Abstract

Glutamatergic neurotransmission within the brain’s reward circuits plays a major role in the reinforcing properties of both ethanol and cocaine. Glutamate homeostasis is regulated by several glutamate transporters, including glutamate transporter type 1 (GLT-1), cystine/glutamate transporter (xCT), and glutamate aspartate transporter (GLAST). Cocaine exposure has been shown to induce a dysregulation in glutamate homeostasis and a decrease in the expression of GLT-1 and xCT in the nucleus accumbens (NAc). In this study, alcohol preferring (P) rats were exposed to free-choice of ethanol (15% and 30%) and/ or water for five weeks. On Week 6, rats were administered (i.p.) cocaine (10 and 20 mg/kg) or saline for 12 consecutive days. This study tested two groups of rats: the first group was euthanized after seven days of repeated cocaine i.p. injection, and the second group was deprived from cocaine for five days and euthanized at Day 5 after cocaine withdrawal. Only repeated cocaine (20 mg/kg, i.p.) exposure decreased ethanol intake from Day 3 through Day 8. Co-exposure of cocaine and ethanol decreased the relative mRNA expression and the expression of GLT-1 in the NAc but not in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). Importantly, co-exposure of cocaine and ethanol decreased relative expression of xCT in the NAc but not in the mPFC. Our findings demonstrated that chronic cocaine exposure affects ethanol intake; and ethanol and cocaine co-abuse alters the expression of glial glutamate transporters.

Keywords: GLT-1, xCT, GLAST, mGluRs, mPFC, NAc

INTRODUCTION

A meta-analysis study revealed quantitatively that cues associated with ethanol and cocaine dependence activate common brain region (Kuhn and Gallinat, 2011). Studies, conducted on inpatients, showed that there is a high concurrence of ethanol dependence in patients diagnosed with cocaine dependence (Miller et al., 1989). A large portion of cocaine-dependent patients has also been reported to counteract cocaine –withdrawal symptoms with ethanol (Magura and Rosenblum, 2000). Furthermore, relapse to cocaine and/or ethanol intake was higher in individuals with co-abuse problems (Fox et al., 2005). In addition, the cocaine reinforcing effect was found evident in high ethanol drinking rats compared to low ethanol drinking rats (Stromberg and Mackler, 2005).

Glutamatergic neurotransmission in the mesocorticolimbic circuit has been found to mediate the reinforcing properties of drugs of abuse [For review see ref. (Adinoff, 2004)]. The altered glutamatergic efferent of the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) into the nucleus accumbens (NAc) contributes significantly to compulsive drug-seeking behavior (Riga et al., 2014). Importantly, alteration in postsynaptic glutamate clearance facilitated chronic drug use and drug- seeking behavior (Fujio et al., 2005, Melendez et al., 2005, Knackstedt et al., 2010b, Das et al., 2015). Extracellular glutamate concentration was increased significantly following ethanol exposure in the NAc (Dahchour et al., 2000) and the ventral tegmental area (Ding et al., 2013) in rat animal models. Similarly, non-contingent cocaine exposure increased extracellular glutamate concentrations in the NAc (Gass and Olive, 2008).

The extracellular glutamate concentration is tightly maintained within the physiological range through glutamate transporters/antiporters. Glutamate transporter 1 (GLT-1), one of the five subtypes of amino acid transporters, contributes to clearing the majority of this extracellular glutamate (Danbolt, 2001). In contrast, glutamate-cystine exchanger (xCT) contributes to extracellular glutamate through pumping out glutamate in exchange for cystine (Bannai and Ishii, 1982, Bannai et al., 1984). Studies from ours and others have reported that GLT-1 was downregulated in the NAc following exposure to several drugs of abuse, including ethanol and cocaine (Ginsberg et al., 1995, Danbolt, 2001, Knackstedt et al., 2009, Sari and Sreemantula, 2012, Fischer et al., 2013, Shen et al., 2014). Importantly, a study from our laboratory showed that sequential exposure to ethanol and repeated high dose methamphetamine caused additive downregulation of GLT-1 in the NAc than either drug exposed alone (Althobaiti et al., 2016).

Repeated cocaine exposure has been shown to reduce xCT activity and reversal of this activity by pretreatment of N-acetylcysteine prevented compulsive cocaine-seeking (Madayag et al., 2007). In addition, chronic consumption of ethanol downregulated both xCT and GLT-1 expression in the NAc (Alhaddad et al., 2014, Das et al., 2015). Therefore, we hypothesized that non-contingent cocaine exposure during continuous ethanol drinking might have an augmented effect on the expression of glutamate transporters in mesocorticolimbic regions of alcohol-preferring (P) rats. Moreover, little is known about the expression level of glutamate transporters following repeated cocaine administration and continuous ethanol drinking. In this study, we proposed to test the effects of repeated cocaine exposure and withdrawal on ethanol free-choice drinking and expression of glutamate transporters in both the NAc and mPFC of P rats.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Male P rats were obtained from Indiana University, School of Medicine (Indianapolis, IN, USA) at the age of 21–30 days, and housed in the Department of Laboratory Animal Resources, University of Toledo, Health Science Campus. At the age of 75 days, rats were individually housed in a plastic corncob bedding tubs and had a free access to food and water ad lib. The room temperature was maintained at 21°C and 50% humidity with a 12-hour light-dark cycle. All animal procedures were in compliance and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use committee of The University of Toledo in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Institutes of Health and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, Commission on Life Sciences, 1996).

Behavioral drinking paradigms

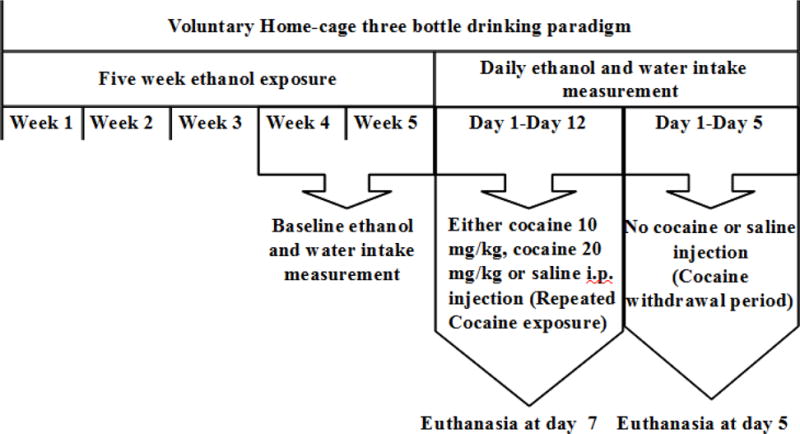

Time-line, for voluntary ethanol drinking and repeated cocaine exposure and withdrawal, is illustrated in Fig. 1. Rats were exposed to voluntary home-cage three bottle drinking paradigm (free choice of ethanol 15% and 30% and water) for a period of five weeks. Introducing two concentrations of ethanol, along with water, has been shown to increase voluntary ethanol consumption level (Bell et al., 2006). After the third week of drinking paradigm, ethanol and water intakes were measured three times a week for two weeks and used as a baseline. Ethanol and water intake measurements were expressed as g/kg/day. Animals, that drank less than 4 g/kg/day of ethanol, were excluded from the study in accordance to studies from our laboratory (Sari et al., 2011, Sari and Sreemantula, 2012, Sari et al., 2013). On Week 6, P rats were randomly divided into four groups: 1) ethanol- naive (water control) group had continuous access to water only throughout the study and received saline vehicle injection (i.p.); 2) ethanol- saline group had continuous access to ethanol and water throughout the study and received saline vehicle (i.p.) injection; 3) ethanol-cocaine 10 mg/kg group had continuous access to ethanol and water throughout the study and received cocaine 10 mg/kg (i.p.) injection; 4) and ethanol-cocaine 20 mg/kg group had continuous access to ethanol and water throughout the study and received cocaine 20 mg/kg (i.p.) injection. Starting Day 1 of Week 6, one set of rats, were given injections (i.p.) of either saline or cocaine for seven consecutive days and euthanized during repeated cocaine exposure (see Fig. 1). Second set of rats was given injections (i.p.) of either saline or cocaine for 12 consecutive days then deprived from cocaine for five days and euthanized at Day 5 of cocaine withdrawal (see Fig. 1). Euthanized time points were chosen to investigate the contribution of glutamate transporters expression to the decrease and normalization in ethanol consumption during cocaine administration and cocaine deprivation, respectively. On week 6, ethanol and water intake were measured daily as g/kg of body weight /day. Weights of bottles were measured and the amount of intake was determined to the nearest tenth of gram by subtracting the obtained bottle weight from their previous day’s value. Bottles were changed twice a week. We used two doses of cocaine: 10 and 20 mg/kg. The cocaine 10 mg/kg dose is sufficient to impart behavioral effect of cocaine (increased locomotion) in rats (Filip et al., 2003). Previous study also demonstrated that repeated cocaine (20 mg/ kg, i.p.) exposure resulted in altered glutamate transmission and clearance in striatum of rats (Parikh et al., 2014). Moreover, withdrawal from repeated cocaine administration (15–30 mg/kg, i.p.) blunted xCT activity, which in turn reduced extracellular glutamate concentration in the NAc of rats (Baker et al., 2003).

FIGURE 1.

Time-line for voluntary ethanol drinking and repeated cocaine exposure and withdrawal.

Brain tissue harvesting

Rats were euthanized using carbon dioxide in two different time points (Day 7 of cocaine exposure and Day 5 of cocaine withdrawal) and directly decapitated using guillotine. Brains were then immediately placed on dry ice and stored at −80°C. The mPFC and the NAc were then dissected using a cryostat apparatus set at −20 °C. Brain regions were identified according to the Rat Brain Atlas (Paxinos, 1997). Extracted brain regions were stored at −80°C for Western blot analysis.

Western Blot

Brain regions were lysed using regular lysis buffer as described in previous study from our laboratory (Sari et al., 2011). Equal amounts of extracted proteins were mixed with 5X laemmli loading dye and then were separated in 10% polyacrylamide gels. Proteins were then transferred on a PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Membranes were then blocked with 3% milk in TBST (50 mM Tris HCl; 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4; 0.1% Tween 20) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Membranes were then incubated overnight at 4°C with one of the following primary antibodies: guinea pig anti-GLT-1 (1:5000, Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents), rabbit anti-xCT antibody (1: 1,000; Abcam), and rabbit anti-EAAT1 (GLAST) antibody (1: 5,000; Abcam). Mouse anti β-tubulin was used as loading control (1:5,000; Cell signaling technology). After incubation with primary antibodies, membranes were then washed with TBST for five times and then blocked with 3% milk in TBST for 30 minutes. Membranes were further incubated with secondary antibody for 90 minutes at room temperature. Secondary antibodies were anti-mouse (1:5,000; Cell signaling technology), anti-rabbit (1:5000; Thermo scientific) and anti-guinea pig (1:5,000; Cell signaling technology). Membranes were then incubated with the SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent substrate and further exposed to Kodak BioMax MR Film (Fisher Inc.); and films were developed on SRX-101A machine. MCID system was used to quantify the detected bands, and the results were presented as a percentage of the ratio of tested protein/ β-tubulin, relative to ethanol- naïve (water) control groups (100% control-value).

Real-Time, quantitative PCR (RT-PCR, qPCR)

Total RNAs were isolated from the NAc and the mPFC using TRizol reagent (Invitrogen# 15596-018). Reverse transcription (RT) was carried out using Thermo Scientific verso cDNA synthesis kit (cat#AB-1453/A) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The Real-Time PCR was performed using an iCycler (Bio-Rad laboratories, München, Germany) containing a reaction mixture of SYBR Green as fluorescent dye (BIO-RAD, #170-8882), a 1/20 volume of the cDNA preparation as a template and the appropriate primers for the genes of interest as shown in Table 1. The obtained threshold cycle number (CT) for each sample was used to compare the relative amount of target mRNA in experimental groups to those of controls using the 2−ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Each sample was run in triplicate. The mean CT value for control gene (GAPDH) was subtracted from the mean CT value of the gene of interest to get ΔCT. The ΔCT values for the control group (ethanol-naive) were then averaged and subtracted from the ΔCT for the experimental groups to obtain the ΔΔCT. The relative fold change from control was then expressed by calculation of 2−ΔΔCT for each sample and the results were reported as the group mean fold change ± SEM.

Table 1.

Primer sequence for rat glutamate transporters and metabotropic receptors

| Gene | Primer | Sequence a, b |

|---|---|---|

| GLT1 | Forward primer | 5′-GAGCATTGGTGCAGCCAGTATT-3′ |

| Reverse primer | 5′-GTTCTCATTCTATCCAGCAGCCAG-3′ | |

| GLAST | Forward primer | 5′-CCTGGGTTTTCATTGGAGGG-3′ |

| Reverse primer | 5′-ATGCGTTTGTCCACACCATTG-3′ | |

| xCT | Forward primer | 5′-ACCTTTTGCAAGCTCACAGCAA -3′ |

| Reverse primer | 5′-AGCAGGAGAGGGCAACAAAGAT -3′ | |

| GAPDH | Forward primer | 5′-CCCCCAATGTATCCGTTGTG-3′ |

| Reverse primer | 5′-TAGCCCAGGATGCCCTTTAGT-3′ |

GLT-1, GLAST and GAPDH primers’ sequence were used as reported previously (Tawfik et al., 2006).

xCT primer sequence was used as reported previously (Baker et al., 2003).

Statistical analyses

Two-way mixed model ANOVA with repeated measure at each time point, followed by Newman-Keuls multiple comparisons, was used to analyze drinking measurements, relative mRNA expression and Western blot data. All statistical analyses were based on a p<0.05 level of significance.

RESULTS

Effects of repeated cocaine exposure and withdrawal on ethanol intake, water intake and body weight

Average daily ethanol intake

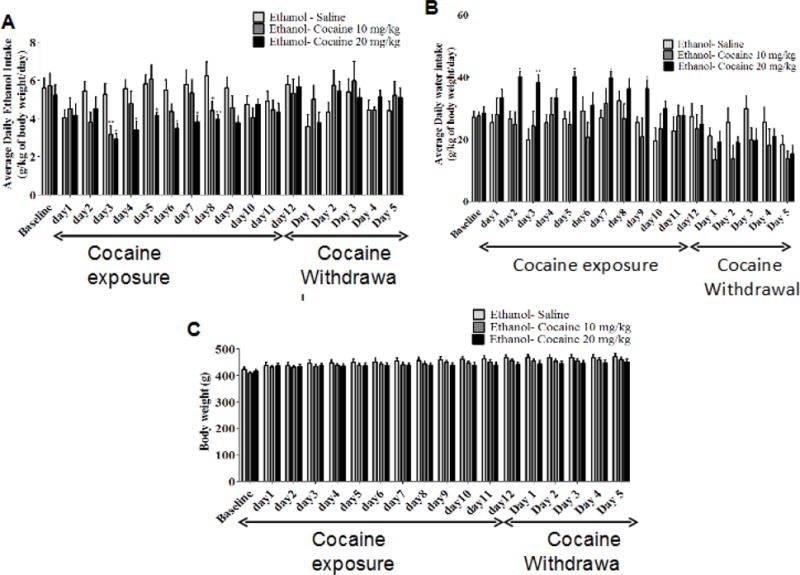

Two-way mixed model ANOVA with repeated measure at each time point revealed a significant main effect of Days [F (17, 357) = 4.722, p < 0.0001], a non-significant effect of Treatment [F (2, 357) = 0.9907, p = 0.3880], and a significant Day × Treatment interaction [F (34, 357) = 3.097, p < 0.0001]. Newman-Keuls multiple comparisons test revealed a significant reduction in average daily ethanol intake in rats treated with cocaine 20 mg/kg starting on Day 3 through Day 8, compared to the saline-treated P rats. Cocaine 10 mg/kg significantly reduced average ethanol intake on Day 3, and Day 8 as compared to the saline treated rats (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 2.

Average daily ethanol consumption, water intake and body weight in male P rats (mean ± SEM) during the baseline (Week 4 and 5), repeated cocaine exposure (Day 1–Day 12) and cocaine withdrawal (Day1–Day 5) periods of the study. A) Two-way mixed model ANOVA with repeated measure at each time point revealed a significant reduction in average ethanol daily intake in animals treated with cocaine (20 mg/kg, i.p.) starting on Day 3 and lasting through Day 8, compared to the saline-treated P rats. Cocaine (10 mg/kg, i.p.) significantly reduced average ethanol daily intake only on Day 3 and Day 8. B) Two-way mixed model ANOVA with repeated measure at each time point revealed a significant reduction in the average daily water intake in animals treated with cocaine (20 mg/kg, i.p.) starting on Day 2, Day 3, Day 5, Day 7 and Day 9, compared to the saline-treated P rats. C) Two-way mixed model ANOVA with repeated measure at each time point revealed a non-significant effect in animals treated with either cocaine (10 or 20 mg/kg, i.p.) compared to the saline-treated P rats (*: p<0.05, **: p<0.01), (n= 8 for each group).

Average daily water intake

Two-way mixed model ANOVA with repeated measure at each time point revealed a significant main effect of Days [F (17, 357) = 8.637, p < 0.0001], a non-significant effect of treatment [F (2, 357) = 1.967, p = 0.1649], and a significant Day × Treatment interaction [F (34, 357) = 2.57, p < 0.0001]. Newman-Keuls multiple comparisons test revealed a significant decrease in average water daily intake in animals treated with cocaine 20 mg/kg starting on Day 2, Day 3, Day 5, Day 7 and Day 9, compared to the saline-treated P rats (Fig. 2B).

Average body weight

Two-way mixed model ANOVA with repeated measure at each time point revealed a significant main effect of Days [F (17, 357) = 48.7, p < 0.0001], a non-significant effect of Treatment [F (2, 357) = 0.7274, p = 0.4949], and a significant Day × Treatment interaction [F (34, 357) = 2.323, p < 0.0001]. Newman-Keuls multiple comparisons test revealed a non-significant effect in body weight of animals treated with cocaine (10 or 20 mg/kg, i.p.) compared to the saline-treated P rats (Fig. 2C).

Effects of repeated cocaine exposure and withdrawal on relative mRNA expression of glial glutamate transporters in the NAc and mPFC

Relative mRNA expression of GLT-1, xCT and GLAST in the NAc

GLT-1 mRNA

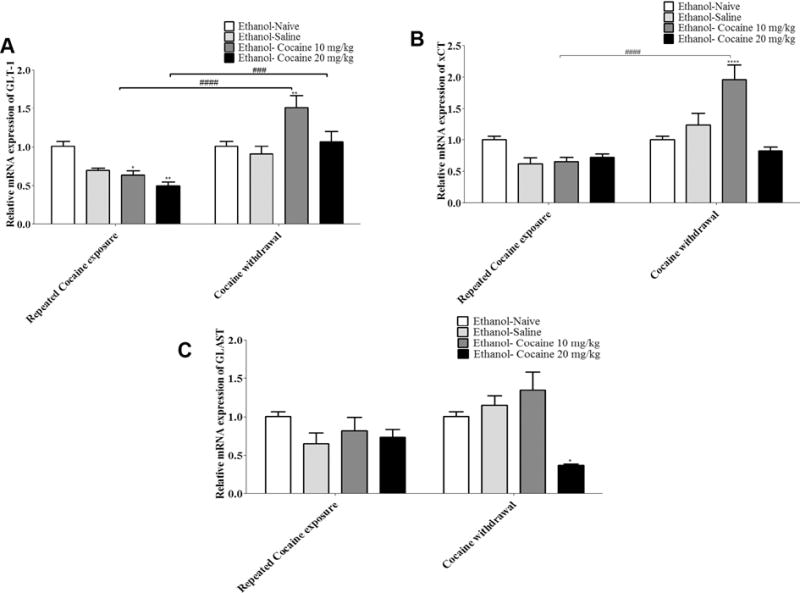

Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of Days [F (1, 16) = 50.52, p <0.0001], a significant main effect of Treatment [F (3, 16) = 4.667, p = 0.0158], and a significant Day × Treatment interaction [F (3, 16) = 11.02, p = 0.0004] in the NAc (Fig. 3A). Newman-Keuls multiple comparisons test revealed a significant reduction in relative GLT-1 mRNA expression in the NAc of rats treated with cocaine (10 or 20 mg/kg, i.p.) compared to ethanol-naïve (water control) P rats during repeated cocaine exposure (at Day 7 of repeated cocaine exposure). A significant increase in relative GLT-1 mRNA expression in the NAc was revealed in animals treated with cocaine 10 mg/kg as compared to ethanol-naïve P rats (water control) after five days of cocaine withdrawal. A significant increase in relative GLT-1 mRNA expression in the NAc was found in rats treated with cocaine (10 or 20 mg/kg, i.p.) after five days of cocaine withdrawal compared to cocaine repeated exposure (Fig. 3A, p < 0.05 for cocaine 10 mg/kg and p < 0.01 for cocaine 20 mg/kg).

FIGURE 3.

Relative mRNA expression of GLT-1, xCT and GLAST in the NAc at two different time points (after 7 days of repeated cocaine exposure and after 5 days of cocaine withdrawal) (mean ± SEM). A) Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant reduction in relative GLT-1 mRNA expression in animals treated with cocaine (10 mg/kg, i.p.) and animals treated with cocaine (20 mg/kg, i.p.), respectively compared to ethanol-naïve P rats during repeated cocaine exposure. A significant increase was also revealed in relative GLT-1 mRNA expression in animals treated with cocaine (10 mg/kg, i.p.) as compared to ethanol-naïve P rats after five days of cocaine withdrawal. A significant increase in relative GLT-1 mRNA expression was found in animal treated with cocaine (10 or 20 mg/kg, i.p.) after five days of cocaine withdrawal compared to cocaine repeated exposure. B) Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant increase in relative xCT mRNA expression in animals treated with cocaine (10 mg/kg, i.p.) compared to ethanol-naïve P rats after five days of cocaine withdrawal. A significant increase in relative xCT mRNA expression was shown with animal treated with cocaine (10 mg/kg, i.p.) after five days of cocaine withdrawal compared to cocaine repeated exposure. C) Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant decrease in relative GLAST mRNA expression in animals treated with cocaine (20 mg/kg, i.p.) compared to ethanol-naïve P rats after five days of cocaine withdrawal (*: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ###: p<0.001, ####: p<0.0001), (n=5 for each group).

xCT mRNA

Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of Days [F (1, 16) = 29.77, p < 0.0001], a significant main effect of Treatment [F (3, 16) = 6.803, p = 0.0036], and a significant Day × Treatment interaction [F (3, 16) = 12.68, p = 0.0002] in the NAc (Fig. 3B). Newman-Keuls multiple comparisons test revealed a significant increase in relative xCT mRNA expression in the NAc in animals treated with cocaine 10 mg/kg (i.p.) compared to ethanol-naïve P rats after five days of cocaine withdrawal. A significant increase in relative xCT mRNA expression in the NAc was found in animal treated with cocaine 10 mg/kg (i.p.) after five days of cocaine withdrawal compared to cocaine repeated exposure (Fig. 3B, p < 0.001).

GLAST mRNA

Two-way ANOVA revealed a non-significant main effect of Days [F (1, 16) = 1.803, p = 0.1981], a significant main effect of Treatment [F (3, 16) = 9.282, p = 0.0009], and a significant Day × Treatment interaction [F (3, 16) = 3.332, p = 0.0462] in the NAc (Fig. 3C). Newman-Keuls multiple comparisons test revealed a significant decrease in relative GLAST mRNA expression in the NAc in animals treated with cocaine 20 mg/kg (i.p.) compared to ethanol-naïve P rats after five days of cocaine withdrawal (Fig. 3C, p < 0.001).

Relative mRNA expression of GLT-1, xCT and GLAST in the mPFC

Two-way ANOVA did not reveal any significant difference in the relative mRNA expression of GLT-1, xCT and GLAST in the mPFC of groups during repeated cocaine exposure or cocaine withdrawal (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Relative mRNA expression of GLT-1, xCT and GLAST in the mPFC at two different time points (after 7 days of repeated cocaine exposure and after 5 days of cocaine withdrawal). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. (n=5 for each group).

| Group | GLT-1 | xCT | GLAST | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water control group | Ethanol-Naive | 1.002 ± 0.03 | 0.920 ± 0.08 | 1.007 ± 0.06 |

| Repeated Cocaine exposure | Ethanol-Saline | 0.825 ± 0.09 | 1.078 ± 0.10 | 1.092 ± 0.07 |

| Ethanol-Cocaine 10 mg/kg | 1.083 ± 0.11 | 1.030 ± 0.15 | 1.031 ± 0.11 | |

| Ethanol-Cocaine 20 mg/kg | 1.106 ± 0.06 | 0.686 ± 0.06 | 1.062 ± 0.07 | |

| Cocaine withdrawal | Ethanol-Saline | 0.913 ± 0.07 | 0.885 ± 0.15 | 0.996 ± 0.06 |

| Ethanol-Cocaine 10 mg/kg | 1.034 ± 0.06 | 0.891 ± 0.09 | 1.066 ± 0.09 | |

| Ethanol-Cocaine 20 mg/kg | 1.118 ± 0.08 | 1.075 ± 0.14 | 1.042 ± 0.12 |

Effects of repeated cocaine exposure and withdrawal on glutamate transporters expression in the NAc and mPFC

GLT-1, xCT and GLAST expression in the NAc

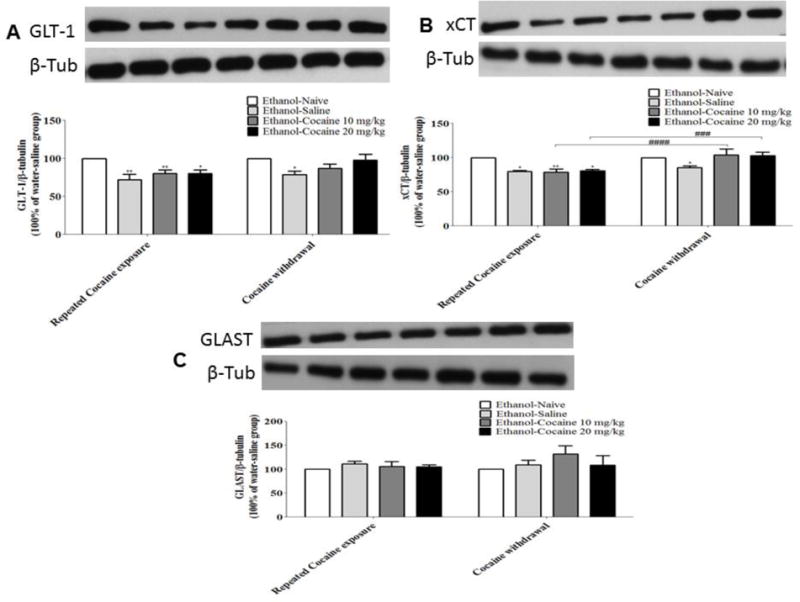

GLT-1

Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of Days [F (1, 16) = 4.601, p = 0.0477], a significant main effect of Treatment [F (3, 16) = 7.974, p = 0.0018], and a non-significant Day × Treatment interaction [F (3, 16) = 1.004, p = 0.4166]. Newman-Keuls multiple comparisons test revealed a significant reduction in GLT-1 expression in animals treated with saline, cocaine 10 mg/kg or cocaine 20 mg/kg compared to ethanol-naïve P rats during repeated cocaine exposure (Fig. 4A, p < 0.05). A significant decrease in GLT-1 expression was found in the NAc in animals treated with saline compared to ethanol-naïve P rats after five days of cocaine withdrawal (Fig. 4A, p < 0.01).

FIGURE 4.

GLT-1, xCT and GLAST expression in the NAc at two different time points (after 7 days of repeated cocaine exposure and after 5 days of cocaine withdrawal) (mean ± SEM). A) Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant reduction in GLT-1 expression in animals exposed to either ethanol alone or in combination with cocaine 10 mg/kg or 20 mg/ kg compared to ethanol-naïve P rats during repeated cocaine exposure. A significant decrease in GLT-1 expression was also revealed in animals exposed to ethanol as compared to ethanol-naïve P rats after five days of cocaine withdrawal. B) Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant reduction in xCT expression in animals exposed to either ethanol alone or in combination with cocaine 10 mg/kg or 20 mg/ kg as compared to ethanol-naïve P rats during repeated cocaine exposure. A significant decrease was also revealed in xCT expression in animals exposed to ethanol compared to ethanol-naïve P rats after five days of cocaine withdrawal. C) Two-way ANOVA revealed a non-significant effect of either ethanol exposure alone or combined with cocaine 10 mg/kg or 20 mg/kg on GLAST expression (*: p<0.05, **: p<0.01, ###: p<0.001, ####: p<0.0001), (n=5 for each group).

xCT

Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of Days [F (1, 16) = 45.28, p < 0.0001], a significant main effect of treatment [F (3, 16) = 3.534, p = 0.0.0389], and a significant Day × Treatment interaction [F (3, 16) = 9.559, p = 0.0007]. Newman-Keuls multiple comparisons test revealed a significant decrease in xCT expression in the NAc in animals treated with cocaine 10 mg/kg compared to ethanol-naïve P rats after five days of cocaine withdrawal. A significant increase in relative xCT mRNA expression was shown in the NAc in animal treated with cocaine 10 mg/kg after five days of cocaine withdrawal compared to cocaine repeated exposure (Fig. 4B, p < 0.05).

GLAST

Two-way ANOVA did not reveal any significant difference in the expression of GLAST in the NAc between all groups during repeated cocaine exposure or cocaine withdrawal (Fig. 4 C).

GLT-1, xCT and GLAST expression in the mPFC

Two-way ANOVA did not reveal any significant difference in the mPFC in GLT-1, xCT and GLAST expression between all groups during repeated cocaine exposure or cocaine withdrawal (Table 3).

Table 3.

GLT-1, xCT and GLAST expression in the mPFC at two different time points (after 7 days of repeated cocaine exposure and after 5 days of cocaine withdrawal). Date are expressed as mean ± SEM. (n=5 for each group).

| Group | GLT-1 | xCT | GLAST | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water control group | Ethanol-Naive | 100 ± 0.00 | 100 ± 0.00 | 100 ± 0.00 |

| Repeated Cocaine exposure | Ethanol-Saline | 107.23 ± 6.75 | 86.90 ± 3.08 | 94.42 ± 3.47 |

| Ethanol-Cocaine 10 mg/kg | 101.15 ± 7.99 | 105.94 ± 7.61 | 98.40 ± 4.44 | |

| Ethanol-Cocaine 20 mg/kg | 99.03 ± 7.57 | 88.42 ± 3.87 | 114.06 ± 7.33 | |

| Cocaine withdrawal | Ethanol-Saline | 91.21 ± 4.29 | 78.19 ± 2.99 | 109.22 ± 9.25 |

| Ethanol-Cocaine 10 mg/kg | 101.34 ± 6.87 | 102.43 ± 8.11 | 109.80 ± 2.84 | |

| Ethanol-Cocaine 20 mg/kg | 93.53 ± 5.89 | 95.17 ± 8.61 | 119.52 ± 7.43 |

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined the effects of repeated cocaine exposure and withdrawal on ethanol intake, gene and protein expression of glutamate transporters in both the NAc and mPFC of male P rats. We found that voluntary ethanol consumption was significantly lower with cocaine (20 mg/kg) from Day 3 through Day 8. Since ethanol intake was significantly altered during these days, we euthanized rats at two time points (Day 7 and on withdrawal to cocaine Day 5). Alternatively, daily water intake was significantly higher with cocaine 20 mg/kg on Day 2, 3, 5, 7 and 9. This increase in water consumption might be a compensatory mechanism to maintain overall fluid balance. This robust increase in water consumption is parallel to the reduction in ethanol intake, which is in agreement with previous studies from our lab and others that observed a surge in water intake by P rats during alcohol deprivation period or after β-lactam treatment (Bell et al., 2008, Rao et al., 2015). The current ethanol drinking results differ from previously published reports showing that acute/chronic cocaine exposure increased voluntary ethanol consumption and ethanol self-administration (Ikegami et al., 2002, Knackstedt et al., 2006, Hauser et al., 2014). However, studies reported that repeated systemic injections of 50 mg/kg cocaine daily for one week decreased ethanol consumption, while repeated systemic injections of 10 mg/kg cocaine daily for one week had no effect on ethanol consumption (Uemura et al., 1998). Another study revealed that pretreated rats with six injections of 10 mg/kg cocaine, spaced by 3 –day interval, subsequently allowed access to ethanol intake in an unrestricted free-choice had no effect on ethanol consumption (Cailhol and Mormede, 2000). However, acute cocaine injection at dose of 10 mg/kg or 2.5 mg/kg has been shown an increase in ethanol consumption 2 and 6 hours post-cocaine injections (Cepko et al., 2014). The discrepancy of these results might be due to the accessibility of ethanol and the tested doses of cocaine. Most of the previous studies had limited access to ethanol while our present study had 24 hr access to ethanol during cocaine exposure. These findings are in agreement with a previous study demonstrated that continuous access to ethanol reduced the amount consumed per drinking episode compared to limited access on ethanol self-administration (Files et al., 1994). Importantly, ethanol intake was not significantly altered from Day 9 through Day 12 indicating neuroadaptations due to a repeated non- contingent cocaine exposure. These findings are in agreement with previous reports, which revealed that repeated cocaine exposure caused behavioral sensitization due to changes in glutamatergic transmission in the NAc and PFC [For review see (Vanderschuren and Kalivas, 2000)].

The voluntary ethanol intake alone or combined with repeated cocaine administration (10 or 20 mg/kg, i.p.) caused significant downregulation of both gene and protein expression of GLT-1 and xCT in the NAc. GLAST gene expression was significantly downregulated with cocaine 20 mg/kg after cocaine withdrawal in the NAc. The protein expression level of GLT-1 and xCT in cocaine-treated group was not significantly different from ethanol drinking group as compared to ethanol naïve group. These findings suggest that repeated cocaine administration during voluntary ethanol drinking had no additive effect on gene/protein expression of GLT-1 and xCT in the NAc. It is noteworthy that cocaine self-administration has been shown to downregulate protein expression of both GLT-1 and xCT in the NAc (Sari et al., 2009, Knackstedt et al., 2010a, Knackstedt et al., 2010b, Reissner et al., 2015). Similarly, voluntary ethanol drinking for five weeks also downregulated protein expression of both GLT-1 and xCT in the NAc. However, we did not find any additive effect of cocaine on ethanol-induced downregulation of GLT-1 and xCT. Nevertheless, Western blot and RT-PCR do not measure the functional activity of glutamate transporters. Further studies are needed to examine the effect of cocaine and ethanol co-exposure on the activity of glutamate transporters and glutamate level in the NAc and mPFC of P rats. There might be differences in the drug administration methods. It has been shown that contingent rather than non-contingent drug exposure has a distinct neurochemical changes in mesolimbic system (Lecca et al., 2007, Lominac et al., 2012). Findings have shown that repeated cocaine (20 mg/kg, i.p.) injections for seven consecutive days followed by a drug-free (withdrawal) period of 10 days did not affect either GLT-1 or GLAST expression level in the dorsal striatum (Parikh et al., 2014). Several studies confirmed that environmental factors and cues are important in the modulation of cocaine ability to elevate extracellular glutamate level in the NAc (Hotsenpiller et al., 2001). The voluntary ethanol intake alone or combined with repeated cocaine administration (10 or 20 mg/kg, i.p.) caused no significant downregulation of both gene and protein expression of GLT-1, xCT or GLAST in the mPFC. These findings are in agreement with previous data that showed neither ethanol nor cocaine downregulated GLT-1 in the PFC (Sari and Sreemantula, 2012, Reissner et al., 2014).

During cocaine withdrawal period, the protein expression of GLT-1 and xCT in cocaine-treated groups were not significantly different from ethanol-naïve group in the NAc and mPFC. Animals treated with cocaine (10 mg/kg, i.p.) showed a significant increase in protein/gene expression of GLT-1 and xCT compared to saline treated animals in the NAc but not mPFC. GLT-1 and xCT expression levels were increased during cocaine withdrawal compared to cocaine repeated exposure group. However, there is little known about the effects of the co-abuse of cocaine and ethanol on several target systems in the brain. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, there is less studies about the effect of co-exposure of cocaine and ethanol on the glutamatergic system. The expression level of GLAST in either cocaine or saline treated groups was not significantly different as compared to the ethanol naïve group in the NAc and mPFC during repeated cocaine exposure and withdrawal to cocaine period. Previous studies have suggested that repeated cocaine administration causes hyper-excitability state in the mPFC (Nasif et al., 2005). Glutamate release in the mPFC was increased in rats after 1 and 7 days of repeated cocaine exposure and returned to the pre-cocaine exposure level after 30 days of withdrawal (Williams and Steketee, 2004).

In conclusion, this study revealed that repeated cocaine exposure at higher dose decreased ethanol intake. Ethanol exposure decreased protein and gene expression of both GLT-1 and xCT in the NAc, but not the mPFC, regardless of cocaine co-exposure, but only after seven days of continuous cocaine exposure. However, we revealed here that only the combination of ethanol and cocaine at higher dose had an effect on GLAST gene expression at Day 5 of withdrawal of cocaine in the NAc but not mPFC. We suggest that the anatomically differential effects of co-abuse of ethanol and cocaine might be associated with complexity of neurocircuitry and drug interaction between the two drugs.

Highlight.

Cocaine 20 mg/kg decreased ethanol intake from Day 3 through Day 8.

GLT-1 relative mRNA expression decreased with ethanol and cocaine in NAc.

GLT-1 and xCT were downregulated with ethanol and cocaine co-exposure in NAc.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Jill Trendel for all her help and guidance in Real-Time quantitative PCR study.

FUNDING

The work was supported in part by Award Number R01AA019458 (YS) from the National Institutes on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and fund provided by The University of Toledo

Abbreviations

- GLT-1

glutamate transporter type 1

- xCT

cystine/glutamate transporter

- GLAST

glutamate Aspartate Transporter

- NAc

Nucleus Accumbens

- P

alcohol preferring

- mPFC

medial prefrontal cortex

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adinoff B. Neurobiologic processes in drug reward and addiction. Harvard review of psychiatry. 2004;12:305–320. doi: 10.1080/10673220490910844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhaddad H, Kim NT, Aal-Aaboda M, Althobaiti YS, Leighton J, Boddu SH, Wei Y, Sari Y. Effects of MS-153 on chronic ethanol consumption and GLT1 modulation of glutamate levels in male alcohol-preferring rats. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience. 2014;8:366. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Althobaiti YS, Alshehri FS, Almalki AH, Sari Y. Effects of Ceftriaxone on Glial Glutamate Transporters in Wistar Rats Administered Sequential Ethanol and Methamphetamine. Frontiers in neuroscience. 2016;10:427. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DA, McFarland K, Lake RW, Shen H, Tang XC, Toda S, Kalivas PW. Neuroadaptations in cystine-glutamate exchange underlie cocaine relapse. Nature neuroscience. 2003;6:743–749. doi: 10.1038/nn1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannai S, Christensen HN, Vadgama JV, Ellory JC, Englesberg E, Guidotti GG, Gazzola GC, Kilberg MS, Lajtha A, Sacktor B, et al. Amino acid transport systems. Nature. 1984;311:308. doi: 10.1038/311308b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannai S, Ishii T. Transport of cystine and cysteine and cell growth in cultured human diploid fibroblasts: effect of glutamate and homocysteate. Journal of cellular physiology. 1982;112:265–272. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041120216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RL, Rodd ZA, Lumeng L, Murphy JM, McBride WJ. The alcohol-preferring P rat and animal models of excessive alcohol drinking. Addict Biol. 2006;11:270–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2005.00029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RL, Rodd ZA, Schultz JA, Peper CL, Lumeng L, Murphy JM, McBride WJ. Effects of short deprivation and re-exposure intervals on the ethanol drinking behavior of selectively bred high alcohol-consuming rats. Alcohol. 2008;42:407–416. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2008.03.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cailhol S, Mormede P. Effects of cocaine-induced sensitization on ethanol drinking: sex and strain differences. Behavioural pharmacology. 2000;11:387–394. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200008000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cepko LC, Selva JA, Merfeld EB, Fimmel AI, Goldberg SA, Currie PJ. Ghrelin alters the stimulatory effect of cocaine on ethanol intake following mesolimbic or systemic administration. Neuropharmacology. 2014;85:224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahchour A, Hoffman A, Deitrich R, De Witte P. Effects of ethanol on extracellular amino acid levels in high-and low-alcohol sensitive rats: a microdialysis study. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2000;35:548–553. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/35.6.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danbolt NC. Glutamate uptake. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;65:1–105. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das SC, Yamamoto BK, Hristov AM, Sari Y. Ceftriaxone attenuates ethanol drinking and restores extracellular glutamate concentration through normalization of GLT-1 in nucleus accumbens of male alcohol-preferring rats. Neuropharmacology. 2015;97:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding ZM, Rodd ZA, Engleman EA, Bailey JA, Lahiri DK, McBride WJ. Alcohol drinking and deprivation alter basal extracellular glutamate concentrations and clearance in the mesolimbic system of alcohol‐preferring (P) rats. Addiction biology. 2013;18:297–306. doi: 10.1111/adb.12018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Files FJ, Lewis RS, Samson HH. Effects of continuous versus limited access to ethanol on ethanol self-administration. Alcohol. 1994;11:523–531. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(94)90079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filip M, Papla I, Nowak E, Przegalinski E. Blocking impact of clozapine on cocaine locomotor and sensitizing effects in rats. Polish journal of pharmacology. 2003;55:1125–1130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer KD, Houston AC, Rebec GV. Role of the major glutamate transporter GLT1 in nucleus accumbens core versus shell in cue-induced cocaine-seeking behavior. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2013;33:9319–9327. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3278-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox HC, Talih M, Malison R, Anderson GM, Kreek MJ, Sinha R. Frequency of recent cocaine and alcohol use affects drug craving and associated responses to stress and drug-related cues. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:880–891. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujio M, Nakagawa T, Sekiya Y, Ozawa T, Suzuki Y, Minami M, Satoh M, Kaneko S. Gene transfer of GLT‐1, a glutamate transporter, into the nucleus accumbens shell attenuates methamphetamine‐and morphine‐induced conditioned place preference in rats. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;22:2744–2754. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gass JT, Olive MF. Glutamatergic substrates of drug addiction and alcoholism. Biochemical pharmacology. 2008;75:218–265. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg SD, Martin LJ, Rothstein JD. Regional deafferentiation down‐regulates subtypes of glutamate transporter proteins. Journal of neurochemistry. 1995;65:2800–2803. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65062800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser SR, Wilden JA, Deehan GA, Jr, McBride WJ, Rodd ZA. Cocaine influences alcohol-seeking behavior and relapse drinking in alcohol-preferring (P) rats. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research. 2014;38:2678–2686. doi: 10.1111/acer.12540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotsenpiller G, Giorgetti M, Wolf ME. Alterations in behaviour and glutamate transmission following presentation of stimuli previously associated with cocaine exposure. The European journal of neuroscience. 2001;14:1843–1855. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikegami A, Olsen CM, Fleming SM, Guerra EE, Bittner MA, Wagner J, Duvauchelle CL. Intravenous ethanol/cocaine self-administration initiates high intake of intravenous ethanol alone. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. 2002;72:787–794. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)00738-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knackstedt LA, Ben-Shahar O, Ettenberg A. Alcohol consumption is preferred to water in rats pretreated with intravenous cocaine. Pharmacology, biochemistry, and behavior. 2006;85:281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knackstedt LA, LaRowe S, Mardikian P, Malcolm R, Upadhyaya H, Hedden S, Markou A, Kalivas PW. The role of cystine-glutamate exchange in nicotine dependence in rats and humans. Biological psychiatry. 2009;65:841–845. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knackstedt LA, Melendez RI, Kalivas PW. Ceftriaxone restores glutamate homeostasis and prevents relapse to cocaine seeking. Biol Psychiatry. 2010a;67:81–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knackstedt LA, Moussawi K, Lalumiere R, Schwendt M, Klugmann M, Kalivas PW. Extinction training after cocaine self-administration induces glutamatergic plasticity to inhibit cocaine seeking. The Journal of neuroscience. 2010b;30:7984–7992. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1244-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn S, Gallinat J. Common biology of craving across legal and illegal drugs - a quantitative meta-analysis of cue-reactivity brain response. The European journal of neuroscience. 2011;33:1318–1326. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecca D, Cacciapaglia F, Valentini V, Acquas E, Di Chiara G. Differential neurochemical and behavioral adaptation to cocaine after response contingent and noncontingent exposure in the rat. Psychopharmacology. 2007;191:653–667. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0496-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2− ΔΔCT method. methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lominac KD, Sacramento AD, Szumlinski KK, Kippin TE. Distinct neurochemical adaptations within the nucleus accumbens produced by a history of self-administered vs non-contingently administered intravenous methamphetamine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:707–722. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madayag A, Lobner D, Kau KS, Mantsch JR, Abdulhameed O, Hearing M, Grier MD, Baker DA. Repeated N-acetylcysteine administration alters plasticity-dependent effects of cocaine. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:13968–13976. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2808-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magura S, Rosenblum A. Modulating effect of alcohol use on cocaine use. Addictive behaviors. 2000;25:117–122. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00128-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melendez RI, Hicks MP, Cagle SS, Kalivas PW. Ethanol exposure decreases glutamate uptake in the nucleus accumbens. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:326–333. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000156086.65665.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller NS, Millman RB, Keskinen S. The diagnosis of alcohol, cocaine, and other drug dependence in an inpatient treatment population. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 1989;6:37–40. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(89)90018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasif FJ, Hu XT, White FJ. Repeated cocaine administration increases voltage-sensitive calcium currents in response to membrane depolarization in medial prefrontal cortex pyramidal neurons. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2005;25:3674–3679. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0010-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh V, Naughton SX, Shi X, Kelley LK, Yegla B, Tallarida CS, Rawls SM, Unterwald EM. Cocaine-induced neuroadaptations in the dorsal striatum: glutamate dynamics and behavioral sensitization. Neurochemistry international. 2014;75:54–65. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2014.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao PS, Goodwani S, Bell RL, Wei Y, Boddu SH, Sari Y. Effects of ampicillin, cefazolin and cefoperazone treatments on GLT-1 expressions in the mesocorticolimbic system and ethanol intake in alcohol-preferring rats. Neuroscience. 2015;295:164–174. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reissner KJ, Brown RM, Spencer S, Tran PK, Thomas CA, Kalivas PW. Chronic administration of the methylxanthine propentofylline impairs reinstatement to cocaine by a GLT-1-dependent mechanism. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:499–506. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reissner KJ, Gipson CD, Tran PK, Knackstedt LA, Scofield MD, Kalivas PW. Glutamate transporter GLT-1 mediates N-acetylcysteine inhibition of cocaine reinstatement. Addict Biol. 2015;20:316–323. doi: 10.1111/adb.12127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riga D, Matos MR, Glas A, Smit AB, Spijker S, Van den Oever MC. Optogenetic dissection of medial prefrontal cortex circuitry. Frontiers in systems neuroscience. 2014;8:230. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2014.00230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sari Y, Sakai M, Weedman JM, Rebec GV, Bell RL. Ceftriaxone, a beta-lactam antibiotic, reduces ethanol consumption in alcohol-preferring rats. Alcohol and alcoholism. 2011;46:239–246. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agr023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sari Y, Smith KD, Ali PK, Rebec GV. Upregulation of GLT1 attenuates cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2009;29:9239–9243. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1746-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sari Y, Sreemantula S. Neuroimmunophilin GPI-1046 reduces ethanol consumption in part through activation of GLT1 in alcohol-preferring rats. Neuroscience. 2012;227:327–335. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sari Y, Sreemantula SN, Lee MR, Choi D-S. Ceftriaxone treatment affects the levels of GLT1 and ENT1 as well as ethanol intake in alcohol-preferring rats. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience. 2013;51:779–787. doi: 10.1007/s12031-013-0064-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen H-w, Scofield MD, Boger H, Hensley M, Kalivas PW. Synaptic glutamate spillover due to impaired glutamate uptake mediates heroin relapse. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2014;34:5649–5657. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4564-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stromberg MF, Mackler SA. The effect of cocaine on the expression of motor activity and conditioned place preference in high and low alcohol-preferring Wistar rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2005;82:314–319. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawfik VL, Lacroix-Fralish ML, Bercury KK, Nutile-McMenemy N, Harris BT, Deleo JA. Induction of astrocyte differentiation by propentofylline increases glutamate transporter expression in vitro: heterogeneity of the quiescent phenotype. Glia. 2006;54:193–203. doi: 10.1002/glia.20365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uemura K, Li YJ, Ohbora Y, Fujimiya T, Komura S. Effects of repeated cocaine administration on alcohol consumption. Journal of studies on alcohol. 1998;59:115–118. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren LJ, Kalivas PW. Alterations in dopaminergic and glutamatergic transmission in the induction and expression of behavioral sensitization: a critical review of preclinical studies. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;151:99–120. doi: 10.1007/s002130000493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JM, Steketee JD. Cocaine increases medial prefrontal cortical glutamate overflow in cocaine-sensitized rats: a time course study. The European journal of neuroscience. 2004;20:1639–1646. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]