Abstract

Implementation of major organizational change initiatives presents a challenge for long-term care leadership. Implementation of the INTERACT™ (Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers) quality improvement program, designed to improve the management of acute changes in condition and reduce unnecessary Emergency Department (ED) visits and hospitalizations of nursing home residents, serves as an example to illustrate the facilitators and barriers to major change in long-term care.

As part of a larger study of the impact of INTERACT™ on rates of ED visits and hospitalizations, staff of 71 nursing homes were called monthly to follow-up on their progress and discuss successful facilitating strategies and any challenges and barriers they encountered over the year-long implementation period. Themes related to barriers and facilitators were identified.

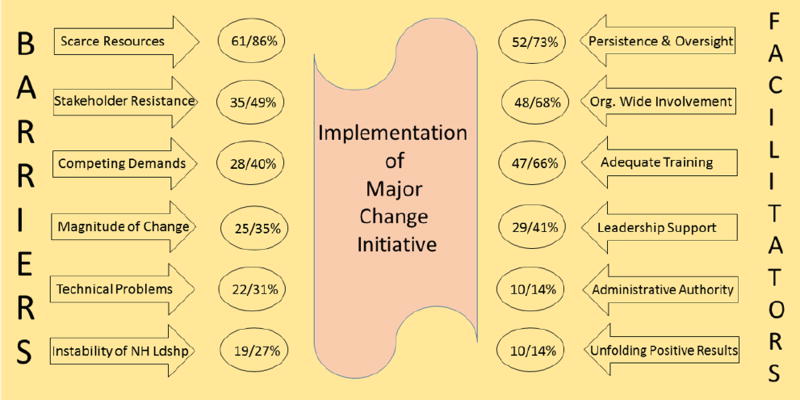

Six major barriers to implementation were identified: the magnitude and complexity of the change (35%), instability of facility leadership (27%), competing demands (40%), stakeholder resistance (49%), scarce resources (86%), and technical problems (31%). Six facilitating strategies were also reported: organization-wide involvement (68%), leadership support (41%), use of administrative authority (14%), adequate training (66%), persistence and oversight on the part of the champion (73%), and unfolding positive results (14%).

Successful introduction of a complex change such as the INTERACT™ QI program in a long-term care facility requires attention to the facilitators and barriers identified in this report from those at the frontline.

Keywords: organizational change, long-term care, nursing homes, INTERACT™

Introduction

There are approximately 15,700 nursing homes (NHs) providing care to 1,383,700 people in the United States.1 Serving these individuals is a major undertaking given the increasingly high levels of acuity and complexity of care currently provided in NHs. As resident acuity levels continue to rise due to shorter hospital stays and advanced medical interventions, providers are challenged to seek better ways to serve resident needs while offering them a homelike environment. In this article we discuss the barriers and facilitators of change reported by representatives of 71 NHs who undertook organizational change to implement the Interventions To Reduce Acute Care Transfers (INTERACT™) quality improvement program (https://interact.fau.edu). The INTERACT™ quality improvement program is designed to reduce unnecessary resident hospitalizations, an important goal given evolving changes in Medicare reimbursement and increasing penalties for excessive 30-day hospital readmissions related to certain diagnoses.2

Challenging Operating Environment

Zinn, Brannon, and Mor described NHs as “complex systems, rationally structured to produce services and other types of benefits ranging from medical care management to a homelike atmosphere offering residents choice and stimulation”.3(p.38) In addition to satisfying the needs and expectations of the residents, NHs must address the requirements of multiple stakeholders while operating within a difficult environment that is impacted by a number of factors over which they have little or no control. This stakeholder group includes local, state and federal local government (source of the penalties); families of residents, vendors, and facility employees, to name a few. Political, legal, regulatory, social, technological and economic factors are thought to affect the success of change initiatives in the NH environment.4

Political

Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements are the largest sources of revenue for government licensed and certified long-term care facilities.5 In an evolving political climate whose rules may be driven by varying political ideologies, NHs may encounter radical change to these and other reimbursement systems. For example, significant changes in the Affordable Care Act of 2010 could have major unpredictable effects on the NH industry.6

Legal/Regulatory

As one of the most regulated industries in the United States, second only to nuclear energy, members of the long-term care industry must constantly reexamine their operations in order to comply with continually changing federal, state and local laws, frequently necessitating redirection of internal and external resources.7

Social

The long-term care industry is also highly dependent on the quality of the human contact that occurs between staff and residents. The implications for leadership, governance, staff and the residents of the facility are significant. Defining, evaluating, and measuring quality in a long-term care setting is a difficult and convoluted task; understanding the social effects of leadership on staff-resident-family interactions is even more challenging.8

Technological

Increased governmental and operational pressures to install more sophisticated technology such as Electronic Health Record (EHR) systems have recently imposed enormous cost, time, and human resource demand on long term care facilities.9

Economic

Although government regulations have escalated requirements to provide higher quality care, the increased cost of this care has not been fully compensated and the economic effects can be devastating. If Medicare and/or Medicaid reimbursements were reduced, for example, the negative financial impact on the NH could be quite substantial.6 All of the previously mentioned factors have a significant impact on the solvency of a long-term care facility.

Impact of Unnecessary Hospital Transfers

The economic and iatrogenic costs of unnecessary hospital transfers are well-documented.10,11,12 Unnecessary hospitalizations of NH residents have been shown to increase health care costs and contribute to various negative patient outcomes.2 One solution is to introduce new programs that can assist staff in rapidly identifying and managing acute changes in the condition of NH residents and respecting advance care directives. INTERACT™ is an evidence-based quality improvement program that offers strategies for improving the identification, evaluation, communication, documentation, and management of acute changes in condition of NH residents and for improving advance care planning. Effective implementation has been associated with substantial reductions in hospitalizations of NH residents.13

Change Model

Successful implementation of a major organizational change initiative such as the INTERACT™ quality improvement program requires organizational commitment and management acumen. The first step in implementing any major change within an organization is to identify and evaluate the organizational units that will be affected by the change for the purpose of understanding the specific strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats to success of the planned change. Lewin was one of the first to study the concept of organizational change.14 His force field analysis (unfreeze, change, refreeze) theory provides a framework for understanding the forces that assist change (driving forces) or those that block change (restraining forces). His theory has been subject to some criticism regarding the assumption that organizations operate in a stable state.15 Despite this caveat, the basics of his theory are applicable to effecting change in long-term care facilities today.

To effect successful change, NH leaders must recognize both the driving and restraining forces that may help or hinder the change initiative and develop a plan that address them. A particularly important factor that may be either a barrier or facilitator of organizational change is its culture, defined as “both a dynamic phenomenon that surrounds us at all times, being constantly enacted and created by our interactions with others and shaped by leadership behavior, and a set of structures, routines, rules and norms that guide and constrain behavior”.16(p.1) A culture change involves a reframing of norms and expectations within the organization.17 Several studies have demonstrated the importance of changing the culture of an organization when implementing a new initiative.18,19,20 This may include changing the philosophy of care thereby transforming an impersonal institution into a safe, caring community21 or improving the quality of resident care.19 In this paper we examine the barriers and facilitators to implementing the INTERACT™ program, many of which involved culture change, reported by representatives of 71 NHs randomized to the intervention group of a clinical trial of the INTERACT™ program.

Method

A qualitative study of the barriers and facilitators to implementation of INTERACT™ reported by representatives of participating NHs was conducted during a randomized, clinical trial of INTERACT™ involving 264 NHs. Of these 264 NHs, 88 were randomly assigned to the 12-month intervention phase during which the qualitative data were collected and 71 NHs actively participated in the intervention. The results are based upon their reports.

Recruitment and Enrollment of Nursing Homes

Both profit and not-for-profit NHs were recruited for the parent project via contacts through national organizations and corporations that had previously expressed an interest in participating. Six hundred thirteen (613) interested NHs were screened for eligibility via online and telephone surveys. Criteria for participation were 1) evidence of support from corporate and facility leadership including the facility administrator, director of nursing, and medical director 2) ability to manage acute changes in condition safely within the facility as determined by availability of lab, pharmacy, and medical care resources, and 3) availability of technical support to conduct online staff training and report data electronically. NHs were excluded if they were 1) a hospital-based facility; 2) participating in another project designed specifically to reduce acute care transfers or hospitalization rates which might contaminate the intervention or control conditions; or 3) conducting more than one other major quality improvement or research project during the project period. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Florida Atlantic University.

The 264 NHs that fulfilled the above criteria were randomized into three groups with 88 NHs in each group. Group 1 was the intervention group, implementing the full INTERACT™ quality improvement program from April 2013 to March 2014. Seventy-one of the 88 NHs in this group completed the intervention. Group 2 was a comparison group asked to report any independent activities related to reducing unnecessary hospitalizations on a quarterly basis. Group 3 was also a no-treatment comparison group but did not report quarterly. NHs in Groups 2 and 3 were offered training in the implementation of the INTERACT™ quality improvement program at the end of the 12-month intervention period.

Intervention

The NHs in Group 1 were asked to select interested, experienced individuals as project champions and co-champions. The project champions and co-champions were responsible for staff training and for leading the implementation of INTERACT™ in their facilities.

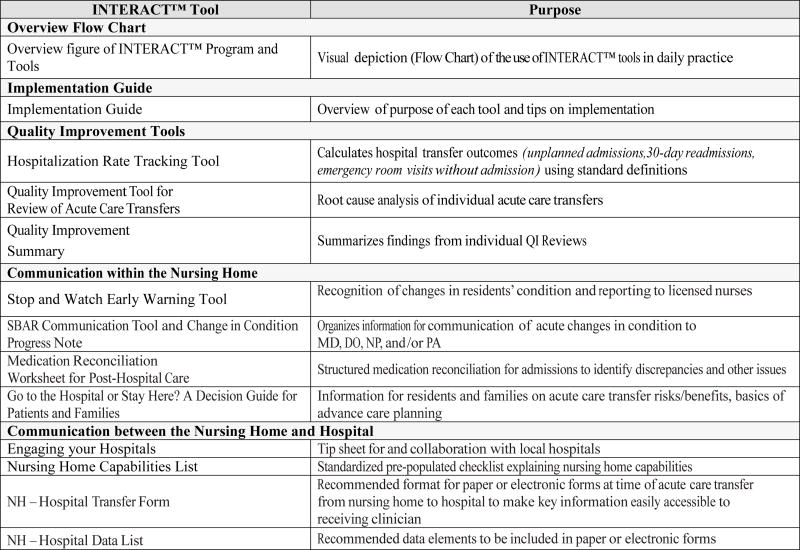

The INTERACT™ quality improvement program includes 11 resident assessment and communication tools as well as 8 resource guides and four tools for key aspects of quality improvement, including measurement of key outcomes and root-cause analyses (Figure 1). Participating facilities were provided with a one-year supply of the INTERACT™ tools as well as access to online tools and data entry portals.

Figure 1.

INTERACT™ Program Tools

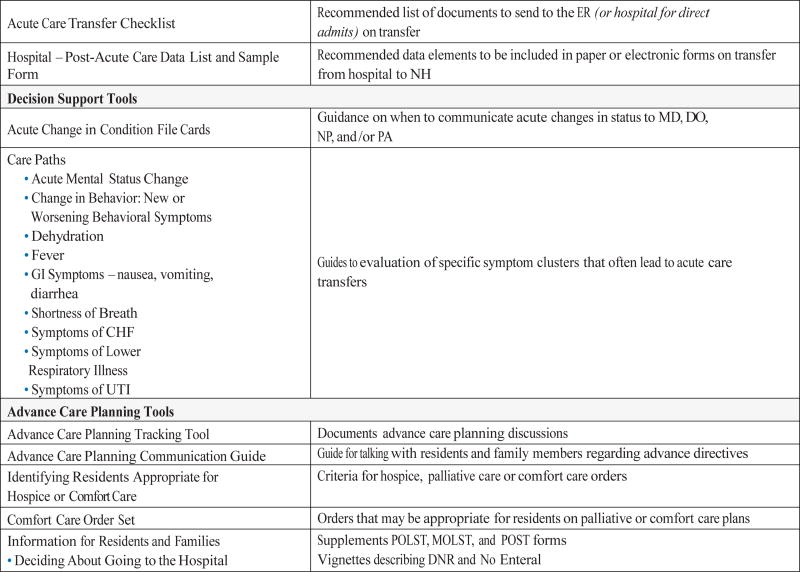

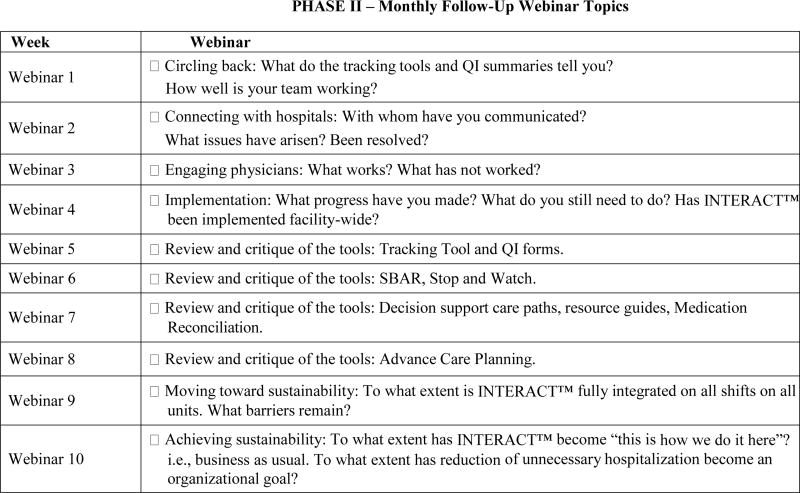

Each of the facilities in Group 1 (intervention) was required to take part in a two-phase webinar training program designed to offer organizational personnel the opportunity to learn about the multi-faceted operational aspects of the INTERACT™ program. This training was conducted by INTERACT™ team members and consisted of twenty 45-minute interactive webinars that reviewed the use of each tool and offered attendees the opportunity to ask questions and clarify any information they deemed important. Several webinars included time to discuss the various barriers encountered, effective training strategies and case studies presented by participating facilities. Phase one was an intensive 10-week training program and phase two consisted of monthly follow up webinars. Webinar topics are summarized in Figure 2. In addition to the education provided, participating NHs received regular communications by email, and had email and telephone access to project coordinators for technical support throughout the 12-month implementation period.

Figure 2.

Information Provided to Participating NHs via Webinar

Data collection

The INTERACT™ evaluation protocol included monthly telephone calls with the champion, co-champion and/or other NH leadership over the year-long implementation of INTERACT™. The calls were made to identify needs for additional assistance (e.g. difficulty accessing online training modules), answer questions, obtain information regarding any adverse events that might have occurred related to implementation, and to obtain information regarding degree of implementation of the INTERACT™ program. At each telephone call the NHs were asked, “What barriers and challenges are you facing in INTERACT™ implementation and how are you handling them?” and “Please give us examples of any strategies you found to be successful.” Answers were recorded and entered into a database by the research team member making the call.

Data Analysis

The analytic approach described by Miles, Huberman and Saldaña guided data analysis. Their approach includes data reduction (abstracting, categorizing, coding), data display (assembling, organizing, creating matrices or charts), and drawing and verifying conclusions (interpreting, explaining, reviewing) done iteratively.22

A doctoral level research associate (ZR) with prior clinical administrative experience read the responses and classified them as facilitators or barriers. Separate codes were organized into larger categories suggesting themes. The categories and themes related to identified barriers and facilitators were reviewed by the team. A final synthesis of overarching themes was then generated. Illustrative quotes and examples were added to provide for understanding and contextual richness. The frequency and percent of NHs reporting items within each barrier and facilitator were calculated and a chart of the results created by the second author (DW).

Findings

Of the 88 NHs randomized to the INTERACT™ intervention group, 17 dropped out either before implementation began or early in the course of the project, leaving 71 NHs actively participating in the year-long implementation which included responding to the monthly follow-up calls. In total, 475 (mean 7, range 4–12) telephone calls were conducted with the program champion or other representative of each NH during the 12-month study period. In 90% of the completed calls, the champion was present either alone or with the co-champion and/or the NH administrator. Ten percent of the calls were completed by the co-champion and /or an administrator.

Barriers

The magnitude and complexity of this change, leadership instability, competing demands, resistance of one or more groups of stakeholders, scarce resources and various technical problems were the major barriers identified by respondents from the 71 NHs (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Frequency and Percent of Nursing Homes Reporting Identified Barriers and Facilitators to Implementing the INTERACT™ Quality Improvement Program

Magnitude and Complexity of the Change

As indicated earlier, INTERACT™ is a complex program employing multiple tools and for most NHs requiring a change in thinking about preventability of a certain proportion of hospital transfers. Full, effective implementation requires an extended effort. As one respondent noted, “culture change takes time”. Given the resources needed to implement such a major change champions observed that it is difficult to tackle other major initiatives, such as introduction of an electronic health record, at the same time.

Leadership Instability

We opened our calls with a general question, “How have you been doing since our last call?” If any change in NH leadership had occurred, this was likely to be the first item mentioned by the champion. The changes most often mentioned were a change in the administrator, the director of nursing or the champion. In most instances, respondents noted that this change in leadership either slowed or entirely stopped implementation until stability of the leadership team was restored.

Competing Demands

The demands of additional major change initiatives occurring at the same time were reported to have made implementation difficult. Two competing demands most frequently mentioned were upcoming state surveys and implementation of an electronic health record.

Resistance to Change

Resistance came from many directions and a variety of stakeholders. Some champions reported having to “push” staff to use the new tools. One of them noted, “The champion is leading the change, but if she is not there, the unit managers are not interested in this process.” Some medical providers continued to be concerned about liability issues, others lacked confidence in the staff nurses’ evaluations of acute changes in condition (the INTERACT™ SBAR tool is designed to overcome this particular barrier). It was also reported that some of the families still believed that NHs could provide only very limited levels of care, fueling their insistence on hospital transfer if a change in the resident’s condition occurred.

Scarce Resources

Scarce resources were often cited as significant barriers to implementation. Turnover of nursing staff necessitated repeating INTERACT™ training. The champion’s own workload was sometimes a concern. One remarked, “I am doing too many jobs at once.” Another did not have a staff development person making it “very challenging for us to get our regular work done PLUS all of the required training.” An increase in acutely ill residents was also mentioned by several respondents.

Technical Problems

A great variety of technical problems were mentioned. Access to online INTERACT™ training was difficult when computer resources were limited or out-of-date. Some of the champions had to use their own personal computers to complete their online training. Entering data into the INTERACT™ online hospitalization rate tracker was difficult for many of the champions, although eventually most were able to master it. Technical assistance from members of the research team helped many champions overcome barriers. For staff of some NHs, completing one of the core tools, the SBAR communication tool, amounted to double entry of the information, a problem that would be resolved when INTERACT™ was integrated into their electronic health record.

Facilitators

The champions reported a number of facilitators as well. These included organization-wide involvement of all stakeholders, leadership support, the use of administrative authority to launch the initiative, adequate training and re-training of staff, persistence and frequent monitoring by the champions and the unfolding positive results that were eventually observed.

Organization-Wide Involvement

Most champions noted that it was essential to get all stakeholders involved and supportive of the implementation of INTERACT™. Some appointed “mini-champions” for each care unit. Some NHs made the Stop and Watch tool (a simple tool for reporting early changes in condition by CNAs and others) available to family members who appreciated having a formalized mechanism for communicating with staff. Other NHs created small work groups to function as task forces charged with implementation of INTERACT™. Having medical providers “on board” was another essential element in reducing unnecessary hospitalizations. Social workers were involved in several aspects of INTERACT™ including advance care planning. Working cooperatively with feeder hospitals and other external providers was essential but sometimes challenging, “Many times when we send patients to dialysis, they almost automatically transfer them directly to the hospital,” notes one champion, “without consulting with NH staff or the medical provider.”

Leadership Support

The champions made it clear that support from NH leadership was essential to their success for several reasons: freeing up the champion’s time to work on INTERACT™, allowing staff time for training and for the inevitably slow completion of various tools at first, including use of INTERACT™ tools in staff evaluations, and making it clear that the organization was behind the champion’s efforts.

Use of Authority

“Just tell staff they have to do it,” counseled one champion. While the use of authority is insufficient on its own, it is important for corporate leadership (if applicable) and NH administrators to make clear that this change was necessary and to introduce INTERACT™ to unit leadership.

Adequate Training

When introducing a complex program such as INTERACT™, it is essential to prepare staff thoroughly and to continue to prepare new staff when they begin their employment. Many NHs added an introduction to INTERACT™ to their new employee orientation. To provide a higher level of care than had been previously done required additional training of existing staff as well. One NH, for example, trained their nurses to administer peripheral IVs to prevent hospitalizations that had been identified as due to the resident’s need for intravenous fluids.

Persistence and Frequent Monitoring

Champions often remarked that they had to continually work to change the mindset of the staff (the essence of culture change). One recommended a “Slow and steady approach, not an ‘all at once’” approach. Another champion conducted daily audits “to make sure the process is followed.” It was evident that their leadership was the key to successful implementation. Most appointed a co-champion as well to assist with the training, re-training, one-on-one mentoring and consistent monitoring of implementation progress.

Unfolding Positive Results

Positive results were not immediately apparent but when they did emerge, they reinforced the message and increased motivation to persist with implementation. Tracking a decline in their 30-day readmission rates was especially motivating for some NHs. One champion reported receiving a letter from one of their feeder hospitals congratulating them on their success in reducing readmission rates by more than 15%. Others noted increased staff stability and resident satisfaction. Still others reported that implementing INTERACT™ helped them improve many aspects of care to the extent that some were congratulated by their surveyors and that their hospital readmission rates had dipped below the national average, all good reasons to make the recommended changes.

Frequencies and Percents

The number and percent of NHs reporting which of these barriers and facilitators of change may be found in Figure 3. Scarce resources (86%), stakeholder resistance (49%) and competing demands (40%) were the most frequently mentioned barriers. The persistence and monitoring done by the champions (73%), organization-wide involvement (68%) and adequate training of staff (66%) were the most frequently mentioned facilitators of change.

Discussion

These facilitators and barriers to implementation of a major organizational change in long term care facilities were identified by individuals on the front line, the champions and co-champions tasked with implementing the INTERACT™ quality improvement program. They emerged from the reports of these individuals when contacted by telephone periodically over the 12 months of implementation and provide us with a realistic picture of the challenges of implementing a major change in a difficult environment. Their experiences provide valuable insight and concrete guidance to those tasked with implementing a major change initiative in a long-term care institution in the future.

It is notable that study respondents did not refer to the external forces that impact NH operations, i.e. the political, legal, regulatory, social and technological forces that impinge upon every organization and its everyday functioning.6 Instead, their perspective was primarily internal to the organization, that is, what they observed and experienced directly within the facility as they implemented the INTERACT™ quality improvement program. It is likely that the outside forces were considered a “given” so little attention was paid to their influence on the desired change.

The importance of the two basic principles of culture change are evident in the reports from the facility champions. It was clear that the facility leaders’ support was essential to the successful launch of this major change initiative. Secondly, in most facilities, the implementation of the INTERACT™ quality improvement program necessitated establishment of new norms and expectations regarding rapid identification of – and response to – changes in resident condition, consideration of whether the additional care could be provided in the NH, addressing resident and family concerns about this change in condition, consideration of resident prognosis and attention to preferences indicated in advance care documents. For some facilities, this only required a modification in their approach but for others it required massive reorientation of their responses to changes in resident condition, in other words, a major culture change.

Resources

Despite the screening process, some facilities that had undertaken too many other change initiatives were included in the study and found that they could not fully concentrate their efforts on INTERACT™ implementation. Similarly, those who had limited resources struggled to find the time to learn the program and put it into practice. If they were not able to commit resources to the implementation of INTERACT™, they were likely to fail despite a well-intentioned attempt to adopt it.

Turnover

Successful change initiatives require consistency in staff, leadership and governance. In 2010, NH Administrator and Director of Nursing turnover was 43.12% and 47.23% respectively.23 Important outcomes such as quality of care have been associated with leadership stability.24,25 A change in administration often had the same challenging effect on implementation of this project. Similarly, when the champion left, implementation efforts practically came to a standstill. Consistent, effective leadership at all managerial levels was key to successful implementation.

Nursing staff turnover has also been high traditionally in NHs, ranging upwards of 100%26 and the inverse relationship between quality of care and staff turnover in NHs has been well-established.27,28,29,30 This is especially troubling when implementing a major change initiative that requires extensive staff training. It was evident from the participant reports that without this consistency of management and staff and the desired change may be delayed or abandoned altogether.

Sustaining the Change Effort

Lewin’s force field analysis includes a final refreezing stage that is as important as the unfreezing and change stages.14 We could see from their reports that a slacking off in implementation was likely to occur if the champion did not continue training, mentoring, and supporting staff efforts. Until a change is fully integrated into the facility’s culture, both structure and processes, the effort to implement it needs to be maintained at a high level.

Interrelation Among Factors

These barriers and facilitators are clearly interrelated, suggesting that one cannot concentrate on one or two of them but should take all of them into consideration when implementing a major change. For example, a scarcity of resources may mean the facility cannot free the champion of other responsibilities but is likely to add this to existing responsibilities thereby limiting time to devote to this project including the necessary staff training and monitoring of their progress. The number of barriers and facilitators noted by the champions and co-champions suggest that it is a combination of strategies that is most effective in successfully implementing a major change initiative. The barriers and facilitators identified in this study may serve as an initial checklist to prepare a plan for the effective launch of a major organizational change in long-term care facilities.

Limitations

Although the project champions were deeply involved in the activities required to successfully implement the INTERACT™ quality improvement program, other stakeholders (administrators, staff, and medical care providers) may have had different perspectives on what constitutes the major barriers and facilitators of implementation. The 17 NHs that dropped out of the intervention group may also have had a different perspective, particularly regarding the barriers to implementation.

Summary

In summary, successful implementation of a major change initiative such as the INTERACT™ quality improvement program requires administrative support including provision of adequate resources to launch and sustain the effort, inclusion of all stakeholders in planning the change, thorough training for everyone involved, a combination of both authority and persuasion on the part of those leading the change, persistence and constant monitoring until the change has become fully integrated into the systems and work processes of the facility and providing as much evidence as possible (in this case data on reductions in 30-day hospital readmission rates) of the positive effects of this considerable effort.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: This project was funded by NIH/NINR Grant #: 5R01NR01236-04. Principal Investigators, Joseph Ouslander and Ruth Tappen. The study received approval from the Florida Atlantic University Institutional Review Board.

We wish to acknowledge the contributions of Alice Bonner, PhD, RN, Laurie Herndon, GNP and Graig Alpert in assisting with conduct of the telephone calls.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Joseph Ouslander has ownership interest in INTERACT™ Training, Education and Management Strategies, LLC (I TEAM). Jill Shutes receives honoraria for training done on behalf of I TEAM. For the remaining authors, none were declared.

Contributor Information

Ruth M. Tappen, Christine E. Lynn College of Nursing, Florida Atlantic University, 777 Glades Road, Bldg. NU-84, Room 307, Boca Raton FL 33431, 954-584-3093.

David G. Wolf, Health Services Administration, School of Professional and Career Education, Barry University, Miami Shores FL.

Zahra Rahemi, Nursing Science, Christine E. Lynn College of Nursing, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton FL.

Gabriella Engstrom, Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton FL.

Carolina Rojido, Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton FL.

Jill M. Shutes, Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton FL.

Joseph G. Ouslander, Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton FL.

References

- 1.Harris-Kojetin L, Sengupta M, Park-Lee E, Valverde R. Long-Term Care Services in the United States: 2013 Overview. Vital & health statistics. Series 3, Analytical and epidemiological studies / [U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Center for Health Statistics] 2013:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ouslander JG, Berenson RA. Reducing Unnecessary Hospitalizations of Nursing Home Residents. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365:1165–1167. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1105449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zinn JS, Brannon D, Mor V. Organizing for nursing home quality. Quality management in health care. 1995;3:37. doi: 10.1097/00019514-199503040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Makos J. What is pest analysis and why it's useful. [Accessed September 26, 2015];PESTLE Analysis website. 2014 Aug 22; http://pestleanalysis.com/what-is-pest-analysis/

- 5.Reaves EL, Musumeci M. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; Dec 15, 2015. [Accessed September 26, 2015]. Medicaid and long-term services and supports: A primer. website: http://kff.org/medicaid/report/medicaid-and-long-term-services-and-supports-a-primer/ [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stefanacci RG. Long-term care regulatory and practice changes: Impact on care, quality, and access. Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging. 2014;22(11):24–28. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen JE. Nursing Home Administration. Seventh. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiener J. An assessment of strategies for improving quality of care in nursing homes. Gerontologist. 2003;43:19–27. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.suppl_2.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raymond JJ, Alday GG, Schwenzer L. Barriers to Implementing Efficient Use of Electronic Medical Records in Long Term Care. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2008;9:B7-B7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wysocki A, Kane RL, Golberstein E, Dowd B, Lum T, Shippee T. The Association between Long-Term Care Setting and Potentially Preventable Hospitalizations among Older Dual Eligibles. Health Services Research. 2014;49:778–797. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jarboe DE. The Effect of a Quality Improvement Initiative on Reducing Hospital Transfers of Nursing Home Residents [unpublished dissertation] Walden University; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stromgaard S, Rasmussen S, Schmidt T. Brief hospitalizations of elderly patients: a retrospective, observational study. Scandinavian Journal OF Trauma Resuscitation & Emergency Medicine. 2014;22:17-17. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-22-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ouslander J, Bonner A, Herndon L, Shutes J. The Interventions to Reduce Acute Care Transfers (INTERACT) Quality Improvement Program: An Overview for Medical Directors and Primary Care Clinicians in Long Term Care. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2014;15:162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewin K. Field Theory in Social Science: Selected Theoretical Papers. 1. New York: Harper; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burnes B. Kurt Lewin and the Planned Approach to Change: A Re-appraisal. Journal of Management Studies. 2004;41:977–1002. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schein EH. Kurt Lewin's Change Theory in the Field and in the Classroom: Notes Toward a Model of Managed Learning. Reflections: The SoL Journal. 1999;1:59–74. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corazzini K, Twersky J, White H, et al. Implementing Culture Change in Nursing Homes: An Adaptive Leadership Framework. Gerontologist. 2015;55:616–627. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banaszak-Holl J, Castle N, Lin M, Spreitzer G. An assessment of cultural values and resident-centered culture change in US nursing facilities. Health Care Management Review. 2013;38:295–305. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0b013e3182678fb0. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shield RR, Looze J, Tyler D, Lepore M, Miller SC. Why and How Do Nursing Homes Implement Culture Change Practices? Insights From Qualitative Interviews in a Mixed Methods Study. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2014;33:737–763. doi: 10.1177/0733464813491141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller SC, Lepore M, Lima JC, Shield R, Tyler DA. Does the Introduction of Nursing Home Culture Change Practices Improve Quality? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2014;62:1675–1682. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lopez SH. Culture Change Management in Long-Term Care: A Shop-Floor View. Politics & Society. 2006;34:55–80. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldaña J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 3. Los Angeles, California: Sage Publishing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perry A. Leadership Turnover in Long-Term Care [white paper] Mission Viejo, CA: Executive Search Solutions; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castle N, Lin M. Top management turnover and quality in nursing homes. Health Care Management Review. 2010;35:161–174. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0b013e3181c22bcb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Castle N. Administrator turnover and quality of care in nursing homes. Gerontologist. 2001;41:757–767. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.6.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mukamel DB, Spector WD, Limcangco R, Wang Y, Feng Z, Mor V. The Costs of Turnover in Nursing Homes. Medical Care. 2009;47:1039–1045. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181a3cc62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Castle NG, Engberg J. Staff Turnover and Quality of Care in Nursing Homes. Medical Care. 2005;43:616–626. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163661.67170.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dellefield M, Castle N, McGilton K, Spilsbury K. The Relationship Between Registered Nurses and Nursing Home Quality: An Integrative Review (2008–2014) Nursing Economics. 2015;33:95-95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen-Mansfield J. Turnover Among Nursing Home Staff: A Review. Nursing Management. 1997;28:59–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knapp M, Missiakoulis S. Predicting turnover rates among the staff of English and Welsh old people's homes. Social science & medicine (1982) 1983;17:29. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(83)90076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]