Abstract

A recently discovered DNA repair protein of 303 aa from the archaeal organism Ferroplasma acidarmanus was studied. This protein (AGTendoV) consists of a fusion of the C-terminal active site domain of O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase (AGT) with an endonuclease V domain. The AGTendoV recombinant protein expressed in Escherichia coli and purified to homogeneity repaired O6-methylguanine lesions in DNA via alkyl transfer action despite the complete absence of the N-terminal domain and some differences in key active site residues present in known AGTs. The AGTendoV recombinant protein also cleaved DNA substrates that contained the deaminated bases uracil, hypoxanthine, or xanthine in a similar manner to E. coli endonuclease V. Expression of AGTendoV in E. coli GWR109, a strain that lacks endogenous AGT activity, protected against both the killing and mutagenic activity of N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine and was more effective in preventing mutations than human alkyltransferase, suggesting that the endonuclease V activity may also repair a promutagenic lesion produced by this alkylating agent. Expression of AGTendoV in a DNA repair-deficient E. coli nfi-alkA- strain protected from spontaneous mutations arising in saturated cultures and restored the mutation frequency to that found in the nfi+ alkA+ strain. These results demonstrate the physiological occurrence of two completely different but functional DNA repair activities in a single polypeptide chain.

Keywords: deamination, genotoxicity, alkylation

AGT (O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase) is a DNA repair protein that removes alkyl adducts from the O6-position of guanine and O4-position of thymine in DNA (1, 2). If they are not removed, these lesions are highly mutagenic and carcinogenic (1, 3, 4). AGTs repair these DNA adducts by transferring the alkyl group onto a cysteine amino acid residue at the active site of the protein, thus restoring the DNA to its unmodified form in a single step. This alkyl transfer reaction permanently inactivates the AGT, and synthesis of new protein is required for further repair of the DNA damage. The presence of a characterized AGT gene product or a putative gene coding for the protein has been reported so far in >100 different species from the three domains of life, Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukarya. However, it is not ubiquitous: it is apparently absent from plants, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, and Deinococcus radiodurans. The AGT proteins share a highly conserved -PCHRV- amino acid sequence in their active site and contain a number of other conserved amino acids in the active site and DNA-binding domain of the protein. The widespread presence of AGT indicates the occurrence of alkylation damage to DNA under a variety of living conditions and the need to repair such damage in the cell. Alkylating agents including N-nitroso compounds are present in the environment and can be generated endogenously.

Crystal structures for AGT from three different species (Escherichia coli, human, and Pyrococcus kodakaraensis) have been determined. All exhibit a similar two-domain structure with the DNA-binding and active site pocket present in the C-terminal domain (2, 5–7). This domain contains multiple highly conserved residues, but the N-terminal domain does not and its function is unclear.

Spontaneous deamination of DNA bases such as cytosine, adenine, and guanine leads to the production of highly mutagenic lesions uracil, hypoxanthine, or xanthine, respectively (8). These lesions are also generated by intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS). A highly conserved enzyme acting on DNA containing deaminated bases was first identified by Gates and Linn (9) in Escherichia coli as the product of nfi gene and is called endonuclease V. Endonuclease V is a magnesium-dependent endonuclease that makes a nick at the second phosphodiester bond 3′ to the substrate lesion, leaving 3′-OH and 5′-P termini (10). It is suspected that a 3′–5′ exonuclease activity followed by DNA polymerase and DNA ligase activities would then complete the repair. Subsequently, endonuclease V has been identified in the archaeal, bacterial, and eukaryotic organisms (8, 11–13), and it has been found that, in addition to the ability to act on DNA containing deaminated bases, some of these proteins can act on a variety of other DNA damage sites formed by ROS that alter the secondary structure of DNA (8, 14). The importance of endonuclease V has been established by studies of nfi- mutants that lack this activity and are more sensitive to spontaneous mutations caused by endogenous nitrosating agents formed in oxygen-poor cultures (15) and mutations induced by nitrous acid (16).

The iron-oxidizing archaeon Ferroplasma acidarmanus was found in slime streamers attached to pyrite surfaces at a sulfide ore body in Iron Mountain, CA (17). It grows at a very low pH in the presence of high levels of heavy metals and has an ability to transform the sulfide found in metal ores to heavy metal-bearing sulfuric acid, the major contaminating solution draining into nearby rivers, streams, and groundwater (18). The F. acidarmanus (fer1) genome has been sequenced (GenBank accession nos. AABC03000001–AABC03000061). In the present work, we describe the characterization of a bifunctional DNA repair protein (termed AGTendoV) from F. acidarmanus. This protein has both AGT and endonuclease V activities. The AGT domain has several previously undescribed features. When expressed in E. coli, AGTendoV provides a very high level of protection from the toxic effects of the methylating agent N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG). The occurrence of two different DNA repair activities in a single polypeptide is a unique property.

Materials and Methods

Materials. All oligodeoxynucleotides, except the one containing xanthine, and Penta-His antibody were purchased from Qiagen Operon. E. coli XL1-Blue bacterial strain and Pfu polymerase enzyme were purchased from Stratagene. Restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs. Talon Metal Affinity IMAC Resin was purchased from Clontech. Ampicillin, isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG), hemocyanin, calf thymus DNA, and most other biochemical reagents were purchased from Sigma. Rapid DNA Ligation kit and urea were purchased from Roche Applied Science. Nitrocellulose filters (0.45 μm) were obtained from Millipore. O6-Benzylguanine (BG) (19) and a standard for dXao quantification (20) were prepared as described.

Synthesis of Oligonucleotides Containing Deoxyxanthosine. The deoxyxanthosine-containing oligodeoxyribonucleotide was prepared on a 10-μmol scale by using an Applied Biosystems 394 DNA/RNA synthesizer essentially as described (21), except that the 5′-O-(4,4′-dimethoxytrityl)-2,6-di-O-[2-(4-nitrophenyl)-ethyl]-2′-deoxyxanthosine was purified by silica gel column chromatography using dichloromethane/ethyl acetate/triethylamine (5:5:1) as solvent. The intermediate was converted to a 3′-O-(2-cyanoethyl)-N,N-diisopropylphosphoramidite derivative by using an in situ activation procedure (22). The deoxyxanthosine phosphoramidite was coupled for 15 min. The final 5′-O-(4,4′-dimethoxytrityl)-containing oligodeoxyribonucleotide was cleaved from the solid support by standard ammonium hydroxide treatment, and the resulting solution was heated to 55°C overnight to remove base protecting groups. The nitrophenylethyl protecting groups on the deoxyxanthosine residue were removed as described (21). The dimethoxytritylated oligodeoxyribonucleotide was purified by HPLC on a Hamilton PRP-1 column (10 μ, 205 × 10 mm) using a solvent composed of 0.1 M triethylammonium acetate pH 7.0 (buffer A) and acetonitrile (buffer B) in a linear gradient from 10% to 40% buffer B over 60 min at a flow rate of 3 ml/min (retention time, 36 min). After removal of the dimethoxytrityl group as described (22), the resulting oligodeoxyribonucleotide was purified by HPLC on the system described using a gradient of 5% to 40% buffer B over 60 min (retention time, 19.5 min). Enzymatic digestion of the oligodeoxyribonucleotide to nucleosides (22) indicated the following number of nucleoside residues/expected: dCyd, 7.4/8; dGuo, 10.7/11; dThd, 5.5/5; dAdo, 5.6/6; dXao, 1.0/1.

Construction of Plasmid pQE-FaAGTendoV for Expression of F. acidarmanus AGTendoV. Based on the reported DNA sequence of the bifunctional DNA repair protein (GenBank accession no. ZP_00307482), specific primers were synthesized and used for the amplification of AGTendoV from F. acidarmanus genomic DNA. The primers used contained restriction enzyme sites for EcoRI (sense) and BamHI (antisense), which are indicated in bold and were 5′-TCGACAGA AT TCAT TA A AGAGGAGAAATTAACTATGAATTATACACAT-3′ (sense) and 5′-TTAACCGGATCCGCTCGGCAATCTCCG-3′ (antisense) (ATG start codon underlined). The PCR was carried out by using Pfu polymerase with 50 ng of genomic DNA from F. acidarmanus (kind gift from Jill Banfield, University of California, Berkeley) as template under the following conditions: initial denaturation for 3 min at 94°C followed by 35 cycles of denaturation (at 92°C for 30 s), annealing (at 52°C for 30 s), and extension (at 72°C for 30 s) with a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The PCR product (954 bp) was digested with EcoRI and BamHI restriction enzymes and purified by electrophoresis on 0.8% agarose gel. The DNA was isolated from the gel by using Qiagen gel extraction kit and ligated into a modified pQE-30 vector (23) digested with the same enzymes to form pQE-FaAGTendoV. The entire coding region of the plasmid construct was sequenced to ensure that no secondary mutations were introduced during construction.

Protein Purification. The pQE-FaAGTendoV was transformed into E. coli XL1-B strain for protein expression and purification. The protein expressed from this plasmid contain a (His)6 tag at the C terminus (23) and it was purified by immobilized metal affinity chromatography (24). The purified protein was analyzed by SDS/PAGE and visualized by Coomassie blue staining.

AGT Activity Assay and Inhibition by BG. The AGT activity of purified AGTendoV was measured at the temperatures indicated by determining the transfer of [3H]methyl groups to the purified AGTendoV protein from O6-[3H]methylguanine in a [3H]methylated DNA substrate as described (24). The assay medium (1.0 ml) contained 25 mM sodium citrate (pH 6.6), 5 mM DTT, 50 μg of hemocyanin, 0.1 mM EDTA, 15 μg of the [3H]methylated calf thymus DNA substrate, and 35 ng of purified AGTendoV. AGT activity assay at different pH conditions was carried out in either 25 mM sodium citrate (pH 4.0, 5.0, 6.0, and 6.6) or 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.6 and 8.6). The sensitivity to BG was ascertained by incubation of 50 ng of purified AGTendoV with different concentrations of BG in 25 mM sodium citrate (pH 6.6), 50 μg of hemocyanin, 5 mM DTT, and 0.1 mM EDTA at 46°C for 30 min. The residual AGT activity was then determined as described above.

Endonuclease Activity. The endonuclease activity assay was carried out according to He et al. (25) using a substrate oligodeoxynucleotide 5′-TGCAGGTCGACT*AGGAGGATCCCCGGGTAC-3′ where * = deoxyribonucleosides containing uracil (U), hypoxanthine (H), xanthine (X), or O6-methylguanine (m6G). The reaction mixture (10 μl) contained 200 fmol of 5′-[32P]-labeled single-stranded oligonucleotide substrate or double-stranded oligonucleotide substrate and 35 ng of purified AGTendoV. The double-stranded substrate was prepared by annealing with the complementary oligonucleotide strand that contained G (for U), T (for H), or C (for X or m6G) positioned opposite the altered base. The activity assay was carried out in either 20 mM Na citrate, pH 6.6/1 mM DTT or 20 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.6/1 mM DTT buffer with or without 5 mM MgCl2 at 46°C for 15 min and stopped by the addition of 10 μl of loading buffer (71% formamide, 22 mM EDTA and 0.1% bromophenol blue). Five microliters of reaction sample was loaded onto 12.5% denaturing polyacrylamide gel and electrophoresed at 200 V for 2 h. The wet gel was then wrapped in plastic wrap and exposed to x-ray film. When activity was assayed on the substrate containing m6G, the AGTendoV was preincubated with a 16-mer AGT substrate (5′-AACAGCCATATm6GGCCC-3′) to inactivate this activity and prevent the dealkylation of the potential endonuclease substrate.

Protection of E. coli from MNNG. E. coli GWR109 cells (26) containing the pQE-30 empty vector or pQE-hAGT or pQE-FaAGTendoV were grown overnight in 1 ml of LB broth containing 50 μg/ml ampicillin and 50 μg/ml kanamycin. Two milliliters of fresh LB medium (containing 50 μg/ml ampicillin and 50 μg/ml kanamycin) was then inoculated with 20 μl of the overnight culture and grown with agitation at 200 rpm at 37°C. When the OD600 reached 0.5, the cultures were exposed to MNNG (from 0 to 6 μg/ml by addition of a 0.5 mg/ml stock solution in 100 mM Na acetate buffer, pH 5.0). After 30 min at 37°C, the cells were collected by centrifugation and then suspended in 2 ml of fresh LB medium. The bacteria were diluted and spread on LB plates containing 50 μg/ml ampicillin and 50 μg/ml kanamycin. The plates were incubated at 37°C and surviving colonies were counted 16–20 h later. The cultures were also plated on LB plates containing 100 μg/ml rifampicin, 50 μg/ml ampicillin, and 50 μg/ml kanamycin to determine forward mutation frequency. The plates were incubated at 37°C, and Rifr colonies were counted after 36–40 h. The mutation frequency of the rpoB gene in GWR109 cells was expressed as the number of rpoB mutants per 108 survivors, after adjusting to the level of surviving cells when grown on LB plates lacking rifampicin.

The level of expression of the human AGT and AGTendoV cells was probed as follows. The E. coli GWR109 cell pellets from 120-μl cultures at OD600 0.5 were lysed directly in SDS/PAGE loading buffer by heating at 100°C for 10 min. The samples were separated on SDS/15% polyacrylamide gel and transferred to poly(vinylidene difluoride) membranes, and the proteins were detected by using Penta-His antibody (Qiagen catalog no. 34660).

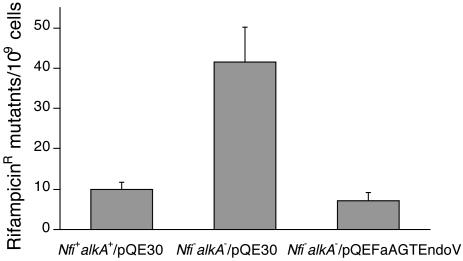

Effect of FaAGTendoV on Spontaneous Mutation Frequency. Spontaneous mutation frequencies were estimated as described by Moe et al. (11) for mouse endonuclease V in an E. coli strain deficient in endonuclease V and alkA. AlkA also removes deaminated bases in DNA (27), and it was shown by Moe et al. (11) that the double mutant nfi-alkA- exhibits significant mutator phenotype. The MG1655 wild type (nfi+ alkA+) and the endonuclease V deficient (nfi-) strains were obtained from E. coli Genome Project (University of Wisconsin, Madison). The MG1655 (nfi-) strain was deleted for alkA following the method of Datsenko and Wanner (28) to create nfi-alkA- strain. Comparisons were made between the nfi+ alkA+ transformed with pQE lacking an insert, nfi-alkA- transformed with pQE lacking an insert, and nfi-alkA- strains transformed with pQE-FaAGTendoV and the mutation frequencies were determined by means of a modified fluctuation test (11, 29). For each experiment, an appropriate dilution of the bacterial culture grown to saturation was plated on LB plates (100 μg/ml ampicillin) to estimate the number of viable cells. Undiluted original cultures (200 μl) were plated on LB plates containing rifampicin (100 μg/ml) to identify rifampicin resistant bacteria.

Results

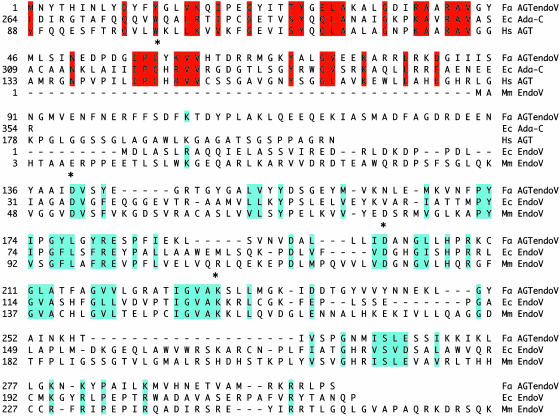

Analysis of the F. acidarmanus genome indicates the presence of a gene (GenBank accession no. ZP_00307482) that encodes a 303-aa protein. This protein (AGTendoV) contains a domain resembling AGT at its N-terminal end, and the remaining part of the protein is similar to endonuclease V (Fig. 1). The N-terminal end (residues 1–90) of AGTendoV is similar to the alkyl group acceptor site and the winged helix DNA-binding domain of known AGTs (2). Most of the amino acid residues known to be critical for AGT activity from structural and site-directed mutagenesis studies are present in the AGTendoV with the exception of the substitution of Tyr for His and Lys for Arg adjacent to the alkyl group acceptor cysteine residue (-PCYK-for -PCHR-) and the presence of Asp for Glu at position equivalent to 172 in the human AGT. The remaining 213-aa sequence of AGTendoV exhibits significant homology with E. coli endonuclease V (Fig. 1). All of the conserved amino acid residues that were shown to be essential for endonuclease V activity (11, 30, 31) are present in AGTendoV including the residues Asp-140, Asp-200, and Lys-229.

Fig. 1.

Amino acid sequence and alignment of F. acidarmanus AGTendoV. The F. acidarmanus AGTendoV sequence (Fa AGTendoV) is aligned with portions of the AGT sequences from E. coli Ada (Ec Ada-C) and human (Hs AGT) and with endonuclease V sequences from E. coli (Ec EndoV) and mouse (mouse EndoV). Key residues that are identical (or highly conservative changes) are shown in red for the AGT domain and blue for the endonuclease V domain. The active site Cys in AGT and the amino acid residues in endonuclease V that are involved in incision activity are indicated by asterisks above the amino acids.

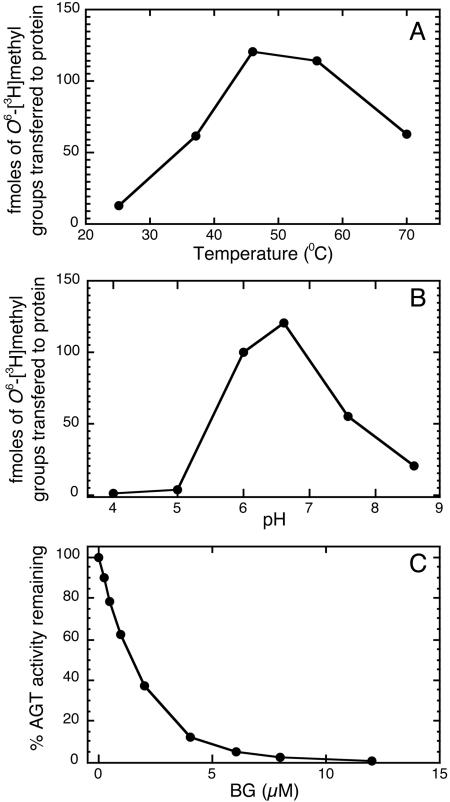

The AGTendoV protein with a C-terminal (His)6 tag was expressed in E. coli and purified by immobilized metal affinity chromatography. A single band of 35 kDa was observed on polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (results not shown). When incubated with methylated DNA containing O6-[3H]methylguanine, the AGTendoV carried out a repair AGT reaction leading to formation of [3H]-methylated protein (Fig. 2A and 2B). The reaction was pH and temperature dependent and exhibited optimal activity at pH 6.6 and 46°C. Repair of O6-methylguanine was confirmed by measuring the loss O6-[3H]methylguanine from methylated calf thymus DNA parallel to the appearance of [3H]AGTendoV. The AGTendoV did not repair O4-methylthymine in a [3H]methylated poly(dA.dT) substrate under these conditions (data not shown). The optimal temperature of 46°C is consistent with the growth of F. acidarmanus at 45°C (17). Although this organism grows in very acidic environments, its intracellular pH could be close to neutral values that were optimal for AGT activity as observed for other thermoacidophilic archaeal organisms (32, 33).

Fig. 2.

AGT assay of purified AGTendoV. (A) The effect of temperature. (B) The effect of pH. (C) The inactivation by BG.

BG is an efficient inactivator of human AGT activity (19) serving as a substrate for the alkyl transfer reaction leading to the formation of S-benzylcysteine at the active site (34). The AGT-endoV protein was also sensitive to BG with an ED50 value of ≈1.5 μM (Fig. 2C), providing additional evidence that the protein has AGT activity and is capable of accepting alkyl groups from the O6-position of guanine. The ability to react well with BG is not a universal property of AGTs; the human protein is sensitive, but E. coli Ada is not. Structural and site-directed mutational studies have shown that a requirement for reaction with BG is the presence of a Pro residue at the position equivalent to 140 in the human protein (which provides a hydrophobic surface against which the benzyl group is stacked; refs. 7 and 35) and the absence of a bulky Trp residue from the active site pocket (34–36). The sensitivity of AGTendoV to BG is consistent with this hypothesis because it contains the required Pro at position 53 and has Leu at position 73 equivalent to Trp-336 in the E. coli Ada (Fig. 1).

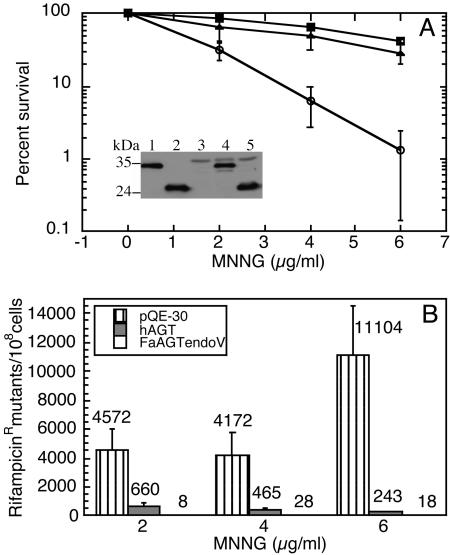

Expression of AGTendoV in E. coli strain GWR109, which does not contain endogenous AGTs, produced substantial protection from killing by MNNG compared to GWR109 cells containing a control vector plasmid (Fig. 3). The level of protection was slightly less than that obtained with cells expressing human AGT from the same vector. The presence of AGTendoV also resulted in a large reduction in the number of rifampicin resistant (Rifr) mutants that were produced on exposure to MNNG (Fig. 3). Remarkably, there was a greater reduction in Rifr mutants in cells expressing AGTendoV than those expressing human AGT. This result cannot be explained by a higher expression level of the AGTendoV. Western blotting and comparison to standards of the purified proteins showed that the amount of AGTendoV was actually slightly less (≈55%) than that of the human AGT in the GWR109 cells (Fig. 3), which is consistent with the slight reduction in protection from killing.

Fig. 3.

Protection of cells from killing and mutagenic effects of MNNG by AGTendoV. GWR 109 cells with no AGT (empty vector; circles) or expressing either AGTendoV (triangles) or human AGT (squares) were treated with MNNG, and survival was determined (A). (A Inset) The level of expression of the human AGT and AGTendoV determined by Western blotting using Penta-His antibody, which is specific for a (His)5 epitope. Purified AGTendoV (50 ng) was loaded in lane 1 and purified hAGT (50 ng) was loaded in lane 2 as controls. Lanes 3–5 show extracts from GWR109/pQE-30 cells, GWR109/pQE-Fa AGTendoV cells and GWR109/pQE-hAGT cells, respectively. (B) The occurrence of Rifr mutants. The values are shown above each bar. (Bars for cells expressing AGTendoV are too small to show up well above the x axis.) In the absence of MNNG, there were fewer than five mutants per 108 cells. Results are means ± SD for three separate experiments.

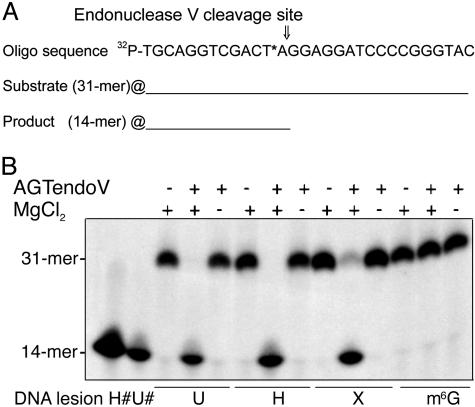

The recombinant AGTendoV exhibited efficient Mg2+-dependent strand nicking activity on double-stranded DNA substrates that contained deaminated bases hypoxanthine and xanthine at pH 7.6 (Fig. 4) and pH 6.6 (data not shown). DNA containing uracil was a good substrate at pH 7.6 (Fig. 4), but little reaction occurred at pH 6.6 (data not shown). The AGTendoV also exhibited weak activity on these lesions in single stranded substrates (results not shown). No cleavage was observed on substrates containing an O6-methylguanine lesion. The product of cleavage was a 14-mer, indicating that the position of cleavage of all of the 31-mer substrates that were attacked was at the second phosphodiester bond 3′ to the deaminated residue because the lesion was located at position 13. These results indicate that the protein does have typical endonuclease V activity toward products of deamination. Inactivation of the AGT domain by preincubation of AGTendoV with a 16-mer oligo containing a single O6-methylguanine adduct to form S-methlycysteine at Cys-58 did not alter the endonuclease V activity of AGTendoV (data not shown), demonstrating that the two DNA repair activities function independent of each other. AGTendoV also showed endonuclease V activity when expressed in a nfi-alkA- E. coli strain. As reported (11), this strain showed an increase in spontaneous mutations occurring in saturated cultures. This 4-fold increase was abolished by the expression of AGTendoV in these nfi-alkA- cells (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Endonuclease V activity of AGTendoV. (A) Substrate oligonucleotide sequence (asterisk indicates uracil, hypoxanthine, or xanthine) and predicted reaction products. (B) Activity was assessed on double-stranded oligonucleotide substrates containing uracil (U), hypoxanthine (H), xanthine (X), or O6-methylguanine (m6G) at pH 7.6. The purified AGTendoV was incubated with 5′ end 32P-labeled double stranded-oligonucleotide at 46°C for 15 min in 20 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.6) 1 mM DTT, and 5 mM MgCl2 buffer. The reaction products were separated on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel as described in Materials and Methods. Single-stranded oligonucleotides of the predicted reaction product (14-mers) containing U or H were also loaded on the gel as markers.

Fig. 5.

Suppression of spontaneous mutations in endonuclease V-deficient E. coli strain by FaAGTendoV protein. The E. coli MG1655 wild-type (nfi+alkA+), DNA repair-deficient (nfi-alkA-), and nfi-alkA- deficient cells transformed with pQE-FaAGTendoV plasmid were plated in the presence and absence of 100 μg/ml rifampicin. These results were obtained from four independent experiments and are shown as the mean ± SD.

Discussion

Our results show clearly that the F. acidarmanus AGTendoV carries out two quite distinct DNA repair reactions both in vitro and in vivo. This is the first report of a protein with combined AGT and endonuclease V activities but genes appearing to encode a similar bifunctional protein are present in three other archaeal organisms Thermoplasma acidophilum, Thermoplasma volcanium, and Picrophilus torridus. The combined AGTendoV is the only endonuclease V in F. acidarmanus and these organisms. However, F. acidarmanus also contains another gene for an AGT (accession no. ZP_00306265; 173 aa), whereas the other Archaea do not. Several bacteria, including E. coli, and the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans are known to express two AGT proteins (24, 37), but F. acidarmanus is the first archaeal organism known with this characteristic.

Although we have previously identified an AGT termed cAGT-2 from C. elegans that has a sequence resembling histone 1C fused to the carboxyl end (24), and the E. coli Ada protein contains a transcription activator domain that responds to alkylation damage fused to the O6-alkylguanine-DNA AGT domain in the C-terminal half of the protein (38), the occurrence of two distinct DNA repair activities in AGTendoV appears to be a unique property. Recently, a chimeric protein was constructed by a fusion of full-length human AGT with yeast AP endonuclease (39). This construct was designed to improve the resistance of normal cells to therapeutic alkylating agents, and it was found that it was more effective in such protection in cells treated with methylating or chloroethylating agents than AGT alone. The AGTendoV fusion would also be of interest for evaluation in this context.

Apart from its fusion to the endonuclease V domain, the AGT of F. acidarmanus AGTendoV has several unique properties. First, virtually all known AGTs have a two-domain structure. Based on the three known crystal structures, the C-terminal domain contains the active site and DNA binding motif (2, 5–7). The N-terminal domains have no amino acid sequence homology but appear quite similar in overall structure and have been postulated to be essential for stability and proper orientation of the C-terminal domain. The F. acidarmanus AGTendoV completely lacks this structural domain. It is possible that the endonuclease V domain formed by the C-terminal region provides the needed stability and orientation.

Second, virtually all known AGTs contain the sequence -PCHR- at the active site, and a highly plausible mechanism for the activation of the cysteine acceptor residue is provided by its participation in a hydrogen bonding network involving a charge relay between Glu-172, His-146, a bound water, and Cys-145 (numbered according to the residues in human AGT) (7, 40). The His residue is a critical component of this change. However, in the AGTendoV protein, it is replaced by a Tyr residue in the sequence -PCYK- suggesting that this reaction mechanism may need further study. Two other notable but conservative changes are the presence of Lys for Arg-147 and of Asp for Glu-172. Arg-147 interacts with the carboxylate of Glu-172 in human AGT, and the paired substitution may allow this interaction to be maintained in AGTendoV.

The major lesion produced by MNNG that leads to a loss of cell survival is O6-methylguanine. The greatly improved survival in the E. coli GWR109 when AGTendoV was expressed is therefore consistent with the efficient repair of this adduct by its AGT domain. Similarly, O6-methylguanine is the major mutagenic lesion formed by MNNG and its repair must be a major factor in the reduction of mutations in the rpoB gene brought about by AGTendoV. However, although AGTendoV and human AGT were effective in improving survival to MNNG, and both produced a large decrease in the number of Rifr mutants, the reduction in mutations was significantly greater when AGTendoV was present. This may be due to the ability of the endonuclease V activity to act on a lesion produced by MNNG but at present we cannot identify this lesion. Direct endonuclease V repair of O6-methylguanine could not be demonstrated using 31-mer substrates.

Previously characterized endonuclease V proteins all act on DNA containing deoxyinosine, but show differences in specificity for other substrates. The E. coli endonuclease V, which is the most extensively studied enzyme so far, was the only enzyme that clearly acts on DNA containing all of the four deamination products (uracil, hypoxanthine, oxanine, and xanthine) as well as a variety of other adducts including tetrahydrofuran, urea residues, base mismatches, AP sites, as well as loops, hairpins, pseudoY, and flap structures (8, 41). Endonuclease V proteins from mouse (11), Archaeoglobus fulgidus (12), and Thermotoga maritima (13) have now been characterized and may have a more limited substrate range with a strong preference for hypoxanthine. Our results suggest that the F. acidarmanus AGTendoV may be closely related to the E. coli protein because xanthine was a good substrate. The ability to efficiently repair alkylation and deamination products produced by reactive oxygen species may be critical for this organism to survive DNA damage during sulfide oxidation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute Grants CA-18137, CA-71976, and CA-97209.

Author contributions: S.K. and A.E.P. designed research; S.K. performed research; G.T.P. and R.C.M. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; and S.K. and A.E.P. wrote the paper.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: ATG, O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase; MNNG, N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine; BG, O6-benzylguanine.

References

- 1.Margison, G. P. & Santibáñez-Koref, M. F. (2002) BioEssays 24, 255-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daniels, D. S., Woo, T. T., Luu, K. X., Noll, D. M., Clarke, N. D., Pegg, A. E. & Tainer, J. A. (2004) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11, 714-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singer, B. & Essigmann, J. M. (1991) Carcinogenesis 12, 949-955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pauly, G. T. & Moschel, R. C. (2001) Chem. Res. Toxicol. 14, 894-900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore, M. H., Gulbus, J. M., Dodson, E. J., Demple, B. & Moody, P. C. E. (1994) EMBO J. 13, 1495-1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hashimoto, H., Inoue, T., Nishioka, M., Fujiwara, S., Takagi, M., Imanaka, T. & Kai, Y. (1999) J. Mol. Biol. 292, 707-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daniels, D. S., Mol, C. D., Arvai, A. S., Kanugula, S., Pegg, A. E. & Tainer, J. A. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 1719-1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kow, Y. W. (2002) Free Radical Biol. Med. 33, 886-893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gates, F. T. & Linn, S. (1977) J. Biol. Chem. 252, 1647-1653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demple, B. & Linn, S. (1982) J. Biol. Chem. 257, 2848-2855. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moe, A., Ringvoll, J., Nordstrand, L. M., Eide, L., Bjoras, M., Seeberg, E., Rognes, T. & Klungland, A. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3893-3900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu, J., He, B., Qing, H. & Kow, Y. W. (2000) Mutat Res. 461, 169-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang, J., Lu, J., Barany, F. & Cao, W. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 8738-8748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hitchcock, T. M., Gao, H. & Cao, W. (2004) Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 4071-4080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weiss, B. (2001) Mutat. Res. 461, 301-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weiss, B. (1999) Mutat. Res. 435, 245-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edwards, K. J., Bond, P. L., Gihring, T. M. & Banfield, J. F. (2000) Science 287, 1796-1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bond, P. L., Smriga, S. P. & Banfield, J. F. (2000) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 3842-38849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dolan, M. E., Moschel, R. C. & Pegg, A. E. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 5368-5372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moschel, R. C. & Keefer, L. K. (1989) Tetrahedron Lett. 30, 1467-1468. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wuenschell, G. E., O'Connor, T. R. & Termini, J. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 3608-3616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pauly, G. T., Powers, M., Pei, G. K. & Moschel, R. C. (1988) Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1, 391-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu, L., Xu-Welliver, M., Kanugula, S. & Pegg, A. E. (2002) Cancer Res. 62, 3037-3043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanugula, S. & Pegg, A. E. (2001) Environ. Mol. Mutagenesis 38, 235-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He, B., Qing, H. & Kow, Y. W. (2000) Mutat. Res. 459, 109-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rebeck, G. W. & Samson, L. (1991) J. Bacteriol. 173, 2068-2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Brien, P. J. & Ellenberger, T. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 26876-26884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Datsenko, K. A. & Wanner, B. L. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoess, R. H. & Herman, R. K. (1975) J. Bacteriol. 122, 474-484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aravind, L., Walker, D. R. & Koonin, E. V. (1999) Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 1223-1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang, J., Lu, J., Barany, F. & Cao, W. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 8342-8350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van de Vossenberg, J. L., Driessen, A. J., Zillig, W. & Konings, W. N. (1998) Extremophiles 2, 67-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.She, Q., Singh, R. K., Confalonieri, F., Zivanovic, Y., Allard, G., Awayez, M. J., Chan-Weiher, C. C., Clausen, I. G., Curtis, B. A., De Moors, A., et al. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 7835-7840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pegg, A. E., Boosalis, M., Samson, L., Moschel, R. C., Byers, T. L., Swenn, K. & Dolan, M. E. (1993) Biochemistry 32, 11998-12006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wibley, J. E. A., Pegg, A. E. & Moody, P. C. E. (2000) Nucleic Acid Res. 28, 393-401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crone, T. M., Kanugula, S. & Pegg, A. E. (1995) Carcinogenesis 16, 1687-1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Samson, L. (1992) Mol. Microbiol. 6, 825-831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lindahl, T., Sedgwick, B., Sekiguchi, M. & Nakabeppu, Y. (1988) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 57, 133-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roth, T. J., Xu, Y., Luo, M. & Kelley, M. R. (2003) Cancer Gene Ther. 10, 603-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guengerich, F. P., Fang, Q., Liu, L., Hachey, D. L. & Pegg, A. E. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 10965-10970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hitchcock, T. M., Dong, L., Connor, E. E., Meira, L. B., Samson, L. D., Wyatt, M. D. & Cao, W. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 38177-38183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]