Abstract

Recently, nuclear distribution element-like (NUDEL) has been implicated to play a role in lissencephaly and schizophrenia through interactions with the lissencephaly gene 1 (Lis1) and disrupted-in-schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) products, respectively. Interestingly, NUDEL is the same protein as endooligopeptidase A (EOPA), a thiol-activated peptidase involved in conversion and inactivation of a number of bioactive peptides. In this study, we have cloned EOPA from the human brain and have confirmed that it is equivalent to NUDEL, leading us to suggest a single name, NUDEL-oligopeptidase. In the brain, the monomeric form of NUDEL-oligopeptidase is responsible for the peptidase activity whose catalytic mechanism is likely to involve a reactive cysteine, because mutation of Cys-273 fully abolished NUDEL-oligopeptidase activity without disrupting the protein's secondary structure. Cys-273 is very close to the DISC1-binding site on NUDEL-oligopeptidase. Intriguingly, DISC1 inhibits NUDEL-oligopeptidase activity in a competitive fashion. We suggest that the activity of NUDEL-oligopeptidase is under tight regulation through protein–protein interactions and that disruption of these interactions, as postulated in a Scottish DISC1 translocation schizophrenia cohort, may lead to aberrant regulation of NUDEL-oligopeptidase, perhaps providing a substrate for the pathology of schizophrenia.

Keywords: endooligopeptidase A, neuropeptide metabolism, cysteine peptidase, neurodevelopmental pathology

NUDEL (nuclear distribution element-like) is a homologue of Aspergillus nudE, a member of a group of genes that has been shown to be important in nuclear migration in the fungus (1, 2). Mammalian forms of NUDEL were recently cloned by their interaction with lissencephaly gene 1 product (Lis1) in the yeast two-hybrid system and are essential for neuronal migration, corticogenesis, and axonal outgrowth (3, 4, 5), and, more recently, were shown to play a critical role in neurofilament (NF) assembly and neuronal morphology (6). A number of groups have shown that NUDEL binds to the product of the schizophrenia risk factor gene disrupted-in-schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) (7, 8, 9). DISC1 has been identified as a risk factor for schizophrenia through study of a Scottish family with a balanced (1;11)(q42.1;q14.3) translocation that results in the disruption of the DISC1 locus and cosegregates with major psychiatric disease (10). The putative schizophrenia mutant form of DISC1 fails to bind NUDEL (7, 9). We have also shown that DISC1 and NUDEL bind in a neurodevelopmentally regulated manner and that they can form a trimolecular complex with Lis1 (7). The function of this complex is currently unknown, although it is predicted to play a role in dynein-mediated motor transport.

Surprisingly, the cDNA and deduced amino acid sequences of NUDEL show that it is the same molecule as endooligopeptidase A (EOPA) (formerly EC 3.4.22.19) (11, 12). In vitro EOPA selectively hydrolyzes unstructured oligopeptides (13), such as bradykinin and neurotensin, and converts a number of naturally occurring opioid peptides derived from proenkephalin, prodynorphin, and proopiomelanocortin into enkephalins (14). Thus, two apparently independent physiological roles are likely to be performed by the same protein. The association of NUDEL to cytosolic proteins, such as Lis1, DISC1, and 14-3-3ε, is essential for normal brain function, including development and neuronal migration (5, 9, 15, 16), whereas the peptidase activity of NUDEL-oligopeptidase (NUDEL or EOPA) suggests a role in the regulation of neuropeptide action in the CNS. We have cloned human EOPA, demonstrating that it is the same protein as human NUDEL, which has led us to suggest the single name NUDEL-oligopeptidase. In the rat brain, monomeric NUDEL-oligopeptidase represents the active enzyme, whereas multimerized forms lack enzyme activity. Human NUDEL-oligopeptidase is inhibited by thiol-reactive compounds (17), and the residue Cys-273 is essential for enzymatic activity, which suggests that NUDEL-oligopeptidase belongs to the family of cysteine peptidases. The close proximity of the catalytic Cys-273 residue to the DISC1-binding site centered around residues 266/267 (7, 9) suggests that DISC1 binding could affect the peptide hydrolysis. Indeed, DISC1 is able to competitively block the NUDEL-oligopeptidase activity in vitro. The Scottish DISC1 families are suggested to express a mutant form of DISC1 that does not bind NUDEL-oligopeptidase, implicating this enzyme in the underlying etiology of schizophrenia.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Procedures. Any animals used in experiments described herein were maintained and manipulated under strict ethical conditions, according to the International Animal Welfare Recommendations.

Materials. The internally quenched fluorogenic peptide qf-A6Bk4-9 [o-aminobenzoic acid-Gly-1-Phe-2-Ala-3-Pro-4-Phe-5-Arg-6-Gln-7-N-(2,4-dinitrophenyl) ethylenediamine] was synthesized and purified as described in ref. 18. Dr. Vincent Dive (Commissariat à l'Energie Atomique, Gif-sur-Yvette, France) kindly provided the phosphinic compound G-P-F-Ψ-(PO2CH2)-A-P-Nle (hereafter referred to as MO inhibitor), an active site-directed inhibitor for the metallo-oligopeptidases TOP (thiol-activated metallo-oligopeptidase) and NL (neurolysin) (19). The peptides bradykinin (Arg-1-Pro-2-Pro-3-Gly-4-Phe-5-Ser-6-Pro-7-Phe-8-Arg-9), dynorphin A1-8 (Tyr-1-Gly-2-Gly-3-Phe-4-Leu-5-Arg-6-Arg-7-Ile-8), and neurotensin (Gln-1-Leu-2-Tyr-3-Glu-4-Asn-5-Lys-6-Pro-7-Arg-8-Arg-9-Pro-10-Tyr-11-Ile-12-Leu-13) used as substrate were purchased from Peninsula Laboratories. The purity and the molecular masses of the recombinant proteins and peptides were determined by HPLC and by MALDI-TOF MS (TofSpec-E, Micromass, Manchester, U.K.), respectively. The antiserum anti-mouse DISC1 (α-DISC1) is described in ref. 7.

Cloning of Human and Rat Brain NUDEL-Oligopeptidase. The full-length cDNA coding for the human brain NUDEL-oligopeptidase was obtained from a human temporal cortex cDNA library (Stratagene), and the rat cDNA was obtained by RT-PCR from rat brain total RNA. See complete cloning details in Supporting Methods, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site. The amplified cDNA fragment encoding a full-length NUDEL-oligopeptidase was then subcloned in-frame into an expression plasmid vector, pET-21a (Novagen).

Preparation of Recombinant Proteins. The GST fusion cDNA of the truncated form of DISC1 used in this work was the same described by Brandon et al. (7). The expression and purification of human and rat brain recombinant NUDEL (rNUDEL)-oligopeptidase was performed as described for rabbit recombinant EOPA in ref. 11, except for the use of nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) instead of gluthatione-Sepharose beads. The eluted rNUDEL-oligopeptidase was resolved by HPLC (Shimadzu Class VP) by using a TSK-gel G 3000 SW column (7.5 mm ID × 60 cm, 10 μm particle size, TasoHaas, Montgomeryville, PA). The homogeneity was assessed by SDS/PAGE and HPLC. The molecular masses of the recombinant proteins obtained in this study were determined by Q-TOF MS (Micromass).

Site-Directed Mutagenesis of Human NUDEL-Oligopeptidase. Double-stranded site-directed mutagenesis of the human NUDEL-oligopeptidase to make the mutants C203A, C273A, and C293A was performed by overlap extension as described in ref. 20 in the pProEx HTc prokaryotic expression vector (Life Technologies, Rockville, MD). See Supporting Methods for a complete description.

Preparation of Polyclonal Antiserum Against rNUDEL-Oligopeptidase. Male High III mice (21) were immunized with homogeneous rNUDEL-oligopeptidase. The purified antibody was used as a specific NUDEL-oligopeptidase inhibitor and is abbreviated hereafter as NOAB (NUDEL-oligopeptidase antibody) inhibitor. The titration of antibodies against rNUDEL-oligopeptidase was evaluated by ELISA with rNUDEL-oligopeptidase-coated microtiter wells (Nunc-Immuno Plate MaxiSorp Surface, Nunc) as described in ref. 22.

Isolation of Proteolyticaly Active NUDEL-Oligopeptidase from Rat Brain Cytosol by Gel-Filtration Chromatography. The cytosol of rat brain was fractionated by gel-filtration chromatography on a Superose 12 column. (See Supporting Methods for a complete description.) The oligopeptidase activity of the fractions was determined fluorimetrically. The protein concentration of NUDEL-oligopeptidase, in the crude rat brain cytosol or in the gel-filtration fractions, was determined by sandwich ELISA (22) by using purified α-rNUDEL-oligopeptidase immunoglobulins (23).

Hydrolysis of Peptides by rNUDEL-Oligopeptidase. The relative rate of hydrolysis and the cleavage sites in bradykinin, dynorphin A1-8, and neurotensin were determined by HPLC (11). Briefly, the peptide solutions (30–50 μM) in 50 mM Tris·HCl buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.5 mM DTT were incubated with either rat brain or rNUDEL-oligopeptidase (≈1 milliunit) at 37°C and scissile bonds were determined by mass spectrometric analysis of the products after separation by reverse-phase HPLC (20).

Fluorimetric Assay for Hydrolysis of qf-A6Bk4-9. Hydrolyses of the quenched-f luorescent substrate qf-A6Bk4-9 by rNUDEL-oligopeptidase and by the gel-filtration fractions containing NUDEL-oligopeptidase were conducted as described in ref. 24. The cleavage site was determined as described above. One unit of oligopeptidase activity is the amount of enzyme that hydrolyses 1 μmol of qf-A6Bk4-9 in 1 min.

Inhibition of Oligopeptidase Activity by NUDEL-Oligopeptidase Antibody and by Recombinant DISC1 (rDISC1). Enzyme sample (recombinant or gel-filtration fractions) was preincubated for 30 min at 25°C with 20 μl of 1:100 dilution of NOAB inhibitor. Aliquots were removed and diluted in 50 mM Tris·HCl buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.5 mM DTT before the addition of the 5 μM quenched-fluorescence substrate (qf-A6Bk4-9). The elimination of peptidase activity from the NOAB inhibitor and the preimmune serum were performed by preincubation at 56°C for 5 min. The lack of anticatalytic activity in the preimmune serum was assured in control experiments. For inhibition by rDISC1, the enzyme concentration used was 90 nM; the concentrations of the substrate qf-A6Bk4-9 ranged from one to five times the Km value (see Table 2) to limit the extent of the hydrolysis to <10% of the substrate. The lack of rDISC1 catalytic activity was verified in control experiments. The concentrations of rDISC1 used for the Ki determinations were 35, 70, and 110 nM. This assay was performed in 50 mM Tris·HCl buffer (pH 7.4) containing 20 mM NaCl and 5 mM DTT. The type of inhibition was determined from Lineweaver–Burk plots (25). The Ki values were derived from the equations Ki = Ki(app)/(1+[S]/Km) and v0/vi = 1+[I]/Ki(app), as described in ref. 26.

Table 2. Effect of mutagenesis of cysteine residues in NUDEL-oligopeptidase on enzyme activity: kinetic parameters of fluorogenic peptide substrate qf-A6Bk4-9 hydrolyzed by human rNUDEL-oligopeptidase wild type and mutants.

| Enzyme | Km, μM | kcat, s-1 | kcat/Km, s-1·μM-1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 0.042 ± 0.001 | 17.5 |

| C203A | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 0.038 ± 0.001 | 17.3 |

| C273A | n.h. | n.h. | n.h. |

| C293A | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 0.041 ± 0.001 | 17.1 |

Fluorimetric assays were carried out in 1.0 ml of 50 mM Tris·HCl buffer (pH 7.4) containing 20 mM NaCl and 0.5 mM DTT at 37°C. The kinetic parameters were obtained in the presence of 1/10th to 10 times the Km value of peptide substrate and 50 nM rNUDEL-oligopeptidase, with a substrate consumption of <5%. The parameters were calculated as mean value ± SD. The peptide was cleaved only at peptide bond P ↓ F, which was determined by MS analyses (see Materials and Methods for details). All enzymatic assays were conducted in triplicate. n.h., no hydrolysis detected.

Results

Cloning and Characterization of Human EOPA. Human EOPA was cloned from a human brain cDNA library (see Materials and Methods and ref. 11), giving a full-length cDNA of ≈2.4 kb encoding a protein of 345 aa residues (Fig. 3, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). The alignment of this sequence with rabbit brain EOPA, human brain NUDEL, and rat NUDEL allowed verification that the sequence obtained in this work was identical to that of human NUDEL (Fig. 3). We therefore suggest the name NUDEL-oligopeptidase for this molecule.

To monitor the potential proteolytic activity of human rNUDEL-oligopeptidase, three biologically active oligopeptides of various sizes and amino acid sequences were used as substrates. The hydrolysis was monitored by HPLC, and the cleavage sites were deduced by mass spectrometric analysis of the products. Table 1 shows that human rNUDEL-oligopeptidase displays no restricted specificity for P1 or P1′ substrate position (27), because the enzyme cleaved the Phe-5↓Ser-6 bond of bradykinin, the Leu-5↓Arg-6 bond of dynorphin A1-8, and the Arg-9↓Arg-10 bond of neurotensin. Among these substrates, bradykinin was the most susceptible, whereas neurotensin showed the lowest velocity of hydrolysis.

Table 1. Hydrolysis of bioactive peptides by human rNUDEL-oligopeptidase.

| Assayed substrate | Rates of hydrolyses, nmol/μg/min | Cleavage site |

|---|---|---|

| Bradykinin | 23 | Phe-5 ↓ Ser-6 |

| Dynorphin A1-8 | 19 | Leu-5 ↓ Arg-6 |

| Neurotensin1-13 | 12 | Arg-8 ↓ Arg-9 |

Assays were carried out in 500 μl of 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) containing 20 mM NaCl and 0.5 mM DTT at 37°C. To determine the rate of hydrolysis, the reactions were conducted in the presence of 20 μM peptide substrate and 50 nM rNUDEL-oligopeptidase. Control samples were identical, except that rNUDEL-oligopeptidase was omitted. Reactions were stopped with 10 μl of trifluoroacetic acid, and the remaining peptide concentration was analyzed by HPLC as described in Materials and Methods. Velocity of hydrolysis was determined by comparison of substrates' peak areas of control and rNUDEL-oligopeptidase digested samples. The data represent the mean of three independent experiments.

NUDEL-Oligopeptidase Is a Cysteine Protease. To test the hypothesis that NUDEL-oligopeptidase is a cysteine protease, we initially were able to show that thiol compounds (e.g., DTT) have an activating effect, whereas thiol-reactive compounds, such as the Cys(Npys)-derived peptide, are irreversible inhibitors of the enzyme (Table 4, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). These results led us to mutate all three cysteine residues present in the rNUDEL-oligopeptidase molecule (Fig. 3) and to analyze their effect on the proteolytic activity of the respective recombinant proteins. The C273A mutant protein was totally inactive, whereas the other two mutant proteins (C203A and C293A) displayed kinetic data comparable to those obtained with the wild type (Table 2), confirming the presence of a cysteine catalytic group at the NUDEL-oligopeptidase active site. To verify that this loss of activity with the C273A mutation is not simply due to a disruption in the protein structure, we performed mass spectral and CD spectroscopic analyses for all of the proteins produced. The final CD spectra for the mutated proteins C203A, C273A, and C293A were similar to that of the corresponding wild-type recombinant protein, being in the experimental error determined with three independent analyses (see Supporting Methods; see also Table 5, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

Characterization of NUDEL-Oligopeptidase Activity in the Rat Brain. Because other oligopeptidases, such as TOP and NL, also hydrolyze the substrate qf-A6Bk4-9 (28), two distinct specific inhibitors were used to evaluate the contribution of NUDEL-oligopeptidase to peptidase activity in the rat brain: MO inhibitor [G-P-F-Ψ-(PO2CH2)-A-P-Nle, specific for TOP and NL (19)] and the NOAB inhibitor [a specific antibody inhibitor of NUDEL-oligopeptidase activity (11)]. The MO inhibitor does not block rNUDEL-oligopeptidase, whereas the NOAB inhibitor fully inhibited the enzymatic activity (Table 4). Moreover, preincubation of rat brain cytosol with MO inhibitor reduced the cytosolic oligopeptidase activity by 30%, whereas preincubation with NOAB inhibitor reduced the same activity by 50%. Combined, these two inhibitors had an additive effect, thus suggesting that the remaining activity (≈20%) in rat brain cytosol is not due to NUDEL-oligopeptidase, TOP, or NL (Table 3).

Table 3. Purification and characterization of NUDEL-oligopeptidase from rat brain cytosol.

| Activity, %

|

Total activity, milliunits

|

Protein, mg

|

NUDEL-oligopeptidase, μg

|

Specific activity, milliunits/μg

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme | -NOAB | +NOAB | ||||

| Cytosol plus MO inhibitor | 100 | 17 | 4.55 | 3.8 | 0.167 | 27.25 |

| Pool I | 2.2 | 2.4 | 0.42 | 0.7 | — | — |

| Pool II | 6.1 | 5.8 | 0.85 | 1.4 | — | — |

| Pool III | 4.1 | 4.2 | 0.46 | 0.9 | — | — |

| Pool IV | 3.8 | 2.3 | 0.21 | 0.7 | — | — |

| Pool V | 81.0 | 0.0 | 2.14 | 0.4 | 0.003 | 713.4 |

The protein concentration, the oligopeptidase activities of Pools I–V obtained from the experiment described in Fig. 1, and the susceptibilities of each pool to inhibition by the NOAB inhibitor are described in Materials and Methods. —, not determined.

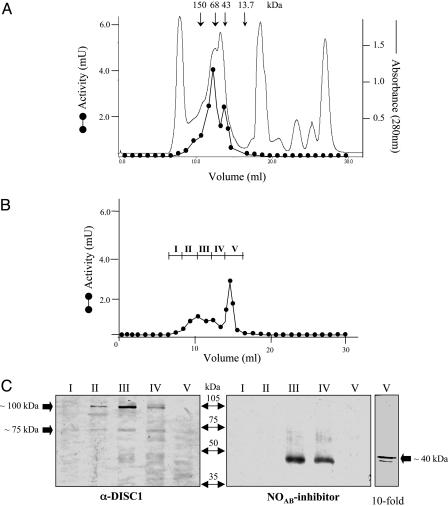

NUDEL-Oligopeptidase Monomer Is Responsible for Enzyme Activity. To identify the form of NUDEL-oligopeptidase responsible for enzyme activity, we performed gel-filtration chromatography using rat brain cytosol, which showed two peaks of peptidase activity with Mr corresponding to ≈75 and 40 kDa (Fig. 1A). When a similar assay was performed with the cytosol pretreated with the MO inhibitor (Fig. 1B), the peptidase activity of the 75-kDa peak was reduced by 80%, with the remaining activity slightly inhibited by the NOAB inhibitor (Table 3). In contrast, the 40-kDa activity peak (Pool V) was fully inhibited by the NOAB inhibitor and was not affected by the MO inhibitor (Table 3 and Fig. 1B). Western blot analysis of these fractions showed that NUDEL-oligopeptidase was highly enriched in fractions III and IV and slightly enriched in fraction V (corresponding to the 40-kDa peak) (Fig. 1C). Quantification of the immunoreactive NUDEL-oligopeptidase by sandwich ELISA showed that its monomer form (fraction V) corresponds to ≈1.8% of the total amount of this protein in the crude cytosol of rat brain (Table 3). The specific activity corresponding to the estimated concentration of NUDEL-oligopeptidase in fraction V was 713.4 milliunits/μg (Table 3). Interestingly, Western blot analysis of the same fractions for DISC1 showed the presence of a band of ≈100 kDa enriched in fraction III (Fig. 1C), where there is no appreciable NUDEL-oligopeptidase activity.

Fig. 1.

Determination of the active NUDEL-oligopeptidase species. (A) Profile of the oligopeptidase activities in different molecular mass fractions after gel-filtration chromatography of rat brain cytosol. (B) Oligopeptidase activities as in A, with the cytosol pretreated with MO inhibitor (see Methods). (C) Analysis of fractions by Western blotting for DISC1 (Left) and NUDEL-oligopeptidase (Center). The presence of the NUDEL-oligopeptidase in fraction V was detected only after a 10-fold amount of this fraction was loaded onto the gel (Right). The arrows indicate the positions of the Mr marker in kDa.

NUDEL-Oligopeptidase Activity Is Inhibited by Binding to DISC1. The catalytic cysteine at residue 273 is very close to the DISC1-binding site on NUDEL (centered on residues 266 and 267; Fig. 2C). To determine whether the binding of DISC1 to NUDEL-oligopeptidase has any effect on oligopeptidase activity, enzyme assays were conducted in the presence of recombinant DISC1 protein. DISC1 is shown to be efficient in inhibiting the rNUDEL-oligopeptidase activity in vitro in a competitive manner (Ki = 80 nM; Fig. 2 A). The presence of the qf-A6Bk4-9 substrate in the incubation medium reduced, in a concentration-dependent manner, the inhibitory effect of rDISC1 (Fig. 2 A).

Fig. 2.

DISC1 inhibits NUDEL-oligopeptidase activity. (A and B) Lineweaver–Burk plots (1/v versus 1/S) (A) and kinetic analyses (B) of rNUDEL-oligopeptidase inhibition by recombinant DISC1. The enzyme assays were performed by using qf-A6Bk4-9 as substrate and different fixed concentrations of rDISC1. All enzymatic assays were performed in triplicate. DISC1 competitively inhibits enzyme activity. (C) Diagram illustrating the Lis1 and DISC1 interaction domains on NUDEL-oligopeptidase. The position of the cysteines (C203, C273, and C293; arrows) and leucine-glutamate (L266/E267) residues, critical for interaction with DISC1, are indicated.

Discussion

The characterization of the enzyme NUDEL-oligopeptidase reported in this study suggests that this molecule may regulate neuropeptide levels relevant to the etiology of schizophrenia. Using a range of specific oligopeptidase inhibitors and biochemical fractionation techniques, we have shown that NUDEL-oligopeptidase activity is due to its monomeric form and depends on a catalytic cysteine at residue 273. We have previously characterized in detail the protein interaction domains between DISC1 and NUDEL-oligopeptidase and shown that the binding site on NUDEL-oligopeptidase depends on the residues L266 and E267 (7). In the current study, we identified the key catalytic residue as being just 6 aa away from the DISC1-binding site. This spatial proximity is likely to explain why the interaction between NUDEL-oligopeptidase and DISC1 completely abolishes the peptidase activity (see Fig. 2).

However, the loss of the proteolytic activity of NUDEL-oligopeptidase on protein binding may not be restricted to DISC1. In fact, the experiments presented in Fig. 1 and Table 3 suggest that NUDEL-oligopeptidase found in protein complexes of varying molecular weights does not possess enzyme activity. NUDEL-oligopeptidase has also been shown to bind to a number of other proteins, including 14-3-3ξ, which binds to Cdk5-phosphorylated NUDEL-oligopeptidase and protects the phosphoprotein from PP2A activity (16). More recently, NUDEL has also been implicated in NF assembly through a direct interaction with the NF light subunit (NF-L) (6). This interaction has been shown to be critical for the maintenance of neuronal architecture and integrity. Depletion of NUDEL by RNAi results in a concomitant down-regulation in NF-L and impairments in NF structure and function with a resultant change in neuronal morphology (6). It is possible that these interactions will have similar effects on peptidase activity, because the NF-L binding domain is mapped to amino acids 191–345, and 14-3-3ξ is mapped to amino acids 189–256 of NUDEL (6, 16). These domains are overlapping or in close proximity to the DISC1-binding site centered on residues 266 and 267 and the critical Cys residue at 273. It will be of great interest to look at the effects of NF-L and 14-3-3ξ binding on the peptidase activity. Supporting this theory, the Lis1 binding domain on NUDEL-oligopeptidase is quite distinct from the catalytic region around Cys-273 (Fig. 2C), and we have preliminary data showing that the interaction with Lis1 does not modulate NUDEL-oligopeptidase activity.

Interestingly, NUDEL-oligopeptidase has been shown, in vitro, to cleave a number of neuropeptides, some of which have been previously implicated in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia, including neurotensin (NT). Neurotensin receptor agonists have been recently suggested to be potential antipsychotics (see refs. 30 and 31 for reviews). Inhibition of NUDEL-oligopeptidase could lead to increases in the local concentration of NT, with a possible antipsychotic effect. Interestingly, levels of NT have been shown to increase with antipsychotic treatment, as do levels of proenkephalin products (29, 32–34) that are also NUDEL-oligopeptidase substrates. The effects of known antipsychotics on NUDEL-oligopeptidase activity should thus be investigated as a possible explanation for their effects in the CNS. We have no evidence at the moment, though, of the function and substrates of NUDEL-oligopeptidase in vivo.

In conclusion, we have tentatively identified NUDEL-oligopeptidase as a possible molecular player in psychosis. The translocation in the DISC1 gene, observed to cosegregate with schizophrenia in a Scottish family, may produce a truncated DISC1 protein that is unable to bind NUDEL (7, 9) or potentially result in DISC1 haploinsufficiency. Regardless of the genetic model, the downstream effects of this translocation could be an increase in NUDEL-oligopeptidase activity, in turn leading to alterations in the levels of the substrates of NUDEL-oligopeptidase. It must be emphasized, though, that we currently have no evidence that NUDEL-oligopeptidase activity is altered in members of the Scottish DISC1 family or in schizophrenics in the general population. Future experiments that measure the activity of NUDEL-oligopeptidase in patients versus controls could provide critical information for understanding the etiology of schizophrenia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Neusa Lima for secretarial assistance and Maria Aparecida Siqueira and Aparecida das Dores Coelho for technical assistance. This work was supported by the Fundação de Amparo `a Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo through the Center for Applied Toxinology–Centro de Pesquisa, Inovação e Difusão Program.

Author contributions: M.A.F.H., F.C.V.P., and A.C.M.C. designed research; M.A.F.H., F.C.V.P., M.F.B., J.R.G., V.O., and S.S.G. performed research; M.A.F.H., F.C.V.P., V.O., K.K., and A.C.M.C. analyzed data; M.A.F.H., F.C.V.P., P.J.W., L.M.C., N.J.B., and A.C.M.C. wrote the paper; O.A.S. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; D.V.T. performed and standardized the sandwich ELISA experiments used for the quantification of the protein in the free form; O.A.S. developed the antibodies and provided the hyperimmune mice; and V.O. and K.K. performed MS spectra analyses.

Abbreviations: EOPA, endooligopeptidase A; NUDEL, nuclear distribution element-like; NUDEL-oligopeptidase, NUDEL or EOPA; Lis1, lissencephaly gene 1 product; DISC1, disrupted-in-schizophrenia 1 gene product; TOP, thiol-activated metallo-oligopeptidase (EC 3.4.24.15); NL, neurolysin (EC 3.4.24.16); NOAB, NUDEL-oligopeptidase antibody; rNUDEL, recombinant NUDEL; rDISC1, recombinant DISC1; NF, neurofilament; MO inhibitor, G-P-F-Ψ-(PO2CH2)-A-P-Nle.

Data deposition: The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the GenBank database (accession no. AF217798).

References

- 1.Efimov, V. P. & Morris, N. R. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 150, 681-688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kitagawa, M., Umezu, M., Aoki, J., Koizumi, H., Arai, H. & Inoue, K. (2000) FEBS Lett. 479, 57-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niethammer, M., Smith, D. S., Ayala, R., Peng, J., Ko, J., Lee, M. S., Morabito, M. & Tsai, L. H. (2000) Neuron 28, 697-711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sasaki, S., Shionoya, A., Ishida, M., Gambello, M. J., Yingling, J., Wynshaw-Boris, A. & Hirotsune, S. (2000) Neuron 28, 681-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sweeney, K. J., Prokscha, A. & Eichele, G. (2001) Mech. Dev. 101, 21-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen, M. D., Shu, T., Sanada, K., Lariviere, R. C., Tseng, H. C., Park, S. K., Julien, J. P. & Tsai, L. H. (2004) Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 595-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brandon, N. J., Hanford, E. J., Schurov, I., Rain, J.-C., Pelling, M., Duran-Jimeniz, B., Camargo, M., Oliver, K. R., Beher, D., Shearman, M. S. & Whiting, P. J. (2004) Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 25, 42-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris, J. A., Kandpal, G., Ma, L. & Austin, C. P. (2003) Hum. Mol. Genet. 12, 1591-1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozeki, Y., Tomoda, T., Kleiderlein, J., Kamiya, A., Bord, L., Fujii, K., Okawa, M., Yamada, N., Hatten, M. E., Snyder, S. H., et al. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 289-294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Millar, J. K., Christie, S., Anderson, S., Lawson, D., Hsiao-Wei Loh, D., Devon, R. S., Arveiler, B., Muir, W. J., Blackwood, D. H. & Porteous, D. J. (2001) Mol. Psychiatry 6, 173-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayashi, M. A. F., Portaro, F. C. V., Tambourgi, D. V., Sucupira, M., Yamane, T., Fernandes, B. L., Ferro, E. S., Rebouças, N. A. & Camargo, A. C. M. (2000) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 269, 7-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayashi, M. A. F., Portaro, F. C. V. & Camargo, A. C. M. (2004) Curr. Med. Chem. Central Nervous System 4, 269-277. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Camargo, A. C. M., Reis, M. L. & Caldo, H. (1979) J. Biol. Chem. 254, 5304-5307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Camargo, A. C., Oliveira, E. B., Toffoletto, O., Metters, K. M. & Rossier, J. (1987) J. Neurochem. 48, 1258-1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leventer, R. J., Cardoso, C., Ledbetter, D. H. & Dobyns, W. B. (2001) Trends Neurosci. 24, 489-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toyo-oka, K., Shionoya, A., Gambello, M. J., Cardoso, C., Leventer, R., Ward, H. I., Ayala, R., Tsai, L-H., Dobyns, W., Ledbetter, D., et al. (2003) Nat. Genet. 14, 274-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomes, M. D., Juliano, L., Ferro, E. S., Matsueda, R. & Camargo, A. C. M. (1993) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 197, 501-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirata, I. Y., Cezari, M. H., Nakaie, C. R., Boschcov, P., Ito, A. S., Juliano, M. A. & Juliano, L. (1994) Lett. Pept. Sci. 1, 299-308. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiracek, J., Yiotakis, A., Vincent, B., Lecoq, A., Nicolaou, A., Checler, F. & Dive, V. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 21701-21706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Portaro, F. C. V., Hayashi, M. A. F., Arauz, L. J., Palma, M. S., Assakura, M. T., Silva, C. L. & Camargo, A. C. M. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 7400-7406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sant'Anna, O. A., Bouthillier, Y., Mevel, J. C., de-Franco, M. & Mouton, D. (1991) Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 24, 407-416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ausubel, F. M., Brent, R., Kingston, R. E., Moore, D. D., Seidman, J. G., Smith, J. A. & Struhl, K. (1990) Current Protocols in Molecular Biology (Greene & Wiley, New York), Unit 11.

- 23.Russ, C., Callegaro, I., Lanza, B. & Ferrone, S. (1983) J. Immunol. Methods 65, 269-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oliveira, V., Araujo, M. C., Rioli, V., Camargo, A. C. M., Tersariol, I. L. S., Juliano, M. A., Juliano, L. & Ferro, E. S. (2003) FEBS Lett. 541, 89-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Segel, I. H. & Martin, R. L. (1975) J. Theor. Biol. 135, 445-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicklin, M. J. & Barrett, A. J. (1984) Biochem. J. 223, 245-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schechter, I. & Berger, A. (1967) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 27, 157-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oliveira, V., Campos, M., Hemerly, J. P., Ferro, E. S., Camargo, A. C., Juliano, M. A. & Juliano, L. (2001) Anal. Biochem. 292, 257-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Binder, E. B., Kinkead, B., Owens, M. J. & Nemeroff, C. B. (2001) Biol. Phychiatry 50, 856-872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caceda, R., Kinkead, B. & Nemeroff, C. B. (2003) Semin. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 8, 94-108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kinkead, B. & Nemeroff, C. B. (2004) Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 59, 327-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fox, K. (1994) J. Neurosci. 14, 7665-7679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merchant, K. M., Dobie, D. J., Filloux, F. M., Totzke, M., Aravagiri, M. & Dorsa, D. M. (1994) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 271, 460-471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bauer, R., Mayr, A., Lederer, W., Needham, P. L., Kilpatrick, I. C., Fleischhacker, W. W. & Marksteiner, J. (2000) Neuropsychopharmacology 23, 46-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.