions. I think that is so important” (parent/patient stakeholder) and “My experience has been rewarding” (provider/system stakeholder).

Evaluation of intermediate outcome

While we did not specifically inquire about intermediate outcomes, one stakeholder addressed empowerment through participation: “I have also been excited to be invited to other events as a result of working on this project” (patient/provider stakeholder). Regarding efficiency of research efforts, the first manuscript [26] was published 11 months after the final interview was completed. We did not collect data regarding the impact of our stakeholder engagement process on additional intermediate outcomes.

Evaluation of long-term outcomes

Our evaluation did not assess the impact of stakeholder engagement on long-term outcomes.

Framework refinement

As we refined our framework and used it to guide reporting of our experience, we found a need to separately address key values, principles or meta-criteria underpinning the stakeholder engagement process outside of the main framework. These values, which broadly aim to address power differentials among stakeholder groups, include respect, trust, legitimacy, competence, fairness and accountability [2,6,9,16,22]. These values are believed to be important for stakeholder engagement, but are difficult to study directly, perhaps in part because they do not translate directly into specific actionable steps, measurable processes or objective outcomes. For this reason, we propose an exploratory grid suggesting processes onto which these values map (Table 3), allowing the primary framework to focus on more readily reportable topics. Our goal in providing this grid is to suggest that these values can and should inform decisions about stakeholder engagement processes, and that detailed reporting of specific processes may help communicate if and how values were reflected in the research.

Table 3. . Alignment of stakeholder engagement processes and underlying values for stakeholder engagement.

| Process | Respect | Trust | Legitimacy | Fairness | Competence | Accountability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recruitment of stakeholders |

|

|

X |

X |

|

|

| Stakeholder composition |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

| Setting of expectations |

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

| Methods of decision making |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

| Frequency and duration of engagement |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

|

| Representativeness |

|

|

X |

|

|

|

| Co-learning |

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

| Valuing stakeholder contributions |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

|

| Transparency | X | X | X | X |

X: Indicates the specified value may be reflected in the specified stakeholder engagement process.

Discussion

We propose a framework to assist with planning, evaluating and reporting stakeholder engagement. Recognizing that research using stakeholder-engaged processes includes studies while engaging stakeholders (stakeholder-engaged research) and studies about engaging stakeholders (research on stakeholder engagement), we suggest distinct reporting guidelines for both types of work. We then applied this framework to provide two structured reports of our stakeholder engagement in the context of a qualitative study. We describe our experience engaging stakeholders to illustrate the difference between minimal reporting for stakeholder-engaged research (as shown in Box 1) and comprehensive reporting for research on stakeholder engagement (as provided in the Methods and the Results). Recognizing that stakeholder engagement takes many forms and that best practices are still being established, we do not seek to present our stakeholder engagement experience as a standard, but rather to use our experience to demonstrate how application of our reporting framework can provide greater rigor, transparency and consistency in reporting both stakeholder-engaged research and research on stakeholder engagement.

Standardized rubrics have allowed improved transparency and quality of other methodologies [27], and have the potential to improve the quality of stakeholder engagement research as well, which may in turn improve our ability to understand stakeholder engagement best practices. Specifically, more standardized reporting may help clarify the value of specific stakeholder engagement processes, ideally allowing identification of the approaches to stakeholder engagement that are most effective in achieving desired goals. Prior authors have suggested that a more nuanced approach to stakeholder engagement may be needed to “match the right type of stakeholder to the right time” [14] – more detailed literature, such as advocated in this framework, is needed to guide this.

In proposing minimum reporting for stakeholder-engaged research, we aimed to identify the fewest elements needed to allow readers and reviewers to understand the role of stakeholders in stakeholder-engaged research, without creating an undue burden on investigators. Specifically, we acknowledge that space limitations in manuscripts limit the detail that can be conveyed when stakeholder engagement is not the focus of study, and also that delaying publication to collect intermediate and long-term outcomes would be counterproductive for a method that hopes to improve research efficiency and translation. Our framework recommends a similar level of reporting for stakeholder-engaged research as the seven-item questionnaire proposed by Concannon et al. [3]. One difference is that the seventh item of that questionnaire asks about the impact of engagement on intermediate outcomes such as relevance and uptake, which may not be measured or available at the time of publication of stakeholder-engaged research. Additionally, by pairing this minimal reporting with more comprehensive reporting in our framework, we highlight the range of topics not required by minimum reporting guidelines, but still relevant for planning and potentially relevant for reporting individual studies.

In proposing comprehensive reporting for research on stakeholder engagement, we outline a broader range of concepts, processes and outcomes synthesized from prior work. To investigate the relationships between these concepts will require more in-depth research on stakeholder engagement. Assessment of process measures and immediate outcomes through research on stakeholder engagement, such as we report here, will offer initial guidance on what has been effective for individual teams. Elevating the level of reporting in both stakeholder-engaged research and research on stakeholder engagement will allow systematic reviews to yield greater insight and nuance into best practices, at least for process measures and immediate outcomes. Building the evidence regarding intermediate and long-term outcomes may require alternative approaches. For some topics (i.e., efficiency of research, empowerment of stakeholders and sustainability of partnerships), research on stakeholder engagement may involve collecting data from investigators and stakeholders through surveys, interviews and focus groups. For other topics (i.e., value of evidence, uptake of evidence and improved clinical/healthy policy decision making), research on stakeholder engagement may involve assessment of these parameters by relevant groups (i.e., clinicians, patients and policy makers) or objective measures of translation into clinical practice. While there may be significant hurdles to studying some of these concepts, we hope that organizing relevant contexts, processes and outcomes in our framework will clarify targets for future work.

In separating values that underlie stakeholder engagement from contexts, processes and outcomes, we aimed to separate actionable, objective concepts from core principles, in hopes that this might offer clearer guidance for those planning, evaluating and reporting on stakeholder engagement. For example, Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute's Patient and Family Engagement Rubric [4] discusses transparency, honesty and trust. Transparent sharing of information is a process one can actively embark upon, while trust is a more complex principle with limited data on how to achieve it [27]. The goal of attaining trust may shape how one approaches decisions about other processes such as setting of expectations and methods of decision making, but one must engage in multiple complex processes to achieve trust, and one cannot easily measure whether it has been attained. For this reason, we offer a grid proposing related processes and values in Table 3 to demonstrate how specific processes offer opportunities to reflect specific values. The framework and grid, while exploratory, may be helpful starting points for those in the planning stages of stakeholder engagement, allowing greater intentionality in planning by considering the values imparted by their process decisions. Measuring the attainment of these values through specific processes and the impact of these values on specific outcomes would add to our understanding of stakeholder engagement, but such measurement may be complicated.

Regarding our actual stakeholder engagement experience, our evaluation suggests that attention to contexts, processes and underlying values in planning our stakeholder engagement resulted in representative stakeholder participation, clear roles/expectations, active and reciprocal engagement, transparency and stakeholder satisfaction. Our stakeholder engagement resulted in modification of study methods, interpretation, dissemination and future directions. Stakeholders described satisfaction and empowerment, but our study was not designed for further evaluation of intermediate or long-term outcomes. Combined with additional reports of equal or greater detail, our experience may allow for identification of specific contexts and processes that are most influential in shaping successful experiences, allowing the development of a more nuanced approach to stakeholder engagement as advocated previously [14], by matching the right engagement approach and the right stakeholders to the right task.

Our framework was developed from synthesis of prior literature and our own experience, allowing us to generate a list of contexts, processes and outcomes for reporting of stakeholder engagement that sought to be inclusive. However, much of the literature used to develop this framework was theoretical rather than evidence based, such that our framework should be viewed as exploratory and will need to be adapted as the field advances. Prior models and recommendations were identified through a targeted literature review rather than systematic review, and may not have captured all relevant studies. In particular, the inconsistency in terminology that we discussed above may have hindered finding additional potentially relevant articles. We did not engage stakeholders in our framework development (although it was informed by our experience engaging stakeholders). Future work refining this framework may benefit from multiple stakeholder perspectives. Regarding our evaluation of stakeholder engagement, we did not design our evaluation to examine intermediate or long-term outcomes. Further work, ideally guided by clear conceptual frameworks, will be needed to understand the impact of stakeholder engagement on long-term outcomes such as improved patient health, patient decision making and clinicians/policy-makers decision making. However, we believe our proposed framework provides a clearer lens for recognizing gaps in the literature when planning evaluation work, and will foster clearer reporting of contexts, methods and outcomes to advance methods in stakeholder engagement.

Conclusion

Improved evidence is needed to understand the impact of stakeholder engagement on research, and guidelines are needed to improve this evidence. We propose a framework for planning, evaluating and reporting stakeholder engagement to improve the quality of both stakeholder-engaged research and research on stakeholder engagement. Using this framework, we describe our evaluation of stakeholder engagement processes and immediate outcomes in the context of a qualitative study to demonstrate the detailed reporting generated through application of our framework.

Future perspective

We anticipate that as the need for standardization of stakeholder-engaged research and research on stakeholder engagement is recognized, consistent reporting guidelines will be adopted in the coming years. This will, in turn, generate greater rigor and transparency in stakeholder engagement, improving the quality of evidence in the field. High-quality evidence will allow the development of evidence-based best practice guidelines for stakeholder engagement, including attention to which engagement processes work best for specific populations and purposes. By promoting increased transparency and detail in planning and reporting stakeholder engagement, the proposed framework aims to begin this process of improving reporting, improving evidence and strengthening research in stakeholder engagement.

Executive summary.

Background

Stakeholder engagement in research aims to improve research quality through incorporation of multiple perspectives.

The impact of stakeholder engagement is not well documented, and advancing the field is hindered by lack of comprehensive framework for planning, studying and reporting stakeholder engagement.

We aimed to develop a framework to guide planning, evaluating and reporting both stakeholder-engaged research (research informed by stakeholders) and research on stakeholder engagement (research about stakeholder engagement).

Methods

We synthesized conceptual models and frameworks regarding stakeholder engagement, and applied and refined this framework through reporting planned methods and observed results of our stakeholder engagement experience.

Results

The developed framework identifies contexts, processes and outcomes to facilitate planning, studying and reporting both stakeholder-engaged research and research on stakeholder engagement.

Specific values of stakeholder engagement were identified that should guide decisions about specific processes of stakeholder engagement.

Our stakeholder experience suggests that our planned contexts and processes resulted in desired process measures (including representative stakeholder participation, clear roles/expectations, active and reciprocal engagement and transparency) and impacted immediate outcomes (including modification of study methods, interpretation, dissemination and future directions).

Conclusion

The developed framework of comprehensive contexts, processes and outcomes aims to improve rigor and transparency in planning, studying and reporting stakeholder engagement.

By standardizing reporting of stakeholder engagement, we hope to improve the quality of evidence in the field, allowing heightened understanding of the outcomes of stakeholder engagement and the best methods to achieve those outcomes.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

Supported in part by grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K12HS022989, KN Ray), the National Institutes of Health (K24HD075862, E Miller) and the Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh of the UPMC Health System (KN Ray). The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: •• of considerable interest

- 1.Concannon TW, Meissner P, Grunbaum JA, et al. A new taxonomy for stakeholder engagement in patient-centered outcomes research. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2012;27(8):985–991. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2037-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esmail L, Moore E, Rein A. Evaluating patient and stakeholder engagement in research: moving from theory to practice. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 2015;4(2):133–145. doi: 10.2217/cer.14.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Summarizes hypothesized impacts of stakeholder engagement and current evidence for these impacts.

- 3.Concannon TW, Fuster M, Saunders T, et al. A systematic review of stakeholder engagement in comparative effectiveness and patient-centered outcomes research. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2014;29(12):1692–1701. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2878-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Reviews prior literature and proposes a seven-item stakeholder engagement questionnaire.

- 4.PCORI. PCORI Engagement Rubric. 2014. www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/Engagement-Rubric.pdf

- 5.Hoffman A, Montgomery R, Aubry W, Tunis SR. How best to engage patients, doctors, and other stakeholders in designing comparative effectiveness studies. Health Aff. (Millwood) 2010;29(10):1834–1841. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lavallee DC, Williams CJ, Tambor ES, Deverka PA. Stakeholder engagement in comparative effectiveness research: how will we measure success? J. Comp. Eff. Res. 2012;1(5):397–407. doi: 10.2217/cer.12.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Discusses meta-criteria for stakeholder engagement in comparative effectiveness research.

- 7.Guise JM, O'Haire C, McPheeters M, et al. A practice-based tool for engaging stakeholders in future research: a synthesis of current practices. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2013;66(6):666–674. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Provides a detailed review and checklist of best practices for stakeholder-engaged prioritization of research topics.

- 8.O'Haire C, McPheeters M, Nakamoto E, et al. Methods Future Research Needs Reports. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; MD, USA: 2011. Engaging stakeholders to identify and prioritize future research needs. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deverka PA, Lavallee DC, Desai PJ, et al. Stakeholder participation in comparative effectiveness research: defining a framework for effective engagement. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 2012;1(2):181–194. doi: 10.2217/cer.12.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Provides a conceptual mode for inputs, methods and outputs of stakeholder engagement in comparative effectiveness research.

- 10.Jagosh J, Macaulay AC, Pluye P, et al. Uncovering the benefits of participatory research: implications of a realist review for health research and practice. Milbank Q. 2012;90(2):311–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00665.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mullins CD, Abdulhalim AM, Lavallee DC. Continuous patient engagement in comparative effectiveness research. JAMA. 2012;307(15):1587–1588. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burke JG, Jones J, Yonas M, et al. PCOR, CER, and CBPR: alphabet soup or complementary fields of health research? Clin. Transl. Sci. 2013;6(6):493–496. doi: 10.1111/cts.12064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brett J, Staniszewska S, Mockford C, et al. Mapping the impact of patient and public involvement on health and social care research: a systematic review. Health Expect. 2014;17(5):637–650. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2012.00795.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cottrell E, Whitlock E, Kato E, et al. Research White Papers. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; MD, USA: 2014. Defining the benefits of stakeholder engagement in systematic reviews. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Camden C, Shikako-Thomas K, Nguyen T, et al. Engaging stakeholders in rehabilitation research: a scoping review of strategies used in partnerships and evaluation of impacts. Disabil. Rehabil. 2015;37(15):1390–1400. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2014.963705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frank L, Forsythe L, Ellis L, et al. Conceptual and practical foundations of patient engagement in research at the patient-centered outcomes research institute. Qual. Life Res. 2015;24(5):1033–1041. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0893-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pandi-Perumal SR, Akhter S, Zizi F, et al. Project stakeholder management in the clinical research environment: how to do it right. Front. Psychiatry. 2015;6:71. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shippee ND, Domecq Garces JP, Prutsky Lopez GJ, et al. Patient and service user engagement in research: a systematic review and synthesized framework. Health Expect. 2015;18(5):1151–1166. doi: 10.1111/hex.12090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cukor D, Cohen LM, Cope EL, et al. Patient and other stakeholder engagement in patient-centered outcomes research institute funded studies of patients with kidney diseases. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016;11(9):1703–1712. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09780915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forsythe LP, Ellis LE, Edmundson L, et al. Patient and stakeholder engagement in the PCORI pilot projects: description and lessons learned. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2016;31(1):13–21. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3450-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mackie TI, Sheldrick RC, De Ferranti SD, Saunders T, Rojas EG, Leslie LK. Stakeholders’ perspectives on stakeholder-engaged research (SER): strategies to operationalize patient-centered outcomes research principles for SER. Med. Care. 2016;55(1):19–30. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saunders T, Mackie TI, Shah S, Gooding H, De Ferranti SD, Leslie LK. Young adult and parent stakeholder perspectives on participation in patient-centered comparative effectiveness research. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 2016;5(5):487–497. doi: 10.2217/cer-2016-0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woolf SH, Zimmerman E, Haley A, Krist AH. Authentic engagement of patients and communities can transform research, practice, and policy. Health Aff. (Millwood) 2016;35(4):590–594. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Effective Health Care Program. Learning modules: engaging stakeholders in the Effective Health Care Program. 2016. http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/index.cfm/tools-and-resources/how-to-get-involved-in-the-effective-health-care-program/learning-modules-engaging-stakeholders-in-the-effective-health-care-program/

- 25.Ray KN, Ashcraft LE, Kahn JM, Mehrotra A, Miller E. Family perspectives on high-quality paediatric subspeciality referrals. Acad. Paediatr. 2016;16(6):594–600. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.05.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Equator Network Enhancing the quality and transparency of health research. www.equator-network.org

- 27.Frerichs L, Kim M, Dave G, et al. Stakeholder perspectives on creating and maintaining trust in community-academic research partnerships. Health Educ. Behav. 2016;44(1):182–191. doi: 10.1177/1090198116648291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]