Abstract

To explore the mechanisms by which NO elicits endothelial cell (EC) migration we used murine and bovine aortic ECs in an in vitro wound-healing model. We found that exogenous or endogenous NO stimulated EC migration. Moreover, migration was significantly delayed in ECs derived from endothelial NO synthase-deficient mice compared with WT murine aortic EC. To assess the contribution of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-13 to NO-mediated EC migration, we used RNA interference to silence MMP-13 expression in ECs. Migration was delayed in cells in which MMP-13 was silenced. In untreated cells MMP-13 was localized to caveolae, forming a complex with caveolin-1. Stimulation with NO disrupted this complex and significantly increased extracellular MMP-13 abundance, leading to collagen breakdown. Our findings show that MMP-13 is an important effector of NO-activated endothelial migration.

Keywords: angiogenesis, endothelium, vasular remodeling

Wound healing is an orchestrated cascade of enzymatic activities that converge toward damage repair. Wound healing involves inflammation and angiogenesis and is tightly regulated by cytokines (1). Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a critical cytokine involved in angiogenesis, and nitric oxide (NO) is a downstream effector (2, 3). VEGF increases NO levels in endothelial cells (ECs) by activating endothelial NO synthase (eNOS/NOS3) (4–7). Recently, the role of eNOS in EC migration has been demonstrated in vivo and in vitro (8, 9) but the precise mechanism by which NO regulates migration is unknown.

ECs migrate as a result of an injury and during angiogenesis from preexisting vessels. The process is tightly regulated by matrix turnover, in which matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) play a pivotal role (10–12). We have previously reported that NO induces MMP-13 expression and activity in bovine aortic ECs (BAECs) (13, 14).

MMPs are extracellular matrix-degrading endopeptidases. MMP expression and activity can be found in physiological and pathological situations, such as tissue development, atherosclerosis, ovarian function, arthritis, osteoarthritis, cancer, angiogenesis, and wound healing (15). MMP-13 was initially discovered in mammalian cell carcinomas and is also expressed by several cell types, including endothelium (13, 16–18).

Here, we present evidence that MMP-13 is a downstream effector of NO-activated EC movement. We have developed a wound-healing model in BAECs and aortic cells from eNOS WT and eNOS-deficient mice. We show that aortic ECs lacking MMP-13 experience delayed migration, and aortic ECs from eNOS null mice present delayed cell migration and a significant decrease in MMP-13 expression. In addition, we present data showing that MMP-13 exists in association with caveolin-1 in resting cells, and that this complex is disrupted in the presence of NO, leading to the secretion of MMP-13 to the extracellular media. We postulate that NO induces EC movement in part via the disruption of the MMP-13/caveolin-1 complex, which in turn releases the secretion of active MMP-13 to the extracellular matrix.

Methods

Reagents. Cell culture supplies, GFR Matrigel solution, and the BD cell recovery solution (MatriSperse) were from Becton Dickinson. Cell culture transwells were from Costar, calf serum was from BioWhittaker, and cell culture gelatin and antibiotics were from Sigma. Collagen type I was from ICN. Autoradiography film was from Kodak. Poly(vinylidene difluoride) protein transfer membranes were from Millipore, and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, ECL-detecting immunoblot system, and protein A-Sepharose were from Amersham Pharmacia. EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture tablets were from Roche Molecular Biochemicals. OptiMEM and Lipofectamine were from GIBCO/BRL. MMP-13 polyclonal antibodies and Fluorsave coverslip mounting solution were from Calbiochem. MMP-13 mAbs were from Chemicon. Anti-MT1–MMP was from Oncogene Science. Anti-caveolin-1 was from Becton Dickinson. The Silencer small interfering RNA (siRNA) construction kit was from Ambion (Cambridgeshire, U.K.).

Animals. WT C57BL/6 mice and (C57BL/6,129) eNOS null mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and housed in our own animal facilities in isolated rooms.

Cells. BAECs were incubated in gelatin or collagen type I as described (14).

Murine aortic ECs (MAECs) were cultured from aortas extracted from anesthetized animals after death. The aortas were sectioned into 2-mm pieces, deposited in Matrigel solution, and fed with fresh growth medium for 7 days [DMEM/HAM's medium (19), 20% FBS, 0.05 mg/ml penicillin/streptomycin, and 2.5 μg/ml amphotericin]. The tissue was removed, and 500 μl of BD Cell recovery solution was added to each culture. The Matrigel layer was removed and poured on ice for 1 h. The solution was centrifuged at 4°C, resuspended in 4 ml of growing medium, and plated.

MAECs were selected by their ability to express the intercellular adhesion molecule-2 (ICAM-2) protein and purified with a flow cytometry cell sorter (DAKO). Purification was verified by confocal microscopy of MAECs double-stained with von Willebrand factor antibodies.

Wound-Healing Assay. BAECs or MAECs were grown in six-well plates, and a straight incision was made on the monolayer. Cell movement was monitored over a time course by microscopy and calculated by determining the area unoccupied by cells at every time point, allowing us to establish the rate of cell movement between individual time points [image software for Macintosh, by Wayne Rasband (20), National Institutes of Health, Bethesda].

Immunoblot Analysis. Cell lysate extraction and protein immunoblots were performed as described (13).

Immunoprecipitation. Cells were disrupted with RIPA buffer (1 × PBS/1% Nonidet P-40/0.5% sodium deoxycholate/0.1% SDS), low-salt lysis buffer, or octyl-glucoside buffer and precleared with the appropriate control IgG with protein A-Sepharose. Precleared supernatants were incubated for 16 h with the corresponding antibodies with protein A-Sepharose and washed four times with cold PBS. Samples were boiled and analyzed by SDS/PAGE.

Preparation of Caveolin-Enriched Low-Density Membrane Fractions. BAECs were grown in T150 flasks and resuspended in 2 ml of Mes-buffered saline (25 mM Mes, pH 6.5/0.15 M NaCl/EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture tablet/0.5% Triton X-100). Cells were homogenized by passing through a 0.45 × 16-mm syringe at 4°C. The homogenate was adjusted with 2 ml of 80% sucrose in Mes-buffered saline. The solution was separated by ultracentrifugation in a discontinuous sucrose gradient (40%-30%–5%) in a SW40 rotor (Beckman) at 200,000 × g for 18 h. After centrifugation, 1-ml fractions were collected, starting at the upper part of the centrifuge tube. To each fraction, 1 ml of cold acetone was added and the mixture was precipitated overnight at 4°C. Samples were centrifuged, pellets were dried, and 100 μl of RIPA buffer was added to each sample.

Confocal Microscopy. BAECs were grown on cover slides, and after treatment, washed twice with PBS. Cells were fixed and permeabilized or not with cold methanol and incubated with 3% BSA in PBS for 1 h. Covers were incubated with primary antibodes for 1 h, washed four times with PBS, incubated with fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibodies, and visualized by confocal microscopy (Radiance 2100, Bio-Rad). The fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibodies Alexa J43 (excitation wavelength, 543 nm; emission wave length, 586–590 nm), swine anti-goat-FITC (excitation wavelength, 488 nm; emission wave length, 515 nm), and rabbit anti-mouse-FITC were used. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst (excitation wave length, 405 nm; emission wave length, 424 nm).

Immunohistochemistry. Aortas from 6-week-old mice were harvested, and aortic rings were perfused with 0.9% NaCl and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. Tissues were frozen, and serial sections were cut with a sledge cryostate (CM1900, Leica, Deerfield, IL). Free-floating sections were washed in PBS and incubated in PBS containing 3% hydrogen peroxide for 30 min to quench the endogenous peroxidase. Sections were incubated in 0.2% Triton X-100 and 3% normal serum for 1 h and then incubated with an anti-MMP-13. After washing with PBS, sections were incubated with a biotinylated secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories), and then with peroxidase-linked ABC (Vector Laboratories). Peroxidase activity was shown by nickel enhancement 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride.

Gene Silencing. MMP-13 expression was silenced in BAECs with the Silencer siRNA construction kit from Ambion, according to the manufacturer's guidelines. In brief, we synthesized sets of two self-complementary 29-oligonucleotide templates, in which the first eight nucleotides at the 3′ end contain the T7 primer domain at which the T7 RNA polymerase uses the leader sequence 5′-CCTGTCTC-3′. The remaining 21 nucleotides were homologous with specific regions of the bovine MMP-13 mRNA. Sequences were subject to blast, and finally the following set of oligonucleotides were selected: MMP-13 sense 5′-AAAGGAAGCATAAAGTGGCTTCCTGTCTC-3′; MMP-13 antisense 5′-AAAAGCCACTTTATGCTTCCTCCTGTCTC-3. Expression of MMP-13 in BAECs was silenced by transfecting the dsRNA with the Lipofectamine method (Invitrogen) as described (13). We transfected cells with different concentrations of dsRNA, and MMP-13 was monitored 16 and 72 h after transfection.

Metalloproteinase Activity. MMP-13, MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-7, and MMP-9 activities were measured by using a fluorescent substrate from Chemicon as described (13).

Statistical Analysis. Unless otherwise specified, data are expressed as means ± SD, and experiments were performed at least three times in duplicate. Comparisons were made with ANOVA followed by Dunnett's modification of the t test, whenever comparisons were made with a common control or by nonparametric tests as appropriate. Error bars represent ± SD.

MMP-13 and Caveolin-1 Expression. Full-length MMP-13 cDNA was cloned into pQE30 expression vector (Qiagen, Valencia, Ca) fused to a 6XHis tail at the end terminus (pHis-MMP-13). Expression was induced in Escherichia coli cultures with 1 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside for 3 h at 37°C. Recombinant MMP-13 was purified by Ni2+-affinity chromatography (HisTrap kit, Amersham Pharmacia), according to the manufacturer's instructions, and monitored by immunoblot with anti-6XHis (Sigma) and anti-MMP-13 (Chemicon) antibodies.

Recombinant caveolin-1 was inserted into the pGEX2 vector (Amersham Pharmacia). GST–caveolin-1 was used to routinely transform BL21 DE3 competent cells (Novagen), and the recombinant protein was purified by using a glutathione agarose resin (Amersham Pharmacia) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Results

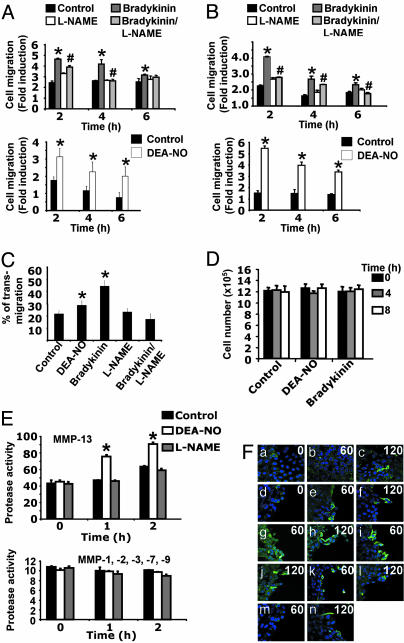

NO Induces EC Migration. We performed wound-healing assays in BAECs (Fig. 1A) and MAECs (Fig. 1B) incubated with the NO donor 2-(N,N-diethylamino)-diazenolate-2-oxide diethylammonium salt (DEA-NO) (100 μM), and endogenous NO production was stimulated by the incubation with bradykinin (10-6 M). NO stimulated the migration of the endothelium during the first 2 h of incubation when compared with wounded but nonchallenged cell cultures. The specific role of NO was evaluated by incubating with the NO synthase inhibitor l-nitroarginine methyl ester (l-NAME) (500 μM). In cells stimulated with bradykinin plus l-NAME the contribution of NO was significantly reduced (Fig. 1 A and B Upper). The same experiments were performed by plating BAECs on collagen type I, with similar results (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

NO induces EC movement in a wound-healing model. (A and B) BAEC (A) or MAEC (B) monolayers were injured and treated with 10-6 M bradykinin, 500 μM l-NAME, bradykinin/l-NAME, or 100 μM DEA-NO, and cell movement was monitored by microscopy (n = 3 by triplicate; mean ± SD; *, P < 0.05 vs. control; #, P < 0.05 vs. bradykinin). (C) BAEC monolayers were seeded on 8-μm porous transwell filters and treated with 100 μM DEA-NO, 10-6 M bradykinin, 0.5 mM l-NAME, or the combination bradykinin/l-NAME. After 6 h of plating, transmigration was evaluated by confocal microscopy (see Methods for details, n = 2 by triplicate; *, P < 0.05 vs. control). (D) ECs were injured and treated with 100 μM DEA-NO or 10-6 M bradykinin. Total cell number was evaluated at the indicated times (n = 3 by triplicate; mean ± SD). (E) EC monolayers were treated with 100 μM DEA-NO or 500 μM l-NAME. MMP activities were measured by fluorimetry from culture supernatants collected at regular time points (n = 3 by quadruplicate; mean ± SD; *, P < 0.05 vs. control). (F) EC monolayers (a–c) were injured (d–n, see Methods for details) and treated with 100 μM DEA-NO (b, c, g, and h), 100 μM DEA (m and n), 10-6 M bradykinin (i and j), or 10-6 M bradykinin/500 μM l-NAME (k and l). MMP-13 was visualized over time (0, 1, and 2 has indicated) with immunohistochemical staining (MMP-13, FITC, green; nuclei Hoechst, blue) by confocal microscopy (magnification: ×40, n = 3).

ECs were also tested for their capacity to migrate in transwell plates (see Methods for details). In cells treated either with DEA-NO (100 μM) or bradykinin (10-6 M) transmigration was significantly increased with respect to control cells and bradykinin-stimulated cells treated with l-NAME (500 μM) (Fig. 1C).

To exclude a proliferative effect of NO, ECs were treated with the same stimuli as above, and then counted at regular intervals. No significant differences in cell number were shown (Fig. 1D).

Among the different enzymes, MMPs play a pivotal role in cell migration, and we found that in supernatants collected during the first 2 h of treatment, MMP-13 activity was induced in response to NO, whereas no significant differences were detected for MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-3, MMP-7, and MMP-9 (Fig. 1E). In view of this result, we decided to examine the distribution of MMP-13 by confocal microscopy during a time course of wound healing. We found that when aortic ECs were stimulated with DEA-NO or bradykinin migration was faster and MMP-13 was accumulated at the wound edge, when compared with DEA (without the NO moiety) stimulation (Fig. 1F g and h vs. m and n). The effect partially depended on NO, because l-NAME caused a delay in the cell migration and MMP-13 accumulation (Fig. 1F i and j vs. k and l). These results suggest MMP-13 acts as a downstream effector in the NO-mediated EC migration.

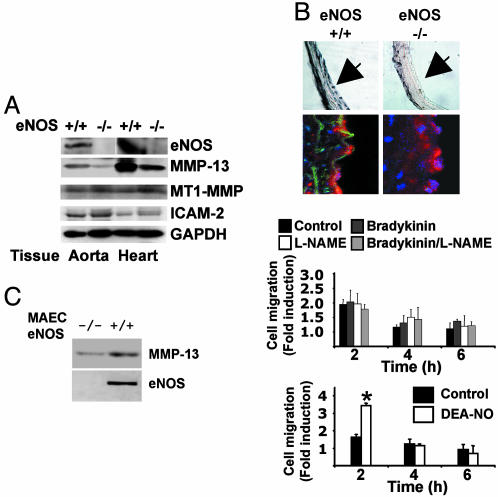

NO Synthase Null Mouse ECs Migrate Slower Than NO Synthase WT ECs in a Wound-Healing Model. To elucidate whether MMP-13 may serve as an NO-effector molecule during cell migration, we found that MMP-13 expression was reduced in eNOS-null mouse hearts and aortas, as detected by immunoblot (Fig. 2A). Immunohistochemical analysis of aortic rings from eNOS-deficient mice also revealed a decreased MMP-13 expression in the endothelial layer (Fig. 2B Upper), whereas the levels of the endothelial marker ICAM-2 remained the same (Fig. 2B Lower). In addition, during wound-healing assays in MAECs from eNOS-deficient mice, we found that a single addition of NO was not as effective as in MAECs from eNOS WT mice (Fig. 2C vs. Fig. 1B). Moreover, no differences were observed in cell migration in response to bradykinin, consistent with the lack of eNOS in these cells (Fig. 2C Upper), as compared with their WT counterparts (Fig. 1B), in which the bradykinin effect depended on NO, because l-NAME inhibited the stimulatory effect on cell migration (Fig. 1B). Thus, lack of eNOS inhibits MMP-13 expression and NO-mediated cell migration.

Fig. 2.

ECs from eNOS-deficient mice migrate slower and show lower MMP-13 levels when compared with their eNOS WT counterparts. (A) Aortas and hearts from a pool of eNOS-deficient mice and eNOS WT mice were homogenized and used to evaluate eNOS, MMP-13, MT1-MMP, ICAM-2, and GAPDH expression (n = 3 animals by triplicate). (B) Aortic rings were isolated from eNOS-deficient mice and eNOS WT mice, and MMP-13 was visualized by immunohistochemistry and immunohistofluorescence using an anti-MMP-13 antibody. MMP-13 was visualized by peroxidase staining (Upper, magnification ×20) and FITC (Lower, magnification ×60). Aortic nuclei were stained with Hoechst. ICAM-2 expression was visualized in red (n = 5). (C) MAECs from eNOS WT or eNOS-deficient mice were isolated, and lysates were immunobloted to detect the expression of MMP-13 and eNOS (Left). In addition, a wound-healing assay was performed in cells treated with 100 μM DEA-NO, 10-6 M bradykinin, 500 μM l-NAME, and bradykinin/l-NAME (n = 3 by triplicate; mean ± SD; *, P < 0.01 vs. control).

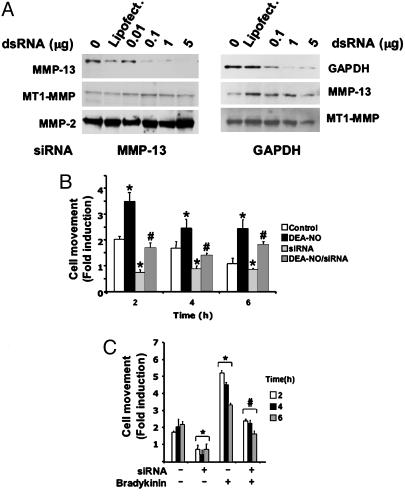

MMP-13 Is an Active Component of NO-Mediated EC Migration. To test the contribution of NO during migration of cells in which MMP-13 is down-regulated, we performed a wound-healing assay in BAECs in which MMP-13 was silenced by RNA interference. We collected protein lysates from BAECs transiently transfected with different amounts of MMP-13 dsRNAs, tracked MMP-13 expression by immunoblot, and selected the optimum RNA dose (0.1 μg, 50 nM, Fig. 3A Left). As a control, the expression of MT1-MMP and MMP-2 was evaluated (Fig. 3A Left) and GAPDH expression was silenced, monitoring the expression of MMP-13 and MT1-MMP (Fig. 3A Right). Cells in which MMP-13 was reduced migrated slower than did control cells, DEA-NO-stimulated cells (Fig. 3B), and bradykinin-stimulated ECs (Fig. 3C). Neither DEA-NO nor bradykinin was able to counteract the inhibited cell migration in MMP-13-silenced cells. These results demonstrate the contribution of MMP-13 as an effector of NO-dependent cell migration.

Fig. 3.

EC migration depends on MMP-13 expression. (A) Immunoblot detection of MMP-13, MT1-MMP, and MMP-2 (Left) and GAPDH, MMP-13, and MT1-MMP (Right) in MMP-13 (Left) and GAPDH (Right) silenced cells. Shown is one representative experiment from a total of three. (B) ECs were injured and treated with 100 μM DEA-NO (n = 3 by quadruplicate; mean ± SD; *, P < 0.05 vs. control; #, P < 0.05 vs. DEA-NO). (C) ECs were subject or not to MMP-13 silencing, injured, and treated with 10-6 M bradykinin (n = 3 by triplicate; mean ± SD; *, P < 0.05 vs. nonstimulated/nonsilenced; #, P < 0.05 vs. stimulated with bradykinin/nonsilenced).

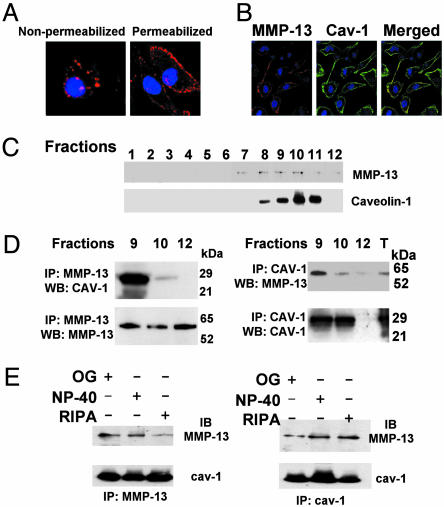

MMP-13 Is Associated with Caveolin-1 in EC Membranes. To explore the mechanism exerted by NO on MMP-13-mediated cell migration, we first investigated the location of MMP-13 in aortic ECs. We found by confocal microscopy that in nonpermeabilized cells MMP-13 is clustered in the membrane of BAECs, whereas in permeabilized BAECs a small portion of MMP-13 is also detected inside the cells (Fig. 4A) and colocalizes with caveolin-1 (Fig. 4B). By isolating caveolin-1-enriched fractions (see Methods for details) we found that MMP-13 was present both in caveolin-1-positive and -negative fractions (Fig. 4C). Crossed coimmunoprecipitation experiments revealed that MMP-13 is complexed with caveolin-1 in caveolar-enriched fractions (Fig. 4C, fractions 9 and 10), as well as in total cell extracts, whereas it does not form a complex in the noncaveolar fraction 12 (Fig. 4D). To exclude the possibility of lipid-mediated interaction, we performed immunoprecipitation assays incubated with a buffer containing octyl-glucoside, a detergent that removes any trace of protein–lipid interaction, and the caveolin-1–MMP-13 complex was not disrupted, confirming that no lipid association is involved in the complex (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

MMP-13 colocalizes with caveolin-1 in endothelial plasma membranes. (A) Confocal microscopy analysis of BAECs showing the expression of MMP-13 in nonpermeabilized and permeabilized BAECs. (B) Confocal microscopy analysis showing the expression of caveolin-1 (green) and MMP-13 (red) in BAECs. Merged panel shows colocalization of MMP-13 and caveolin-1 (yellow) (n = 5). (C) Caveolae-enriched fractions were isolated and identified by immunoblot with anti-caveolin-1. MMP-13 was also evaluated in the same fractions (n = 3). (D) Caveolin-1-positive (fractions 9 and 10) and -negative (fraction 12) fractions from ECs were subjected to cross-coimmunoprecipitation with anti-MMP-13 (Left) and anti-caveolin-1 (Right). Caveolin-1 or MMP-13 were detected by immunoblot (n = 4). (E) Cell lysates were subjected to cross-coimmunoprecipitation as indicated, in octyl-glucoside (OG), Nonidet P-40, and RIPA buffers (n = 3).

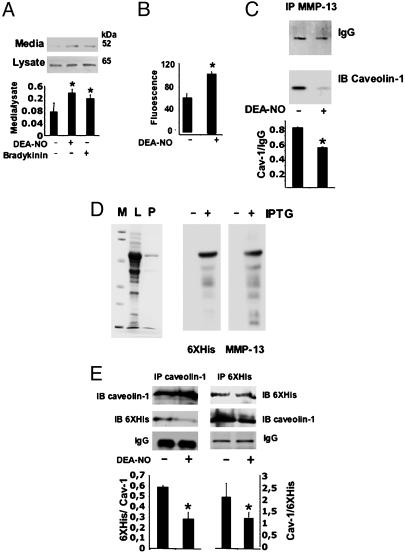

NO Promotes the Dissociation of MMP-13 from Caveolin-1 and Induces the Release of MMP-13 into the Extracellular Matrix. The fact that NO induces the release and activity of MMP-13 to the extracellular matrix was addressed by immunobloting MMP-13, collected from cultured media in cells treated either with DEA-NO or bradykinin, as detected by Western blot (Fig. 5A), as well as the collagenolytic activity measured in media collected under these conditions (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

NO disrupts the MMP-13/caveolin-1 complex in BAEC. (A) Immunoblot of MMP-13 from cell lysates or culture media collected after 2 h of treatment of ECs with 100 μM DEA-NO or 10-6 M bradykinin. The graph represents the densitometric analysis of data from three independent experiments (mean ± SD; *, P < 0.05). (B) MMP-13 activity assay in cell media from ECs treated for 2 h with 100 μM DEA-NO (n = 3; mean ± SD; P < 0.05). (C) Immunoprecipitation of MMP-13 from caveolin-1-enriched fractions of vehicle and ECs treated with 100 μM DEA-NO. Caveolin-1 was detected by immunoblot (n = 4 by triplicate; mean ± SD; *, P < 0.01). (D) MMP-13 was expressed in E. coli and purified by affinity chromatography. IP, immunoprecipitation; WB, Western blot. (Left) Coomassie staining of a 12% SDS/PAGE. M, molecular weight marker; L, bacterial lysate from cells treated with 1 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG); P, purified MMP-13. (Right) Immunoblots from purified MMP-13, with anti-6XHis and anti-MMP-13 antibodies. (E) Crossed-coimmunoprecipitation experiments from purified MMP-13 incubated with cell lysates of BAECs for 16 h at 4°C and treated with DEA-NO or vehicle for 2 h (n = 3; mean ± SD; *, P < 0.05).

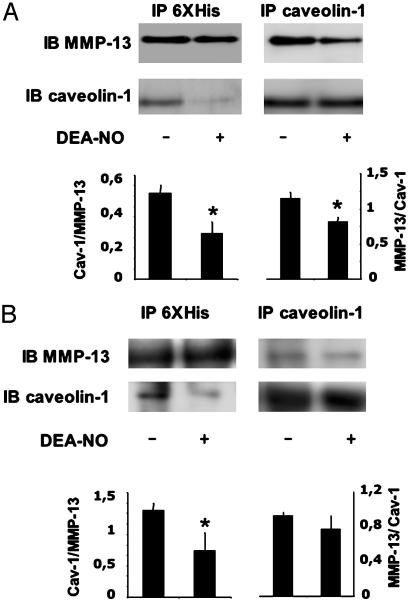

To explore whether NO disrupted the association with caveolin-1, EC extracts were enriched in MMP-13 by immunoprecipitation. In NO-treated ECs, the association of caveolin-1–MMP-13 was significantly reduced (Fig. 5C). To further confirm this effect, we expressed and purified recombinant MMP-13 fused to a 6XHis tag at the N terminus (Fig. 5D). Recombinant MMP-13 was incubated with cell lysates from BAECs treated with vehicle or 100 μM DEA-NO, in which caveolin-1 or 6XHis proteins were immunoprecipitated (Fig. 5E). A 60-kDa 6XHis protein was decreased in extracts treated with DEA-NO in caveolin-1-enriched extracts (Fig. 5E Left). In a similar fashion in 6XHis-enriched cell extracts we found similar levels of MMP-13 in vehicle and NO-treated cells, whereas caveolin-1 was increased in those extracts treated with vehicle (Fig. 5E Right) compared with those treated with NO. In addition, we demonstrated this effect by expressing recombinant caveolin-1 fused to a GST tag (Fig. 6A). The incubation of E. coli-expressed recombinant 6XHis–MMP-13 and GST–caveolin-1 proteins in the absence and presence of DEA-NO showed the same effect. The complex detected by immunoprecipitation with the corresponding anti-MMP-13 or anticaveolin-1 antibodies was reduced in the presence of DEA-NO (Fig. 6A). To elucidate whether exposure of NO affects the interaction by targeting MMP-13 and/or caveolin-1 we first preincubated 6XHis–MMP-13 or GST–caveolin-1 with 100 μM DEA-NO, and after incubation with the corresponding DEA-NO-untreated protein (GST–caveolin-1 or 6XHis–MMP-13, respectively) the same immunoprecipitation analysis was performed as before (Fig. 6B). Whereas DEA-NO-treated GST–caveolin-1 did not affect the binding to 6XHis–MMP-13, when 6XHis–MMP-13 was preincubated with DEA-NO, a significant reduction in the binding to GST–caveolin-1 was detected. These data support the notion that NO targets MMP-13 and disrupts it from the complex with caveolin-1.

Fig. 6.

NO disrupts the in vitro MMP-13/caveolin-1 complex. (A) Recombinant 6XHis–MMP-13 and GST–caveolin-1 were purified and subject to immunoprecipitation (IP) experiments in the presence or absence of 100 μM DEA-NO to visualize the binding to caveolin-1 and MMP-13, respectively (n = 3; mean ± SD; *, P < 0.05). IB, immunoblot. (B) Recombinant 6XHis–MMP-13 or GST–caveolin-1 were pretreated with 100 μM DEA-NO for 1 h, bound to GST–caveolin or 6XHis–MMP-13, respectively (nontreated with DEA-NO), and subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) experiments (n = 3; mean ± SD; *, P < 0.05). IB, immunoblot.

Discussion

Our data demonstrate the importance of MMP-13 in EC migration activated by NO. MMP-13 is located at the plasma membrane of the injured EC monolayers, but NO stimulates MMP-13 release and EC migration.

Previous reports have described the contribution of MMP-13 to wound repair in several tissues, including bone, cornea, and joint tissue (21, 22). However, the significance of MMP-13 in EC migration was still unknown. The finding that NO promotes MMP-13 expression in BAECs (13) encouraged us to investigate its possible role in vascular ECs. We evaluated the importance of MMP-13 in EC migration by silencing its expression. We have demonstrated that MMP-13 is essential for ECs to migrate across the plate and that the promigratory effect of NO partially depends on MMP-13.

Other investigators have shown that NO is part of the downstream signaling cascade mediated by vascular endothelial growth factor during EC migration (4–8, 23–26), and the NO-mediated cGMP signaling pathway has recently been implicated in this process (27). However, to our knowledge the precise interplay with the extracellular matrix has not been studied before. Our experiments identify a pathway involving the extracellular matrix by which NO regulates migration. Immunohistochemical analysis of MMP-13 in aortic rings from eNOS WT mice and eNOS-deficient mice shows a reduction in MMP-13 levels when eNOS is absent, a result that is consistent with our previous findings in BAEC (13). By isolating ECs from eNOS-deficient mice we have been able to show that EC migration and MMP-13 expression are both inhibited as compared with WT mouse ECs. Furthermore, exogenous addition of NO to eNOS-null mouse ECs restored the behavior exhibited by their counterpart WT cells at early time points. These data led us to propose that MMP-13 is an important downstream effector of NO during EC migration.

The fact that other metalloproteinases are located within the caveolar region (28, 29) prompted us to investigate whether MMP-13 could also be located there. The association of caveolin-1 in complexes with other proteins frequently is linked to enzymatic inhibition, as occurs with eNOS. Even when eNOS and MMP-13 are sharing caveolin-1 as a partner in the membrane, we found that MMP-13 and eNOS do not interact directly in ECs (data not shown). Our data are consistent with a model in which NO disrupts the interaction of MMP-13 and caveolin-1, promoting its secretion (Fig. 5). This effect results in increased EC migration, and eventually in ECM degradation and angiogenesis. However, other pathophysiological processes may also be targets for this molecular interplay. NO has been considered as a double-edged sword. NO production is beneficial during several processes, including cell migration (30–32), but also may have other deleterious consequences, especially when produced at high concentrations, as has been reported in aneurysm rupture and atherosclerosis (33, 34). NO generated at micromolar amounts arising from macrophages or smooth muscle cells, provoking extensive MMP-13 secretion, may contribute to the tissue remodeling associated with these conditions.

The effect of NO in dissociating caveolin-1 scaffold has been reported (35). Based on previous results from our laboratory (14) and studies of the roles of reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen intermediate in the activation of other MMPs (36–38), perhaps NO could directly activate MMP-13 by promoting its catalytic activation by cleavage of the pro-peptide. Activation by S-nitrosylation of the cysteine switch by NO and/or related species is a plausible alternative and has been recently reported for MMP-9 (39).

The results we have presented here provide evidence for a central role for MMP-13 in the migration of ECs and the contribution of NO to the activation of this metalloproteinase. This study may help to increase understanding of the pluripotential roles of NO in vascular physiology and pathophysiology.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Juan Miguel Redondo, Alicia García-Arroyo, and Carlos López-Otín for helpful discussion and suggestions during the elaboration of the present manuscript and Elvira Arza for valuable assistance with confocal microscopy and MAEC cultures. This work was supported by Plan Nacional de I+D+I Salud y Farmacia Grant 2002-00399, Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología “Programa Ramón y Cajal,” Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid Grant 08.4/0023/2003 1 (to C.Z.), European Union Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional Grant 2FD97-1432 and Plan Nacional de I+D+I Salud y Farmacia Grant 2000-0149 and Salud y Farmacia Grant 2003-01039) (to S.L.), and a grant-in-aid from the Spanish Society of Nephrology 2001 and Red Temática Cooperativa de Enfermedades Cardiovasculares C03/01 from the Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo (to C.Z. and S.L.).

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: EC, endothelial cell; MAEC, murine aortic EC; BAEC, bovine aortic EC; eNOS, endothelial NO synthase; ICAM-2, intercellular adhesion molecule-2; DEA-NO, 2-(N,N-diethylamino)-diazenolate-2-oxide diethylammonium salt; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase; siRNA, small interfering RNA; l-NAME, l-nitroarginine methyl ester.

References

- 1.Schwentker, A., Vodovotz, Y., Weller, R. & Billiar, T. R. (2002) Nitric Oxide 7, 1-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papapetropoulos, A., Garcia-Cardena, G., Madri, J. A. & Sessa, W. C. (1997) J. Clin. Invest. 100, 3131-3139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ziche, M., Morbidelli, L., Choudhuri, R., Zhang, H. T., Donnini, S., Granger, H. J. & Bicknell, R. (1997) J. Clin. Invest. 99, 2625-2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dimmeler, S., Dernbach, E. & Zeiher, A. M. (2000) FEBS Lett. 477, 258-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Noiri, E., Lee, E., Testa, J., Quigley, J., Colflesh, D., Keese, C. R., Giaever, I. & Goligorsky, M. S. (1998) Am. J. Physiol. 274, C236-C244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Urbich, C., Reissner, A., Chavakis, E., Dernbach, E., Haendeler, J., Fleming, I., Zeiher, A. M., Kaszkin, M. & Dimmeler, S. (2002) FASEB J. 16, 706-708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chavakis, E., Dernbach, E., Hermann, C., Mondorf, U. F., Zeiher, A. M. & Dimmeler, S. (2001) Circulation 103, 2102-2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee, P. C., Salyapongse, A. N., Bragdon, G. A., Shears, L. L., 2nd, Watkins, S. C., Edington, H. D. & Billiar, T. R. (1999) Am. J. Physiol. 277, H1600-H1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murohara, T., Asahara, T., Silver, M., Bauters, C., Masuda, H., Kalka, C., Kearney, M., Chen, D., Symes, J. F., Fishman, M. C., et al. (1998) J. Clin. Invest. 101, 2567-2578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galvez, B. G., Matias-Roman, S., Albar, J. P., Sanchez-Madrid, F. & Arroyo, A. G. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 37491-37500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schaffer, M. R., Tantry, U., Thornton, F. J. & Barbul, A. (1999) Eur. J. Surg. 165, 262-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shukla, A., Rasik, A. M. & Shankar, R. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biochem. 200, 27-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zaragoza, C., Soria, E., Lopez, E., Browning, D., Balbin, M., Lopez-Otin, C. & Lamas, S. (2002) Mol. Pharmacol. 62, 927-935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zaragoza, C., Balbin, M., Lopez-Otin, C. & Lamas, S. (2002) Kidney Int. 61, 804-808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagase, H. & Woessner, J. F., Jr. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 21491-21494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freije, J. M., Diez-Itza, I., Balbin, M., Sanchez, L. M., Blasco, R., Tolivia, J. & Lopez-Otin, C. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 16766-16773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stahle-Backdahl, M., Sandstedt, B., Bruce, K., Lindahl, A., Jimenez, M. G., Vega, J. A. & Lopez-Otin, C. (1997) Lab. Invest. 76, 717-728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balbin, M., Pendas, A. M., Uria, J. A., Jimenez, M. G., Freije, J. P. & Lopez-Otin, C. (1999) Apmis 107, 45-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Becher, H., Grau, A., Steindorf, K., Buggle, F. & Hacke, W. (2000) J. Epidemiol. Biostat. 5, 277-283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fagan, S. C., Payne, L. W. & Houtekier, S. C. (1989) DICP Ann. Pharmacother. 23, 957-962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamagiwa, H., Tokunaga, K., Hayami, T., Hatano, H., Uchida, M., Endo, N. & Takahashi, H. E. (1999) Bone 25, 197-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ye, H. Q., Maeda, M., Yu, F. S. & Azar, D. T. (2000) Invest. Ophthalmol. Visual Sci. 41, 2894-2899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamuro, M., Polan, J., Natarajan, M. & Mohan, S. (2002) Atherosclerosis 162, 277-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goligorsky, M. S., Budzikowski, A. S., Tsukahara, H. & Noiri, E. (1999) Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 26, 269-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noiri, E., Hu, Y., Bahou, W. F., Keese, C. R., Giaever, I. & Goligorsky, M. S. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 1747-1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pearson, J. D. (2000) Lupus 9, 183-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawasaki, K., Smith, R. S., Jr., Hsieh, C. M., Sun, J., Chao, J. & Liao, J. K. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 5726-5737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Annabi, B., Lachambre, M., Bousquet-Gagnon, N., Page, M., Gingras, D. & Beliveau, R. (2001) Biochem. J. 353, 547-553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Puyraimond, A., Fridman, R., Lemesle, M., Arbeille, B. & Menashi, S. (2001) Exp. Cell Res. 262, 28-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aicher, A., Heeschen, C., Mildner-Rihm, C., Urbich, C., Ihling, C., Technau-Ihling, K., Zeiher, A. M. & Dimmeler, S. (2003) Nat. Med. 9, 1370-1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Babaei, S. & Stewart, D. J. (2002) Cardiovasc. Res. 55, 190-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poppa, V., Miyashiro, J. K., Corson, M. A. & Berk, B. C. (1998) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 18, 1312-1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Napoli, C. & Ignarro, L. J. (2001) Nitric Oxide 5, 88-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fukuda, S., Hashimoto, N., Naritomi, H., Nagata, I., Nozaki, K., Kondo, S., Kurino, M. & Kikuchi, H. (2000) Circulation 101, 2532-2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li, H., Brodsky, S., Basco, M., Romanov, V., De Angelis, D. A. & Goligorsky, M. S. (2001) Circ. Res. 88, 229-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wenk, J., Brenneisen, P., Wlaschek, M., Poswig, A., Briviba, K., Oberley, T. D. & Scharffetter-Kochanek, K. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 25869-25876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rajagopalan, S., Meng, X. P., Ramasamy, S., Harrison, D. G. & Galis, Z. S. (1996) J. Clin. Invest. 98, 2572-2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang, H. J., Zhao, W., Venkataraman, S., Robbins, M. E., Buettner, G. R., Kregel, K. C. & Oberley, L. W. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 20919-20926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gu, Z., Kaul, M., Yan, B., Kridel, S. J., Cui, J., Strongin, A., Smith, J. W., Liddington, R. C. & Lipton, S. A. (2002) Science 297, 1186-1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]