Abstract

The kidney maintains systemic acid-base balance by reclaiming from the renal tubule lumen virtually all HCO3− filtered in glomeruli and by secreting additional H+ to titrate luminal buffers. For proximal tubules, which are responsible for about 80% of this activity, it is believed that HCO3− reclamation depends solely on H+ secretion, mediated by the apical Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 and the vacuolar proton pump. However, NHE3 and the proton pump cannot account for all HCO3− reclamation. Here, we investigated the potential contribution of two variants of the electroneutral Na+/HCO3– cotransporter NBCn2, the amino termini of which start with the amino acids MCDL (MCDL-NBCn2) and MEIK (MEIK-NBCn2). Western blot analysis and immunocytochemistry revealed that MEIK-NBCn2 predominantly localizes at the basolateral membrane of medullary thick ascending limbs in the rat kidney, whereas MCDL-NBCn2 localizes at the apical membrane of proximal tubules. Notably, NH4Cl-induced systemic metabolic acidosis or hypokalemic alkalosis downregulated the abundance of MCDL-NBCn2 and reciprocally upregulated NHE3. Conversely, NaHCO3-induced metabolic alkalosis upregulated MCDL-NBCn2 and reciprocally downregulated NHE3. We propose that the apical membrane of the proximal tubules has two distinct strategies for HCO3− reclamation: the conventional indirect pathway, in which NHE3 and the proton pump secrete H+ to titrate luminal HCO3−, and the novel direct pathway, in which NBCn2 removes HCO3− from the lumen. The reciprocal regulation of NBCn2 and NHE3 under different physiologic conditions is consistent with our mathematical simulations, which suggest that HCO3− uptake and H+ secretion have reciprocal efficiencies for HCO3− reclamation versus titration of luminal buffers.

Keywords: proximal tubule, bicarbonate reabsorption, acid-base balance, metabolic, acidosis, metabolic alkalosis, mathematical simulation

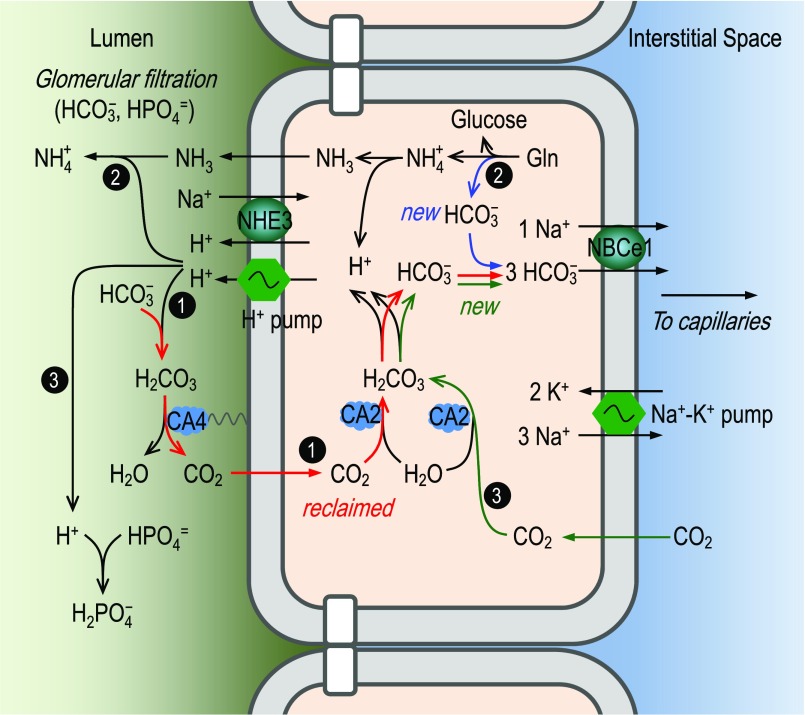

The kidney plays a central role in regulating systemic acid-base balance by controlling the movement of HCO3− from renal tubule cells into the blood. For well over a half century, the consensus has been that this HCO3− traffic—about 80% of which normally occurs in the proximal tubule (PT)—is coupled exclusively with the secretion of H+ into the tubule lumen.1–4 As shown in Figure 1, this H+ secretion is because of the action of the apical Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 (Slc9a3) and vacuolar-type H+ pump. Under normal conditions, the vast majority of the H+ secreted into the PT lumen follows pathway 1 in Figure 1, converting filtered HCO3− to CO2 and H2O, a reaction catalyzed by carbonic anhydrase 4. The CO2 then diffuses into the PT epithelia to recreate HCO3− and H+ under the influence of carbonic anhydrase 2. The HCO3− exits the cell via the basolateral Na+/HCO3− cotransporter NBCe1 (Slc4a4).2,5–7 Pathway 1 (i.e., HCO3− reabsorption) merely reclaims filtered HCO3−, and adds no net HCO3− to the blood.

Figure 1.

Conventional model, in which proximal-tubule HCO3− reclamation depends solely on H+ secretion. In this model, the acid-base traffic across the apical membrane of the proximal tubule occurs via the Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 and a vacuolar-type proton pump. The secreted protons have three major fates: (1) titration of luminal HCO3− to generate CO2, which enters the epithelial cells to recreate HCO3− and H+ (pathway 1); (2) titration of NH3 to form NH4+ (pathway 2); and (3) titration of HPO4=, creatine, and other luminal buffers. In the cytosol of the proximal-tubule epithelium, the protons to be secreted across the apical membrane arise from three sources: (1) hydration of CO2 reclaimed from the lumen (pathway 1); (2) metabolism of glutamine (pathway 2); and (3) hydration of CO2 that enters from the blood (pathway 3). According to this model, HCO3− reclamation and the creation of new HCO3− rely entirely on H+ secretion. All reclaimed HCO3− (pathway 1) and all newly created HCO3− (pathways 2 and 3) move via the basolateral NBCe1 into the interstitial space and finally appear in the blood. For details, see the Introduction. The color of the arrows denotes the flows of carbon in the three different pathways in the proximal tubule.

A tiny fraction of the secreted H+ follows pathways 2 and 3 in Figure 1 to titrate buffers other than HCO3−. In pathway 2, glutamine generates NH3, which enters the lumen and combines secreted H+ to form NH4+, which ultimately appears in the urine. The glutamine metabolism also generates “new HCO3−,” which appears in the blood. In pathway 3, CO2 enters the cell across the basolateral membrane (BLM) to generate (1) more H+, which is secreted into the lumen to titrate other buffers (e.g., HPO4= and creatine); and (2) more new HCO3−, which eventually moves into the blood. It is the new HCO3− generated in pathways 2 and 3 that titrates the H+ generated by body metabolism and traffic across the gastrointestinal tract.

The apical NHE3 and proton pump in Figure 1 can account for most, but not all, HCO3− reclamation by PT. Genetic disruption of Slc9a3 or application of NHE inhibitor N-ethyl-N-isopropyl amiloride (EIPA) reduces HCO3− reclamation (JHCO3) by 50%−60% in the PT.8–11 Blocking the proton pump with bafilomycin (BAF) reduces JHCO3 by 22%–35% in the PT.9,10 Application of BAF in NHE3-null mice reduces JHCO3 by approximately 80% in the PT, compared with JHCO3 in uninhibited wild-type mouse PTs.10 In rats, application of EIPA together with BAF reduces JHCO3 by 76%.9 Consistent with the above perfusion studies, genetic disruption in Slc9a3 reduces plasma [HCO3–] by only 2.5–5 mM, causing mild metabolic acidosis (MAc).10–12 Note that mutations in Slc4a4 often reduce plasma [HCO3–] by more than half, causing severe MAc (for review, see Parker and Boron7 and Romero et al.13). Together, it appears that the apical NHE3 and proton pump are responsible for approximately 80% of JHCO3 by PT. The remaining approximately 20% is likely mediated by apical mechanisms other than NHE3 and proton pump.

Here, we investigate a candidate mechanism potentially underlying the unaccounted-for approximately 20% of JHCO3 in the PT. Previous studies have shown that the rat kidney expresses two groups of full-length NBCn2 (Slc4a10) variants, differing in the amino termini (Nts), one starting with residue MCDL (mainly NBCn2-G), and the other with MEIK (mainly NBCn2-C).14,15 Here, we report that MCDL-NBCn2 is expressed at the apical membrane of the PT, whereas MEIK-NBCn2 is expressed at the BLM of the medullary thick ascending limb (mTAL) and inner medullary collecting ducts (IMCDs). Systemic acid-base disturbances reciprocally regulate the abundances of MCDL-NBCn2 and NHE3. Our data are consistent with the hypothesis that PT apical membranes reabsorb HCO3− by two strategies. The major one is the classic indirect CO2 pathway, depending on H+ secretion by the apical NHE3 and proton pumps. The minor one is the direct HCO3– pathway, in which NBCn2 transfers HCO3− across the apical membrane.

Results

Distribution and Localization of NBCn2 in the Rat Kidney

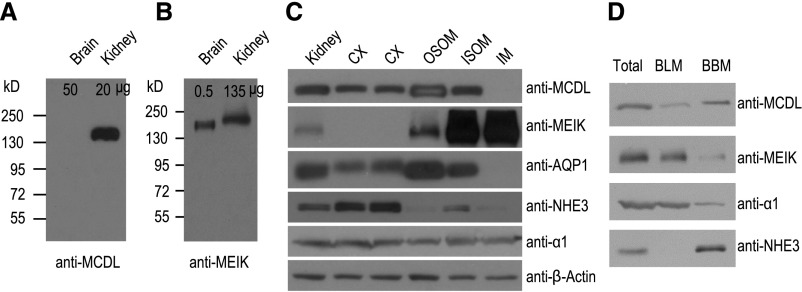

Consistent with previous observations,14 anti-MCDL recognizes a band of apparent molecular mass approximately 150 kD from the rat kidney, but not the brain (Figure 2A). Anti-MEIK recognizes bands of apparent molecular mass approximately 180 kD from the brain and approximately 190 kD from the kidney (Figure 2B). The difference between the apparent and predicted molecular masses (approximately 125 kD) reflects N-glycosylation of NBCn2 proteins (see Liu et al.14 and Chen et al.16, and Supplemental Material). The difference in the apparent molecular mass of MEIK-NBCn2 in the brain and kidney presumably reflects differences in MEIK-NBCn2 variants and glycosylation in these tissues (Supplemental Material).

Figure 2.

Distinct distribution of MCDL-NBCn2 and MEIK-NBCn2 in rat brain and kidney, and in subcellular fractions of kidney. (A and B) Expression of MCDL-NBCn2 and MEIK-NBCn2 in the rat brain and kidney. The numbers above each lane indicate the amount of total membrane proteins loaded into the lane for SDS-PAGE. (C) Distribution of NBCn2 variants in various tissues of rat kidney. We loaded 40 μg of total membrane proteins into each lane. β-actin was probed to verify equal loading in each lane. (D) Distribution of NBCn2 variants in basolateral versus BBMs. In (D), equal volumes of the total, BLM, and BBM preparations (see Concise Methods for details) were loaded into each lane for SDS-PAGE and Western blotting in such a way that, in theory, the amount of a given protein in total equals the sum of the amounts of this protein in BBM and BLM. Although this is true for MCDL, MEIK, and α1, the exclusively apical NHE3 paradoxically generates a stronger signal in BBM than in total. AQP1, aquaporin 1.

MCDL-NBCn2 is primarily expressed in the cortex (CX), outer stripe of outer medulla (OSOM), and inner stripe of outer medulla (ISOM), but not detectable in the inner medulla (IM) in rat kidneys (Figure 2C). In contrast, MEIK-NBCn2 is predominantly expressed in the ISOM and IM. Consistent with previous studies,17–19,40 we show that AQP1 is predominantly expressed in the CX, OSOM, and ISOM; NHE3 is predominantly expressed in the CX; and the α1 subunit of Na+-K+ pump (α1) is expressed throughout the kidney (Figure 2C). Thus, MCDL-NBCn2 has a tissue distribution similar to that of AQP1 in rat kidneys.

In isolated BLMs and brush border membranes (BBMs) from rat kidneys, MCDL-NBCn2 is mainly distributed in the BBM, whereas MEIK-NBCn2 is predominantly distributed in the BLM (Figure 2D). The observations that α1 (basolateral marker) is primarily basolateral but NHE3 (apical marker) is predominantly apical confirm our separation of the BLM and BBM. Together, our data indicate that MCDL-NBCn2 and MEIK-NBCn2 have distinct tissue and subcellular distributions in the rat kidney. MCDL-NBCn2 is predominantly expressed in the apical membranes in the CX, OSOM, and ISOM, whereas MEIK-NBCn2 is predominantly expressed in the BLMs of the ISOM and IM.

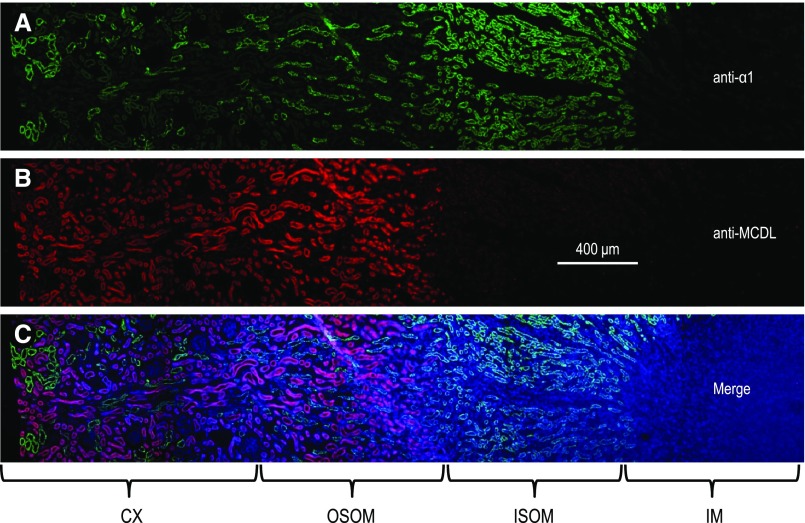

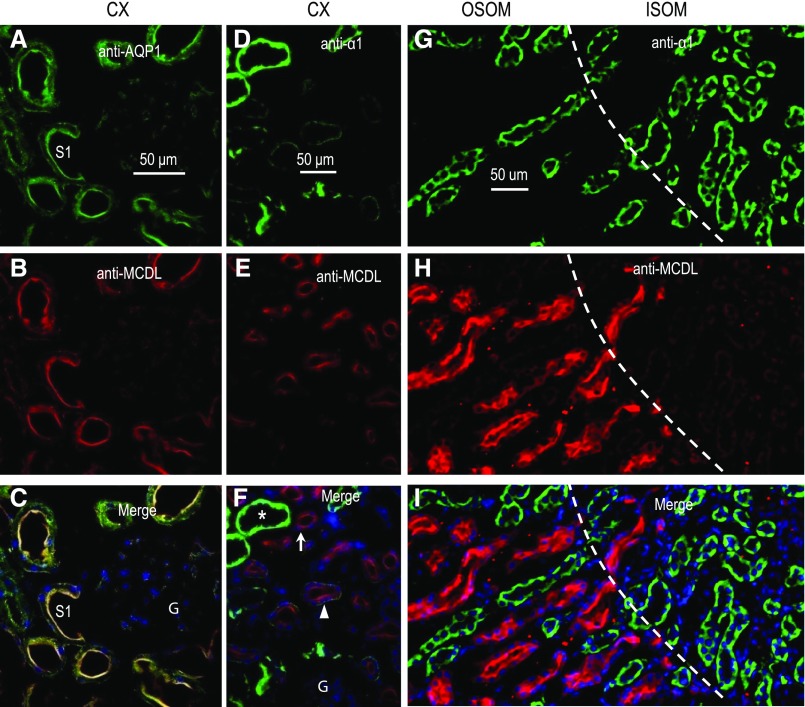

Consistent with the data in Figure 2, C and D, immunocytochemistry shows that MCDL-NBCn2 is predominantly expressed in the CX and OSOM of rat kidney (Figures 3 and 4). Immunodepletion with the Nt of MCDL-NBCn2 eliminates the fluorescence (Figure 3B, inset), suggesting that the immunofluorescence signal is specific. A higher magnification view shows that MCDL-NBCn2 colocalizes with AQP1 in the apical membrane of tubules in the CX (Figure 5, A–C). Moreover, in the CX and OSOM, tubules enriched in MCDL-NBCn2 exhibit relatively low expression of α1, whereas those lacking MCDL-NBCn2 exhibit very strong expression of α1 (Figure 5, D–I). Others have shown that α1 is highly enriched in all segments, from the mTAL through to the cortical collecting tubule, but is much lower in the PTs of the rat kidney.17,20 Indeed, in the CX, the tubules enriched in α1 account for only a small fraction of total tubules (Figures 4 and 5, D–F), consistent with our conclusion that these α1-enriched cortical structures are not PTs. In the OSOM, tubules lacking MCDL-NBCn2 but highly enriched in α1 are presumably mTALs. Considering all of these data, we conclude that, in the rat kidney, MCDL-NBCn2 is expressed in the apical membrane of PTs but not in the mTAL through to the cortical collecting tubule.

Figure 3.

Overview showing colocalization of AQP1 and MCDL-NBCn2 in the rat kidney. A section of rat kidney was costained with (A) anti-AQP1 (a specific marker for the PT and thin descending limb of Henle), (see refs. 17, 19, 40), and (B) anti-MCDL directed against NBCn2, and counterstained with DAPI. (C) shows the merge of (A and B) plus DAPI. The figure was generated from images of five contiguous regions. In the CX and OSOM, MCDL-NBCn2 staining is seen in the tubules enriched in AQP1 expression. The inset in (B) shows a section stained with anti-NBCn2 that has been immunodepleted with GST-NBCn2-Nt.

Figure 4.

Overview showing differential localization of the α1 subunit of the Na+-K+ pump and MCDL-NBCn2 in rat kidney tubules. A section of rat kidney was costained with (A) anti-α1 (a specific marker for the BLM of renal tubules), (see refs. 17, 20), and (B) anti-MCDL. The section was counterstained with DAPI. (C) shows the merge of (A and B) plus DAPI. The figure was generated from images of five contiguous regions. The distribution profile of MCDL-NBCn2 is distinct from that of the α1 subunit of Na+-K+ pump, with the tubules that are positive for MCDL-NBCn2 expression having low expression of α1.

Figure 5.

High-magnification view showing apical localization of MCDL-NBCn2 in proximal tubules of rat kidney. (A–C) Section of renal CX costained with anti-AQP1 and anti–MCDL-NBCn2. (D–F) Section of renal CX costained with anti-α1 subunit of Na+-K+ pump and anti–MCDL-NBCn2. (G–I) Section of the OSOM and ISOM costained with anti-α1 and anti–MCDL-NBCn2. The star indicates a tubule a high level of expression of the Na+-K+ pump; the triangle, a tubule with less expression; and the arrow, a tubule with no visible expression of Na+-K+ pump. The dashed lines in (G–I) represent the demarcation between OSOM and ISOM. S1, the s1 segment of proximal tubule; G, glomerulus.

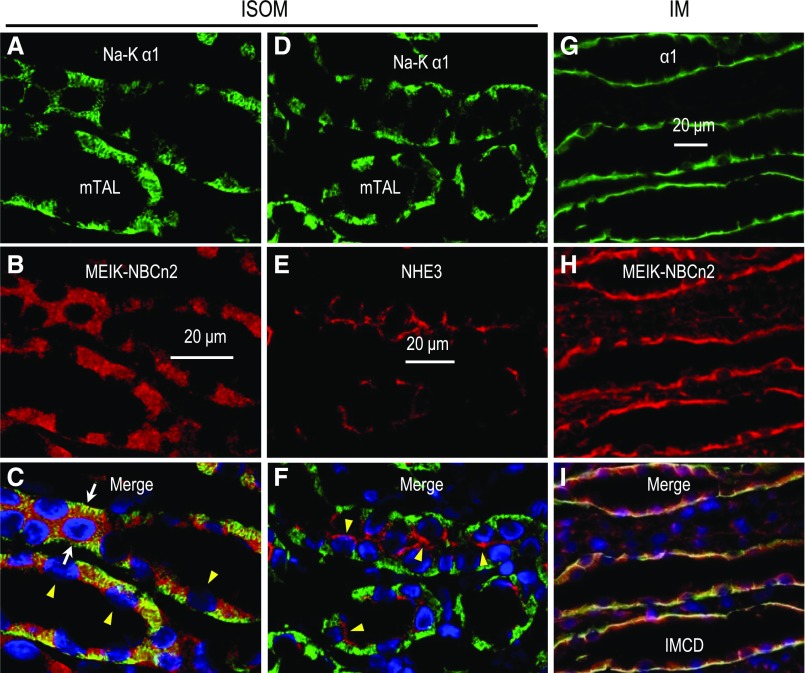

In the ISOM (Figure 6, A–C), MEIK-NBCn2 is localized at the BLMs of structures highly enriched in α1, characteristic of the BLM of the mTAL.17,20 Figure 6, D–F shows the basolateral localization of α1 and the apical localization of NHE3 in the mTAL. In the IM (Figure 6, G–I), MEIK-NBCn2 also colocalizes with α1 at the BLM of structures that are presumably IMCDs. The basolateral localization of MEIK-NBCn2 is consistent with Figure 2D. Thus, it is likely that MEIK-NBCn2 is localized at the BLMs of mTALs in the ISOM, and of IMCDs in the IM.

Figure 6.

High magnification view showing basolateral localization of MEIK-NBCn2 in the mTAL of the ISOM, as well as in the IMCD of rat kidney. (A–C) A section of renal ISOM, costained with anti-α1 subunit of Na+-K+ pump and anti-MEIK. (D–F) A section of the renal ISOM, costained with anti-α1 and anti-NHE3. (G–I) A section of the renal IM, costained with anti-α1 and anti–MEIK-NBCn2. Strong labeling of MEIK-NBCn2 was observed at the BLM of mTALs. The labeling of MEIK-NBCn2 was also observed, to a weaker level, at the BLM of IMCDs. The white arrows in (C) indicate the tubules that were cut through the tubule wall mostly parallel to the long axis of the lumen; therefore, the nucleus is surrounded by BLMs. The arrowheads in (C and F) indicate the approximate locations of BBMs (on the side of the nuclei abutting the tubule lumen). Note that the BBMs indicated by arrowheads in (C) are invisible because of the lack of any staining.

Effect of NH4Cl-Induced MAc on NBCn2 Expression in the Kidney

We were surprised to find MCDL-NBCn2 in the apical membrane of the PT. Here, NBCn2 would mediate Na+/HCO3− influx from the tubule lumen to the cytosol. To address the physiologic relevance of the apical MCDL-NBCn2 in PTs, we investigated the effects of systemic acid-base disturbances on the expression of MCDL-NBCn2 and NHE3 in the rat kidney.

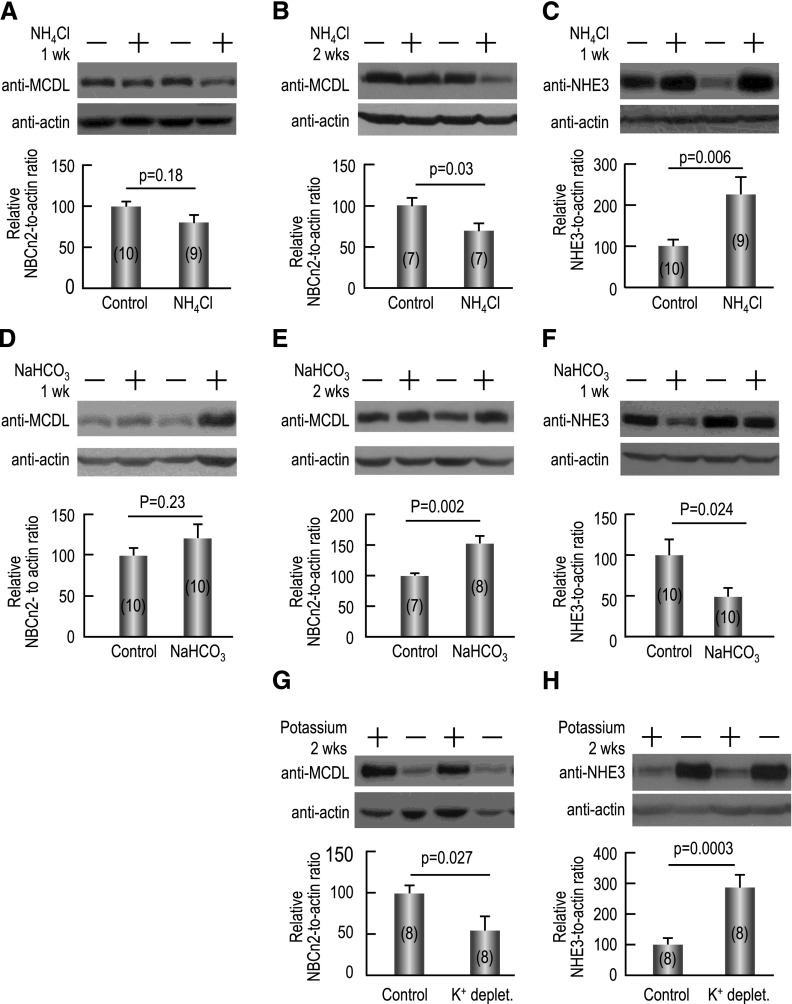

As shown in Figure 7A, NH4Cl-induced MAc for 1 week lowers the abundance of MCDL-NBCn2 in the rat kidney by approximately 20% compared with the control condition (no MAc), although this difference is not statistically significant (see Supplemental Table 1 for detailed MCDL-NBCn2 data). NH4Cl treatment for 2 weeks decreases MCDL-NBCn2 abundance by approximately 31% (P=0.03; Figure 7B). As shown in Figure 7C, compared with control, NH4Cl treatment increases NHE3 abundance by approximately 127% in rat kidneys after 1 week (P<0.01; see Supplemental Table 2 for detailed NHE3 data), and by approximately 97% after 2 weeks (P=0.003; data not shown), consistent with previous reports.21–25 Thus, the expression of MCDL-NBCn2 and NHE3 are inversely regulated by NH4Cl-induced MAc.

Figure 7.

Inverse regulation of the expression of MCDL-NBCn2 and NHE3 in rat kidney by systemic acid-base disturbances. (A) Effect of 1 week of NH4Cl overload on MCDL-NBCn2. Here, 1.5% NH4Cl was in drinking water only. (B) Effect of 2 weeks of NH4Cl overload on MCDL-NBCn2. Here, 1.5% NH4Cl was in the drinking water and 2% in the chow (with the rats being fed normal chow every third day). (C) Effect of 1 week of NH4Cl overload on NHE3. (D) Effect of 1 week of NaHCO3 overload on MCDL-NBCn2. (F) Effect of 2 weeks of NaHCO3 overload on MCDL-NBCn2. (F) Effect of 1 week of NaHCO3 overload on NHE3. (G) Effect of 2 weeks of potassium depletion on MCDL-NBCn2. (H) Effect of 2 weeks of potassium depletion on NHE3. The top of each panel shows representative Western blots of the corresponding transporters and β-actin for the normalization of loading. The bar graph at the bottom of each panel shows the summary of densitometry data (presented as mean±SEM) from the blots like those shown on the top. Two-tailed paired t tests were performed for statistical analysis.

Effect of NaHCO3-Induced Metabolic Alkalosis on NBCn2 Expression in the Kidney

NaHCO3 overload induces metabolic alkalosis (MAlk). In this study, treatment with NaHCO3 for 1 week raises the mean abundance of MCDL-NBCn2 by approximately 21% in the kidney compared with controls, although this difference is not significant (Figure 7D). However, extending the NaHCO3 treatment to 2 weeks increases MCDL-NBCn2 abundance by approximately 52% (P=0.002; Figure 7E). Conversely, we find that, compared with control, NaHCO3 overload decreases NHE3 abundance by approximately 50% in rat kidneys after 1 week (P=0.02; Figure 7F), and approximately 46% after 2 weeks (P<0.01; data not shown). This last observation is consistent with previous studies showing that NaHCO3-induced MAlk substantially downregulates renal NHE3 expression.21,26 NaCl overload does not significantly change the abundance of MCDL-NBCn2 in rat kidney compared with controls (Supplemental Figure 1), ruling out an effect of Na+ overload per se on the interpretation of our NaHCO3 data. Thus, our NaHCO3-induced MAlk data provide a second example of an inverse relationship between the regulation of renal MCDL-NBCn2 and NHE3 expression.

Effect of Hypokalemic Alkalosis on NBCn2 Expression in the Kidney

Potassium depletion causes hypokalemic alkalosis, presumably by stimulating the production and secretion of NH4+ in PTs.27,28 Indeed, potassium depletion substantially increases the abundance of NHE3 in rat kidneys.29

Here, we find that potassium depletion for 2 weeks decreases MCDL-NBCn2 abundance by approximately 45% (P<0.03; Figure 7G) but increases NHE3 expression by approximately 121% in the rat kidney (P<0.01; Figure 7H). Our hypokalemic data provide a third example of an inverse relationship between the regulation of MCDL-NBCn2 and NHE3 expression.

Discussion

In rats, the Slc4a10 gene can give rise to multiple NBCn2 variants that fall into two major groups. Depending on the usage of different promoters,15 the extreme Nt of these variants can begin either with MCDL (NBCn2-E/F/G/H) or MEIK (NBCn2-A/B/C/D). In the MCDL group, the rat kidney mainly expresses NBCn2-G, and in the MEIK group, it expresses mainly NBCn2-C.14,15 Here, we find that MCDL-NBCn2 and MEIK-NBCn2 exhibit distinct tissue and subcellular distributions in rat kidney, with MCDL-NBCn2 being localized in the apical membrane of PTs, and MEIK-NBCn2 localized in the BLM of mTALs and IMCDs.

The basolateral localization of MEIK-NBCn2 in the mTAL parallels that of NBCn1.24,30 Because NBCn1 contributes to NH4+ reabsorption in the mTAL, MEIK-NBCn2 likely does the same.

The apical localization of MCDL-NBCn2 in PTs suggests that the cell can directly reclaim HCO3− per se or a related species (e.g., CO3= or NaCO3–)—collectively referred to as “HCO3−” hereafter—across the apical membrane of the PT. Figure 8 summarizes our new model for the molecular mechanisms underlying HCO3− reclamation in the PT. We propose that the apical membrane of PTs reclaims HCO3− by two distinct strategies: the conventional indirect CO2 pathway 1 and the novel HCO3− pathway 4 (Figure 8). The conventional CO2 pathway couples HCO3− reclamation to proton secretion by apical NHE3 and vacuolar H+ pump, thereby generating CO2 and H2O, which then diffuse across the apical membrane for eventual reconstruction of the original HCO3− in the cytosol of the PT cell. In contrast, the HCO3− pathway moves luminal HCO3− directly into the cytosol of the epithelia. Although not shown in Figure 8, the direct uptake of HCO3− from the lumen would also indirectly generate luminal H+ for the titration of other luminal buffers (Supplemental Figure 2). In a steady state, the sum of apical fluxes of CO2 (JCO2AP) and HCO3− (JHCO3AP) represents the total disappearance of HCO3− from PT lumen. As noted in the Introduction, the PT retains approximately 20% of its JHCO3 even after disruption/inhibition of both NHE3 and proton pump. We propose that the apical NBCn2 accounts for this remaining JHCO3.

Figure 8.

New model, in which proximal-tubule HCO3– reclamation depends on both H+ secretion (conventional indirect pathways #1, 2, and 3) and HCO3– reabsorption (novel direct pathway #4). In the PT, HCO3− is reclaimed from the lumen via two distinct mechanisms: (1) pathway 1 as described in Figure 1; (2) the novel pathway 4, in which HCO3− (or a HCO3−-related species like CO3= or NaCO3–) is directly reabsorbed by the apical Na+/HCO3− cotransporter NBCn2. The total flux of CO2 across the apical membrane (JCO2AP) via pathway 1 and the total flux of HCO3− across the apical membrane (JHCO3AP) via pathway 4 represent the total HCO3− reclaimed by the PT cells, which accounts for approximately 80% of total HCO3− reclamation by the kidney. Of the 80% of HCO3− reclaimed by the PT, pathway 1 is responsible for approximately 80%, thereby accounting for approximately 65% of the total HCO3− reclamation by the kidney. We propose that pathway 4 is responsible for the remaining approximately 20% of the approximately 80% of the total filtered HCO3− that is reclaimed by the PT, thereby accounting for approximately 15% of the total HCO3− reclamation by the kidney. Inside the PT cells, the CO2 that entered across the apical membrane (pathway 1) is converted to HCO3−. This HCO3− from pathways 1 and 4 diffuses to the BLM. In addition to these two routes of HCO3− reclamation, the PT cell generates new HCO3− in pathway 2 (glutamine metabolism) and pathway 3 (hydration of CO2 derived from the blood). The HCO3– efflux across the BLM (JHCO3BL, presumably all via NBCe1) equals the sum of the reclaimed and new HCO3− (i.e., JHCO3BL=JCO2AP+JHCO3AP+JHCO3new). The color of the arrows denotes the flows of carbon in the four different pathways in the PT.

The apical MCDL-NBCn2 that we demonstrate here is consistent with a previous study identifying 4,4′-diisothiocyanostilbene-2,2′-disulfonate (DIDS)–sensitive acid-base transport at the apical membrane of rat PTs.31 Luminal DIDS reduces fluid reabsorption (JV) by approximately 19% in rat PTs,31 a fraction consistent with the unaccounted-for approximately 20% of JHCO3 (see Introduction). Moreover, the inhibitory effect of luminal DIDS on JV requires the presence of HCO3−.32 It is true that, in rabbit PTs, luminal 4-acetamido-4′-isothiocyanostilbene-2,2′-disulfonate—administered at the same time luminal Na+ is removed—has no effect on the intracellular acidification induced by Na+ removal.33 This apparent inconsistency with our hypothesis could reflect a species specificity or, more likely, insufficient time for luminal 4-acetamido-4′-isothiocyanostilbene-2,2′-disulfonate to block NBCn2 before the reversal of Na+-coupled transporters was well underway.

One question that arises is whether the direct HCO3− pathway via apical NBCn2 serves merely as a back-up for the indirect CO2 pathway, which depends on the apical NHE3 and vacuolar proton pump. If so, then we would expect systemic acid-base disturbances to affect all of these transporters in parallel. However, we find that the regulation of the protein abundances of NBCn2 and NHE3 are strikingly reciprocal. Under chronic NH4Cl-induced MAc or hypokalemic alkalosis for 2 weeks, the protein abundance of NHE3 is substantially upregulated, as is well established by previous work21–25,29 and confirmed in this study. Conversely, the protein abundance of MCDL-NBCn2 is markedly downregulated. In contrast, under chronic NaHCO3-induced MAlk, MCDL-NBCn2 is upregulated, whereas NHE3 is downregulated. Thus, we conclude that NBCn2 cannot be merely a back-up pathway for HCO3– reclamation.

A second question that arises is whether the reciprocal regulation of MCDL-NBCn2 and NHE3 in the PT confers a functional advantage for the animal. Is it possible that the two pathways have different efficiencies for new HCO3− creation (accounting for 1%–2% of total PT acid-base traffic under physiologic conditions) on the one hand and HCO3− reclamation (accounting for the remaining 98%–99%) on the other? One approach for addressing this question is to simulate mathematically the effects of apical H+ extrusion versus apical HCO3− uptake. Because a reaction–diffusion model for CO2/HCO3− and various buffers does not exist for PTs, we adapt an existing Xenopus oocyte model,34,35 with the goal of providing a proof of principle. As outlined in Supplemental Figure 2, we simulate three models: (1) extrusion of H+ across a cell membrane, (2) uptake of the same amount of HCO3−, or (3) uptake of half that amount of CO3= (i.e., same number of acid-base equivalents). Note that both NHE3 and NBCn2 are energized by the coupled influx of one Na+, and carry the same number of acid-base equivalents. For each model, we compute the fraction of acid-base transport across the membrane used to (1) titrate the weak base A– (a surrogate for non-HCO3 buffers like NH3 and HPO42−) to its conjugate weak acid HA (e.g., H2PO4−) in a thin layer of extracellular fluid near the membrane, and (2) reclaim HCO3− from this same thin layer. Also, for each model, we perform simulations at two values of bulk extracellular pH (pHo), 7.50 (standard oocyte pHo, mimicking luminal pH near the beginning of the PT) and 7.10 (mimicking luminal pH further down the PT), and at two values of the extracellular surface CA acceleration factor (Aos), 25,000 (extremely high Aos that approximates erythrocyte cytoplasm) and 150 (approximating the surface of the control Xenopus oocyte).

As summarized in Table 1, our simulations predict that the H+ extrusion model is most efficient for A– titration but least efficient for HCO3− reclamation, whereas the HCO3− uptake model is just the opposite. The CO3= model makes intermediate predictions. The discrepancies among models (i.e., efficiency of A– titration versus HCO3− reclamation) increase as pHo increases (7.10 → 7.50), and Aos decreases (25,000 → 150). For example, at pHo 7.50, H+ extrusion is more efficient than HCO3– uptake for A– titration (a process essential for the formation of new HCO3− that titrates the net acid generated in the body) by approximately 26% at Aos=25,000, and by approximately 750% at Aos=150. The PT probably lies between these two values. During MAc, the upregulation of NHE3 (at the expense of MCDL-NBCn2) is energetically advantageous for the critical need of increasing new HCO3− generation (which requires increasing luminal A– titration) to return blood pH toward normal. Upregulation of NHE3 is specifically not required for HCO3− reclamation because the HCO3– load to the PT naturally falls during MAc. Of course, the preexisting levels of NHE3 and NBCn2 were already adequate to reclaim larger HCO3– loads under normal acid-base conditions. Thus, during MAc it is energetically advantageous to decrease HCO3−-reclamation capacity by downregulating MCDL-NBCn2. Conversely, in situations like MAlk, where the kidney must decrease new HCO3− generation to return blood pH toward normal, it is energetically advantageous to reduce A– titration by downregulating NHE3. Because MAlk simultaneously increases the HCO3− filtered load, the kidney must increase HCO3− reclamation, which it achieves most efficiently by upregulating MCDL-NBCn2.

Table 1.

Results of mathematical simulations

| Surface CA Acceleration Factor | Model | pHo=7.50 | pHo=7.10 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 H+, % | 2 HCO3–, % | 1 CO3=, % | 2 H+, % | 2 HCO3–, % | 1 CO3=, % | ||

| 25,000 | A− titration | 2.25 | 1.79 | 2.02 | 4.47 | 3.76 | 4.11 |

| HCO3– reclamation | 97.76 | 98.21 | 97.98 | 95.54 | 96.25 | 95.89 | |

| 150 | A− titration | 11.95 | 1.40 | 6.66 | 18.54 | 3.0 | 10.83 |

| HCO3– reclamation | 88.04 | 98.60 | 93.33 | 81.41 | 97.01 | 89.12 | |

We use three different reaction–diffusion models for a spherical cell (extrusion of two H+ ions, uptake of two HCO3− ions, or uptake of 1 CO3= ion) to simulate at two different bulk extracellular pH (pHo) values and two different sets of CA activities—the fraction of total traffic of acid-base equivalents across the cell membrane that results in titration of extracellular A– versus reclamation of extracellular HCO3−. For details, see Supplemental Material. Note that we captured these data 30 seconds into a simulation in which we initiate acid-base transport at 0 seconds. Data summaries for simulations at 10 and 100 seconds are shown in Supplemental Table 4.

MCDL-NBCn2 and NHE3 are also under reciprocal regulation during hypokalemic alkalosis, an observation that raises the possibility that one set of controls reciprocally modulates the expression of these two proteins in the PT. Note that we have not simulated the titration of NH3 to NH4+ in the extracellular fluid. Also, we have not considered the possibility, raised by Kinsella and Aronson,36 that NHE3 may, to some extent, engage in Na+-NH4+ exchange.

In summary, we find that the Na+/HCO3– cotransporter MCDL-NBCn2 is expressed at the apical membrane of renal PTs. We suggest that the apical PT membrane uses two strategies for HCO3– reclamation, with different acid-base consequences: the indirect CO2 pathway depending on the H+ secretion by the apical NHE3, and the direct HCO3– pathway depending on the apical MCDL-NBCn2. The PT reciprocally regulates MCDL-NBCn2 and NHE3 under conditions that require reciprocal modulation of HCO3– reclamation versus new HCO3– creation. Indeed, our mathematical simulations show that these two pathways, appropriately, have reciprocal efficiencies for HCO3− reclamation versus creation of new HCO3−. These predictions call for testing in future studies. Nevertheless, our findings about the direct HCO3– pathway for HCO3– reclamation in the apical membrane of PT are of fundamental importance for understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying the regulation of renal acid-base balance in health and disease.

Concise Methods

Antibodies and Fusion Protein

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against NBCn2, including anti-MCDL and anti-MEIK, were generated by Genscript (Nanjing, China). Anti-MCDL directed against SGNRKVMQPGTCEHC in the unique Nt of MCDL-NBCn2 has been described previously,14 and is further characterized in this study (see Supplemental Figures 1, A–C and 2, A–C). Anti-MEIK was directed against MEIKDQGAQMEPLLPTC, an epitope in the unique portion of the Nt of MEIK-NBCn2 that has been well characterized previously.37 The underlined Cys residues were artificially introduced for conjugating the peptide to keyhole limpet hemocyanin for immunizing rabbits. All these polyclonal antibodies were affinity-purified with the corresponding immunizing peptides. Goat anti-AQP1 was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (catalog no. sc-9878). Mouse anti-α1 (catalog no. ab-7671) against the α1 subunit of Na+-K+ pump and mouse anti-NHE3 (catalog no. ab-95299) were purchased from Abcam (Hong Kong). Mouse anti-actin was purchased from Beyotime (catalog no. AA128; Jiangsu, China).

Secondary antibodies conjugated with HRP for Western blotting were goat anti-rabbit (catalog no. A0208) and goat anti-mouse (catalog no. A0216) from Beyotime, and donkey anti-goat (catalog no. SA00001–3) from ProteinTech Group, Inc. (Chicago, IL). Secondary antibodies used for immunocytochemistry were Alexa Fluor 488 AffiniPure goat anti-mouse (catalog no. 115–545–003) and Alexa Fluor 488 AffiniPure donkey anti-goat (catalog no. 705–545–003) from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA), and DyLight 549 goat anti-rabbit (catalog no. E032320–01) from EarthOx (Millbrae, CA).

The construct for recombinantly expressing fusion protein GST-MCDL-Nt, consisting of glutathione-S-transferase and the Nt of MCDL-NBCn2, was described previously.14 The fusion protein was expressed in bacteria and affinity-purified with glutathione-S-transferase resin (Genscript) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Animals

Adult Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats with 200–300 g body wt were used to examine the effects of systemic acid-base disturbances on the expression of renal acid-base transporters. For NH4Cl overload, rats from the same batch were randomly assigned to one of two groups. One group was supplied with drinking water containing 1.5% NH4Cl plus 0.5% sucrose for 1 week. The other (control) was supplied with water containing 0.5% sucrose only. The rats had free access to drinking water and were supplied with regular rodent chow. In other experiments, to maximize the acid load, the rats were treated with NH4Cl both in drinking water and chow as described previously,22,38 with slight modifications. Briefly, the acidotic rats had drinking water containing 1.5% NH4Cl plus 0.5% sucrose, and chow containing 2% NH4Cl (replaced with normal chow every third day). The NH4Cl chow was prepared by mixing powdered regular chow and 3% NH4Cl solution with a ratio of 4:3 (wt/vol). The control rats were pair-fed with water containing 0.5% sucrose and regular chow. After 1 or 2 weeks, the rats were anesthetized by subcutaneous injection of pentobarbital sodium and euthanized for tissue collection.

For NaHCO3 overload, adult SD rats were randomly assigned to one of two groups. One was supplied with water containing 0.28 M NaHCO3 for 1 or 2 weeks. The control group was supplied with plain water. After the treatment, the rats were then euthanized for tissue collection.

For hypokalemic alkalosis, the rats were fed with either potassium-depleted chow (catalog no. TP0901–01M, potassium level of 0.01%) or standard AIN93 chow (catalog no. LAD3001M, potassium level of 0.36%) purchased from Trophic Animal Feed High-Tech Co. Ltd. (Jiangsu, China). The control rats had a limited supply of chow, so that they had similar caloric intakes compared with the potassium-depletion group. All rats had free access to ultrapure water. The rats were treated for 2 weeks and then euthanized for tissue collection.

Membrane Protein Preparation and Western Blotting

Rat kidney tissue (approximately 500 mg) was placed in 6 ml of precooled protein isolation buffer (7.5 mM NaH2PO4, 250 mM sucrose, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA, pH 7.0) containing 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (catalog no. P8340; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and homogenized by 15 strokes with a Glas-Col Teflon glass homogenizer (Glas-Col, Terre Haute, IN). The crude homogenate was centrifuged at 3000×g for 10 minutes at 4°C to remove the cell debris. The supernatant was then centrifuged at 100,000×g for 60 minutes at 4°C. The pellet containing the plasma membranes was resuspended in buffer containing 20 mM Tris, 5 mM EDTA, 5% SDS, pH 8.0. The protein concentration was determined with Enhanced BCA Protein Assay Kit (catalog no. P0010; Beyotime). The protein preparations were stored in aliquots at −80°C until usage.

BBMs and BLMs were prepared from whole rat kidneys by MgCl2 precipitation, as described previously,39 with slight modifications. Briefly, 250 mg of rat kidney tissue was homogenized in 6 ml of precooled protein isolation buffer and centrifuged at 3000×g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was then ultracentrifuged at 48,000×g for 1 hour. The resultant pellet was resuspended in 500 μl of protein isolation buffer and 100 μl of this resuspension was saved as the “total” membrane protein. The remaining 400 μl was diluted with 2.5 ml of protein isolation buffer and 45 μl of 1 M MgCl2, and then incubated at 4°C for 20 minutes. The samples were centrifuged at 3000×g for 10 minutes at 4°C to collect the precipitated membrane proteins. The supernatant was subjected to two more rounds of MgCl2 precipitation. The pellets from all three rounds of centrifugation were pooled, resuspended in 400 μl of protein isolation buffer, and used as BLMs. The supernatant from the last MgCl2 precipitation was centrifuged at 48,000×g at 4°C for 30 minutes. The resultant pellet was resuspended in 400 μl protein isolation buffer and used as BBMs.

For Western blotting, the membrane proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and then blotted onto a PVDF membrane. The blot was blocked with 5% milk in TBST (1 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20, pH 7.4) for 1 hour at room temperature (RT). The blot was then probed with primary antibody in TBST containing 1% milk at 4°C overnight. The blot was washed five times with TBST, incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody in TBST containing 1% milk for 1 hour at RT, and then washed five times with TBST. The blot was treated with SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent reagent (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) before x-ray exposure.

Immunocytochemistry

Adult SD rats were fixed by transcardial perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS buffer (77.4 mM Na2HPO4, 22.6 mM NaH2PO4, pH 7.4). The kidneys were collected and stored in PBS containing 0.1% PFA plus 0.02% NaN3 until usage for cryo-section. For immunocytochemical staining, a section of 5 μm was incubated in 60°C overnight and then rehydrated in TBS for 60 minutes. The section was treated at 98°C for 20 minutes in Improved Citrate Antigen Retrieval Solution (catalog no. P0083; Beyotime). After washing five times with TBS, the section was blocked with Immunol Staining Blocking Buffer (catalog no. P0102; Beyotime) for 30 minutes, and then incubated with primary antibody at 4°C overnight. The section was washed five times with TBS and incubated with secondary antibody at RT for 60 minutes. After washing three times with TBS, the section was counterstained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole at RT for 5 minutes, washed three times with TBS, and mounted with Antifade Polyvinylpyrrolidone Medium (catalog no. P0123; Beyotime). Images were acquired on a FluoView FV1000 confocal microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Mathematical Simulations

A time-dependent reaction–diffusion model of transmembrane CO2 fluxes in a Xenopus oocyte was adapted to simulate the effects of apical H+ extrusion versus apical HCO3− uptake in the PT.34 Here, we briefly summarize the main features of these models. For details on the theory behind the models and on the numerical implementation, refer to the first-generation model described previously.35 The second-generation model includes refinements that lead to more realistic simulations of an oocyte exposed to a solution containing equilibrated CO2/HCO3−.34

The starting point for the simulations in this study is the second-generation model of a CAIV oocyte (i.e., an oocyte expressing carbonic anhydrase 4). The model assumes that the oocyte is a symmetric spherical cell surrounded by a thin spherical layer of extracellular unconvected fluid (EUF) of thickness d=10 μm. The EUF is surrounded by the bulk extracellular fluid, which is an infinite reservoir of pre-equilibrated solution. In the intracellular fluid and EUF, diffusion of solutes (CO2, H2CO3, HCO3−, H+, HA, and A−) and reactions among solutes (CO2 hydration/dehydration, carbonic acid dissociation, and HA dissociation) occur. In this study, we extend the second-generation model to include the uptake of one CO3= ion; we therefore include the new solute CO3= (assumed to have the same mobility as HCO3−) and model the reaction HCO3−⇄CO3=+H+, with pK=10.2258 at 22°C. Moreover, in this study, in order to mimic inorganic phosphate in the PT lumen, we assume that the extracellular HA/A− buffer has a pK=6.8 and [HA]+[A−]=0.7 mM. Finally, we assume that the acceleration factor for extracellular surface CA activity is 25,000 (or 150) and that the acceleration factor for cytosolic CA activity is 20 (or 5). All other parameter values are the same as described previously (see Supplemental Material for further details).34,35

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

W.F.B. gratefully acknowledges the support of the Meyers/Scarpa Chair. The authors are thankful to Dr. Fraser J. Moss at Case Western Reserve University for testing the sensitivity of rat NBCn2-G to 1 mM SITS in Xenopus oocytes.

This work was supported by grants 31371171(to L.-M.C.), 81571388 (to L.-M.C.), and 31571201 (Y.L.) from the National Science Foundation of China, grant 2016YXMS263 (to Y.L.) from the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China, grants U01-GM111251 (W.F.B.) and K01-DK107787 (R.O.) from the National Institutes of Health, and grant N00014-15-1-2060 (W.F.B.) from the Office of Naval Research.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2016080930/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Aronson PS: Mechanisms of active H+ secretion in the proximal tubule. Am J Physiol 245: F647–F659, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romero MF, Boron WF: Electrogenic Na+/HCO3- cotransporters: Cloning and physiology. Annu Rev Physiol 61: 699–723, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giebisch G: Two classic papers in acid-base physiology: Contributions of R. F. Pitts, R. S. Alexander, and W. D. Lotspeich. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287: F864–F865, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurtz I: Molecular mechanisms and regulation of urinary acidification. Compr Physiol 4: 1737–1774, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boron WF, Boulpaep EL: Intracellular pH regulation in the renal proximal tubule of the salamander. Basolateral HCO3- transport. J Gen Physiol 81: 53–94, 1983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romero MF, Hediger MA, Boulpaep EL, Boron WF: Expression cloning and characterization of a renal electrogenic Na+/HCO3- cotransporter. Nature 387: 409–413, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parker MD, Boron WF: The divergence, actions, roles, and relatives of sodium-coupled bicarbonate transporters. Physiol Rev 93: 803–959, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang T, Hropot M, Aronson PS, Giebisch G: Role of NHE isoforms in mediating bicarbonate reabsorption along the nephron. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F1117–F1122, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bailey MA: Inhibition of bicarbonate reabsorption in the rat proximal tubule by activation of luminal P2Y1 receptors. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287: F789–F796, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang T, Yang CL, Abbiati T, Schultheis PJ, Shull GE, Giebisch G, Aronson PS: Mechanism of proximal tubule bicarbonate absorption in NHE3 null mice. Am J Physiol 277: F298–F302, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schultheis PJ, Clarke LL, Meneton P, Miller ML, Soleimani M, Gawenis LR, Riddle TM, Duffy JJ, Doetschman T, Wang T, Giebisch G, Aronson PS, Lorenz JN, Shull GE: Renal and intestinal absorptive defects in mice lacking the NHE3 Na+/H+ exchanger. Nat Genet 19: 282–285, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li HC, Du Z, Barone S, Rubera I, McDonough AA, Tauc M, Zahedi K, Wang T, Soleimani M: Proximal tubule specific knockout of the Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3: Effects on bicarbonate absorption and ammonium excretion. J Mol Med (Berl) 91: 951–963, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romero MF, Chen AP, Parker MD, Boron WF: The SLC4 family of bicarbonate (HCO3−) transporters. Mol Aspects Med 34: 159–182, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Y, Wang DK, Jiang DZ, Qin X, Xie ZD, Wang QK, Liu M, Chen LM: Cloning and functional characterization of novel variants and tissue-specific expression of alternative amino and carboxyl termini of products of slc4a10. PLoS One 8: e55974, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang DK, Liu Y, Myers EJ, Guo YM, Xie ZD, Jiang DZ, Li JM, Yang J, Liu M, Parker MD, Chen LM: Effects of Nt-truncation and coexpression of isolated Nt domains on the membrane trafficking of electroneutral Na+/HCO3- cotransporters. Sci Rep 5: 12241, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen LM, Kelly ML, Rojas JD, Parker MD, Gill HS, Davis BA, Boron WF: Use of a new polyclonal antibody to study the distribution and glycosylation of the sodium-coupled bicarbonate transporter NCBE in rodent brain. Neuroscience 151: 374–385, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wetzel RK, Sweadner KJ: Immunocytochemical localization of Na-K-ATPase alpha- and gamma-subunits in rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F531–F545, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amemiya M, Loffing J, Lötscher M, Kaissling B, Alpern RJ, Moe OW: Expression of NHE-3 in the apical membrane of rat renal proximal tubule and thick ascending limb. Kidney Int 48: 1206–1215, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kortenoeven ML, Fenton RA: Renal aquaporins and water balance disorders. Biochim Biophys Acta 1840: 1533–1549, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Felsenfeld DP, Sweadner KJ: Fine specificity mapping and topography of an isozyme-specific epitope of the Na,K-ATPase catalytic subunit. J Biol Chem 263: 10932–10942, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amlal H, Chen Q, Greeley T, Pavelic L, Soleimani M: Coordinated down-regulation of NBC-1 and NHE-3 in sodium and bicarbonate loading. Kidney Int 60: 1824–1836, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu MS, Biemesderfer D, Giebisch G, Aronson PS: Role of NHE3 in mediating renal brush border Na+-H+ exchange. Adaptation to metabolic acidosis. J Biol Chem 271: 32749–32752, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwon TH, Fulton C, Wang W, Kurtz I, Frøkiaer J, Aalkjaer C, Nielsen S: Chronic metabolic acidosis upregulates rat kidney Na-HCO cotransporters NBCn1 and NBC3 but not NBC1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 282: F341–F351, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Praetorius J, Kim YH, Bouzinova EV, Frische S, Rojek A, Aalkjaer C, Nielsen S: NBCn1 is a basolateral Na+-HCO3- cotransporter in rat kidney inner medullary collecting ducts. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286: F903–F912, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ambühl PM, Amemiya M, Danczkay M, Lötscher M, Kaissling B, Moe OW, Preisig PA, Alpern RJ: Chronic metabolic acidosis increases NHE3 protein abundance in rat kidney. Am J Physiol 271: F917–F925, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eladari D, Leviel F, Pezy F, Paillard M, Chambrey R: Rat proximal NHE3 adapts to chronic acid-base disorders but not to chronic changes in dietary NaCl intake. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 282: F835–F843, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee Hamm L, Hering-Smith KS, Nakhoul NL: Acid-base and potassium homeostasis. Semin Nephrol 33: 257–264, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hamm LL, Nakhoul N, Hering-Smith KS: Acid-Base Homeostasis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 2232–2242, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elkjaer ML, Kwon TH, Wang W, Nielsen J, Knepper MA, Frøkiaer J, Nielsen S: Altered expression of renal NHE3, TSC, BSC-1, and ENaC subunits in potassium-depleted rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283: F1376–F1388, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim YH, Kwon TH, Christensen BM, Nielsen J, Wall SM, Madsen KM, Frøkiaer J, Nielsen S: Altered expression of renal acid-base transporters in rats with lithium-induced NDI. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 285: F1244–F1257, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green R, White SJ: The effect of inhibitors of anion exchange and chloride conductance on fluid reabsorption from rat renal proximal convoluted tubule. J Physiol 361: 58P, 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 32.White SJ, Greenwood SL, Green R: The effect of DIDS on fluid reabsorption from the proximal convoluted tubule of the rat: Dependence on the presence of bicarbonate. Q J Exp Physiol 73: 951–958, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sasaki S, Shigai T, Takeuchi J: Intracellular pH in the isolated perfused rabbit proximal straight tubule. Am J Physiol 249: F417–F423, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Occhipinti R, Musa-Aziz R, Boron WF: Evidence from mathematical modeling that carbonic anhydrase II and IV enhance CO2 fluxes across Xenopus oocyte plasma membranes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 307: C841–C858, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Somersalo E, Occhipinti R, Boron WF, Calvetti D: A reaction-diffusion model of CO2 influx into an oocyte. J Theor Biol 309: 185–203, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kinsella JL, Aronson PS: Interaction of NH4+ and Li+ with the renal microvillus membrane Na+-H+ exchanger. Am J Physiol 241: C220–C226, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu Y, Xu K, Chen LM, Sun X, Parker MD, Kelly ML, LaManna JC, Boron WF: Distribution of NBCn2 (SLC4A10) splice variants in mouse brain. Neuroscience 169: 951–964, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ambühl PM, Zajicek HK, Wang H, Puttaparthi K, Levi M: Regulation of renal phosphate transport by acute and chronic metabolic acidosis in the rat. Kidney Int 53: 1288–1298, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Booth AG, Kenny AJ: A rapid method for the preparation of microvilli from rabbit kidney. Biochem J 142: 575–581, 1974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nielsen S, Frøkiaer J, Marples D, Kwon TH, Agre P, Knepper MA: Aquaporins in the kidney: From molecules to medicine. Physiol Rev 82: 205–244, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.