Abstract

Background

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common clinically significant arrhythmia in adults and a major risk factor for ischemic stroke. Nonetheless, previous research suggests that many individuals diagnosed with AF lack awareness about their diagnosis and inadequate health literacy may be an important contributing factor to this finding.

Methods and Results

We examined the association between health literacy and awareness of an AF diagnosis in a large, ethnically diverse cohort of Kaiser Permanente Northern and Southern California adults diagnosed with AF between January 1, 2006 and June 30, 2009. Using self‐reported questionnaire data completed between May 1, 2010 and September 30, 2010, awareness of an AF diagnosis was evaluated using the question “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you have a heart rhythm problem called atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter?” and health literacy was assessed using a validated 3‐item instrument examining problems because of reading, understanding, and filling out medical forms. Of the 12 517 patients diagnosed with AF, 14.5% were not aware of their AF diagnosis and 20.4% had inadequate health literacy. Patients with inadequate health literacy were less likely to be aware of their AF diagnosis compared with patients with adequate health literacy (prevalence ratio=0.96; 95% CI [0.94, 0.98]), adjusting for sociodemographics, health behaviors, and clinical characteristics.

Conclusions

Lower health literacy is independently associated with less awareness of AF diagnosis. Strategies designed to increase patient awareness of AF and its complications are warranted among individuals with limited health literacy.

Keywords: arrhythmia, atrial fibrillation, awareness, health literacy

Subject Categories: Arrhythmias, Catheter Ablation and Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator, Health Services

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common clinically significant arrhythmia in adults.1, 2 Individuals with AF suffer from an increased risk of morbidity and mortality stemming from events such as ischemic stroke, heart failure, and sudden cardiac death.3 In 2010, it was estimated that 5.2 million people in the United States were living with their AF and a projected 12.1 million people were expected to have AF by the year 2030.4 However, prior research has shown that many individuals who are diagnosed with AF may lack awareness of their disease.5, 6, 7 These individuals may also not fully understand the risks and benefits associated with the use of anticoagulants, one of the main approaches used to mitigate AF‐associated thromboembolism.8, 9, 10, 11, 12

Lack of awareness of an AF diagnosis, coupled with a limited understanding of both the risks and benefits associated with provider‐prescribed AF treatments, may lead to treatment nonadherence. Three primary factors have been reported to be associated with patient nonadherence to anticoagulation medication, including patient's perception and knowledge about its purpose, their understanding of both the risks and benefits associated with the use of anticoagulants, and their socioeconomic status.13 Despite these factors, few interventions have been implemented to increase awareness and/or knowledge of AF as a means of improving AF treatment adherence. Results from the interventions that have been conducted found very marginal improvements in both patient awareness and knowledge of AF.14

Health literacy, “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions,”15 may be one factor contributing to the limited effectiveness of such patient‐focused educational interventions. It has been shown that individuals with limited health literacy are at an increased risk for disease‐related mortality, have worse disease management, engage less in participatory decision‐making during healthcare visits, and are less adherent to provider‐prescribed medication(s).16, 17, 18, 19, 20 Although it may be intuitive that low health literacy would be associated with lower awareness of an AF diagnosis, it is unclear as to whether or not health literacy is an important driving force behind the lower awareness. Other mechanisms, such as insufficient patient–provider communication, may also contribute to the lack of awareness of an AF diagnosis. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the contribution of health literacy to this relationship by examining the association between health literacy and awareness of an AF diagnosis among individuals who were newly diagnosed with AF.

Methods

Setting

The source population included members of Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) and Southern California (KPSC), 2 integrated healthcare delivery systems that provide comprehensive care to over 8 million individuals throughout the state of California. Membership within KPNC and KPSC is sociodemographically diverse and highly representative of the statewide population.21, 22, 23 Patients are enrolled in these 2 health‐delivery systems through their employer, family member, individually, or a state or federally funded program. All individual‐level data, including sociodemographic information and details of medical care obtained from outpatient, emergency department, and hospital encounters, are captured within a comprehensive electronic health record (EHR) based on the EpicCare system (Epic Systems, Verona, WI).

Study Population

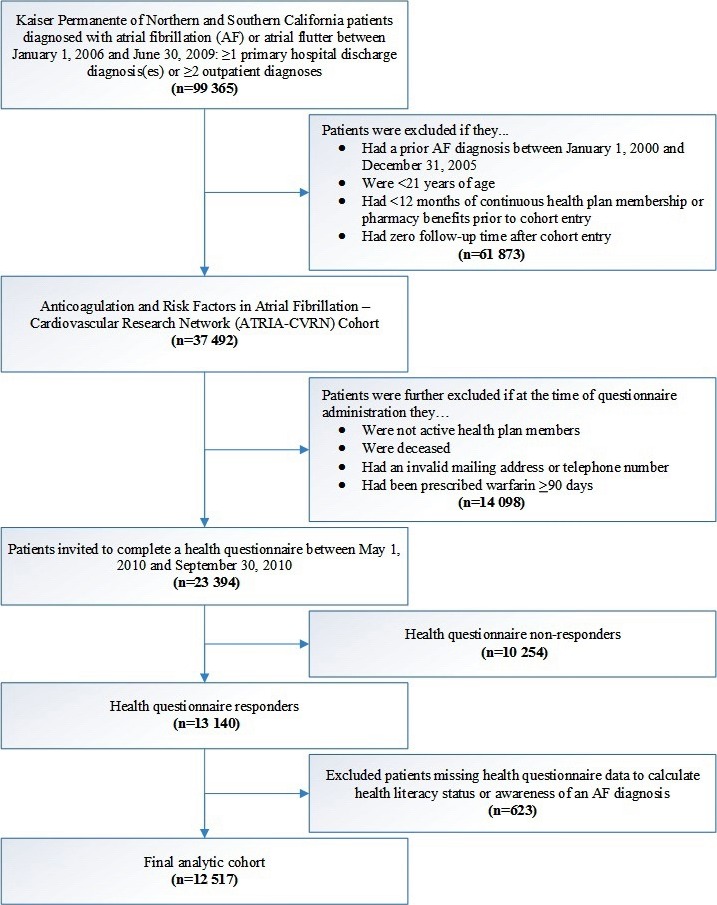

The present investigation included individuals from the source population who were part of the Anticoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation–Cardiovascular Research Network (ATRIA‐CVRN) cohort.24 This cohort included KPNC and KPSC patients who were diagnosed with incident AF or atrial flutter between January 1, 2006 and June 30, 2009 (Figure). An incident AF or atrial flutter diagnosis was defined as having either ≥1 primary hospital discharge diagnosis of AF (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD‐9‐CM] code 427.31) or atrial flutter (ICD‐9‐CM code 427.32) and/or ≥2 outpatient, non–emergency department encounters for AF or atrial flutter with an electrocardiographic physician‐confirmed diagnosis of AF or atrial flutter. Patients were excluded from the ATRIA‐CVRN cohort if they had a prior AF diagnosis between January 1, 2001 and December 31, 2005, were <21 years of age, had <12 months of continuous health plan membership or pharmacy benefits prior to cohort entry, or had no follow‐up time after cohort entry.

Figure 1.

Assembly of the final analytic cohort of patients with complete health questionnaire data to assess health literacy and awareness of an atrial fibrillation diagnosis (n=12 517).

Of 37 492 patients in the ATRIA‐CVRN cohort, 23 394 were invited to complete a 35‐item health questionnaire because they were alive at the time of questionnaire administration (May 1, 2010 and September 30, 2010), were active health plan members, had a valid mailing address or telephone number, and had not been prescribed warfarin ≥90 days before questionnaire administration (to focus only on presumed incident cases of AF). The questionnaire solicited information about personal and family medical history, self‐rated health, personal health behaviors, sociodemographic characteristics, anthropometrics, and overall health literacy. Complete questionnaires were obtained from 13 140 (56.2%) patients, with 9677 (73.6%) completing the questionnaire by mail and 3463 (26.4%) by telephone with a professional interviewer. Mailed questionnaires were available in 3 languages (English, Spanish, and Mandarin) and telephone questionnaires were conducted in either English or Spanish. The median length of time (interquartile range) between being diagnosed with AF or atrial flutter and questionnaire completion was 2.65 years (1.0 years). Patients who were missing data to assess their health literacy (n=471), awareness of an AF diagnosis (n=122), or both (n=30) were excluded. The final analytic cohort for this study included 12 517 patients.

This study was approved by the institutional review boards at KPNC and KPSC. A waiver of written informed consent was obtained because of the nature of the study being a minimal‐risk health questionnaire.

Health Literacy

Health literacy was assessed using 3 questions from the health questionnaire.25, 26, 27, 28 These questions included (1) “How often has someone (like a family member, friend, hospital clinic worker, or caregiver) helped you read hospital or other medical materials?” with the response options of “None of the time,” “A little of the time,” “Some of the time,” “Most of the time,” and “All of the time”; (2) “How often do you have problems learning about your medical condition because of difficulty understanding written information?” with the same response options as the first question; and (3) “How confident are you filling out forms by yourself?” with the response options of “Extremely,” “Quite a bit,” “Somewhat,” “A little bit,” and “Not at all.” For each of these questions, response options were scored from 0 to 4, with higher scores representing lower health literacy. Therefore, the response options “None of the time” and “Extremely” were given a score of 0 and “All of the time” and “Not at all” were given a score of 4. The scores from each of these 3 questions were summed (range 0–12) and the summed score was dichotomized into “adequate health literacy” score 0 to 2 and “inadequate health literacy” score ≥3 (Table 1). This method of dichotomization has been previously identified to optimally distinguish between inadequate and adequate health literacy.25, 26, 27, 28 This 3‐item instrument has also been previously validated among patients from a VA preoperative clinic using the Short Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (S‐TOHFLA). The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was calculated to compare overall performance resulting in values of 0.87 (95% CI=0.78–0.96), 0.76 (95% CI=0.62–0.90), and 0.80 (95% CI=0.67–0.93), respectively, for each question.25

Table 1.

Responses to Health Literacy Questions in 12 517 AF Patients

| Question | n (%) |

|---|---|

| “How often has someone (like a family member, friend, hospital clinic worker, or caregiver) helped you read hospital or other medical materials?” | |

| None of the time=0 | 9740 (77.8) |

| A little of the time=1 | 940 (7.5) |

| Some of the time=2 | 801 (6.4) |

| Most of the time=3 | 404 (3.2) |

| All of the time=4 | 632 (5.1) |

| “How often do you have problems learning about your medical condition because of difficulty understanding written information?” | |

| None of the time=0 | 9971 (79.7) |

| A little of the time=1 | 1172 (9.4) |

| Some of the time=2 | 799 (6.4) |

| Most of the time=3 | 228 (1.8) |

| All of the time=4 | 347 (2.8) |

| “How confident are you filling out forms by yourself?” | |

| Extremely=0 | 8614 (68.8) |

| Quite a bit=1 | 2118 (16.9) |

| Somewhat=2 | 792 (6.3) |

| A little bit=3 | 353 (2.8) |

| Not at all=4 | 640 (5.1) |

| Health literacy | |

| Adequate | 9963 (79.6) |

| Inadequatea | 2554 (20.4) |

Inadequate health literacy was defined as a summed score ≥3.

Awareness of Atrial Fibrillation

Awareness of an AF diagnosis was assessed using the question, “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you have a heart rhythm problem called atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter? Atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter cause an irregular heartbeat.” with the response options of “Yes” and “No.”

Participant Characteristics

Age was determined from the EHR (in years) at the time of AF diagnosis. Sex (male or female) and race/ethnicity (non‐Hispanic white, non‐Hispanic black, non‐Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander, or Hispanic) were also determined from the EHR. Marital status (married/partner or not married/partner), educational attainment (<high school, high school graduate, some college, or Bachelor's degree or higher), household income (≤$25 000, $25 001–$50 000, $50 001–$80 000, or ≥$80 001), physical activity in the past month (based on frequency, duration, and intensity of the activity(ies) categorized into level 0=never, level 1=low/moderate, or level 2=high), cigarette use in the past year (current, former, or never), alcohol use in the past year (current, former, or never), prescribed medication adherence (range: all of the time to less than half of the time), self‐reported health status for poor physical health in the past month (range: 0 to ≥29 days), poor mental health in the past month (range: 0 to ≥29 days), and overall current health (range: poor to excellent) were obtained from the questionnaire.

History of dementia, chronic heart failure, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, ischemic stroke, and transient ischemic attack were collected from the EHR using ICD‐9‐CM codes obtained from both inpatient and outpatient encounters during the 5‐year period prior to questionnaire completion. These diagnoses, excluding dementia, were used to calculate a CHADS2 stroke risk score.29 A Charlson Comorbidity Index score was also calculated using ICD‐9‐CM codes from both inpatient and outpatient encounters during the 1‐year period prior to questionnaire completion, to adjust for severe chronic conditions and risk of mortality in the analyses.30

Statistical Analyses

Sociodemographic characteristics, health behaviors, self‐reported health status, and medical history were compared across health literacy status using χ2 and Wilcoxon signed‐rank tests, as appropriate. Unadjusted and adjusted prevalence ratios (PRs) and 95% CIs were estimated using log‐binomial regression analyses, assessing the association between health literacy and awareness of an AF diagnosis. Models were adjusted for sociodemographics, health behaviors, self‐reported health status, and medical history. All analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Among 12 517 patients diagnosed with incident AF, who responded to the questionnaire items regarding health literacy and awareness of an AF diagnosis, 2554 (20.4%) were categorized as having inadequate health literacy (Table 2). Patients with inadequate health literacy were older, more likely to be female, and less likely to be non‐Hispanic white or be married/with a partner. These patients also had lower socioeconomic status indicators (more likely to have less than a high school education and an income ≤$25 000) and worse overall health (more likely to engage in no physical activity, be a current smoker, have a Charlson Comorbidity Index score ≥3, a CHADS2 risk score ≥3, have diagnosed dementia and self‐report poor physical and mental health ≥29 days in the past month along with poor current overall health). Patients with inadequate health literacy were also more likely to be unaware of their AF diagnosis.

Table 2.

Characteristics of 12 517 Incident AF Patients by Health Literacy Status (All Comparisons Resulted in P<0.001 Based on χ2 and Wilcoxon Signed‐Rank Tests)

| Health Literacy “Adequate” n=9963 (79.6%) | Health Literacy “Inadequate” n=2554 (20.4%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | ||

| Age, y | ||

| Median | 71.3 | 76.9 |

| 25th to 75th% | 63.1 to 78.5 | 67.9 to 83.8 |

| Age group, y, n (%) | ||

| <65 | 3054 (30.7) | 482 (18.9) |

| 65 to 74 | 3235 (32.5) | 608 (23.8) |

| 75 to 84 | 2815 (28.3) | 927 (36.3) |

| ≥85 | 859 (8.6) | 537 (21.0) |

| Male, n (%) | 5798 (58.2) | 1368 (53.6) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Non‐Hispanic white | 7788 (78.2) | 1520 (59.5) |

| Non‐Hispanic black | 486 (4.9) | 179 (7.0) |

| Non‐Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander | 586 (5.9) | 274 (10.7) |

| Hispanic | 567 (5.7) | 417 (16.3) |

| Other/unknown | 536 (5.4) | 164 (6.4) |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||

| Married/partner | 6696 (67.2) | 1503 (58.9) |

| Not married/partner | 3177 (31.9) | 1026 (40.2) |

| Unknown | 90 (0.9) | 25 (1.0) |

| Educational attainment, n (%) | ||

| Less than High School | 401 (4.0) | 595 (23.3) |

| High School Graduate | 1553 (15.6) | 732 (28.7) |

| Some College | 3791 (38.1) | 726 (28.4) |

| Bachelor's Degree or Higher | 4017 (40.3) | 412 (16.1) |

| Unknown | 201 (2.0) | 89 (3.5) |

| Household income, n (%) | ||

| $25 000 or less | 1183 (11.9) | 703 (27.5) |

| $25 001 to $50 000 | 2127 (21.4) | 572 (22.4) |

| $50 001 to $80 000 | 1886 (18.9) | 282 (11.0) |

| More than $80 000 | 2596 (26.1) | 239 (9.4) |

| Unknown | 2171 (21.8) | 758 (29.7) |

| Questionnaire language, n (%) | ||

| English | 9875 (99.1) | 2310 (90.5) |

| Spanish | 83 (0.8) | 216 (8.5) |

| Mandarin | 5 (0.1) | 28 (1.1) |

| Health behaviors | ||

| Physical activity (past month), n (%) | ||

| Level 0 | 547 (5.5) | 395 (15.5) |

| Level 1 | 6836 (68.6) | 1655 (64.8) |

| Level 2 | 2541 (25.5) | 487 (19.1) |

| Unknown | 39 (0.4) | 17 (0.7) |

| Cigarette use (past year), n (%) | ||

| Never | 4094 (41.1) | 1147 (44.9) |

| Former | 5131 (51.5) | 1166 (45.7) |

| Current | 540 (5.4) | 171 (6.7) |

| Unknown | 198 (2.0) | 70 (2.7) |

| Alcohol use (past year), n (%) | ||

| Never | 1691 (17.0) | 794 (31.1) |

| Former | 1824 (18.3) | 629 (24.6) |

| Current | 6308 (63.3) | 1060 (41.5) |

| Unknown | 140 (1.4) | 71 (2.8) |

| Prescribed medication adherence, n (%) | ||

| Less than half of the time | 76 (0.8) | 16 (0.6) |

| About half of the time | 27 (0.3) | 18 (0.7) |

| Most of the time | 130 (1.3) | 83 (3.3) |

| Nearly all of the time | 1390 (14.0) | 384 (15.0) |

| All of the time | 8062 (80.9) | 2017 (79.0) |

| Unknown | 278 (2.8) | 36 (1.4) |

| Self‐reported health status | ||

| Poor physical health (past month), n (%) | ||

| 0 days | 5813 (58.3) | 1052 (41.2) |

| 1 to 7 days | 1910 (19.2) | 488 (19.1) |

| 8 to 21 days | 682 (6.9) | 227 (8.9) |

| 22 to 28 days | 55 (0.6) | 37 (1.5) |

| ≥29 days | 569 (5.7) | 329 (12.9) |

| Unknown | 934 (9.4) | 421 (16.5) |

| Poor mental health (past month), n (%) | ||

| 0 days | 7119 (71.5) | 1383 (54.2) |

| 1 to 7 days | 1255 (12.6) | 322 (12.6) |

| 8 to 21 days | 468 (4.7) | 204 (8.0) |

| 22 to 28 days | 48 (0.5) | 28 (1.1) |

| ≥29 days | 273 (2.7) | 208 (8.1) |

| Unknown | 800 (8.0) | 409 (16.0) |

| Overall current health, n (%) | ||

| Poor | 393 (3.9) | 313 (12.3) |

| Fair | 1910 (19.2) | 916 (35.9) |

| Good | 4040 (40.6) | 895 (35.0) |

| Very good | 2854 (28.7) | 347 (13.6) |

| Excellent | 688 (6.9) | 57 (2.2) |

| Unknown | 78 (0.8) | 26 (1.0) |

| Medical history | ||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (last year), n (%) | ||

| 0 | 3740 (37.5) | 572 (22.4) |

| 1 | 2116 (21.2) | 437 (17.1) |

| 2 | 1413 (14.2) | 402 (15.7) |

| ≥3 | 2694 (27.0) | 1143 (44.8) |

| CHADS2 Score, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 2005 (20.1) | 246 (9.6) |

| 1 | 3687 (37.0) | 629 (24.6) |

| 2 | 3057 (30.7) | 987 (38.7) |

| ≥3 | 1214 (12.2) | 692 (27.1) |

| Dementia, n (%) | 124 (1.2) | 184 (7.2) |

| Health awareness | ||

| Awareness of an atrial fibrillation diagnosis, n (%) | 8781 (88.1) | 1926 (75.4) |

In the unadjusted model, inadequate health literacy was associated with less awareness of an AF diagnosis compared with adequate health literacy (PR=0.86; 95% CI [0.84, 0.88]; Table 3). After controlling for sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, educational attainment, household income, and questionnaire language), the association was attenuated (PR=0.95; 95% CI [0.94, 0.97]), but remained statistically significant. Controlling only for sex, marital status, household income, or questionnaire language did not change the unadjusted estimates. Controlling only for age, race/ethnicity, or educational attainment (PR=0.87, 95% CI [0.85, 0.89]) also did not significantly change the unadjusted estimates. Evaluating the effect of controlling for 2 sociodemographic characteristics including age and race/ethnicity (PR=0.88, 95% CI [0.86, 0.90]), age and educational attainment (PR=0.88, 95% CI [0.86, 0.90]), or race/ethnicity and educational attainment (PR=0.87, 95% CI [0.85, 0.89]) again did not significantly change the unadjusted estimates. However, controlling for age, race/ethnicity, and educational attainment together did account for most of the sociodemographic attenuation (PR=0.92; 95% CI [0.90, 0.94]), with all of the attenuation accounted for after including additional control for sex (PR=0.95; 95% CI [0.93, 0.97]).

Table 3.

Association of Inadequate Health Literacy With Awareness of an AF Diagnosis

| Inadequate Health Literacy | ||

|---|---|---|

| Prevalence Ratio | 95% CI | |

| Awareness of an atrial fibrillation diagnosisa | ||

| Unadjusted | 0.86 | (0.84, 0.88) |

| Age (continuous) | 0.87 | (0.85, 0.89) |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.87 | (0.85, 0.89) |

| Educational attainment | 0.87 | (0.85, 0.89) |

| Age, race/ethnicity | 0.88 | (0.86, 0.90) |

| Age, educational attainment | 0.88 | (0.86, 0.91) |

| Race/ethnicity, educational attainment | 0.87 | (0.85, 0.89) |

| Age, race/ethnicity, educational attainment | 0.92 | (0.90, 0.94) |

| Age, race/ethnicity, educational attainment, sex | 0.95 | (0.93, 0.97) |

| Sociodemographicsb | 0.95 | (0.94, 0.97) |

| Health behaviorsc | 0.96 | (0.94, 0.98) |

| Self‐reported health statusd | 0.96 | (0.94, 0.98) |

| Medical historye | 0.96 | (0.94, 0.98) |

All P<0.001; variables listed are model adjusted covariates; unadjusted estimates did not change after controlling only for sex, marital status, household income, or questionnaire language as individual covariates.

Adjusted for sociodemographics (age [continuous], sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, educational attainment, household income, questionnaire language).

Adjusted for sociodemographics and health behaviors (physical activity, cigarette use, alcohol use, medication adherence).

Adjusted for sociodemographics, health behaviors, and self‐reported health status (physical health, mental health, and overall health).

Adjusted for sociodemographics, health behaviors, self‐reported health status, and medical history (Charlson comorbidity index, CHADS2 score, and dementia).

Adjustment for health behavior characteristics (physical activity, cigarette use, alcohol use, and medication adherence; PR=0.96; 95% CI [0.94, 0.98]), self‐reported health status (physical health, mental health, and overall health; PR=0.96; 95% CI [0.94, 0.98]) and medical history (Charlson Comorbidity Index, CHADS2 and dementia; PR=0.96; 95% CI [0.94, 0.98]) did not further impact our results. Sensitivity analyses, after removing the individuals with diagnosed dementia (n=308), were performed and the results were unchanged.

Discussion

Among a large, diverse sample of adults with incident AF receiving medical care within integrated healthcare delivery systems, lower health literacy was significantly associated with less awareness of an AF diagnosis, even after controlling for sociodemographics, health behaviors, self‐reported health status, and medical history. This has broad implications for both patients and providers when managing care for patients who are newly diagnosed with AF.

Patients with inadequate health literacy were more than twice as likely to be unaware of their AF diagnosis when compared with patients with adequate health literacy (24.6% versus 11.9%). Being unaware of a medical diagnosis, such as AF, can be problematic as it likely implies a lack of understanding of the health risks that are associated with the diagnosis and potential therapeutic options. Furthermore, there may be an increased risk of complications stemming from the primary diagnosis that could develop into secondary comorbidities and, in turn, lead to an increase in overall risk of morbidity, mortality, and cost of care. Researchers have shown that these scenarios do occur among individuals who are unaware of a medical diagnosis. Some examples include potential deficits in seeking and receiving appropriate long‐term care among adult survivors of childhood cancers,31 being unaware of an HIV diagnosis until the development of AIDS,32 misinterpreting symptoms and making uninformed decisions regarding treatment and follow‐up care among women diagnosed with breast cancer33 and being unable to recite the details of the diagnosis and treatment plan among individuals who were diagnosed with breast or colorectal cancer.34 It has also been shown more broadly in not being able to repeat the diagnosis, treatment plan, common side effects, and prescribed medications among individuals released from a municipal teaching hospital.35

Having inadequate health literacy was also related to poorer health in our incident AF population. More than 20% of the patients had inadequate health literacy and their health profiles (self‐reported health status and diagnosed comorbid conditions) were significantly worse when compared with the health profiles of those with adequate health literacy. The patients in our study with inadequate health literacy were more likely to engage in negative health behaviors (smoking and inadequate physical activity); have self‐reported poorer physical, mental, and overall health statuses; and have a higher number of adverse health conditions when compared with patients with adequate health literacy. Many of the patients with inadequate health literacy were persons of color (non‐Hispanic black, non‐Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander or Hispanic), not married or living with a partner in a marriage‐like relationship, and had lower educational attainment and income. The worsening health profile of patients with inadequate health literacy may be explained, in part, by the older age of the population. However, many of these health conditions, and also the individual health behaviors, are known to begin forming at an early age. In addition, as our bivariate analyses indicate, having inadequate health literacy was associated with many of these adverse health conditions. This highlights another more generalizable problem of how health literacy may impact the deterioration of health, which has also been well documented in the literature.36, 37, 38, 39, 40

Lack of awareness of an AF diagnosis, because of problems with health literacy, warrants additional support for creating more effective health literacy programs and improvement strategies. Through improvements in health literacy, AF patients may be able to better understand their health condition, associated complications, and available effective therapies that could lead to increased therapeutic decision‐making and adherence. Some successful health literacy programs that were created for other health conditions may also be effective among individuals diagnosed with AF. For example, a pilot program was created to address Alzheimer's disease symptom recognition and treatment among minority populations facing a higher disease burden. Results of the pilot program demonstrated that implementing an educational training program that was “engaging, dynamic, age and culturally appropriate” improved disease‐specific health literacy.41 Another example was a program that worked with physicians to increase their ability to effectively communicate cancer risk among a low health literacy population. This program resulted in a new baseline model for creating improved patient–provider communication within the hospital's model of care.42 A third example was a school‐based program to increase student knowledge about mental illness. This program implemented a knowledge‐contact approach that facilitated intergroup contact with persons with mental illness as a means to reduce mental illness stigma. Improvements were seen in both mental health literacy and a reduction in mental illness stigma among the school's student body.43 Lastly, another school‐based educational program taught students about asthma, obesity, accidental injury, drug use, and alcohol use through engagement in activities to develop and practice new skills, review of health information at an appropriate health literacy level, and increased health professional exposure to improve overall and topic‐specific health literacy and knowledge. This program saw improvements in the student body in overall health literacy and with respect to these health topics.44

We acknowledge that the cross‐sectional and observational nature of these data preclude us from assessing time‐dependent factors or inferring a causal relationship between health literacy and lack of AF diagnosis awareness. Additionally, the questionnaire was self‐report, either through a mailed questionnaire or a telephone interview, so our results may be subject to recall bias, social desirability bias, and/or interviewer bias, resulting in an overestimate of the patient's awareness of their AF diagnosis. However, there was no reason to believe that these biases would affect those with adequate versus inadequate health literacy systematically leading to nondifferential misclassification of study participants. Complete questionnaires were also obtained from 56.2% of eligible participants, where people with inadequate health literacy may have been less likely to complete the questionnaire, which would result in lower PRs than observed. Despite these limitations, the large, sociodemographically diverse patient population with validated incident AF allowed us to examine the relation between health literacy and awareness of an AF diagnosis in a representative population of patients with incident AF. Additionally, we captured a comprehensive set of demographic and clinical characteristics through the EHR and patient self‐report, which allowed for the detailed investigation of the association between health literacy and AF diagnosis awareness.

Conclusions

In a population of patients diagnosed with incident AF, health literacy was associated with awareness of an AF diagnosis, even after control for sociodemographics, health behaviors, self‐reported health status, and medical history. Patients with inadequate health literacy were less likely to be aware of their AF diagnosis when compared with patients with adequate health literacy. This has broad implications for both patients and providers when managing care for patients with AF. Creating effective health literacy improvement strategies for patients with limited health literacy may be an effective solution for increasing awareness of AF, its potential complications, and available therapeutic options.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by a research grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (RC2 HL101589) and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of Kaiser Permanente or the NIH.

Disclosures

Dr Go has received research funding from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; National Institute on Aging; and iRhythm Technologies. Dr Singer was supported, in part, by the Eliot B. and Edith C. Shoolman Fund of Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, MA). Dr Reynolds has received research funding from iRhythm Technologies. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. ATRIA‐CVRN Members.

(J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e005128 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.116.005128.)28400367

References

- 1. Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, Chang Y, Henault LE, Selby JV, Singer DE. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the anticoagulation and risk factors in atrial fibrillation (ATRIA) study. JAMA. 2001;285:2370–2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chugh SS, Havmoeller R, Narayanan K, Singh D, Rienstra M, Benjamin EJ, Gillum RF, Kim YH, McAnulty JH Jr, Zheng ZJ, Forouzanfar MH, Naghavi M, Mensah GA, Ezzati M, Murray CJ. Worldwide epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: a Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study. Circulation. 2014;129:837–847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, Das SR, de Ferranti S, Despres JP, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Isasi CR, Jimenez MC, Judd SE, Kissela BM, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Liu S, Mackey RH, Magid DJ, McGuire DK, Mohler ER III, Moy CS, Muntner P, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Nichol G, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Rodriguez CJ, Rosamond W, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Towfighi A, Turan TN, Virani SS, Woo D, Yeh RW, Turner MB; American Heart Association Statistics C, Stroke Statistics S . Heart disease and stroke statistics—2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:e38–e360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Colilla S, Crow A, Petkun W, Singer DE, Simon T, Liu X. Estimates of current and future incidence and prevalence of atrial fibrillation in the U.S. adult population. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112:1142–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lip GY, Kamath S, Jafri M, Mohammed A, Bareford D. Ethnic differences in patient perceptions of atrial fibrillation and anticoagulation therapy: the West Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Project. Stroke. 2002;33:238–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nadar S, Begum N, Kaur B, Sandhu S, Lip GY. Patients' understanding of anticoagulant therapy in a multiethnic population. J R Soc Med. 2003;96:175–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Meschia JF, Merrill P, Soliman EZ, Howard VJ, Barrett KM, Zakai NA, Kleindorfer D, Safford M, Howard G. Racial disparities in awareness and treatment of atrial fibrillation: the reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke (REGARDS) study. Stroke. 2010;41:581–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fuller R, Dudley N, Blacktop J. Avoidance hierarchies and preferences for anticoagulation–semi‐qualitative analysis of older patients' views about stroke prevention and the use of warfarin. Age Ageing. 2004;33:608–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lane DA, Ponsford J, Shelley A, Sirpal A, Lip GY. Patient knowledge and perceptions of atrial fibrillation and anticoagulant therapy: effects of an educational intervention programme. The West Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Project. Int J Cardiol. 2006;110:354–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fang MC, Machtinger EL, Wang F, Schillinger D. Health literacy and anticoagulation‐related outcomes among patients taking warfarin. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:841–846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fang MC, Panguluri P, Machtinger EL, Schillinger D. Language, literacy, and characterization of stroke among patients taking warfarin for stroke prevention: implications for health communication. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;75:403–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Smith MB, Christensen N, Wang S, Strohecker J, Day JD, Weiss JP, Crandall BG, Osborn JS, Anderson JL, Horne BD, Muhlestein JB, Lappe DL, Moss H, Oliver J, Viau K, Bunch TJ. Warfarin knowledge in patients with atrial fibrillation: implications for safety, efficacy, and education strategies. Cardiology. 2010;116:61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pandya EY, Bajorek B. Factors affecting patients' perception on, and adherence to, anticoagulant therapy: anticipating the role of direct oral anticoagulants. Patient. 2017;10:163–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Clarkesmith DE, Pattison HM, Lane DA. Educational and behavioural interventions for anticoagulant therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6:CD008600. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008600.pub2. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD008600.pub2/full. Accessed March 31, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Parker R, Ratzan SC. Health literacy: a second decade of distinction for Americans. J Health Commun. 2010;15(suppl 2):20–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schillinger D, Grumbach K, Piette J, Wang F, Osmond D, Daher C, Palacios J, Sullivan GD, Bindman AB. Association of health literacy with diabetes outcomes. JAMA. 2002;288:475–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kripalani S, Gatti ME, Jacobson TA. Association of age, health literacy, and medication management strategies with cardiovascular medication adherence. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81:177–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fraser SD, Roderick PJ, Casey M, Taal MW, Yuen HM, Nutbeam D. Prevalence and associations of limited health literacy in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28:129–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Aboumatar HJ, Carson KA, Beach MC, Roter DL, Cooper LA. The impact of health literacy on desire for participation in healthcare, medical visit communication, and patient reported outcomes among patients with hypertension. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1469–1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ferguson MO, Long JA, Zhu J, Small DS, Lawson B, Glick HA, Schapira MM. Low health literacy predicts misperceptions of diabetes control in patients with persistently elevated A1C. Diabetes Educ. 2015;41:309–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gordon NP. How does the adult Kaiser Permanente membership in Northern California compare with the larger community. Women. 2006;9:9–240. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Koebnick C, Langer‐Gould AM, Gould MK, Chao CR, Iyer RL, Smith N, Chen W, Jacobsen SJ. Sociodemographic characteristics of members of a large, integrated health care system: comparison with US Census Bureau data. Perm J. 2012;16:37–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Derose SF, Contreras R, Coleman KJ, Koebnick C, Jacobsen SJ. Race and ethnicity data quality and imputation using U.S. Census data in an integrated health system: the Kaiser Permanente Southern California experience. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70:330–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Singer DE, Chang Y, Borowsky LH, Fang MC, Pomernacki NK, Udaltsova N, Reynolds K, Go AS. A new risk scheme to predict ischemic stroke and other thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation: the ATRIA study stroke risk score. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000250 DOI: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med. 2004;36:588–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chew LD, Griffin JM, Partin MR, Noorbaloochi S, Grill JP, Snyder A, Bradley KA, Nugent SM, Baines AD, Vanryn M. Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large VA outpatient population. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:561–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stewart DW, Vidrine JI, Shete S, Spears CA, Cano MA, Fernandez‐Correa V, Wetter DW, McNeill LH. Health literacy, smoking, and health indicators in African American adults. J Health Commun. 2015;20:24–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wallace LS, Rogers ES, Roskos SE, Holiday DB, Weiss BD. Brief report: screening items to identify patients with limited health literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:874–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gage BF, van Walraven C, Pearce L, Hart RG, Koudstaal PJ, Boode BS, Petersen P. Selecting patients with atrial fibrillation for anticoagulation: stroke risk stratification in patients taking aspirin. Circulation. 2004;110:2287–2292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD‐9‐CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kadan‐Lottick NS, Robison LL, Gurney JG, Neglia JP, Yasui Y, Hayashi R, Hudson M, Greenberg M, Mertens AC. Childhood cancer survivors' knowledge about their past diagnosis and treatment: Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA. 2002;287:1832–1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brannstrom J, Akerlund B, Arneborn M, Blaxhult A, Giesecke J. Patients unaware of their HIV infection until AIDS diagnosis in Sweden 1996–2002—a remaining problem in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16:702–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Taioli E, Joseph GR, Robertson L, Eckstein S, Ragin C. Knowledge and prevention practices before breast cancer diagnosis in a cross‐sectional study among survivors: impact on patients' involvement in the decision making process. J Cancer Educ. 2014;29:44–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nissen MJ, Tsai ML, Blaes AH, Swenson KK. Breast and colorectal cancer survivors' knowledge about their diagnosis and treatment. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6:20–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Makaryus AN, Friedman EA. Patients' understanding of their treatment plans and diagnosis at discharge. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:991–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Easton P, Entwistle VA, Williams B. Health in the ‘hidden population’ of people with low literacy. A systematic review of the literature. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rudd RE. Improving Americans' health literacy. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2283–2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Peterson PN, Shetterly SM, Clarke CL, Bekelman DB, Chan PS, Allen LA, Matlock DD, Magid DJ, Masoudi FA. Health literacy and outcomes among patients with heart failure. JAMA. 2011;305:1695–1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sorensen K, Van den Broucke S, Fullam J, Doyle G, Pelikan J, Slonska Z, Brand H; Consortium Health Literacy Project E . Health literacy and public health: a systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Noble JM, Hedmann MG, Williams O. Improving dementia health literacy using the FLOW mnemonic: pilot findings from the Old SCHOOL hip‐hop program. Health Educ Behav. 2015;42:73–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Price‐Haywood EG, Roth KG, Shelby K, Cooper LA. Cancer risk communication with low health literacy patients: a continuing medical education program. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(suppl 2):S126–S129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pinto‐Foltz MD, Logsdon MC, Myers JA. Feasibility, acceptability, and initial efficacy of a knowledge‐contact program to reduce mental illness stigma and improve mental health literacy in adolescents. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:2011–2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Diamond C, Saintonge S, August P, Azrack A. The development of building wellness, a youth health literacy program. J Health Commun. 2011;16(suppl 3):103–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. ATRIA‐CVRN Members.